Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: 7 best short stories

- Sprache: Englisch

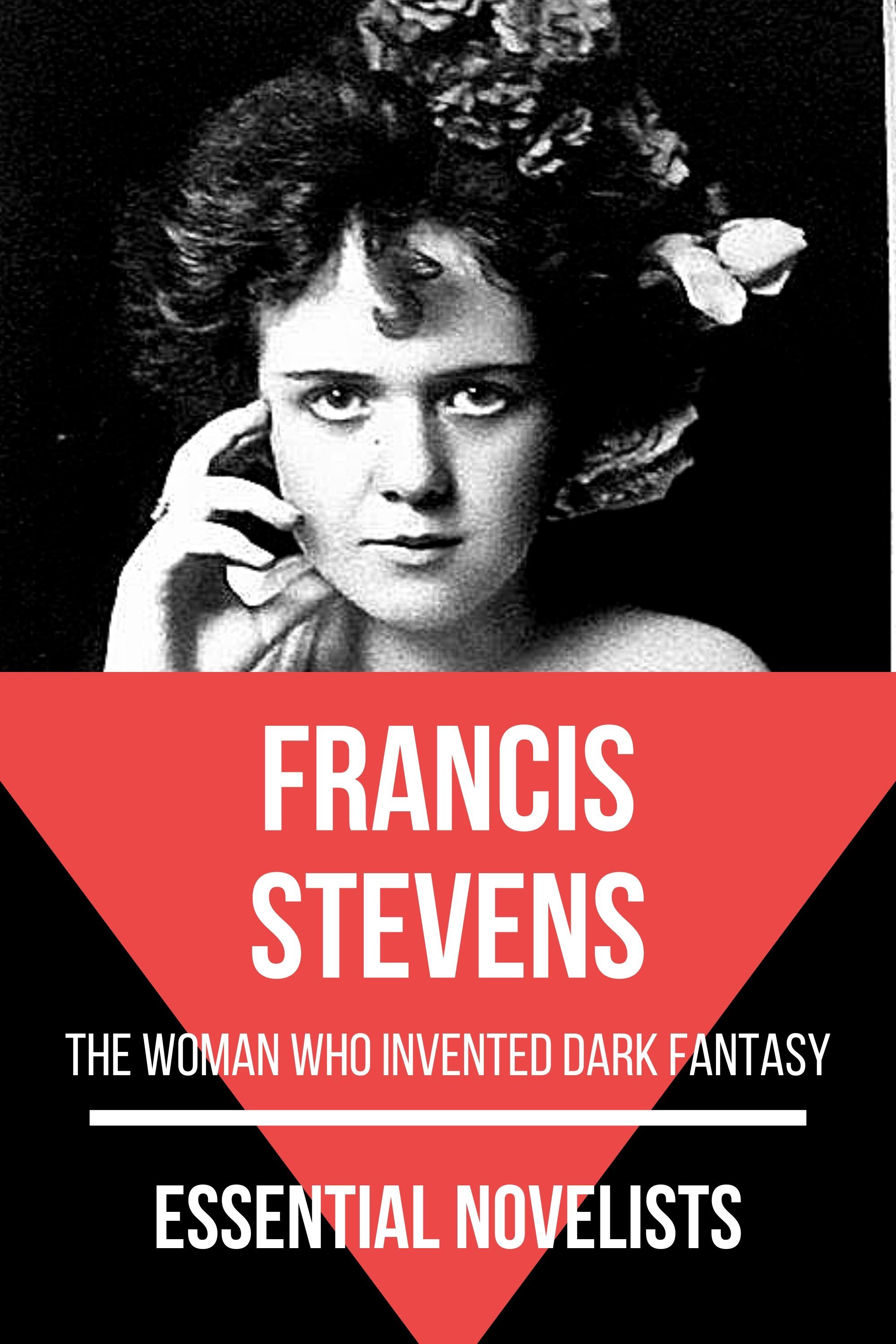

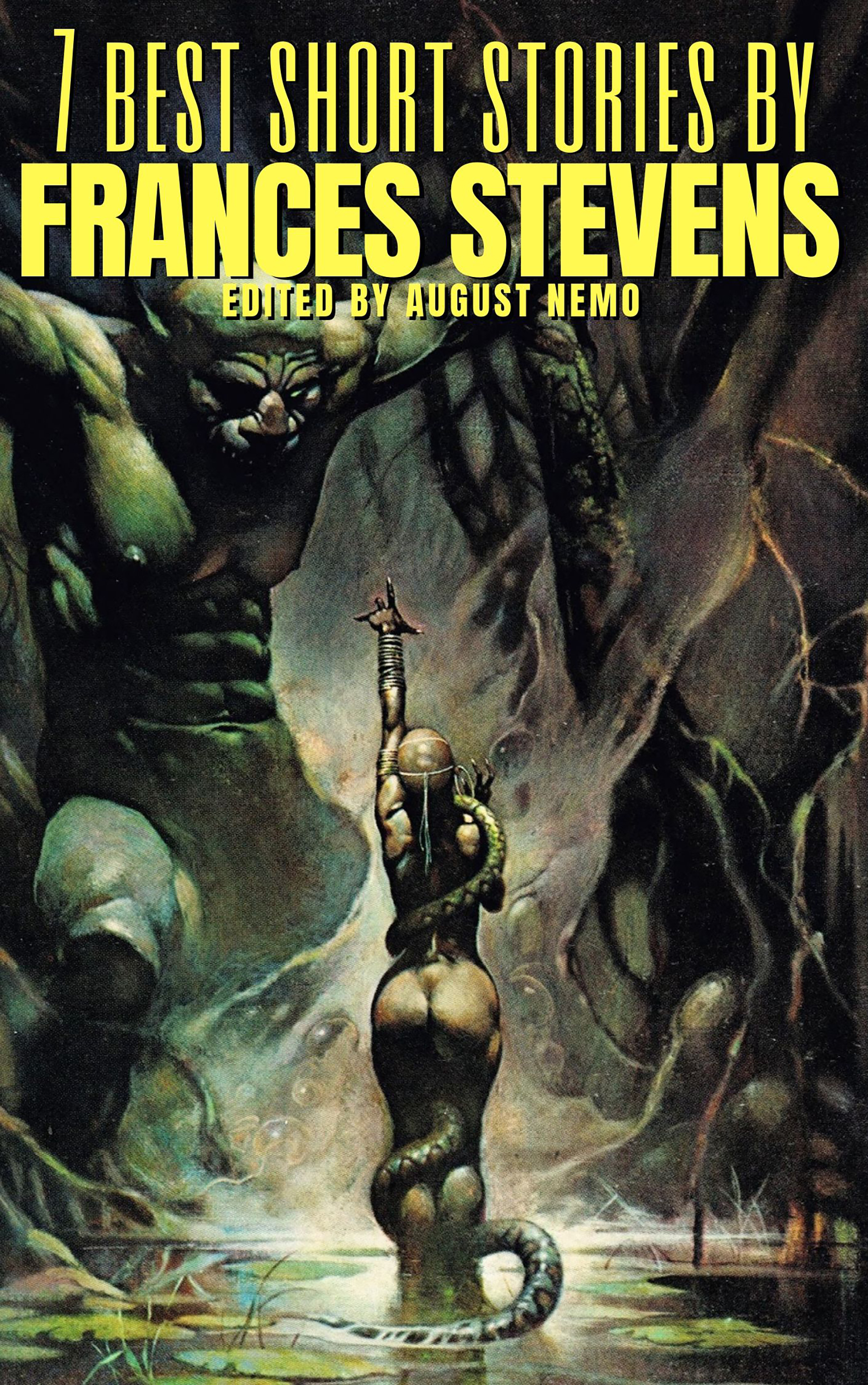

Gertrude Barrows Bennett, known by the pseudonym Francis Stevens, was a pioneering author of fantasy and science fiction. Bennett wrote a number of fantasies and has been called "the woman who invented dark fantasy". ] The critic August Nemo selected seven short stories by this remarkable author for your enjoyment: - Behind the Curtain. - Unseen Unfeared. - Elf Trap. - Serapion. - Friend Island. - Citadel of Fear. - Nightmare!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 668

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

The Author

Behind the Curtain

Unseen — Unfeared

Elf Trap

Serapion

Friend Island

Citadel of fear

Nightmare!

About the Publisher

The Author

Gertrude Mabel Barrows was born in Minneapolis in 1884, to Charles and Caroline Barrows (née Hatch). Her father, a Civil War veteran from Illinois, died in 1892. Gertrude completed school through the eighth grade, then attended night school in hopes of becoming an illustrator (a goal she never achieved). Instead, she began working as a stenographer, a job she held on and off for the rest of her life.

In 1909 Barrows married Stewart Bennett, a British journalist and explorer, and moved to Philadelphia. A year later her husband died during a tropical storm while on a treasure hunting expedition. With a new-born daughter to raise, Bennett continued working as a stenographer. When her father died toward the end of World War I, Bennett assumed care for her invalid mother.

During this time period Bennett began to write a number of short stories and novels, only stopping when her mother died in 1920. In the mid-1920s, she moved to California. Because Bennett was estranged from her daughter, for a number of years researchers believed Bennett died in 1939 (the date of her final letter to her daughter). However, new research, including her death certificate, shows that she died in 1948.

Gertrude Mabel Barrows (as she then was) wrote her first short story at age 17, a science fiction story titled "The Curious Experience of Thomas Dunbar". She mailed the story to Argosy, then one of the top pulp magazines. The story was accepted and published in the March 1904 issue, under the byline "G.M. Barrows". Although the initials disguised her gender, this appears to be the first instance of an American female author publishing science fiction, and using her real name.

Once Bennett began to take care of her mother, she decided to return to fiction writing as a means of supporting her family. The first story she completed after her return to writing was the novella "The Nightmare," which appeared in All-Story Weekly in 1917. The story is set on an island separated from the rest of the world, on which evolution has taken a different course. "The Nightmare" resembles Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Land That Time Forgot, itself published a year later. While Bennett had submitted "The Nightmare" under her own name, she had asked to use a pseudonym if it was published. The magazine's editor chose not to use the pseudonym Bennett suggested (Jean Vail) and instead credited the story to Francis Stevens. When readers responded positively to the story, Bennett chose to continue writing under the name.

Over the next few years, Bennett wrote a number of short stories and novellas. Her short story "Friend Island" (All-Story Weekly, 1918), for example, is set in a 22nd-century ruled by women. Another story is the novella "Serapion" (Argosy, 1920), about a man possessed by a supernatural creature. This story has been released in an electronic book entitled Possessed: A Tale of the Demon Serapion, with three other stories by her. Many of her short stories have been collected in The Nightmare and Other Tales of Dark Fantasy (University of Nebraska Press, 2004).

In 1918 she published her first, and perhaps best, novel The Citadel of Fear (Argosy, 1918). This lost world story focuses on a forgotten Aztec city, which is "rediscovered" during World War I. It was in the introduction to a 1952 reprint edition of the novel which revealed for the first time that "Francis Stevens" was Bennett's pen-name.

A year later she published her only science fiction novel, The Heads of Cerberus (The Thrill Book, 1919). One of the first dystopian novels, the book features a "grey dust from a silver phial" which transports anyone who inhales it to a totalitarian Philadelphia of 2118 AD.

One of Bennett's most famous novels was Claimed! (Argosy, 1920; reprinted 1966, 2004, 2018), in which a supernatural artifact summons an ancient and powerful god to early 20th century New Jersey. Augustus T. Swift called the novel, "One of the strangest and most compelling science fantasy novels you will ever read".

Behind the Curtain

IT WAS after nine o’clock when the bell rang, and descending to the dimly lighted hall I opened the front door, at first on the chain to be sure of my visitor. Seeing, as I had hoped, the face of our friend, Ralph Quentin, I took off the chain and he entered with a blast of sharp November air for company. I had to throw my weight upon the door to close it against the wind.

As he removed his hat and cloak he laughed good-humoredly.

“You’re very cautious, Santallos. I thought you were about to demand a password before admitting me.”

“It is well to be cautious,” I retorted. “This house stands somewhat alone, and thieves are everywhere.”

“It would require a thief of considerable muscle to make off with some of your treasures. That stone tomb-thing, for instance; what do you call it?”

“The Beni Hassan sarcophagus. Yes. But what of the gilded inner case, and what of the woman it contains? A thief of judgment and intelligence might covet that treasure and strive to deprive me of it. Don’t you agree?”

He only laughed again, and counterfeited a shudder.

“The woman! Don’t remind me that such a brown, shriveled, mummy-horror was ever a woman!”

“But she was. Doubtless in her day my poor Princess of Naarn was soft, appealing; a creature of red, moist lips and eyes like stars in the black Egyptian sky. ‘The Songstress of the House’ she was called, ere she became Ta–Nezem the Osirian. But I keep you standing here in the cold hall. Come upstairs with me. Did I tell you that Beatrice is not here tonight?”

“No?” His intonation expressed surprise and frank disappointment. “Then I can’t say good-by to her? Didn’t you receive my note? I’m to take Sanderson’s place as manager of the sales department in Chicago, and I’m off tomorrow morning.”

“Congratulations. Yes, we had your note, but Beatrice was given an opportunity to join some friends on a Southern trip. The notice was short, but of late she has not been so well and I urged her to go. This November air is cruelly damp and bitter.”

“What was it — a yachting cruise?”

“A long cruise. She left this afternoon. I have been sitting in her boudoir, Quentin, thinking of her, and I’ll tell you about it there — if you don’t mind?”

“Wherever you like,” he conceded, though in a tone of some surprise. I suppose he had not credited me with so much sentiment, or thought it odd that I should wish to share it with another, even so good a friend as he. “You must find it fearfully lonesome here without Bee,” he continued.

“A trifle.” We were ascending the dark stairs now. “After tonight, however, things will be quite different. Do you know that I have sold the house?”

“No! Why, you are full of astonishments, old chap. Found a better place with more space for your tear-jars and tombstones?”

He meant, I assumed, a witty reference to my collection of Coptic and Egyptian treasures, well and dearly bought, but so much trash to a man of Quentin’s youth and temperament.

I opened the door of my wife’s boudoir, and it was pleasant to pass into such rosy light and warmth out of the stern, dark cold of the hall. Yet it was an old house, full of unexpected drafts. Even here there was a draft so strong that a heavy velour curtain at the far side of the room continually rippled and billowed out, like a loose rose-colored sail. Never far enough, though, to show what was behind it.

My friend settled himself on the frail little chair that stood before my wife’s dressing-table. It was the kind of chair that women love and most men loathe, but Quentin, for all his weight and stature, had a touch of the feminine about him, or perhaps of the feline. Like a cat, he moved delicately. He was blond and tall, with fine, regular features, a ready laugh, and the clean charm of youth about him — also its occasional blundering candor.

As I looked at him sitting there, graceful, at ease, I wished that his mind might have shared the litheness of his body. He could have understood me so much better.

“I have indeed found a place for my collections,” I observed, seating myself near by. “In fact, with a single exception — the Ta–Nezem sarcophagus — the entire lot is going to the dealers.” Seeing his expression of astonished disbelief I continued: “The truth is, my dear Quentin, that J have been guilty of gross injustice to our Beatrice. I have been too good a collector and too neglectful a husband. My ‘tear-jars and tombstones,’ in fact, have enjoyed an attention that might better have been elsewhere bestowed. Yes, Beatrice has left me alone, but the instant that some few last affairs are settled I intend rejoining her. And you yourself are leaving. At least, none of us three will be left to miss the others’ friendship.”

“You are quite surprising tonight, Santallos. But, by Jove, I’m not sorry to hear any of it! It’s not my place to criticize, and Bee’s not the sort to complain. But living here in this lonely old barn of a house, doing all her own work, practically deserted by her friends, must have been — ”

“Hard, very hard,” I interrupted him softly, “for one so young and lovely as our Beatrice. But if I have been blind at least the awakening has come. You should have seen her face when she heard the news. It was wonderful. We were standing, just she and I, in the midst of my tear-jars and tombstones — my ‘chamber of horrors’ she named it. You are so apt at amusing phrases, both of you. We stood beside the great stone sarcophagus from the Necropolis of Beni Hassan. Across the trestles beneath it lay the gilded inner case wherein Ta–Nezem the Osirian had slept out so many centuries. You know its appearance. A thing of beautiful, gleaming lines, like the quaint, smiling image of a golden woman.

“Then I lifted the lid and showed Beatrice that the one-time songstress, the handmaiden of Amen, slept there no more, and the case was empty. You know, too, that Beatrice never liked my princess. For a jest she used to declare that she was jealous. Jealous of a woman dead and ugly so many thousand years! Or — but that was only in anger — that I had bought Ta–Nezem with what would have given her, Beatrice, all the pleasure she lacked in life. Oh, she was not too patient to reproach me, Quentin, but only in anger and hot blood.

“So I showed her the empty case, and I said, ‘Beloved wife, never again need you be jealous of Ta–Nezem. All that is in this room save her and her belongings I have sold, but her I could not bear to sell. That which I love, no man else shall share or own. So I have destroyed her. I have rent her body to brown, aromatic shreds. I have burned her; it is as if she had never been. And now, dearest of the dear, you shall take for your own all the care, all the keeping that Heretofore I have lavished upon the Princess of Naam.’

“Beatrice turned from the empty case as if she could scarcely believe her hearing, but when she saw by the look in my eyes that I meant exactly what I said, neither more nor less, you should have seen her face, my dear Quentin — you should have seen her face!”

“I can imagine.” He laughed, rather shortly. For some reason my guest seemed increasingly ill at ease, and glanced continually about the little rose-and-white room that was the one luxurious, thoroughly feminine corner — that and the cold, dark room behind the curtain — in what he had justly called my “barn of a house.”

“Santallos,” he continued abruptly, and I thought rather rudely, “you should have a portrait done as you look tonight. You might have posed for one of those stern old hidalgos of — which painter was it who did so many Spanish dons and donesses?”

“You perhaps mean Velasquez,” I answered with mild courtesy, though secretly and as always his crude personalities displeased me. “My father, you may recall, was of Cordova in southern Spain. But — must you go so soon? First drink one glass with me to our missing Beatrice. See how I was warming my blood against the wind that blows in, even here. The wine is Amontillado, some that was sent me by a friend of my father’s from the very vineyards where the grapes were grown and pressed. And for many years it has ripened since it came here. Before she went, Beatrice drank of it from one of these same glasses. True wine of Montilla! See how it lives — like fire in amber, with a glimmer of blood behind it.”

I held high the decanter and the light gleamed through it upon his face.

“Amontillado! Isn’t that a kind of sherry? I’m no connoisseur of wines, as you know. But–Amontillado.”

For a moment he studied the wine I had given him, liquid flame in the crystal glass. Then his face cleared.

“I remember the association now. ‘The Cask of Amontillado.’ Ever read the story?”

“I seem to recall it dimly.”

“Horrible, fascinating sort of a yarn. A fellow takes his trustful friend down into the cellars to sample some wine, traps him and walls him up in a niche. Buries him alive, you understand. Read it when I was a youngster, and it made a deep impression, partly, I think, because I couldn’t for the life of me comprehend a nature — even an Italian nature — desiring so horrible a form of vengeance. You’re half Latin yourself, Santallos. Can you elucidate?”

“I doubt if you would ever understand,” I responded slowly, wondering how even Quentin could be so crude, so tactless. “Such a revenge might have its merits, since the offender would be a long time dying. But merely to kill seems to me so pitifully inadequate. Now I, if I were driven to revenge, should never be contented by killing. I should wish to follow.”

“What — beyond the grave?”

I laughed. “Why not? Wouldn’t that be the very apotheosis of hatred? I’m trying to interpret the Latin nature, as you asked me to do.”

“Confound you, for an instant I thought you were serious. The way you said it made me actually shiver!”

“Yes,” I observed, “or perhaps it was the draft. See, Quentin, how that curtain billows out.”

His eyes followed my glance. Continually the heavy, rose-colored curtain that wag hung before the door of my wife’s bedroom bulged outward, shook and quivered like a bellying sail, as draperies will with a wind behind them.

His eyes strayed from the curtain, met mine and fell again to the wine in his glass. Suddenly he drained it, not as would a man who was a judge of wines, but hastily, indifferently, without thought for its flavor or bouquet. I raised my glass in the toast he had forgotten.

“To our Beatrice,” I said, and drained mine also, though with more appreciation.

“To Beatrice — of course.” He looked at the bottom of his empty glass, then before I could offer to refill it, rose from his chair.

“I must go, old man. When you write to Bee, tell her I’m sorry to have missed her.”

“Before she could receive a letter from me I shall be with her — I hope. How cold the house is tonight, and the wind breathes everywhere. See how the curtain blows, Quentin.”

“So it does.” He set his glass on the tray beside the decanter. Upon first entering the room he had been smiling, but now his straight, fine brows were drawn in a perpetual, troubled frown, his eyes looked here and there, and would never meet mine — which were steady. “There’s a wind,” he added, “that blows along this wall — curious. One can’t notice any draft there, either. But it must blow there, and of course the curtain billows out.”

“Yes,” I said. “Of course it billows out.”

“Or is there another door behind that curtain?”

His careful ignorance of what any fool might infer from mere appearance brought an involuntary smile to my lips. Nevertheless, I answered him.

“Yes, of course there is a door. An open door.”

His frown deepened. My true and simple replies appeared to cause him a certain irritation.

“As I feel now,” I added, “even to cross the room would be an effort. I am tired and weak tonight. As Beatrice once said, my strength beside yours is as a child’s to that of a grown man. Won’t you close that door for me, dear friend?”

“Why — yes, I will. I didn’t know you were ill. If that’s the case, you shouldn’t be alone in this empty house. Shall I stay with you for a while?”

As he spoke he walked across the room. His hand was on the curtain, but before it could be drawn aside my voice checked him.

“Quentin,” I said, “are even you quite strong enough to close that door?”

Looking back at me, chin on shoulder, his face appeared scarcely familiar, so drawn was it in lines of bewilderment and half-suspicion.

“What do you mean? You are very odd tonight. Is the door so heavy then? What door is it?”

I made no reply.

As if against their owner’s will his eyes fled from mine, he turned and hastily pushed aside the heavy drapery.

Behind it my wife’s bedroom lay dark and cold, with windows open to the invading winds.

And erect in the doorway, uncovered, stood an ancient gilded coffin-case. It was the golden casket of Ta–Nezem, but its occupant was more beautiful than the poor, shriveled Songstress of Naam.

Bound across her bosom were the strange, quaint jewels which had been found in the sarcophagus. Ta–Nezem’s amulets — heads of Hathor and Horus the sacred eye, the uroeus, even the heavy dull-green scarab, the amulet for purity of heart — there they rested upon the bosom of her who had been mistress of my house, now Beatrice the Osirian. Beneath them her white, stiff body was enwrapped in the same crackling dry, brown linen bands, impregnated with the gums and resins of embalmers dead these many thousand years, which had been about the body of Ta–Nezem.

Above the white translucence of her brow appeared the winged disk, emblem of Ra. The twining golden bodies of its supporting uraeii, its cobras of Egypt, were lost in the dusk of her hair, whose soft fineness yet lived and would live so much longer than the flesh of any of us three.

Yes, I had kept my word and given to Beatrice all that had been Ta-Nezem’s, even to the sarcophagus itself, for in my will it was written that she be placed in it for final burial.

Like the fool he was, Quentin stood there, staring at the unclosed, frozen eyes of my Beatrice — and his. Stood till that which had been in the wine began to make itself felt. He faced me then, but with so absurd and childish a look of surprise that, despite the courtesy due a guest, I laughed and laughed.

I, too, felt warning throes, but to me the pain was no more than a gage — a measure of his sufferings stimulus to point the phrases in which I told him all I knew and had guessed of him and Beatrice, and thus drive home the jest.

But I had never thought that a man of Quentin’s youth and strength could die so easily. Beatrice, frail though she was, had taken longer to die.

He could not even cross the room to stop my laughter, but at the first step stumbled, fell, and in a very little while lay at the foot of the gilded case.

After all, he was not so strong as I. Beatrice had seen. Her still, cold eyes saw all. How he lay there, his fine, lithe body contorted, worthless for any use till its substance should have been cast again in the melting-pot of dissolution, while I who had drunk of the same draft, suffered the same pangs, yet stood and found breath for mockery.

So I poured myself another glass of that good Cordovan wine, and I raised it to both of them and drained it, laughing.

“Quentin,” I cried, “you asked what door, though your thought was that you had passed that way before, and feared that I guessed your, knowledge. But there are doors and doors, dear, charming friend, and one that is heavier than any other. Close it if you can. Close it now in my face, who otherwise will follow even whither you have gone — the heavy, heavy door of the Osiris, Keeper of the House of Death!”

Thus I dreamed of doing and speaking. It was so vivid, the dream, that awakening in the darkness of my room I could scarcely believe that it had been other than reality. True, I lived, while in my dream I had shared the avenging poison. Yet my veins were still hot with the keen passion of triumph, and my eyes filled with the vision of Beatrice, dead — dead in Ta–Nezem’s casket.

Unreasonably frightened. I sprang from bed, flung on a dressing-gown, and hurried out. Down the hallway I sped, swiftly and silently, at the end of it unlocked heavy doors with a tremulous hand, switched on lights, lights and more lights, till the great room of my collection was ablaze with them, and as my treasures sprang into view I sighed, like a man reaching home from a perilous journey.

The dream was a lie.

There, fronting me, stood the heavy empty sarcophagus; there on the trestles before it lay the gilded case, a thing of beautiful, gleaming lines, like the smiling image of a golden woman.

I stole across the room and softly, very softly, lifted the upper half of the beautiful lid, peering within. The dream indeed was a lie.

Happy as a comforted child I went to my room again. Across the hall the door of my wife’s boudoir stood partly open.

In the room beyond a faint light was burning, and I could see the rose-colored curtain sway slightly to a draft from some open window.

Yesterday she had come to me and asked for her freedom. I had refused, knowing to whom she would turn, and hating him for his youth, and his crudeness and his secret scorn of me.

But had I done well? They were children, those two, and despite my dream I was certain that their foolish, youthful ideals had kept them from actual sin against my honor. But what if, time passing, they might change? Or, Quentin gone, my lovely Beatrice might favor another, young as he and not so scrupulous?

Every one, they say, has a streak of incipient madness. I recalled the frenzied act to which my dream jealousy had driven me. Perhaps it was a warning, the dream. What if my father’s jealous blood should some day betray me, drive me to the insane destruction of her I held most dear and sacred.

I shuddered, then smiled at the swaying curtain. Beatrice was too beautiful for safety. She should have her freedom.

Let her mate with Ralph Quentin or whom she would, Ta–Nezem must rest secure in her gilded house of death. My brown, perfect, shriveled Princess of the Nile! Destroyed — rent to brown, aromatic shreds — burned — destroyed — and her beautiful coffin-case desecrated as I had seen it in my vision’.

Again I shuddered, smiled and shook my head sadly at the swaying, rosy curtain.

“You are too lovely, Beatrice,” I said, “and my father was a Spaniard. You shall have your freedom!”

I entered my room and lay down to sleep again, at peace and content.

The dream, thank God, was a lie.

Unseen — Unfeared

I

Ihad been dining with my ever-interesting friend, Mark Jenkins, at a little Italian restaurant near South Street. It was a chance meeting. Jenkins is too busy, usually, to make dinner engagements. Over our highly seasoned food and sour, thin, red wine, he spoke of little odd incidents and adventures of his profession. Nothing very vital or important, of course. Jenkins is not the sort of detective who first detects and then pours the egotistical and revealing details of achievement in the ears of every acquaintance, however appreciative.

But when I spoke of something I had seen in the morning papers, he laughed. “Poor old ‘Doc’ Holt! Fascinating old codger, to anyone who really knows him. I’ve had his friendship for years — since I was first on the city force and saved a young assistant of his from jail on a false charge. And they had to drag him into the poisoning of this young sport, Ralph Peeler!”

“Why are you so sure he couldn’t have been implicated?” I asked.

But Jenkins only shook his head, with a quiet smile. “I have reasons for believing otherwise,” was all I could get out of him on that score, “But,” he added, “the only reason he was suspected at all is the superstitious dread of these ignorant people around him. Can’t see why he lives in such a place. I know for a fact he doesn’t have to. Doc’s got money of his own. He’s an amateur chemist and dabbler in different sorts of research work, and I suspect he’s been guilty of ‘showing off.’ Result, they all swear he has the evil eye and holds forbidden communion with invisible powers. Smoke?”

Jenkins offered me one of his invariably good cigars, which I accepted, saying thoughtfully: “A man has no right to trifle with the superstitions of ignorant people. Sooner or later, it spells trouble.”

“Did in his case. They swore up and down that he sold love charms openly and poisons secretly, and that, together with his living so near to — somebody else — got him temporarily suspected. But my tongue’s running away with me, as usual!”

“As usual,” I retorted impatiently, “you open up with all the frankness of a Chinese diplomat.”

He beamed upon me engagingly and rose from the table, with a glance at his watch. “Sorry to leave you, Blaisdell, but I have to meet Jimmy Brennan in ten minutes.”

He so clearly did not invite my further company that I remained seated for a little while after his departure; then took my own way homeward. Those streets always held for me a certain fascination, particularly at night. They are so unlike the rest of the city, so foreign in appearance, with their little shabby stores, always open until late evening, their unbelievably cheap goods, displayed as much outside the shops as in them, hung on the fronts and laid out on tables by the curb and in the street itself. Tonight, however, neither people nor stores in any sense appealed to me. The mixture of Italians, Jews and a few Negroes, mostly bareheaded, unkempt and generally unhygienic in appearance, struck me as merely revolting. They were all humans, and I, too, was human. Some way I did not like the idea.

Puzzled a trifle, for I am more inclined to sympathize with poverty than accuse it, I watched the faces that I passed. Never before had I observed how bestial, how brutal were the countenances of the dwellers in this region. I actually shuddered when an old-clothes man, a gray-bearded Hebrew, brushed me as he toiled past with his barrow.

There was a sense of evil in the air, a warning of things which it is wise for a clean man to shun and keep clear of. The impression became so strong that before I had walked two squares I began to feel physically ill. Then it occurred to me that the one glass of cheap Chianti I had drunk might have something to do with the feeling. Who knew how that stuff had been manufactured, or whether the juice of the grape entered at all into its ill-flavored composition? Yet I doubted if that were the real cause of my discomfort.

By nature I am rather a sensitive, impressionable sort of chap. In some way tonight this neighborhood, with its sordid sights and smells, had struck me wrong.

My sense of impending evil was merging into actual fear. This would never do. There is only one way to deal with an imaginative temperament like mine — conquer its vagaries. If I left South Street with this nameless dread upon me, I could never pass down it again without a recurrence of the feeling. I should simply have to stay here until I got the better of it — that was all.

I paused on a corner before a shabby but brightly lighted little drug store. Its gleaming windows and the luminous green of its conventional glass show jars made the brightest spot on the block. I realized that I was tired, but hardly wanted to go in there and rest. I knew what the company would be like at its shabby, sticky soda fountain. As I stood there, my eyes fell on a long white canvas sign across from me, and its black-and-red lettering caught my attention.

SEE THE GREAT UNSEEN!

Come in! This Means You!

FREE TO ALL!

A museum of fakes, I thought, but also reflected that if it were a show of some kind I could sit down for a while, rest, and fight off this increasing obsession of nonexistent evil. That side of the street was almost deserted, and the place itself might well be nearly empty.

II

Iwalked over, but with every step my sense of dread increased. Dread of I knew not what. Bodiless, inexplicable horror had me as in a net, whose strands, being intangible, without reason for existence, I could by no means throw off. It was not the people now. None of them were about me. There, in the open, lighted street, with no sight nor sound of terror to assail me, I was the shivering victim of such fear as I had never known was possible. Yet still I would not yield.

Setting my teeth, and fighting with myself as with some pet animal gone mad, I forced my steps to slowness and walked along the sidewalk, seeking entrance. Just here there were no shops, but several doors reached in each case by means of a few iron-railed stone steps. I chose the one in the middle beneath the sign. In that neighborhood there are museums, shops and other commercial enterprises conducted in many shabby old residences, such as were these. Behind the glazing of the door I had chosen I could see a dim, pinkish light, but on either side the windows were quite dark.

Trying the door, I found it unlocked. As I opened it a party of Italians passed on the pavement below and I looked back at them over my shoulder. They were gayly dressed, men, women and children, laughing and chattering to one another; probably on their way to some wedding or other festivity.

In passing, one of the men glanced up at me and involuntarily I shuddered back against the door. He was a young man, handsome after the swarthy manner of his race, but never in my life had I see a face so expressive of pure, malicious cruelty, naked and unashamed. Our eyes met and his seemed to light up with a vile gleaming, as if all the wickedness of his nature had come to a focus in the look of concentrated hate he gave me.

They went by, but for some distance I could see him watching me, chin on shoulder, till he and his party were swallowed up in the crowd of marketers farther down the street.

Sick and trembling from that encounter, merely of eyes though it had been, I threw aside my partly smoked cigar and entered. Within there was a small vestibule, whose ancient tesselated floor was grimy with the passing of many feet. I could feel the grit of dirt under my shoes, and it rasped on my rawly quivering nerves. The inner door stood partly open, and going on I found myself in a bare, dirty hallway, and was greeted by the sour, musty, poverty-stricken smell common to dwellings of the very ill-to-do. Beyond there was a stairway, carpeted with ragged grass matting. A gas jet, turned low inside a very dusty pink globe, was the light I had seen from without.

Listening, the house seemed entirely silent. Surely, this was no place of public amusement of any kind whatever. More likely it was a rooming house, and I had, after all, mistaken the entrance.

To my intense relief, since coming inside, the worst agony of my unreasonable terror had passed away. If I could only get in some place where I could sit down and be quiet, probably I should be rid of it for good. Determining to try another entrance, I was about to leave the bare hallway when one of several doors along the side of it suddenly opened and a man stepped out into the hall.

“Well?” he said, looking at me keenly, but with not the least show of surprise at my presence.

“I beg your pardon,” I replied. “The door was unlocked and I came in here, thinking it was the entrance to the exhibit — what do they call it? the ‘Great Unseen.’ The one that is mentioned on that long white sign. Can you tell me which door is the right one?”

“I can.”

With that brief answer he stopped and stared at me again. He was a tall, lean man, somewhat stooped, but possessing considerable dignity of bearing. For that neighborhood, he appeared uncommonly well dressed, and his long, smooth-shaven face was noticeable because, while his complexion was dark and his eyes coal-black, above them the heavy brows and his hair were almost silvery-white. His age might have been anything over the threescore mark.

I grew tired of being stared at. “If you can and — won’t, then never mind,” I observed a trifle irritably, and turned to go. But his sharp exclamation halted me.

“No!” he said. “No — no! Forgive me for pausing — it was not hesitation, I assure you. To think that one — one, even, has come! All day they pass my sign up there — pass and fear to enter. But you are different. You are not of these timorous, ignorant foreign peasants. You ask me to tell you the right door? Here it is! Here!”

And he struck the panel of the door, which he had closed behind him, so that the sharp yet hollow sound of it echoed up through the silent house.

Now it may be thought that after all my senseless terror in the open street, so strange a welcome from so odd a showman would have brought the feeling back, full force. But there is an emotion stronger, to a certain point, than fear. This queer old fellow aroused my curiosity. What kind of museum could it be that he accused the passing public of fearing to enter? Nothing really terrible, surely, or it would have been closed by the police. And normally I am not an unduly timorous person. “So it’s in there, is it?” I asked, coming toward him. “And I’m to be sole audience? Come, that will be an interesting experience.” I was half laughing now.

“The most interesting in the world,” said the old man, with a solemnity which rebuked my lightness.

With that he opened the door, passed inward and closed it again — in my very face. I stood staring at it blankly. The panels, I remember, had been originally painted white, but now the paint was flaked and blistered, gray with dirt and dirty finger marks. Suddenly it occurred to me that I had no wish to enter there. Whatever was behind it could be scarcely worth seeing, or he would not choose such a place for its exhibition. With the old man’s vanishing my curiosity had cooled, but just as I again turned to leave, the door opened and this singular showman stuck his white-eyebrowed face through the aperture. He was frowning impatiently. “Come in — come in!” he snapped, and promptly withdrawing his head, once more closed the door.

“He has something there he doesn’t want should get out,” was the very natural conclusion which I drew. “Well, since it can hardly be anything dangerous, and he’s so anxious I should see it — here goes!”

With that I turned the soiled white porcelain handle, and entered.

The room I came into was neither very large nor very brightly lighted. In no way did it resemble a museum or lecture room. On the contrary, it seemed to have been fitted up as a quite well-appointed laboratory. The floor was linoleum-covered, there were glass cases along the walls whose shelves were filled with bottles, specimen jars, graduates, and the like. A large table in one corner bore what looked like some odd sort of camera, and a larger one in the middle of the room was fitted with a long rack filled with bottles and test tubes, and was besides littered with papers, glass slides, and various paraphernalia which my ignorance failed to identify. There were several cases of books, a few plain wooden chairs, and in the corner a large iron sink with running water.

My host of the white hair and black eyes was awaiting me, standing near the larger table. He indicated one of the wooden chairs with a thin forefinger that shook a little, either from age or eagerness. “Sit down — sit down! Have no fear but that you will be interested, my friend. Have no fear at all — of anything!”

As he said it he fixed his dark eyes upon me and stared harder than ever. But the effect of his words was the opposite of their meaning. I did sit down, because my knees gave under me, but if in the outer hall I had lost my terror, it now returned twofold upon me. Out there the light had been faint, dingily roseate, indefinite. By it I had not perceived how this old man’s face was a mask of living malice — of cruelty, hate and a certain masterful contempt. Now I knew the meaning of my fear, whose warning I would not heed. Now I knew that I had walked into the very trap from which my abnormal sensitiveness had striven in vain to save me.

III

Again I struggled within me, bit at my lip till I tasted blood, and presently the blind paroxysm passed. It must have been longer in going than I thought, and the old man must have all that time been speaking, for when I could once more control my attention, hear and see him, he had taken up a position near the sink, about ten feet away, and was addressing me with a sort of “platform” manner, as if I had been the large audience whose absence he had deplored.

“And so,” he was saying, “I was forced to make these plates very carefully, to truly represent the characteristic hues of each separate organism. Now, in color work of every kind the film is necessarily extremely sensitive. Doubtless you are familiar in a general way with the exquisite transparencies produced by color photography of the single-plate type.”

He paused, and trying to act like a normal human being, I observed: “I saw some nice landscapes done in that way — last week at an illustrated lecture in Franklin Hall.”

He scowled, and made an impatient gesture at me with his hand. “I can proceed better without interruptions,” he said. “My pause was purely oratorical.”

I meekly subsided, and he went on in his original loud, clear voice. He would have made an excellent lecturer before a much larger audience — if only his voice could have lost that eerie, ringing note. Thinking of that I must have missed some more, and when I caught it again he was saying:

“As I have indicated, the original plate is the final picture. Now, many of these organisms are extremely hard to photograph, and microphotography in color is particularly difficult. In consequence, to spoil a plate tries the patience of the photographer. They are so sensitive that the ordinary darkroom ruby lamp would instantly ruin them, and they must therefore be developed either in darkness or by a special light produced by interposing thin sheets of tissue of a particular shade of green and of yellow between lamp and plate, and even that will often cause ruinous fog. Now I, finding it hard to handle them so, made numerous experiments with a view of discovering some glass or fabric of a color which should add to the safety of the green, without robbing it of all efficiency. All proved equally useless, but intermittently I persevered — until last week.”

His voice dropped to an almost confidential tone, and he leaned slightly toward me. I was cold from my neck to my feet, though my head was burning, but I tried to force an appreciative smile.

“Last week,” he continued impressively, “I had a prescription filled at the corner drug store. The bottle was sent home to me wrapped in a piece of what I first took to be whitish, slightly opalescent paper. Later I decided that it was some kind of membrane. When I questioned the druggist, seeking its source, he said it was a sheet of ‘paper’ that was around a bundle of herbs from South America. That he had no more, and doubted if I could trace it. He had wrapped my bottle so, because he was in haste and the sheet was handy.

“I can hardly tell you what first inspired me to try that membrane in my photographic work. It was merely dull white with a faint hint of opalescence, except when held against the light. Then it became quite translucent and quite brightly prismatic. For some reason it occurred to me that this refractive effect might help in breaking up the actinic rays — the rays which affect the sensitive emulsion. So that night I inserted it behind the sheets of green and yellow tissue, next the lamp prepared my trays and chemicals laid my plate holders to hand, turned off the white light and — turned on the green!”

There was nothing in his words to inspire fear. It was a wearisomely detailed account of his struggles with photography. Yet, as he again paused impressively, I wished that he might never speak again. I was desperately, contemptibly in dread of the thing he might say next.

Suddenly, he drew himself erect, the stoop went out of his shoulders, he threw back his head and laughed. It was a hollow sound, as if he laughed into a trumpet. “I won’t tell you what I saw! Why should I? Your own eyes shall bear witness. But this much I’ll say, so that you may better understand — later. When our poor, faultily sensitive vision can perceive a thing, we say that it is visible. When the nerves of touch can feel it, we say that it is tangible. Yet I tell you there are beings intangible to our physical sense, yet whose presence is felt by the spirit, and invisible to our eyes merely because those organs are not attuned to the light as reflected from their bodies. But light passed through the screen, which we are about to use has a wave length novel to the scientific world, and by it you shall see with the eyes of the flesh that which has been invisible since life began. Have no fear!”

He stopped to laugh again, and his mirth was yellow-toothed — menacing.

“Have no fear!” he reiterated, and with that stretched his hand toward the wall, there came a click and we were in black, impenetrable darkness. I wanted to spring up, to seek the door by which I had entered and rush out of it, but the paralysis of unreasoning terror held me fast.

I could hear him moving about in the darkness, and a moment later a faint green glimmer sprang up in the room. Its source was over the large sink, where I suppose he developed his precious “color plates.”

Every instant, as my eyes became accustomed to the dimness, I could see more clearly. Green light is peculiar. It may be far fainter than red, and at the same time far more illuminating. The old man was standing beneath it, and his face by that ghastly radiance had the exact look of a dead man’s. Besides this, however, I could observe nothing appalling.

“That,” continued the man, “is the simple developing light of which I have spoken — now watch, for what you are about to behold no mortal man but myself has ever seen before.”

For a moment he fussed with the green lamp over the sink. It was so constructed that all the direct rays struck downward. He opened a flap at the side, for a moment there was a streak of comforting white luminance from within, then he inserted something, slid it slowly in — and closed the flap.

The thing he put in — that South American “membrane” it must have been — instead of decreasing the light increased it — amazingly. The hue was changed from green to greenish-gray, and the whole room sprang into view, a livid, ghastly chamber, filled with — overcrawled by — what?

My eyes fixed themselves, fascinated, on something that moved by the old man’s feet. It writhed there on the floor like a huge, repulsive starfish, an immense, armed, legged thing, that twisted convulsively. It was smooth, as if made of rubber, was whitish-green in color; and presently raised its great round blob of a body on tottering tentacles, crept toward my host and writhed upward — yes, climbed up his legs, his body. And he stood there, erect, arms folded, and stared sternly down at the thing which climbed.

But the room — the whole room was alive with other creatures than that. Everywhere I looked they were — centipedish things, with yard-long bodies, detestable, furry spiders that lurked in shadows, and sausage-shaped translucent horrors that moved — and floated through the air. They dived — here and there between me and the light, and I could see its bright greenness through their greenish bodies.

Worse, though; far worse than these were the things with human faces. Mask-like, monstrous, huge gaping mouths and slitlike eyes — I find I cannot write of them. There was that about them which makes their memory even now intolerable.

The old man was speaking again, and every word echoed in my brain like the ringing of a gong. “Fear nothing! Among such as these do you move every hour of the day and night. Only you and I have seen, for God is merciful and has spared our race from sight. But I am not merciful! I loathe the race which gave these creatures birth — the race which might be so surrounded by invisible, unguessed but blessed beings — and chooses these for its companions! All the world shall see and know. One by one shall they come here, learn the truth, and perish. For who can survive the ultimate of terror? Then I, too, shall find peace, and leave the earth to its heritage of man-created horrors. Do you know what these are — whence they come?”

This voice boomed now like a cathedral bell. I could not answer, him, but he waited for no reply. “Out of the ether — out of the omnipresent ether from whose intangible substance the mind of God made the planets, all living things, and man — man has made these! By his evil thoughts, by his selfish panics, by his lusts and his interminable, never-ending hate he has made them, and they are everywhere! Fear nothing — but see where there comes to you, its creator, the shape and the body of your FEAR!”

And as he said it I perceived a great Thing coming toward me — a Thing — but consciousness could endure no more. The ringing, threatening voice merged in a roar within my ears, there came a merciful dimming of the terrible, lurid vision, and blank nothingness succeeded upon horror too great for bearing.

IV

There was a dull, heavy pain above my eyes. I knew that they were closed, that I was dreaming, and that the rack full of colored bottles which I seemed to see so clearly was no more than a part of the dream. There was some vague but imperative reason why I should rouse myself. I wanted to awaken, and thought that by staring very hard indeed I could dissolve this foolish vision of blue and yellow-brown bottles. But instead of dissolving they grew clearer, more solid and substantial of appearance, until suddenly the rest of my senses rushed to the support of sight, and I became aware that my eyes were open, the bottles were quite real, and that I was sitting in a chair, fallen sideways so that my cheek rested most uncomfortably on the table which held the rack.

I straightened up slowly and with difficulty, groping in my dulled brain for some clue to my presence in this unfamiliar place, this laboratory that was lighted only by the rays of an arc light in the street outside its three large windows. Here I sat, alone, and if the aching of cramped limbs meant anything, here I had sat for more than a little time.

Then, with the painful shock which accompanies awakening to the knowledge of some great catastrophe, came memory. It was this very room, shown by the street lamp’s rays to be empty of life, which I had seen thronged with creatures too loathsome for description. I staggered to my feet, staring fearfully about. There were the glass-floored cases, the bookshelves, the two tables with their burdens, and the long iron sink above which, now only a dark blotch of shadow, hung the lamp from which had emanated that livid, terrifically revealing illumination. Then the experience had been no dream, but a frightful reality. I was alone here now. With callous indifference my strange host had allowed me to remain for hours unconscious, with not the least effort to aid or revive me. Perhaps, hating me so, he had hoped that I would die there.

At first I made no effort to leave the place. Its appearance filled me with reminiscent loathing. I longed to go, but as yet felt too weak and ill for the effort. Both mentally and physically my condition was deplorable, and for the first time I realized that a shock to the mind may react upon the body as vilely as any debauch of self-indulgence.

Quivering in every nerve and muscle, dizzy with headache and nausea, I dropped back into the chair, hoping that before the old man returned I might recover sufficient self-control to escape him. I knew that he hated me, and why. As I waited, sick, miserable, I understood the man. Shuddering, I recalled the loathsome horrors he had shown me. If the mere desires and emotions of mankind were daily carnified in such forms as those, no wonder that he viewed his fellow beings with detestation and longed only to destroy them.

I thought, too, of the cruel, sensuous faces I had seen in the streets outside — seen for the first time, as if a veil had been withdrawn from eyes hitherto blinded by self-delusion. Fatuously trustful as a month-old puppy, I had lived in a grim, evil world, where goodness is a word and crude selfishness the only actuality. Drearily my thoughts drifted back through my own life, its futile purposes, mistakes and activities. All of evil that I knew returned to overwhelm me. Our gropings toward divinity were a sham, a writhing sunward of slime —— covered beasts who claimed sunlight as their heritage, but in their hearts preferred the foul and easy depths.

Even now, though I could neither see nor feel them, this room, the entire world, was acrawl with the beings created by our real natures. I recalled the cringing, contemptible fear to which my spirit had so readily yielded, and the faceless Thing to which the emotion had given birth.

Then abruptly, shockingly, I remembered that every moment I was adding to the horde. Since my mind could conceive only repulsive incubi, and since while I lived I must think, feel, and so continue to shape them, was there no way to check so abominable a succession? My eyes fell on the long shelves with their many-colored bottles. In the chemistry of photography there are deadly poisons — I knew that. Now was the time to end it — now! Let him return and find his desire accomplished. One good thing I could do, if one only. I could abolish my monster-creating self.

V

My friend Mark Jenkins is an intelligent and usually a very careful man. When he took from “Smiler” Callahan a cigar which had every appearance of being excellent, innocent Havana, the act denoted both intelligence and caution. By very clever work he had traced the poisoning of young Ralph Peeler to Mr. Callahan’s door, and he believed this particular cigar to be the mate of one smoked by Peeler just previous to his demise. And if, upon arresting Callahan, he had not confiscated this bit of evidence, it would have doubtless been destroyed by its regrettably unconscientious owner.

But when Jenkins shortly afterward gave me that cigar, as one of his own, he committed one of those almost inconceivable blunders which, I think, are occasionally forced upon clever men to keep them from overweening vanity. Discovering his slight mistake, my detective friend spent the night searching for his unintended victim, myself; and that his search was successful was due to Pietro Marini, a young Italian of Jenkins’ acquaintance, whom he met about the hour of 2:00 A.M. returning from a dance.

Now, Marini had seen me standing on the steps of the house where Doctor Frederick Holt had his laboratory and living rooms, and he had stared at me, not with any ill intent, but because he thought I was the sickest-looking, most ghastly specimen of humanity that he had ever beheld. And, sharing the superstition of his South Street neighbors, he wondered if the worthy doctor had poisoned me as well as Peeler. This suspicion he imparted to Jenkins, who, however, had the best of reasons for believing otherwise. Moreover, as he informed Marini, Holt was dead, having drowned himself late the previous afternoon. An hour or so after our talk in the restaurant, news of his suicide reached Jenkins.

It seemed wise to search any place where a very sick-looking young man had been seen to enter, so Jenkins came straight to the laboratory. Across the fronts of those houses was the long sign with its mysterious inscription, “See the Great Unseen,” not at all mysterious to the detective. He knew that next door to Doctor Holt’s the second floor had been thrown together into a lecture room, where at certain hours a young man employed by settlement workers displayed upon a screen stereopticon views of various deadly bacilli, the germs of diseases appropriate to dirt and indifference. He knew, too, that Doctor Holt himself had helped the educational effort along by providing some really wonderful lantern slides, done by micro-color photography.

On the pavement outside, Jenkins found the two-thirds remnant of a cigar, which he gathered in and came up the steps, a very miserable and self-reproachful detective. Neither outer nor inner door was locked, and in the laboratory he found me, alive, but on the verge of death by another means that he had feared.

In the extreme physical depression following my awakening from drugged sleep, and knowing nothing of its cause, I believed my adventure fact in its entirety. My mentality was at too low an ebb to resist its dreadful suggestion. I was searching among Holt’s various bottles when Jenkins burst in. At first I was merely annoyed at the interruption of my purpose, but before the anticlimax of his explanation the mists of obsession drifted away and left me still sick in body, but in spirit happy as any man may well be who has suffered a delusion that the world is wholly bad — and learned that its badness springs from his own poisoned brain.

The malice which I had observed in every face, including young Marini’s, existed only in my drug-affected vision. Last week’s “popular-science” lecture had been recalled to my subconscious mind — the mind that rules dreams and delirium — by the photographic apparatus in Holt’s workroom. “See the Great Unseen” assisted materially, and even the corner drug store before which I had paused, with its green-lit show vases, had doubtless played a part. But presently, following something Jenkins told me, I was driven to one protest. “If Holt was not here,” I demanded, “if Holt is dead, as you say, how do you account for the fact that I, who have never seen the man, was able to give you an accurate description which you admit to be that of Doctor Frederick Holt?”

He pointed across the room. “See that?” It was a life-size bust portrait, in crayons, the picture of a white-haired man with bushy eyebrows and the most piercing black eyes I had ever seen — until the previous evening. It hung facing the door and near the windows, and the features stood out with a strangely lifelike appearance in the white rays of the arc lamp just outside. “Upon entering,” continued Jenkins, “the first thing you saw was that portrait, and from it your delirium built a living, speaking man. So, there are your white-haired showman, your unnatural fear, your color photography and your pretty green golliwogs all nicely explained for you, Blaisdell, and thank God you’re alive to hear the explanation. If you had smoked the whole of that cigar — well, never mind. You didn’t. And now, my very dear friend, I think it’s high time that you interviewed a real, flesh-and-blood doctor. I’ll phone for a taxi.”

“Don’t,” I said. “A walk in the fresh air will do me more good than fifty doctors.”

“Fresh air! There’s no fresh air on South Street in July,” complained Jenkins, but reluctantly yielded.

I had a reason for my preference. I wished to see people, to meet face to face even such stray prowlers as might be about at this hour, nearer sunrise than midnight, and rejoice in the goodness and kindliness of the human countenance — particularly as found in the lower classes.

But even as we were leaving there occurred to me a curious inconsistency.

“Jenkins,” I said, “you claim that the reason Holt, when I first met him in the hall, appeared to twice close the door in my face, was because the door never opened until I myself unlatched it.”

“Yes,” confirmed Jenkins, but he frowned, foreseeing my next question.

“Then why, if it was from that picture that I built so solid, so convincing a vision of the man, did I see Holt in the hall before the door was open?”

“You confuse your memories,” retorted Jenkins rather shortly.

“Do I? Holt was dead at that hour, but — I tell you I saw Holt outside the door! And what was his reason for committing suicide?”

Before my friend could reply I was across the room, fumbling in the dusk there at the electric lamp above the sink. I got the tin flap open and pulled out the sliding screen, which consisted of two sheets of glass with fabric between, dark on one side, yellow on the other. With it came the very thing I dreaded — a sheet of whitish, parchmentlike, slightly opalescent stuff.

Jenkins was beside me as I held it at arm’s length toward the windows. Through it the light of the arc lamp fell — divided into the most astonishingly brilliant rainbow hues. And instead of diminishing the light, it was perceptibly increased in the oddest way. Almost one thought that the sheet itself was luminous, and yet when held in shadow it gave off no light at all.

“Shall we — put it in the lamp again — and try it?” asked Jenkins slowly, and in his voice there was no hint of mockery.

I looked him straight in the eyes. “No,” I said, “we won’t. I was drugged. Perhaps in that condition I received a merciless revelation of the discovery that caused Holt’s suicide, but I don’t believe it. Ghost or no ghost, I refuse to ever again believe in the depravity of the human race. If the air and the earth are teeming with invisible horrors, they are not of our making, and — the study of demonology is better let alone. Shall we burn this thing, or tear it up?”