5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

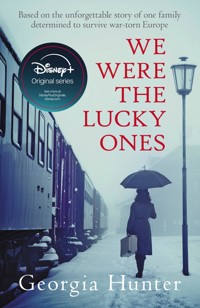

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

NOW A MAJOR DISNEY+ TV SERIES 1939. Three generations of the Kurc family strive to live normal lives despite the growing hardships they face as Jews. But as the realities of war rush to meet them, they are cast to the wind and must do everything they can to find their way through a devastated continent to freedom. Based on an incredible true story that ranges from pre-war Parisian jazz clubs to the desolation of the Siberian gulag, and follows the Kurc family as refugees, prisoners and fighters, We Were the Lucky Ones is a testament to the notion that even in the darkest of times, the human spirit can find a way to survive, and even triumph. 'A truly tremendous accomplishment' Paula McLain

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 689

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

We Were the Lucky Ones

GEORGIA HUNTER

To my grandfather, Addy, with love and wonderment And to my husband, Robert, with all of my heart

Based on true events

By the end of the Holocaust, ninety per cent of Poland’s three million Jews were annihilated; of the more than thirty thousand Jews who lived in Radom, fewer than three hundred survived.

Contents

Part I

CHAPTER ONE

Addy

Paris, France ~ Early March 1939

It wasn’t his plan to stay up all night. His plan was to leave the Grand Duc around midnight and catch a few hours of sleep at the Gare du Nord before his train ride back to Toulouse. Now – he glances at his watch – it’s nearly six in the morning.

Montmartre has this effect on him. The jazz clubs and cabarets, the throngs of Parisians, young and defiant, unwilling to let anything, even the threat of war, dampen their spirits – it’s intoxicating. He finishes his cognac and stands, fighting the temptation to stay for one last set; surely there is a later train he can take. But he thinks of the letter tucked into his coat pocket and his breath catches. He should go. Gathering his overcoat, scarf, and cap, he bids his companions adieu and weaves his way between the club’s dozen or so tables, still half full of patrons smoking Gitanes and swaying to Billie Holiday’s ‘Time on My Hands’.

As the door swings closed behind him, Addy inhales deeply, savouring the fresh air, raw and cool in his lungs. The frost on Rue Pigalle has begun to melt and the cobblestone street shimmers, a kaleidoscope of greys beneath the late-winter sky. He’ll have to walk quickly to make his train, he realises. Turning, he steals a glimpse at his reflection in the club’s window, relieved to find the young man peering back at him presentable, despite the sleepless night. His posture is square, his trousers cinched high on his waist, still sharply cuffed and creased, his dark hair combed back the way he prefers it, neat, without a part. Looping his scarf around his neck, he sets off toward the station.

Elsewhere in the city, Addy presumes, the streets are quiet, deserted. Most iron-gated storefronts won’t open until noon. Some, whose owners have fled to the countryside, won’t open at all – FERMÉ INDÉFINIMENT, the signs in the windows read. But here in Montmartre, Saturday has faded seamlessly to Sunday and the streets are alive with artists and dancers, musicians and students. They stumble from the clubs and cabarets, laughing and carrying on as if they hadn’t a worry in the world. Addy tucks his chin into his coat collar as he walks, looking up just in time to sidestep a young woman in a silver lamé gown, striding in his direction. ‘Excusez-moi, Monsieur,’ she smiles, blushing from beneath a yellow plumed cap. A singer, Addy surmises. A week ago he might have engaged her in conversation. ‘Bonjour, Mademoiselle,’ he nods, continuing on.

A whiff of fried chicken triggers a rumble in his stomach as Addy rounds the corner onto Rue Victor Masse, where a line has already begun to form outside Mitchell’s all-night diner. Through the restaurant’s glass door he can see customers chatting over mugs of steaming coffee, their dishes heaped with American-style breakfasts. Another time, he tells himself, continuing east toward the station.

His train has barely left the terminal when Addy pulls the letter from his coat pocket. Since it arrived yesterday he’s read it half a dozen times and thought of little else. He runs his fingers over the return address. Warszawska 14, Radom, Poland.

He can picture his mother perfectly, perched at her satinwood writing table, pen in hand, the sun catching the soft, plump curve of her jaw. He misses her more than he ever imagined he would when he left Poland six years ago for France. He was nineteen at the time and had thought hard about staying in Radom, where he’d be near his family, and where he hoped he could make a career of his music – he’d been composing since he was a teenager and couldn’t imagine anything more fulfilling than spending his days at a keyboard, writing songs. It was his mother who had urged him to apply to the prestigious Institut Polytechnique in Grenoble – and who had insisted that he attend once he was accepted. ‘Addy, you are a born engineer,’ she said, reminding him of the time when, at seven years old, he’d dismantled the family’s broken radio, strewn its parts across the dining-room table, then put it back together again like new. ‘It’s not so easy to make a living in music,’ she said. ‘I know it’s your passion. You have a gift for it, and you should pursue it. But first, Addy, your degree.’

Addy knew his mother was right. And so, he set off for university, promising that he would return home when he graduated. But as soon as he’d left behind the provincial confines of Radom, a whole new life opened up for him. Four years later, diploma in hand, he was offered a job in Toulouse that paid well. He had friends from all over the world – from Paris, Budapest, London, New Orleans. He had a new taste for art and culture, for paté de foie gras and the buttery perfection of a freshly baked croissant. He had a place of his own (albeit a tiny one) in the heart of Toulouse and the luxury of returning to Poland whenever he pleased, which he did at least twice a year, for Rosh Hashanah and Passover. And he had his weekends in Montmartre, a neighbourhood so steeped in musical talent that it was not uncommon for the locals to share a drink at the Hot Club with Cole Porter, to take in an impromptu performance by Django Reinhardt at Bricktop’s, or, as Addy himself had done, to watch in awe as Josephine Baker fox-trotted across the stage at Zelli’s with her diamond-collared pet cheetah in tow. Addy couldn’t remember a time in his life when he’d been more inspired to put notes to paper – so much so that he’d begun to wonder what it might feel like to move to the United States, the home of the greats, the birthplace of jazz. Maybe in America, he dreamt, he could try his luck at adding his own compositions to the contemporary canon. It was tempting, if it didn’t mean putting an even greater distance between him and his family.

As he slips his mother’s letter from its envelope, a tiny shock runs down Addy’s spine.

Dearest Addy,

Thank you for your letter. Your father and I loved your description of the opera at the Palais Garnier. We’re fine here, although Genek is still furious about his demotion, and I don’t blame him. Halina is the same as ever, so hotheaded I often wonder if she might implode. We are awaiting an announcement from Jakob that he and Bella are engaged, but you know your brother, he can’t be rushed! I’ve been cherishing my afternoons spent with baby Felicia. I can’t wait for you to meet her, Addy. Her hair has begun to grow in – cinnamon red! One of these days she’ll sleep through the night. Poor Mila is exhausted. I keep reminding her it will get easier.

Addy flips the letter over, shifts in his seat. It is here that his mother’s tone darkens.

I should tell you, darling, that some things have changed here in the last month. Rotsztajn has closed his doors to the ironworks – hard to believe, after nearly fifty years in the business. Kosman, too, has moved his family and the watch trade to Palestine, after his store was vandalised one too many times. I’m not relaying this news to worry you, Addy, I just didn’t feel right keeping it from you. Which brings me to the main purpose of this letter: your father and I feel that you should stay in France for Passover and wait until summer to visit us. We’ll miss you terribly, but it seems dangerous to travel right now, especially across German borders. Please, Addy, think about it. Home is home – we’ll be here. In the meantime, send us newswhen you can. How is the new composition coming along?

With love, Mother

Addy sighs, trying once again to make sense of it all. He’s heard of shops closing, of Jewish families leaving for Palestine. His mother’s news doesn’t come as a surprise. It’s her concern that unsettles him. She’s mentioned in the past how things have begun to change around her – she’d been livid when Genek was stripped of his law degree – but mostly Nechuma’s letters are cheerful, upbeat. Just last month, she’d asked if he would join her for a Moniusko performance at the Grand Theatre in Warsaw and had told him of the anniversary dinner she and Sol enjoyed at Wierzbicki’s, of how Wierzbicki himself had greeted them at the door, offered to prepare something special for them, off the menu.

This letter is different. His mother, Addy realises, is afraid.

He shakes his head. Not once in his twenty-five years has he ever known Nechuma to express fear of any kind. Nor has he or any of his brothers and sisters ever missed a Passover together in Radom. Nothing is more important to his mother than her family – and now she is asking him to stay in Toulouse for the holiday. At first, Addy had convinced himself that she was being overly anxious. But was she?

He stares out the window at the familiar French countryside. The sun is visible from behind the clouds; there are hints of spring colour in the fields. The world looks benign, the same as it always has. And yet these cautionary words from his mother have shifted his equilibrium, thrown him off-balance.

Addy closes his eyes, thinking back to his last visit home in September, searching for a clue, something he might have missed. His father, he recalls, had played his weekly game of cards with a group of fellow merchants – Jews and Poles – beneath the white-eagle fresco on the ceiling of Podworski’s Pharmacy; Father Krol, a priest at the Church of Saint Bernardine and an admirer of Mila’s virtuosity at the piano, had stopped by for a recital. For Rosh Hashanah, the cook had made honey-glazed challah, and Addy had stayed up listening to Benny Goodman, drinking Côte de Nuits and laughing with his brothers late into the night. Even Jakob, reserved as he usually was, had set down his camera and joined in the camaraderie. Things had seemed relatively normal.

And then Addy’s throat goes dry as he considers a thought: what if the clues were there but he hadn’t been paying enough attention? Or worse, what if he’d missed them simply because he didn’t want to see them?

His mind flashes to the freshly painted swastika he’d come across on the wall of the Jardin Goudouli in Toulouse. To the day he’d overheard his bosses at the engineering firm whispering about whether they should consider him a liability – they’d thought he was out of earshot. To the shops closed all over Paris. To the photographs in the French papers of the aftermath of November’s Kristallnacht: smashed storefronts, synagogues burnt to the ground, thousands of Jews fleeing Germany, rolling their bedside lamps and potatoes and elderly along with them in wheelbarrows.

The signs were there, for sure. But Addy had downplayed them, brushed them off. He’d told himself that there was no harm in a little graffiti; that if he were to lose his job, he’d find a new one; that the events unfolding in Germany, though disturbing, were happening across the border and would be contained. Now, though, with his mother’s letter in hand, he sees with alarming clarity the warnings he’d chosen to ignore.

Addy opens his eyes, nauseated suddenly by a single notion: you should have returned home months ago.

He folds the letter into its envelope and slides it back into his coat pocket. He’ll write to his mother, he resolves. As soon as he gets to his flat in Toulouse. He’ll tell her not to worry, that he will be returning to Radom as planned, that he wants to be with the family now more than ever. He’ll tell her that the new composition is coming along well, and that he looks forward to playing it for her. This thought brings a trace of comfort, as he imagines himself at the keys of his parents’ Steinway, his family gathered around.

Addy lets his gaze fall once again to the placid countryside. Tomorrow, he decides, he’ll buy a train ticket, line up his travel documents, pack his belongings. He won’t wait for Passover. His boss will be angry with him for leaving sooner than expected, but Addy doesn’t care. All that matters is that in a few short days, he’ll be on his way home.

MARCH 15, 1939: A year after annexing Austria, Germany invades Czechoslovakia. Meeting little resistance, Hitler establishes the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia from Prague the next day. With this occupation, the Reich gains not only territory but also skilled labour and massive firepower in the form of weaponry manufactured in those regions – enough to arm nearly half of the Wehrmacht at the time.

CHAPTER TWO

Genek

Radom, Poland ~ March 18, 1939

Genek lifts his chin and a plume of smoke snakes from a part in his lips toward the grey-tiled ceiling of the bar. ‘Last hand,’ he declares.

Across the table, Rafal catches his eye. ‘So soon?’ He takes a drag from his own cigarette. ‘Did your wife promise you something special if you got home at a decent hour?’ Rafal winks, exhaling. Herta had joined the group for dinner but had left early.

Genek laughs. He and Rafal have been friends since grade school, when much of their time was spent huddled over lunch trays discussing which of their classmates to ask to the year-end studniówka ball, or whom they’d rather see naked, Evelyn Brent or Renée Adorée. Rafal knows Herta isn’t like the girls Genek used to date, but he likes to give him hell when Herta isn’t around. Genek can hardly blame him. Until he met Herta, women were his weakness (cards and cigarettes, too, if he’s being honest). With his blue eyes, a dimple on each cheek, and an irresistible Hollywood charm, he’d spent most of his twenties basking in the role of one of Radom’s most sought-after bachelors. At the time, he hadn’t minded the attention in the least. But then Herta came along and all of that changed. It’s different now. She’s different.

Under the table, something brushes Genek’s calf. He glances at the young woman sitting beside him. ‘Wish you would stay,’ she says, her eyes catching his. Genek had just met the girl that night – Klara. No, Kara. He can’t remember. She is a friend of Rafal’s wife, visiting from Lublin. She curls a corner of her mouth into a coy smile, the toe of her oxford still pressed against his leg.

In his former life he might have stayed. But Genek no longer has any interest in flirting. He smiles at the girl, feeling a little sorry for her. ‘Matter of fact, I think I’m out,’ he says, setting his cards down on the table. He stubs out his Murad, leaving the butt to stick up like a crooked tooth in the crowded ashtray, and stands. ‘Gentlemen, ladies – it’s always a pleasure. I’ll see you. Ivona,’ he adds, addressing Rafal’s wife and nodding toward his friend, ‘it’s on you to keep that one out of trouble.’ Ivona laughs. Rafal winks again. Genek throws up a two-fingered salute and heads for the door.

The March night is unusually cold. He buries his hands in his coat pockets and sets off at a hurried clip toward Zielona Street, relishing the prospect of returning home to the woman he loves. Somehow, he’d known Herta was his girl the instant he laid eyes on her, two years ago. The weekend is still sharp in his memory. They were skiing in Zakopane, a resort town tucked amid the peaks of Poland’s Tatra Mountains. He was twenty-nine, Herta twenty-five. They’d happened to share a chair lift, and on the ten-minute ride to the summit, Genek had fallen for her. For her lips, to start, because they were full and heart-shaped, and about all he could see of her behind the cream-white wool of her hat and scarf. But there was also her German accent, which forced him to listen to her in a way that he wasn’t used to, and her smile, so uninhibited, and the way, halfway up the mountain, she’d tipped her head back, closed her eyes, and said, ‘Don’t you just love the smell of pine in the wintertime?’ He’d laughed, thinking for a moment that she was joking before realising she wasn’t; her sincerity was a trait he would grow to admire, along with her unabashed love of the outdoors and her propensity for finding beauty in the simplest of things. He’d followed her down the slope, trying not to think too much of the fact that she was twice the skier he would ever be, then slid up next to her in the lift line and asked her to dinner. When she hesitated, he smiled and told her that he’d already booked a horse-drawn sleigh. She laughed and, to Genek’s delight, agreed to the date. Six months later, he proposed.

Inside his apartment, Genek is glad to see a glow emanating from beneath the bedroom door. He finds Herta in bed with a favourite collection of Rilke poems propped on her knees. Herta is originally from Bielsko, a largely German-speaking town in western Poland. In conversation, she rarely uses the language she grew up with any more, but she enjoys reading in her native tongue, poetry especially. She doesn’t appear to notice as Genek enters the room.

‘That must be one engaging verse,’ Genek teases.

‘Oh!’ Herta says, looking up. ‘I didn’t hear you come in.’

‘I was worried you’d be asleep,’ Genek grins. He slips out of his coat, and tosses it over the back of a chair, blowing into his hands to warm them.

Herta smiles and sets her book down on her chest, using a finger to keep her place. ‘You’re home far earlier than I thought you’d be. Have you lost all of our money at the table? Did they kick you out?’

Genek removes his shoes and his blazer, unbuttons his shirt cuffs. ‘I’m ahead, actually. It was a good night. Just a bore without you.’ Against the white sheets, in her pale yellow gown with her deep-set eyes and perfect lips and chestnut hair spilling in waves over her shoulders, Herta looks like something out of a dream, and once again Genek is reminded how immensely lucky he is to have found her. He undresses down to his underwear and crawls into bed beside her. ‘I missed you,’ he says, propping himself on an elbow and kissing her.

Herta licks her lips. ‘Your last drink, let me guess – Bichat.’

Genek nods, laughs. He kisses her again, his tongue finding hers.

‘Love, we should be careful,’ Herta whispers, pulling away.

‘Aren’t we always careful?’

‘It’s just – about that time.’

‘Oh,’ Genek says, savoring her warmth, the sweet floral residue of shampoo in her hair.

‘It would be foolish to let it happen now,’ Herta adds, ‘don’t you think?’

Hours before, over dinner, they’d talked with their friends about the threat of war, about how easily Austria and Czechoslovakia had fallen into the hands of the Reich, and of how things had begun to change in Radom. Genek had ranted about his demotion to assistant at the law firm and had threatened to move to France. ‘At least there,’ he’d fumed, ‘I could use my degree.’

‘I’m not so sure you’d be better off in France,’ Ivona had said. ‘The Führer isn’t just targeting German-speaking territories any more. What if this is just the beginning? What if Poland is next?’

The table had quieted for a moment before Rafal broke the silence. ‘Impossible,’ he claimed, with a dismissive shake of his head. ‘He might try, but he’ll be stopped.’

Genek had agreed. ‘The Polish Army would never let it happen,’ he said. Genek recalls now that it was during this conversation that Herta had stood to excuse herself.

His wife is right, of course. They should be careful. To bring a child into a world that has begun to feel disturbingly close to the brink of collapse would be imprudent and irresponsible. But lying so close, Genek can think of nothing but her skin, the curve of her thigh against his. Her words, like the tiny bubbles in his last flute of champagne, float from her mouth, dissolving somewhere in the back of his throat.

Genek kisses her a third time, and as he does Herta closes her eyes. She only half means it, he thinks. He reaches over her for the light, feeling her soften beneath him. The room goes dark, and he slips a hand under her gown.

‘Cold!’ Herta shrieks.

‘Sorry,’ he whispers.

‘No, you’re not. Genek …’

He kisses her cheekbone, her earlobe. ‘The war, the war, the war,’ he says softly. ‘I’m tired of it already and it hasn’t even begun.’ He marches his fingers from her ribs down to her waistline.

Herta sighs, then giggles.

‘Here’s a thought,’ Genek adds, his eyes widening as if he’s just had a revelation. ‘What if there is no war?’ He shakes his head, incredulous. ‘We’ll have deprived ourselves for nothing. And Hitler, the little prick, will have won.’ He flashes a smile.

Herta runs a finger along the hollow of his cheek. ‘These dimples are the death of me,’ she says, shaking her head. Genek grins harder, and Herta nods. ‘You’re right,’ she acquiesces. ‘It would be tragic.’ Her book meets the floor with a thud as she rolls to her side to face him. ‘Bumsen der krieg.’

Genek can’t help but laugh. ‘I agree. Fuck the war,’ he says, pulling the blanket up over their heads.

CHAPTER THREE

Nechuma

Radom, Poland ~ April 4, 1939 – First day of Passover

Nechuma has arranged the table with her finest china and crockery, setting each place just so, atop a white lace tablecloth. Sol sits at the head, his worn, leatherbound Haggadah in one hand, a polished silver kiddush cup in the other. He clears his throat. ‘Today …’ he begins, lifting his gaze to the familiar faces around the table, ‘we honour what matters most – our family, and our tradition.’ His eyes, normally flanked with laugh lines, are serious, his voice a sober baritone. ‘Today,’ he continues, ‘we celebrate the Festival of Matzahs, the time of our liberation.’ He glances down at his text. ‘Amen.’

‘Amen,’ the others echo, sipping their wine. A bottle is passed and glasses are refilled.

The room is quiet as Nechuma stands to light the candles. Making her way to the middle of the table, she strikes a match and cups a palm around it, bringing it quickly to each wick, hoping the others won’t notice the flame shivering between her fingers. When the candles are lit, she circles a hand over them three times and then shields her eyes as she recites the opening blessing. Taking her place at the end of the table opposite her husband, she folds her hands over her lap and her eyes meet Sol’s. She nods, an indication for him to begin.

As Sol’s voice once again fills the room, Nechuma’s gaze slips to the chair she’s left empty for Addy, and her chest grows heavy with a familiar ache. His absence consumes her.

Addy’s letter had arrived a week ago. In it, he’d thanked Nechuma for her candor, and asked her please not to worry. He would return home as soon as he could collect his travel documents, he wrote. This news brought Nechuma both relief and concern. She had no greater wish than to have her son home for Passover, except, of course, to know that he was safe in France. She’d tried to be honest, had hoped he would understand that Radom was a dismal place right now, that travelling through German-occupied regions wasn’t worth the risk, but perhaps she’d held back too much. It wasn’t just the Kosmans, after all, who had fled. There were half a dozen others. She hadn’t told him about the Polish customers they’d recently lost at the shop, or about the bloody brawl that had broken out the week before between two of Radom’s soccer teams, one Polish, the other Jewish, and how young men from each team still walked around with split lips and black eyes, glaring at one other. She’d left it all unsaid to spare him pain and worry, but perhaps in doing so, had she exposed him to a greater danger?

Nechuma had replied to Addy’s letter, imploring him to be safe in his travels, and then assumed he was en route. Every day since, she’s jumped at the sound of footsteps in the foyer, her heart thrumming at the thought of finding Addy at the door, a smile spread across his handsome face, his valise in hand. But the footsteps are never his. Addy has not come.

‘Maybe he had to wrap up some things at the firm,’ Jakob offered earlier in the week, sensing her growing concern. ‘I can’t imagine his boss would let him leave without a couple of weeks’ notice.’

But all Nechuma can think is: what if he’s been held up at the border? Or worse? To reach Radom, Addy would have to travel north through Germany, or south through Austria and Czechoslovakia, both of which have fallen under Nazi rule. The possibility of her son in the hands of the Germans – a fate that might have been avoided had she been more forthright with him, had she been more adamant in asking him to remain in France – has kept her lying awake at night for days.

As tears prick at her eyes, Nechuma’s thoughts cartwheel back in time to another April day, during the Great War, a quarter century ago, when she and Sol were forced to spend Passover huddled in the building’s basement. They’d been evicted from their apartment and, like so many of their friends at the time, had nowhere else to go. She remembers the suffocating stench of human waste, the air thick with incessant moans of empty stomachs, the thunder of distant cannons, the rhythmic scrape of Sol’s blade against wood as he whittled away at a log of old firewood with a paring knife, sculpting figurines for the children to play with and picking splinters from his fingers. The holiday had come and gone without acknowledgement, never mind a traditional Seder. Somehow, they lived three years in that basement, the children surviving on her breast milk while Hungarian officers bivouacked in their apartment upstairs.

Nechuma looks across the table at Sol. Those three years, though they nearly broke her, are now as far behind her as possible, almost as if they’d happened to someone else entirely. Her husband never speaks of that time; her children, thankfully, do not recall the experience in any palpable way. There have been pogroms since – there will always be pogroms – but Nechuma refuses to contemplate a return to a life in hiding, a life without sunlight, without rain, without music and art and philosophical debate, the simple, nourishing riches she’s grown to cherish. No, she will not go back underground like some kind of feral creature; she will not live like that ever again.

It couldn’t possibly come to that.

Her mind turns once more, to her own childhood, to the sound of her mother’s voice telling her how it was common when she herself was growing up in Radom for little Polish boys to hurl stones at her kerchiefed head at the park, how riots had erupted all over the city when the town synagogue was first built. Nechuma’s mother had shrugged it off. ‘We just learnt to keep our heads down, and our children close,’ she said. And sure enough, the attacks, the pogroms, they passed. Life went on, as it did before. As it always does.

Nechuma knows that the German threat, like the threats that came before it, will also pass. And anyway, their situation now is far different than it was during the Great War. She and Sol have worked tirelessly to earn a living, to establish themselves among the city’s top-tier professionals. They speak Polish, even at home, while many of the city’s Jews converse only in Yiddish, and rather than live in the Old Quarter as the majority of Radom’s less affluent Jews do, they own a stately apartment in the centre of town, complete with a cook and a maid and the luxuries of indoor plumbing, a bathtub they imported themselves from Berlin, a refrigerator, and – their most prized possession – a Steinway baby grand piano. Their fabric shop is thriving; Nechuma takes great care on her buying trips to collect the highest-quality textiles, and their clients, both Polish and Jewish, come from as far as Kraków to purchase their ladies’ wear and silk. When their children were of school-age, Sol and Nechuma sent them to elite private academies, where, thanks to their tailored shirts and perfect Polish, they fit in seamlessly with the majority of the students, who were Catholic. In addition to providing them with the best possible education, Sol and Nechuma hoped to give their children a chance to sidestep the undertones of anti-Semitism that had defined Jewish life in Radom since before any of them could remember. Though the family was proudly rooted in its Jewish heritage and very much a part of the local Jewish community, for her children Nechuma chose a path she hoped would steer them toward opportunity – and away from persecution. It is a path she stands by, even when now and then at the synagogue, or while shopping at one of the Jewish bakeries in the Old Quarter, she catches one of Radom’s more orthodox Jews glancing at her with a look of disapproval – as if her decision to mix with the Poles has somehow diminished her faith as a Jew. She refuses to be bothered by these encounters. She knows her faith – and besides, religion, to Nechuma, is a private matter.

Pinching her shoulder blades down her back, she feels the weight of her bosom lift from her ribs. It’s not like her to be so inundated with worry, so distracted. Pull yourself together, she chides. The family will be fine, she reminds herself. They have a healthy savings. They have connections. Addy will turn up. The mail has been unreliable; in all likelihood, a letter explaining his absence will arrive any day. It will all be fine.

As Sol recites the blessing of the karpas, Nechuma dips a sprig of parsley into a bowl of salt water and her hand brushes Jakob’s. She sighs, feeling the tension begin to drain from her jaw. Sweet Jakob. He catches her eye and smiles, and Nechuma’s heart fills with gratitude for the fact that he is still living under her roof. She adores his company, his calm. He’s different from the others. Unlike his siblings, who entered the world red-faced and wailing, Jakob arrived as white as her hospital bedsheets and silent, as if mimicking the giant snowflakes falling peacefully to the earth outside her window on that wintery February morning, twenty-three years ago. Nechuma would never forget the harrowing moments before he finally cried – she was sure at the time that he wouldn’t survive the day – or how, when she held him in her arms and looked into his inky eyes, he’d stared up at her, the skin over his brow creased with a small fold, as if he were deep in thought. It was then that she understood who he was. Quiet, yes, but astute. Like his brothers and sisters born before and after him, a tiny version of the person he would grow up to be.

She watches as Jakob leans to whisper something in Bella’s ear. Bella brings a napkin to her lips, stifling a smile. On her collar, a pin catches the candlelight – a gold rose-shaped brooch with an ivory pearl at its center, a gift from Jakob. He’d given it to her a few months after they met at gymnasium. He was fifteen at the time, she fourteen. Back then, all Nechuma knew of Bella was that she took her studies seriously, that she came from a family of modest means (according to Jakob, her father, a dentist, was still settling the loans he’d taken on to pay for his daughters’ education), and that she sewed many of her own clothes, a revelation that impressed Nechuma and prompted her to wonder which of Bella’s smartest blouses were store-bought and which were handmade. It was shortly after Jakob gave Bella the brooch that he declared her his soulmate.

‘Jakob, love, you’re fifteen … and you’ve just met!’ Nechuma had exclaimed. But Jakob wasn’t one to exaggerate, and here they are, eight years later, inseparable. It’s only a matter of time before they are married, Nechuma figures. Perhaps Jakob will propose when the talk of war has subsided. Or maybe he’s waiting until he’s saved enough to afford his own place. Bella lives with her parents, too – just a few blocks west on Witolda Boulevard. Whatever the case, Nechuma has no doubt that Jakob has a plan.

At the head of the table, Sol breaks a piece of matzah gently in two. He sets one half of the matzah on a plate and wraps the other in a napkin. When the children were younger, Sol would spend weeks plotting the perfect hiding spot for the matzah, and when the time came in the ceremony to unearth the hidden afikomen, the kids would scamper like mice through the apartment in search of it. Whoever was lucky enough to find it would barter ruthlessly until inevitably walking away with a proud smile and enough zloty in his or her palm to purchase a sack of fudge krówki at Pomianowski’s candy store. Sol was a businessman and played hard – the King Negotiator, they called him – but his children knew well that deep down he was as soft as a mound of freshly churned butter, and that with enough patience and charm, they could milk him for every zloty in his pocket. He hasn’t actually hidden the matzah in years, of course; his children, as teenagers, finally boycotted the ritual – ‘We’re a bit old for it, don’t you think, Father?’ they said – but Nechuma knows that the moment his granddaughter Felicia has learnt to walk, he’ll resume the tradition.

It’s Adam’s turn to read aloud. He lifts his Haggadah and peers at it through thick-rimmed eyeglasses. With his narrow nose, high, sharp cheekbones, and flawless skin accentuated in the candlelight, he appears almost regal. Adam Eichenwald had arrived in the Kurc household several months ago, when Nechuma set a room for let sign in the window of the fabric store. Her uncle had recently died, leaving the family with an empty bedroom, and her home, even with her two youngest still there, had begun to feel empty. Nechuma loved nothing more than a crowded dinner table. When Adam had stepped into the shop to enquire, she was delighted; she offered him the room immediately.

‘What a fine-looking young man!’ Sol’s sister Terza had exclaimed, after he left. ‘He’s thirty-two? He looks a decade younger.’

‘He’s Jewish, and he’s smart,’ Nechuma added. What are the odds, the women had whispered about the boy – a graduate in architecture at the Polytechnic National University in Lvov – leaving 14 Warszawska Street unwed? And sure enough, a few weeks later, Adam and Halina were an item.

Halina. Nechuma sighs. Born with an inexplicable mop of honey-blonde hair and incandescent green eyes, Halina is the youngest and the most petite of her children. What she lacks in stature, however, she makes up tenfold in personality. Nechuma has never met a child so obstinate, so capable of talking her way into (or out of) practically anything. She recalls the time when, at fifteen, Halina charmed her mathematics professor out of giving her a demerit when he discovered she’d skipped class to see the matinee of Trouble in Paradise on opening day, and the time when, at sixteen, she convinced Addy to take a last-minute overnight train with her to Prague so they could wake up in the City of a Hundred Spires on the birthday they shared. Adam, bless his heart, is clearly allured by her. Thankfully, he’s proven nothing but respectful in Sol and Nechuma’s presence.

When Adam has finished reading, Sol offers a prayer over the remaining matzah, breaks off a piece, and passes the plate. Nechuma listens as the soft crack of unleavened bread makes its way around the table. ‘Baruch a-tah A-do-nai,’ Sol sings, but stops short when he’s interrupted by a high-pitched cry. Felicia. Blushing, Mila apologises and slips from her seat to scoop the baby from her bassinet in the corner of the room. Tap-dancing her feet, she shushes softly into Felicia’s ear to soothe her. As Sol begins again, Felicia squirms beneath the folds of her swaddle, her face contorting, reddening. When she wails a second time, Mila excuses herself, hurrying down the hallway to Halina’s bedroom. Nechuma follows.

‘What’s wrong, love?’ Mila whispers, rubbing a finger along Felicia’s top gum as she’s seen Nechuma do, trying to pacify her. Felicia turns her head, arches her back, cries harder.

‘Do you think she’s hungry?’ Nechuma asks.

‘I fed her not too long ago. I think she’s just tired.’

‘Here,’ Nechuma says, taking her granddaughter from Mila’s arms. Felicia’s eyes are pinched shut, her hands curled tight into fists. Her bawls come in short, shrill bursts.

Mila sits down heavily at the foot of Halina’s bed. ‘I’m so sorry, Mother,’ she says, straining not to yell over Felicia’s cries. ‘I hate that we’re causing a fuss.’ She rubs her eyes with the heels of her hands. ‘I can barely even hear myself think.’

‘No one minds,’ Nechuma says, holding Felicia close to her chest, rocking her gently. After a few minutes, the cries wane to whimpers and soon she is quiet again, her expression peaceful. It’s mesmerising, the joy of holding a baby in your arms, Nechuma thinks, breathing in Felicia’s sweet almond scent.

‘I’m such a fool for assuming this would be easy,’ Mila says. When she looks up her eyes are bloodshot, the skin beneath them translucent purple, as if the lack of sleep has left a bruise. She’s trying – Nechuma can see that. But it’s tough being a new mother. The transition has left her reeling.

Nechuma shakes her head. ‘Don’t be so hard on yourself, Mila. It’s not what you thought it would be, but that’s to be expected. With children it’s never what you think it’s going to be.’ Mila looks at her hands and Nechuma recalls how, when she was younger, her eldest daughter wanted nothing more than to be a mother – how she would tend to her dolls, cradling them in the crook of her arm, singing to them, even pretending to nurse them; how she took great pride in caring for her younger siblings, offering to tie their shoes, wrap gauze around their bloodied knees, read to them before bed. Now that she has a child of her own, however, Mila seems overwhelmed by it, as if it were the first time she’d held a baby in her arms.

‘I wish I knew what I was doing wrong,’ Mila says.

Nechuma sits down gently beside her at the foot of the bed. ‘You’re doing fine, Mila. I told you, babies are difficult. Especially the first. I nearly lost my mind when Genek was born, trying to figure it out. It just takes some time.’

‘It’s been five months.’

‘Give it a few more.’

Mila is quiet for a moment. ‘Thank you,’ she finally whispers, looking over at Felicia sleeping peacefully in Nechuma’s arms. ‘I feel like a wretched failure.’

‘You’re not. You’re just tired. Why don’t you call for Estia. She’s all done in the kitchen; she can help while we finish our meal.’

‘That’s a good idea.’ Mila sighs, relieved. She leaves Felicia with Nechuma while she goes off to find the maid. When she and Nechuma return to their seats, Mila glances at Selim. ‘Okay?’ he mouths, and she nods.

Sol spoons a mound of horseradish onto a piece of matzah, and the others do the same. Soon, he is singing again. When the blessing of the korekh is complete, it’s time, finally, to eat. Platters are passed, and the dining room is filled with the murmur of conversation and the scrape of silver spoons on china as dishes are piled high with salted herring, roasted chicken, potato kugel, and sweet apple charoset. The family sips wine and talks quietly, gingerly avoiding the subject of war, and wondering aloud of Addy’s whereabouts.

At the sound of Addy’s name, the ache creeps back into Nechuma’s chest, bringing with it an orchestra of worries. He has been arrested. Incarcerated. Deported. He is hurt. Afraid. He hasn’t a way to contact her. She glances again at her son’s empty seat. Where are you, Addy? She bites her lip. Don’t, she admonishes, but it’s too late. She’s been drinking her wine too quickly and has lost her edge. Her throat closes and the table melts into a blurry swath of white. Her tears are poised to flow when she feels a hand over hers, beneath the table. Jakob’s. ‘It’s the horseradish root,’ she whispers, waving her free hand in front of her face, blinking. ‘Gets me every time.’ She dabs discreetly at the corners of her eyes with her napkin. Jakob nods knowingly and wraps his fingers tightly around hers.

Months later, in a different world, Nechuma will look back on this evening, the last Passover when they were nearly all together, and wish with every cell in her body that she could relive it. She will remember the familiar smell of the gefilte, the chink of silver on porcelain, the taste of parsley, briny and bitter on her tongue. She will long for the touch of Felicia’s baby-soft skin, the weight of Jakob’s hand on hers beneath the table, the wine-induced warmth in the pit of her belly that begged her to believe that everything might actually turn out all right in the end. She will remember how happy Halina had looked at the piano after their meal, how they had danced together, how they all spoke of missing Addy, assuring each other that he’d be home soon. She will replay it all, over and over again, every beautiful moment of it, and savour it, like the last perfect klapsa pears of the season.

AUGUST 23, 1939: Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union sign the Molotov–Ribbentrop Nonaggression Pact, a secret agreement outlining specific boundaries for the future division of much of Northern and Eastern Europe between German and Soviet powers.

SEPTEMBER 1, 1939: Germany invades Poland. Two days later, in response, Britain, France, Australia, and New Zealand declare war on Germany. World War II in Europe begins.

CHAPTER FOUR

Bella

Radom, Poland ~ September 7, 1939

Bella sits upright, knees pulled to her chest, a handkerchief balled in her fist. She can just make out the square-cornered silhouette of a leather suitcase by her bedroom door. Jakob is perched on the edge of the bed by her feet, the cold night-time air still clinging to the tweed of his overcoat. She wonders if her parents had heard him climbing the stairs to their second-storey flat, tiptoeing down the hallway to her room. She had given Jakob a key to the flat years ago so he could visit when he pleased, but he’d never been so bold as to come at this hour. She pushes her toes into the space between the mattress and his thigh.

‘They’re sending us to Lvov to fight,’ Jakob says, out of breath. ‘If anything should happen, let’s meet there.’ Bella searches for Jakob’s face in the shadows, but all she can see is the oval of his jawline, the dim whites of his eyes.

‘Lvov,’ she whispers, nodding. Bella’s younger sister Anna and her new husband, Daniel, live in Lvov, a city 350 kilometres south-east of Radom. Anna had been begging Bella to consider moving closer to her, but Bella knew she couldn’t leave Jakob. In the eight years that they’ve known each other, they’ve never lived more than four hundred metres apart.

Jakob reaches for her hands, laces his fingers between hers. He brings them to his mouth and kisses them. The gesture reminds Bella of the day he first told her he loved her. They’d held hands, fingers entwined as they sat facing each other on a blanket spread across the grass in Kościuszki Park. She was sixteen.

‘You’re it, beautiful,’ Jakob had said softly. His words were so pure, the expression in his hazel eyes so unadulterated, she’d wanted to cry, even though back then she’d wondered what a boy so young thought he knew about love. Today, at twenty-two, she isn’t surer of anything. Jakob is the man she’ll spend her life with. And now he’s leaving Radom, without her.

The clock in the corner sounds a single toll and she and Jakob flinch, as if stung by a pair of invisible wasps. ‘How – how will you get there?’ Her voice is soft. She’s afraid that if she raises it, it will crack, and the sob percolating at the base of her throat will escape.

‘We’ve been told to meet at the train station at a quarter past one,’ Jakob says, glancing toward the door, letting his hands slip from hers. He cups his palms over her knees. His touch is cool through the cotton of her nightgown. ‘I have to go.’ He leans his chest against her shins, rests his forehead on hers. ‘I love you,’ he breathes, the tips of their noses touching. ‘More than anything.’ She closes her eyes as he kisses her. It’s over too quickly. When she opens her eyes, Jakob is gone, and her cheeks are wet.

Bella climbs out of bed and walks to the window, the wooden floorboards cold and smooth beneath her bare feet. Pulling the curtain aside a touch, she stares down at Witolda Boulevard two stories below, scanning for a sign of life – the flicker of a flashlight, anything – but the city has been blacked out for weeks; even the street lamps are extinguished. She can see nothing. It’s as if she’s staring into an abyss. She jiggles the window open, listening for footsteps, for the far-off whine of a German dive-bomber. But the street, like the sky above, is empty, the silence heavy.

So much has happened in a week. It was just six days ago, on the first of September, that the Germans invaded Poland. The very next day, before dawn, bombs began to fall on the outskirts of Radom. The makeshift airstrip was destroyed, along with dozens of tanneries and shoe factories. Her father had boarded up the windows and they’d taken refuge in the basement. When the explosions let up, Radomers dug trenches – Poles and Jews shoulder to shoulder – in a last-minute effort to defend the city. But the trenches were useless. Bella and her parents were forced back into hiding as more bombs were dropped, this time in broad daylight from low-flying Stukas and Heinkels, mostly on the Old Quarter, some fifty metres or so from Bella’s flat. The aerial attack kept up for days, until the town of Kielce, sixty-five kilometres south-west of Radom, was captured. That was when rumours spread that the Wehrmacht, one of the armed forces of the Third Reich, would soon arrive – and when radios began blaring from street corners, ordering the young and able to enlist. Men left Radom by the thousands, heading east in haste to join up with the Polish Army, their hearts filled with patriotism and uncertainty.

Bella pictures Jakob, Genek, Selim, and Adam making their way past the city’s garment shops and iron foundries, treading silently to the train station, which had somehow been spared in the bombings, a few meagre belongings stashed in their suitcases. A division of the Polish infantry, Jakob had said, awaited in Lvov. But did it really? Why had Poland waited so long to mobilise its men? It’s been only a week since the invasion and already reports are disheartening – Hitler’s army is too vast, moving too quickly, the Poles are outnumbered more than two to one. Britain and France have promised to help, but so far Poland has seen no sign of military support.

Bella’s stomach turns. This wasn’t supposed to have happened. They were supposed to be in France by now. That was their plan – to move when Jakob finished law school. He’d find a position at a firm in Paris, or Toulouse, close to Addy; he’d work on the side as a photographer, just as his brother composed music in his spare time. She and Jakob had been charmed by Addy’s tales of France and its freedoms. There, they’d marry and start a family. If only they’d had the foresight to go before travel to France became too dangerous, before the thought of leaving their families behind was too unnerving. Bella tries to picture Jakob with his fingers wrapped around the wooden stock of an assault rifle. Could he shoot a man? Impossible, she realises. He’s Jakob. He isn’t cut out for war; there isn’t a drop of hostile blood in his body. The only trigger he’s meant to press is the one on his camera.

She slides the window gently closed. Just let the boys make it safely to Lvov, she prays, over and over, staring into the velvet blackness below.

Three weeks later, Bella is stretched out along a narrow wooden bench running the length of a horse-drawn wagon, exhausted but unable to sleep. What time is it? Early afternoon, she’d guess. Beneath the wagon’s canvas cover, there isn’t enough light to see the hands of her wristwatch. Even outside it’s nearly impossible to tell. When the rain lets up, the sky, dense with clouds, remains cloaked in gunmetal grey. How her driver can manage up front, exposed to the elements for so many hours, Bella has no idea. Yesterday it rained so long and hard the road disappeared beneath a river of mud, and the horses had to scramble to keep their balance. Twice the wagon had nearly turned over.

Bella tracks the days by counting the eggs remaining in the provisions basket. They began their journey in Radom with a dozen, and this morning they are down to their last, which makes it the twenty-ninth of September. Normally, to ride by wagon to Lvov would take a week at most. But with the incessant rain, the going has been arduous. Inside the wagon the air is damp and smells of mould; Bella has grown used to the feel of sticky skin, clothes that are perpetually damp.

Listening to the creak of the wagon beneath her, she closes her eyes and thinks about Jakob, remembering the night he’d come to say goodbye, the cool of his hands on her knees, the warmth of his breath on her fingers when he’d kissed them.

It was the eighth of September, just a day after he set off for Lvov, when the Wehrmacht arrived in Radom. The Germans sent a single plane first, and Bella and her father tracked it as it flew low over the city, circling once before dropping an orange flare.

‘What does it mean?’ Bella asked as the plane receded and then disappeared into a grey expanse of swollen, low-hanging clouds. Her father was silent. ‘Father, I’m a grown woman. Just tell me,’ Bella had said flatly.

Henry looked away. ‘It means they’re coming,’ he answered, and in his expression, the tight downward curve of his mouth, the pleat of skin between his eyes, she saw something she’d never seen before – her father was scared. An hour later, just as the rain began to fall, Bella watched from the window of her family’s flat as rows upon rows of ground forces marched into Radom, unopposed. She heard them before she saw them, their tanks and horses and motorcycles rumbling in through the mud from the west. She held her breath as they came into view, at once afraid to watch and afraid to look away, her eyes glued to them as they rolled down Witolda Boulevard in bottle-green uniforms and rain-speckled goggles, so powerful, so many of them. They swarmed the city’s empty streets, and by nightfall they occupied the government buildings, proclaiming the city theirs with emphatic Heil Hitlers as they hoisted their swastika flags. It was a sight Bella would never forget.

Once the city was officially occupied, everyone was wary, Jews and Poles alike, but it was obvious from the start that the Jews were the Nazis’ primary targets. Those who ventured out risked being harassed, humiliated, beaten. Radomers learnt quickly to abandon the safety of their homes only to run the most pressing errands. Bella left only once, to collect some bread and milk, detouring to the nearest Polish grocery when she discovered that the Jewish market she used to frequent in the Old Quarter had been ransacked and closed. She kept to the backstreets and walked with a quick, purposeful stride, but on her return she had to step around a scene that haunted her for weeks – a rabbi, surrounded by Wehrmacht soldiers, his arms pinned behind his back, the soldiers laughing as the old man struggled in vain to free himself, his head thrashing violently from side to side. It wasn’t until Bella passed him by that she realised with a sickening start that the rabbi’s beard was on fire.

A few days after the Germans took Radom, a letter arrived from Jakob. My love, he wrote in hurried script, come to Lvov as soon as you can. They’ve put us up in apartments. Mine is just big enough for two. I hate that you are so far away. I need you here. Please, come. Jakob included an address. Her parents, to her surprise, agreed to let her go. They knew how badly Bella missed Jakob. And at least in Lvov, Henry and Gustava reasoned, Bella and her sister Anna could look after one another. Pressing her father’s hand to her cheek in gratitude, Bella was overcome with relief. The next day, she brought the letter to Jakob’s father, Sol. Her parents didn’t have the money to hire a driver. The Kurcs, on the other hand, had the means and the connections, and she was sure they would be willing to help.

At first, though, Sol opposed the idea. ‘Absolutely not. It’s far too dangerous to travel alone,’ he said. ‘I cannot permit it. If anything happened to you, Jakob would never forgive me.’ Lvov hadn’t fallen, but there was speculation that the Germans had the city surrounded.

‘Please,’ Bella begged. ‘It can’t be any worse than it is here. Jakob wouldn’t have asked me to come if he didn’t feel it was safe. I need to be with him. My parents have agreed to it … Please, Pan Kurc. Proszę.’ For three days Bella petitioned her case to Sol, and for three days he refused. Finally, on the fourth day, he acquiesced.

‘I’ll hire a wagon,’ he said, shaking his head as if disappointed in his decision. ‘I hope I don’t regret it.’

Less than a week later, the arrangements were made. Sol had found a pair of horses, a wagon, and a driver – a lithe old gentleman named Tomek, with bowed legs and a greying beard, who had worked for him over the summer and who knew the route well. Tomek was trustworthy, Sol said, and good with horses. Sol promised him that if he brought Bella safely to Lvov, he could keep the horses and wagon. Tomek was out of work and jumped at the offer.

‘Wear the things you want to take,’ Sol had said. ‘It will be less conspicuous.’ Civilian travel was still allowed in what was once Poland, but the Nazis issued new restrictions by the day.

Bella wrote immediately to Jakob, telling him of her plans, and left the following day, wearing two pairs of silk stockings, a navy knee-length fluted skirt (a favourite of Jakob’s), four cotton blouses, a wool sweater, her yellow silk scarf – a birthday gift from Anna – a flannel coat, and her gold brooch, which she hung on a chain around her neck and tucked into her shirt so the Germans wouldn’t see it. She slipped a small sewing kit, a comb, and a family photo into her coat pocket beside the forty zloty Sol insisted she bring. Instead of a suitcase, she carried Jakob’s winter jacket and a hollowed loaf of peasant bread with his Rolleiflex camera hidden inside.

They’ve crossed four German checkpoints since leaving Radom. At each, Bella tucked the bread loaf beneath her coat and feigned pregnancy. ‘Please,’ she begged, one hand resting on her belly, the other on the small of her back, ‘I must reach my husband in Lvov before the baby arrives.’ So far, the Wehrmacht has taken pity on her, and waved the wagon on.

Bella’s head rocks gently on the bench as they plod eastward. Eleven days