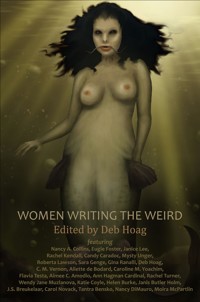

Women Writing the Weird E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dog Horn Publishing

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

"Stories that delight, surprise, that hang about the dusky edges of 'mainstream' fiction with characters, settings, plots that abandon the normal and mundane and explore new ideas, themes and ways of being." -Deb Hoag. Featuring: Nancy A. Collins, Eugie Foster, Janice Lee, Rachel Kendall, Candy Caradoc, Mysty Unger, Roberta Lawson, Sara Genge, Gina Ranalli, Deb Hoag, C. M. Vernon, Aliette de Bodard, Caroline M. Yoachim, Flavia Testa, Aimee C. Amodio, Ann Hagman Cardinal, Rachel Turner, Wendy Jane Muzlanova, Katie Coyle, Helen Burke, Janis Butler Holm, J.S. Breukelaar, Carol Novack, Tantra Bensko, Nancy DiMauro, Moira McPartlin.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 329

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WOMEN WRITING THE WEIRD

Edited by Deb Hoag

Women Writing the Weird

Published by Dog Horn Publishing at Smashwords

Copyright 2011 Deb Hoag

WEIRD

• Eldritch: suggesting the operation of supernatural influences; “an eldritch screech”; “the three weird sisters”; “stumps . . . had uncanny shapes as of monstrous creatures” —John Galsworthy; “an unearthly light”; “he could hear the unearthly scream of some curlew piercing the din” —Henry Kingsley

• Wyrd: fate personified; any one of the three Weird Sisters

• Strikingly odd or unusual; “some trick of the moonlight; some weird effect of shadow” —Bram Stoker

wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn

WEIRD FICTION

• Stories that delight, surprise, that hang about the dusky edges of “mainstream” fiction with characters, settings, plots that abandon the normal and mundane and explore new ideas, themes and ways of being. —Deb Hoag

doghornpublishing.com/women_writing_the_weird.html

The Wild Women are Loose!

Women are usually considered the more gifted with the word, written and spoken; the more cunning and craft-wise subtle of our species. When you look for the best of women’s fiction, and qualify that with fiction that breaks boundaries and takes risks, what you get is the tasty array of fiction that we present you with here: stories that will thrill, delight and shock you; stories with heart and mind and heat and depth.

When I put out a call for weird fiction, I deliberately left the definition of “weird” wide open. More than one person tagged me. “What do you mean by ‘weird’, exactly? How do you define it? What is it?”

The reply was simple. “I’ll know it when I see it. Something odd. Something unusual. What have you got that no one else would take, because it wouldn’t fit into a neat little package? That’s what I’m looking for. Think you have something that qualifies? Send me what you’ve got.”

The responses took my breath away, rich and varied and puzzling and maddening.

Come with us as we pull back the curtain and show you our wares. Step into the mind-blowing box with no doors, but with windows into the multiverse. And look for us out there, in magazines and books, online anthologies and lethal collections of wit and wisdom. We’re everywhere; you’ve just never realized how weird we can be.

Deb Hoag

September, 2011

Story List

Section One

Ys by Aliette de Bodard

Blood Willows by Caroline M. Yoachim

Six Reasons Why My Sister Hates Me by Aimee C. Amodio

Catfish Gal Blues by Nancy A. Collins

Bird in the Hand by Flavia Testa

Beneath the Skin by C.M. Vernon

Guadalupe of the Bowery by Ann Hagman Cardinal

A Stray Child by Rachel Turner

Hate Therapy by Wendy Jane Muzlanova

Section Two

In the Meantime by Janice Lee

The Scene Changes by Mysty Unger

The Difference Between My Girlfriend and a Sea Captain by Katie Coyle

Safe as Houses by Helen Burke

In Any Mistake by Janis Butler Holm

Lion Man by J.S Breukelaar

Phat is a Four-Letter Word by Deb Hoag

Minnows by Carol Novack

Section Three

Capps and Cavities by Moira McPartlin

Fall Any Way You Can by Tantra Bensko

The Gorilla in the Phone Booth by Nancy DiMauro

Gretel by Firelight by Roberta Lawson

The Strawman by Candy Caradoc

The Seasonal Witch by Rachel Kendall

Prayers for an Egg by Sara Genge

Brain Box by Gina Ranalli

The Bunny of Vengeance and the Bear of Death by Eugie Foster

Section 1

Eldritch: suggesting the operation of supernatural influences

Ys

by Aliette de Bodard

Aliette de Bodard lives and works in Paris, where she has a day job as a Computer Engineer. In her spare time, she writes speculative fiction informed by her love of history and mythology: her Aztec noir fantasies Servant of the Underworld and Harbinger of the Storm have been published by Angry Robot, while her short fiction has appeared in venues such as Asimov’s, Interzone and the Year’s Best Science Fiction. She has been a finalist for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. Visit her website at aliettedebodard.com.

“I wrote ‘Ys’ in homage to the seacoast of Brittany in France—where my father’s side of the family hails from, and where I spent years as a child,” said Aliette. “It is part of a series of fantasy stories set in France (the other being ‘Mélanie’, set in a Paris university, and which is available online at the World SF blog). The original legend of Ys has the sunken city vanish forever after Ahez betrays her father’s trust, but I thought it was appropriate to have it resurface in more ways than one. Françoise is a composite of several people I knew who had to abandon art for practical purposes (whether it be science or other dayjobs); and I packed a lot of familiar locations into the short story.”

September, and the wind blows Françoise back to Quimper, to roam the cramped streets of the Old City amidst squalls of rain.

She shops for clothes, planning the colours of the baby’s room; ambles along the deserted bridges over the canals, breathing in the smell of brine and wet ivy. But all the while she’s aware that she’s only playing a game with herself—she knows she’s only pretending that she hasn’t seen the goddess.

It’s hard to forget the goddess—that cold radiance that blew salt into Françoise’s hair, the dress that shimmered with all the colours of sunlight on water—the sharp glimmer of steel in her hand.

You carry my child, the goddess had said, and it was so. It had always been so.

Except, of course, that Stéphane hadn’t understood. He’d seen it as a betrayal—blaming her for not taking the pill as she should have—oh, not overtly, he was too stiff-necked and too well-educated for that, but all the same, she’d heard the words he wasn’t saying, in every gesture, in every pained smile.

So she left. She came back here, hoping to see Gaëtan—if there’s anyone who knows about goddesses and myths, it’s Gaëtan, who used to go from house to house writing down legends from Brittany. But Gaëtan isn’t here, isn’t answering her calls. Maybe he’s off on another humanitarian mission—incommunicado again, as he’s so often been.

Françoise’s cell phone rings—but it’s only the alarm clock, reminding her that she has to work out at the gym before her appointment with the gynaecologist.

With a sigh, she turns towards the nearest bus stop, fighting a rising wave of nausea.

“It’s a boy,” the gynaecologist says, staring at the sonographs laid on his desk.

Françoise, who has been readjusting the straps of her bra, hears the reserve in his voice. “There’s something else I should know.”

He doesn’t answer for a while. At last he looks up, his grey eyes carefully devoid of all feelings. His bad-news face, she guesses. “Have you—held back on something, Ms. Martin? In your family’s medical history?”

A hollow forms in her stomach, draining the warmth from her limbs. “What do you mean?”

“Nothing to worry about,” he says, slowly, and she can hear the “not yet” he’s not telling her. “You’ll have to take an appointment with a cardiologist. For a fetal echocardiograph.”

She’s not stupid. She’s read books about pregnancies, when it became obvious that she couldn’t bring herself to abort—to kill an innocent child. She knows about echocardiographs, and that the prognosis is not good. “Birth defect?” she asks, from some remote place in her mind.

He sits, all prim and stiff—what she wouldn’t give to shake him out of his complacency. “Congenital heart defect. Most probably a difformed organ—it won’t pump enough blood into the veins.”

“But you’re not sure.” He’s sending her for further tests. It means there’s a way out, doesn’t it? It means . . .

He doesn’t answer, but she reads his reply in his gaze all the same. He’s ninety-percent sure, but he still will do the tests—to confirm.

She leaves the surgery, feeling—cold. Empty. In her hands is a thick cream envelope: her sonographs, and the radiologist’s diagnosis neatly typed and folded alongside.

Possibility of heart deformation, the paper notes, dry, uncaring.

Back in her apartment, she takes the sonographs out, spreads them on the bed. They look . . . well, it’s hard to tell. There’s the trapeze shape of the womb, and the white outline of the baby—the huge head, the body curled up. Everything looks normal.

If only she could fool herself. If only she was dumb enough to believe her own stories.

Evening falls over Quimper—she hears the bells of the nearby church tolling for Vespers. She settles at her working table, and starts working on her sketches again.

It started as something to occupy her, and now it’s turned into an obsession. With pencil and charcoal she rubs in new details, with the precision she used to apply to her blueprints—and then withdraws, to stare at the paper.

The goddess stares back at her, white and terrible and smelling of things below the waves. The goddess as she appeared, hovering over the sand of Douarmenez Bay, limned by the morning sun: great and terrible and alien.

Françoise’s hands are shaking. She clenches her fingers, unclenches them, and waits until the tremors have passed.

This is real. This is now, and the baby is a boy, and it’s not normal. It’s never been normal.

That night, as on every night, Francoise dreams that she walks once more on the beach at Douarnenez—hearing the drowned bells tolling the midnight hour. The sand is cold, crunching under her bare feet.

She stands before the sea, and the waves part, revealing stone buildings eaten by kelp and algae, breached seawalls where lobsters and crabs scuttle. Everything is still dripping with brine, and the wind in her ears is the voice of the storm.

The goddess is waiting for her, within the largest building—in a place that must once have been a throne room. She sits in a chair of rotten wood, lounging on it like a sated cat. Beside her is a greater chair, made of stone, but it’s empty.

“You have been chosen,” she says, her words the roar of the waves. “Few mortals can claim such a distinction.”

I don’t want to be chosen, Francoise thinks, as she thinks on every night. But it’s useless. She can’t speak—she hasn’t been brought here for that. Just so that the goddess can look at her, trace the minute evolutions in her body, the progress of the pregnancy.

In the silence, she hears the baby’s heartbeat—a pulse that’s so quick it’s bound to falter. She hears the gynaecologist’s voice: the heart is deformed.

“My child,” the goddess says, and she’s smiling. “The city of Ys will have its heir at last.”

An heir to nothing. An heir to rotten wood, to algae-encrusted panels, to a city of fish and octopi and bleached skeletons. An heir with no heart.

He won’t be born, Francoise thinks. He won’t live. She tries to scream at the goddess, but it’s not working. She can’t open her mouth; her lips are stuck—frozen.

“Your reward will be great, never fear,” the goddess says. Her face is as pale as those of drowned sailors, and her lips purple, as if she were perpetually cold.

I fear. But the words still won’t come.

The goddess waves a hand, dismissive. She’s seen all that she needs to see; and Françoise can go back, back into the waking world.

She wakes up to a bleary light filtering through the slits of her shutters. Someone is insistently knocking on the door—and a glance at the alarm clock tells her it’s eleven a.m., and that once more she’s overslept. She ought to be too nauseous with the pregnancy to get much sleep, but the dreams with the goddess are screwing up her body’s rhythm.

She gets up—too fast, the world is spinning around her. She steadies herself on the bedside table, waiting for the feeling to subside. Her stomach aches fiercely.

“A minute!” she calls, as she puts on her dressing gown, and sheathes her feet into slippers.

Through the Judas hole of the door, she can only see a dark silhouette, but she’d know that posture anywhere—a little embarrassed, as if he were intruding in a party he’s not been invited to.

Gaëtan.

She throws the door open. “You’re back,” she says.

“I just got your message—” he stops, abruptly. His grey eyes stare at her, taking in, no doubt, the bulge of her belly and her puffy face. “I’d hoped you were joking.” His voice is bleak.

“You know me better than that, don’t you?” Françoise asks.

Gaëtan shrugs, steps inside—his beige trench coat dripping water on the floor. It looks as if it’s raining again. Not an unusual occurrence in Brittany. “Been a long time,” he says.

He sits on the sofa, twirling a glass of brandy between his fingers, while she tries to explain what has happened—when she gets to Douarnenez and the goddess walking out of the sea, her voice stumbles, trails off. Gaëtan looks at her, his face gentle: the same face he must show to the malnourished Africans who come to him as their last hope. He doesn’t judge—doesn’t scream or accuse her like Stéphane—and somewhere in her she finds the strength to go on.

After she’s done, Gaëtan slowly puts the glass on the table, and steeples his fingers together, raising them to his mouth. “Ys,” he says. “What have you got yourself into?”

“Like I had a choice.” Françoise can’t quite keep the acidity out of her voice.

“Sorry.” Gaëtan hasn’t moved—he’s still thinking, it seems. It’s never been like him to act or speak rashly. “It’s an old tale around here, you know.”

Françoise knows. That’s the reason why she came back here. “You haven’t seen this,” she says. She goes to her working desk, and picks up the sketches of the goddess—with the drowned city in the background.

Gaëtan lays them on the low table before him, carefully sliding his glass out of the way. “I see.” He runs his fingers on the goddess’s face, very carefully. “You always had a talent for drawing. You shouldn’t have chosen the machines over the landscapes and animals, you know.”

It’s an old, old tale; an old, old decision made ten years ago, and that she’s never regretted. Except—except that the mere remembrance of the goddess’s face is enough to scatter the formulas she made her living by; to render any blueprint, no matter how detailed, utterly meaningless. “Not the point,” she says, finally—knowing that whatever happens next, she cannot go back to being an engineer.

“No, I guess not. Still . . . ” He looks up at her, sharply. “You haven’t talked about Stéphane.”

“Stéphane—took it badly,” she says, finally.

Gaëtan’s face goes as still as sculptured stone. He doesn’t say anything; he doesn’t need to.

“You never liked him,” Françoise says, to fill the silence—a silence that seems to have the edge of a drawn blade.

“No,” Gaëtan says. “Let’s leave it at that, shall we?” He turns his gaze back to the sketches, with visible difficulty. “You know who your goddess is.”

Françoise shrugs. She’s looked around on the Internet, but there wasn’t much about the city of Ys. Or rather, it was always the same legend. “The Princess of Ys,” she said. “She who took a new lover every night—and who had them killed every morning. She whose arrogance drowned the city beneath the waves.”

Gaëtan nods. “Ahez,” he says.

“To me she’s the goddess.” And it’s true. Such things as her don’t seem as though they should have a name, a handle back to the familiar. She cannot be tamed; she cannot be vanquished. She will not be cheated.

Gaëtan is tapping his fingers against the sketches, repeatedly jabbing his index into the eyes of the goddess. “They say Princess Ahez became a spirit of the sea after she drowned.” He’s speaking carefully, inserting every word with the meticulous care of a builder constructing an edifice on unstable ground. “They say you can still hear her voice in the Bay of Douarnenez, singing a lament for Ys—damn it, this kind of thing just shouldn’t be happening, Françoise!”

Françoise shrugs. She rubs her hands on her belly, wondering if she’s imagining the heartbeat coursing through her extended skin—a beat that’s already slowing down, already faltering.

“Tell that to him, will you?” she says. “Tell him he shouldn’t be alive.” Not that it will ever get to be much of a problem, anyway—it’s not as if he has much chance of surviving his birth.

Gaëtan says nothing for a while. “You want my advice?” he says.

Françoise sits on a chair, facing him. “Why not?” At least it will be constructive—not like Stéphane’s anger.

“Go away,” Gaëtan says. “Get as far as you can from Quimper—as far as you can from the sea. Ahez’s power lies in the sea. You should be safe.”

Should. She stares at him, and sees what he’s not telling her. “You’re not sure.”

“No,” Gaëtan says. He shrugs, a little helplessly. “I’m not an expert in magic and ghosts, and beings risen from the sea. I’m just a doctor.”

“You’re all I have,” Francoise says, finally—the words she never told him after she started going out with Stéphane.

“Yeah,” Gaëtan says. “Some leftovers.”

Francoise rubs a hand on her belly again—feeling, distinctly, the chill that emanates from it: the coldness of beings drowned beneath the waves. “Even if it worked—I can’t run away from the sea all my life, Gaëtan.”

“You mean you don’t want to run away, full stop.”

A hard certainty rises within her—the same harshness that she felt when the gynaecologist told her about the congenital heart defect. “No,” she says. “I don’t want to run away.”

“Then what do you intend to do?” Gaëtan’s voice is brimming with anger. “She’s immortal, Françoise. She was a sorceress who could summon the devil himself in the heyday of Ys. You’re—”

She knows what she is; all of it. Or does she? Once she was a student, then an engineer and a bride. Now she’s none of this—just a woman pregnant with a baby that’s not hers. “I’m what I am,” she says, finally. “But I know one other thing she is, Gaëtan, one power she doesn’t have: she’s barren.”

Gaëtan cocks his head. “Not quite barren,” he says. “She can create life.”

“Life needs to be sustained,” Françoise says, a growing certainty within her. She remembers the rotting planks of the palace in Ys—remembers the cold, cold radiance of the goddess. “She can’t do that. She can’t nurture anything.” Hell, she cannot even create—not a proper baby with a functioning heart.

“She can still blast you out of existence if she feels like it.”

Françoise says nothing.

At length Gaëtan says, “You’re crazy, you know.” But he’s capitulated already—she hears it in his voice. He doesn’t speak for a while. “Your dreams—you can’t speak in them?”

“No. I can’t do anything.”

“She’s summoned you,” Gaëtan says. He’s not the doctor anymore, but the folklorist, the boy who’d seek out old wives and listen to their talk for hours on end. “That’s why. You come to Ys only at her bidding—you have no power of your own.”

Françoise stares at him. She says, slowly, the idea taking shape as she’s speaking, “Then I’ll come to her. I’ll summon her myself.”

His face twists. “She’ll still be—she’s power incarnate, Françoise. Maybe you’ll be able to speak, but that’s not going to change the outcome.”

Françoise thinks of the sonographs and of Stéphane’s angry words—of her blueprints folded away in her Paris flat, the meaningless remnants of her old life. “There’s no choice. I can’t go on like this, Gaëtan. I can’t—” She’s crying now—tears running down her face, leaving tingling marks on her cheeks. “I can’t—go—on.”

Gaëtan’s arms close around her; he holds her against his chest, briefly, awkwardly—a bulwark against the great sobs that shake her chest.

“I’m sorry,” she says, finally, when she’s spent all her tears. “I don’t know what came over me.”

Gaëtan pulls away from her. His gaze is fathomless. “You’ve hoarded them for too long,” he says.

“I’m sorry,” Françoise says, again. She spreads out her hands—feeling empty, drained of tears and of every other emotion. “But if there’s a way out—and that’s the only one there seems to be—I’ll take it. I have to.”

“You’re assuming I can tell you how to summon Ahez,” Gaëtan says, carefully.

She can read the signs; she knows what he’s dangling before her: a possibility that he can give her, but that he doesn’t approve of. It’s clear in the set of his jaw, in the slightly aloof way he holds himself. “But you can, can’t you?”

He won’t meet her gaze. “I can tell you what I learnt of Ys,” he says at last. “There’s a song and a pattern to be drawn in the sand, for those who would open the gates of the drowned city . . . ” He checks himself with a start. “It’s old wives’ tales, Françoise. I’ve never seen it work.”

“Ys is old wives’ tales. And so is Ahez. And I’ve seen them both. Please, Gaëtan. At worst, it won’t work and I’ll look like a fool.”

Gaëtan’s voice is sombre. “The worst is if it works. You’ll be dead.” But his gaze is still angry, and his hands clenched in his lap; and she knows she’s won, that he’ll give her what she wants.

Angry or not, Gaëtan still insists on coming with her—he drives her in his battered old Citroën on the small country roads to Douarnenez, and parks the car below a flickering lamplight.

Françoise walks down the dunes, keeping her gaze on the vast expanse of the ocean. In her hands she holds her only weapons: in her left hand, the paper with the pattern Gaëtan made her trace two hours ago; in her right hand, the sonographs the radiologist gave her this morning—the last scrap of science and reason that’s left to her, the only seawall she can build against Ys and the goddess.

It’s like being in her dream once more: the cold, white sand crunching under her sandals; the stars and the moon shining on the canvas of the sky; and the roar of the waves filling her ears to bursting. As she reaches the bottom of the beach—the strip of wet sand left by the retreating tide, where it’s easier to draw patterns—the baby moves within her, kicking against the skin of her belly.

Soon, she thinks. Soon. Either way, it will soon be over, and the knot of fear within her chest will vanish.

Gaëtan is standing by her side, one hand on her shoulder. “You know there’s still time—” he starts.

She shakes her head. “It’s too late for that. Five months ago was the last time I had a choice in the matter, Gaëtan.”

He shrugs, angrily. “Go on, then.”

Françoise kneels in the sand, carefully, oh so carefully. She lays the cream envelope with the sonographs by her side; and positions the paper with the pattern so that the moonlight falls full onto it, leaving no shadow on its lines. To draw her pattern, she’s brought a Celtic dagger with a triskell on the hilt—bought in a souvenir shop on the way to the beach.

Gaëtan is kneeling as well, staring intently at the pattern. His right hand closes over Françoise’s hand, just over the dagger’s hilt. “This is how you draw,” he says.

His fingers move, drawing Françoise’s hand with them. The dagger goes down, sinks into the sand—there’s some resistance, but it seems to melt away before Gaëtan’s controlled gestures.

He draws line upon line, the beginning of the pattern—curves that meet to form walls and streets. And as he draws, he speaks: “We come here to summon Ys out of the sea. May Saint Corentin, who saved King Gradlon from the waves, watch over us; may the church bells toll not for our deaths. We come here to summon Ys out of the sea.”

And, as he finishes his speech, he draws one last line, and completes his half of the pattern. Slowly, carefully, he opens his hand, leaving Françoise alone in holding the dagger.

Her turn.

She whispers, “We come here to summon Ys out of the sea. May Saint Corentin, who saved King Gradlon . . . ” She closes her eyes for a moment, feeling the weight of the dagger in her hand—a last chance to abandon, to leave the ritual incomplete.

But it’s too late for that.

With the same meticulousness she once applied to her blueprints—the same controlled gestures that allowed her to draw the goddess from memory—she starts drawing on the sand.

Now there’s no other noise but the breath of the sea—and, in counterpoint to it, the soft sounds she makes as she adds line upon line, curves that arc under her to form a triple spiral, curves that branch and split, the pattern blossoming like a flower under her fingers.

She remembers Gaëtan’s explanations: here are the seawalls of Ys, and the breach that the waves made when Ahez, drunk with her own power, opened the gates to the ocean’s anger; here are the twisting streets and avenues where revellers would dance until night’s end, and the palace where Ahez brought her lovers—and, at the end of the spiral, here is the ravine where her trusted servants would throw the lovers’ bodies in the morning. Here is . . .

There’s no time anymore where she is; no sense of her own body or of the baby growing within. Her world has shrunk to the pen and the darkened lines she draws, each one falling into place with the inevitability of a bell-toll.

When she starts on the last few lines, Gaëtan’s voice starts speaking the words of power: the Breton words that summon Ahez and Ys from their resting-place beneath the waves.

“Ur pales kaer tost d’ar sklujoù

Eno, en aour hag en perlez,

Evel an heol a bar Ahez.”

A beautiful palace by the seawalls

There, in gold and in pearls

Like the sun gleams Ahez

His voice echoes in the silence, as if he were speaking above a bottomless chasm. He starts speaking them again—and again and again, the Breton words echoing each other until they become a string of meaningless syllables.

Françoise has been counting carefully, as he told her to; on the ninth repetition, she joins him. Her voice rises to mingle with Gaëtan’s: thin, reedy, as fragile as a stream of smoke carried by the wind—and yet every word vibrates in the air, quivers as if drawing on some immesurable power.

“Ur pales kaer tost d’ar sklujoù

Eno, en aour hag en perlez,

Evel an heol a bar Ahez.”

Their words echo in the silence. At last, at long last, she rises, the pattern under her complete—and she’s back in her body now, the sand’s coldness seeping into her legs, her heart beating faster and faster within her chest—and there’s a second, weaker heartbeat entwined with hers.

Slowly, she rises, tucks the dagger into her trousers pocket. There’s utter silence on the beach now, but it’s the silence before a storm. Moonlight falls upon the lines she’s drawn—and remains trapped within them, until the whole pattern glows white.

“Françoise,” Gaëtan says behind her. There’s fear in his voice.

She doesn’t speak. She picks up the sonographs and goes down to the sea, until the waves lap at her feet—a deeper cold than that of the sand. She waits—knowing what is coming.

Far, far away, bells start tolling: the bells of Ys, answering her call. And in their wake the whole surface of the ocean is trembling, shaking like some great beast trying to dislodge a burden. Dark shadows coalesce under the sea, growing larger with each passing moment.

And then they’re no longer shadows, but the bulks of buildings rising above the surface: massive stone walls encrusted with kelp, surrounding broken-down and rotted gates. The faded remnants of tabards adorn both sides of the gates—the drawings so eaten away Françoise can’t make out their details.

The wind blows into her face the familiar smell of brine and decay, of algae and rotting wood: the smell of Ys.

Gaëtan, standing beside her, doesn’t speak. Shock is etched on every line of his face.

“Let’s go,” Françoise whispers—for there is something about the drowned city that commands silence, even when you are its summoner.

Gaëtan is looking at her and at the gates; at her and at the shimmering pattern drawn on the sand. “It shouldn’t have worked,” he says, but his voice is very soft, already defeated. At length he shakes his head, and walks beside her as they enter the city of Ys.

Inside, skeletons lie in the streets, their arms still extended as if they could keep the sea at bay. A few crabs and lobsters scuttle away from them, the click-click of their legs on stone the only noise that breaks the silence.

Françoise holds the sonographs under her arms—the cardboard envelope is wet and decomposing, as if the atmosphere of Ys spreads rot to everything it touches. Gaëtan walks slowly, carefully. She can imagine how he feels—he, never one to take unconsidered risks, who now finds himself thrust into the legends of his childhood.

She doesn’t think, or dwell overmuch on what could go wrong—that way lies despair, and perdition. But she can’t help hearing the baby’s faint heartbeat—and imagining his blood draining from his limbs.

There’s no one in the streets, no revellers to greet them, no merchants plying their trades on the deserted marketplace—not even ghosts to flitter between the ruined buildings. Ys is a dead city. No, worse than that: the husk of a city, since long deserted by both the dead and the living. But it hums with power: with an insistent beat that seeps through the soles of Françoise’s shoes, with a rhythm that is the roar of the waves and the voice of the storm—and also a lament for all the lives lost to the ocean. As she walks, the rhythm penetrates deeper into her body, insinuating itself into her womb until it mingles with her baby’s heartbeat.

Françoise knows where she’s going: all she has to do is retrace her steps of the dream, to follow the streets until they widen into a large plaza; to walk between the six kelp-eaten statues that guard the entrance to the palace, between the gates torn off their hinges by the onslaught of the waves.

And then she and Gaëtan are inside, walking down corridors. The smell of mould is overbearing now, and Françoise can feel the beginnings of nausea in her throat. There’s another smell, too: underlying everything, sweet and cloying, like a perfume worn too long.

She knows who it belongs to. She wonders if the goddess has seen them come—but of course she has. Nothing in Ys escapes her overbearing power. She’ll be at the centre, waiting for them—toying with their growing fear, revelling in their anguish.

No. Françoise mustn’t think about this. She’ll focus on the song in her mind and in her womb, the insidious song of Ys—and she won’t think at all. She won’t . . .

In silence they worm their way deeper into the cankered palace, stepping on moss and algae and the threadbare remnants of tapestries. Till at last they reach one last set of great gates—but those are of rusted metal, and the soldiers and sailors engraved on their panels are still visible, although badly marred by the sea.

The gates are closed—have been closed for a long time, the hinges buried under kelp and rust, the panels hanging askew. Françoise stops, the fatigue she’s been ignoring so far creeping into the marrow of her bones.

Gaëtan has stopped too; he’s running his fingers on the metal—pushing, desultorily, but the doors won’t budge.

“What now?” he mouths.

The song is stronger now, draining Françoise of all thoughts—but at the same time lifting her into a different place, the same haven outside time as when she was drawing the pattern on the beach.

There are no closed doors in that place.

Françoise tucks the envelope with the sonographs under her arm, and lays both hands on the panels and pushes. Something rumbles, deep within the belly of the city—a pain that is somehow in her own womb—and then the gates yield, and open with a loud creak.

Inside, the goddess is waiting for them.

The dream once more: the rotten chairs beside the rotten trestle tables, the warm stones under her feet. And, at the far end of the room, the goddess sitting in the chair on the dais, smiling as Françoise draws nearer.

“You are brave,” she says, and her voice is that of the sea before the storm. “And foolish. Few dare to summon Ys from beneath the waves.” She smiles again, revealing teeth the colour of nacre. “And fewer still return alive.” She moves, with fluid, inhuman speed; comes to stand by Gaëtan, who has frozen, three steps below the empty chair. “But you brought a gift, I see.”

Françoise drags her voice from an impossibly faraway place. “He’s not yours.”

“I choose as I please, and every man that comes into Ys is mine,” the goddess says. She walks around Gaëtan, tilting his head upwards, watching him as she might watch a slave on the selling-block. Abruptly there’s a mask in her hand—a mask of black silk that seems to waver between her fingers.

That legend, too, Gaëtan told her. At dawn, after the goddess has had her pleasure, the mask will tighten until the man beneath dies of suffocation—one more sacrifice to slake her unending thirst.

Françoise is moving, without conscious thought—extending a hand and catching the mask before the goddess can put it on Gaëtan’s face. The mask clings to her fingers: cold and slimy, like the scales of a fish, but writhing against her skin like a maddened snake.

She meets the goddess’s cold gaze—the same blinding radiance that silenced her within the dream. But now there’s power in Françoise—the remnants of the magic she used to summon Ys—and the light is strong, but she can still see.

“You dare,” the goddess hisses. “You whom I picked among mortals to be honoured—”

“I don’t want to be honoured,” Françoise says, slowly. The mask is crawling upwards, extending coils around the palm of her hand. She’s about to say “I don’t want your child”, but that would be a lie—she kept the baby, after all, clung to him rather than to Stéphane. “What I want you can’t give.”

The goddess smiles. She hasn’t moved—she’s still standing there, at the heart of her city, secure in her power. “Who are you to judge what I can and can’t give?”

The mask is at her wrist now—it leaves a tingling sensation where it passes, as if it had briefly cut off the flow of blood in her body. Françoise tries not to think of what will happen when it reaches her neck—tries not to fear. Instead, as calmly as she can, she extends the envelope to the goddess. When she moves, the mask doesn’t fall off, doesn’t move in the slightest—except to continue its inexorable climb upwards.

Mustn’t think about it. She knew the consequences when she drew her pattern in the sand; knew them and accepted them.

So she says to the goddess, in a voice that she keeps devoid of all emotions, “This is what you made.”

The goddess stares at the envelope as if trying to decide what kind of trap it holds. Then, apparently deciding Françoise cannot harm her, she takes the envelope from Françoise’s hands, and opens it.

Slowly, the goddess lifts the sonographs to the light, looks at them, lays them aside on the steps of the dais. From the envelope she takes the last paper—the diagnosis typed by the radiologist, and looks at it.

Silence fills the room, as if the whole city were holding its breath. Even the mask on Françoise’s arm has stopped crawling.

“This is a lie,” the goddess says, and her voice is the lash of a whip. Shadows move across her face, like storm-clouds blown by the wind.

Françoise shrugs, with a calm she doesn’t feel. “Why would I?” She reaches out with one hand towards the mask, attempts to pull it from her arm. Her fingers stick to it, but it will not budge. Not surprising.

“You would cast my child from your womb.”

Françoise shakes her head. “I could have. Much, much earlier. But I didn’t.” And the part of her that can’t choke back its anger and frustration says, “I don’t see why the child should pay for the arrogance of his creator.”

“You dare judge me?” The goddess’ radiance becomes blinding; the mask tightens around Françoise’s arm, sending a wave of pain up her arm, pain so strong that Françoise bites her lips not to cry out. She fights an overwhelming urge to crawl into the dirt—it doesn’t work, because abruptly she’s kneeling on the floor, with only shaking arms to hold up her torso. She has to abase herself before the goddess—before her glory and her magic. She, Françoise, is nothing; a failure, a flawed womb. An artist turning to science out of greed; an engineer drawing meaningless blueprints; a woman who used her friend’s feelings for her to bring him into Ys.

“If this child will not survive its birth,” the goddess is saying, “you will have another. I will not be cheated.” Not by you, she’s saying without words. Not by a mere mortal.

A wave of power buffets Françoise, bringing with it the smell of wind and brine; of wet sand and rotten wood. Within her, the power of the goddess is rising—Françoise’s belly aches as if fingers of ice were tearing it apart. Her baby is twisting and turning, kicking desperately against the confines of the womb, voicelessly screaming not to be unmade, but it’s too late.

She wants to curl up on herself and make the pain go away; she wants to lie down, even if it’s on slimy stone, and wait until the contractions of her belly have faded, and nothing remains but numbness. But she can’t move. The only way to move is towards the algae-encrusted floor, to grovel before the goddess.

Gaëtan was right. It was folly to come here; folly to hope to stand against Ahez.

Françoise’s arms hurt. She’s going to have to yield. There’s no other choice. She—

Yield.

She’s a womb, an empty place for the goddess to fill. She has been chosen, picked out from the crowd of tourists on the beach—chosen for the greatest of honours, and now chosen again, to bear a child that will be perfect. She should be glad beyond reason.

Yield.

The mask is crawling upwards again—it’s at her shoulder now, flowing towards her neck, towards her face. She knows, without being able to articulate the thought, that when it covers her face she will be lost—drowned forever under the silk.

Everything is scattering, everything is stripped away by the power of the goddess—the power of the ocean that drowns sailors, of the storm-tossed seas and their irresistible siren song. She can’t hold on to anything. She—has to—

There’s nothing left at her core now; only a hollow begging to be filled.

And yet . . . and yet in the silence, in the emptiness of her mind is the song of Ys, and the pattern she drew in the sand; in the silence of her mind, she is kneeling on the beach with the dagger still in her hand, and watching the drowned city rise from the depths to answer her call.

Slowly, she raises her head, biting her lips not to scream at the pain within her—the pain that sings yield yield yield. Blood floods her mouth with the taste of salt, but she’s staring at the face of the goddess—and the light isn’t blinding, she can see the green eyes dissecting her like an insect. She can—

She can speak.