4,79 €

Mehr erfahren.

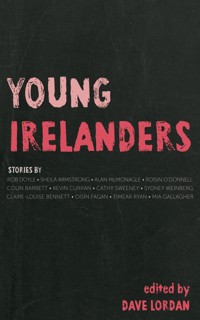

- Herausgeber: New Island

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Young Irelanders is an exciting anthology of short stories that will open your eyes and soul to a new and continually evolving Irish literary scene, featuring a selection of Ireland's most gifted and daring contemporary short-fiction writers: Sheila Armstrong, Claire-Louise Bennett, Colin Barrett, Kevin Curran, Rob Doyle, Oisín Fagan, Mia Gallagher, Alan McMonagle, Roisín O'Donnell, Cathy Sweeney, Eimear Ryan, Sydney Weinberg. Young Irelanders reinvigorates the traditional Irish short story with a palpable sense of adventure. From Kevin Curran's heart-wrenching portrayal of bullying and suicide, to Roisin O'Donnell's beautifully poignant narrative of a Brazilian girl's journey to Ireland for love, to Rob Doyle's searing tale of infidelity, the characters in these tales are searching for love, for courage, for release, and for glory. Surging with an energy and vigour synonymous with this new generation of Irish writers, the stories are in turn profound, shocking, lyrical and dark, while remaining endlessly and exuberantly inventive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

YOUNG IRELANDERS

YOUNG IRELANDERS

YOUNG IRELANDERS

First published in 2015

by New Island Books,

16 Priory Hall Office Park,

Stillorgan,

County Dublin,

Republic of Ireland.

www.newisland.ie

Introduction copyright © Dave Lordan, 2015. The stories are the copyright property of their respective authors.

Dave Lordan and the contributing authors have asserted their moral rights.

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84840-441-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84840-442-7

MOBI ISBN: 978-1-84840-443-4

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

New Island received financial assistance from The Arts Council (An Chomhairle Ealaíon), 70 Merrion Square, Dublin 2, Ireland.

Contents

Introduction Dave Lordan (ed.)

Saving Tanya Kevin Curran

How to Learn Irish in Seventeen Steps Roisín O’Donnell

Summer Rob Doyle

17:57:39–20:59:03 Mia Gallagher

Doon Colin Barrett

Three Stories on a Theme Cathy Sweeney

Retreat Eimear Ryan

Oyster Claire-Louise Bennett

The Remarks Alan McMonagle

Omen in the Bone Sydney Weinberg

The Tender Mercies of its Peoples Sheila Armstrong

Subject Oisín Fagan

Dave Lordan

Dave Lordan is a writer, editor and creative writing workshop leader based in Dublin. He is the first writer to win Ireland’s three national prizes for young poets: the Patrick Kavanagh Award in 2005, the Rupert and Eithne Strong Award in 2008, and the Ireland Chair of Poetry Bursary Award in 2011 for his collections The Boy in The Ring and Invitation to a Sacrifice, both published by Salmon Poetry. In 2010 Mary McEvoy starred in his debut play, Jo Bangles, at the Mill Theatre, directed by Caroline Fitzgerald. Wurm Press published his acclaimed alt.fiction debut, First Book of Frags, in 2013. Also in 2013, in association with RTÉ’s Arena and New Island Books, he designed and led Ireland’s first ever on-air creative writing course, New Planet Cabaret. Lost Tribe of the Wicklow Mountains, published in late 2014 by Salmon Poetry, is his newest collection of poetry. Lordan has performed his own work and led poetry and fiction workshops at numerous venues and festivals throughout Ireland, the UK, Europe and North America. He is a contributing editor and short fiction mentor for The Stinging Fly and he teaches contemporary poetry and critical theory on the MA in Poetry Studies at the Mater Dei Institute of DCU. He is the founding editor of the popular and iconoclastic website bogmanscannon.com and he tweets @BogmansCannon.

Introduction

‘Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.’

– William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, 7:2

There are, have been, and will be innumerable ‘Irelands’, far too may for one kind of vision, one kind of fiction, one anthology, no matter how wide-ranging, to encompass. What this anthology celebrates and highlights is the emergence in Ireland in recent years of a young and versatile literature open to multiple experiences and points-of-view, to techniques, experiences, and accents previously little heard of or long repressed and excluded – without claiming privileged institutional or cultural status for any.

Perhaps there are no more interesting or various ‘Irelands’ for literature to feed on today than there have been at any other time in our history. Certainly, Ireland was at least as intellectually cosmopolitan and internationalised in the 1790s, that wonderful revolutionary decade, as it is today, to mention only one example. However, I believe there are more talented writers, in short fiction especially, coming from a far wider range of places and perspectives, with more things to say and more ways of saying, than ever before.

Although there is no simple or direct relationship between the progress of a nation and the kind of fiction its writers produce, there is obviously some connection. Ireland in its twentieth- century incarnation was really a nation of a defeated and downtrodden majority, a post-colonial people whose utopian hopes had been dashed and whose pride had to be swallowed and kept down, with painful difficulty, for a very long time. It is no coincidence that we became in this period the best in the world at producing the fiction of grief and of mourning, whether it is the damnation of the dead and the undead that animates the angry, vengeance-seeking grief of Liam O’Flaherty, or the instinct to sanctify the fallen, the downtrodden and the doomed that moves us so often in the work of Des Hogan, John McGahern, Mary Costello, Claire Keegan, Edna O’Brien and William Trevor, to name but a few.

The near unanimity of this variously shaded style of melancholy naturalism, despite the vast talents of its finest exponents, also quite clearly testifies to the monoculturalism that afflicted the Republic of Ireland in the twentieth century, and tempts one to describe Irish fiction in this period as a provincial or regional literature rather than a truly national one. A national literature that we can all feel part of, like that of the French, the Mexicans, or of the Egyptians, accommodates and encourages far more styles and approaches than Irish fiction has so far been generally able to, aside from the obvious exceptions. The most influential book in Irish twentieth-century fiction, it’s ur-book and intertext-in- chief, is Joyce’s Dubliners, a melancholy, naturalist classic for all times and all places. But Joyce, and after him Flann O’Brien and Beckett, wrote several other canonical works of fiction, whose influence on Irish fiction writers, in all but the rarest of cases, has yet to come to pass.

The diversity, alongside the success, of Irish short fiction in recent years gives grounds for being optimistic about the arrival of truly pluralistic and inclusive Irish literature in the near future, one in which no particular style or method is elevated to scriptural or exclusively state-subsidized status. There is unquestionably a new wave of young fictioneers emerging from our world-class small press and journal scene who are worth reading and supporting and who, between them, are building a sustainable audience for alternatives to the melancholy naturalist mode.

Some, but my no means all, of this new wave are represented in this Young Irelanders anthology, an anthology that makes no claims to totality or grand authority whatsoever. Think of it as primer, a mix-tape that will open your eyes and your soul to a new and continually evolving scene that is out there waiting to be discovered in literary magazines, small press collections, and in off-piste literary events of all sorts. You’ll find your own favourites, I’m sure.

I am proud to present you with twelve new and diverse creations, from twelve new and diverse creators, with the Young Irelanders anthology.

My sincere thanks to all contributing writers, and also to the team at New Island Books.

– Dave Lordan

Kevin Curran

Kevin Curran’s debut novel, Beatsploitation, was published in 2013 by Liberties Press. He was a winner of the inaugural Irish Writers’ Centre Novel Fair. His work has previously appeared in The Stinging Fly. He has received an Arts Council of Ireland bursary for his second novel, Citizens, which will be published in 2016.

Saving Tanya

I only got on his Facebook once. He would always log out, but one day, yeah, he closed over the laptop when Mam came up and asked him for help with something, cos he always helped Mam with everything, and when I opened it, like, he was still logged in. I was gonna frape him, send loads of PMs to all the girls and put up a status like, I dunno, I love dick, or Wish I had a dick, or I just did a great shit, but then, like, then I saw the private messages he’d been sent, and I felt really bad for him, angry too, yeah, cos I knew some of the lads messaging him, and they always smiled at me or Mam, or patted my shoulder and said things like, ‘Sam, the main man, how’s your bro?’ And then the messages they’d sent Jordan were cat. There was loads of them: U Black Cunt and Can u hear me? Can u hear me? No. One. Likes. U.

When he’d be taking me to town or to Deli Burger or GameStop I used be all proud and happy, cos Jordan, when he walked with you, yeah, he made you feel like a boss. Him and his magic aftershave would make all the girls from school call over and say hello. Even the girls from my class who I wanted to be with who never even normally noticed me would come over. They’d, like, all smile, or wave big, stupid waves from across the street, and the bigger girls, the ones from his year, yeah, would rub my head like I was a stupid dog or something and say, ‘Oh, Jordan, he’s got your eyes. He’s gonna be a heartbreaker too,’ and they’d all giggle and bring their shoulders up to their ears or mess with their hair. Emmanuel said they just liked Jordan and me cos we’re half-caste, and that if he was half-caste they’d all come over to him too. But he was just jealous cos he was bleaching and still no girls noticed him.

But, what is it, sometimes if we were at the bus stop, or like, walking with the girls cos they wouldn’t leave us alone going to the shops, some of those lads whose faces I saw on the private messages on Facebook would walk by. Three or four of them, yeah, all bumping into each other, and they’d see us coming towards them, like, and bring their hands to their mouths like they was hiding their face, and they’d say things like, nigger, or deaf prick wanker. Cos they’d go past so quick, and their mouths would be covered, Jordan wouldn’t catch what they’d say. But I would, and the girls would too, and I’d feel let down by Jordan, yeah, like, I dunno, disappointed, cos like, he wouldn’t fight back. And the girls’ smiles would, like, turn, as if they just got a Mega-Sour or something, and things would go weird. I know he couldn’t hear them, but they still said it and got away with it. All. The. Time.

My mam went mad after he was found. He was only missing a day, cos, like, his friend Dave knew where to look. Anyways, my mam was screaming and shouting and groaning, and all the neighbours just stood around being real quiet, whispering how he looked so peaceful, like he was sleeping, but I knew, yeah, that that was bollix cos he never slept with his mouth closed cos he had problems with his nose and his breathing used always keep me awake, and I used throw things down at him or rock the bunk or just tell him to shut up.

Sometimes after, when all the neighbours were gone, she’d fall to the ground and groan like an angry dog, and me or Woody or my little sister would try and hug her or pick her up, but she’d throw her arms out and tell us to leave her be. Times like that, yeah, when she’d go into a little ball and cry and cry, I’d wish I could help her, but I’d just go upstairs and find a jumper Jordan put in the wash but Mam never washed, and I would bring it to bed with me and hide under the cover and put my face in it, yeah, like a mask, like, what is it, I knew, I knew if Jordan were still there Mam wouldn’t be so sad, and the house wouldn’t be in such a mess and my clothes wouldn’t be stinking and I wouldn’t be robbing Febreze from Spar to spray all over them, cos I knew I was starting to smell like shit.

I remember playing football with him, just the two of us, yeah. I asked and asked, and then he said, ‘Just ten minutes cos I’m busy.’ But he wasn’t, cos he was doing nothing only watching Jeremy Kyle, even though, like, I saw the lads he hung around with go past the house. So, what is it, we went onto the green and he stood around with his phone looking bored, and even though it was roasting, yeah, he had his hat on, the woolly one he always had on cos it went over his ear and hid his hearing aid. Anyway, I was running towards him and doing my stepovers and sending him the wrong way, and what is it, like, it was class cos every time, yeah, I’d nick it past him, he’d smile and say, ‘Again, again,’ and make me go back and get ready, and then, what is it, I was running, dribbling up to him, and he musta got a message cos I heard it and he looked at his phone and then, like, I was about to do my first stepover cos I was, like, real close, but still far enough away, yeah, and he just jumped at me, two-footed, man! He hacked me out of it, and I screamed out in bits on the ground, and I was like, I was crying and all. I feel bad now cos I got thick and, what is it, I was holding my shin and it was stinging and cos Jordan had tackled me he was on the ground too, and his hat had come off and his hearing aid was hanging loose and I went, ‘Hah, you deaf bastard, I’m telling Ma.’ He looked at me all sad, disappointed kind of, like he was gonna cry, and like, what is it, Jordan, yeah, he never cried, ever. And when he looked behind him those lads were walking backwards away from us into the lane to Lidl, and their phones were out and pointing at us and they were laughing. I grabbed the ball and just left Jordan there and tried to run home, but my shin and ankle was killing me, and I already felt like, ye know, I felt real tight for shouting that at Jordan, and I didn’t know if I was crying cos I was sore or cos I loved my older brother and shouldn’t have done that, like, shout at him like that, especially in front of those lads. Jordan musta come straight home after me, cos when I went up to the Xbox I heard the front door close and I knew it was him.

What is it, I played GTA all day and then went to bed and had to ask Woody to give me a hoosh onto the bunk cos my shin and ankle was still in bits. I was asleep, like, I didn’t even hear him come in, when Jordan whispered in my ear, yeah, he musta shook me or something, and he whispered, ‘Sam, Sam, you awake? I’m sorry, Sam. I shouldn’t have done that earlier. Those lads texted me and took the piss. It was bad out. I’m sorry.’ And he shook my head, and it felt great again to be his friend, but I never said okay or thanks or sorry. And that makes me feel bad now cos it might’ve helped him.

The next morning I had loads of mails, yeah, cos, like, someone had tagged me in a video, and the whole school, for real, like, the whole town had Liked it or Commented on it. Tommo had put it up the night before with the tagline, something about this deaf prick can’t even kick a ball, and it was the video of me doing the stepovers and Jordan breaking me up and me crying, and Jordan on the ground trying to put his hearing aid back and taking his hat and looking over to the camera and the lads in the lane. You could hear them saying all sorts of stuff about him and me. And, what is it, you could hear me shout, ‘You deaf bastard, I’m telling Ma,’ and I felt bad out.

It was a bit after the Facebook thing that we moved house. She never said, yeah, but I think Mam musta heard from someone about all the Facebook stuff, cos like, what is it, I wasn’t friends with Jordan so I couldn’t see his page, but like, sometimes if someone I was friends with commented on a post, like, even to tell those lads to leave it out, I’d see the stuff. Maybe I shudda told my mam earlier, but, like, what is it, I didn’t know it was such a big deal, an’ anyways, we moved town. But Facebook isn’t a house or a street you can leave behind, it’s this thing – not even a friend, cos it doesn’t ever really be nice to you – that you can never leave behind. And everyone on it, all the bad people, no matter where you go, yeah, they follow you and like, be like, always whispering, even sometimes roaring in your ear, like they did for Jordan, with everyone else hearing it too, like, about how bad you are, and like, how bad your life is. And no matter what, even your new friends in your new town would see it and wonder do you deserve it.

The inquest thing was put off by a few months after Mam asked the judge guy to look at Jordan’s phone cos the cops had restored the factory settings on it and some old messages had come up. The judge lad said, like, he was asking Facebook to look at Jordan’s account and go through his friends’ messages too, yeah, cos Mam had convinced him Facebook was to blame as well. And when they said they would look at it, that’s when Mam banned us from Facebook forever. Ye can’t, though, ban Facebook. That’s bad out, like. It’s always there, it’s everywhere, and everyone lives on it, even if Mam says ye can’t go on it. But, like, I felt bad when I did go on it. Eliza never did. And she, yeah, she always whispered, ‘I’m telling Mam,’ when she caught me on it. ‘You know what Mam said,’ Eliza would say. Yeah, Mam said it’s Facebook’s fault. But it’s not. It was the text messages, and Mam still uses her phone.

A few months later, yeah, Mam had to go see the judge again and Auntie Nelly had to come to our house, what is it, cos Mam was all upset leading up to it, like crying and stuff. All. The. Time. And Mam was staying in her bedroom and not coming out in the morning, even when we were going to school or being up when we got home, yeah. Me, like, I’m okay, yeah, like if I got upset I’d go to bed and get Jordan’s aftershave cos he had nearly a whole bottle left – my mam got it for him for his birthday – and I’d spray it, just a little, tssss, yeah, on my pillow, and then be okay again. You see, Auntie Nelly washed all his clothes and pillowcases and all that so I’d have to spray his spray. Eliza, though, what is it, she was in the box room on her own, and she was only in first year, yeah, and me and Woody were bigger and in our room, but she cried a lot and banged on Mam’s door and sobbed she wanted to come in, but all you’d hear would be, ‘Go away, Lizzie,’ as if Mam was, like, under the covers or had her head in the pillow too. Sometimes, yeah, at night I’d think of all four of us awake, but quiet and crying all alone in our pillows, wishing so hard that Jordan was here, and I’d think if only we were all together. But I never did anything to make it happen.

An’ anyways, Auntie Nelly came that week, and I heard her talking, yeah, in Mam’s room, saying, ‘You’ve got to get it together, Marie. Look at me, Marie. You’ve got to get it together. You’re gonna lose them.’ And, what is it, I wondered then had Nelly been talking to Fiona too, cos like, Fiona was a woman I’d met in school who wasn’t a teacher cos all she did was smile and whisper and look at me like I was sick, and say, ‘What did you have for breakfast, Sam?’ and ‘Did you wash your clothes yourself, Sam?’ and, what is it, I was angry with myself, cos like, I forgot to spray the Febreze on my shirt and jumper in the morning and she musta smelt the bang off me and in that room, yeah, and with just me and Fiona and another lady, it was so quiet you could hear my belly, like, going mental.