Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

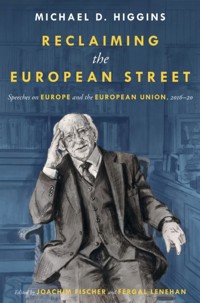

'From Covid-19 we have been reminded, through tragedy and suffering, that we have a shared, globalized vulnerability common to all humanity … The lessons of necessity and solidarity learned during the pandemic must now inform a European-led transition to a just and ecologically sustainable society in its aftermath.' President Michael D. Higgins is one of the few public intellectuals to engage regularly with the abstract idea of an alternative European space, and to consistently reimagine it. Yet public discussions regarding Ireland's closer links with the European Union often remain purely utilitarian and economic, or take place only within academia. Here, in Reclaiming the European Street, in over twenty lively discourses, President Higgins lays out his vision for Europe. This is the first gathering of all the President's Europe-themed speeches from 2016 to 2020. They deal with wide-ranging contemporary issues, from the 1916 Centenary celebrations to the Brexit decision of June 2016 and the Covid-19 pandemic: the latter, in particular, has shunted the European Union into a worldwide arena through its role in helping Member States cope with economic and human fallout. As well as translations into Irish, French and German, a comprehensive introduction by the editors gives context to the speeches within wider Irish and European intellectual history. Stamped by President Higgins' inimitable intellectual rigour and empathy, these documents also express fundamental concerns on behalf of the Irish people. His generous pluralist view of history and embracing of a liberal secular society make this volume essential reading for any citizen seeking to understand the role of Ireland within the European Union.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 550

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

the lilliput press

dublin

Preface

This collection of some of my recent speeches covers a five-year period from 2016 to 2020, a tumultuous time that commenced with the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump in the United States and concludes with the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic with all its personal, social, cultural and economic consequences.

These speeches I gave in that period were to European audiences drawn from the institutional matrix of the European Union. That matrix had, and still has, a specific form of discourse. I was conscious, however, of a more raucous, angry and, at times, disappointed discourse echoing from the European Street. It was from a public bearing not just a memory, but a retained set of experiences that were still being felt as a result of the responses made to the banking-sourced financial and economic disaster of 2008. The name given by so many in the European Street to that response was ‘austerity’.

In so many of the speeches that follow, I sought to address the assumptions of the economic model that had brought us to both the crisis of 2008 and the response that had been made to it. The reception I received was encouraging in some settings. In a few places, a particular speech might draw a bad-tempered dismissal of my opinion and the sources I quoted as the words of mavericks who did not understand economics; that their decision or mine to critique or even to speak of ‘neo-liberalism’ was to use a cliché.

I believe that a new challenge with a global response has changed all that. What was not tolerated in the discourse is now part of the necessary response to COVID-19 – a source of policy for an activist and even entrepreneurial state, social protection and collective responses that now can allow for a discussion of the ecological, social and economic intermix that is unavoidable for policy.

The global loss of life and disruption to our daily lives resulting from COVID-19 is unprecedented in living memory. Indeed, it was only in 2019 that I held a seminar at Áras an Uachtaráin to mark the centenary of the last pandemic of similar magnitude, that of the so-called and misnamed Spanish flu, the address from which is included in this book.

From COVID-19 we have been reminded through tragedy and suffering that we have a shared, globalized vulnerability that is common to all humanity, one that knows no borders. We are learning how we must make urgent changes to improve resilience in a range of essential areas, such as work, healthcare and housing. We have been forced to recognize our dependence on our public-sector frontline workers, and the state’s broader role in mitigating this crisis and saving lives.

COVID-19 has magnified the shortcomings of an insufficient, narrow, indeed failed and failing paradigm of economy with all its imbalances, inequities and injustices. Yet, responding to COVID-19 has proved, if ever proof were required, that government is needed, and can act decisively when the will is there. It has reminded us of how so many are only ever one wage payment away from hardship; how the self-employed or workers in the so-called ‘gig’ economy lack security and basic employment rights; how private tenants in under-regulated housing markets are at the mercy of their landlords; how many designated ‘key workers’, those providing essential services, are shamefully undervalued and underpaid.

How regrettable it is that it has taken a pandemic of this magnitude to demonstrate these stark facts so vividly. What a tragedy it is that it has required the pandemic’s toll, the millions of lives cut short across the world, to establish, or rekindle, widespread appreciation of work in the public sphere and the importance in the economy of the public good – and, in terms of our shared future, the state’s benign and transformative capacity. Averting our gaze from these grim truths is no longer an option.

There is now a widespread, recovered recognition across the streets of Europe, and indeed beyond, not only of the state’s positive role in managing such crises, but of how it can play a deeper, entrepreneurial, transformative role in our lives for the better. The erosion of the state’s role, the weakening of its institutions, and the undermining of its significance for over four decades has left a less just and more precarious society and economy, one ill-prepared for seismic shocks such as COVID-19.

The role of the state, thus, needs to be recovered, understood, accepted and defined anew, as well as the concept of sovereignty, in such a way that sovereignty is shared, can flow for the benefit of citizens beyond borders, can have a comparative and regional character; one that has the capacity to be exemplary for global economic systems.

Better ideas that will generate more inclusive, transformative and transparent policies are now required – ideas based on equality, universal public services, equity of access, sufficiency, sustainability. Better ideas are fortunately available for an alternative paradigm of sustainable social economy within ecological responsibility. We now have a rich contemporary discourse, to which scholars such as Ian Gough,1 Mariana Mazzucato,2 Sylvia Walby,3 Kate Raworth4 and others are contributing; scholars who advance progressive alternatives to our destructive, failed paradigm. The regular contributions to Social Europe from such scholars and so many others offer opportunities for a necessary discourse. Such scholarship indicates that we are neither at the end of history or of ideas, to reference the hubristic construct of Francis Fukuyama.5

Out of respect for those who have suffered greatly, those who have lost their lives, and indeed the bereaved families, we must not drift into some notion that we can recover what we had previously as a sufficient resolution, nor can we revert to the insecurity of where we were before, through mere adjustment of fiscal- and monetary-policy parameters. That would be so wholly insufficient to the task now at hand. A brighter horizon of opportunity must emerge, one which offers hope.

It is not only the case that the COVID-19 pandemic provides us with an opportunity to do things better; it also enables us to realize what is destructive of social cohesion and the environment. We must have the courage to examine critically the assumptions that brought us to this point. This crisis will pass eventually, but there will be other viruses and other crises. We cannot allow ourselves to be in the same vulnerable position again. On the most basic level, we should recover and strengthen instincts of moral courage we may have suppressed, which the lure of individualism may have driven out, displacing a sense of the collective, of shared solidarity, allowing the state’s value and contribution to be derided and disregarded, so that a narrow agenda of accumulation could be pursued.

We have to ask, too, if that narrow furrow which we ploughed for our teaching of economics has brought us to sources of policy based on abstract ideological assumptions rather than those transparent or open to empirical verification, and, thus, to a culpable incompetence, inability, and a confused silence, rather than a wide understanding of economics and the policies that might flow from it. We must, from now surely, do things in a different, in a more responsible and integrated way.

As well as highlighting the unequivocal case for a new form of political economy based on ecological and social sustainability, the pandemic has also demonstrated, I suggest, the critical importance of having universal basic services that will protect us in the future, as Anna Coote and Andrew Percy6 have suggested, and of enabling people to have a sufficiency of what they need, as Ian Gough has contended.7

In these speeches, I have sought to place global solidarity at the core of our new paradigm if we are to avoid healthcare collapse in many developing countries, including in sub-Saharan Africa. COVID-19 has all but halted migration as countries across the globe close borders, severely restricting mobility. This has implications for those seeking asylum, fleeing persecution and conflict. Such individuals are particularly at risk to COVID-19 because they often have limited access to water, sanitation systems and health facilities. I have written that we must ensure that people forced to flee are included in preparation and response plans for COVID-19.8

In these pieces, I have felt it necessary to repeat some, as I see it, essential messages. For example, we require enhanced attempts at the global level to build a new international architecture, to reverse the policy of fragmentation and institutional damage that has, in recent years, affected the United Nations and other multilateral organizations.

In all of Europe, transformative actions are now required. Good work is underway. For example, analysis by Ireland’s National Economic and Social Council (NESC) published in 2020 provides a framework within which the transition to a new political economy may be a just transition.9 This will require social dialogue and a deliberative process, as NESC suggests, which should be framed in the wider context of discussions on how we embed the just economy and society now so urgently needed and desired by the citizenry.

Successful crisis management is no guarantee of durable reform. We must turn the hard-earned wisdom from this crisis into strong scholarly work that can inform policy and institutional frameworks – this is the great challenge from a political-economy perspective.

There are great sources from which we are yet to adequately draw. For example, culture – the resource of ideas that are available in literary imagination, art, music and literature specifically – is rarely articulated in considerations as to the future of Europe. Yet words matter: words such as the declaration which called for a European Union. Now language and culture are underutilized, even neglected. This is a neglect for which the European Union has paid a heavy price. It is so reflected in the language of spokespersons who read minima to an anonymous citizen, but who achieve merely an echo of what on the European Street is perceived as not only insufficient but as inauthentic. As I write, cultural practitioners have been among the most impacted in terms of income and practice as a result of COVID-19, and we must all – governments and concerned citizens – show our solidarity by helping our writers and artists through this difficult time.

The scale of the change that is now required is, to my mind, similar to that which occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s in Central and Eastern Europe, an invocation of a moral future of peace similar perhaps in scale, scope and significance to that advocated in the Ventotene Manifesto in its day by Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi.10

Our challenge now is surely to draw on the best of indomitable instincts of solidarity and ingenuity as COVID-19 confronts 21st-century society and its world economy with a new kind of emergency hazard. We must galvanize those sentiments across the citizenries of the globe, invite a discussion on the inherent flaws of our current model, and create the capacities needed for embracing a new paradigm founded on universalism, sustainability and equality.

Looking ahead, my vision, of which I continue to write and speak as I try to avoid any Adornoesque pessimism, is of a Europe with quality public services at its core and decent jobs in the public sector. We must remember that the services the public sector delivers are not a cost to society, but an investment in our communities. This message must be taken to, and accepted in, the heart of Europe. It can help restore credibility and build a partnership with the European Street and its discourse. The ‘unaccountable’ – speculative flows of insatiable capital, a global, unregulated, financialized version of economy – represents the greatest threat to democracy, the greatest source of an inevitable conflict, and the greatest obstacle to us achieving an end to global poverty or achieving sustainability.

The lessons of necessity and solidarity learnt during the pandemic must now inform a European-led transition to a just and ecologically sustainable society in its aftermath. I am hopeful that, within an enlightened eco-social framework, we may respond together in a transformative, inclusive way to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, the impact of digitalization, rising inequality and the unaccountable, and, in doing so, address the democratic crisis facing so many societies in Europe and beyond.

May I express, as I did in my previous collection, When Ideas Matter, my deepest appreciation and thanks to those who helped me prepare speeches, as well as to the editors, Joachim Fischer and Fergal Lenehan, the translators and the publishers who are making this publication possible, and to the readers and students who I hope will elaborate, contest, improve and even apply its messages.

Michael D. Higgins, Uachtarán na hÉireann

December 2020

1.See, for example, Ian Gough,Heat, Greed and Human Need: Climate Change, Capitalism and Sustainable Wellbeing. Cheltenham,UKand Northampton,MA: Edward Elgar, 2017.

2.See, for example, Mariana Mazzucato,The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy. New York: Public Affairs, 2018.

3.See, for example, Sylvia Walby,Crisis. Cambridge, UK and Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2015.

4.See, for example, Kate Raworth,Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. White River Junction,VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2017.

5.Francis Fukuyama,The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press, 1991.

6.Anna Coote and Andrew Percy,The Case for Universal Basic Services. London: Polity Press, 2020.

7.Ian Gough,op. cit.

8.Michael D. Higgins, ‘Out of the tragedy of coronavirus may come hope of a more just society’.Social Europe, 22 April 2020. https://www.socialeurope.eu/out-of-the-tragedy-of-coronavirus-may-come-hope-of-a-more-just-society, 24 August 2020; and Michael D. Higgins, ‘We cannot ignore the impact of Covid-19 on Africa’,Irish Times, 23 April 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/michael-d-higgins-we-cannot-ignore-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-africa-1.4235431, 24 August 2020.

9.National Economic and Social Council Report, ‘Addressing Employment Vulnerability as Part of a Just Transition in Ireland’. Dublin:NESC, 2020. https://www.nesc.ie/publications, 24 August 2020.

10.Altiero Spinelli and Ernesto Rossi,The Ventotene Manifesto. https://www.federalists.eu/uef/library/books/the-ventotene-manifesto, 10 July 2020.

Introduction

the brexit shock

The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union has resulted in the resurgence of the political slogan upon Ireland’s neighbouring island. Thus we have had, for example, ‘Brexit means Brexit,’ while the need to ‘get Brexit done’ probably won an election in late 2019. As the material and geopolitical consequences of Brexit become clearer, however, the catchy slogans have all but dried up. For many in the European Union the Brexit referendum of June 2016 has acted as a wake-up call; for political and economic leaders, as well as for parliamentarians and civil society. The realization has dawned on many that the multilateral values taken for granted in western Europe since 1945 are not necessarily written in stone, that in the face of the utter ignorance and disconnect all too evident in the UK a lot more needs to be undertaken to engage citizens with the European Union, which is still essentially an unfinished political project. It has led to a new focus upon the social aspect of the Union and renewed vigour to engage citizens in the debate of where the EU, and its integration project, may feasibly go. Under Jean-Claude Juncker, on 1 March 2017, the White Paper on the Future of Europe was published starting a process of public debates in all Member States, with a preliminary end before the parliamentary elections in June 2019. In April 2017 the reflection paper on the noticeably more citizen-focused social dimension of Europe appeared followed by the Social Summit for Fair Jobs and Growth in Gothenburg in November 2017.

In Ireland also the debate about the European Union, and Ireland’s place within it, is gathering pace, and may be seen as branching out beyond the narrowly political, economic or fiscal aspects traditionally dominating commentary. Never before has the European Union been so present in the Irish media as it has been since 2016. Alongside the public arena major European policy initiatives have been engaged upon by the Irish government, beyond the immediate actions required by Brexit, with strategy papers taking a noticeably broader view than the traditional, often myopic, utilitarian focus, as evidenced by those dealing with Ireland’s relations with key EU Member States, such as Ireland in Germany: A Wider and Deeper Footprint (2018), a year later supplemented by Global Ireland: Ireland’s Strategy for France 2019–2025: Together in Spirit and Action. Both contain a strong cultural dimension and the acknowledgment that wider knowledge of European cultures and other EU languages are key to participating more fully in EU-wide discourses. The policy document Languages Connect: Ireland’s Strategy for Foreign Languages, 2017–2026 demonstrates – after a decade-long evasion of the issue of a languages strategy – a new urgency within the Department of Education and Skills, no doubt strongly encouraged by business and industry concerned about language shortages in the new economic environment. There is a clear consciousness that Ireland will have to connect to the EU and continental Member States much more intensely and directly post-Brexit, both in a material, i.e. economic, and an immaterial, i.e. political and intellectual sense.

The new context explains why the speeches of Ireland’s Head of State and President Michael D. Higgins since 2016 have become ever more European in outlook. But they not only echo the renewed interest in Europe, they also critically reflect upon the past, present and future of the European Union, and on what may have been missing in this debate, not only in Ireland. Whether it in fact reaches the ‘European Street’ is one of the key questions asked in these interventions. Undeniably, this is an appropriate time to present the President’s collected speeches in the accessible format of a book; a further contribution to the renewed European-wide interest in the future of Europe and the EU.

Some speeches in this volume were delivered within the wider context of Future of Europe Citizens’ Debates.1 Similarly to their fellow EU citizens, members of the Irish public also participated in several day-long national Citizens’ Consultations on the Future of Europe in Dublin and elsewhere, between November 2017 and May 2018. The final report of the Citizens’ Consultations of November 2018 states: ‘the abiding message was that the Irish people see Europe at the heart of their future and Ireland at the heart of Europe’.2 This bold statement might serve as a starting point for a brief review of Irish public discourses regarding Europe since joining the EU in 1973.

irish public discourses on europe

In the most recent Eurobarometer survey (no. 92) conducted in November 2019, Ireland had the most positive image of the European Union of all Member States. For 63 per cent of Irish respondents the EU conjured up positive associations. Only 7 per cent had a negative image, with 29 per cent retaining a neutral stance.3 The highest percentage in all of the EU Member States again (73 per cent) saw themselves as satisfied with the way democracy works in the EU, while only 17 per cent (again the lowest figure) expressed their unhappiness in this regard. No doubt these results are influenced by recent events in the context of Brexit and the EU’s substantial support for the Irish position, in which the Union centred Irish concerns in relation to the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement and the maintenance of an open border on the island. There is widespread confidence that whatever Brexit settlement is eventually arrived upon, significant EU support for Ireland, as the country most directly exposed to the fallout from the British decision of 2016, will be forthcoming. It should indeed not be a surprise if the approval ratings were to climb further as the economic consequences of COVID-19 become more obvious and Ireland, like all Member States, will for the foreseeable future become dependent on massive financial support underwritten eventually by the European Central Bank and the EU.

We are obviously in a new phase of Ireland’s membership of the European Union, one in which the fortunes of the country have become intertwined with that of the Union as a whole to an unprecedented level. In terms of approval ratings we are approaching the situation at the very commencement of membership when, in May 1972, 83 per cent voted for entry into the then European Economic Community. In the standard work on the subject (sadly somewhat out of date at this stage), Brigid Laffan and Jane O’Mahony identify three distinct phases in Ireland’s membership of the EU, and its predecessors, up to 2008.4 Phase I from 1973 to 1986 they regard as an adjustment phase characterized by what the authors call a ‘begging-bowl mentality’, while Phase II from 1986 they view as an increasing integration phase hastened by the economic crisis of the late 1980s. The third phase encompasses economic recovery and the accelerating boom of the so-called Celtic Tiger, and with this a more sceptical attitude towards the EU. This found expression in the now infamous Boston vs Berlin speech of then Tánaiste Mary Harney of 20005 (on which more below) and the two rejected referenda of Nice and Lisbon (though reversed in the subsequent years, in both cases). We can readily add two more recent phases following the appearance of Laffan and O’Mahony’s 2008 book: the bailout/austerity phase of 2009–16, while Brexit marks the beginning of the present phase, which is the one primarily reflected in this volume.

Ireland has been, indeed, a very active and committed member of the European Union. It has played a key role in some of the most momentous developments within the EU. These include – during the EU Council presidency from January to June 1990 – the facilitation of the easy accession of the former East Germany (much appreciated by Helmut Kohl’s German Government) and, during another presidency from January to June 2004, the welcoming of ten new members into the EU, mostly from the former Soviet bloc. Ireland has also supplied key EU politicians such as the late former Commissioner Peter Sutherland and the former President of the European Parliament Pat Cox; there are indications that the former European Parliament’s First Vice President and now Commissioner Máiréad McGuinness may become an even more influential Irish politician in Brussels. They are complemented by key figures in past EU administrations, such as Catherine Day and David O’Sullivan as well as the impressive and influential European Ombudsman, Emily O’Reilly. Maura Adshead has rightly judged that ‘considering its small population, Ireland has enjoyed disproportionate influence in the European Union’.6

The figures mentioned at the outset point – relatively speaking – to a generally positive and unambiguous relationship between the EU and Ireland in recent years. But it is also true to say that much of this support may be seen as somewhat shallow and based upon utilitarian motives and, therefore, may actually be quickly lost; as transpired in the early 2000s when Irish citizens rejected the EU’s agreed political position on two occasions, or indeed when strictures were imposed upon citizens – rather than bondholders – during the bailout phase. This may also be the outcome of a relatively narrow and superficial public discourse on the European Union, often confined to economics and lacking in any great critical depth. In particular the broader objectives of the European Union as a response to two world wars, the meaning of European citizenship, the future of the Union – including the concept of its finalité – and the necessary institutional changes required for its more effective functioning have received little sustained public debate. As in many other Member States, the debate about Europe and its future has remained a largely elite discourse, closed off from general citizens on the ‘European Street’; the small number of participants in the Citizens’ Consultations, while very welcome, did not fundamentally change the overall picture.

This has not been helped by the low priority the European Union and the concept of European citizenship has within the Irish education system. Quite rightly the results emanating from the Citizens’ Consultations unequivocally highlight this issue: ‘Education was seen as key.’7 Even though Ireland joined in 1973 it took more than forty years for an appropriate space to be created for EU Studies in the Politics and Society Leaving Certificate curriculum, first examined in 2018.8 There is widespread ignorance not only concerning the political structure of the EU and its institutions, but also around the distribution of competencies (the principle of subsidiarity). As a result the EU, often backed by national politicians, is regularly blamed for decisions which are in fact national responsibilities, or which the government itself had first formally agreed to in Brussels. In this regard, Ireland is no different to other Member States.

From a party-political perspective Irish discourses on the European Union, constructive ones at least, have been particularly closely related to the Fine Gael party. It very easily and quickly after Ireland’s accession found a political home in the European People’s Party, the European Parliament’s largest political grouping whose constituent parties have many heads of government in their midst, not least Angela Merkel and her predecessor as German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl. Fine Gael and the European People’s Party generally retain conservative and pragmatic positions favouring a smooth running of the capitalist market economy, seeing the EU as a facilitator of the existent order. Parties with a strong nationalist element in their ideological core, such as Sinn Féin, have always struggled with the concept of shared sovereignty. The left has, to a significant degree, marginalized itself within constructive public EU discourse, even if members of the Labour Party have been influential figures at European level, such as the long-standing MEP Proinsias de Rossa, the Irish member of the European Court of Auditors, Barry Desmond, or the co-founder (1989) of the Institute of European Affairs (now the Institute for International and European Affairs), the late Brendan Halligan.9 At the more extreme end of the political spectrum on the left we can also find Eurosceptic condemnation of the EU as a capitalist, neo-liberal and at times even neocolonial venture. For a while strongly Euro-critical positions were also held within the Labour Party, indeed also by Michael D. Higgins himself: in the 1980s, as the largely ceremonial but influential Chairman of the Labour Party he belonged to the radical left wing of the party and actively campaigned against the Single European Act of 1987 and the Maastricht Treaty on the basis of Irish neutrality.10 And yet, those who read (or remember) his statements from that period11 will still find in the present speeches more evidence of the values-based consistency of a socialist rather than an ideological flexibility indebted to age or office held. Higgins’ argument against the Maastricht Treaty was also the low priority and dilution the social dimension was accorded in that document; the speeches presented here prove that it has remained a key concern of his.12 This is also, of course, for readers themselves to judge. It is true to say that outside of President Higgins’ articles and speeches there have been few attempts by Irish intellectuals to popularize a constructive left-wing European position, which has for many years crystallized around the concept of a social Europe. We will pay particular attention to this here.

continental european debates

Closely related to Brexit, the evident resurgence of nationalism has also been a major issue for public intellectuals engaging with Europe, with some seeing this as endangering the European Union itself.13 Indeed, dealing internally with the increased nationalism of Union members, such as Poland and Hungary, may well be the most important EU question of future years. More recently the Bulgarian commentator Ivan Krastev has actually taken a benign view on the neo-nationalism of Brexit, which he does not see as an existential threat to the Union. In the 2020 edition of his publication After Europe he writes: ‘But if there is one single factor that is most responsible for Europe making its peace with the idea of maintaining the Union in some form, it is Brexit. Since 2016, Great Britain has been transformed in almost unimaginable ways. It has become provincial, disoriented, and unimportant.’14

In his recent pandemic book, Is It Tomorrow, Yet? How the Pandemic Changes Europe, Krastev argues that COVID-19 could actually lead to the consolidation and further integration of the European Union, as the global pandemic shows the necessity for both international cooperation and, at least partial, de-globalization.15

Indeed, the surge in nationalism in Europe has also resulted in the creation of a number of grassroots pro-EU movements from the ‘European Street’, which see themselves as inherently anti-nationalist. Trans-continental pro-European movements – with a defined and large social media presence and which organize pro-European events and demonstrations – include Pulse of Europe, the Young European Collective, the Democracy in Europe Movement 25 (DiEM25), We Are Europe and Stand Up for Europe.16 These movements are not uniform. For example, Pulse of Europe, which organized large pro-EU demonstrations throughout the continent following Brexit in 2016 and 2017, sees itself as reacting to radicalism and chooses not to identify as left or right; DiEM25, on the other hand, would like to reform the EU and sees post-capitalism and a new Green Deal as necessarily central to this; Stand Up for Europe sees a federal Europe, with a president, government and a shared budget, as their ultimate goal. While it is probably easy to criticize such movements as broadly liberal and middle class, it is also undeniable that there have been distinct stirrings upon the ‘European Street’, although substantially less so in Ireland, where the rather mainstream European Movement still remains the prime forum for civic engagement.

The political scientist Claus Leggewie has catalogued many of these grassroots movements in his book Europa Zuerst! (Europe First!). He sees these organizations as a direct reaction to increased nationalism and authoritarianism and, if Stalin were the midwife of a European Community post-1945, then Trump and Putin may conversely be seen as preparing the ground for a European Renaissance, Leggewie believes.17 He views these movements as agents of change that are joined together by an emphasis on democratic participation, solidarity and social and ecological sustainability; each group engages with a transnational problem central to the further development of wider European democracy. Leggewie includes in his discussion, for example, the Romanian anti-corruption movement that resulted in large demonstrations against the Romanian government in 2016; an association in Hungary that works with the Roma in direct confrontation with Viktor Orbán’s government; the Irish marriage equality movement preceding the referendum of 2015, of European importance within the context of increased homophobia within and outside of Europe; Polish women’s rights demonstrators protesting against their government’s increased social conservatism; the large number of pro-cycling associations attached to the European Cyclists’ Federation; Green economy campaigners in Greece; supporters of a universal basic income in Switzerland whose initiative resulted in a state-wide referendum; and academics in France looking for a more honest engagement with French colonialism.18

What is the connection between such movements and the European Union, beyond a general if perhaps vague idea of internationalist solidarity? Some of these groupings were financed by the European Union, others draw on the EU as a source of symbolic liberal-democratic support, or see it as an historical and institutional source of genuine social liberalization, as well as an organization symbolizing a more honest and balanced engagement with a dark past.

There is a particularly vibrant European debate, especially since 2016, in the German-speaking lands. These include more radical – even utopian – visions of a Europe of the future, such as that of the German political scientist Ulrike Guérot who has called for the creation of a new European Republic, in which the people hold sovereignty, with regions and cities as the foremost political agents.19 Far too little is known in the anglophone world, and in Ireland specifically, of such visions, although English-language translations of key works are readily available.20 One does not have to agree with such arguments – in fact in Guérot’s homeland few probably do – but her ideas are stimulating and worth discussing. Together with her Austrian collaborator, the writer Robert Menasse, Guérot has also co-authored a manifesto for a European Republic. Menasse has argued for the creation of a new, post-national democracy beyond the nation state. He has also published the award-winning novel Die Hauptstadt, translated into English as The Capital and often hailed as the first EU novel, in which one of the characters makes a startling proposal for the relocation of the EU capital.21 The novel is evidence of a broadening discourse, of a branching out into the cultural and literary field, and thus precisely in the direction Michael D. Higgins advocates in his speeches. France has contributed the more applicable, though equally radical, anti-capitalist proposal by Stéphanie Hennette, Thomas Piketty and others.22 Otherwise, beyond President Macron’s European initiatives (acknowledged by President Higgins), France appears to be, to outside observers at least, too absorbed in internal political struggles to continue the vibrant debate of previous decades, with Edgar Morin’s Penser l’Europe (1987) being the outstanding example of this earlier engagement with the concept of Europe.

ireland and intellectuals

What about Irish contributions to this debate? Is it possible that ‘continental countries’, albeit to varying degrees in respective societies, still admire and live the tradition of intellectuals more in an age that is increasingly losing respect for intellectual work? Before we examine Irish thoughts on Europe some reflections upon the particular role of intellectuals are appropriate here, not least as President Higgins has always been viewed in his home country as the quintessential Irish public intellectual. What exactly a public intellectual is, however, remains open to debate. Mary Corcoran sees a public intellectual as having a bridging function between academia and the general public; the political scientist Tom Garvin sees the purpose of the public intellectual as one of encouraging a wider audience to think; while the sociologist Pat O’Connor sees the role as ‘creating new agendas and raising issues those in power currently wish to avoid’.23 The post-colonial theorist Edward Said perceives the public intellectual as challenging ‘both an imposed silence and the normalised quiet of unseen power’.24 The German literary scholar Heinz Drügh views public intellectuals as formulating concepts and ideas that are inherently abstract and have not taken material or physical form yet, while personal popularity is also unavoidable for the more successful of the type.25 All of these views retain a degree of validity, making any ‘mapping’ of the landscape of public intellectualism a somewhat onerous task.

The question might be asked, is Ireland an unwelcoming place for intellectuals? Describing twentieth-century Britain, Stefan Collini has written of the hostility towards the figure of the intellectual, of how the intellectual has often been conceived as essentially other; a figure of other societies and other ages, not the here and now.26 Many would probably argue that this view is also relevant for Britain’s neighbouring island: is intellectualism not seen as an element of the distant Yeatsian past? Something that takes place somewhere else, in Paris perhaps? Ireland no longer now has what can be described as a dedicated journal of ideas. The Irish Review valiantly struggled to replace the formidable Crane Bag since the mid-1980s when the latter ceased publication, eventually succumbing to market pressures in early 2020. Indeed Irish culture has been notably chided for its perceived anti-intellectualism. Historian Joe Lee has memorably stated that twentieth-century Irish culture is ‘more sub-intellectual’ than anti-intellectual, as ‘anti-intellectualism is too intellectually demanding’; the sociologist Mary Corcoran has also more recently argued that Ireland is becoming increasingly anti-intellectual.27 Indeed, while the Irish literary imagination has been extremely well researched by Irish and international academics, Irish intellectual history and culture has received, comparatively, scant attention.28

Perhaps paradoxically then, Michael D. Higgins has made the public communication of complex and abstract ideas central to his presidency. He has also been a president of unprecedented popularity, not least among younger people.29 Should we, thus, actually talk about ‘subtle-intellectualism’ rather than sub-intellectualism within contemporary Irish culture? Certainly the Irish landscape of public intellectuals is now complex and diverse, while communication itself takes place among a variety of media. Public intellectuals are more likely to communicate via social media, podcasts or recently established websites, rather than traditional print media or RTÉ television. Indeed, the webzine the Dublin Review of Books, which publishes long-form argumentative essays usually based upon recent publications, lists up to 600 contributors, mostly Irish or Irish-based, suggesting that any lingering idea of Irish anti-intellectualism is an historical rather than contemporary reality.30 While academic commentators have often suggested that a strong male gendering of public intellectualism in Ireland is evident,31 this has probably become less defined.

The sociologist Liam O’Dowd suggests that in Ireland ‘the contested nature of nation- and state-building and the lack of congruence between state and nation have ensured a political prominence for public intellectuals who narrate the “national story” or the “national-predicament”’.32 The ‘national’ certainly remains the dominant frame of reference for intellectual debate, whether in relation, for example, to discussion concerning the past or contemporary feelings of belonging.33 President Higgins’ reflections on the concept of ‘home’ respond, at least partly, to this national narrative. But, in contrast to the dominant discourse, he has always gone beyond it, to Europe and the wider world.

irish intellectuals and europe

While political scientists and political sociologists who specialize in the transnational European Union, such as Brigid Laffan and Katy Hayward, have had an undoubted wider presence in recent public intellectual life, much of the post-Brexit commentary has dealt with Ireland and Britain rather than an abstract or visionary idea of Europe itself.34 Indeed, Fintan O’Toole – probably the best-known Irish public intellectual in the wider English-speaking world – has journeyed in recent years from incisively analysing Irish culture and politics to de-robing the pomposities of Brexit Britain and Trump’s America; remaining distinctly however within a national frame of reference, even if the nations he deals with have changed in a fundamental fashion.35 Michael D. Higgins is the sole contemporary public intellectual to regularly engage with an abstract idea of an alternative European space; the sole Irish intellectual looking to consistently reimagine Europe.

This is not to say, of course, that Irish intellectuals have ignored the topic. Katy Hayward has argued that Irish visionary engagement with Europe has largely taken place within the dominant conceptual frameworks of Catholicism and nationalism.36 In the 1940s Seán Ó Faoláin and Hubert Butler argued in favour of a future European federation that would enhance Irish nationhood as Ireland could engage with other small nations, while social democrat and constitutional Irish nationalist John Hume in the 1980s looked to a realigned European federal space within a new Europe of the Regions.37 Examining Irish state discourse during the first thirty years of EEC/EU membership, Hayward also contends that ‘a symbiotic relationship between national and supra-national ideologies’ has existed; the language of Europe has simply been incorporated into the language of constitutional Irish nationalism, she convincingly argues.38 Drawing on anarchist thought and postmodern theory, the philosopher Richard Kearney also looked to reimagine European space in the 1980s and early 1990s, although his thinking often tended towards an ambivalently defined united Ireland within Europe and, thus, also remains within the general framework of constitutional nationalism.39

Michael D. Higgins’ writings on Europe largely exist outside of these nationalistic paradigms. The wider intellectual context within which to situate his writing and speeches on Europe – based as it is upon a transnational vision beyond capitalism – is actually within a left-oriented Social Europeanism, which has had, otherwise, little purchase in Ireland (as the Labour Party found out during the European election campaign of 2019). The philosophical core of this position can be found in the writings of Jürgen Habermas. Michael D. Higgins could indeed be described as an Irish Habermassian; the work of the German philosopher permeates his thought, as is clearly evident from the present collection. Habermas’ Social Europeanism is based upon a number of consistent ideas: the need for post-nationalist government beyond the nation state, secularization, a belief in the management potential of the state in economics and the necessity for a strong solidarity-orientation within society.40 The most significant argument, for Habermas, in favour of greater European integration is the fact that an unwieldy, globalized form of capitalism, which can very easily go beyond borders, requires an effective transnational institution to act as a controlling mechanism and which also functions beyond the confines of the nation state.41 The website www.socialeurope.eu42 brings together a number of contemporary authors, many inspired by Habermas, who write from a Social Europeanist perspective on issues such as inequality, the future of work, just transition, the refugee crisis and rising populism.43

reclaiming the european street

The present volume should be seen within this wider European context; President Higgins’ frequent reference to continental political thinkers and philosophers is no coincidence. His is an Irish contribution to the Europe-wide debate concerning the future of Europe, arguably the first of its kind. It intends to invigorate and broaden the debate, but retains a clear direction and focus.

President Michael D. Higgins’ political home is the Labour Party. The vision of the European Union developed here is that of a social Europe founded on values; an ethical union, which places citizens and workers – and specifically the materially disadvantaged – at the centre of the EU’s concern. It is a vision that is critical of globalized, financialized capitalism and neo-liberalism, which, these speeches make clear, have also been adopted by EU policymakers and integrated into European treaties, such as that of Lisbon. But rather than arriving at a Eurosceptic conclusion, the speeches return to the founding documents of the European integration project, the Ventotene Manifesto and the Treaty of Rome. The speeches are to be read as examples of a left-wing pro-European constructive criticism. The vision of a sustainable economy echoes the objective of the European Green Deal, the centrepiece of the new Commission’s work plan. President Higgins’ vision is also a gendered vision within which women are not just given equal rights but where the ‘female’ values of community, communication and cooperation move close to the centre.44 The title of the volume is deliberately ambivalent: it highlights the need to engage with the ‘street’ while also critiquing the violence stirred by nationalist populist agitators and the ideologues articulating themselves there; the latter is seen as a result of the failure of the former. The streets of Europe need to be reclaimed from the dangers and vanities of populist nationalism. Advocates of socially and ecologically aware internationalism need to make their arguments more forcefully.

Irish discourses concerning the European Union are often characterized by their complete exclusion of the cultural dimension. President Higgins regularly makes a point of including and quoting European writers and philosophers, from Aristotle to Friedrich Schiller and Czesław Miłosz. A poet himself, he aims to integrate the imaginative and utopian dimensions integral to art and literature into the European discourse. This not only broadens the debate and makes it more future-oriented rather than pragmatic and present-focused, it also adds colour, vibrancy and excitement to an EU discussion that has tended towards the stale and dreary, where legal, economic and often distant political aspects predominate.

Linked to this is the linguistic dimension. A fluent speaker of Irish, President Higgins also connects the language question to the European discourse, including lesser-used languages as expressions of minorities and marginalized communities. He emphasizes linguistic and cultural diversity and its preservation as an integral part of the Union’s identity, a value which native speakers of the EU’s effective lingua franca English often only insufficiently acknowledge. Its corollary is that an openness towards Europe cannot be achieved without a positive attitude towards learning its languages. Irish citizens decrying the distance of Brussels from their everyday lives rarely reflect upon the added distance the language of the Brussels administration creates for other citizens in the EU, 98.5 per cent of whom post-Brexit speak another language as their native tongue.

President Higgins’ speeches also proudly describe the European intellectual heritage and its influence globally in terms of political and philosophical traditions, specifically in terms of human rights and democratic principles emanating from the Enlightenment period. These are also placed in more specific national contexts in the speeches on Ireland’s cultural relations with individual Member States, where both parties remain part of broader European traditions of thought. The regular references to recent and contemporary continental thinkers and intellectuals, be they Paul Ricoeur, Jürgen Habermas, Wolfgang Streeck or Hartmut Rosa, mean that these speeches must be seen as part of a continent-wide European conversation, continuing in a fashion the tradition of Humanists from all of Europe corresponding with Erasmus of Rotterdam. This highlights a tension that the author is very well aware of. One could argue that this volume by an unashamedly public intellectual continues the elitist discourse on Europe; this would however be utterly misreading its thrust. The constant insistence on practical application and implementation in terms of social policy is only one aspect: the conviction that philosophy concerns itself with ethics and values is another. In this sense, thinking philosophically about Europe serves a very practical and social purpose, and ultimately aims to improve the lives of all citizens.

the present edition

This volume contains twenty-three speeches grouped into five sections plus a Postscript on COVID-19, taking the collection right up to present concerns. It brings together all of President Higgins’ major speeches on the topic of Europe since 2016.

As already stated, the Brexit decision in the UK has fundamentally altered Ireland’s relationship with the European Union, and has exponentially increased interest in European matters in public debates in this country. But there are also other reasons for choosing the start date of 2016. The Centenary celebrations of the Easter Rising offered an opportunity to reflect upon the European dimension in Irish history. The role and function of historical memory is an issue President Higgins addresses frequently; its European dimension provides the theme for the first group of speeches. The start date of 1 January 2016 is also to avoid any overlap and repetition with an edition of President Higgins’ speeches with a far wider remit entitled When Ideas Matter, which appeared in 2017.

The volume encompasses interventions on historical aspects, bilateral cultural links, citizens’ involvement in the European project, workers’ rights, trade unionism, third-level education and ecological concerns. A long-standing campaigner for human rights on behalf of the so-called ‘developing world’, President Higgins’ finishing speech focuses on the EU’s southern neighbours, reminding us that the EU has responsibilities for the wider world and especially for the continent of Africa, on which it may very well depend for its long-term future. That Europe is the first destination for refugees lends immediate urgency to the issue. The question of migration is presented as a consequence of global inequality and the speech reiterates the point that politics is, ultimately, a moral and ethical issue.

We also include three translations into Irish, French and German of three selected speeches. The translation into Irish responds to the President’s particular concern for Ireland’s first official language – due to be given full official status in Brussels in 2022 – which he showed during his tenure as Minister for Arts, Culture and the Gaeltacht 1994–97 when Teilifís na Gaeilge, now TG4, Ireland’s public Irish-language television channel, was established. The translations into French and German, the most widely spoken native languages in the EU and two of its three ‘procedural languages’ in which the Commission conducts its internal affairs (alongside English), highlight the multilingual nature of the European Union, but they are also included in order to increase the book’s international appeal. Despite the President’s active travel schedule (as evidenced by the venues mentioned in this book), little is known about Irish discourses on Europe, the EU and its future outside of Ireland. We hope that this volume will make an important contribution in this regard. As an intervention by Ireland’s First Citizen we hope it will meet with interest in Brussels, among European politicians and in leading intellectual circles and think-tanks in other Member States, perhaps even on the European Street.

Non-Irish readers may find it surprising that the volume contains little on arguably the two most frequently talked about Irish issues EU-wide since 2016: Northern Ireland and the country’s dogged defence of its taxation policy, specifically its corporation tax strategy. It must be openly acknowledged that what are presented here are the speeches of the Irish Head of State whose limits are narrowly defined by the Irish Constitution. The President of Ireland cannot, of course, openly interfere in (and much less criticize) government policy and the political process, even though President Higgins is well known for continuously testing the limits of his brief; this was perhaps the very reason why he was re-elected with a landslide majority. Rather than disappointment, we hope the volume may generate surprise about the trenchant criticism of neo-liberal capitalism expressed here, emerging from a country whose international stereotype is still infused with rurally-based conservative Catholicism. The speeches are a sign of a profound political change in Ireland which mirrors – but also deviates from – EU-wide trends.

It is well worth remembering that President Higgins was overwhelmingly re-elected in 2018 at a time of relative economic stability, a time usually not favourable to left-wing critics. This volume indicates an Ireland that has become more secular, open, critical and in party-political terms has noticeably shifted to the left. Recent elections, as in other EU countries, have seen a decline of the traditional (conservative) popular parties Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, from which the President’s original political home, the Irish Labour Party, has however not benefited: as in other Member States, decades of collaboration with a system which many voters regard as incapable of solving the problems of growing inequality and the erosion of workers’ rights, have taken their toll. That nearly half of Ireland’s MEPs elected in the last European election of 2019 are of a left or ecological left persuasion is an expression of the new political climate. The volume is a document of an Ireland in flux, a country on the periphery, yet even without Brexit well on its way to embracing EU political ‘normalcy’: not a few outsiders may be surprised to hear that the percentage of Ireland’s population not born in the state is actually higher than in Germany.

Lastly, the speeches highlight to what extent Irish culture has always been intertwined with that of other European countries and is, thus, very much part of the collective European heritage. Mary Harney’s statement that ‘geographically we are closer to Berlin than Boston … spiritually we are probably a lot closer to Boston than Berlin’ was questionable in 2000, and is arguably even more so now twenty years later.

Many of the speeches were first delivered to non-Irish audiences, and the key point in Michael D. Higgins’ speeches applies to all EU citizens. There is a need for all citizens of the EU to take a broader perspective and an ethical view of the European Union, a view that goes beyond our narrow individual and national needs and considers the ultimate purpose for which the European Union and its predecessors were established. Frequently President Higgins refers to the Ventotene Manifesto, its peaceful, internationalist and tolerant spirit centring on the improvement of citizens’ lives. Only when a united Europe – whatever its eventual political structure – becomes a project not only for but also of its citizens does the EU have a long-term future.

The speeches have been slightly edited but retain their flavour of oral delivery. Certain repetitions have been removed but some remain in order not to interfere with the integrity of the texts. We have also retained occasional passages in Irish as delivered on the occasion. English translations are given in footnotes.

We would like to thank President Higgins for suggesting the idea of this book to us following his state visit to Germany in 2019 and for granting us access to all of his speeches and additional notes. We would like to thank especially Claire Power, Adviser to the President, for her instant responses to all our enquiries and her help with the numerous photographs accompanying this edition. We are grateful to our three translators, Pádraig de Bhaldraithe, Dominique Le Meur and Rolf Höfig for delivering their translations within a very short timeframe. Our thanks are also due to Antony Farrell of The Lilliput Press for readily and enthusiastically engaging in the project and to the editorial team for bringing it through the editing stages in a timely fashion. All of us were keen to bring out this book as soon as possible as it responds to issues of the day. Lastly, we would like to acknowledge the financial support of the European Union’s Jean Monnet Programme as part of, arguably, the most successful programme the EU has ever undertaken, ERASMUS, now expanded into ERASMUS+. While many other programmes have generated rivalry and competition, ERASMUS has had, since 1987, no other purpose than bringing young people together, without whose involvement and engagement the EU has no future. It is thus quite appropriate that President Higgins should also highlight it in several instances in his speeches.

Joachim Fischer (Limerick)

Fergal Lenehan (Jena)

December 2020

1.The speeches in Florence and Kaunas in this volume, pp. 66–78, 150–9.

2.https://www.dfa.ie/our-role-policies/ireland-in-the-eu/future-of-europe/news/newsarchive/report-on-citizens-consultations-on-the-future-of-europe-in-ireland.php, 30 September 2020.

3.https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/STANDARD/surveyKy/2255, 7 September 2020.

4.Brigid Laffan und Jane O’Mahony,Ireland and the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, 30ff.

5.Mark Brennock, ‘Harney Opposed to Closer Integration of Europe’.Irish Times, 22 July 2000 https://www.irishtimes.com/news/harney-opposed-to-closer-integration-of-europe-1.295209, 21 January 2021.

6.Maura Adshead, ‘European Union Politics and Ireland’. In: Brian Lalor (ed.),The Encyclopedia of Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 2003, pp. 364–5.

7.‘Report on Citizens’ Consultations on the Future of Europe in Ireland’, p. 4. https://www.dfa.ie/our-role-policies/ireland-in-the-eu/future-of-europe/news/newsarchive/report-on-citizens-consultations-on-the-future-of-europe-in-ireland.php, 20 September 2020.

8.There is also some space available during the Junior Cycle within the Civil, Social & Political Education (CSPE) course.

9.Stephen Collins has meticulously documented the party’s dissensions on the issue of Europe. See: Stephen Collins, ‘Labour on Europe: from No to Yes’. In: Paul Daly et al. (eds),Making the Difference: The Irish Labour Party 1912–2012. Cork: Collins Press, 2012, pp. 154–64.

10.Irish Times, 14 May 1987;Irish Times, 20 May 1992.

11.See, for example, Michael D. Higgins, ‘Ireland in Europe 1992: Problems and Prospects for a Mutual Interdependency’. In: Richard Kearney (ed.),Across the Frontiers: Ireland in the 1990s Cultural-Political-Economic. Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1988, pp. 58–77.

12.Irish Times, 30 November 1991.

13.See, for example, Evelyn Roll,Wir sind Europa! Eine Streitschrift gegen den Nationalismus.Berlin: Ullstein, 2016.

14.Ivan Krastev,After Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2020, pp. 117–18.

15.Ivan Krastev,Ist heute schon morgen? Wie die Pandemie Europa verändert. Berlin: Ullstein, 2020, p. 28, pp. 74–7.

16.https://pulseofeurope.eu/en/; http://www.whoifnotus.eu/about/; https://diem25.org/about/; https://we-are-europe.org/en/events-and-campaigns/; and https://www.standupforeurope.org/about/our-mission, 28 July 2020.

17.Claus Leggewie,Europa Zuerst! Eine Unabhängigkeitserklärung. Berlin: Ullstein, 2017, p. 8.

18.Leggewie, pp. 212–66.

19.Ulrike Guérot, ‘Europe as a republic: the story of Europe in the twenty first century’.Open Democracy, 29 June 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/can-europe-make-it/europe-as-republic-story-of-europe-in-twenty-first-century, 23 July 2020. See also: Robert Menasse,Der europäsiche Landbote: Die Wut der Bürger und der Friede Europas.Vienna: Zsolnay, 2012.

20.Ulrike Guérot,Why Europe Should Become a Republic! A Political Utopia. Berlin: Dietz, 2019 (German orig. 2018).

21.See the review by Fintan O’Toole in theNew York Review of Books, 24 October 2019.

22.Stéphanie Hennette, Thomas Piketty, Guillaume Sacriste, Antoine Vauchez,How to Democratize Europe. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press, 2019.

23.See: Mary P. Corcoran, ‘Introduction: Challenging Intellectuals’ pp. 3–11, p. 4; Tom Garvin, ‘The Assault on Intellectualism in Irish Higher Education’, pp. 29–37, p. 31; and Pat O’Connor, ‘Reflections on the Public Intellectual’s Role in a Gendered Society’, pp. 55–73, p. 57. In: Mary P. Corcoran and Kevin Lalor (eds),Reflections on Crisis: The Role of the Public Intellectual. Dublin:RIA, 2012.

24.Edward W. Said, ‘The Public Role of Writers and Intellectuals’. In: Helen Small (ed.),The Public Intellectual. Oxford and Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2002, pp. 19–29, p. 31.

25.Heinz Drügh, ‘Pop-Intellektualität’. In: Jürgen Fohrmann and Carl Friedrich Gethmann (eds),Topographien von Intellektualität. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2018, pp. 58–81, p. 63, p. 64.

26.Stefan Collini, ‘“Every Fruit-Juice Drinker, Nudist, Sandal-Wearer…”: Intellectuals as Other People’. In: Helen Small (ed.),The Public Intellectual, pp. 203–23, p. 214.

27.J. J. Lee,Ireland 1912–1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge: University Press, 1989, p. 577, and Genevieve Carbery, ‘Ireland becoming anti-intellectual, academic editor says’.Irish Times, 28 June 2012. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/irelandbecoming-anti-intellectual-academic-editor-says-1.1069133, 7 July 2020.

28.For exceptions, see: Richard Kearney,The Irish Mind. Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1985; Thomas Duddy,A History of Irish Thought.London and New York: Routledge, 2002; Michael Brown,The Irish Enlightenment. Cambridge,MA: Harvard University Press, 2016; Bryan Fanning,The Quest for Modern Ireland: The Battle of Ideas 1912–1986. Dublin and Portland,OR: Irish Academic Press, 2008; Mary P. Corcoran and Kevin Lalor (eds),Reflections on Crisis: The Role of the Public Intellectual; Fergal Lenehan,Intellectuals and Europe: Imagining a Europe of the Regions in Twentieth-Century Germany,Britain and Ireland. Trier: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2014.

29.Dominic McGrath, ‘Millennials for Michael D: Why young people are backing a Higgins presidency’. https://www.thejournal.ie/millennials-and-michael-d-higgins-presidency-4257246-Sep2018/, 21 July 2020.

30.https://www.drb.ie/contributors, 22 July 2020.

31.Moynagh Sullivan, ‘Raising the Veil: Mystery, Myth and Melancholia in Irish Studies’. In: Patricia Coughlan and Tina O’Toole (eds),Irish Literature: Feminist Perspectives.Dublin: Carysfort Press, 2008, pp. 245–8, p. 246.

32.Liam O’Dowd, ‘Public Intellectuals and the “Crisis”: Accountability, Democracy and Market Fundamentalism’. In: Mary P. Corcoran and Kevin Lalor (eds),Reflections on Crisis, pp. 77–102, p. 88.

33.See, for example, Diarmuid Ferriter, ‘Commemorations need political leadership’.Irish Times, 18 January 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/diarmaid-ferriter-commemorations-need-political-leadership-1.4143053, 22 July 2020; and Emma Dabiri, ‘Let’s Talk about Race and Identity in Ireland’.Dublin Inquirer, 11 October 2017. https://www.dublininquirer.com/2017/10/11/emma-let-s-talk-about-race-and-identity-in-ireland, 22 July 2020.

34.See, for example, Brigid Laffan, ‘Ireland may have to sacrifice sacred cows to survive Brexit’.Irish Times, 16 May 2017. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/ireland-may-have-to-sacrifice-sacred-cows-to-survive-brexit-1.3083791, 22 July 2020; and Katy Hayward, ‘Northern Ireland may find itself between a rock and a hard place after Brexit’.Irish Times, 13 January 2020. https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/northern-ireland-may-find-itself-between-a-rock-and-a-hard-place-after-brexit-1.4137426, 22 July 2020.

35.See, for example, Fintan O’Toole,Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger. London: Faber & Faber, 2009; Fintan O’Toole,Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain. London: Head of Zeus, 2018; and Fintan O’Toole, ‘Unpresidented’.New York Review of Books, 23 July 2020. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2020/07/23/trump-unpresident-unredeemed-promise, 23 July 2020.

36.Katy Hayward, ‘From Visionary to Functionary: Representations of Irish Intellectuals in the debate on “Europe”’.Études irlandaises. 34/2, 2009, 87–100. https://journals.openedition.org/etudesirlandaises/1650, 23 July 2020.

37.Lenehan,Intellectuals and Europe, pp. 82–92, 117–18.

38.Katy Hayward,Irish Nationalism and European Integration: The Official Redefinition of the Island of Ireland. Manchester: University Press, 2009, p. 8.

39.Lenehan,Intellectuals and Europe, pp. 95–118. On the role of Europe and Europeanism in the field of Irish Studies, see Joachim Fischer, ‘Boston or Berlin? Reflections on a Topical Controversy, the Celtic Tiger and the World of Irish Studies’,Irish Review48. Summer 2014, 81–95.

40.Jürgen Habermas, ‘Der 15. Februar Oder: Was uns Europäer verbindet’. In: Habermas,Der gespaltene Westen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2004, pp. 43–51, here pp. 48–51.

41.Jürgen Habermas, ‘Drei Gründe für “Mehr Europa”’. In: Habermas,Im Sog der Technokratie. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2013, pp. 132–7, here pp. 133–4.

42.https://www.socialeurope.eu/ 24 July 2020. Colin Crouch,Social Europe: A Manifesto.Berlin: Social Europe Publishing, 2020 provides a good summary of the present state of the debate.

43.The social philosopher Oskar Negt and the trade unionist Tom Kehrbaum have also published texts that present, essentially, social democratic visions of Europe. Oskar Negt,Gesellschaftsentwurf Europa. Göttingen: Steidl, 2012; and Tom Kehrbaum, ‘Ein soziales und ein demokratisches Europa neu denken!’ In: Ulrike Guérot, Oskar Hegt, Tom Kehrbaum and Emanuel Herold,Europa jetzt! Eine Ermutigung. Göttingen: Steidl, 2018, pp. 11–38.

44.See, for example, the conclusion of the Leipzig speech.