9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

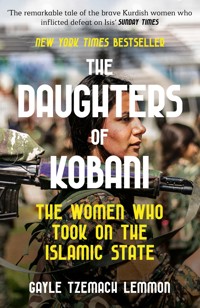

The extraordinary story of the women who took on the Islamic State and won In 2014, northeastern Syria might have been the last place you would expect to find a revolution centered on women's rights. But that year, an all-female militia faced off against ISIS in a little town few had ever heard of: Kobani. By then, the Islamic State had swept across vast swathes of the country, taking town after town and spreading terror as the civil war burned all around it. From that unlikely showdown in Kobani emerged a fighting force that would wage war against ISIS across northern Syria alongside the United States. In the process, these women would spread their own political vision, determined to make women's equality a reality by fighting - house by house, street by street, city by city - the men who bought and sold women. Based on years of on-the-ground reporting, The Daughters of Kobani is the unforgettable story of the women of the Kurdish militia that improbably became part of the world's best hope for stopping ISIS in Syria. Drawing from hundreds of hours of interviews, bestselling author Gayle Tzemach Lemmon introduces us to the women fighting on the front lines, determined to not only extinguish the terror of ISIS but also prove that women could lead in war and must enjoy equal rights come the peace. Rigorously reported and powerfully told, The Daughters of Kobani shines a light on a group of women intent on not only defeating the Islamic State on the battlefield but also changing women's lives in their corner of the Middle East and beyond.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 390

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ALSO BY GAYLE TZEMACH LEMMON

Ashley’s War

The Dressmaker of

Khair Khana

SWIFT PRESS

First published in the United States of America by Penguin Random House 2021 First published in Great Britain by Swift Press 2021

Copyright © GTL Group, Inc 2021

The right of Gayle Tzemach Lemmon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Map by Jeffrey L. Ward

Interior insert images: page 7, top and bottom: Getty/AFP Contributor; page 8, top: Getty/Delil Souleiman. All other images courtesy of the author.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781800750456

eISBN: 9781800750463

To Frances Spielman and Rhoda Spielman Tzemach, who taught me everything.

To Eli Tzemach, who taught me about pistachios, backgammon, the proper taste of watermelon, Marlboro Reds, and so much more.

And to all those women whose stories will never be told.

“The best revenge is not to be like your enemy.”

MARCUS AURELIUS,

Meditations

CONTENTS

MAP

AUTHOR’S NOTE

GUIDE TO THE STORY’S CHARACTERS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FURTHER READING

NOTES ON SOURCES

INDEX

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The stories in this book reflect three years of research and on-the-ground interviews across three countries. This includes seven reporting trips to northeastern Syria between 2017 and 2020, along with more than one hundred hours of interviews across the United States and in northern Iraq.

My focus has been to provide the most precise accounting possible of the history that follows. I have worked hard to ensure the accuracy of the dates, times, and narratives reconstructed in this story, including conversations between characters built from interviews with multiple people holding different perspectives.

Security in northeastern Syria evolved throughout this time, as did America’s presence in the area. Out of respect for the security and privacy of some who spoke with me, I have changed the names of several U.S.-based characters and omitted identifying details. For some people, including YPJ fighters, I have used only first names.

GUIDE TO THE STORY’S CHARACTERS

SYRIAN CHARACTERS

Nowruz: Women’s Protection Units commander

Rojda: Women’s Protection Units member

Azeema: Women’s Protection Units member

Znarin: Women’s Protection Units member

Mazlum Abdi: Head of the People’s Protection Units, later head of the Syrian Democratic Forces

Ilham Ahmed: Copresident of the Syrian Democratic Council

Fauzia Yusuf: Political leader

AMERICAN CHARACTERS

Mitch Harper: U.S. Special Operations

Leo James: U.S. Special Operations

Brady Fox: U.S. Special Operations

Jason Akin: U.S. Special Operations

Brett McGurk: Special presidential envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS

Amb. William Roebuck: Senior adviser to Special Presidential Envoy Brett McGurk; deputy special envoy to the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS

INTRODUCTION

I made the trip to the Iraqi-Syrian border with some reluctance. I told myself that I had given up war—at least for a bit. I felt deeply guilty that I enjoyed the luxury of making that choice while so many I had met in the past decade and a half did not, but I was homebound and determined to stay that way.

I had spent years telling stories from and about war. My first book, The Dressmaker of Khair Khana, introduced readers to a teenage girl whose living-room business supported her family and families around her neighborhood under the Taliban. During years of desperation, it created hope. I came to love Afghanistan—the strength and resilience and courage that I saw all around me and that rarely reached Americans back home. I wanted readers to know the young women I met who risked their lives each day fighting for their future.

The Dressmaker of Khair Khana led to my next story, Ashley’s War, about a team of young soldiers recruited for an all-female special operations team at a time when women were officially banned from ground combat. That book changed me, just as the first book had. Once more, the upheaval of war created openings for women. I felt personally responsible for bringing this history to as many readers as I could, given the grit and the heart of the women I met in the reporting process and their valor on the battlefield in Afghanistan.

The post-9/11 conflicts had come to shape my life: I got married only a few days before heading to Afghanistan for the first round of research for Dressmaker. I found out I was pregnant with my first child while in Afghanistan two years later, when I was finishing the book. For Ashley’s War, I spent years not long after my second pregnancy immersed in the workings of the special operations community, and I was in constant touch with a Gold Star family forever changed by their daughter’s deployment. They taught me what Memorial Day actually means.

I felt deeply proud of the work. And I also felt emotionally spent, trying to make Americans care about faraway places and people that meant so much to me personally. I was tired of living two lives, the one at home and the one immersed in war, and I thought often of that moment in the film The Hurt Locker when you return full of fervor to persuade Americans to care about their conflicts and then wind up in the grocery store, looking at stacks of cereal boxes on the shelf, and realize no one back home even remembers these wars remain under way.

I would recharge for a bit, I decided. Tell a story about the community of single moms who raised me.

And then I received a phone call that changed everything.

“Gayle, you have to see what’s happening here. I’m not joking—it’s unbelievable,” Cassie said when I picked up her call from a number I did not recognize one afternoon in early 2016. She was a member of an Army special operations team deployed to north-eastern Syria, where U.S.-backed forces were fighting the extremists of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. This was her third deployment. She had served in Iraq in 2010 as a military police officer. Then she signed up to go to Afghanistan in 2011 as part of the Cultural Support Teams, serving alongside the Seventy-Fifth Ranger Regiment; she belonged to the all-women’s team I chronicled in Ashley’s War. A few years after her Afghanistan tour, she joined Army Special Operations Forces, and that work led her to Syria and the ISIS fight.

Cassie told me that in Syria she had worked with women fighting ISIS on the front lines and that they had started a revolution for women’s rights. These women now were part of the U.S.’s partner force—the fighters the U.S. had aligned with to counter the Islamic State. These women followed the teachings of the jailed Turkish Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan, whose left-leaning ideology of grassroots democracy insisted that women must be equal for society to truly be free. They belonged to a group called the YPJ, the Kurdish Women’s Protection Units. Cassie explained that they had been fighting for the Kurds since the beginning of the ISIS battle and well before. How they led men and women alike in the fight. How their members had blown themselves up when it looked as if ISIS fighters would capture them. How they faced none of the restrictions American women confronted when they went to war—no rules about which jobs were open to them and which remained off-limits—and instead served as snipers and battlefield commanders and in a whole host of other frontline leadership roles. How they all shared the same messages and talking points about women’s equality and women’s rights, leading the Americans to consider them both incredibly effective leaders and ideological zealots. How they said women’s rights had to be achieved now, today; they would not wait until after the war ended to have their rights recognized. Most remarkable, Cassie said, was that they had the full respect of the men they served with in the YPG: the People’s Protection Units, which were the all-male YPJ counterpart.

“Honestly, I’m kind of jealous of them,” Cassie said. “The men have no issue with them at all. It’s almost bizarre.

“Seriously, Gayle, these women have some incredible stories. You’ve gotta come.”

I thought about our conversation for days. It just didn’t make sense that the Middle East would be home to AK-47-wielding women driven to make women’s equality a reality—and that the Americans would be the ones backing them.

Syria’s civil war had begun as a peaceful protest by children at a school in 2011 and morphed into a humanitarian catastrophe that world leaders proved utterly impotent to resolve and to which regional and global powers sent proxies to fight. The Russians, the Qataris, the Iranians, the Turks, the Saudis, and the Americans—all played their roles in the history of this war. I had written about America’s tortured efforts to settle on a Syria policy back in 2013 and 2014 and about its ultimate decision to enter the ISIS fight without taking on the Syrian regime. I had traveled to Turkey on my own to interview Syrian refugees in 2015 and share their stories. The Syrian civil war by 2016 had turned from a democratic uprising to a locally led rebellion to a full-throttle proxy war dividing those who supported the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad (Russia and Iran, most notably) and those who did not (Turkey, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, to name a few). The Islamic State had taken advantage of the power vacuum and the broader civil war to make its name and take control of territory. But it was only one group in one part of the country: rebels of different stripes with differing ideologies controlled different sections of Syria. The Assad regime held the majority of the country, including the capital, Damascus, and by 2016 the second city, Aleppo, which by then the Russians had bombed into submission.

I knew far less about this all-women’s force Cassie said I had to see. I had spotted some short pieces online and caught a CNN segment on TV, plus I saw a few photos on Twitter, which others immediately labeled “fakes” and “propaganda.” It was hard to separate the real from the fake without seeing it firsthand.

The story raised for me a whole series of questions: How had ISIS inadvertently forced the world to pay attention to an obscure militia launching a long shot of a Kurdish and women’s rights revolution in the Middle East? Does it take violence to stop violence against women? Is it possible that a far-reaching experiment in women’s emancipation could take root on the ashes of ISIS, a group that placed women’s subjugation and enslavement right at the center of its worldview? Would real equality be possible only when women took up arms?

Geography made this particular war story even more personal. Part of my father’s family came from the Kurdish region of Iraq. He was born in Baghdad and spent his early childhood in Iraq. He became a refugee while still a child because of his religion. In fact, while traveling in northern Iraq and Syria, I carried with me a passport photo of my seven-or eight-year-old father sitting with his brothers and sisters. Alongside the picture is a stamp from the Iraqi government saying that the family had ten days to exit their own country and would never be permitted to return.

The region didn’t leave my father, even when he left it for the United States. As a girl growing up in Greenbelt, Maryland, I spent weekend afternoons with my father playing soccer and backgammon, our fingernails turning red from snacking on pistachios whenever he paused his chain-smoking of Marlboro Reds. He always found the notion of women’s equality confounding. When I was ten, my father turned to me during a heated discussion I’d started about why women in his family cooked for men and waited to eat dinner until after they served their husbands and sons. He asked me one question that expressed everything:

“Do you really think men and women are equal?”

His bafflement was entirely genuine. To him, and the society in which he and his siblings had been raised, the idea could not have sounded more absurd. So I could imagine what these young women Cassie told me about faced when it came to persuading their parents to let them pick up a weapon and head into war. What I still couldn’t imagine was how they had traveled from that mindset to this moment.

A few days later I picked up my phone and wrote to Cassie on WhatsApp. One year later, in the summer of 2017, I landed in northeastern Syria.

A YOUNG WOMAN wearing olive-green fatigues and a hat pulled down low to shield her from the August Raqqa sun stepped into the concrete courtyard where we had spent the past several hours waiting. To combat boredom while the afternoon stretched on, my colleagues and I there with the PBS NewsHour had climbed onto the rooftop of the abandoned house serving as a collection point for journalists hoping to witness firsthand the fight against ISIS. We had listened to the sound of gunfire and mortars targeting the Islamic State’s positions and taken turns guessing how close the front line came to where we stood. Sometimes our minders asked us to come down; they worried that our presence on the roof distracted those charged with protecting us and didn’t want to make more work for them. Otherwise, we sat around on plastic chairs in this makeshift press center in the 118-degree heat, pleading with the Syrian forces to take us where no one with even a hint of good sense would go: the front line of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces’, or SDF’s, battle to retake the capital of the Islamic State.

The hat-wearing young soldier walked toward the stoop where we sat and began speaking with one of the young men in uniform, who pointed in our direction. Sensing that our fate was the topic of discussion, our Syrian colleague, Kamiran, stepped over to join the conversation and began explaining in Kurmanci, a Kurdish dialect, that we had only today, that we really needed to get to the front line, and that we wanted the local commander running the battle to take us.

A few minutes later, the commander for whom we had waited all day at last arrived. The moment she strode through the metal gate of the house turned press pen, we all knew who she was. The rush of our male hosts to straighten the wrinkles out of their camouflage uniforms, to stand up and outstretch their right arms to shake her hand, cemented my impression.

Klara wore a dark green, brown, and black camouflage uniform and light grey hiking boots with even lighter grey laces. Her untucked shirt draped past her waist and reached just about to the pockets of her pants, but there was nothing informal or sloppy about her. A forest-green scarf with pink, red, and yellow flowers painted on its center and fringed tassels hanging from the edges covered her hair under the throbbing sun. She looked tan from all the days out fighting in the city’s streets. I kept noticing the dimple-like cheek lines that appeared as she spoke. They seemed out of place somehow on a face that had weathered so much war.

She arrived late, she explained, because she had just visited the survivors of an ISIS car-bomb attack against a family trying to flee the city that morning. Our team had heard the “boom” earlier, but we hadn’t known its source. Most who could flee Raqqa already had by this point, but some had stayed out of the fear of the snipers and land mines they would face while attempting to escape, not to mention the U.S.-backed coalition airstrikes bombarding the city to force ISIS out of it. Some civilians didn’t want to leave their homes or couldn’t afford to give every last cent they had to smugglers, who earned their fortunes ferrying families from ISIS-held areas to liberated territory. Thousands already sat in the August heat waiting for the battle to end in a camp for the displaced in the town of Ain Issa.

Klara had gone to see the children who had survived the ISIS car bomb at a makeshift field hospital. Some of the kids had come out of the bombing unscathed. At least one of the parents had not been as lucky. After checking on the wounded, Klara had come to see us. Kamiran pleaded our case to her with a mix of charm and confidence, just as he had to her press office colleagues. I thought back on my earlier conversation with the SDF equivalent of a press representative, an Englishman.

“We aren’t taking anyone to the front line today,” he had said.

“But what if Klara is willing to take us?” I asked.

“Well, then you can go; Klara is a commander,” he answered in a tone that made it sound as though I should know this already. Klara led, he served under her, and if she said we could go, we could go.

Now Klara listened to Kamiran argue our case and agreed to take us to the front line. We would see what it looked like to fight ISIS, block by block.

Half of our team climbed into Klara’s black HiLux pickup truck, the word toyota spelled out on its back in big white block letters. (The Taliban also loved this make of truck, as I learned in Afghanistan while writing Dressmaker.) As it turned out, the first soldier we had seen, wearing the same uniform as Klara and the same black digital watch on her right wrist, plus the hat shoved down over her eyebrows, was Klara’s driver. With her at the wheel, and Klara in the passenger seat, they set off. The only “armor” I could see protecting the pickup truck was a black scarf stretched out to cover the HiLux’s back window.

If this is what it means to be backed by the Americans, I thought as I climbed into our team minivan right behind them, I’d ask for better equipment.

Driven by our British security leader, Gary, we traversed a gutted moonscape free of people and blanketed by silence. I kept looking through the window at the carcasses of the houses we passed. Who lived in these homes, and when would they return? What did they see and survive under ISIS? And what would come next for them once Klara and her fellow fighters finished the battle?

We came to a small bridge and our car slowed to a near stop.

If you’re a sniper, it must look like a bull’s-eye is painted on the roof of our minivan, I thought. If ISIS guys want to hit us, now would be the time.

I thought of Klara and the young women who served under her. They made this drive to the front line every single day; this was their commute to work. I wondered if over time the bridge lost its power to terrify. At a certain point in war, everything can become normal.

Ten minutes later—which felt like sixty—we arrived at our destination. This was as close to the front as the SDF would take us. Before us I spotted a burnt-out truck. Just that day it had been used as a bomb. Grey-black streaks of smoke still poured from its charred innards. This truck-borne explosive clearly hadn’t gone off very long ago.

Klara strode around the truck, waving her right arm here and her left arm there, pointing out the location of the attack with an unfazed air, as if she were a tour guide at a museum. She spoke of the ISIS men targeting her teammates as if she knew them. I understood why: their interaction, their proximity and mutual understanding of one another’s tactics, fighting force versus fighting force, had begun three years earlier. Our team wore body armor on our heads and torsos while Klara walked around with no armor at all, her head covered only by her green scarf.

Klara agreed to let us visit some of her troops on the way back to the press pen. At the entrance to the soldiers’ base, a house gated by black wrought iron, we stopped our convoy. Sweat dripped from my helmet onto the once white oxford I wore beneath the body armor.

As I got out of the truck and prepared to meet Klara’s forces, I realized my mistake. None of the troops we had come to see were women. And they were not Kurdish. They were young Arab men who served under Klara and the other SDF commanders.

Klara stepped out of the car and shook the men’s hands, one by one, chatting with them as she went down the row and admonishing them not to smoke cigarettes in front of the camera. She asked them about the day’s fight, talked to them about what they had seen. Some of the young men sported bandanas around their foreheads and ears to block their sweat and protect them from the heat. All of them looked exhausted. “Keep up the fight,” Klara said, offering encouragement and a flash of a dimpled smile as she left.

Fifteen minutes later, we landed at the temporary base where the young women who served under Klara stayed. The women, who ranged in age from eighteen or nineteen to forty, milled around, still in their camouflage after the day’s fight, but now lounging in stocking feet rather than standing at attention in hiking boots. They sat together in their shared living room, quietly puffing on cigarettes (the camera had been put away for the moment) and drinking cups of tea: an army of women with dark hair, black digital watches, side braids, and red-and-pink smiley-face socks. In a corner of the darkened room near the doorway, their weapons stood at the ready.

When we spoke, they made clear that their ambition went well beyond this sliver of Syria: they wanted to serve as a model for the region’s future, with women’s liberation a crucial element of their quest for a locally led, communal, and democratic society where people from different backgrounds lived together. This story was not only a military campaign, I realized, but also a political one: without the military victories, the political experiment could not take hold. For the young women fighting, what mattered most was long-term political and social change. That was why they’d signed up for this war and why they were willing to die for it. They believed beating ISIS counted as simply the first step toward defeating a mentality that said women existed only as property and as objects with which men could do whatever they wanted. Raqqa was not their destination, but only one stop in their campaign to change women’s lives and society along with it.

I could not help thinking about the parallels between these women and their enemies—not, of course, in substance, but in their commitment and their ambition. ISIS shared the grandeur and the border-crossing scope of the YPJ’s vision—in the exact opposite way. The Islamic State’s forces believed that their work would return society to the glories of the Islamic world of the seventh century. They invoked the idea of a “caliphate” ruled by a caliph, or representative of God, with centralized power and influence. The men belonging to this radical Islamist group, which trafficked in public displays of its interpretation of Sharia law, including whippings and maimings, believed that their efforts would write a new chapter not only for Syria and Iraq, but also for the entire Middle East and well beyond. ISIS placed the subjugation, enslavement, and sale of women right at the center of its ideology.

Every day, these two dueling visions of the future—and women’s roles in it—clashed in Raqqa, as they had across northeastern Syria for more than three years. The men who enslaved women faced off against the women who promised women’s emancipation and equality. Whose revolution would carry the day?

ON THE DRIVE out of Raqqa that August night in 2017, our team silent in our minivan from a mixture of heat and fatigue and released relief, I worked to stretch my imagination around what we had seen. Never had I encountered women more confident leading people, more comfortable with power and less apologetic about running things.

Whatever ambivalence I felt at the outset, this story mattered. Its impact would be felt well beyond one conflict, even a war with as much consequence as the Syrian civil war. The story had found me. I knew by then that when that happens, when a story grabs you, digs into your imagination, and presents you with questions you simply cannot answer, you either embrace the inevitable and get to work reporting or store it away in your mind and know it will find you and haunt you and gnaw at you regardless. I chose to get to work.

CHAPTER ONE

Azeema paced her breath—making it move through her quietly, nearly silently—and coached herself to do something that did not come naturally to her.

Be patient.

“Stay in your position. Hunt the enemy. You must be calm to succeed,” she said to herself. “Especially when your goal is right before you.”

If you asked any of her eleven sisters and brothers to describe her when she was young, none of them would have included the word patient in their answer. “Intense,” they would have said. “Take charge, a leader,” they would have said. Someone who acts immediately. “Determined.”

And yet here she sat, now hovering around the age of thirty, hunched over on all fours in the sniper’s perch in full stillness, her knees tucked beneath her, her body forming a near-perfect letter S as she rounded her neck to peer into the narrow square of day-light through which she would shoot her weapon. Her life and—more important, in her view—the lives of her teammates hinged on her ability to bide her time, to know just the right moment to shoot—not a fraction of a second sooner. Snipers like her played a central role in the situation in which they now found themselves: under siege in Kobani, a Kurdish town of around four hundred thousand pressed right up against the Syrian-Turkish border. Azeema and her comrades in arms had one job: defend Kobani.

“The secret is to keep calm,” she had been telling the newer snipers working alongside her and looking up to her. “No movement, no excitement. Any excitement at all, and you won’t hit your target.”

Azeema slowly leaned onto her right elbow, tilting her head ever so slightly as she looked down the barrel of her rifle. Her thick brown-black hair tried to escape the flowered blue, white, and purple scarf that covered it, but Azeema pulled the scarf down farther to fix it firmly in place. She moved her other elbow, propped up on a tan-colored sandbag, just a fraction of an inch to the left, and stayed as close to the ground as she could while she shifted her weight. Every movement mattered.

FOR AZEEMA, as for many other members of the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units, the path to the Kobani battlefield in 2014 had started during street protests in her hometown of Qamishli ten years earlier.

The Kurds made up Syria’s largest ethnic minority at roughly 10 percent of a country of around twenty-one million. The Kurds were a people split across four countries, the largest ethnic group with no state of its own. This hadn’t been the plan: The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres had promised the creation of a Kurdish state, but Turkey’s first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, rejected the treaty immediately upon taking office in 1923. The Treaty of Sèvres soon gave way to the Treaty of Lausanne, negotiated with Atatürk’s new government, which did not reference a Kurdish homeland at all. Lacking their own state, thirty million Kurds found themselves spread across what became, in the post-Ottoman era, modern-day Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. Turkey was home to the largest Kurdish population.

None of these four countries embraced Kurdish identity or the Kurds’ push for their own land. With the rise of Arab nationalist governments in Syria, the rights Kurds did enjoy began to narrow: Kurdish-language media outlets shuttered and teaching in Kurdish became illegal. By the end of the 1950s, Kurds could not apply for positions in either the police or the military.

The Syrian Kurds in many ways lived as outsiders within their nation, a regime officially known as the Syrian Arab Republic. The national government denied citizenship to tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds who missed the surprise one-day census in 1962 in the Kurdish-dominated province of Hassakeh. As a result, Kurds were unable to attain marriage and birth certificates, university slots, and passports; officially, they were stateless. The repression grew in 1963 when a coup brought the Baath Party to rule in Damascus. A decade later, the Syrian regime’s “Arab cordon” policy took Kurdish lands along the borders with Iraq and Turkey. As part of the policy, the government brought Arab families to live on these lands owned by Kurds and now confiscated by Damascus. Syrian regime teachers taught in Arabic in Kurdish-area schools—no Kurdish permitted. Kurds had no legal right to speak Kurdish and publishers no legal right to print Kurdish text. Kurds had only a minimal right to own property, no right to celebrate traditional Kurdish holidays, which remained illegal by law, and no ability to name their children in their own language or to play their own music. Anyone—Kurd or Arab—who opposed the regime faced jail or worse, and the Syrian government’s security apparatus monitored the area closely. Stepping out of line or moving against these rules meant defying a watchful regime that regularly jailed, tortured, and disappeared its enemies.

For decades, young Kurds had gone along with their elders as they sought to live their lives within the regime’s boundaries. The regime officially outlawed political parties other than its own, but Kurds still organized loosely in an alphabet soup of political organs. Yet by 2004, the winds were shifting, in no small part because Kurds across the border in Iraq had won more rights as a result of the U.S. ousting Saddam Hussein. A no-fly zone in place for decades had offered a de facto safe neighborhood for Iraqi Kurds. The 2003 ousting of the Iraqi leader who had murdered and gassed his Kurdish population had opened the way for greater recognition of Kurds’ rights in the Iraqi constitution—and had been greeted enthusiastically by young Syrian Kurds. News that U.S. president George W. Bush might soon turn to sanctioning the Syrian regime was not lost on this group.

Against this backdrop came the fateful March 2004 championship soccer match, which took place on a Friday in the largely Kurdish town of Qamishli but would have consequences across Kurdish areas. Facing off were rival soccer clubs from Qamishli and the majority-Arab town of Deir Ezzor. The usual trash-talking between fan groups soon turned ugly and political. Some reports said Kurdish fans kicked off the confrontation when they waved Kurdish flags and held signs praising George W. Bush. Others said fans from Deir Ezzor started it by holding signs with images of Saddam Hussein and by chanting insults about Iraqi Kurdish leaders. Before long, a brawl broke out. In response, the local authorities of the Syrian regime opened fire on the Kurdish side, killing more than two dozen unarmed fans and injuring around a hundred. Riots and attacks on government buildings and offices by young Kurds—including the defacing of murals honoring the now deceased Hafez al-Assad—followed. By Saturday night, Syrian state television had announced that the government would investigate the riots, which the regime blamed on some rogue elements reliant on “exported ideas.” The unrest spread to other towns in the area and became the biggest civil uprising Syria had seen in decades. Government offices were destroyed, thousands of Kurds were thrown in jail by the Assad regime, and hundreds were left wounded.

By the end of March, after nearly two weeks of upheaval, the regime had imposed order once more. Bashar al-Assad, who had taken over ruling Syria four years earlier, following his father’s death, sent tanks and armed police units into Kurdish areas, and quiet returned.

The 2004 protests marked a significant shift: Assad was growing more isolated as change came to Iraq. Young Syrian Kurds had shown that they would defy their elders and go out into the streets, despite the dangers and the risk of jail. The uprising laid bare a generational divide and exposed the will of young Syrian Kurds like Azeema, who felt impatient both with the rulers in Damascus and with their own Kurdish political leaders, who favored continued dialogue and quiet back channels over direct confrontation with Assad. Indeed, Kurdish leaders vied for the role of key interlocutor in any future talks about Kurdish rights with the Syrian regime. Some had condemned the defacement of government installations during the protests and urged an end to the unrest.

To Azeema and other young Kurds determined to shape a political future different from that of their parents, the events of March 12, 2004, showed the need for organization. The Kurds who came out to protest had no weapons and no strategy to protect themselves against the armed security forces of the Syrian regime, men willing to deploy any violence required on civilians. As Amnesty International noted, the aftermath of the incident in Qamishli brought “widespread reports of torture and ill-treatment of detainees, including children. At least five Kurds have reportedly died as a result of torture and ill-treatment in custody.” As Azeema and her friends saw it, the disarray of the Syrian Kurds during those weeks cost dearly in lives. They vowed they would be armed and far better organized the next time an opening arose.

In the wake of the 2004 protests, a Syrian Kurdish political opposition group, the recently created Democratic Union Party, went to work recruiting and organizing members. This political party traced its origins directly to a Turkish Kurdish party, the PKK, or Kurdistan Workers’ Party. Illegal like all opposition parties in Syria, the Democratic Union Party worked in secret to spread its ideas and gather followers, drawing on nearly two decades of PKK presence inside Syria.

The PKK had taken root in Syria in the late 1970s when its founder, a charismatic college dropout from southeastern Turkey named Abdullah Ocalan, brought his Marxist-Leninist movement for an independent Kurdish homeland from Turkey to Syria. Turkey had long denied Kurds nearly all their rights and even took issue with the idea that an ethnic Kurdish identity existed, instead calling the Kurds “mountain Turks.” The rebellion for Kurdish rights was bolstered following the imposition of martial law after the 1980 military coup and the enactment of the 1982 constitution, which named citizens members of the “Turkish nation” without regard for minority rights.

Ocalan came from a poor family of farmers with seven children, including a beloved sister who was married off for some money and several sacks of wheat. He studied political science at Ankara University and began to embrace Marxism while advocating for the Kurdish cause. He ended up dropping out of university after being jailed for distributing brochures and founded the PKK. Inspired by Marxist-Leninist thought, the group called for the establishment of an independent Kurdistan, with its most urgent priority the liberation of what it called northern Kurdistan, a part of Turkey. The PKK carried out its first paramilitary attack against Turkish government forces on August 15, 1984, killing two government soldiers in a coordinated assault in two southeastern provinces. One year later, a CIA memo noted that the insurgents had clashed with Turkish security forces more than thirty times and in the process taken the lives of fifty-six Turkish soldiers. These attacks grew in scale and reach over the next decade, and so did the range of targets, with the PKK using bases in the mountains of northern Iraq and in Syria as refuge.

At this time, the Syrian leader was Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, who ruled until his death in 2000. At Assad’s invitation, Ocalan fled from Turkey to Damascus, Syria, in 1979, one year after the PKK’s formation in a Turkish teahouse. The Assad regime, which denied Syrian Kurds their rights and shared none of Ocalan’s goals, hosted the Turkish Kurdish leader as a means of spiting the enemy Syrians and Kurds shared: Turkey. Syria clashed with Turkey on a number of issues, including access to water from the Euphrates River. The two also landed on opposite sides of the Cold War, with Turkey joining NATO in 1952 and the Soviet Union backing Assad’s regime. For Assad, hosting Ocalan and the PKK would keep his rivals in the Turkish capital of Ankara insecure and off-kilter. In exchange, Ocalan kept his focus on Turkey, not Syria. For two decades, Ocalan built and operated a PKK organization out of Syria and ran training camps in Lebanon from there. Quietly, his adherents taught families like Azeema’s about Kurdish rights, economic justice, and—right at the center of the work—women’s equality, even while the PKK escalated attacks in Turkey, which saw Ocalan and his organization as its chief security threat. The Syrian regime sometimes allowed Kurds to serve in the PKK’s armed wing instead of completing their state-mandated military service in the Syrian Army.

By the late 1990s, Turkey, by then growing in military and economic strength and forging diplomatic and military ties with Israel, grew impatient of demanding Ocalan’s expulsion. Ankara at last ended Syria’s support of Ocalan by repeatedly threatening military action and suspension of Syria’s water supply. Assad, no longer enjoying Soviet backing, agreed to Turkey’s decades-long demand to evict the PKK’s founder. The Syrian regime threw Ocalan out of the country in October 1998, forcing him to hunt for asylum and his PKK forces to find refuge in northern Iraq’s Qandil Mountains, thus ending two decades of Ocalan’s presence and influence in Syria. By then, Turkey also had persuaded the Americans to get involved in cracking down on Ocalan and the PKK: In 1997, the U.S. agreed to Turkey’s request to designate the PKK, which Turkey counted as responsible for close to forty thousand deaths, as a terrorist organization. Not long after Ocalan fled Syria, U.S. surveillance information helped Turkey arrest him as he sought safety in Nairobi, Kenya. Turkey sentenced its highest-profile prisoner to death in 1999, but revised the sentence to life in prison after abolishing the death penalty in 2002. Since 1999, Turkey has imprisoned Ocalan in a one-man jail on Imrali Island in the Marmara Sea.

Turkey may have considered Ocalan its most-wanted man, but for the Syrian Kurds who followed him, Ocalan lived in the public imagination somewhere between Nelson Mandela and George Washington. Central to his teachings was the position that Kurdish rights could not be divorced from women’s liberation because the enslavement of women had enabled the enslavement of men. Ocalan stated that the Neolithic order of a matriarchal society in which everyone was protected and people enjoyed communal property, sharing of resources, and a lack of social and institutional hierarchy had given way to a social order in which women’s work became relegated to the home, women’s rights had been denied, and women faced what he termed the “housewifization” of their contributions. Modern capitalism had taken people’s freedoms and exploited its workers, spreading sexism and nationalism:

The 5,000-year-old history of civilization is essentially the history of the enslavement of woman. Consequently, woman’s freedom will only be achieved by waging a struggle against the foundations of this ruling system.

IN 2011, the start of the Syrian civil war stirred fear among Kurds determined to protect their lands. What the next months would bring as the Syrian regime moved to put down the first armed threat to its rule was anyone’s guess. A mix of young people from around the majority-Kurdish regions in northeastern Syria signed up to defend their neighborhoods under the umbrella of the newly formed People’s Protection Units. Azeema was among the recruits who joined at this time. She felt as if she had to get involved to protect the Kurds from outsiders, whether they were anti-Assad rebels who wanted to take Kurdish land or regime forces rolling in to crack down even further on their area. She also strongly shared Ocalan’s view that the Kurds couldn’t be free if women weren’t. Her father followed Ocalan, and Azeema and her siblings had been raised on his teachings. The children had heard the tale from their father about his grandmother, who had been an elder in charge of her Turkish Kurdish village at a time when all the other leaders were men. Politics in Syria remained largely dominated by men, regardless of community, but women across the country were coming out into the streets to organize protests. Among the Syrian Kurds, women played a growing role. Azeema intended to be part of the movement.

When she was thirteen, Azeema sat outside in the courtyard of her house in Qamishli with one of her older sisters, trying to survive the summer’s oppressive nighttime heat by watching her favorite Syrian soap opera, which aired each night at 7:00 p.m. One of the main characters faced beatings and abuse from her husband, and no one stood up to help her. Azeema’s sister had gotten engaged not long before, and Azeema began to connect the woman on the television with her sister sitting next to her.

“You shouldn’t get married,” Azeema told her. “How can you possibly think of it?”

Her sister sat on the rug, propped up on one of their plush pillows, hunting for a breeze and trying to relax. “You’re crazy,” she said. “Marriage isn’t like that. Mine isn’t going to be, at least. Just watch the show.”

“Maybe I’m crazy,” Azeema said, sitting up, her pursed lips showing she thought no such thing. “But I am not going to get married. Haven’t you been watching? Why would you get married? Look what this thing is like.”

She gestured toward the TV and kept speaking, despite being aware that her sister was no longer listening.

“I don’t see how you can watch this show, know that this is what goes on, and still want to marry anyone,” Azeema said. “I’m never getting married. Ever. And you should break off your engagement.”

Her position on marriage had not softened over the decade and a half since.

When Azeema first took up arms in 2011, she didn’t join the People’s Protection Units expecting she would actually end up killing anyone. Indeed, the YPG didn’t yet exist; she joined the training academy of the YXK, Yekîtiya Xwendekarên Kurdistanê, or Student Union of Kurdistan. The idea was to protect Kurds against the Syrian regime—as they had failed to do in 2004—if it came barreling through with its tanks to crack down harshly on the area, and to keep out others who wanted to try to take over their land, including any Islamist extremists hostile to Kurdish rights.

At her first meeting to learn more about the self-defense units, Azeema gathered with a handful of others in secret in a local hall in Qamishli. Everyone feared the government would find out about their assembly, even though Assad’s men had their hands full dealing with opposition forces seeking to topple the regime. At the meeting, Syrian men who had been trained by the PKK in northern Iraq’s Qandil Mountains, and who had returned home once the civil war started, talked to the gathered twentysomethings about the need to organize and learn the basics of weaponry and military tactics.

As she looked at the two or three dozen people who had come together in that unremarkable room with its bare walls in her home-town of Qamishli, Azeema felt excitement and pride. This was what she had hoped to join since 2004: a movement of Kurds standing up to protect themselves. She knew that being part of a militia carried risks and that she would face imprisonment and perhaps torture if the regime caught her, but despite the danger, she felt as though her life finally was beginning to take the shape she wanted. She had stood out for years as a leader: in high school, she made her name as a volleyball star skilled enough to help lead her team to victory at a regional competition in the coastal resort town of Latakia. She loved the sport’s intensity, relentlessness, and teamwork. Her skill landed her a photo spread in a local magazine, which her younger sister proudly shared with the entire family.

Looking across the room to see who else had dared to join this clandestine gathering, Azeema raised her eyebrows and felt her serious expression give way to an unguarded smile: her childhood friend and distant relative Rojda was there, too. Azeema could be brash and loud, shouting plays to her volleyball teammates across the court in an unmissable bellowing baritone. Rojda, who loved soccer enough to defy every family admonition that it was a sport that belonged to boys, had never bellowed at anyone in her life, even while calling for the ball. Indeed, no one had ever seen her temper escalate or heard her voice rise above a firm, quiet tone. The extroverted Azeema would take on anyone she encountered and shout down anyone who got in her way. The introverted Rojda, on the other hand, preferred picking up a new book to meeting a new person, and if someone gave her a hard time, she would tell Azeema, knowing that her outspoken friend would either beat them up or scare them away with the threat of doing so.

One of Rojda’s uncles lived near Azeema, and Rojda regularly ended up at Azeema’s house after school. Together with their friend Fatima, they would make their way through Azeema’s neighborhood each day when classes ended and pick up their favorite ice cream on the way to Azeema’s house. Boys would catcall them and try to follow them home, but Azeema would turn around and shoo them away. “Get lost,” she would shout. “No one wants to talk to you.” Fatima and Rojda would hide behind Azeema while she went on the offensive. “Azeema,” Rojda joked, “no one is going to marry you. You are just like the boys!”

Azeema laughed. “Rojda, you know I am never getting married.”

“But you have to,” Fatima said. “What are you going to do, live at home forever?”