6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Open Book Publishers

- Sprache: Englisch

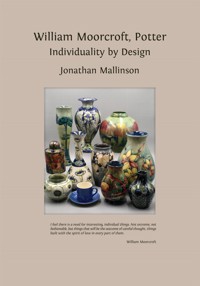

William Moorcroft (1872-1945) was one of the most celebrated potters of the early twentieth century. His career extended from the Arts and Crafts movement of the late Victorian age to the Austerity aesthetics of the Second World War. Rejecting mass production and patronised by Royalty, Moorcroft’s work was a synthesis of studio and factory, art and industry. He considered it his vocation to create an everyday art, both functional and decorative, affordable by more than a privileged few: ‘If only the people in the world would concentrate upon making all things beautiful, and if all people concentrated on developing the arts of Peace, what a world it might be,’ he wrote in a letter to his daughter in 1930.

'William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design' is a pioneering study by Jonathan Mallinson, Emeritus Fellow of Trinity College, Oxford. It follows the career of William Moorcroft through a wealth of private papers, letters and diaries, business correspondence and published reviews in newspapers, trade magazines and art journals. Richly illustrated with examples of his pottery, it explores what lay behind the unique impact of work sought by museums and treasured in homes the world over. The book examines an artist’s very individual response to the turbulent half century in which he worked. It will appeal to both specialists and general readers with an interest in pottery, the decorative arts, and the cultural history of the times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

WILLIAM MOORCROFT, POTTER

William Moorcroft, Potter

Individuality by Design

Jonathan Mallinson

https://www.openbookpublishers.com

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson

This work is licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text for non-commercial purposes of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information:

Jonathan Mallinson, William Moorcroft, Potter: Individuality by Design. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2023, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0349

Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. This information is provided in the captions and in the list of illustrations. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.

Further details about CC BY-NC licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web

Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0349#resources

ISBN Paperback: 978-1-80511-053-8

ISBN Hardback: 978-1-80511-054-5

ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-80511-055-2

ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-80511-056-9

ISBN XML: 978-1-80511-058-3

ISBN HTML: 978-1-80511-059-0

DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0349

Cover image: Margaret Mallinson. Cover design: Jeevanjot Kaur Nagpal

For Beatrice Moorcroft

Table of Contents

Abbreviations x

Acknowledgements xii

Introduction: William Moorcroft, Potter 1

PART I: MAKING A NAME 7

1. 1897–1900: The Making of a Potter 9

2. 1901–04: The End of the Beginning 31

3. 1905–09: Experiment and Adversity 51

4. 1910–12: Approaching a Crossroads 71

5. 1912–13: Breaking with Macintyre’s 93

PART II: CREATING A STUDIO 115

6. 1913–14: A New Beginning 117

7. 1914–18: The Art of Survival 137

8. 1919–23: A Lone Furrow 163

9. 1924–25: Recognition of the Artist Potter 185

10. 1926–28: Re-negotiating the Future 207

PART III: EXPRESSING A VISION 231

11. 1929–31: No Ordinary Potter 233

12. 1932–35: Individuality and Industrial Art 259

13. 1936–39: Pottery for a Troubled World 291

14. 1939–45: Adversity and Resolution 327

Conclusion: Individuality by Design 357

Bibliography 369

List of Figures 381

Index 389

Additional resources including images of pottery and original documents are available online at: https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0349#resources

Abbreviations

AJ The Art Journal

BIF British Industries Fair

BIIA British Institute of Industrial Art

BPMF British Pottery Manufacturers’ Federation

CAI Council for Art and Industry

DIA Design and Industries Association

DOT Department of Overseas Trade

PG The Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review

PGR The Pottery and Glass Record

RFR A Roger Fry Reader (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996)

V&A Victoria & Albert Museum

WM Archive William Moorcroft, Personal and Commercial Papers, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD1837

Acknowledgements

It is a great pleasure to thank the following who have in many different ways assisted me in this project: Gaye Blake-Roberts (Curator, Wedgwood Museum), Olivier Cariguel, Dr. Wilhelm Füßl (Archive Director, Deutsches Museum), Jane Harrison (Documentation Manager, Royal Institution of Great Britain), Rob Higgins, Kate Reed, Nicholas Smith (Archivist, V&A Archive), Matthew Winterbottom (Curator of Western Art Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Ashmolean Museum) for swift and informative responses to specific questions; staff at the Bodleian Library, and the National Art Library, who helped me navigate their extensive holdings of trade and art journals; and Julian Stair, whose comprehensive bibliography in his unpublished PhD thesis ‘Critical Writing on English Studio Pottery 1910–1940’ was an invaluable resource for exploring parallels with the reception of Moorcroft’s pottery. I am indebted to the late John Moorcroft, who kindly lent me documents relating to his father’s time as a designer at J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd., and to Maureen Leese for allowing me to consult her copy of Harry Barnard’s unpublished memoir. I am grateful to Paul Atterbury, whose own writings on Moorcroft were an early inspiration for this project, and whose subsequent comments encouraged me to finish it. And I have greatly appreciated the interest shown in this book by former students and colleagues (not least María del Pilar Blanco), which confirmed my belief that the significance of William Moorcroft’s career deserves to be more clearly established, and his work more fully appreciated.

To understand William Moorcroft the potter, it is necessary to see a lot of his pottery. His work is represented in museum collections around the UK, and the holdings of the Cannon Hall Museum, the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Moorcroft Museum, the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, and the V&A provide a good range of examples. No less helpful has been the opportunity to discover (and at times examine) objects via the online archives, catalogues or sales previews of auction houses the world over, and I am particularly grateful to those who have willingly responded to requests for further details or photographs of individual pieces: Fiona Baker, Hayley Dawson, Michael Jeffery, Bill Kime, George Kingham, James Lees, Jo Lloyd, John Mackie, Gemma Sanders. I offer my sincerest thanks, too, to many collectors, dealers and experts in the decorative arts for their encouragement and support, and their invaluable assistance in locating examples of Moorcroft’s work to illustrate this book: Jeremy Astfalck, Michael Bruce, Alison Davey, Steve Doherty, Stephen Elliott, Wayne Hopton, Lorraine Leightell, Andrew Muir.

Of indispensable value has been the contribution of John Donovan, who over many years showed us countless outstanding examples of William Moorcroft’s pottery, and generously shared his knowledge, experience and appreciation of his art. Our frequent discussions helped me to make sense of the qualities so often identified in contemporary reviews of Moorcroft’s work, and have been a constant source of inspiration.

It is self-evidently true that without the energy and vision of Richard Dennis the work of many British artist potters would still be largely unknown. His landmark exhibition of William Moorcroft’s pottery at the Fine Art Society in 1973, and the catalogue (with its introduction by Paul Atterbury), rekindled interest in a potter whose work had been lost from view in the decades following his death. The pioneering book which followed (with additional commentary by Atterbury) illustrated the extraordinary range of his output, and put this pottery permanently on the map. I, like many others, have benefited greatly from this work, but I owe as much to the man as to the book. From his first positive response to a speculative email asking if he would be willing to discuss my early thoughts on Moorcroft’s pottery, through many visits to his home where he and Sally Tuffin were so warmly welcoming, he has given unfailing encouragement as this project has progressed; I thank him for his sensitivity and open-mindedness, and for much else besides.

I am indebted, too, to Walter Moorcroft’s four daughters—Jean Potter, Sheila Moorcroft, Sara Morrissey, and Lise B. Moorcroft, who, midway through this project, gave me permission to work on an extensive archive of family papers covering the whole of William Moorcroft’s career, and who, since that time, have been constant in their support. Without their generosity and trust, this book would have focussed simply on the pottery and its public reception in Moorcroft’s lifetime; the evidence of the archive has added countless insights into the potter and the man. This invaluable resource has since been deposited in the Stoke City Archives, under the filename ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, where its survival is assured for future generations.

If members of the Moorcroft family were for many years the custodians of this archive, its very existence is due to William’s daughter, Beatrice, who gathered together in the early 1980s material accumulated during her father’s career, from his earliest years as designer for J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd. to the end of his life: extensive correspondence and other documents relating to the two major institutional relationships in his life; countless letters written to him from friends, family, retailers, suppliers, owners of his work; diaries and notebooks, drafts and jottings relating to his activity and vocation as a potter. Without her foresight, these extensive primary sources might easily have been lost. It was her ambition to write a book about her father, not a memoir—neither she (nor her brother) had direct knowledge of the first thirty years of her father’s career, and she understood the hazards of reminiscence—but a history based on documentary evidence and her own additional research. Her book was never written, but her prescient collection of all this material made possible the writing of this one. To her, the debt is incalculable.

In 1934, Moorcroft confided to the publisher F. Lewis his hope that a book entitled ‘William Moorcroft—Potter’ might ‘someday’ be published, to which Lewis responded enthusiastically: ‘I am definitely interested as this seems a book which […] should go well.’ I am immensely grateful to Open Book Publishers for picking up where F. Lewis left off nearly ninety years before, and for their faith in this book and its author. From my very first approach, Alessandra Tosi has been wholly supportive of the project, and at every stage of the publication process she and her team have worked with quite exceptional efficiency, sensitivity and collaborative spirit. Her own suggestions have led to countless improvements, and I have benefited greatly from the expertise of Jeevan Nagpal, Alex Carabine, Melissa Purkiss, and Laura Rodríguez. OBP are the perfect vehicle for this book, and their guiding principles are in complete sympathy with William Moorcroft’s own. In their commitment to the dissemination of knowledge as freely and widely as possible, they enact his ambition to bring within the reach of many the beauty of his pottery, and they echo his belief that business is as much about service as it is about financial gain. I am most grateful to Caroline Warman, whose own publications first introduced me to OBP, and whose almost instantaneous (and unconditionally positive) reply to my enquiry about their possible interest was the final defining moment in this project.

It is no mere trope of Acknowledgements to say that this book owes its very existence to these particular contributions; to benefit from one may be regarded as good fortune, to benefit from all looks like destiny. I owe a debt of gratitude beyond words, however, to my wife, Margaret, co-excavator, fellow note-taker, and first reader of every draft of every chapter, my companion on every journey of discovery, my consultant and confidant. This project has been a dream shared from the outset; it could not have been realised alone.

Introduction: William Moorcroft, Potter

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.16

William Moorcroft (1872–1945) was one of the most celebrated potters of the early twentieth century. His work was admired by collectors and connoisseurs of ceramics, exhibited in museums, reviewed in leading art journals, and awarded the highest honours at World’s Fairs over a period of more than thirty years. His decorative and functional wares were stocked by some of the most prestigious retail outlets in the world, from Thomas Goode & Co. in London to Eaton’s in Toronto, from Tiffany in New York to Rouard’s gallery A la Paix in Paris, and his long collaboration with Liberty’s was an unprecedented and highly creative association of innovative designer and progressive retailer. His earliest work, launched under the title Florian Ware, was rated a ‘chemical and artistic triumph’,1 and forty years later examples of his tableware would be singled out as models of ‘undatedly perfect’ design.2 He was one of only a handful of potters at the time to hold a Royal Warrant, and at his death he was said to be the equal of any potter since Josiah Wedgwood.3 In a career which extended from the final years of the Victorian age to the end of the Second World War, a period of political upheavals, economic crises and conflicting aesthetics, artistic acclaim was matched by commercial success.

This was the achievement of a potter who worked simultaneously as artist, chemist and manufacturer. Moorcroft spent the first sixteen years of his working life as Manager of the Ornamental Pottery department at the forward-looking firm of James Macintyre & Co., Ltd., where he was responsible for the design and production of both functional and decorative wares. Under his control, this soon became one of the most renowned art potteries of its time. When Macintyre’s closed the department in 1913, Moorcroft (with financial support from Liberty’s) established his own pottery from where he continued to enhance his reputation as a ceramic artist, even in the challenging conditions of wartime and post-war Depression. In both these phases of his career, he designed form and ornament for all the wares produced; he created his own distinctive decorative technique, and developed a unique palette of underglaze colours; he oversaw the employment and training of his decorators; and he was responsible for the promotion and sale of his work. This combination of roles was without equivalent.

Moorcroft is most often classified among art potters, a category used to describe makers of largely decorative wares, active roughly between the years 1870 and 1920. It is a broad category, both chronologically and conceptually. It includes the craft studios of large firms such as Doulton, Minton or Wedgwood, independent factories such as Linthorpe or Della Robbia, and smaller enterprises focussed on the work of individual potters such as William de Morgan, Bernard Moore or William Howson Taylor. Art pottery covered a wide range of decorative styles, from the refined low-relief ornament of Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon’s pâte-sur-pâte studio at Minton, to the charming sgraffito scenes by Hannah Barlow at Doulton Lambeth; from the dramatic glaze effects of Howson Taylor at his Ruskin Pottery, to the stylized lustre designs of Pilkington’s Royal Lancastrian ware. But it was unified by its principal focus on decoration, be it that of an artist/decorator, or of a ceramic chemist; the vessel itself served implicitly as a canvas, some potters even decorating blanks supplied by other firms. It was also an essentially collaborative enterprise, its ‘authorship’ generally attributed to the firm which produced it. If individual names were associated with objects, it was most often the name of the decorator, artist or chemist, who might initial or otherwise identify their work.

In terms of organisation and aesthetic, Moorcroft clearly had much in common with the manufacturer of art pottery. Both his department at Macintyre’s and his own works at Burslem were characteristic of many industrial workshops, employing a team of throwers, turners, and decorators to assist in the making of the wares. And yet, for all that, Moorcroft’s practice differed in significant ways. Whereas the design of most art pottery was essentially collaborative, Moorcroft designed the complete object, form, ornament and colour together. And although he did not make the wares himself, he was at the centre of production in ways which had few parallels in art potteries: he drew the decoration template for each shape, he created the oxide mixtures for his colours, and, in the case of his flambé wares, he personally fired the kiln. This investment in his work would soon be noted. He was rapidly distinguished from the corporate identity of Macintyre’s and recognised as a name in his own right, and after 1913, when he was working for himself, his pottery was as often attributed to him as an individual as it was to the firm in whose name he operated. At the time of his death, he was even classified as a ‘studio potter’.4 This term was associated, from the 1920s particularly, with a quite different concept of pottery, its principal emphasis falling on the pot as a thrown vessel (rather than as a decorated one), the creation of a craftsman working alone and independently rather than the result of more collaborative enterprise. The designation did not imply that William Moorcroft fell squarely into that category, but it did suggest what distinguished him from the generality of art potters; Moorcroft did not simply decorate ceramic vessels, he expressed himself in clay.

What made Moorcroft stand out too, though, was not just the individuality of his art, but also his commercial success. Many highly regarded art potteries closed in the opening decades of the twentieth century, from Della Robbia (1906) and de Morgan (1907) to Howson Taylor (1935) and Pilkington (1938). Even at the end of the nineteenth century, the heavily subsidised output of Doulton’s Lambeth studio was described in an obituary of Henry Doulton as ‘one of the few sacrificial tributes of Commerce to Art’,5 and thirty years later the studio potter Reginald Wells would conclude (wearily): ‘do not imagine there is a living in so-called artistic pottery—there is not.’6 Throughout the 1920s, though, even as the country began to drift into a post-war depression, Moorcroft’s achievement was noted:

In Mr Moorcroft the present generation has an artist and a potter, who is practising successfully in commerce. The combination is remarkable, for it is one that is seldom met with.

7

The emphasis is significant; he was not regarded as a manufacturer in the business of making pottery, he was recognised as an artist potter whose work had wide appeal. And this corresponded exactly to how Moorcroft saw himself. In the face of constant changes in taste and market conditions, he remained true to his artistic principles, often speaking out against designs which merely followed the trend of the moment. In a letter to The Times at the end of the 1925 Paris Exhibition which introduced a new ‘modernity’ to industrial design, he affirmed that artistic integrity, not fashion, was the route to commercial success. ‘If we are to succeed in the markets of the world’, he wrote, ‘it will be mainly by being ourselves’.8 His survival, even in the depths of the Depression, would be evident vindication of that belief.

This success was due, too, to the range and quality of the wares he produced. Moorcroft was more than just an art potter, and his market was not simply a market of collectors; he produced pottery both functional and decorative, from modestly priced tableware to exhibition pieces which commanded prices comparable to those of the most celebrated studio potters. But all were produced by the same means, to the same standard, in a range of prices affordable by customers across a broad social spectrum; in Moorcroft, commercial astuteness and artistic integrity came together. As one critic noted in the 1920s, even a modest piece of Moorcroft’s pottery is ‘regarded by thousands of people as a priceless possession’.9 His functional wares were in competition with those produced by much larger, mass-producing factories, and successfully so. His Powder Blue tableware would be the most striking example of this, hailed as an icon of modern design more than twenty years after its creation, and which continued to sell well even when the quite different aesthetic of Clarice Cliff was dominating the market. It was a model of industrial design and commercial success, yet it was made, significantly, by hand; in this respect, too, Moorcroft’s work spanned the worlds of the manufacturer and the artist.

It was this fusion of roles which clearly distinguished Moorcroft from (and for) his contemporaries, but it has led, paradoxically, to his relative neglect today. Being neither an individual potter nor a designer for mass production, he inevitably falls outside the scope of critical studies both of craft pottery and of industrial design.10 He is included in one reference work on art pottery, but his pottery is examined in entries on J. Macintyre & Co. and W. Moorcroft Ltd., thereby implying corporate authorship of the pottery produced.11 In another study, his designs from the ‘Art Deco’ period are discussed under the name ‘Moorcroft’, in a section devoted to ‘Established Factories’.12 In only one book is his work considered under his own name.13

This perspective is significant, and it has informed other accounts of Moorcroft’s work. He has been situated in a group of artist potters ‘concerned about running an efficient pottery with a marketable, profitable product’,14 and has been attributed with the ambition to create a ‘successful international commercial art pottery business’.15 Moorcroft’s close personal involvement in the design and production of his pottery has been similarly evaluated from a perspective of business management. One study characterises him as an ‘autocrat’,16 and another, while conceding his accomplishments at the time, considers his organisational model ‘detrimental to the continued and future success of the business’.17 If his contemporaries saw him as ‘a manufacturer, but also an artist’,18 it is as a manufacturer that he is principally considered today. In consequence, his pottery is implicitly construed as a trading commodity, and his enduring achievement situated not in the works he made, but in the firm he established in 1913, and from which pottery continues to be produced.19 The name ‘Moorcroft’ has taken on a generic force, and William Moorcroft’s identity has been absorbed, paradoxically, by the Company which bears his name. One writer has referred to his pottery as ‘old Moorcroft’,20 while another has conflated the firm’s entire production into one single entity: ‘There is no such thing as ‘old Moorcroft’ or ‘new Moorcroft’, just Moorcroft.’21 It is an ironic fate for a potter who came to prominence through the force of his individuality.

This construction of a corporate identity is quite consistent with the model of many art potteries such as Della Robbia or Pilkington, whose designers often worked to a particular house style, or whose collaborative mode of production implied a more commercial product. Indeed for many, only pottery created by a single craftsman can have the personal expressiveness of an art object. But to see Moorcroft in this light is to make assumptions about his practice and priorities inconsistent with his reputation at the time, and which sit uncomfortably with his conception of pottery as a vehicle for self-expression. Self-evidently, his contemporaries could have had no conception of Moorcroft as the originator of a firm which would survive beyond his time; but nor did they consider him simply as a manufacturer. Even the British Pottery Manufacturers’ Federation (BPMF) would explicitly categorise him as an artist, recognising in him quite different priorities from theirs, and when, in an obituary, he was likened to Josiah Wedgwood, it was (clearly) not Wedgwood the business man who was evoked, but Wedgwood the potter:

By the death of William Moorcroft, the art of pottery has lost a truly great exponent. In his mastery of the craft, as potter, painter and chemist, he was probably the equal of any potter since the days of the first Josiah Wedgwood. All his work was strikingly original.

22

This book sets out to recover William Moorcroft. It is not the first chapter of a longer narrative, it is the story of a potter whose ambition was simply to be himself, individual by design, and whose success, artistic and commercial, would be founded on that.

1 A.V. Rose, ‘Florian Art Pottery’, China, Glass and Pottery Review, XIII:5 (December 1903), n.p.

2 N. Pevsner, ‘Pottery: design, manufacture and selling’, Trend in Design (Spring 1936), 9–19 (p.19).

3 ‘William Moorcroft’, Pottery and Glass Record [PGR] (October 1945), p.21.

4 Ibid.

5The Graphic (11 December 1897), quoted in D. Eyles, The Doulton Lambeth Wares (1975); rev. L. Irvine (Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis Publications, 2002), p.134.

6 R. Wells, ‘The Lure of Making Pottery’, The Arts and Crafts (May 1927), 10–13 (p.13).

7 ‘Pottery and Glass at the Paris Exhibition of Decorative Arts’, Pottery Gazette and Glass Trade Review[PG] (September 1925), p.1398.

8The Times (7 October 1925).

9PG (September 1925), p.1398.

10 He is not discussed in E. de Waal, 20th Century Ceramics (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), and there are just the briefest references in A. Casey, 20th Century Ceramic Designers in Britain (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2001), P. Todd, The Arts and Crafts Companion (New York: Bullfinch Press, 2004), and T. Harrod, The Crafts in Britain in the 20th Century (Yale: Yale University Press, 1999).

11 V. Bergesen, Encyclopaedia of British Art Pottery 1870–1920 (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1991).

12 P. Atterbury, ‘Moorcroft’: in A. Casey (ed), Art Deco Ceramics in Britain (Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), pp.74–78.

13 J.A. Bartlett, British Ceramic Art 1870–1940 (PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1993).

14 G. Clark, The Potter’s Art: A Complete History of Pottery in Britain (London: Phaidon, 1995), p.129.

15 R. Prescott-Walker, Collecting Moorcroft Pottery (London: Francis Joseph Publications, 2002), p.32.

16 P. Atterbury, Moorcroft: A Guide to Moorcroft Pottery, 1897–1993 (Shepton Beauchamp: R. Dennis & H. Edwards, 2008), p.32.

17 Prescott-Walker, op. cit., p.33.

18The New Witness (26 February 1914), p.540.

19 The story of Moorcroft’s firm after his death in 1945 has been told in different ways. In addition to the books of Atterbury and Prescott-Walker, see also Walter Moorcroft, Memories of Life and Living (Shepton Beauchamp: Richard Dennis Publications, 1999); N. Swindells, William Moorcroft: Behind the Glaze. His Life Story 1872–1945 (Burslem: WM Publications Ltd., 2013; and three books by H. Edwards (aka Fraser Street): Moorcroft: The Phoenix Years (Essex: WM publications, 1997); Moorcroft: Winds of Change (Essex: WM Publications, 2002); Moorcroft: A New Dawn (Essex: WM Publications, 2006).

20 Prescott-Walker, op. cit., p.38.

21 Swindells, p.193.

22PGR (October 1945), p.21.

PART I

MAKING A NAME

1. 1897–1900: The Making of a Potter

© 2023 Jonathan Mallinson, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0349.01

1. Background and Education

William Moorcroft was born in 1872. He was the son of a ceramic artist, Thomas Moorcroft, Chief Designer at E.J.D. Bodley’s, which was one of the leading potteries in Burslem. Years later, Moorcroft paid tribute to the formative influence of both his parents and to ‘their endeavour to surround their children with all things beautiful and elevating’.1 This childhood idyll, though, was short-lived. In May 1881, Moorcroft’s mother died, aged thirty-two, leaving his father to care for William and three brothers, two sisters having died in their infancy. Thomas employed a housekeeper, whom he married in 1884, but he himself died just nine months later, in 1885, aged thirty-six. Moorcroft was not quite thirteen.

If his parents had sown the seeds of artistic sensitivity, Moorcroft’s formal training helped them flourish. Burslem was at the centre of progressive art education in the Potteries. The Burslem School of Art, which had enjoyed a brief existence from 1853–56, reopened in 1869 as part of the Wedgwood Memorial Institute, the result of energetic promotion by William Woodall, secretary of the organising Committee. The Institute housed Schools of Art and Science, a public library, lecture venue, and exhibition space. It was a cultural centre created for the people of Burslem, and its intention was to educate and inspire manufacturers, designers and the general public alike. It benefited from generous public subscription, not least from Woodall himself, and from Thomas Hulme, a member of the Institute’s Technical Instruction Committee. Such support was crucial at a time when government funding was minimal, and the success of regional initiatives depended almost entirely on local patronage.

In Moorcroft’s day, the Burslem School of Art was one of the most forward-looking Schools in the country. This was in part due to its Principal, George Theaker, formerly a teacher at the Lambeth School of Art, whose collaboration with Henry Doulton in the 1870s was one of the earliest and most successful examples of an art school training designers for industry. Theaker was an innovative teacher, taking students beyond the rigid study of historical ornament which characterised the government’s design syllabus, and encouraging life and landscape drawing. His impact was strengthened by the support of Woodall, Chairman of the Technical Instruction Committee and, throughout the 1880s and 1890s, M.P. first for Stoke-upon-Trent, and then for Burslem and Hanley. Woodall used his contacts and influence to bring London speakers to the Institute (including William Morris in 1881), helping to create a vibrant cultural centre that was outward-looking in its activities. Of particular significance was Woodall’s membership of the Royal Commission on Technical Instruction, whose report of 1884 concluded that Schools of Art were failing in their responsibility to train industrial designers by placing too much emphasis on the academic study of ornament. Woodall shared the views of Morris and his followers that designers should understand the properties of the material for which they were designing, and he was committed to the establishment of practical science classes in the School. In this he reflected the progressive thinking of A.H. Church, first professor of chemistry at the Royal Academy, whose Cantor lectures, delivered at the Royal Society of Arts in 1880, were significantly entitled ‘Some points of contact between the scientific and artistic aspects of pottery’. And he attracted some of the foremost ceramic chemists as teachers: William Burton, who would soon play a defining role in the creation of art pottery at the newly established Pilkington’s Tile Factory, taught at the Institute from 1887 to 1891; and Henry Watkin, one of the first to obtain a Diploma in ceramic chemistry at the City and Guilds of London Institute, gave classes in the School of Science. These were singled out for praise in the Committee’s report of 1895:

It was a matter of congratulation that the pottery class maintained its prestige and its capable teacher […]. It was, however, a matter of regret that the facilities the classes afforded should be taken advantage of by so few students.

2

It was evidently exceptional at the time to attend this class; Moorcroft, however, was one who did. Having re-enrolled at the Institute in the autumn of 1886, he attended classes in the Schools of both Science and Art for the next nine years.

Moorcroft’s technical instruction was complemented by equally formative training at the Crown Works, where Bodley had found him work after he left school in 1886. During these apprenticeship years he acquired all the basic skills of potting, and by 1889 he was both decorating and designing. Bodley’s new Art Director was Frederick Rhead, an experienced designer who had trained in the sophisticated decorative technique of pâte-sur-pâte with Marc-Louis-Emmanuel Solon at Minton in the 1870s, before moving to Wedgwood in 1878 where he worked closely with Thomas Allen. By 1891, Moorcroft may well have expected to make his career at the Crown Works, but it was not to be, as Bodley went bankrupt in early 1892. Times were precarious for pottery designers; jobs were scarce, the work was poorly paid, and security depended entirely on the commercial fortunes of the manufacturer. Rhead joined the (short-lived) Brownfield’s Guild Pottery Society, Ltd., set up in 1892 on the lines of C.R. Ashbee’s Guild of Handicraft, and Moorcroft found work as a designer at the Flaxman Art Tile works of J & W Wade, which made majolica, transfer-printed tiles, and hand-decorated art tiles and pottery. On 13 March 1895, Edward Taylor, the forward-looking Principal of the Birmingham School of Art and (soon-to-be) co-founder of the Ruskin Pottery with his son, William Howson Taylor, was the invited speaker on Prize Day at the Burslem School; the Head of one pioneering School recognised a kindred spirit in another. Taylor paid tribute to Woodall and Hulme, whose enlightened vision and generosity provided unique facilities at the Institute, enabling the teaching of design as a practice, and encouraging a spirit of inquiry and innovation:

[…] I am glad to see from your prospectus that you have also such technical classes as will tend to link the work of the school with the industries of the town […] these special classes […] should be of the nature of art and science laboratories for students, in which research and experiment should be the main feature, and not the mere imparting of present trade tradition.

3

This was Moorcroft’s last official event as a student at the Institute, but Taylor’s emphasis on the value of experiment was one which he would take with him throughout his career.

Fig. 1 Moorcroft in the mid-1890s. Photograph. Family papers. CC BY-NC

In 1895, Moorcroft was enrolled at the National Art Training School in South Kensington. He followed classes on ornament by Lewis Day, one of the leading designers of the time, and studied ancient and modern pottery at the South Kensington Museum. The course qualified graduates of the School to teach in the provincial schools of art, but it provided little practical training in industrial design, unlike the more progressive Central School, founded in 1896 to ‘encourage the industrial application of decorative art’. Looking back on his very brief spell as Director of the Royal College of Art (as the School would be re-named from 1896), Walter Crane described the institution he found, just two years after Moorcroft’s departure, as a ‘sort of mill in which to prepare art teachers’, and its curriculum as ‘terribly mechanical and lifeless’.4 In an article published in the Pottery Gazette little more than three years after Moorcroft’s graduation,5 Louis Bilton (a ceramic artist at Doulton, Burslem), expressed regret that few of its graduates were either equipped or inclined to practise their art in industry. Most would either ‘drift away into the crowd of struggling picture painters’, or produce designs neither ‘suitable for reproduction commercially, or even practical working patterns’. But Moorcroft was not such a one. He may have obtained his Art Teaching Certificate, but within a few months of his return to Burslem he began the work of a ceramic designer for which he had long been preparing. The poor relationship of manufacturers and designers would be a recurrent topic of discussion throughout Moorcroft’s career, but in his own case he could not have found a firm more sympathetic to the progressive and enlightened design education from which he had benefited, a firm which numbered among its Directors or former Directors, William Woodall, Thomas Hulme and Henry Watkin. The firm was James Macintyre & Co., Ltd.

2. James Macintyre and Co., Ltd.

First established by W.S. Kennedy in 1838 as a manufacturer of artists’ palettes, door furniture, and letters for signs, the company moved to the Washington Works in 1847. Macintyre, Kennedy’s brother-in-law, joined in 1852, and in 1854 became its sole proprietor, employing Thomas Hulme as his manager; in 1863, he took William Woodall (his son-in-law) and Hulme into partnership. After Macintyre’s death in 1868, Woodall and Hulme expanded its production of largely functional items to include tableware, advertising ashtrays, commemoratives, household fittings, tiles, chemical and sanitary wares.

Woodall was one of the most progressive manufacturers in the Potteries. Trained as a gas engineer, and formerly Chairman of the Burslem and Tunstall Gas Company, he brought business acumen, rather than experience as a potter, to the industry. He understood the need for a skilled and educated workforce, hence his commitment to art education; but he was a pioneer, too, in the reform of working conditions, being the first to introduce an eight-hour working day in the Potteries. It was entirely consistent with his exemplary relationship with his workforce, that they should present him in 1899 with an album of staff photographs, ‘a small token of gratitude for the many benefits received at your hands’.6Hulme retired as Managing Director when Woodall entered parliament in 1880, but he kept a financial interest in the firm. A new partnership was formed, first with Thomas Wiltshaw and then, in 1887, with Henry Watkin, who had worked at Pinder Bourne in Nile Street. Other Directors were Gilbert Redgrave, who, like his father Richard Redgrave, worked in the Department of Education, and had served as Secretary to the Royal Commission; and three other members of the Woodall family, all with professional backgrounds in the gas industry: William’s two brothers, Henry and Corbet Woodall, and Corbet’s son, Corbett W. Woodall.

Shortly after the arrival of Watkin, the firm began production of porcelain insulators and switchgear for the new electricity industry. In 1893, a Limited Company was formed, and it embarked on a programme of expansion, with significant personal investment from the Directors. In addition to its development of electrical porcelain, it established an art pottery studio to complement its production of tableware and door furniture. Its beginnings were troubled. Minutes of Directors’ meetings in 1893 and 1894 record the short-lived careers of two designers, Mr Rowley and Mr Scaife, and the slightly longer appointment of Mr Wildig, whose contract was renewed for twelve months on 20 January 1894 ‘for the sum of £3 per week’. His ware, marketed as Washington Faience and decorated with coloured slip, gilding and applied relief ornament, attracted the attention of the Pottery Gazette in June 1894 which praised its ‘pure’ tones and ‘delicate’ tints. But it was not commercially successful, and in 1895 the Directors resolved to appoint a much more experienced designer, Harry Barnard, Under-Manager of the decorating studios at Doulton Lambeth. After its triumphant display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, Doulton’s art pottery enjoyed international renown; to look to this firm for their Art Director was a clear declaration of intent. A Minute of 18 January 1895 recorded Barnard’s appointment ‘at a salary of £220 for the first year, to be increased to £250 should he remain a second year’. This initial salary represented an increase of over 40% on Wildig’s salary of £156 per annum (£3 a week); Macintyre’s were evidently prepared to invest money in art pottery, although they were still uncertain of its success. Barnard had trained as a modeller, and was experienced in forms of low-relief decoration. In his unpublished memoir, ‘Personal Record’, written around 1931, he described the technique he developed. Patterns, applied with stencils, were created in coloured slip (liquid clay), further ornament being applied freehand in white slip, as had been the practice on some Doulton Lambeth stoneware:7

[…] I called it ‘Gesso’, as it was a

pâte-sur-pâte

modelling, and the tool to produce it was one that I had made. This proved to be quite a surprise, nothing like it had been seen before. To make it a commercial line, I introduced also an appliqué of ‘slip’ in a form of stencil pattern, and the slip modelling was a free-hand treatment and covered up the spaces necessary in the stencil pattern and so hid to a great extent the fact that it was applied in that way.

8

Gesso Faience was given its own elaborate backstamp, and by the end of 1895, hopes were clearly high, a Minute of 1 November 1895 recording that ‘the plastic decoration introduced by Mr Barnard promised to be commercially successful’.

But all this was to change. The firm was under increasingly acute financial pressure: an overdraft with the Bank which stood at just under £2,000 at the start of 1894, had increased to £6,000 by the summer of 1896, and on 18 January 1897 debentures were issued totalling £10,000 and funded by the Directors. In these circumstances, it is particularly surprising that a Minute of 25 January 1897 should record a decision ‘unanimously agreed’ that ‘immediate attempts be made to discover a new designer’. Just six weeks later, on 8 March 1897, Moorcroft’s appointment was announced: ‘It was reported that Mr Wm Moorcroft had been engaged, and would that day enter upon his duty as designer at a remuneration of 50/- [fifty shillings] per week’. Moorcroft’s salary (£130 p.a.) was considerably lower than Barnard’s, but at (just short of) twenty-five years of age he was much less experienced, and Barnard was still working there. But not for long. A Minute of 22 April 1897 recorded a provisional extension of Barnard’s contract, ‘at a reduced salary of £200 per annum’, and six weeks later, on 4 June 1897, the post was reduced to half-time, his salary to be paid jointly with Wedgwood. On 14 September 1897, an uncompromising Minute reported the end of his appointment: ‘Mr Harry Barnard was reported a complete failure, and it was decided to relinquish all claims on his services in favour of Messrs Wedgwood & Sons’.

Financial pressures and/or the commercial failure of Barnard’s designs doubtless motivated this dismissal; nevertheless, the firm’s growing deficit had clearly not deterred the Directors from making another appointment. Why the post was offered to Moorcroft, though, is a different matter. It is certainly the case that he was known to some of the firm’s Directors from his days at the Burslem School of Art, not least to Watkin whose classes Moorcroft had attended. He would also have been known to Watkin and Hulme from the Hill Top Chapel, where Moorcroft served as a Sunday School teacher, Watkin was a lay preacher, and Hulme was both Organist and Choirmaster. But it is true, too, that Moorcroft, newly returned from the National Art Training School, was not the standard product of state art education; his training had been a mixture of theoretical study and practical experience, learning ceramic design both through paper and clay, art and science, history and nature. He had taken full advantage of the progressive environment into which he had been born, and it was quite characteristic of Macintyre’s Directors, several of whom served on the School’s Technical Education Committee, that they recognised in him a designer with the potential to bring originality to their art pottery production.

Early in 1898, shortly after the departure of Barnard, Moorcroft was appointed Manager of Ornamental Ware, and given his own workrooms, a staff of decorators, and the exclusive services of a thrower and turner; he had sole responsibility for the training and supervision of his staff. It was the start of a period of creative collaboration, not just between Moorcroft and Macintyre’s, but also (and just as importantly) between Moorcroft and his decorators. Such was his appreciation of, and concern for, his staff that on 8 May 1899 a Directors’ Minute recorded a decision ‘at the request of Mr Moorcroft’, to give them more security. Some of these decorators may be seen in photographs surviving from the album presented to Woodall in 1899, just one week before Moorcroft’s request; two (Fanny Morrey and Jenny Leadbeater) would still be working with him more than thirty years later.

(L) Fig. 2 Decorators in Department of Ornamental Ware, J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd, 1899. Left to Right: Emily Jones, Mary (‘Polly’) Baskeyfield, Fanny Morrey, Jenny Leadbeater, Nellie Wood. Photograph. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 3 Decorators in Department of Ornamental Ware, J. Macintyre & Co. Ltd, 1899. Left to Right: Lillian Leighton, (?) Toft, Nellie Wood, Sally Cartledge, (unidentified), Annie Causley. Photograph. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

3. A New Slipware

When Moorcroft first joined Macintyre’s, he was employed to create designs for the functional wares produced in a department run by Mr Cresswell; responsibility for art wares remained with Barnard. Moorcroft designed a completely new range of decorations, with stylised floral motifs combined with abstract ornament in the form of frets and diapers. The patterns were applied by transfer printing, and finished off with gilding and enamel colours; the range would be called Aurelian. His first designs, featuring poppy, cornflower and briar rose, were registered in February 1898; these, and others, proved very popular and were produced for at least ten years. This collaboration with Cresswell’s department continued even after Moorcroft assumed responsibility for art wares. One early range was decorated with a repeating butterfly motif and other ornaments, applied in slip over a dark blue ground and finished with gilding and touches of white enamel. His most sophisticated range, however, was produced entirely in his own workshops; it was a completely original form of decorative slipware, and was named Florian ware.

For many contemporary critics, the quality of English pottery was declining, as much on account of its means of production as of its poor design. The widespread use of printed transfers, for instance, implied decoration which was merely applied, being neither literally nor metaphorically of a piece with the object. Ornament created in clay, however, had an integrity and permanence which was seen to characterise the highest form of ceramic art. The most esteemed example of this was pâte-sur-pâte, created by applying layers of slip to an unfired ceramic body, and then sculpted into low-relief decoration of great delicacy and sophistication; it was a method perfected in Solon’s studio at Minton, and subsequently adopted by Wedgwood and Doulton. In an article on the technique published in The Art Journal [AJ], Solon presented it as the model of authentic ceramic art:

[…] as a single operation is required to fire the piece and the relief decoration, which becomes, in that way, incorporated with the body, it may be regarded as essentially ceramic in character, a fundamental quality of truly good pottery […].

9

Macintyre’s had long been looking to develop a less labour-intensive, but equally authentic form of slip decoration alongside their printed, enamelled and gilded ware. Washington and Gesso Faience were both, in their different ways, ‘essentially ceramic’ in so far as their decoration was integral to the body of the vessel, but their artistic qualities were too limited to attract the interest of a discerning public. Moorcroft situated his work in this same tradition, using slip as the means of creating ornament; but he used it in a quite different way, and with quite different effects. Some of his earliest Florian designs required the application of slip to form elaborate, abstract embellishments of great delicacy. But he was soon using it to adapt for ceramics the ancient technique of cloisonné enamelling in the decoration of metalware, creating compartments with slip rather than wires, and using metallic oxides to stain the clay, rather than applying enamels to the surface of the vessel. To the decorative potential of slip, Moorcroft added the limitless possibilities of colour. A similar technique was used occasionally for the decoration of the finest art tiles, but it had not been developed for the more challenging three-dimensional surface of pottery.

(L) Fig. 4 William Moorcroft, Vases in Butterfly Ware (1898), 17cm and Aurelian ware, with Poppy motif (c.1898), 7.5cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 5 William Moorcroft, Early Florian designs with prominent slip decoration. Vases with Cornflower motif (1898), 27.5cm, and gilded floral motifs (1898), 25cm. CC BY-NC

(L) Fig. 6 William Moorcroft, Experimental vase in Butterfly design decorated with Watkin’s Leadless Glaze (1898), 20cm. CC BY-NC

(R) Fig. 7 William Moorcroft, Early experiments with underglaze colour. Narcissus (c.1900) in shades of blue, 18cm; sleeve vase with Peacock motifs in celadon and blue (1899), 27cm; Iris (c.1899), in blue, green and russet, 25cm; 2-handled coupe with floral motif (c.1900), in blue, light green and yellow, 8cm. CC BY-NC

The widespread use of on-glaze enamel colours was seen as another sign of the declining quality of ceramic art. In a series of Cantor Lectures entitled ‘Material and Design in Pottery’, William Burton examined pottery decoration through the ages. In one lecture, he deplored the ‘general substitution of hard, thin, scratchy overglaze painting in place of the rich, juicy colour produced when the colour is used underglaze’.10 The ready availability of mass-produced and standardised colours may have been welcomed by many manufacturers, but for Burton it led to lifeless, standardised effects. Research and experiment were no longer the basis of modern industrial practice, as he lamented in a lecture to the Society of Arts, ‘The Palette of the Potter’:

Mechanical finish, and not artistic excellence, is now the great aim of all manufacture; to get an even ground of colour without the least trace of variation, and to repeat this thousands of times in succession, is the point at which the modern potter is compelled to aim.

11

It was this desire to produce bright, uniform colours which largely accounted for the resistance to reducing the lead content of glazes, at a time when its dangers to pottery workers had become increasingly evident. Lead significantly reduced the melting point of the glaze, thus allowing both greater control of the firing, and a much wider range of colours.

A surviving trial vase in the Butterfly series carries the manuscript inscription ‘Watkin’s leadless glaze’ on its base, and is decorated with on-glaze enamels. It is clear, though, that Moorcroft did not pursue this method of decoration; his attitude to ceramic colour was very similar to Burton’s, for all the evident challenges. The firing temperature of a glost kiln was significantly higher than that of an enamel or muffle kiln, and the range of colours which could resist these higher temperatures without degrading was more limited. But whereas most underglaze colour was applied to the once-fired biscuit body, Moorcroft decorated the unfired clay, thereby limiting the range even further. The unusualness of this method was implied by Burton in ‘The Palette of the Potter’:

[…] the method of colouring the pottery after it has been once fired, saves the colours from being exposed to a fire angrier than need be, and the palette is extended by several colours that will endure the glazing heat, while they would be decomposed by exposure to the higher temperature of first firing.

12

The difficulty was exacerbated, too, by the temperature of Macintyre’s kilns, firing industrial ceramics at temperatures around 1300 degrees Celsius, exceptionally high for earthenware. For all these limits, though, the potential for creating particularly rich colours was all the greater. Unfired clay was more porous than a biscuit body; this allowed the oxides to penetrate more deeply, a more intense colour ensuing as a result.

Moorcroft’s technique was not only without modern parallel, it required the experimental skills of the chemist to produce viable results. Commercially available colours were of little use, even if he had wished to use them; he had to produce his own. To create colours of the rich luminous quality only achieved by chemical reactions, he needed to experiment with different combinations of oxides, glaze recipes and kiln conditions. Nor did he rely on lead-based glazes to intensify his colours or to extend the range, adapting instead to the use of fritted lead, a method which reduced both the concentration and the toxicity of the lead oxide in the glaze. Moorcroft’s diaries and notebooks from this period testify to his irrepressible spirit of enquiry. One notebook entry recorded a path yet to explore: ‘Experiment: the effect of green body and cobalt glaze’, and in his diary for 1900, he made notes on different ways of producing yellow, one of the most unstable of colours, particularly at high temperatures. Research of this kind was acknowledged as rare, but for a critic writing in the Pottery Gazette, it represented the future of ceramic art:

[…] where in the history of English ceramics can a statement be found that this chemist or that has succeeded in compounding a new body or in developing a colour hitherto unknown. […] And why not? […] The reason is that as yet, in this country, scarcely any man of high scientific attainment has been encouraged to devote himself to ceramics.

13

But Moorcroft’s interest in colour was not just scientific, it was undertaken in the service of ‘artistic excellence’. Contrasts and harmonies of colour were as essential to his conception of good design as form or ornament. In a notebook from 1900, he reflected on new experiments:

Ground to be washed all over in broken green; no ground to be prominent.

Green to be more conspicuous in design, blue forming borders.

And in another jotting from this same period, he wrote quite simply: ‘Form and colour unite to raise the highest sentiment’. The more restricted palette of underglaze colours at this early stage of Moorcroft’s work contrasted markedly with the more vibrant colours achievable with other methods of decoration. But what he produced were more subtle effects achieved by the interaction of different tones of blue or green, or the application of a light wash of secondary colour on a stained body. It was a mark of his originality that he should explore these possibilities, and of Macintyre’s faith in him that he was encouraged to do so.

4. Design and Realisation

Moorcroft’s conception of art pottery overlapped with modern thinking about ceramic decoration, drawing inspiration from the application of science to art. But it was modern, too, both in its aesthetic principles and its means of production. Pâte-sur-pâte focussed attention on the applied decoration; the vessel itself was, inevitably, secondary in its significance. Moorcroft’s ware, conversely, integrated ornament and body not just at the level of material, but also at the level of design.

It is characteristic of Moorcroft’s approach that his starting point was the introduction of new shapes, many inspired by Middle and Far Eastern, classical and early English traditions. The advantages of working with a thrower are evident. Not constrained by the use of moulds which limited the scope for variety and experiment, Moorcroft could trial a wide range of different forms. It was an invaluable asset for exploring new design possibilities, but it was also a luxury. At the end of the nineteenth century, the skilled thrower was already fast disappearing from the industrial workplace, as moulded ware became increasingly common. The economic advantages of a mould were clear, but no less clear, for some, was the resultant loss of quality; an article published in the Pottery Gazette was categorical:

There are so-called artistic potters who haven’t a throwing wheel on their premises […]. There is something about a piece of well-thrown ware, giving it a distinguished air, which the best moulded ware can never possess.

14

Woodall and his directors clearly shared that view; theirs was an ambition to provide the best facilities for the best art ware, and they were prepared to invest in it.

Moorcroft was often inspired by classical shapes, but he decorated them in his own style. To do so was in itself a gamble, both for him and for Macintyre’s. The taste for conspicuous decoration still prevailed, and contemporary design seemed to be driven by commercial opportunism not artistic sensitivity; an article in the Pottery Gazette lamented the absence of ‘any simplicity or severity of style’ in a design world dominated by ‘ornament piled on ornament’.15Moorcroft, though, was different. Notebooks and diaries of this period record constant reflection on design, form, colour and decoration, inspired by his reading or his observations in museums. A notebook from 1900 contains thoughts about the structure of ornament: ‘Where growth is suggested, give the pattern proper room to grow’, and another series of notes, on a sheet of paper dated 4 May 1900, refer to ornament in relation to the object it adorns. A recurrent theme is its integration with form, without which it can have neither purpose nor justification:

When ornament was applied to anything, it should support the construction.

The mere application of ornament is not decoration.

No ornamentation can be tolerated that is merely used for ornament.

No piece of pottery can be called good, unless it have a perfect balance of parts.

Moorcroft saw the purpose of ornament to accentuate form, not to draw attention to itself. Just as he favoured decoration which was of a piece with the body rather than applied to its surface, so too he conceived form and ornament as inseparable elements of design.

This principle was embodied in the way he worked. Design jottings from this period include many sketches of decorated shapes, the relationship of form and ornament clearly more important at this stage than the detail of the ornament itself which is often indicated in its simplest outlines. The same is true of many surviving sketches in watercolour.

Fig. 8 William Moorcroft, Experiments in the harmony of form and ornament. Vase with Violets and Butterflies (c.1900), 22cm; Urn with Narcissus (c.1900), 21cm; Knopped vase with Daisy and Cornflower (c.1898), 16cm. CC BY-NC

Fig. 9 William Moorcroft, Early design sketches, including versions of the Narcissus urn and Peacock sleeve vase illustrated in Figs 8 and 7 above. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Indeed, the numbers written on the base of his pots in the early years, all prefixed by the letter M (for Moorcroft), often indicated the unity of a given pattern on a given shape, inseparable from each other in the one defining, individual reference.

Fig. 10 William Moorcroft, Base of vase with gilded floral motifs (Fig. 5 above), showing incised initials, M number, and the Florian Ware stamp. CC BY-NC

This integrated conception of design was clearly reflected in his work. Formal academic training as practised in South Kensington consisted largely in learning the principles of ornament, tried and tested in the past; design was seen as a skill to be mastered, not to be re-invented, and certainly not as a vehicle for individuality. Ralph Wornum’s Analysis of Ornament, a central part of the official syllabus, was categorical: ‘We have not now to create Ornamental Art, but to learn it; it was established in all essentials long ago’.16 Moorcroft, however, took inspiration as much from nature as from museums, adapting the organic growth of plants to the curves and contours of a thrown pot. The first Florian designs were registered in September and October 1898, the registration number referring to particular flowers or combinations: violets, dianthus, cornflower and butterflies, poppy, iris, forget-me-nots and butterflies. What these numbers did not indicate, however, was the extensive variety in Moorcroft’s adaptations of each motif. Just as he was free to modify his shapes at will, so too, without the constraint of transfers, he could vary the decorations he created. Retail orders specified ‘Florian’, but never a particular flower or pattern; the selection was very often left, and explicitly so, to Moorcroft himself. This was a living range, rarely repetitive, always fresh; to order ‘Florian’ was to order the product of a particular moment’s inspiration, and this is what was despatched.

This individuality of design was both preserved and accentuated by his method of transferring the pattern to each pot. Pottery decoration was traditionally applied either with prints, by moulding, or by freehand drawing; Gesso Faience had used the technique of stencilling, the surround of the stencilled pattern acting as a resist to the applied layer of coloured slip. Moorcroft’s method, though, was quite different. He personally drew the decoration directly on each different shape, after which a tracing was made of it, divided into sections, which was used to apply the outline of the pattern onto each pot; decorators (known as tube-liners) then followed this outline with a thin line of slip. The creation of a tracing meant that each individual decoration could be reproduced more faithfully than freehand copying would do. And yet this process was not mechanical; each act of tracing and tube-lining was inevitably unique, each piece was re-created afresh.

Fig. 11 Variations on the Poppy motif, dated (in Moorcroft’s hand) between August and November 1899. ‘Personal and Commercial Papers of William Moorcroft’, Stoke-on-Trent City Archives, SD 1837. CC BY-NC

Fig. 12 William Moorcroft, Vase with Poppy design (c.1900), 14cm. CC BY-NC

There was scope, too, for the paintresses to display their skills. The different areas or compartments were not simply filled with flat colour, but were treated in lighter or darker washes, or with dabs of different colours, added at the decorator’s discretion. This was no automatic exercise, but required the sensitivity and technique of a watercolourist, who could make her own individual contribution to the pot. It was all the more skilful, given that the paintress was working with oxides, not with enamels; the final colours would only emerge after firing, both in the biscuit oven and in the glost kiln. This method of production preserved the integrity of the designer’s vision, but it enabled the creative contribution of thrower and turner, tube liner and paintress to the realisation of each piece. Each pot was the collaborative rendition of a design, but it was also, always, individual, the exact replica of none other.

What is striking, though, is that Moorcroft signed or initialled the ware produced in his new department, in some cases discreetly incised, but most often written plainly on the base, W. Moorcroft (or W.M.) des.

Fig. 13 Early examples of Moorcroft’s signature or Initials. CC BY-NC

He was identifying himself as the designer, but he was identifying himself, too, with each particular article. For Moorcroft, design was not about the creation of a template, but about the realisation of an object, each one unique. In his own department, he oversaw production of each piece from clay to kiln, and it was to each one that he put his name, literally, affirming his presence at the end of the process as at the beginning. It is doubtless for this reason that