Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

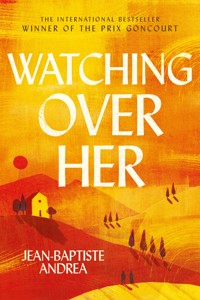

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The international bestseller that has captivated Europe __________________________________ 'Enjoyable and gripping' GUARDIAN 'One of the best historical novels you are likely to read' Christine Dwyer Hickey 'A sprawling fresco and star-crossed love story' NEW YORK TIMES 'An inventive epic' ELLE 'Timeless' DAILY MAIL __________________________________ In an Italian monastery, an infamous sculptor lays on his death bed. During Mimo's final hours, he reveals his life story: his impoverished childhood, his unlikely rise to fame and most importantly, his meeting with Viola, the daughter of a powerful aristocratic family. Mimo and Viola are instantly drawn to one another. Together, they traverse the unrest of the twentieth century. While Mimo becomes a celebrated artist, Viola fights to claim her education and independence. Over the decades, they will lose and find each other, but never will they give up on the love they share. _________________________ Readers around the world love Watching Over Her 'One of the most beautiful, best-written books I have ever read' 'Something truly special' 'Reading this book is pure joy' 'An authentic masterpiece' 'It is a long time since I have been so impressed by a novel'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 608

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © L’Iconoclaste, Paris, 2023

Translation © Frank Wynne 2025

The moral right of Jean-Baptiste Andrea to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Frank Wynne to be identified as the translator has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 80546 273 6

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 274 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is supported by the Institut français

(Royaume-Uni) as part of the Burgess programme.

Product safety EU representative: Authorised Rep Compliance Ltd., Ground Floor,71 Lower Baggot Street, Dublin, D02 P593, Ireland. www.arccompliance.com

To Berenice

There are thirty-two of them. On this autumn day in 1986, thirty-two are still living in this monastery at the end of a rutted track that would make any traveller blench. Nothing has changed in the past thousand years. Not the steepness of the path nor the vertiginous drop. Thirty-two stout hearts – it takes courage to live on the edge of an abyss – thirty-two bodies that were strong in their youth. Some hours from now, they will be thirty-one.

The monks are gathered in a circle around the dying man. There have been many such circles, many farewells, since the walls of the Sacra were first built. There have been moments of grace, moments of doubt, moments when bodies steeled themselves against the looming darkness. There have been and will be other departures, so they wait patiently.

This dying man is unlike the others. He alone has never taken the vows. Yet he has been allowed to stay here for forty years. Each time the subject has been mentioned, each time the question has been raised, a man in purple robes has come – never the same man twice – and it is he who decides. He stays. The dying man is as much a part of the monastery as the cloisters, the columns, the Romanesque capitals, whose conservation owes much to his talent. So let us not complain; he has paid for his sojourn here in kind.

From beneath the wool blanket, only his hands emerge. They are balled into fists either side of his head: an eighty-two-year-old child in the throes of a nightmare. His skin is sallow, like parchment stretched so sharply over jutting bones that it might break. His forehead gleams, made waxen by his fever. It was inevitable that one day his strength would fail. A shame that he never answered their questions. But a man is entitled to his secrets.

Besides, they feel as if they know. Not everything, but the most important facts. Sometimes their opinions differ. To stave off boredom, the monks find they are as gossipy as fishwives. He is alternately a criminal, a defrocked priest, a political refugee. Some say he is being held against his will – a theory that holds little water since they have seen him leave and come back of his own volition; others claim he is there for his own safety. Then there is the most popular theory, and the most clandestine, since in a monastery, romance must be smuggled in: he is there to watch over her. She who waits, in her marble shroud, a few hundred metres from his spartan cell. She who has been waiting now for forty years. All the monks in the Sacra have seen her once. All would like to see her again. They need only ask permission from the abbot, Padre Vincenzo, but few dare to do so – out of fear, perhaps, of the impure thoughts that are said to come to those who come too close to her. And monks have more than enough impure thoughts without finding themselves pursued, in the inky darkness, by dreams with the face of an angel.

The dying man struggles, opens his eyes then closes them again. One of the monks swears he sees a flicker of joy – he is mistaken. Someone gently dabs a cool flannel over his brow, his lips.

The dying man is still struggling, and for once, all the brothers agree.

He is trying to say something.

Of course I’m trying to say something. I’ve witnessed man’s first flight, and I’ve seen him fly faster and faster, further and further. I’ve seen two world wars, the crumbling of nations, I’ve picked oranges on Sunset Boulevard – surely you know I have stories to tell? I apologise. I’m being ungrateful. Since I first decided to hide out here, you have clothed and fed me when you yourselves had nothing, or so little. But I have been silent for too long. Close the shutters – the light hurts my eyes.

He’s getting restless. Close the shutters, brother, the light seems to be troubling him.

The shadows that watch over me in the harsh light of the Piedmont sun, the voices that grow muffled as the long sleep looms. It’s all happened so quickly. Only a week ago you could still see me out in the vegetable garden or up on a ladder – there was always something that needed repair. Age has slowed me, but since no one gave me long to live when I was born, it is quite impressive. Then one morning, I just couldn’t get up. I could see in their eyes that my turn had come, that soon the bell would toll and that I would be carried out to the little garden that faces the mountain, where a sea of poppies grows over centuries of abbots, illuminators, cantors and sacristans.

He’s in a very bad way.

The shutters creak. In the forty years I’ve lived here, they’ve always creaked. Darkness, at last. The darkness of the cinema – which I witnessed being born. At first, nothing but a barren horizon, at first nothing. A dazzling plateau that, as I stare, is filled with shadows by my memory, with forms that resolve to become cities, forests, men and beasts. My actors move towards the front of the stage. Some, I recognise; they haven’t changed. The sublime and the ridiculous, inseparable, smelted together in the same crucible. The currency of tragedy is a rare alloy of gold and glitz.

It’s only a matter of hours.

A matter of hours? Don’t make me laugh. I died long ago.

Another cold compress. He seems to be a little calmer.

But where is it written that the dead cannot tell their stories?

Il Francese. The Frenchman. I have always loathed the moniker, although I have been called much worse. All my joys, all my pains are rooted in Italy. I hail from a country where beauty is ever imperilled. If she should slumber five short minutes, ugliness would ruthlessly devour her. Here, genius grows like a weed. People sing as easily as slaughter, paint as willingly as they play false, let dogs piss against church walls. Not for nothing was a scale of devastation named for an Italian, Mercalli, a scale that quantifies the devastation of an earthquake. One hand tears down, the other builds up, and the emotion is the same.

Italy, kingdom of marble and of manure. My country.

Yet, the fact remains that I was born in France in 1904. Fifteen years earlier, my parents, scarcely married, had left Liguria to seek their fortune. By way of fortune, they found themselves dismissed as wops, were spat upon, were mocked for the way they rolled their Rs – though, to my knowledge the word roll begins with R. My father barely escaped the massacre of Aigues-Mortes in 1893, which took the lives of two close friends: brave Luciano and old Salvatore. They were never again mentioned without these qualifiers.

Families forbade their children from speaking their mother tongue, to avoid the charge of ‘being wops’. They scrubbed them with Marseille soap in the hope of bleaching their bronzed skin a little. But not the Vitaliani. We spoke Italian, we ate Italian. We thought Italian, which is to say larded with superlatives, frequent invocations of Death, copious tears and hands that were rarely still. We cursed as one might pass the salt. Our family was a circus, and we were proud of it.

In 1914, the French government, which had showed scant enthusiasm for protecting Luciano, Salvatore and the others, declared that my father, without a shadow of a doubt, was a good French citizen, worthy of being conscripted. Especially since some bureaucrat, in error or in jest, had shaved ten years from his age while copying his birth certificate. With no smile, no spring in his step, he went to war. His own father had lost his life during the Expedition of the Thousand in 1860. Nonno Carlo had fought in Sicily with Garibaldi. It was no Bourbon bullet that killed him, but a prostitute of doubtful hygiene in the port of Marsala, a detail that the family passed over in silence. Whatever the cause, he was just as dead and the message was clear: war kills.

It killed my father. One day, a gendarme appeared at the workshop above which we lived in La Maurienne. My mother still opened the workshop every day in the hope that it might be some commission which her husband could fulfil on his return, since sooner or later he would have to return to stone carving, restoring gargoyles, making fountains. The gendarme adopted an appropriate countenance, which turned ever more doleful when he saw me, cleared his throat and explained that there had been shell fire, and, well, that was that. When my mother, with great dignity, asked him when the body would be repatriated, he mumbled, explained that there had been horses on the battlefield, other soldiers, that a shell could cause great damage, and so, it was impossible to tell who was who, nor even what was man and what was horse. My mother, thinking he was about to cry, offered him a glass of Amaro Braulio – I have never seen a Frenchman drink it without a grimace – and did not weep herself until many hours later.

Of course, I do not remember all this, or only badly. I know the facts and titivate them with a little colour, those same colours that now slip through my fingers in the tiny cell on Mount Pirchiriano that I have occupied these past forty years. Even today, my French is very poor – or was, some days ago, when I still had the power of speech. No one has called me Il Francese since 1946.

Some days after the visit of the gendarme, my mother explained that, in France, she could not give me the education I required. Already her belly had begun to swell with a brother or a sister – that was never born, or at least not alive – and she covered me in kisses as she explained that she was sending me back to the old country because she believed in me, because she could sense my love of stone despite my tender age, because she knew that I was destined for great things, that it was for this that she had given me my name.

Of the twin burdens of my life, my Christian name was the easier to bear. Yet I passionately despised it.

My mother would often go down to the atelier to watch her husband work. She realised that she was pregnant when she felt me quiver to the sound of the chisel. Till then she had spared no effort, had helped my father shift vast blocks of stone, which perhaps explains what follows.

‘He shall be a sculptor,’ she said.

My father grumbled, told her that it was a dirty trade, the hands, the back, the eyes wore out more quickly than the stone, and that unless a man were Michelangelo, he should spare himself the grief.

My mother nodded, and decided that she would give me a head start.

My name is Michelangelo Vitaliani.

Irediscovered my country in October 1916, accompanied by a drunkard and a butterfly. The drunkard had known my father and initially managed to avoid being conscripted because of the state of his liver, but given the turn events were taking, his cirrhosis might not protect him for much longer. They were conscripting children, old men and cripples. The newspapers claimed that we were winning, that the Hun would soon be history. In our community, news that Italy had joined the Allies the previous year was welcomed as a promise of victory. Those coming home from the front sang a different tune from those who still felt the urge to sing. Ingegnere Carmone, who like the other Eyeties had collected salt from the salt marshes of Aigues-Mortes before opening a grocery shop in Savoie, where he drank much of his stock of wine, had decided to go home. If he was going to die, better to do so in his own house, his lips red from a bottle of Montepulciano to allay his fears.

His country was the Abruzzo. He was a kindly man and agreed to drop me off at Zio Alberto’s on his way. He did so because he felt a little sorry for me and also, I think, for my mother’s eyes. Mothers’ eyes are often something, but my mother’s were a curious almost violet blue. They triggered more than a few fistfights, until my father stepped in to put an end to things. A stonecutter’s hands can be dangerous, even I won’t deny that. The competition quickly lost out.

On the platform of La Praz station, my mother shed great violet tears. My uncle Alberto, who was also a sculptor, would look after me. She swore that she would come and join me as soon as she had sold the stonemason’s studio and earned a little money. A matter of a few weeks, a few months at the most – it took her twenty years. The train blew, belching out black smoke I can still taste to this day, and carried the drunken ingegnere and her only son away.

Grief does not last long when you’re twelve, whatever people say. I didn’t know where the train was headed, but I knew I had never been on a train – or if I had, I didn’t remember. My excitement soon gave way to anxiety. Everything was moving too fast. The moment I tried to focus on some detail – a fir tree, a house – it had disappeared. Landscapes are not meant to move. I felt queasy, but the ingegnere was snoring with his mouth open.

Fortunately, there was the butterfly. It fluttered into the carriage at Saint-Michel-de-Maurienne and landed on the window, between the mountains and me. After a brief struggle with the glass, it surrendered and never moved again. It was not a beautiful butterfly, one of those splendours of colour and gold that I would see later that spring. Just an ordinary butterfly, grey, with a bluish tinge if you looked hard enough, a moth stupefied by daylight. For a moment, I considered pulling its wings off, like any boy my age, but then I realised that by staring at this, the one still element in a whirling world, I no longer felt nauseous. The butterfly stayed there for hours, sent by a friendly power to reassure me, and this was my first inkling that nothing is really as it seems, that a butterfly is not merely a butterfly but a story, something vast lurking within a tiny space, an intuition that would be confirmed some decades later by the first atomic bomb and, perhaps even more so, by what I will leave behind when I die in an underground vault within the crypt of the most beautiful abbey in the country.

When Ingegnere Carmone woke up, he told me all about his project, because he had a project. He was a communist. Do you know what that is? It was an insult I had heard a few times in the village in France – people always wondered whether so-and-so was it. I said, ‘Ha, of course I know. It’s a man who loves men.’

The ingegnere laughed. ‘Yes, in a way, a communist is a man who loves men. Besides, there is no wrong way to love men, you understand that?’ I had never seen him so grave.

The Carmones owned a vast estate in L’Aquila, a province twice blighted by geography. Firstly, it was the only province in Abruzzo with no access to the sea. Secondly, it was ravaged by earthquakes at regular intervals, like the Liguria of my ancestors, except that even that bitch Liguria had access to the sea.

The estate afforded beautiful views over Lake Scanno. The ingegnere planned to build a tower on a gigantic ball bearing to house all the local proletariat, for a modest rent that would allow him to live decently – especially since, being a good communist, he planned to keep the top floor for himself. Two teams of horses would alternate every twelve hours so that the building revolved throughout the day. In this way, every resident, without exception, could enjoy a view of the lake once a day, with no profiteers and no exploited workers. Electricity might one day replace the horses, although Carmone admitted that the project would never get that far. But he liked to dream.

The ball bearing also offered the advantage of separating the building from the ground in the event of an earthquake. Even after a tremor of Force XII on the Mercalli scale – he taught me the name – his tower would have a thirty per cent greater chance of withstanding the shock than an ordinary building. ‘Thirty per cent doesn’t sound like much, but then Force XII is no laughing matter,’ he explained, rolling his eyes. ‘It’s colossal.’

I let myself drift off, my eyes riveted on my butterfly, and we rolled into Italy as the ingegnere tenderly spoke to me about devastation.

Italy and I embraced like old friends meeting for the first time. In my hurry to get off the train at Turin, I tripped over the footboard and ended up spreadeagled on the platform. I lay there for a moment – it never occurred to me to cry – in the rapturous bliss of a priest at his ordination. Italy smelled of cordite. Italy smelled of war.

The ingegnere decided to hire a hackney carriage. It was more expensive than walking, but my mother had given him some money in an envelope and, as he put it, just as the wine must be drunk, money must be spent. Speaking of which, we’ll just go buy ourselves a little carafe of red from the river Po before we set off, if you don’t mind.

I didn’t mind. I was astounded by what I was discovering: soldiers on furlough, soldiers heading back to war, porters, train drivers and a whole host of sleazy people whose professions or aspirations seemed mysterious to the boy I was then. I’d never seen any sleazy people before. I felt as though they were kindly returning my insistent stare, as if to say you’re one of us. Maybe they were just staring at the blue protuberance growing in the middle of my forehead. I made my way through a forest of legs, utterly transfixed by other smells: creosote and leather, metal and rifle barrels, the smell of darkness and of battlefields. And then there was the noise, the deafening roar of a foundry. It shrieked and squeaked and clattered, a form of musique concrète played by illiterates, a far cry from the concert halls where one day jaded celebrities would flock to pretend to enjoy the real thing.

Though I did not realise it, I had arrived right in the midst of futurism. The world was speed, the speed of footsteps, trains, bullets, changes of fortune or changes of alliance. And yet all these men, this great throng, seemed to be holding back. Bodies exulted as they raced towards the train carriages, the trenches, the barbed wire that ringed the horizon. And yet, between two movements, two surges, something seemed to scream I want to live a little longer.

Later, after my career took off, one collector proudly showed me his latest acquisition, La Rivolta by the Futurist painter Luigi Russolo. That would have been in Rome, on the cusp of the 1930s, I think. The collector considered himself a well-informed amateur who was passionate about abstract art. He was a moron. Someone who was not there that day, at Torino Porta Nuova station, cannot possibly understand this painting. They do not realise that it is not abstract. It is a figurative painting. Russolo painted what was blowing up in our faces.

Needless to say, no twelve-year-old would put it in those terms. At the time, I just looked around, wide-eyed, while the ingegnere quenched his thirst at a cheap taverna at the end of the platform. But I saw everything. Proof, if it were needed, that I was not quite like other people.

When we left the station it was snowing lightly. Hardly had we left when a carabiniere stopped us and asked to see my papers. Not my companion’s, just mine. His fingers numb from the cold and the little carafe of red from the Po, Ingegnere Carmone gave him my permit. The carabiniere eyed me with a suspicion that he donned every morning with his uniform and took off every night – unless, of course, it was innate.

‘So, you’re a piccolo francese?’

I did not like being called ‘French’. I liked being called ‘little’ even less.

‘Piccolo francese yourself, cazzino.’

The carabiniere almost choked. Cazzino was the favourite insult of the backyards where I had grown up, and a carabinieri does not choose a profession where he gets to wear an elegant uniform only to be insulted about the size of his manhood.

Being the talented engineer he was, the ingegnere took my mother’s envelope from his pocket and greased the administrative cogs that had seized up. Soon we were on our way. I refused to get into a hackney carriage and pointed to a tram. Carmone grumbled, looked at a map, asked some questions and discovered that the tram would set us down not far from where we wanted to go.

Sitting on the little wooden bench, I travelled through the first big city I had ever seen. I was happy. I had lost my father, I had no idea when I would see my mother again, but I was happy and intoxicated by everything that lay ahead, this block of future I had to climb, to carve out for myself.

‘Tell me something, Signor Carmone?’

‘What’s that?’

‘What is electricity?’

He stared at me, stupefied, then seemed to remember that I had spent the first decade of my life in a little village in Savoie that I had never left.

‘It’s that right there, figlio mio.’ He pointed to a street lamp topped by a magnificent gold globe.

‘So, it’s like a candle, then?’

‘But one that never burns out. Electrons are flowing between two pieces of carbon.’

‘What is an electron? Some kind of fairy?’

‘No, it’s science.’

‘What is science?’

Snowflakes whirled around us, light as a lady’s gown. The ingegnere answered my questions without a whit of impatience or ever being condescending. Soon, we passed a vast building still under construction: the Lingotto where, a few years later, Fiat cars would go up onto the roof via a spiral ramp to the test track where they would make their first circuits after being assembled – an industrial Sacra di San Michele.

The houses became sparser, roads gave way to tracks, the tramway pulled to a halt in what looked like a field. We had to walk the last three kilometres. I’m grateful to this guy, Carmone, for going so far with me, despite the cold, despite the era. We ploughed through the mud, and it seemed to me that already my mother’s eyes were beginning to fade in my memory, to look less violet. But Carmone led me all the way to Zio Alberto’s door.

We had to sorely abuse the bell and pound on the door before Alberto deigned to open it, wearing a dirty vest. He had the same misty eyes as the ingegnere, criss-crossed with a lattice of thin red veins: the two men shared an immoderate love of the grape. My mother had written to let him know of my arrival, so there was not much to explain.

‘This is your new apprentice, Michelangelo, the son of Antonella Vitaliani. Your nephew.’

‘I don’t like being called Michelangelo.’

Zio Alberto looked down at me. I thought he was going to ask me what I liked to be called, to which I would have said ‘Mimo’ – the nickname by which my parents always called me, the name I’d be known by for the next seventy years.

‘I want nothing to do with him,’ said Alberto.

Again, I’ve forgotten a detail. And this is a small but important detail.

‘I don’t understand. I thought Antonell— that Signora Vitaliani had written to you, that it was all agreed.’

‘Oh, she wrote to me. But I don’t want an apprentice like that.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because nobody told me he was a dwarf.’

‘C’è un piccolo problema,’ said old Rosa, the neighbour who attended my mother’s labour one stormy night. The stove clanked and clattered; a strong headwind fanned the flames and painted the walls with a deep red glow. A few of the local matrons, who had come to witness the event and were curious to catch a glimpse of the firm flesh that made their husbands fantasise, had long since fled, making the sign of the cross and whispering il diavolo. An impassive old Rosa carried on humming, sponging and encouraging my mother. The cholera, the cold, plain bad luck and a knife that would never have been drawn but for too much drink had taken her children, her friends and her husbands. She was old, she was ugly, and she had nothing left to lose. So the devil gave her a wide berth; he knew trouble when he saw it. He went for easier prey.

‘C’è un piccolo problema,’ she said, pulling me away from the belly of Antonella Vitaliani. Everything hinged on the word piccolo: it was clear to everyone who saw me that I would remain more or less piccolo all my life. Rosa laid me on my exhausted mother’s breast. My father took the stairs four at a time. Rosa would later say that when he first saw me, he frowned and glanced around as though looking around for his real son rather than this rough draft, then shook his head. I see, it’s like that, is it? Much like when he tapped into a hidden crack in the heart of a block of marble and the work of several weeks dissolved into dust. You can’t blame the stone.

And it was to stone that my difference was attributed. My mother had had no respite from hauling blocks of marble into the workshop that were so huge they would have made the local strongmen red in the face. And, the neighbours said, poor little Mimo suffered as a result. Achondroplasia, some would later claim. They would call me a person of small stature, which, to be honest, was no better than Zio Alberto’s ‘dwarf’. People said I should not be defined by my height. If that was true, why talk about my height at all? I’ve never heard of a ‘person of average stature’.

I never resented my parents. If stone made me what I am, if some dark magic was at work, it gave as much as it took. Stone has always spoken to me, all kinds of stones, limestone, metamorphic rock, even gravestones, on which I would soon lie to listen to the stories of the dead.

‘This is not what was agreed,’ muttered the ingegnere, tapping a gloved finger to his lips. ‘It’s very vexing.’

By now, it was snowing hard. Zio Alberto shrugged and tried to slam the door in our faces, but the ingegnere blocked it with his foot. He took my mother’s envelope from the inside pocket of his old fur jacket and handed it to my uncle. It contained almost every centime of the Vitaliani savings. Years of exile, of drudgery, of skin weathered by sun and salt, of new beginnings, years of marble dust beneath their fingernails, and sometimes a trace of tenderness like the one that had seen me born. This is why those grubby, crumpled banknotes were so precious. This is why Zio Alberto opened the door a fraction.

‘This money was intended for the little man. I mean Mimo,’ Carmone corrected, and flushed crimson. ‘If Mimo agrees to give it to you, he would not be your apprentice, but your partner.’

Zio Alberto nodded slowly. ‘Hmm, a partner.’

He was still hesitant. Carmone waited for as long as he could, then sighed and took a leather pouch out of his pack. Everything about the ingegnere celebrated wear and tear – he was a piece of shreds and patches, his aesthetic was the passing time. But the leather of this pouch, fresh and supple, still seemed to quiver with the rage of the bull that had last worn it. Carmone ran his cracked glove over the pouch, then reluctantly opened it and took out a pipe.

‘This is a pipe that I bought at great expense. It was carved from the stump of the heather plant on which the Hero of Two Worlds, the great Garibaldi himself, is said to have sat during his noble and fruitless attempt to bring Rome into our kingdom.’

I had seen dozens of such pipes sold to gullible Frenchmen in Aigues-Mortes. I had no idea how Carmone had come to buy this one, how he had allowed himself to be duped. I felt a little ashamed for him and for Italy in general. He was a naïve but generous man. This gesture cost him dearly, and I know he did it sincerely, to help me – not because he was in a hurry to get home or afraid to burden himself with a twelve-year-old of unusual proportions. Alberto agreed, and the deal was sealed with a shot of hooch, whose bitterness caused the very air to smart inside his hovel. Then Carmone got to his feet, one for the road, and soon his flickering silhouette disappeared into the snow.

He turned one last time, raised a hand in the yellow phosphorescence of a dying world, and smiled at me. The Abruzzo was far away, he was no longer a young man, and these were harsh times. I never visited Lake Scanno, for fear of discovering that there was not, and never had been, a tower there set on a ball bearing.

I owe much to those women who are termed ‘fallen women’; my uncle Alberto was the son of one – a courageous girl who used to lie beneath men at the port of Genoa, without anger or shame. She was the only person of whom my uncle spoke with a respect, a fervour, bordering on veneration. But the saint of the alleyway was far away, and since Alberto could neither read nor write, his mother became more of a myth with each passing day. As for me, I wrote tolerably well, to the delight of my uncle when he realised.

My uncle Alberto was not my uncle. We did not have a single particle of blood in common. I never truly managed to get to the bottom of the story, but apparently his grandfather owed a debt to mine, an unpaid loan whose moral burden was passed down from generation to generation. In his perverse way, Alberto was honest. Having been petitioned by my mother, he agreed to take me in. He had a small workshop on the outskirts of Turin. Being a bachelor with little taste for extravagance, a few commissions here and there were sufficient to support him – or had been until I arrived. The war – a progressive endeavour much praised by many zealots at the time, who did not favour the term ‘zealot’, preferring ‘poet’ or ‘philosopher’ – had popularised materials that were not only less expensive than stone, but also lighter and easier to produce and work with. Steel was Alberto’s sworn enemy, which offended him even in his sleep. He hated steel even more than he did the Austro-Hungarians or the Germans. Excuses could be made for the Crucci, as the Huns were called here. They had much to be angry about – their national cuisine, their ridiculous pointy helmets. Whereas there was no excuse to create things out of steel, and he would have the last laugh when the whole world collapsed. Alberto had not realised that the whole world had already collapsed. And, to its credit, steel played an important role – it made some magnificent cannons.

Although Alberto looked old, he wasn’t. At thirty-five, he lived alone in a room adjoining his studio. His being a bachelor was surprising, especially since, after a shower, washed cleaned of the marble dust and dressed in his only suit, he was quite handsome. He always visited the same brothel in Turin, where he treated the girls with a respect that was legendary. In the southern regions of the city, between the Lingotto and San Salvario, the expression ‘to do it like Alberto’ was popular in the early 1920s, only falling into disuse when Alberto moved away, taking with him his marbles and his slave – that is to say, me. Being his partner, I still laugh about that.

I have often been asked what role Zio played in what came later. If ‘what came later’ refers to my career, then none; if, on the other hand, it refers to my last sculpture, then it undoubtedly contains a few shards of him. No, not shards, fragments – I would not want anyone to think that Alberto had ever glittered. Zio Alberto was a bastard. Not a monster, just a poor bastard, which amounts to the same thing. I remember him with no hatred, but no sadness.

For almost a year, I lived in his shadow. I cooked, I cleaned. I hauled, I delivered. A hundred times I was almost crushed by a tram, knocked down by a horse, beaten up by some guy who mocked my size and I retorted that at least I had no problem with size downstairs in the piano di sotto, ideally in front of his girlfriend. Ingegnere Carmone would have been thrilled that the atmosphere in our neighbourhood was so electric. Every interaction was a potential lightning strike, a rapid discharge of electrons whose result was always unpredictable. We were at war with the Germans, the Austro-Hungarians, our governments, our neighbours; in other words, we were at war with ourselves. One side wanted war, the other craved peace, tempers flared, and the side that craved peace wound up throwing the first punch.

Zio Alberto forbade me from touching his tools. He once caught me correcting a small holy water font commissioned by the neighbouring parish of Beata Vergine delle Grazie. Once or twice a week, Alberto would go on a monumental drinking binge, and the most recent one had left its mark. The font was crude, offensive; a twelve-year-old could have carved something better, and did so while his uncle drank wine. When Alberto woke, he caught me in flagrante, chisel in hand. He gazed at my work in astonishment, then beat me and insulted me in a Genoese dialect I didn’t understand. Afterwards, he promptly went back to sleep. When he opened his eyes to find me crippled and bruised, he pretended not to remember what had happened. He went straight over to look at the font, decided that he was not dissatisfied with his work and magnanimously offered to deliver it himself.

Alberto would regularly dictate a letter to his mother and allowed me to write one to mine at the same time – he generously paid for the stamp. Antonella did not always reply, being constantly on the road, chasing some work that would keep her going for one week, then another. I missed her violet eyes. My father, the man who had guided my first faltering chisel strokes, the man who had taught me the difference between a file, a rasp and a riffler, was fading away.

In 1917, work commissions were scarcer, Alberto’s moods were darker, and his drinking binges more violent. Columns of soldiers could sometimes be seen marching in the twilight, and the newspapers talked of nothing else but war, the war, yet we felt only vague unease, a sense of disassociation from our surroundings, of never being in the right place. Somewhere over there, a foul beast was sullying the horizon. But we led an almost normal life, the life of sluggards and slackers that imparted a little taste of guilt to everything we ate. At least until 22 August, when the bread ran out and there was nothing left to eat. Turin exploded. The name of Lenin appeared on the city walls; barricades were erected. A revolutionary stopped me in the street on the morning of the 24th and told me to be careful because their barricades were electrified, which, more than anything else, told me how much the world was changing. The man referred to me as ‘comrade’ and patted me on the back. I saw women confronting sheepish soldiers at the barricades, clambering over armoured cars, baring their angry, triumphant breasts knowing they would not shoot. At least not yet.

The rising lasted three days. No one could seem to agree on anything, other than the fact that they were sick of war. In the end, the government got everyone to agree using machine-gun fire, and fifty deaths cooled the revolutionary fervour. I hid out in the studio. One evening shortly after calm had returned, and with it a little bread, Zio Alberto came home in a happier mood than usual. He pretended to lash out at me, chuckled when he saw me dive under the table, then ordered me to take up my pen and dictated a letter to his mother. He stank of cheap wine from the corner taverna.

Mammina,

I have safely received the money order you sent me. Thanks to it, I’m going to be able to buy the little workshop I mentioned to you at Christmas. It is in Liguria, so closer to you. There is no more work here in Turin. But in Liguria, there is a castle that is constantly in need of repair, and a church the authorities are very keen on, so at least that means work. I’ve sold my place here, just signed a contract with that rat Lorenzo, and will soon be leaving with that little shit Mimo. I’ll write to you from Pietra d’Alba. Your loving son.

‘And give me a beautiful signature, pezzo di merda,’ concluded Zio Alberto. ‘A signature that proves that I’m a success.’

It’s curious that, when I think about that time, I wasn’t unhappy. I was alone, I had nothing and no one. In northern Europe forests were being razed and tilled, and sown with shrapnel-filled flesh and a few shells that, years later, would blow up in the face of some innocent rambler; a devastation had been invented that would make Mercalli pale, since he had given his poor scale only twelve degrees. But I was not unhappy, as I realised every night when I prayed to a personal pantheon of idols that changed throughout my life and later came to include opera singers and football players. Perhaps because I was young, my days were pleasant. Only now do I know how much the beauty of the day owes to the prescience of night.

The abbot leaves his office and begins to descend the aptly named Staircase of the Dead. In a few moments, he will be in the annexe, at the bedside of the dying man. The brothers have sent word to say the hour is at hand. The abbot will place the bread of life upon the dying man’s tongue.

Padre Vincenzo moves through the church, paying scant heed to its frescoes, passes through the Zodiac gate and comes to the terraces at the summit of Mount Pirchiriano, from which the abbey overlooks Piedmont. Before him are the ruins of a tower. According to legend, once, with the aid of Saint Michael, a beautiful young peasant girl named Alda took flight from here to escape enemy soldiers. Vanitas vanitatis: when she attempted to perform the feat again to impress the villagers, she was dashed onto the ground below. Just as the part of the tower that bears her name was in the fourteenth century, toppled by one of the many earthquakes that shake the region.

Further on, a few stone steps sink into the ground, barred by a chain and a sign that reads ‘No Trespassing’. The abbot straddles this with an agility commendable for his age. This is not the way to the annexe where the dying man awaits. Before joining him, the abbot wants to see her. She who sometimes troubles his sleep, because he fears a break-in, or worse. You never know what could happen, like the time, fifteen years ago, when Fra Bartolomeo surprised someone just outside the last grille protecting her. The man, an American, tried to pass himself off as a visitor who had lost his way. The abbot instantly smelled a lie, a stench he knew all too well: the smell of the confessional. No tourist could wander into the bowels of the Sacra di San Michele by accident. No, the man was there because he had heard the rumour.

The abbot was correct. Five years later, the same man reappeared with an authorisation duly signed by the Vatican. The gate was opened and the list of those who had contemplated her was increased by one. Leonard B. Williams was a professor from Stanford University in California who had devoted his life to the prisoner of the Sacra, attempting to unravel her mystery. He had published a monograph and a few articles about her; then, silence.

His work, though brilliant, languished on forgotten shelves. The Vatican had shrewdly played its cards, opening that gate as though it had nothing to hide. For years, calm returned. But over the past months, monks had been reporting tourists who were not tourists but snoopers. They were instantly recognisable.

The pressure was mounting.

The abbot spends long minutes descending, making his way through the labyrinthine corridors. He has made the journey so often that he could find his way blindfolded. He is accompanied by the tinkle of a bell – the sound of the bunch of keys he carries. Those damn keys. There is one, and sometimes two, for every door in the abbey, as though mystery lurked behind each one. As though the sacred Eucharist, the greatest of all mysteries, were not enough.

He reaches his goal. He can smell the earth, the humidity, the scent of billions of atoms of granite crushed under their own weight, and even a little of the lush surrounding slopes. Finally, he comes to the gate. The old gate has been replaced with a five-point lock. On his first attempt, the remote-control box doesn’t work. Padre Vincenzo struggles with the rubber keypad. It’s always the same, people talk about progress, it’s 1986 – why can’t these idiots make a remote control that works? He regains his composure. Lord, forgive me my impatience.

Eventually, the red light winks out; the alarm is deactivated. The last corridor is monitored by two state-of-theart surveillance cameras, no bigger than shoeboxes. It is impossible for anyone to get in without sounding the alert. And even if an intruder should manage to get in, what could he do? He could hardly steal her. It took ten strong men to carry her down here.

Padre Vincenzo shudders. It is not theft that he fears. He has not forgotten the crazy man Laszlo Toth. Again, he chastises himself: ‘Crazy’ is hardly a charitable term, let us say ‘unbalanced’. The abbey had come close to tragedy. But just now he doesn’t want to think about Laszlo, about the Hungarian’s grim face and gleaming eyes. Tragedy was averted.

We keep her locked away in order to protect her. The irony is not lost on the abbot. She is here, don’t worry, she is in perfect condition, the only problem is that no one is allowed to see her. No one except the abbot, the padre, the monks who ask to see her, the cardinals still alive who had her locked up here forty years ago, and perhaps a few bureaucrats. At most, some thirty people in the whole world. And, of course, her creator, who possesses his own key. He would come and go at will to tend to her, to wash her. Because, yes, she had to be washed.

The abbot opens the last two locks. He always opens the top lock first, a little quirk that betrays a form of nervousness, an idiosyncrasy he would like to cure, and he vows – as he did on his previous visit – that next time he will open the lower lock first. The door opens soundlessly – the locksmith who vaunted the quality of the hinges did not lie.

He doesn’t turn on the light. The original fluorescent strips were replaced with softer lighting at the same time as the gate, which was for the best since the fluorescent lights were damaging her. But the abbot prefers to contemplate her in the darkness. He steps forward, runs his fingertips over her out of habit. She is a little taller than he. Here, in the centre of the circular room, this primitive sanctuary with its Romanesque vaults, she stands, bowed slightly over her plinth, lost in a dream of stone. The only light comes from the corridor; it carves out two faces and the curve of a wrist. Having stared at her until his eyes were strained, the abbot knows every detail of the statue that sleeps in the shadows.

We keep her locked away in order to protect her.

The abbot suspects that those who put her here were trying to protect themselves.

The city of Savona provided Italy with two popes, Sixtus IV and Julius II. The little village of Pietra d’Alba, some thirty kilometres north, almost provided a third. I believe that I was in part responsible for this failure.

If someone had told me, that morning of 10 December 1917, that the history of the papacy might be swayed by the young boy trudging behind Zio Alberto, I would have laughed. We had been travelling almost non-stop for three days. The whole country had been waiting anxiously for news from the front ever since the savage defeat that the Austro-Hungarians inflicted on us at Caporetto. Some said the front lines had stabilised not far from Venice. Others claimed the opposite, that the enemy would land and slit our throats while we were sleeping or – worse – force us to eat cabbage.

Pietra d’Alba appeared, carved out of the sunrise atop a rocky peak. Its position, I would realise an hour later, was an illusion. Pietra was not perched on a crag, but on the edge of a plateau. So close to the edge, in fact, that there was barely space for two men to walk abreast between the village walls and the cliff edge. Beyond this, fifty metres of sheer void, or rather of pure air, redolent with resin and thyme.

You had to walk through the whole village to discover what had made its reputation: the vast undulating plateau that stretched towards Piedmont, a fragment of Tuscany displaced by the whims of geology. Meanwhile, to east and west, Liguria kept vigil, reminding visitors not to get too comfortable. There was the mountain, and slopes blanketed by forests of a dark green almost as black as the animals that roamed within. Pietra d’Alba was beautiful, with its stone of faded pink encrusted with a thousand dawns.

No matter how exhausted or ill-tempered, a visitor immediately remarked upon two noteworthy buildings. The first, a magnificent baroque church, owed its proportions and its red and green marble façade – unusual to find so far inland – to its patron saint. San Pietro delle Lacrime was built at the place where Saint Peter paused on his way to convert the country louts and boors that would become the French. According to legend, on the night he spent here, he dreamed of his threefold denial of Christ and wept. His tears had seeped into the rock and created the wellspring that now fed a lake a little distance away. The church had been built in 1750 right above this spring, which was still visible in the crypt. Donations poured in, since the waters were said to have miraculous properties. But there had been no miracles, unless it was that the waters transformed this plateau into a little piece of Tuscany.

At Alberto’s insistence, the driver dropped us outside the church. My uncle had insisted on coming from Savona by car, as a conquering hero, not like some yokel in a cart. It was a publicity stunt before such things existed, but it fell flat. It seemed as though the village had thrown a wild party the previous day, to judge by the banners still draped over the fountain, serving as a scarf for a lion, and the confetti lifted and whirled by a playful breeze. Alberto asked the driver to sound his horn, but this merely startled a few doves. Furious, he decided to make the rest of the journey on foot. The workshop he had bought was outside the village.

It was as we left Pietra that we saw the second building. Or rather it saw us, because I felt as though, despite the distance, it was appraising us, deeming any visitor unworthy unless he was a prince, a doge, a sultan, a king or even a marchesa. Every time I came back to Pietra d’Alba after a long absence, the Villa Orsini had the same effect on me, forcing me to stop in my tracks at precisely the same spot, between the last village fountain and the point where the road plunged towards the plateau.

The villa stood on the edge of the forest, some two kilometres from the last houses. Behind it, the steep untamed foothills came to rest against its walls in a spume of vivid green. Here was a land of lofty heights and springs, whose paths, it was whispered, shifted even as you walked them. The only people to venture there were lumberjacks, charcoal burners and hunters. It is to them we owe the story of the shifting paths, invented to salvage their pride when they emerged, haggard and dishevelled Little Thumblings, a week after losing their way.

In front of the villa, for as far as the eye could see, stretched an ocean of orange, lemon and melàngolo trees. This was the Orsini gold, shaped and polished by a sea breeze that breathed its unimaginable gentleness from the coast up to these heights. It was impossible not to pause and gaze at this vibrant, pointillist landscape, a firework of tangerine, melon, apricot, mimosa and sulphur flowers that never faded and contrasted with the dark forest behind the villa, an illustration of the family’s civilising mission as emblazoned on its coat of arms. Ab tenebris, ad lumina. ‘Out of darkness, into light.’ The sense of order, the conviction that everything had its place, which was invariably in the ambit of the Orsini family. The family deferred only to the pre-eminence of God, but were happy to manage His affairs in His absence. As a result, the two notable buildings in Pietra d’Alba were irrevocably linked and would remain so to the very end, twin brothers who rarely spoke but held each other in high regard.

I remember wandering along the rows of orange trees that morning, and the curious eyes that followed us. I remember discovering Alberto’s studio, an old farmhouse flanked by a barn, separated by a large expanse of grass with a walnut tree right in the centre. I remember thinking how much my mother would like this place, when I had earned enough money to send for her. Alberto looked around, his fists on his hips, his eyelashes rimmed with hoarfrost. He nodded contentedly.

‘All that’s left now is to find some good stone.’

In 1983, Franco Maria Ricci wanted to devote a few pages of his magazine FMR to an interview with me. Since he was something of a madman, I agreed. It was the only interview I ever gave. Contrary to what I expected, Ricci did not ask me about her. But she was there at the heart of his piece, as unobtrusive as an elephant.

The article was never published. People in high places got wind of the interview. The print run of the magazine was small and all copies were bought directly from the printer before they could be circulated. Issue 14 of FMR in June 1983 came out a week late and a few pages short. It was probably for the best. Franco sent me a copy that had survived pulping. It will be found in the little trunk under my cell window when I depart. The same trunk with which I arrived in Pietra d’Alba seventy years ago.

In the interview, I say this:

My uncle Alberto was never a great sculptor. This is why, for so long, I too was mediocre. Because I turned a deaf ear to the lone voice inside me and believed him when he said there was such a thing as good stone. There is no such thing as good stone. I should know, because I spent years searching – until I realised that I need only bend down and pick up the stone at my feet.

Old Emiliano, the former stonemason, had sold the workshop for a pittance to Alberto, who gleefully rubbed his hands every time he mentioned the deal. He had rubbed his hands in Turin, rubbed them all through the journey, rubbed them when he set eyes on Pietra d’Alba, the workshop and the barn. He did not stop rubbing his hands until the first night we spent there, when he felt someone crawl into his bed and press two icy feet to his.

Alberto had allowed me to move into the barn, which was his way of saying that the studio and adjoining bedroom were his home. This arrangement suited me perfectly: at thirteen, what boy has not dreamed of sleeping in the straw? Hearing the scream shortly after midnight, I came running and found Alberto about to come to blows with what at first I thought was another man.

‘What are you doing here, you little bastard?’

‘I’m Vittorio!’

‘Who?’

‘Vittorio! Paragraph 3 of the contract!’

I can still hear his timorous voice, dancing between two registers, high-low-high. This was precisely how he introduced himself: Vittorio, Paragraph 3 of the contract. To dismiss the proffered nickname would have been criminal.

Paragraph 3 was three years my senior. In this country of squat men, who lived close to the land to be tended, he was remarkable because of his height. It was the only thing he had inherited from his father, a visiting Swedish agronomist. His reasons for visiting the region were never known, but while here, he had knocked up a local village girl and did not hang around when she told him the news.

It took a moment for us to realise that Paragraph 3 had worked with old Emiliano, and had always curled up against his master to sleep. There was a local saying that, in winter, a man offered the choice between a sack of gold and a roaring fire did not always choose the gold. In these parts, warmth was rare, both in men’s homes and in their hearts. As far as Alberto was concerned, two men sleeping together was unthinkable – in fact, he had never heard of such a thing. Paragraph shrugged and said he would sleep in the barn, which only served to further annoy my uncle – who was beginning to regret not carefully reading the contract sent to him by his solicitor. I reminded him, a little maliciously, that he couldn’t read, but he wasn’t offended. The solicitor should have warned him. Indeed, thinking about it, Signor Dordini could have told him in person on the night they spent drinking with the men from the carpenters’ guild. An exchange of letters later confirmed that Paragraph was part of the fixtures and fittings, and the workshop had been sold for a song with the stipulation that the young man continue to be employed for a further ten years – this was Paragraph 3 of the contract.

In all my life, I have rarely met a man with so little talent for working stone as Paragraph. But he proved a great help to us. He was extremely hard-working, earned little and for the most part was content to have a room and board. Alberto discovered a certain fondness for the boy when he realised that he now had a second slave: a version of me who was more muscular, less insolent and, above all, completely talentless.

The following day, a convoy arrived, a ragtag assortment of carts and sweaty horses appearing in the violet dusk. These were Alberto’s tools sent from Turin. The drivers had a drink with my uncle then set off straight away.