8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: anna ruggieri

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

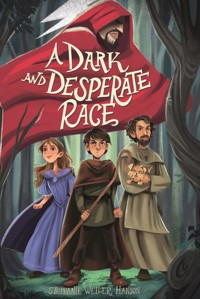

Cover

Title page

by Stephanie Weller Hanson

Copyright page

Library of Congress Control Number: 2024945098

ISBN 10: 0-8198-3467-XISBN 13: 978-0-8198-3468-3

Cover art and design and interior art by Rafaela Villela

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

“P” and PAULINE are registered trademarks of the Daughters of St. Paul.

Copyright © 2025, Stephanie Weller Hanson

Published by Pauline Books & Media, 50 Saint Pauls Avenue, Boston, MA 02130-3491

eBook by ePUBoo.com

www.pauline.org

Pauline Books & Media is the publishing house of the Daughters of St. Paul, an international congregation of women religious serving the Church with the communications media.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

29 28 27 26 25

Dedication

for my father

for Bruce

Contents

Map

“The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.”

Chapter 1

Father

“Didn’t try very hard, did you?” There was acid in Father’s voice as he looked over Will’s work, his first two pages of sums on the ledgers for the weaving room.

“I did try,” said Will.

“He’s worked every weeknight for the entire month that you were gone in the south,” said Mother.

Father turned to her, his voice sharp. “What makes you so sure of that?”

Will was surprised. Father often used that tone with him, but he rarely spoke to Mother that way. She rose, her eyes blazing.

“Because I sat with him in this room every single night, Hugh!”

That brought Father up short for a moment. He stopped and rubbed his hand over his face and knuckled his eyes with his fists. He was a short man, with a balding head of brown hair and an intense face. Will saw Mother take a deep breath. She came over to Father and put a hand on his arm.

“Hugh, you just arrived home from a long journey. I can see how tired you are. Let this wait for the morrow.” It was her commonsense tone, and Father usually listened to her. But tonight, he held up a hand and leaned over the ledger again.

“Just checking the boy’s addition. I won’t be long.” And he began to study the next page of entries. Will’s father was amazingly clever with numbers. He always got the right sum in his head, even with a long column of figures. Will wished for the thousandth time that he had the same talent. “Two and two make four,” he was always saying to Will. “Eight and eight make sixteen. Numbers are dependable. They don’t change.”

Will wanted to believe him, but when he sat down with the ledgers, he turned numbers around or he got the wrong sum across, so that the downward total didn’t match, and he had to begin again. Numbers seemed to slip through his fingers like so many little fish until he was nearly sure that twos turned into threes, and sevens curled into eights, and two and two just might make five.

On this page, though, Will knew he’d gotten it correct.

“Right,” said Father shortly, and he turned to the next pages. “And these?”

Father went on totaling up numbers on the second page, then the next. Will could see thunder growing in his face. His brows contracted into a single hard line. His face turned crimson.

“Wrong and wrong again!” he yelled, and he pounded his fist on the worktable. “You haven’t learned a thing! You’ll never change. You’re just stupid—or lazy—or both!”

Will stumbled back from the worktable. He felt hot from head to toe. Father had never said that before.

“Please, Hugh!” said Mother. “You know that numbers are difficult for him!”

Father turned to Will. “You turned fourteen in March. Nearly a man. You’ve had schooling from both Master Wimbourne and me on the ledgers. You know the farm and the flocks well enough, but the weaving room, boy! The records we keep are the key to making the weaving room thrive!”

Will usually tried to placate Father when he got angry, but tonight’s argument was worse than any he could remember. And he had worked so hard! Now a fire was building in him, and words were burning to be let out.

If he says I’m lazy or stupid, he must hate me!

Father straightened his shoulders. “Well, this shows that I made the right decision about the summer.”

“What?” said Will. He glanced over. Mother looked confused, too.

“Patch can take young Walter up to the high meadows with the flocks. You are going to spend the summer in the workroom with me. You’re going to work on these ledgers until you get them right.”

Will’s stomach dropped to his toes. “No, I … but …” Why couldn’t he ever come up with the right words in an argument?

“Hugh, we must speak about this in private!” Mother’s voice was urgent.

Father shook his head. “Made up my mind on the journey home, Margaret.” He pointed a finger at Will. “You’ve put in time on the ledgers, but look how much good it did you. Haven’t learned a thing!”

It’s like being sentenced to prison. He’ll be on me every minute of the day.

“But, Father, I have to go up to the high meadows with Patch and the dogs!”

“Made your own bed and now you’ll lie in it,” snapped Father.

“Hugh, stop!” said Mother.

He turned to her. “You don’t understand, Margaret. Since Richard and Thomas left, I bear the burden of running this farm and weaving room alone.”

“Alone?!” exclaimed Mother, and Will could hear how offended she was. She worked as hard as Father did. But Father was not done. He turned back to Will.

“It’s your own fault! Your brothers had no trouble with numbers. Thomas and Richard both had brains enough.”

That was it. All the words he’d been holding in spewed out.

“Brains enough, yes!” he shouted back. “They had brains enough to get away from the Meadows, to get away from you!”

He saw shock register in Father’s face.

“Will!” said Mother, stricken.

Everything stopped as they stared at one another.

“You, you ungrateful, hard-hearted, spiteful—!”

“Hugh, stop!” Mother begged.

“Enough is enough! I’m done with you, boy! Riggwelt! I’d rather teach a lamb to dance on a fence post than spend one more minute with you!” He strode out of the room, slamming the door behind him.

“Will, please …” Mother began.

Will stalked over to the worktable and, with one great sweep of his arm, swept papers, ledgers, quill, and ink onto the floor.

“Wait!” Mother called, but Will ran out the door and out of the house. In the barn, he surged up the ladder two rungs at a time to the haymow and threw himself in the hay.

I can’t take this anymore! I can’t take one more minute of him yelling at me! I’ve had enough. He hates me, and I hate him back! He might as well beat me with his fists. He’s been beating on me with his words, watching me for every mistake for more than a year. I’ve got to get out of here!

He stopped, breathing hard.

Leaving.

He was thinking about leaving. A tremor passed through him. He would hurt Mother dreadfully. He would miss the Meadows, and Patch, and when would he ever see Richard?

But what choice do I have? I cannot stay around Father! I can herd sheep or work in a stable. I’ll have to take Perk to get some distance from home, where people won’t know the Pennington name. I’ll leave a letter for Mother, telling her what I’m doing, so she won’t worry. It’s the only way.

He lay there, picturing it, making a mental list of all the things he needed to do, even what food he could take. He realized that he couldn’t prepare for everything tomorrow. It would have to be the day after. He closed his eyes fretfully, feeling the weight of his plan.

He woke before dawn and lay listening to the animals for a few seconds. Then the fight with Father rushed back on him, and his mood plummeted. He climbed down from the loft, went over to Perk, and wrapped his arms around his horse’s neck.

“Are you ready for a ride, Perk? A long one? It’ll be just you and me, but I promise to take good care of you.” Perk nickered in his arms. Will began to groom him carefully. Who knew when they would next be in a stable where such niceties would be available?

Once dawn came, he sat out of sight of the house and barn up on his watching rock. Richard had shown him the rock when he was little. And he had used it the same way Richard and Thomas did before him—to hide when somebody wanted them for chores. From here, he could see the whitewashed face of the barn and the weaving room and the edge of the house on this side, with the well and the watering trough in the middle of the yard. Workers were spreading out to their various chores. He saw Father cross to the weaving room. That was a relief; he’d be there all day and into the evening, likely.

It was mid-morning, and he had yet to cross the threshold of the house. He stood at the edge of the pond behind the worker’s houses, hungry, bleary-eyed and half sick. He picked up a stone and, with an angry flick of his wrist, sent it skipping across the surface of the water.

He looked up the slope and beyond, to the high peaks. He knew just the kind of day it would be up there. The vivid blue sky, a sharp, cool wind in the pines, the meadows ablaze with flowers, the silence and the space of it, the new lambs kicking all four feet in the air. That part of the Meadows he loved.

He snapped off another stone. It pinged once, then dropped with a resounding plop into the water. And he loved the animals. He had the way with creatures, as Mother did. Only they could milk old Stella Maris, the crankiest cow in the herd, who would kick anyone else. For all Father’s competence and knowledge about the flocks, that was one Northern knack he did not have. With a snap that hurt his wrist, Will spun out another stone. The rock pinged four times across the surface like a ball shot from a musket.

“An island you’ll build out there if you’re not careful,” said a familiar voice behind him.

Will didn’t turn around. For the last two years, Patch, the elderly chief shepherd, had been teaching him the fine points of herding.

I will miss him, he thought, and then, swallowing the sudden lump in his throat, he said, “Have I thrown that many?”

“Aye,” said the old man. “In the last three year.”

“It’s your fault. You taught me.” Will leaned down for more stones.

The old man sucked hard on his pipe. “Nay. Your father taught you six summers ago when you was eight, right before he opened the weaving room.”

Will sent out another stone. It plunked into the water. How had he forgotten? A terrible fever had swept through the southern portions of Lindenhelm, and Mother had gone to nurse her sick sister. He’d missed her terribly. In the evenings, Father had taught Thomas, Richard, and him how to skip stones. He could almost feel Father’s hand guiding his. The memory seemed to dig out an empty place inside him. Father had been nicer then. Why had everything changed? What had he done wrong?

Egil, the apprentice weaver, came around the corner of the cottages. “Master bids you come,” he said.

Patch stood up. Will bent down to get another stone, sorry to lose Patch. Then, to his dismay, he saw Egil waiting for him.

“Master bids you come,” Egil repeated.

I can’t.

“You’d best come,” said Patch. “’Tis urgent, lad.”

With lagging steps, he followed Patch and Egil into the yard. He came into the weaving room with its busy looms, their treadles going smoothly back and forth, tuck-tuck, tuck-tuck, and the gorgeous array of yarns on the walls.

It’ll be awful looking Father in the face. What should I say? Will he even talk to me?

From the door to Father’s work room, Patch looked back. “Best not dawdle.”

Will caught up with him in two quick strides. “Do you know what he wants?”

Patch nodded and reached out to knock.

Will stayed his hand. “Tell me what it is.”

Patch’s gaze rested on him. “’Tis not another chiding, lad.”

Will felt a flush travel up his cheeks. Patch knocked.

“Enter,” called Father.

Chapter 2

Plans Laid In

The door opened, and Will let out a delighted whoop and threw himself at his older brother.

“Richard! What are you doing here? Where’s your regiment? You’re supposed to be down in Sarrow, aren’t you? Why didn’t you tell us you were coming?”

“Whoa, little brother!” Richard laughed and held him at arm’s length.

Will looked at his brother with a mixture of love, admiration, and envy. In the eighteen months he’d been gone, Richard had filled out. He was broader at the shoulders and thicker at the arms, more like Father every day. Will, who scorned his own thin frame, wondered if he would ever look like that. Richard surveyed him critically, then pulled a strand of hay out of Will’s hair.

“Been napping in the haymow again, have we?” he said.

Will flushed, and Father turned to stare at him. He looked more tired than ever and still angry. Will felt his cheeks burn, but he would not be the first one to speak.

Richard looked from one of them to the other. “Um … you’ll be happy to know, little brother, that we’ll be stationed just south of Twelve Trees through July.” He turned to Father. “Strange, too. The orders came only hours before we were to leave for Sarrow, and from the king himself, I heard.”

“Sit,” Father said sharply. Will saw Richard’s eyes widen. Father must have realized how he sounded. He glanced at Richard and said, “Sit here, Richard. Patch, you take my chair.”

Patch sat down and took out his pipe. Will found a stool in the corner and pulled it over. Then he jumped back. Father stood toe to toe with him.

“You’re here, boy, because your mother begged me. A mistake, but I gave in to her.”

Will forced himself to return Father’s gaze. All the anger from last night surged up inside him. He would not—would not—be cowed, especially in front of Richard.

“Listen and keep your mouth shut. Do you understand?”

“Father!” Richard’s voice was an entreaty. “I’m sure Will can listen to whatever you have to say.”

Father sighed. “You’ve been gone from home a while, Richard. Things have changed here.” He glowered at Will again before he sat down.

Will stared at the floor, his cheeks hot, anger simmering in him.

“Two problems,” Father said, then he halted. All of them, by long habit, waited while Father found the words he wanted. “First is the scours.”

Will sat up. Scours was a sheep disease, an uncontrollable black diarrhea. It could kill lambs in two days, the strongest sheep in three. Three years ago, when the flocks had scours, he’d helped Mother with the dosing. They’d lost seventeen that time.

“When did it start? How many are sick?” he asked.

“This morning. Two ewes, four lambs,” said Father.

“And we’re low on herbs,” said Patch. “Mistress says we need more by Wednesday midday.”

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)