7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

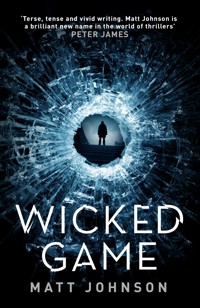

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Robert Finlay

- Sprache: Englisch

Royalty Protection Team officer Robert Finlay is looking forward to a quieter life, when two police officers are killed and their links to his own past becomes clear … putting everyone's lives in danger. A startlingly authentic debut … first in a page-turning, searing new series. **NUMBER ONE BESTSELLER** **Shortlisted for the CWA John Creasey New Blood Dagger** **LoveReading Debut of the Month** 'Terse, tense and vivid writing. Matt Johnson is a brilliant new name in the world of thrillers. And he's going to be a big name' Peter James 'From the first page to the last, an authentic, magnetic and completely absorbing read' Sir Ranulph Fiennes ____________________ 2001. Age is catching up with Robert Finlay, a police officer on the Royalty Protection team based in London. He's looking forward to returning to uniform policing and a less stressful life with his new family. But fate has other plans. Finlay's deeply traumatic, carefully concealed past is about to return to haunt him. A policeman is killed by a bomb blast, and a second is gunned down in his own driveway. Both of the murdered men were former Army colleagues from Finlay's own SAS regiment, and in a series of explosive events, it becomes clear that he is not the ordinary man that his colleagues, friends and new family think he is. And so begins a game of cat and mouse – a wicked game, in which Finlay is the target, forced to test his long-buried skills in a fight against a determined and unidentified enemy. Wicked Game is a taut, action-packed, emotive thriller about a man who might be your neighbour, a man who is forced to confront his past in order to face a threat that may wipe out his future, a man who is willing to do anything to protect the people he loves. But is it too late? ____________________ 'Utterly compelling and dripping with authenticity. This summer's must-read thriller' J S Law 'Out of terrible personal circumstances, Matt Johnson has written a barnstormer of a thriller. Nothing is clear-cut in a gripping labyrinthine plot, which – despite thrills and spills aplenty – never falls short of believable' David Young 'Wicked Game has the authenticity I look for in a thriller. While the plot kept me turning pages, the characters made me care. Matt writes like a man who has lived it' Kevin Maurer 'Johnson litters his tale with the plotting equivalent of incendiaries: cops we don't quite trust, a career that came abruptly to an end, a secret needing to be kept … Gripping stuff' New Welsh Review

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 583

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Wicked Game

Matt Johnson

Dedicated to the memory of Police Inspector Stephen Dodd, Sergeant Noel Lane, PC Jane Arbuthnot and Police Dog Queenie, and to my friend PC Yvonne Fletcher.

Colleagues never to be forgotten.

‘To keep your secret is wisdom; but to expect others to keep it is folly.’Samuel Johnson (1709–1784)

Contents

Prologue

August 2001. Kalikata, India

Jed Garrett and Mac Blackwood stepped out of the artificially cool aircraft cabin into a wall of heat.

There was no shelter from the Indian sun and no breeze to provide even the smallest relief. Their faces flushed and moist, both men realised that their decision to wear jackets and ties had been a mistake. The monsoon season was nearing an end but Garrett knew they would have to endure this discomfort for another month at least.

‘Fucking hell, Jed, what is that smell?’ asked Blackwood, as they joined the other passengers on the short, stifling walk across the tarmac to the waiting airport bus.

Garrett had smelled Kalikata before. Sweat, exhaust fumes and local spices combined to produce a pungent, musty aroma that some loved but many found hard to bear.

‘That’s the smell of India, Mac. Get used to it, we’re gonna be here a while.’

As they boarded the bus, Garrett could see his friend becoming impatient. He was anxious to get to their hotel and get their business underway. Garrett smiled. Mac was going to have to adjust to the slower pace of life here. The perpetual heat and humidity would soon put paid to any ideas of doing things quickly. Mac Blackwood was used to the chilly, windswept streets of Glasgow, whereas Garrett was from Florida and had been to India many times before.

In the welcome air-conditioned atmosphere of the arrivals hall, Mac relaxed again.

‘No wonder they call this the black hole of Calcutta,’ he said pointing through the window to the crowds who stood outside waiting to beg from, or sell to, the arriving travellers. There were hundreds of them. Men, women and children of all ages. Kids with filthy hands, blackened nails and puppy-dog eyes chased around, pleading for small change from the tourists.

‘I fuckin’ hate this place already.’ Blackwood turned away from the window. ‘Ach, for Christ sake. Look at the state of that kit.’ He pointed to the uniforms of the soldiers who milled around the airport concourse, trying to look efficient.

Garrett was starting to get tired of his companion’s constant moaning. He stayed silent until their bags appeared on the carousel.

Outside, he hailed a taxi. But as the driver took their bags, children surrounded them, their tiny hands open and extended. ‘Gimme dollar, gimme dollar.’

One youngster held up a soiled copy of Penthouse. ‘You buy, you buy,’ he called.

As Mac Blackwood reached for his pocket, Garrett grabbed his arm and pulled him towards the car. He knew giving just one child some cash would mean another fifty blocking their way.

‘Oberoi Hotel,’ he told the driver.

Blackwood had to prise tiny fingers from the door handle before he could join Garrett in the back. They accelerated slowly away, stained and grimy hands smacking incessantly on the windows as the taxi driver sought out a route through the throng.

With the noise and bustle of the airport fading away behind them, Garrett sighed and shook his head at Blackwood. ‘Over three million kids die ever year in this country from diseases caused by poverty,’ he said. ‘They’ll do whatever they can to survive. Help one, and they’ll all want a piece of you.’

Blackwood simply nodded. Not helping a needy kid didn’t sit comfortably with him.

They had been travelling for only a minute or two when the taxi started to slow.

‘What now?’ Blackwood leaned forward. The taxi driver was stopping to let a cow cross the road.

‘Cows are sacred here, Mac,’ said Garrett, putting a hand on his friend’s shoulder. ‘Just be patient.’

At that moment, the front passenger door swung open and a filthy teenager in a simple shirt and trousers jumped in. The first thing Blackwood noticed was the smell. Garrett saw the holdall the kid carried.

‘American?’ The boy smiled as he turned to ask them the question.

‘Canadian,’ Garrett lied. Canadians were popular everywhere.

‘Have a nice day.’

The last thing Jed Garrett saw were the two wires that stuck out from the side of the bag the boy was carrying and the swift movement as he reached down to press them together.

The explosion tore the car apart.

Debris rained down, clattering over the road and sending onlookers scurrying for shelter.

Even before the smoke had cleared, barefooted men had begun to claw over the Westerners’ luggage. Some gawped at the scorched and mutilated figures that hung from the wrecked car.

Nobody tried to help them.

Chapter 1

As Costello watched the scene, he smiled. It was a twisted, sadistic expression. The smile of a killer experiencing a cruel sense of satisfaction at a job well done.

The window of the factory office allowed him a clear view of the local police as they started to close the road and move the looters away from the smoking wreck of the taxi. Nobody made any effort to give first aid to the occupants. There was no point: the explosive had done its job.

The door on the far side of the office opened. It was Malik, the local contact.

‘The airport will be closed for a short while, Declan. Do you want me to arrange some lunch for you?’

As Costello turned away from the window, his smile became a scowl. ‘How old was the boy you used?’

Malik shrugged. ‘He was nothing, do not trouble yourself. Just faqir, a street beggar. We gave his family many rupees. They will not miss having his troublesome mouth to feed.’

‘Really? I don’t get it.’

‘Our lives are not ours to decide, Declan. That is for God. We are but pawns.’

‘You speak for yourself, Malik. Where I come from we value our lives.’

‘And where is that, Declan? You have a very strange accent if you don’t mind me saying. Are you from Manchester?’

Costello smiled. He sounded nothing like a Mancunian. ‘Yes,’ he lied. ‘Manchester.’

‘Here, we are loving your football. Manchester United is very strong in India.’

‘I bet they are. Now, about that food. My flight takes off in three hours. That should give me plenty of time to check-in and then get a bite afterwards. Do you know a way around that mess outside?’

‘Not to worry, Declan. I will get you a tuk-tuk. He will take you back road to departure lounge so you have time to eat before flight.’

Costello turned back to the window. The first ambulance had arrived. Everywhere he looked scooters and small motorbikes darted and weaved through the congested traffic. It was a warm day, sticky and humid. The thought of a trip in one of the three-wheeler motorised rickshaws didn’t fill him with enthusiasm.

‘Can you get me a taxi?’ he asked. ‘And one with air-con that actually works.’

‘Mr Yildrim said I should give you whatever you need, Declan. I will make the arrangement.’ Malik pressed his hands flat together in a prayer position and raising them in front of his face, bowed gently, then turned back through the door.

Costello smiled. Yildrim would be pleased. His new employer was a fixer, an arranger. He had organised the job and identified the target. Costello did the work on the ground. Their clients were the kind of people who wanted things done quickly and effectively and paid well for the service. Very well, Costello reflected. But then the skills and expertise they were buying weren’t the kind to be found just anywhere. They were paying to have people killed, and that kind of service came at a high price.

His first meeting with Yildrim had been set up just a few weeks ago by an IRA intermediary. It had started badly. Costello had made the mistake of saying he thought he recognised the Arab. That had made Yildrim uncomfortable and for a minute or two it looked like the job was lost. Fortunately, when Costello speculated that they might have met at a training camp in Pakistan, the Arab had relaxed. He had indeed been there, to instruct young volunteers on techniques for making road-side bombs. They agreed it was quite possible that he had been Costello’s instructor.

Costello wasn’t sure, though. He certainly didn’t remember the name ‘Yildrim’. In the end, he had deemed it wise not to press the point. People like Yildrim used many false names. The less Costello knew about his new contact, the safer he would be.

The rest of their conversation ran like a job interview. The work that Yildrim was offering was lucrative and had to be completed soon. He gave no explanation for the urgency but asked Costello a lot of technical questions. For his part, Costello explained his experience, his methods and provided the name of a mutual acquaintance who could vouch for his competence. Their shared experience at the Pakistan training camp seemed to swing it. He was offered the job.

Blackwood was the first target. Garrett had simply made a bad choice of travelling companion. The two men were ex-military instructors. A local militia group had hired them to teach volunteers how to plant mines, lay booby traps and use plastic explosive. Malik had discovered the pair’s travel arrangements and had been instrumental in arranging the interception.

So now, phase one was complete. Yildrim had made it easy – Malik had done all the work, and would probably have been capable of dealing with Blackwood himself, but the Arab had insisted Costello travel to India to supervise the attack.

Yildrim had warned him that the remaining targets would be a lot harder.

As he continued to watch through the factory window, Costello could see that the airport approach road was now grid-locked. The air was filled with the constant sounding of car and motorcycle horns. Street vendors and beggars were taking advantage of the opportunity, moving from car to car, banging on windows to try and persuade frustrated motorists to part with a few rupees. Any car with a rearseat passenger was singled out for particular attention.

Costello turned to his bag, which sat on a nearby chair. He unzipped it. The flight back to the UK would be a long one. A change and stop-over in Dubai meant the best part of fourteen hours in the air. He was travelling light, just a change of clothing and some cash. He reached inside and checked for his passport and plane ticket. They were there.

If everything in the UK had gone to plan, all the necessary weapons and explosive should now be stored and ready for use.

Inside a week, he and his friends would be on their way home with the job complete.

Chapter 2

August 2001. Police firing range, Old Street Police Station, London.

I rolled heavily over on my left side and then onto my stomach. The wooden floor rubbed my elbows. As I heard the noise from the motorised turning target, I raised the Beretta.

The smoke in the ‘ambush simulation’ range obscured my vision and choked my lungs. Pre-recorded gun-fire and screams conspired to confuse my senses, but I’d done this too many times before. The target was a ‘friendly’ – a woman holding a kid. Catching my breath for a moment, I held fire. A split second later there was a noise to my left. I rolled again.

Christ, I was getting too old for this. As I got back on to my knees, I caught a glimpse of an AK47-toting terrorist about twenty feet away, half obscured by a wall. I aimed quickly, fired three rounds and rolled again to take cover behind a mock wall.

The background noise stopped and extractor fans started up. As I stood, the lights came on and the smoke began to clear. My knees and shoulders ached. I arched my back to ease the discomfort.

Two policemen, wearing blue working uniform and berets, joined me as I unclipped the magazine from the Beretta and cleared the chamber. I squeezed the unused round into the magazine. With the pistol held safely in my shoulder holster I started to brush the dust from my clothes.

‘Very good, Finlay.’ Chief Inspector Gooding, immaculate in pressed blue shirt and trousers, shiny brogues and departmental tie, approached me. He made a note on a clipboard before folding it under his arm.

‘Thanks, I do my best.’ I smiled to avoid showing the pain my shoulders were causing me.

‘You scored ninety per cent, as usual. I will never understand why you insist on losing marks by firing three rounds at each target rather than two.’

‘Old habit, I guess.’ I was still breathing heavily, the smoke taking a while to clear from my lungs.

‘Well, you’ve passed your re-test, although I’m told that it’s academic: you’re leaving Royalty Protection and going back to division soon, aren’t you?’

The Chief Inspector escorted me to the armourer where I was required to store my pistol while I took a shower. He shook my hand firmly and wished me luck for the future. I wasn’t surprised to find out that he knew about my application. Rumours spread quickly in our job. I’d been a policeman for more than sixteen years, the last three in Royalty Protection. If there was one thing I had learned in that time, it was that it was impossible to keep anything secret for long.

I headed for the changing rooms. After a quick shower, I recovered my beloved Beretta, holstered it and buttoned my blazer.

I had good cause to be fond of that pistol. A standard military M9, it used 9mm ammunition, had a fifteen-round magazine and was fitted with military dot-and-post sights. The magazine capacity was the reason I preferred triple taps, three rounds at each target. Three into fifteen went easily. All I had to do was count five and I knew it was time to re-load. Plus the M9 had a smooth recoil and was easy to take apart, be it in the dark or in the field.

As I headed out into the street, the weather was glorious, warm with a slight breeze. I paused for a moment, enjoying the feel of the sun on my face. It reminded me a lot of the day when a similar Beretta had been the friend that had saved my hide.

Chapter 3

5th January 1980. Northern Ireland. Armoury of a combined RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) and Army base.

‘Travelling alone boss?’ The Quartermaster Sergeant seemed concerned that I had no escort.

‘Yeah, a meeting with the RUC. They want to chat about a new cell operating in the area and about the contact outside Castlederg last week. I should be back before eleven hundred hours.’

I understood his concern, it was standard procedure to travel in pairs. I also knew that two fit-looking men in a car would be far more likely to be identified as soldiers than a scruffy-looking individual on his own.

That day, as I booked out my personal weapon, I had no idea how attached to it I was going to become. Even in those days, I preferred the Beretta over the standard issue Browning and, luckily for me, I was allowed the choice. At the time though, it was just a tool of the job. Nothing to be fond of.

In January 1980, I was twenty-seven years old. I’d been in the army for eight years, having signed on for a three-year, short-service commission after flunking my ‘A’ levels. My grammar school headmaster had been so surprised when he’d heard the news that he had actually rung my parents to see if it were true. ‘Robert Finlay an army officer? Never!’ I could just imagine his words. But he had only known me as a kid who seemed to have more time for girls than his studies. I could remember his words clearly from when he lectured me the second time I was given the cane. ‘Study now, fornicate later, Finlay,’ he said. I should have listened but, hell, I was sixteen, no-one could teach me anything.

I enjoyed the army so much that instead of leaving after three years, I signed on for a regular commission. The last three of my eight years’ service had been spent as a troop commander in various parts of the world with the 22nd SAS Regiment.

I hadn’t always wanted to try SAS selection. It was only when I met some of their lads on a training exercise in Germany that the idea entered my head. Generally speaking, artillery officers don’t apply for Special Forces. My application surprised even my closest friends in the mess at Woolwich.

Although I made it through the selection process at the first attempt, I was a long way from being the best applicant the SAS ever had. And this was amply demonstrated by the hill-phase endurance test. It’s ironically called the Fan Dance. Forty-five miles on foot in twenty hours, carrying so much kit that most men needed help simply to stand up.

After crossing the finish line with just a few minutes to spare, I developed both a deep respect and hatred of the Brecon Beacons, the range of mountains where the test took place. It’s a beautiful place, incredible scenery and wonderful landscape, but I always seemed to see it through a fog of pain.

To this day, I don’t really remember the last five miles. I just kept moving forward, my brain in a form of numbed haze. I passed four casualties in the final stages, including another of the three officer candidates, a Captain from the Royal Irish Rangers.

Perhaps I was stupid, but I lost time as I stopped to speak to all of them to see if they needed help. One of the lads from the Engineers had collapsed face-down near a stream. Poor bastard was being weighed down by his bergen and would probably have drowned if I hadn’t come around the corner. I wasted several minutes dragging him into the shelter of a rocky outcrop before trudging on.

A few yards after crossing the line, my legs gave up the fight and I ended up on my back, bergen beneath me, flailing about like a stranded beetle. Strong hands helped me to my feet and a mug of tea was shoved into my hand. The corporal who handed it to me laughed at my reaction to the super-sweet liquid.

‘Get it down you, butt,’ he barked.

‘You’re Welsh?’ I said as I took a second gulp.

‘From the valleys.’

‘My mother’s from Swansea.’

‘Like I give a shit. Now get moving, on the lorry and double quick,’ came the reply.

I’d been put in my place. Officer or not.

Over the coming year I spent all my time on the shooting range, in the jungle, on escape and evasion exercises or acquiring the skills needed on the counter-terrorist team.

I made the cut, and in late 1978 was assigned to B squadron.

Chapter 4

5th January 1980. Northern Ireland

It was just before seven a.m. when I stopped at the perimeter checkpoint before pulling out into the main street. The police guard looked closely at my pass and then at me. I guessed he was comparing the pristine facial features on the photograph to the curly hair and suntan I was then sporting. Like I always did at the gate, I winked.

With only the vaguest hint of a smile, the guard nodded me through. I hid the pass behind the dash of the Rover. The meeting with the RUC bosses was at nine. I’d figured the drive should take me about an hour. That would leave me plenty of time to sample the police canteen’s excellent breakfast.

That day I was in plain clothes; it helped to avoid being noticed. The terrorists had spotters everywhere. Dickers, we called them. Often they were impossible to recognise. One might look like a schoolgirl, another like a postman.

The previous day, an Air Corps Sergeant had offered me an early ride to the meeting in a helicopter, but hell, I enjoyed driving and it had promised to be a beautiful day. With hindsight, I should have taken that heli.

As I neared the edge of the town I was waved straight through the vehicle checkpoint at the entrance to the main ‘A’ road. I eased down the accelerator, the smooth, powerful V8 engine bringing the Rover effortlessly up to seventy. The Rover was bog standard, apart from the Kevlar fitted to the rear of the seats and inside the doors. Kevlar was light, bullet-proof and didn’t affect the car’s performance. It wouldn’t stop armour-piercing rounds but it certainly gave me some reassurance.

As a member of mobility troop, I’d had some advanced driver training. I’d never been that good a driver, though, I didn’t have the concentration. I could do some of the tricks, handbrake turns, that sort of stuff, but wasn’t an expert like some of the guys. Given the choice, in a scrape I’d leave the driving to someone else. I was better at talking.

We changed the external appearance of the Rover as often as possible. Number plates and tax disc came first, vinyl roof at other times. Paint was more difficult, but at least once a month someone found himself looking for the wrong-coloured car when he needed it in a hurry.

I slowed down to sixty as the road narrowed to a single lane.

The weather forecast was right. It looked like being a nice day in the province, blue skies, a gentle breeze and with the odd cloud. Like I said, my favourite kind of day.

Approaching Drumquin, I spotted a blue Mk2 Cortina waiting at a side junction. To this day, I don’t know if it was curiosity or a sense of self-preservation that made me take a second look at the occupants. There were three. All men, all late teens or early twenties, all in casual clothes. They didn’t look directly at me, but the one in the back caught my eye. He looked hard at the Rover and then started writing something down.

I eased off the gas and watched them carefully in the rear-view mirror. The Cortina pulled out and drove off in the opposite direction.

I had just started to relax when I saw the rear-seat passenger turn his head around. He was watching me. A dicker.

The hairs on the back of my neck stood on end.

It was just before eight when I arrived at Castlederg. For the whole journey I’d checked my mirrors for any sign that I was being followed. There was none.

Castlederg Police Station was protected by a checkpoint and mechanical gates. Spiked metal ramps prevented car bombers getting too close, high walls, barbed wire and weld mesh prevented any direct assault and reduced the risk of mortar attacks.

The constable on guard duty was polite but firm and took the precaution of telephoning to confirm my appointment and identity before allowing me entry. I always wore a hat when leaving and entering police and army premises, you never knew who was watching.

Identification formalities over, I eased the Rover through the gates and parked outside the canteen. Painted in large white letters on the wall behind the only available bay were the words ‘Chief Supt’. I pulled into it and turned off the engine. As I tucked the Beretta beneath the driver’s seat, I reached into my jacket pocket, paused for a moment and then cursed. I’d forgotten to bring a spare magazine. It was a careless mistake and, no doubt, one that the quartermaster would rib me about on my return.

Eight o’clock is always a good time to get breakfast in a police canteen. The frying pans are hot and un-christened as the early shift doesn’t start arriving until nine. You always get a full selection from the menu and a friendly reception from the canteen cooks, who have time to rustle up ‘something special’. I ordered my usual – poached eggs, fried bread, bacon, mushrooms and tomatoes. Amongst my many weaknesses, a cooked breakfast is a big one. I washed it down with a good strong brew, took a trip to the lav, had a browse through the Belfast Telegraph, and then had a quick read through my report on the previous week’s contact.

It was exactly nine o’clock when I walked into the assistant chief constable’s reception office.

‘Prompt, as usual, Captain.’ The secretary smiled warmly from behind her typewriter. ‘Go straight in, they’re just having coffee.’

Chapter 5

I didn’t appreciate it as I walked in to join the waiting police officers, but Assistant Chief Constable Kieran O’Keefe was a worried man. The reasons were about to be made clear to me.

The seating was arranged in a circle. I sat myself down in the only empty seat, a soft leather armchair.

O’Keefe made the introductions. All the attendees were either senior policemen or heads of police units. I was introduced as ‘Captain X’. That made me smile. It was standard practice to give Special Forces soldiers a cipher or codename, but this one evoked childhood memories of Captain Kirk and Star Trek. I sensed a degree of discomfort in the room when my real name wasn’t provided. Not everyone agreed with soldiers being allowed such a concession.

Behind me, someone closed the heavy double doors.

‘Gentlemen,’ O’Keefe began, ‘I have asked the Captain to come here today in order to apprise us of the problems facing officers in armed contact with the provisional IRA and to advise us on best practice.’

O’Keefe had a nice turn of phrase. I was actually there to talk about killing terrorists. The previous week, I had led an observation on an unattended arms cache when a known member of the Provisionals had arrived at the scene and started to dig it up. The Provo, a lad called Masterson, had ended up dead.

O’Keefe looked towards me as he suggested that I might answer questions about the shooting. I nodded in agreement. I had nothing to hide; we had acted within the rules of engagement and Masterson’s weapon had been recovered.

As O’Keefe drew his introduction to a close, he mentioned there had been a lot of reports in the press about contacts between the security forces and the terrorist factions that were resulting in fatalities. Journalists were starting to claim that both the police and the army were operating a shoot-to-kill policy.

I’d heard the rumours and read the articles. But I was also aware that the official line was to treat the idea as ludicrous. The army is a small world. If something as serious as a shoot-to-kill strategy was in place, we would have heard about it. There had been nothing. Which meant I was possibly the first Special Forces officer to be involved in a discussion on the subject. It was certainly the first time I had heard any RUC senior officer use the term ‘shoot-to-kill’.

It looked like the agenda for the meeting had changed.

O’Keefe ended his opening speech with the announcement that he had appointed one of his best detectives to lead a small team that would be looking into all fatalities involving contact with the police or army. He also informed the meeting that an outside investigation officer was likely to be appointed soon. Favourite for the job was the deputy chief constable from Liverpool.

For several moments, I stared into space. I needed to think. I’d prepared myself for a discussion about the new terrorist cell I had heard about, not to give a detailed explanation of the methods my team were using to identify and take on the terrorists.

Aware that my body had stiffened and my sense of annoyance might show, I did my utmost to appear relaxed. I looked around at the others present. I only recognised one man: Detective Superintendent Dan Connell. Everyone knew Connell, if not personally then by reputation. He was old school, one of the RUC’s best investigators.

One thing struck me. On entering the room, I had been surprised I was the only military. I would have expected to have seen some spooks from the intelligence corps. But there were none. And now I was starting to realise why. This was an investigation and I was the suspect.

Connell led the conversation. I sat forward in my chair. From the looks the group gave me, I could see that I had their attention. I did my best to describe in detail how my small, four-man patrol had flown in to observe the arms dump that had been discovered accidentally by an RUC patrol. I avoided ‘army speak’ to avoid confusing them. If there is one thing soldiers are guilty of it’s talking in our own stilted language. Some police officers understood the lingo, most didn’t. So, I kept it simple. A cache of weapons had been left undisturbed in a dustbin buried underground in the middle of a deserted farmyard. Our team had been briefed to surround and observe the farmyard so that anyone arriving to collect something from the dustbin could be arrested.

I described how, after two days in position, the team’s patience had been rewarded: at two a.m. a lone male had entered the yard and started digging up the dustbin. The man had been challenged. When he responded to this by drawing a weapon from his pocket, he had been shot dead. I spared them a description of the injuries an MP5 had caused to the unfortunate boy’s face.

The subsequent question-and-answer session lasted for about half an hour. Several times I had to go over points I had already explained. My suspicion was right – this was definitely more cross-examination than de-brief. Connell, in particular, asked a lot of questions about the pre-op briefing and instructions given to soldiers in the event of contact.

In those days, I had little experience of interview technique. But I knew that most of the policemen, particularly someone like Connell, who had worked his way up through the ranks, knew how to tell the difference between a story and an account. They would be examining any repeated words or descriptions to see whether I, the ‘suspect’, was padding out a story to make it believable, or if I was describing the truth. I guess they figured I was kosher.

At last, we moved on to discuss the reason why I had attended the meeting in the first place. There was a threat from a new IRA cell that was operating in the area. Connell gave us a run-down.

The main suspects were brothers – Michael and Richard Webb. They were very junior members of the Provisionals. Until recently the Webb boys had run messages, carried ammunition and guns, and assisted members of the active service units by keeping watch. However, intelligence sources reported that they had now both been blooded.

Richard, at seventeen, was the eldest by two years. His olive skin and dark hair gave him a Greek appearance and so he’d become known as ‘Dick the Spic’. He had been christened as a sniper. An experienced IRA gunman had allowed him to fire an old Lee Enfield at an RUC patrol from the roof of a tower block. Richard missed and had almost been caught by the pursuing patrol.

Michael, still only fifteen, had planted a small bomb in a Protestant pub. He had telephoned a warning but had forgotten to use a code word and in the half-hearted moves to evacuate the pub, the barman had been killed.

Apparently, the two boys now considered themselves to be old hands.

Connell handed around a set of photographs for us to look at. I hadn’t seen either of the boys before. I did, however, recognise one of the people with whom he was pictured.

‘John Boyle,’ I said.

‘That’s right, Captain,’ replied O’Keefe. ‘We think that Boyle may be using the two boys to plan an attack.’

‘Do we have any idea of the target?’ I asked.

Connell paused and closed his eyes for a moment. ‘We believe the target is … the Assistant Chief Constable.’

We all remained silent.

O’Keefe was rigid and showed no emotion as Connell continued with his report. It was a frightening prospect, knowing that you were a specific target. Every RUC officer took precautions, general checks and methods to minimise the risk, but to be made aware that you had been singled out upped the ante considerably.

A report from Special Branch judged the threat from Boyle and his team to be ‘moderate’. That told me little. I guessed it meant that the risk was real but not imminent.

We talked at length about the threat, precautions O’Keefe could take and ways in which the threat might be countered.

Just before the meeting closed, O’Keefe fixed me with a cold stare. ‘What are your thoughts on these new lads, Captain?’ he asked.

‘Do you want a soldier’s view or one that is more acceptable, sir,’ I replied.

‘Just say what you’re thinking.’

‘Ok, I will. You know as well as I do that Special Branch can tell us who these guys are, where they live, where they drink, and the touts will even tell us other stuff about them. But you want them stopped, I guess.’

‘We want all forms of terrorism stopped, Captain. Not just this particular team.’

‘I understand that, sir, believe me. What I’m trying to say is that you operate from a perspective that treats these men as criminals.’ I could see from the attentive stares of those present that I had their attention.

‘Do go on,’ said O’Keefe.

‘With respect, sir. I’m a soldier and I think and act like one. People like me have been brought here to put fear back into the minds of the Provos.’

‘And how would you propose we should do that?’

‘Make it clear to them that if they target coppers they pay with their lives.’

‘Are you saying what I think you’re saying? That we should actually operate a shoot-to-kill policy?’

‘I’m saying we treat them like enemy soldiers and not like civilian criminals. If they pick up the gun and try to kill us, they know that the fight they are getting into is likely to leave them dead. Make them afraid.’

‘Like they fear the SAS, you mean?’

‘I mean so they understand that if they target us, we will come after them.’

O’Connell coughed. It was a timely intervention, interrupting what was turning into a political debate.

It was now ten o’clock. O’Keefe called time on the meeting.

I was the first to leave. As I walked through the ACC’s reception, the secretary was at her desk. I gave her a wink; she smiled in reply.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

‘Samantha.’ Nice name, I thought. Reminded me of a pretty little kid that was at school with my younger brother.

‘Be seeing you soon, Samantha.’

‘I hope so.’ The voice was warm, the smile broad. Different time, different place I’d be in there, I thought.

Another one of my weaknesses. But, well, I was younger then.

I wandered back to the Rover, recovered my pistol from beneath the driver seat and slipped it into my shoulder holster. The V8 engine roared into life at the first turn of the key and I headed off for base.

After seeing the dickers in the Cortina, I had already decided to play it safe and take a different route back to base. There was a detour along the eastern route out of Castlederg. It turned south and then drove parallel to the road by which I had arrived. I kept my hat on until I was away from the built-up area. The country lanes were normally deserted.

Held up for a short while by a slow-moving tractor, I had to accelerate to make up time. I was doing fifty on a single-track lane when a sudden movement in my rear-view mirror caught my eye. A blue Cortina was fifty yards behind and gaining fast.

The hairs on my neck stood up again. It was definitely the car I’d seen earlier. But this time there were four occupants.

My heart started to pound as the adrenaline pumped into my blood stream. It was time to be away. I hit the accelerator hard.

The road straightened out. The Cortina had now caught up and was again about fifty yards behind. In my mirror I could see the front-seat passenger leaning out of the window holding an AK47.

I immediately reached under the dash and activated the emergency locater beacon. Within seconds an alarm would be raised at GCHQ satellite monitoring. A back-up team would be on their way to me in minutes. That wasn’t going to help me now, though. However quickly they scrambled, the helicopter could not fly fast enough to make a difference. The Starship Enterprise was what I needed.

The rear screen of the Rover smashed as rounds from the AK47 punched through it. Instinctively I ducked.

I was going to have to fight for my life, and do it alone.

Chapter 6

As the glass from the broken window sprayed around me, I hit the gas.

The gearbox of the Rover kicked down, the powerful engine quickly putting space between me and the gunmen. I must have been doing eighty. It was too fast. The lane was narrow, high verges and thick hedges. If I met another tractor around the next bend I wouldn’t need to worry about my pursuers.

I searched my mind for an idea of what to do. I was a soldier and, supposedly, a trained driver. This should be a simple choice: run or fight. Adrenaline was preparing my body but clouding my thoughts; I tried to order them: if I crashed the terrorists would have me cold. So that was it, running wasn’t an option. I eased off the speed. There was nothing for it: I would have to meet them. But it would be on my terms. A plan began to take shape in my mind. I had to have an edge over them. What I needed was a nice blind bend.

I guess I was maybe a hundred yards in front when I found one. There were high trees on both sides with steep banks in front of them. If I stopped, the Cortina driver wouldn’t be able to get past me.

As I rounded the turn, I hit the brakes hard then yanked up the handbrake and swerved. The Rover slewed across the lane with the driver’s door facing away from the oncoming Cortina.

‘Thank fuck,’ I said out loud. It was the first time I’d completed the manoeuvre successfully.

With the road now blocked, I rolled out of the Rover and onto the road as fast as I could. Raw fear either motivates or immobilises. Luckily for me, it was the former. I was moving fast and my repeated exercises on the ranges were paying off. In a fraction of a second the Beretta was out of its shoulder holster and I was crouched behind the engine block, ready. Ready? By Christ, my hand was shaking even more than my heart was pounding.

The Cortina screeched around the bend and locked up.

I’d already decided the front-seat passenger with the AK47 was my greatest threat. As the Cortina skidded to a halt it presented me with a clear target by throwing him against the windscreen.

I aimed as best I could, firing six rounds. The windscreen exploded in a shower of glass. There were screams of pain and the sound of a male voice shouting.

The assault rifle skidded across the tarmac towards the Rover. My ears began to ring and the smell of cordite entered my nostrils. My senses felt alive, alert, excited. It was the first time I had aimed a pistol at an enemy, the first time I had taken on a live target.

I fired another three rounds, this time through the driver’s side of the now broken windscreen. I saw the outline of a body jerk back as the bullets struck home. Two more men appeared from the back seat, both of them small. The one on the driver’s side rolled out onto the bank; he had another AK47 in his hands.

Nine rounds fired, I thought; that left six in the magazine. Five for the last two gunmen and one for me. Either that or I took off for the hills. I wasn’t about to be taken prisoner.

I heard the sound of a drum beating loud in my ears. Then, I realised what it was. I could actually hear the rapid beating of my heart as the blood pumped through my veins. All my earlier apprehension and fear had gone, replaced by excitement, survival instinct, blood lust, I’m not sure exactly what; but I was now into the combat. And I’m not ashamed to say that I loved it. To fight and win is what every soldier trains for and I was doing just that.

I’d lost sight of the two surviving gunmen. Realising they must be behind their car, I quickly crawled around the front of the Rover. The familiar staccato crack of an AK47 broke the silence as the remaining windows of the Rover exploded. I had to take out that AK, and fast.

A barrel appeared above the rear of the Cortina. I crouched and fired over the bonnet of my car, using the strength and solidity of the engine for protection.

I put three more bullets through the rear of the terrorist car and then held my fire. There was nothing solid to block the 9mm rounds, they would have passed straight through the thin metal and plastic. Everything became quiet.

Three rounds left. Nearly time to run.

From behind the Cortina, a small man stood up. He looked very young, no more than a teenager.

The moment I saw his face, I knew him. Not half an hour before, I had been looking at his picture. It was Richard Webb, one of the new local IRA cell.

He raised his hands. They were red, bright red. He was either badly wounded or covered in blood from one of the others.

‘I surrender,’ he screamed at me. ‘I give up. Don’t shoot, don’t shoot.’

I should have shot the kid there and then. Most of the guys in my troop would have done. In the heat of battle there was no way to judge how dangerous this apparently unarmed boy actually was. Most of my nightmares since have ended with him pulling a hidden gun and shooting me.

But for some stupid reason, I held my fire and called out to him. ‘Where’s the other one, where’s your mate?’

Silence.

Webb walked slowly forward, his hands high in the air. He looked like a very scared child.

I shouted again. ‘Lie down on the ground.’

He stood still. I could see he was that petrified, he couldn’t do anything. Where the hell was that other one, I thought.

The lull was broken by wild rifle shots. The fourth terrorist limped around the front of the Cortina firing the AK47 from his waist, his leg bleeding profusely as he launched a desperate last charge.

This time, I was more controlled. I fired just twice, it was all I could risk. The first round missed. I held my breath, gripped the Beretta tight and prayed. The second round struck home, middle of the chest. He dropped like a stone.

But as he did, one of the bullets from the AK ricocheted under the floor of the Rover and hit my left boot. The force spun me around and dumped me on my back.

As I fell, I caught sight of Webb running away.

I was now exposed. I had one round left. That would be for me if the attack wasn’t over.

I waited. The pain in my foot was manageable but, as I tried to stand, I soon realised that I was going nowhere. It felt like the bullet had gone straight through my heel.

For the next fifteen minutes I hobbled and then crawled to the edge of an adjacent copse. As the anaesthetic effect of adrenaline lessened, the pain increased.

I soon started to run out of energy. Locating a large tree, I sat down with my back to the gnarled trunk.

I checked my boot. There were two small and jagged holes near the heel where it looked like a fragment of the AK47 round had gone straight through. Although the pain was intense and I was losing blood, I breathed a sigh of relief. A direct hit could easily have taken my foot off.

As I sat back to wait, I considered my options. I needed to stay close to the Rover to ensure that the rescue team could find me, but I also faced the possibility of young Richard Webb returning with some mates. He would have seen me go to ground and would know that I was hit.

I decided to give it twenty minutes. After that time, if no help had arrived I would make myself scarce.

My heart rate slowed as my breathing returned to normal. In the distance I could hear a metallic clicking as the engine of one of the abandoned cars cooled down.

I checked the Beretta. There was a round in the chamber and, just as I had expected, the magazine was empty. I had counted right. One left for me.

Behind me, several birds in the copse burst into song. I figured that they must have been silenced by the recent gunfire and that now, realising that the commotion had subsided, they considered it safe enough to resume their normal behaviour.

In the tree above me, a wood pigeon cooed. It was a good sign. I had a look-out, a pair of eyes with a view that would be scanning the local field for any sign of approaching danger.

A faint throbbing noise reached my ears. I checked the sky and listened. The familiar thud of a helicopter rota grew slowly louder. I allowed myself a smile. Help was on its way.

The rescue team helicopter soon hovered over the lane. I dropped the Beretta into its holster, raised my arms above my head and hobbled out to greet them. My pigeon sentry took off across the field, his personal safety now far more important than looking out for me.

With the helicopter above me and with the effect of adrenaline starting to wear off, I lay down on the grass.

A few moments later, I winced as a medic began cutting my boot off.

‘The bullet’s gone straight through, missed the bone by the look of it,’ he said, cheerfully.

A Parachute Regiment Sergeant loomed over me, the pistol in his right hand pointed at my head. ‘Who are you, mate?’ he demanded.

I explained.

‘Well, with respect, boss, you’ve made a right mess here. You on your own?’

‘Fraid so.’

‘Well you slotted all three. You done well, you done bleedin’ well. Give us a few minutes and we’ll have you loaded up and out of here.’

My body sagged as the morphine syrette the medic had pushed into my thigh took effect. Lying there in the dirt, soaked in sweat with the smell of cordite and blood in my nostrils, the prospect of a bath and a warm bed seemed like paradise. And there was always that secretary.

A few days later, as I limped into the squadron debrief, I gracefully accepted the ribbing I was due on account of forgetting to take a spare magazine.

But my decision to use a Beretta was vindicated. With a smaller magazine, the Browning would not have had the firepower to get me out of the jam. The Beretta did.

From that day until the day I left the army, that pistol never left my side.

The threatened attack on ACC O’Keefe never materialised. He was kind enough to send me a personal ‘thank you’ note in which he accepted that when it came to putting fear in the minds of the terrorists, I may well have made my point.

And Richard Webb? The RUC picked him up less than a day after the attack. Sick and still shaking, he was caught hiding in a cow shed.

Chapter 7

The SAS Regiment were used to having soldiers around recovering from one kind of injury or another. The medical staff rated me P3: temporarily unfit for military duty.

I took a lot of stick from the lads in the squadron. Having a bullet wound in the foot led to the predictable accusations that I’d done it myself. For the next couple of months, even the slightest error or mistake was inevitably met with ‘shot yourself in the foot there, boss’, or something similar.

Take a look at any branch of the army, and you will find plenty of admin tasks and a distinct shortage of people volunteering to do them. Officers and soldiers on ‘light duties’ are perfect for these jobs, so, as soon as I was well enough, I found that my daily commute was from the Officers Mess to HQ Company Administration Office. To get around the camp, I tied my crutches to the side of an old Dawes bicycle and then pedalled with my good leg.

It wasn’t long before I became bored. Watching other people training, trying out new equipment or heading off to a deployment or exercise wasn’t my idea of fun. So when an invitation arrived on the adjutant’s desk for a volunteer to join a training course with the Metropolitan Police, I was the first to put my name down.

Two weeks later, I joined nearly twenty police detectives from various parts of the UK on a National Hostage Negotiators’ Course.

The hostage programme was euphemistically known to us students as the ‘Hello, my name is Dave and I’m here to help’ course, on account of the standard opening that we were required to employ when initiating dialogue with a hostage taker. It was a good course: I learned a lot, including how to take different approaches to terrorists, criminals and the mentally disturbed – the mad, bad and sad, as we termed them. It even included advice on handling individuals who were threatening to throw themselves off bridges or high buildings.

The reason for the SAS being offered a place on the programme was clear. If the wheel came off and a terrorist hostage incident took place, we would be called. Three weeks after the course ended and I had returned to Hereford, that exact scenario occurred.

At 11.30 am on 30th April 1980, a man called Salim Towfigh was at the front of a small group as they approached 16, Prince’s Gate, London: the Iranian Embassy. Salim was surprised to find that the police officer who normally stood outside the embassy was not at his post.

As the small group of terrorists burst in through the front door, they found the PC inside, enjoying a short break and a cup of tea. They fired an automatic pistol into the roof of the reception area.

The Iranian Embassy siege had begun.

Chapter 8

I was sat drinking tea in the Kremlin when the telephone rang.

The Kremlin I’m referring to wasn’t the seat of power of the Russian government, more a rather untidy and dilapidated military building that served as the planning and intelligence base for HQ Company. After the welcome interlude provided by the hostage course, I had returned to my admin role. Like most large organisations, the army has an insatiable appetite for paperwork. My less-than-challenging job was to make sure that the beast didn’t go hungry.

For nearly thirty seconds, the phone kept ringing. A corporal from the Army Ordnance Corps who was supposed to deal with calls was away from his desk making a brew for the CO and one of the squadron commanders, so finally I picked up the receiver.

‘Who’s that?’ said a gruff male voice.

‘Perhaps I should be asking the same question?’ I said.

‘Get me someone from the headshed,’ the voice demanded.

Whoever the caller was, he seemed to be familiar with our local terminology. I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt and not hang up the phone. ‘Who’s calling?’ I asked.

‘Colin … is that you? Now stop fuckin’ about and put an officer on. It’s Reg Toms, here. I used to be on A squadron.’

Colin was the name of the clerk who was making tea. I was convinced.

‘You’re speaking to an officer, Reg,’ I replied. ‘What can we do for you?’

‘Uh … OK, boss.’ Reg Tom’s voice took a different tone. ‘Well, it’s not what you can do for me. It’s what I can do for you. Find a television and turn it on. I’m a copper in the Met now. The shit’s hit the fan down here, big time. The Iranian Embassy has been taken over by terrorists.’

It took a moment for the words to sink in.

As Reg continued, I waved frantically to Colin to get him to hand me a pen and paper so I could jot down what Reg was telling me: The police in London had responded to a hold-up alarm at the embassy after being unable to raise the PC posted to guard the building. They had arrived at Prince’s Gate to find the PC and a number of staff had been taken hostage.

Reg reckoned it was only a question of time before we got the call. My squadron had just taken over our stint on CRW, the Counter Revolutionary Warfare team. If the Met did ask for help, we would be it.

Colin barged in on the ‘Headshed’ meeting. A few seconds later, he emerged from the CO’s office with instructions to initiate the CRW call-out.

I kept Reg on the line as Tom Crayston, the B-squadron Commander, appeared behind Colin. He looked at me, apologetically. I knew what that meant. Someone was going to have to stay behind, to monitor phone calls, to organise movement of men and equipment … to do the paperwork. With an injury that prevented me from being any use at the sharp end, I was the obvious choice.

‘Sorry, Finlay,’ said Tom.

I shrugged. Although I’d now ditched my crutch in favour of a stout walking stick, I knew I was still something of a passenger.

‘Boss is on the phone to the Met now,’ Tom continued. ‘We’ll take one of the Range Rovers to London.’

‘We’re not waiting to be called out?’ I asked.

‘No. Boss wants two teams of twenty-five. If we can’t get enough people together from B squadron then make up the numbers from anyone qualified who can get here within the hour. I’ll call you with as much as I know while we’re in transit. Get the kit loaded and have everyone on the road by 1400 hours. Clear?’

I nodded.

Some of the lads were in the ‘killing house’ going through drills and practising their skills; others were preparing to leave for an exercise. Many were off base: on-call but off-duty. Colin bleeped them.

I made a few friends that day. As Tom had predicted, Colin struggled to locate the numbers that the CO had ordered to be called in. With all the overseas deployments, the initial ‘live-op’ transmission via the squadron pagers didn’t produce enough men to create two teams. I called in some lads from A and D squadrons to make up the numbers. To my surprise, a few treated the calls I made with some cynicism, believing it to be ‘just another exercise’. They changed their tune on learning it was a live operation.

All through the day we kept the televisions on and the radios tuned in to London channels.

Tom Crayston telephoned with sufficient information to enable me to do an initial briefing in the camp hangar. After that, the lads were to load up and head to the Education Corps barracks at Beaconsfield, just outside London. The regimental Sergeant Major created the two teams, red and blue, and allocated men to them.

The two p.m. target for departure soon slipped, but, by six that evening, once we’d obtained the right governmental approvals and prepared fifty men with what they needed, the Range Rovers and transit vans were loaded with enough kit to start a small war.

I was kept so busy I didn’t have time to dwell on the sense of disappointment I was feeling. Like everyone else, I was champing at the bit to get involved in the kind of incident that seemed to be unfolding.

But at seven-thirty, just as the first Range Rover was about to head out through the gates to the camp, I had a stroke of luck. The hostage negotiator the Met had appointed to speak to the Arabs at the embassy turned out to be one of the instructors from the course I had just been on. He suggested to Tom Crayston that it would be a good idea to bring me along.

I had my boots on, my kit packed and my personal weapon booked out of the armoury within ten minutes of receiving the news from Colin that I was being ordered to join the convoy. I threw my kit into the back of the last remaining Range Rover and climbed into the front passenger seat. As I slid my walking stick beneath the seat and turned to the driver, I almost laughed. Driving the car was the very same soldier that had handed me a sweetened tea at the end of the Fan Dance exercise during selection.

‘Scraped inside the time again eh, boss?’ he said, grinning from ear to ear.