Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bluemoose Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

It is a story about journeys. Ben travels from London by train to a small German island to see his famous friend Pascal. As he travels, Ben listens to voice notes from Pascal, each relating to a photograph from a different moment in his life. The messages tell the story of family, of migration, of exile and the search for home in a fractured world.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 292

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

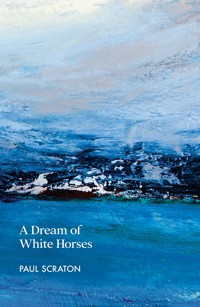

A Dream of White Horses

By Paul Scraton

Imprint

Copyright © Paul Scraton 2024

First published in 2024 byBluemoose Books Ltd25 Sackville StreetHebden BridgeWest YorkshireHX7 7DJ

www.bluemoosebooks.com

All rights reservedUnauthorised duplication contravenes existing laws

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication dataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

PaperbackISBN 978 1 915693 20 4

Printed and bound in the UK by Short Run Press

Dedication

For Tom

Part One

I.

A city scene, viewed from the centre of the street. On either side, six-storey houses, all the same height and yet each with their own character. Some feature elaborate stucco work around the windows. Others have tall entranceways, high enough to accommodate a horse-drawn carriage. There are houses with balconies bolted on to the exterior walls, space for bicycles or boxes of herbs and tomatoes beside small tables and fold-out chairs. At the end of the street the sun hangs low in the sky, casting long shadows. On the pavement a person walks away, a slim silhouette. They wear a long coat that falls down to the back of their knees. No further identifying features.

A hillside of beech trees, their trunks standing tall above a thick layer of leaves on the ground. It is late winter, or early spring. Between the trees black wooden crosses have been hammered into the ground. There is no obvious pattern. A cluster of four, over to the left. A number of pairs. Some stand solitary, leaves bunched at their base. Altogether there are seventeen in view. Seventeen black crosses, although there is a sense that there are more, many more, just out of sight.

A close-up of a gateway of smooth stone, two sides of a corner. To the left, a ghostly sign on the brickwork, the letters faded. It is not possible to read them all, but they suggest that there was once a coal dealer here, a certain P.A. SCH––––, with an arrow directing potential customers to the back courtyard. To the right, a brand new brass plaque, all the letters carefully engraved. JOHANNSSEN. ARCHITECTURE + DESIGN BUREAU. Polished: the sign shines in the sun.

A sandy trail through the woods. Tall pines against a bleached sky. The only branches are at the top, far above the forest floor. The path undulates but maintains a straight line between the trees, and at the top of one of the rises stands an oak tree. It is thick, solid. Standing here since long before the pines were planted.

A prison cell, four metres by two. A concrete bed and a barred window, a built-in toilet in the corner. At the centre of the room stands an exhibition display, a soft surface framed by a thin sliver of silver metal, onto which a banner has been pinned. Words of protest, painted on a bed sheet.

A basketball court, empty except for a two-tone ball and discarded soft drink can. Beyond the fence a wide river flows, with a dense forest on the opposite bank, like in a fairy tale. On the river a barge travels against the current, laden with identical cars.

A sand dune out of which tall grass sparsely grows. Beyond, the beach, the sea and the sky. It is impossible to make out the exact place where one meets the other. Wave breakers reach out towards the horizon in straight rows, but today the water is glassy, calm.

A fragmented headstone in three pieces. The visible letters come from the Latin and Hebrew alphabets. Around them, early springtime flowers push their way up through the frosted ground.

A single track railway line. On either side, fir trees lean in over the tracks in the mist, fading in shades to a white centre where nothing can be seen.

Black.

*****

The applause starts quietly, a little hesitant as if we are all waiting for something to happen. Then it rises, like the sound of an approaching train as Pascal’s name appears in the centre of the screen. There are about a hundred people in this darkened, windowless room, tucked away in the basement of a London hotel, and they are all applauding my friend. They continue for a while, eyes peering through the darkness to see if they can spot someone who might be him, in case he might be here, listening to their appreciation in this function room with its soft carpets and abstract pastel prints spaced out on the wall. I am concentrating on the moment. Taking it all in, committing as many details as possible to memory, for my friend is not here and I want to be able to tell him as much as I can about what happened when the last of his photographs faded to black and his name appeared on the screen.

Beside the screen a spotlight is turned on, creating a pool of light around a microphone and a slender lectern. A man steps into the light with a piece of paper in his hand. He’s wearing jeans and a shirt; his tie is the work of someone who presumably doesn’t wear one very often. He looks down at the paper before he begins to speak. The room has stopped clapping now, as we wait to hear what he has to say.

He begins, after a final sip of water, by thanking us all for coming, for taking the time to join him and his colleagues in this celebration of Pascal and his work. He talks about the photographs we have seen and the project they were part of, listing the exhibitions hosted by galleries and museums across Europe, and the publishers of the book, who have also joined us tonight. He explains that it is with sadness he has to announce that Pascal cannot be with us for this moment of tribute. He does not give a reason why, but nevertheless he is sure that Pascal will be delighted to hear how many people braved the miserable weather to come out tonight. The man pauses, perhaps because of stage directions scribbled in his notes, and to his obvious relief there are some in the audience who oblige with gentle laughter. He continues with what is his final line, a parade of clauses building to a climax and the sound of applause once more, and I realise it is my cue, that it is time for me to push back my chair and make my way through the tables towards the light.

II.

Drizzle falls on the Euston Road as I switch my bag from one shoulder to the other, standing in the doorway of a pub to check the time on my phone. Noon. Pascal’s award is too big to fit in my bag, so I’ve had to carry it in my hands. It’s a square, glass-like object with a hole through the centre. I’m not sure what it is supposed to represent, but at least it is easy to hold. Water is speckled on the surface from the short walk between the underground station exit and this doorway, and so I wipe it with my sleeve as I look out across the street, through the misting rain and the steady flow of cars, buses and taxis. The sound of a wet road in England is different to where I live now. It must be something to do with the road surfaces, or maybe even the vehicles themselves.

Once I left the country of my childhood I realised those differences were everywhere: in the shape of the street furniture and the painted lines by the side of the road, the strength and colour of the light cast by the streetlamps or the sound of the ambulance sirens as they bounced between the buildings. Of course, every place looks different to another, but I hadn’t realised how they sounded different too, and that these two things were connected. We experience a city because of the long story of how it came to be, how it shaped the layout of the streets or the site of the buildings, the present day an end point of a long and individual story. And now, when I return to London or Liverpool, Manchester or Leeds, I find that to rediscover those elements that make a place look and sound as it does is to trigger memories of my own story, many of which I am surprised are still there.

The walk home from football training, legs muddy beneath scratchy school trousers because the changing room showers were broken. The wait for slow drinkers on a university pub crawl, standing on the street between the picnic tables and the bus stop, a night out often attempted but never completed, because halfway through we reached the end of our road and we were drunk enough already. The time here, in London, on a hot summer evening, outside on the steps of a closed laundrette, beers in plastic pint pots, talking with Pascal as it slowly went dark and the streetlamps flickered on above where we sat.

A bus moves through a puddle that has grown above an overwhelmed drain and so I step back, further into the doorway, even though the spray is a long way from reaching me. I use my phone to take a picture and record a snippet of sound. I will send them to Pascal later. He asked me to document the trip. The details were important, he said. The moments of waiting. In all his travels, they were often the experiences that lingered longest.

There is still an hour until my train and the drizzle has turned to rain. The pub door opens and a man pushes past me, stepping out to stand beneath the sodden awning to smoke his cigarette. I feel the warmth of the pub’s interior as the door swings, the smell of air freshener and long-spilled beer. Another one of those moments. I step inside.

The pub is quite empty, a cavernous room of patterned carpets and wooden furniture, raised sections and fruit machines by the toilet doors. There are menus on every table and a long line of beer taps behind the bar. It’s a place to grab a drink and a bite to eat after work or while waiting for the train, and on this Sunday lunchtime there are only solitary men, sitting with cups of coffee and their phones, and a small group of football fans who came down on the early train, the rain driving them into the first pub they came to outside the station. They are gathered around a stand-up table close to the bar and nurse their beers. Kick-off is still a good few hours away.

I take my pint to a table in the corner by the door, and put it down alongside Pascal’s award, my bag tucked away beneath my chair at my feet. Having served me, the barman has come out into the room and is moving from table to table with a collection of wooden boxes, each filled with cutlery and condiments.

‘What’s this?’ the barman says as he reaches me, looking down at the plastic shape next to my pint glass. I tell him about Pascal and his photographs, about how he had asked me to come to London and collect it, and that I was now about to deliver it to him. The barman is having a quiet shift and seems eager to talk. He wants to know where Pascal is now and, when I tell him, I am surprised that he has heard of the island, that he nods in recognition when I say its name. He was there once, the barman says, or at least on the mainland, from where he could see the island low on the horizon from the top of the dunes. It was a church trip, years ago, and they had slept in huge tents a short walk from the beach. Not that he ever went to church any more, he continues, stumbling slightly over his words, his demeanour changing as if he is suddenly aware of what it is he is saying, out loud and to a customer, to a stranger. It was nice there, he says, a little helplessly now. What he remembers most was the view from the top of the dunes, when he would climb up there in the morning and look out across the sea. That, and the fact that there were no tides.

He stops and looks at me, waiting for a response. I tell him about the train, about how I arrived only yesterday at St Pancras and that I am already leaving again, retracing my journey home and then on to the island. The barman has recovered his composure and shakes his head.

‘If it was me,’ he says, rearranging a couple of sachets of brown sauce in the wooden box on the table between us, ‘I’d just fly. Climate change or not.’

I just nod. He gives me a small smile, and then he moves on. I don’t tell him that I didn’t feel like I had much of a choice, that from the moment Pascal asked me to do this, it was clear I was going to be taking the train. It wasn’t that Pascal insisted, or even asked about my travel arrangements, it was just that I knew how he would have come if he could, and so it felt only right for me to do the same. And in any case, he’d given me more than enough to do to fill the time along the way.

As time passes it feels like you can become increasingly close to some people who you never, or hardly ever, get to see. The major beats of life are shared and distributed, liked and commented upon. Subtle changes of appearance, of hair colour and length, of the ageing process, are unconsciously absorbed. Relationships and birthdays, new jobs and a new flat. People might lose touch, but they don’t lose track. In the fifteen years between my leaving England and the house I’d shared with Pascal in Leeds, to the evening in London when he came back into my life properly again, I’d seen him in person only twice. Once in Rotterdam, when we both happened to be there for work at the same time. Once in Landeck, in Austria, when we were close enough to meet each other halfway. Those meetings amounted to perhaps five hours together in total. Five hours in fifteen years. And yet thanks to the pictures and posts, the emails and messages, it never felt like we had to play catch up. It never really felt like we’d been apart.

When we met in London, something changed. As we sat by the Kingsland Road and watched the rush hour traffic stream by, I already felt that it would not be another four or five years before we saw each other again. I was in the city for work, for a series of meetings that kept me busy throughout the day but which finished close to a small bookshop near Pascal’s flat. It was one of those July days when the heat was such that the road melted beneath the tires of the buses and the air was thick enough to be both energy sapping and yet dense enough to hold a person upright in its warm embrace. We met outside the bookshop and then walked down to the pub on the corner, where all the tables outside were full and the drinkers spilled down the pavement, sitting where they could. I’d bought Pascal a book, a present that I thought he might like, and he accepted it with grace but warned me that he would give it away as soon as he was finished, so I shouldn’t write anything inside the cover. I knew what he was like, he said with a shrug, and I did, which was why I hadn’t scribbled a message in the book in the first place.

Pascal had always been one to live out of a suitcase. Or a rucksack. Or an old, heavy cardboard box, salvaged from the supermarket. As long as it could be transported on a train or a bus. When we lived together in that house in Leeds, there was nearly nothing there that belonged to Pascal, even though it was his name on the contract and it was to him that the rest of us paid the rent. It was crucial, he said, not to have too much stuff, too many things. You had to be able to carry everything that was important to you. When he left, in his car or on the train, travelling for work as he often did, he took with him everything that was important, as if he might never come back. For the time he was gone, it was like the rest of us in the house were living with a ghost.

I had friends at the time who doubted whether Pascal existed, such was his complete absence in those days and weeks when he was away, photographing a football tournament or a test match, a cycling tour or a rowing regatta. One of our flatmates once asked him, when he explained his philosophy of belongings to her, what it was that he thought was going to happen. What terrible event, she said, was he constantly prepared for? Pascal smiled and simply said that being able to up and leave at any time was not necessarily in anticipation of something bad happening. There were other possibilities too.

That evening in London, sitting on the laundrette steps, we shared a few memories and filled in some gaps, but otherwise we talked little about the past. We didn’t need to. As I had realised in Amsterdam and in Austria, time created no distance with Pascal. It simply bent back to let us continue from where we left off.

I first met Pascal in the house on Richmond Mount that we would come to share, having seen an advert for a room in the window of a newsagents on Hyde Park corner. Pascal let me into the house, briefly showed me the living room, the kitchen and the room that would be mine. He asked me a few questions about what I was doing in Leeds while giving me the feeling he wasn’t really interested in the answers, and then suggested we went for a walk. We walked from Headingley, past the cricket ground to where the land falls away towards the river, the slopes lined with steep terraces that run down towards the main road, the railway line and the supermarkets and cinemas that occupied the valley floor. Pascal was leading, and we were walking to Kirkstall Abbey, although I didn’t know what the destination was going to be until we got there. Once we arrived we wandered the grounds amidst the remains of the Abbey, the sun shining through the gaps in the soot-blackened Yorkshire stone. It had been a ruin, Pascal told me, longer than it had ever been a working abbey, and that was perhaps the key to its longevity. We like ruins better than we like our buildings intact, he said, taking a small camera out of his shoulder bag.

We strolled through the grounds as Pascal took photographs. He asked me questions as we went, about my family and my friends, about girlfriends and what I daydreamed of when sitting in the lecture halls of the university. I answered them all, but asked no questions of my own, mainly because he seemed to be so concentrated on his photographs. He seemed happy to let me talk, to provide the background noise to his work, which he was taking very seriously despite the fact that all he had with him was a very basic, point and shoot camera. He stopped when he reached the end of the roll, and we sat down by the river.

He told me that he thought I was honest; that I wasn’t afraid to speak about my relationships and my feelings. It was important in a friendship to be able to do this properly, not hidden behind a bravado that often concealed more than it revealed. As the river rolled by in front of us and the trees cast shadows across the lawn between where we sat and the Abbey behind us, he told me that he was sure he was going to enjoy our conversations. Come on, he said, pulling himself to his feet. He patted me on the shoulder. It was time to celebrate. It was his way of telling me that I’d got the room.

III.

Last night, after the ceremony, I walked back to my hotel with Pascal’s award in my hand. I walked because I was scared that if I sat down on a night bus I would fall asleep, drained as I was. I’d left the apartment early in the morning and arrived in London just two hours before the event was due to start, and all the way, through Germany and Belgium, France and under the channel, I’d been listening to Pascal’s voice. And as I stepped down from the train under the vaulting roof of St Pancras station to change to the underground, and when I returned to the surface to find a sandwich place to grab a bite to eat before checking into my hotel, he was still there, talking in my ear. The sound of his voice took me away from my immediate surroundings, from the train carriage or the seat at the sandwich shop window to wherever it was he happened to be talking about. It was only later, after I’d left the basement function room, with his award in my hand, that it finally felt like I’d arrived in London. And at that point, there was only another thirteen hours or so before I was due to leave again.

At my hotel I used a four-digit code to get in through the front door and took the lift to the third floor. My room was small, a narrow walkway with a door off to a tiny bathroom, a single bed and a thin desk that was only slightly wider than a sideboard. On it sat a travel kettle and a single mug. One sachet of instant coffee, one thin stick of sugar, and one tea bag. A television had been bolted to the wall in a way that the only way to see it properly would be to perch on the window ledge. None of this mattered to me. It was just a room. A place to sleep.

Still, having put Pascal’s award down on the desk, I stepped back in order to take a photograph of this room with my phone. It was part of the process, to document the trip, but it was also a habit that had started since I began working on this project a few months before. I was looking forward to hearing what he thought. He would have opinions on this room that he would want to share, and I knew he would like to see it. Hotel rooms are his kind of place.

I lifted my bag up onto the bed. Unzipping it, I pulled out a cardboard folder that was resting on top of my change of clothes. The folder was full of photographs, printed in A5. I took them out and began to flick through. I was searching for hotel rooms, for places that reminded me of the one that I now found myself in.

I don’t know why. I was dead tired and moving on autopilot. Maybe it was so I could refer to it in any message I sent with my own photograph to Pascal; to offer up a hint of a place it might have reminded him of, a place from his own collection of photographs and memories. Another hotel room in another land could substitute for this corner room in a scruffy London hotel. The last room in the corridor, next to the lift, where the streetlight shone in through the blackout curtain I hadn’t properly closed, and where I would fall asleep to the sound of taxis drifting through the puddles that had gathered by the side of the road beneath the window. Perhaps he would see my photograph, and be taken away from the island for a moment, to another city, where the taxis drifting through the puddles sounded similar, but not the same, as the ones I could hear in London.

In the pub on the Euston Road, waiting for the train, I sip my pint and for the first time today, pull the headphones out from my pocket. The sound of the pub retreats as Pascal’s familiar voice fills my ears.

*****

‘There is a part of me, Ben,’ Pascal says, ‘that wishes I was born at a different time. Do you have this feeling too? I don’t think this is an unfamiliar wish. I think many of us think this at some point or other in our lives. We’d like to have been there on the barricades in 1968. Or at Woodstock. Or the very first Glastonbury. We’d like to have seen Pele playing in his prime or roamed the streets of Berlin with Christopher Isherwood. For me, I always wish I had lived at a time when it was possible, for some people in this world at least, to live out their days in hotel rooms.

I’m not talking about some kind of skid row flophouse where the reception desk is behind bulletproof glass and the dossers and drifters are collapsed into old sofas in the lobby. I mean respectable hotels, where you could live and be looked after, and spend your time worrying about your work or your love life, and not about laundry or cooking or paying the electricity bill. There was a time, when I was younger, maybe at university but in any event just before we met, when I thought it still might be possible. There were places where people still did it. You’ve heard about the famous one in New York? Everyone knows about that one. But I was sure there must be others too. In Mexico City or Bangkok. In Prague, because it was still cheap back then. Or in Budapest, where it was cheaper still.

I had this notion, based on reading too many books, wanting to live in the world of those books rather than the one we had, and it was a foolish notion I think, but what I wanted was to be with all the freaks and weirdos, to be part of that community who have opted out of normal society and are making their way through life on their talent and genius. You remember those stories we wrote? Sitting up in my room with a typewriter and a bottle of Jack Daniels. Oh God, I’m embarrassed to think about it even now. Embarrassed but maybe also a little curious to read them again. This is part of who we are and who I was, so it needs to be said. It needs to be included. I had this vision, around the time we first met, that it was going to be just me, my bag and my camera. It was all I would need to make my way, like a busker’s guitar.

When I’m not feeling too hard on my younger self, I recognise that part of me knew I was a fool even then. Just another of those earnest young literary men who have read too much Kerouac and Hesse, and not enough women. We thought we’d found a shortcut to authenticity. To an authentic life, whatever the hell that means. By the time we met I was already over the worst of it. There was the occasional relapse, with the typewriter and the bourbon, but if I remember rightly you did most of the writing anyway. I liked the words better when they were still in my head.

No, by then I’d worked out that my camera could be my busker’s guitar, but there was easier money to be made using it to record the achievements of others rather than for any great artistic vision of my own. I could capture the joy of victory, the anguish of defeat. The desperate dive for the line and the majestic swing of a bat. It could all be captured through my telephoto lens.

But as I went through this process, working out how to make it work for me, I never lost my love of hotel rooms. It never diminished over the years, even after thousands of assignments. The press trips and expeditions. If anything, the appeal grew stronger. Can you understand that? Most people can’t. They profess to like hotel rooms, especially ones which are nice or which are fancy. Somewhere to stay that gives them something to show off about when they get home. But I think most people are happy to leave eventually, however nice the hotel might be, however luxurious and privileged it makes them feel. They are happy to go home. I know it because they told me. My fellow photographers. The journalists and the producers. Other guests, who I met over a late drink at the bar. After a while they were all ready to leave. But not me. I didn’t feel it.’

*****

I finish my drink and hoist my bag onto my shoulder. I step out into the rain, pulling my hood up over my head, tucking Pascal’s award under my jacket, even though it is made of plastic. As I hurry down the street to the station, Pascal continues to talk.

*****

‘I think it is clearer to me now than it was back then,’ Pascal says. ‘Perhaps it is because I cannot see when I will stay in a hotel again. They have always spoken to me, and they speak to me still from a great distance. I think it’s the simple fact that from the moment they open their doors and welcome their very first guests, they are already in the process of becoming out of date. Out of time. It is impossible, unless a hotel is to renovate and redecorate on an almost permanent basis, to keep up with the times, with the dictates of fashion. In that sense, a hotel is a lot like a map. From the moment they are put out into the world, they are already out of time. Old-fashioned. Last season’s colours. Furniture from another decade. Prints on the wall from another century.

This is what I like. Especially this. The sense of being out of time. Or that time has stopped. You don’t really exist any more in your normal, everyday world. None of your routines matter. I always thought, checking into another hotel room, into another anonymous place where the normal strictures of my life no longer applied, that if time has stopped, well, in this place at least, that must make me immortal.

Can you hear that I am smiling, Ben? Should I resurrect my dream? Once I wondered if it was a viable plan for my retirement. That I could live out my days in a series of modest hotel rooms. It’s probably the only long-term plan I ever had. Please make sure this is in there. Desires unrealised are just as important as those that were fulfilled. Especially now.’

*****

The recording ends as I enter St Pancras station, heading to the Eurostar terminal entrance, below the platforms among the shops. A young woman sits at a piano with a supermarket bag at her feet and plays a tune, recognisable but unnameable to most who stop and listen. I am the same. It is one of those pieces of music that is often used in adverts or in a film score, the soundtrack to the final montage of a live television event. I have presumably heard it played by some of the world’s finest musicians and by buskers in the shopping precinct. And now by this young woman taking a break from her shopping.

She plays it well, with joy on her face as her fingers dance across the keyboard. When she finishes there is a smattering of polite applause as she vacates the stool, picks up her shopping bag, and melts into the crowd. The rest of us wait for a moment, to see if anyone will step forward to take her place. But no one does, and we begin to drift off, each returning to what had preoccupied us before she started to play.

I move quickly through the ticket check and passport controls, the security scan and the other elements that make this like no other train journey I’ve ever made. But however close this might feel to flying, there is a platform at the end of the rigmarole, and for the purpose of this trip, it had to be the train. At the cafe I pick up a coffee and then find a seat, pulling out my notepad and my phone, searching through the files, until I find the one that I’m looking for. It is linked to a photograph in my bag. An overnight train, somewhere in Asia.

*****

‘To my mind,’ Pascal says, ‘the train is the crowning achievement of human transportation. It is a collective solution to a particular problem, a means of getting us from A to B that is social, that brings people together. Why do you think we have novels set on trains, or films? People can meet in their compartment or the dining car. They can fall in love. Make friends. Smoke cigarettes together or plot the downfall of a government. They can decide, on a whim, to cut short their journey at the next station or extend it to the very end of the line in order to carry on a conversation they’ve already begun. We created this brilliant thing, this perfect thing, and then we nearly destroyed it. We spurned it for the car, for the individual freedom of the automobile. To my mind the train is a symbol of the best of what we can do. The car is symbolic of everything that has gone wrong in our society.’

*****

I wait out the pause, my pen poised. I can hear Pascal sigh.

*****

‘Don’t mind me,’ Pascal says. ‘I’m just not… There’s basically no cars on the island. Isn’t that great? No trains either, but still. Anyway, it’s about solidarity, I think. Solidarity, yes. That’s the best way to put it. It’s about solidarity, and that’s why we should take the train.’

*****

Beneath the huge, arching roof of St Pancras I walk along the platform until I find my carriage and climb aboard. Settling in to my seat, I pull out the folder of photographs and put it with my notepad on the little table in front of me. I’m one of the first onto the train, but as I settle into my work it fills up around me. A woman sits down next to me, with a German book in her hand and a set of headphones of her own. She makes no acknowledgement of my presence or our closeness. There does not seem to be much of Pascal’s sense of solidarity on offer, not on this particular train, not today.