Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

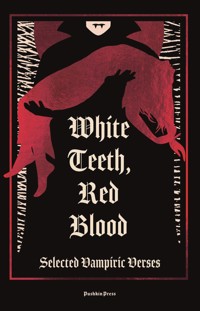

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Poems to make your blood run cold. Poems to make your heart beat faster. Poems to sink your teeth into... Three centuries of vampiric verse. Seductively sinister, both frightening and alluring, the undead have always been the perfect vessel for humanity's fears and desires. The poems in this collection of dark delights range across centuries and languages; poems that tell stories, offer warnings, and imagine life in the shadows, by writers such as Lord Byron, Emily Dickinson, Charles Baudelaire, Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Ishmael Reed, and many more. With an introduction by Claire Kohda, author of Woman, Eating. Contents include: Chilling Tales - poems by Gottfried August Burger, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Robert Southey, Anne Bannerman, John Stagg, Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Rafael Campo Dire Warnings - poems by Heinrich August Ossenfelder, John Keats, Henry Thomas Liddell, James Clerk Maxwell, Charles Baudelaire, Christina Rossetti, Madison Julius Cawein, Rudyard Kipling, Conrad Aiken, Edna St Vincent Millay, James Weldon Johnson The Vampire Within - poems by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, Emily Brontë, Emily Dickinson, Walter Pater, Delmira Agustini, William Butler Yeats, Ishmael Reed, Dorothy Barresi, John Yau

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 166

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

1

2

3

Contents

Introduction

When I was asked to introduce this book, I thought that I was perhaps the worst person to do so. I didn’t grow up reading vampire fiction, or horror, and I wouldn’t consider myself a vampire fan, even though I have written a novel whose main character is a vampire.

I think, however, that very few of the authors represented in these pages wrote about vampires because they were vampire fans. Byron likely wasn’t obsessed with vampires (though one of the earliest literary vampires is based on him). Neither was Emily Dickinson, and probably neither was Kipling (though he, of everyone included in this book, is to my mind the most likely to have actually been a vampire; at least, with the colonialist, exoticizing and fetishizing under(over) tones of his work, he is one of the most vampiric). All the writers in this book, rather, were drawn to the vampire as a metaphor or device.

The vampire, for a writer, is an alluring figure. It straddles life and death, is often nocturnal, or at least inhabits shadows or the dark, and must drain living things of blood in order to survive. It is a creature that looks like us humans but has a different diet; it is a slightly different species, but one that can exist amongst humans undetected. In essence, it is different, other. Loneliness, alienation, morality, mortality, humanity, 10inhumanity: all can be explored through the vampire, plus any form of difference: neurodivergence, foreignness, disability, illness, gender and sexuality, for instance. Vampires are also full of contradictions. Alive, but dead; often beautiful, but abhorrent; sometimes sexy, despite having been dead for centuries; self-flagellating and hungry; powerful, superhuman, yet sometimes vulnerable and fragile. Very old vampires are anachronisms: they are living history, bringing the past right into the present, with all the traumas of the past. Every one of us who has written about a vampire knows our own vampire very well, because each reflects something of what we thought of humanity at the time we wrote them. But perhaps none of us could do justice to introducing this book.

A vampire is defined differently depending on who you speak to. Many cultures have blood-sucking creatures in their mythologies. The Balinese léyak, for instance, appears human during the day, but after dark, its head and internal organs break away from their body and fly through the night looking for newborn babies to drain of blood. The langsuyarof Malaysia is a woman who becomes a flying vampire-like creature after the stillbirth of her child; while the pontianakis a woman who has died during childbirth and feasts on the blood of men. The sasabonsamof Ghana hangs upside down from trees like a bat, then swoops down and eats its victims, thumbs first. Then there is the yara-ma-yha-who, a creature from Australian Aboriginal folklore that resembles a small frog-like man who drains its victims’ blood using suckers 11on its hands and feet. The vampire in this collection is the Western vampire: the bloodsucker who bites victims’ necks, drains blood to survive, is human in appearance, immortal, and whose lineage includes figures such as Dracula and Nosferatu.

However, all these creatures are related. Often colonialism creates new vampires, such as the soucouyantof the Caribbean; myths from different cultures combine to create new monsters; and often their bloodsucking stands for the real-life draining of a country’s and a people’s culture and resources. Vampire-like myths have also travelled back to the West and come to represent in the Western mind fear of the other, of difference, immigration, the foreigner, and of revenge by colonial and/or enslaved subjects. Bloodsuckers are in this way often cousins.

You can read this collection in any order. However, it is divided into three sections. “Chilling Tales” contains unsettling poems that you can imagine reading by candlelight, including many long narrative poems from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, an under-read and overlooked form. “Dire Warnings” sees the wrath of a vampire often imagined as punishment for war-mongering, sexual promiscuity, or for a woman rejecting a man, the latter in Heinrich August Ossenfelder’s violent poem TheVampirefrom 1748, in which the male protagonist imagines himself as a vampire sneaking into a woman’s room after she has rejected him, and taking “her life’s blood”. In “The Vampire Within”, the vampire is less definable. In the often more interior and 12insular poems here, it acts as a metaphor for many things, from pregnancy and art to racism and colonialism.

These sections are chronological, charting the evolution of the Western vampire from its early origins to its most recent incarnations. I began at the end and worked backwards, starting with the vampire closest to my own, in time and in origin—a 2022 vampire in Chinese-American poet, art critic and curator John Yau’s CharlesBaudelaireandIMeetintheOvalGarden. The dual identities of the vampire intrigue me: dead/ alive, inhuman/human, other/familiar; and Yau’s writing often explores the dualities of East and West, of visual art and writing. Here, Yau writes a Malaysian verse form called a pantoum, popular with nineteenth-century French poets, in which the second and fourth lines become the first and third lines in the next stanza, giving the poem a woven quality. One line reads: “They say that the latest strain hiding in the shadows is a yellow vampire”—an allusion, perhaps, to the Covid-19 pandemic during which people of Asian descent were subjected to hate and blamed for the virus; the monstrousness of the vampire represents the virus itself and the dehumanization of Asians at the time. Further back, in Ishmael Reed’s singingly musical 1972 poem, IAmaCowboyintheBoatofRa, the vampire is Set (god of, among much else, violence and foreigners), and he symbolizes the suppression of native religions by foreign powers, an “imposter” and “usurper”, a “party pooper O hater of dance”. The protagonist goes out after him, “to unseat Set”, “to Set down Set”. Neither Reed’s nor Yau’s poem is of the horror genre; 13but the inclusion of the vampire highlights the horrors of humanity.

Walter Pater’s famous description of the MonaLisaisn’t strictly a poem but rather a paragraph lifted from his essay on Leonardo da Vinci in his 1873 book TheRenaissance:StudiesinArtandPoetry; though W.B. Yeats described it as “the first modern poem” and published a sentence from it (beginning “She is older than…”), broken up into lines to more closely resemble poetry, in TheOxfordBookofModernVersein 1936. In this original version, the Mona Lisa is a “vampire”: timeless, immortal, containing “all the thoughts and experience of the world… the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome…”, “older than the rocks among which she sits”. The Mona Lisa as vampire is a comment on art, not just this portrait—but the mysterious vitality at the centre of all works of art that, as if by magic, connect us to and preserve the past, while continuing to comment on the present.

The boundaries between life and death (and life again) are blurry for vampires. Emily Dickinson’s 1866 poem ADeathblowisaLifeblowtoSomecan read on the surface like a vampire poem where the life–death boundary is blurred, but also uses the idea of returning to life after a “death blow” to deliver a message: don’t wait until death comes to truly start living. Anna Lætitia Barbauld’s ToaLittleInvisibleBeingfocuses on the divide between life and death too, but addresses an unborn child, still in the womb, waiting to arrive: “Haste,” she writes, “through life’s mysterious gate”. And then, in American poet and physician Rafael Campo’s 1994 poem TheDistantMoon, a 14doctor takes care of a dying patient; the vampire is only a brief metaphor in passing—the doctor drawing blood, “You’ll make me live forever!” says the patient. “The darkened halls” here are not of a vampire’s manor but of a hospital, but just as occupied by both life and death; “he was so near / Death” reads one line break which can be read in many ways: the patient physically close to the doctor, Death metaphorically close to the patient, the patient nearly gone and, so, in fact, getting more distant from the doctor.

The vampire is often a woman—a sinful temptress or witch – who preys on men. Conrad Aiken’s TheVampire, written in 1914, characterizes war as a female vampire possessing “terrible beauty”, perhaps also alluding to suffragettes, who at the time were seen as terrorists. The men in this poem give in to her, “with mouth so sweet, so poisonous”, until the ground is strewn with bodies and a ploughman is driving “through flesh and bone”. In Madison Julius Cawein’s 1896 poem, the speaker is seduced, then bound by “witch-words… to a fiend / Until I die”. But go back to 1816, and in the section “Chilling Tales” is one of several long story-poems in this collection: the eerie, gothic, unfinished ballad Christabelby Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Here the vampiric figure Geraldine is a woman, as is Christabel, her victim. This is a sexually suggestive poem; Christabel falls under Geraldine’s spell, undresses and lies down with her. In Coleridge’s time, this would have been read as Christabel having been tempted into – or compelled into – sin, into lesbianism. However, Geraldine is a complex vampiric figure. She comes across as a temptation rather than 15a straightforward threat, and her encounter with Christabel is secretive, but not unpleasant. When Geraldine undresses, it reads, “Behold! her bosom and half her side – / A sight to dream of, not to tell!” Contrasting with Ossenfelder’s The Vampire, in which a man fantasizes about draining his victim’s “life’s blood” and vampirism very explicitly suggests sexual violence, Geraldine is depicted holding Christabel: “in her arms the maid she took”.*

The earliest ghoul (not quite vampire) in this collection is male. Gottfried August Burger’s 1774 poem Lenore–together with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1797 poem TheBrideofCorinth–was an inspiration for a lot of early vampire literature, including Bram Stoker’s Dracula (which quotes the line “the dead travel fast” or “die Todten reiten schnell”, translated here by Dante Rossetti as “the dead gallop fast”).In Lenore,a soldier called William returns from the dead to his grieving wife and whisks her off on horseback to a cemetery where his human visage falls away, revealing that, underneath, he is Death, “fleshless and hairless… The lifelike mask was there no more”. The Earth itself responds: “Groans from the earth and shrieks in the air! Howling and wailing everywhere!” Many consider this poem the origin of Western 16vampire literature – yet there is no bloodsucking, there are no fangs; just grief, horror and the sense of something deeply wrong. The vampire endures as a literary device because this is what is at its heart; it is a creature that evokes the most horrifying and often difficult aspects of human life. In the opposites that exist so close to the surface in a vampire – terror, violence, repulsion and monstrousness, alongside love, romance, attraction and beauty – are reflected something of the incomprehensibility of our world.

claire kohda

* Lord Byron read Christabelaloud to his guests in a house on Lake Geneva in 1816. Percy Shelley, one of the guests, had to leave the room after a couple of lines and be treated by a doctor. From that came the idea for everyone present to write a scary story. John William Polidori wrote an influential short story called TheVampyre, basing his vampire on Byron; Byron wrote several poems, and Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (later Mary Shelley) wrote Frankenstein, considered by many the first science fiction novel.

ChillingTales

Lenore

GOTTFRIED AUGUST BURGER

1774

TranslatedbyDanteGabrielRossetti

Up rose Lenore as the red morn wore,

From weary visions starting;

“Art faithless, William, or, William, art dead?

’Tis long since thy departing.”

For he, with Frederick’s men of might,

In fair Prague waged the uncertain fight;

Nor once had he writ in the hurry of war.

And sad was the true heart that sickened afar.

The Empress and the King,

With ceaseless quarrel tired,

At length relaxed the stubborn hate

Which rivalry inspired:

And the martial throng, with laugh and song,

Spoke of their homes as they rode along,

And clank, clank, clank! came every rank,

With the trumpet-sound that rose and sank.

And here and there and everywhere,

Along the swarming ways,

Went old man and boy, with the music of joy,

On the gallant bands to gaze;20

And the young child shouted to spy the vaward,

And trembling and blushing the bride pressed forward:

But ah! for the sweet lips of Lenore

The kiss and the greeting are vanished and o’er.

From man to man all wildly she ran

With a swift and searching eye;

But she felt alone in the mighty mass,

As it crushed and crowded by:

On hurried the troop,—a gladsome group,—

And proudly the tall plumes wave and droop:

She tore her hair and she turned her round,

And madly she dashed her against the ground.

Her mother clasped her tenderly,

With soothing words and mild:

“My child, may God look down on thee,—

God comfort thee, my child.”

“Oh! mother, mother! gone is gone!

I reck no more how the world runs on:

What pity to me does God impart?

Woe, woe, woe! for my heavy heart!”

“Help, Heaven, help and favour her!

Child, utter an Ave Marie!

Wise and great are the doings of God;

He loves and pities thee.”

“Out, mother, out, on the empty lie!

Doth he heed my despair,—doth he list to my cry?

What boots it now to hope or to pray?

The night is come,—there is no more day.” 21

“Help, Heaven, help! who knows the Father

Knows surely that he loves his child:

The bread and the wine from the hand divine

Shall make thy tempered grief less wild.”

“Oh! mother, dear mother! the wine and the bread

Will not soften the anguish that bows down my head;

For bread and for wine it will yet be as late

That his cold corpse creeps from the grim grave’s gate.”

“What if the traitor’s false faith failed,

By sweet temptation tried,—

What if in distant Hungary

He clasp another bride?—

Despise the fickle fool, my girl,

Who hath ta’en the pebble and spurned the pearl:

While soul and body shall hold together

In his perjured heart shall be stormy weather.”

“Oh! mother, mother! gone is gone,

And lost will still be lost!

Death, death is the goal of my weary soul,

Crushed and broken and crost.

Spark of my life! down, down to the tomb:

Die away in the night, die away in the gloom!

What pity to me does God impart?

Woe, woe, woe! for my heavy heart!”

“Help, Heaven, help, and heed her not,

For her sorrows are strong within;

She knows not the words that her tongue repeats,—

Oh! count them not for sin!22

Cease, cease, my child, thy wretchedness,

And think on the promised happiness;

So shall thy mind’s calm ecstasy

Be a hope and a home and a bridegroom to thee.”

“My mother, what is happiness?

My mother, what is Hell?

With William is my happiness,—

Without him is my Hell!

Spark of my life! down, down to the tomb:

Die away in the night, die away in the gloom!

Earth and Heaven, and Heaven and earth,

Reft of William are nothing worth.”

Thus grief racked and tore the breast of Lenore,

And was busy at her brain;

Thus rose her cry to the Power on high,

To question and arraign:

Wringing her hands and beating her breast,—

Tossing and rocking without any rest;—

Till from her light veil the moon shone thro’,

And the stars leapt out on the darkling blue.

But hark to the clatter and the pat pat patter!

Of a horse’s heavy hoof!

How the steel clanks and rings as the rider springs!

How the echo shouts aloof!

While slightly and lightly the gentle bell

Tingles and jingles softly and well;

And low and clear through the door plank thin

Comes the voice without to the ear within: 23

“Holla! holla! unlock the gate;

Art waking, my bride, or sleeping?

Is thy heart still free and still faithful to me?

Art laughing, my bride, or weeping?”

“Oh! wearily, William, I’ve waited for you,—

Woefully watching the long day thro’,—

With a great sorrow sorrowing

For the cruelty of your tarrying.”

“Till the dead midnight we saddled not,—

I have journeyed far and fast—

And hither I come to carry thee back

Ere the darkness shall be past.”

“Ah! rest thee within till the night’s more calm;

Smooth shall thy couch be, and soft, and warm:

Hark to the winds, how they whistle and rush

Thro’ the twisted twine of the hawthorn-bush.”

“Thro’ the hawthorn-bush let whistle and rush,—

Let whistle, child, let whistle!

Mark the flash fierce and high of my steed’s bright eye,

And his proud crest’s eager bristle.

Up, up and away! I must not stay:

Mount swiftly behind me! up, up and away!

An hundred miles must be ridden and sped

Ere we may lie down in the bridal-bed.”

“What! ride an hundred miles to-night,

By thy mad fancies driven!

Dost hear the bell with its sullen swell,

As it rumbles out eleven?”24

“Look forth! look forth! the moon shines bright:

We and the dead gallop fast thro’ the night.

’Tis for a wager I bear thee away

To the nuptial couch ere break of day.”

“Ah! where is the chamber, William dear,

And William, where is the bed?”

“Far, far from here: still, narrow, and cool;

Plank and bottom and lid.”

“Hast room for me?”—“For me and thee;

Up, up to the saddle right speedily!

The wedding-guests are gathered and met,

And the door of the chamber is open set.”

She busked her well, and into the selle

She sprang with nimble haste,—

And gently smiling, with a sweet beguiling,

Her white hands clasped his waist:—

And hurry, hurry! ring, ring, ring!

To and fro they sway and swing;

Snorting and snuffing they skim the ground,