Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

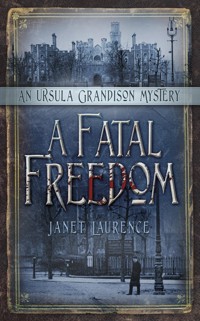

- Herausgeber: The Mystery Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

London 1903: American Ursula Grandison is once again involved with murder. As she struggles to make a living in a society where women have few rights and little freedom, she teams up with old friend and private investigator Thomas Jackman, who soon finds himself drawing on Ursula's investigative abilities as they battle to save an innocent woman from the noose. Set against a background of Edwardian constraints and the fight for women's suffrage, can Ursula and Jackman disentangle a bewildering web of motive and opportunity and prevent a subtle yet dangerous killer striking again?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 642

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to

Hannah Strong and in memeory of her parents,

Jeanie and Michael Sayers

Acknowledgements

The battle for women’s suffrage had been joined long before Emmeline Pankhurst raised its level to militancy. An excellent history of the whole campaign and the ideas behind it is The Ascent of Woman by Melanie Phillips, published by Little, Brown in 2003. Concerning poison, two books I found most helpful were Poison and Poisoning by Celia Kellett, published by Accent Press Ltd in 2009, and The Poisoner’s Handbook by Deborah Blum, published by Penguin Books in 2011. Helena Rubinstein’s autobiography, My Life for Beauty, published by The Bodley Head, in 1965, inspired my creation of Maison Rose. And Larry Lamb’s story for the BBC’s series Who Do You Think You Are produced the setting for the book’s first chapter.

I would like to thank Michael Thomas for reading and advising on the ms, my agent Jane Conway Gordon for her expert help and support, and the Mystery Press editors Matilda Richards and Emily Locke for their care and attention in the publication of this book. Finally many thanks to Shelley Bovey and Georgie Newbery, who have critiqued every stage of the writing of this book and without whom it would not have reached THE END. And to Peter Lovesey for his wonderful tag line. Any resemblance of the characters to actual persons, living or dead, can only be by coincidence, and all mistakes are mine.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Epilogue

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter One

1903

In the centre of London, just off the junction of busy Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street, was the jungle. A large carved screen carried images of wild animals: leaping lions, stalking ostriches, giraffes, monkeys, dancing bears, elephants. Ursula Grandison was captivated; surely no jungle could have contained all these animals? She remembered mountain lions back in the Sierra Nevada, where she’d lived in a mining camp. She’d heard one roar on a winter’s night, imagined it starving, seeking food, and had shivered in her makeshift bunk. Now she heard another lion’s roar, not coming through the silence of snow-covered mountains but rising over the crunch and clatter of traffic on a hot August afternoon in London.

Along one side of an opening in this show-stopping screen Ursula saw the words Crystal Palace Menagerie, and along the other, Patronised by Nobility and Gentry. A white-faced clown banged a drum in front, calling in the Londoners who thronged around the fair.

‘Something, ain’t it?’ said Thomas Jackman. He slipped a thumb inside an armhole of his waistcoat and sounded as proud of the scene as if he owned all of it himself. ‘That’s what’s known as “the flash”.’ He waved an arm at the screen. ‘In the trade they say “It ain’t the show that brings the dough, it’s the flash what brings the cash.” That’s what’s attracting all these folk.’

Ursula smiled at her stocky friend. When she had arrived in London, Jackman had been the only person she had contacted. A fresh start was what she needed, she told herself, after her tragic stay in the West Country. She had accepted his invitation for this afternoon with delight and met him at the fairground with real warmth.

Now, though, she saw the way his sharp eyes surveyed the crowds that excitedly pushed towards the opening, paying their entrance fee to view the wild beasts within.

‘Thomas Jackman, you haven’t asked me along here as a treat, you are on a job!’

He gave her a comradely grin. ‘I knew you were a fly one, Miss Grandison.’

She swallowed what she told herself was unreasonable disappointment. ‘Come on, now; didn’t we agree we’d drop the formalities, that you’d call me Ursula and I’d call you Thomas? After all, I’m a Yankee, not one of your high-falutin’ society women.’

‘American you are, and maybe not a society woman, but you got style, Miss Grand–, Ursula.’ He stood a little back from her and appraised her cream cambric shirt with its small red buttons and brown linen skirt trimmed with a band of darker brown just up from its hem.

‘Don’t try and soft talk me, Thomas. How dare you invite me here on my afternoon off on false pretences.’

‘False pretences?’

‘You send me a note suggesting I might like to visit what you call “an amazing menagerie”. You do not tell me the famous detective is on a job and needs a respectable companion for cover.’

He looked injured, ‘A suspicious mind, that’s what you got, Miss Ursula Grandison.’ Then he grinned at her again, ‘Didn’t I say you were a fly one? I should have known I couldn’t fool you for more than a minute. How did you catch on so quick?’

Disappointment over, she felt an odd satisfaction that she had seen through his little ploy. When they had first met, it had taken her some time to feel comfortable with this sharp-minded ex-policeman. But he’d earned her respect and for a very short time they had formed something approaching a detection partnership. However, she had no wish to continue the professional association.

‘You should have paid more attention to your female companion and less to searching out your mark. Isn’t that what you call a person you are trying to follow?’

‘That’s what a conman calls his potential victim.’

‘Not so different, I think.’

He gave a quick sigh and slipped his hand beneath her elbow. ‘Miss Grandison, Ursula, shall we proceed to view the menagerie?’ he said with exaggerated courtesy.

‘By all means, Mr Jackman, I shall be delighted. And at least I can assume that the entrance charge will be covered by your expenses.’

As she and Jackman moved towards the gap in the beautifully decorated screen, Ursula could not help looking around to try and identify who it was that the detective was interested in.

It was a varied crowd, all intent on seeing the wild beasts presented for their entertainment. It was too early in the afternoon for tradesmen and other workers; these were mainly wives and mothers with children. Like herself, they were dressed respectably but not in the height of fashion and from the middle to lower classes rather than the cream of society. Here and there were men as well, some accompanying women, others who looked as though they were idling away the afternoon. Ursula made sure her purse was securely fastened to her belt.

Then she felt Jackman’s hold on her elbow tighten. She followed his gaze. A woman and a man were entering the menagerie ahead of them. They seemed rather more stylish than the other sightseers. What, she wondered, was her companion’s interest in them?

Thomas Jackman had once been a member of the elite detective division of the Metropolitan Police Force; now he acted in a private capacity, which could mean anything from finding a long-lost relative, through dealing with stolen goods by owners who did not want to involve the authorities, to solving a mysterious death, which had been his commission when they first met. From what Jackman had told her, however, Ursula gained the impression he was most often called upon to obtain evidence of an adulterous relationship.

Once through the entrance, they found themselves in a huge tent supported by poles down its centre. The bright sunshine penetrated the canvas and clearly lit a variety of cages set around three sides. Lazy growls and grunts from bored animals mixed with excited comments from the visitors. Ursula’s nose twitched at the aroma of feral beasts, stained sawdust and the more familiar scent of human bodies overdressed on a hot day. By the sounds emanating from where the crowd was thickest, the most popular exhibits were lions.

Jackman steered Ursula towards a less populated part of the tent. A young woman, a dark-haired girl wearing a floppy cream beret over a long plait, studied a somnolent hyena. Her burnt-orange linen jacket and skirt was creased in the manner of that material, giving the impression of someone who cared little about her appearance. Further along the cage stood the couple the detective seemed to be interested in.

The woman looked to be in her late twenties and was stylishly dressed in a well-cut pale green suit trimmed with lace, her blonde hair carefully arranged beneath a graceful hat of fine straw trimmed with green flowers. Her hands, in cream kid gloves, clasped and unclasped themselves, the fingers writhing in a constant pattern of distress as the woman surveyed the trampled ground around them, her gaze moving everywhere except up at the man. He seemed to be pleading with her.

He was tall, with a shock of dark red hair almost hidden by a large hat with a floppy brim. Ursula recognised the look, she had seen it in New York; he was a Bohemian, an artist perhaps. A loosely tailored jacket in brown and beige checks and rumpled light beige trousers reinforced this impression. She could only see a bit of his profile, a straight nose and well-shaped chin, but his shoulders looked broad as he leaned slightly forward, as though imploring the woman to look at him, to listen to his words.

Jackman had positioned Ursula and himself before a wide gap in the three-sided arrangement of cages. Blank canvas hung over what could perhaps be an exit. Beside it was a low table covered with a cloth that reached to the ground. The cage they stood beside contained a couple of stately ostriches, their extravagantly feathered behinds looking dusty and bedraggled. Curiously small heads, held proudly above long necks, bore pop eyes that surveyed the scene with disinterest, then they bent to the floor and pecked at the straw in a desultory way.

Ursula, though, was far more interested in the little scene being played out by the pair near the hyena. The man reached forward to take the woman’s restless hands. After the shortest of struggles, she allowed him to hold them, lying limply in his, his solid thumbs caressing their backs. All at once, the girl studying the somnolent animal glanced sharply in her and Jackman’s direction and Ursula transferred her attention to the birds.

Where, she wondered idly, did ostriches come from? Africa? She turned to ask Jackman, but he’d moved to the table. From beneath its cloth, he fished out a Box Brownie camera. None of the happy crowds in the tent noticed, they all had their backs to him and were far too interested in the wild beasts.

He seemed to be preparing to take a photograph of the couple. Ursula looked back at them, wondering if there was enough light for a successful photograph; the sunlight was bright but filtered through canvas.

The woman at last turned her gaze up to the man and Ursula was struck by the beauty of her eyes. They were deep violet and had a rare radiance. She said something; her whole face lit up with joy and her hands moved to clasp the man’s tightly.

Jackman moved stealthily to his right, trying to position the camera so he could achieve the shot he needed. Before he was ready, though, the girl with the plait abandoned the hyena, raced towards the detective and barged into him. He dropped the camera. The girl somehow scrambled up on to the table, put her fingers in her mouth and produced a stunningly loud whistle.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ she shouted. ‘Your attention, please!’ People turned to stare. ‘Look at these poor animals, living their lives in cages, don’t you long to free them? Such a noble word, freedom. But it isn’t only animals who need it.’

Ursula could not help admiring the spirit of the girl. The burnt orange outfit commanded attention, tendrils of dark hair beneath the beret had escaped the plait and softened her appearance. She had a full mouth, high cheekbones and fiery eyes that were ablaze with conviction.

People started moving towards her. Their mood hovered between interest and condemnation. ‘Well, I never!’ ‘Extraordinary!’ ‘Who does she think she is?’ and ‘Is this part of the entertainment?’

Thomas Jackman was cursing. He had no chance now of catching his subjects on film. Indeed, they seemed to have disappeared from the menagerie.

‘Freedom, ladies and gentlemen,’ the girl continued, her voice gaining intensity. ‘Freedom for us women – that is what we need. Join me now. Call Votes for Women!’

She was shouted down. ‘Disgraceful!’, ‘Shouldn’t be allowed’ and ‘Come away, dear’ could be heard on all sides.

Two burly men in well-worn suits appeared, obviously part of the menagerie, and headed for the table.

Ursula hated the idea of this spirited girl being apprehended. No point in trying to stop the men. What she needed was a way of shouting ‘fire’ without actually using a torch. Looking around, she found her gaze fixed on the lock of the ostrich cage. A padlock that should have been fastened hung open in the door’s metal loops. With her back to the bars, working blind, Ursula dislodged and dropped the padlock on the ground, then gently opened the door. Making a cheeping sound such as might attract chickens, she moved towards where the girl was now struggling in the grip of the two men.

It took no more than a few moments before a scream arose above the tent’s disjointed noise. ‘Those birds – they’re out!’

Ursula looked behind her. The ostriches were now stalking across the floor of the tent, their curious heads turning this way and that, the feathered behinds moving with the grace of a music hall dancer, their long, long legs taking them towards some parakeets. A young girl held out a hand as though she wanted to stroke one of them.

‘Get away from those birds, they’re vicious,’ called someone.

People moved hurriedly out of their way.

The two burly men abandoned the girl and hustled after the birds. Jackman tried to catch her but, moving with the speed and slipperiness of an eel, she eluded him, as well as some half-hearted attempts by others to detain her, and ran out of the main entrance. Jackman looked frustrated and furious.

‘What happened?’ asked Ursula.

‘Damnation knows! Begging your pardon, Miss Grandison. But that’s the very end of enough.’ Holding his camera, Jackman looked around the tent hopelessly. ‘They’ve gone. She was in cahoots with them, no doubt about that.’

Down at the other end of the tent the ostriches had been rounded up. The sightseers drifted back to look at the lions, the bears and the monkeys, all interest lost in the girl and her message, if, indeed, it had been a message.

‘But who were that couple? Why were you trying to photograph them? And how did you manage to hide your camera underneath that table?’

A man hurried up. Surely, thought Ursula, he had to be the proprietor of the menagerie. His costume was magnificent, Mexican bandit crossed with Spanish grandee; black hair was slicked down, thin moustache twirled up either side of his face, dark eyes flashing with anger. ‘Tom,’ he boomed. ‘You swore to me there would be no disruption; instead you cause uproar. The animals will take hours of calming.’

Ursula looked around. The occupants of the cages hadn’t seemed to pay much attention to any of the disruption, but perhaps the smaller ones did seem a little more lively than before. Certainly the hyena seemed to have woken up. At that moment two lions let off mighty roars; those standing in front of their cages fell back.

‘You see? Now I shall have to delay my show. I’m not putting my head into one of their mouths when they’re in that state.’

Jackman placed a hand on the man’s arm. ‘Pa, I apologise. I had no idea that girl would pull such a stunt. Don’t know who she is, where she came from. Did someone catch her?’

The splendid showman shook his head. ‘Gone – the men were too busy catching the birds, no one was on the door. And that’s another thing, how in heaven’s name did that cage get opened?’ He strode over to where the ostriches were being persuaded to re-enter their home, picked up the open padlock and waved it at the assistants. ‘When I find who was responsible for this, he will wish he’d never been born.’

‘Warn’t us,’ both assistants said. ‘Dunno how those varmints could’ve opened the door,’ said one.

‘Been some little kid, I bet,’ said the other. ‘Thought it was fun to have us chase them all round the place.’

‘I’ll have ’is guts for garters, whoever it was.’ Pa inserted the padlock into its loops. ‘Wicked bite those birds got; ostriches can kill. Bert, find the key and make sure the cage is properly locked this time.’

Ursula could not help feeling guilty. The padlock had not been her fault, but the birds could not have opened the door themselves. If she had known ostriches could be so dangerous, she wouldn’t have encouraged them. But to confess would cause even more trouble for Jackman.

‘Let’s get out of here,’ the investigator said. ‘I’m sorry about the fuss, Pa. There’s some money for your men, thanks for your help.’

* * *

Some fifteen minutes later Ursula and Jackman entered Regent’s Park.

‘Take a pew,’ said Jackman, waving at a bench.

Ursula was happy to accept the invitation. ‘Now,’ she said, ‘I think it’s time you told me what all that was about.’

Jackman set down his Box Brownie, wiped his brow with a cotton handkerchief and slumped hopelessly down beside her. ‘I don’t often fail but I’m out to the wide here. If I’m not careful, Peters is going to call me a right Bengal Lancer.’

‘Bengal Lancer?’

He straightened himself with a curt laugh. ‘It’s rhyming slang: a Bengal Lancer, a chancer. Forgot for a moment you’re a Yankee.’

‘Ah,’ said Ursula. ‘Lancer, Chancer; that’s neat.’

‘Neat? What’s tidy about it?’

Ursula laughed. ‘Didn’t someone say the English and Americans are divided by a common language? It’s a bit of slang. To us “neat” can mean that something is fit for its purpose.’

‘Ah,’ said Jackman. He sat silent for a moment and Ursula let him gather his thoughts while she admired the swathes of green grass and graceful trees stretching up to a magnificent terrace of stuccoed houses. They had some of the grandeur of Mountstanton, the house she had stayed in at the start of her visit to England. She didn’t want to think about what had happened there, so she prompted Jackman, who finally took a deep breath and launched into an account of his current assignment.

‘I was approached by Mr Joshua Peters of Montagu Place, Marylebone. Mr Peters is worried that Mrs Peters …’

‘His wife?’

‘Who else?’

‘His mother? No, I’m sorry, Thomas, of course it is his wife.’

‘He was worried his wife, Mrs Peters, is, as he put it to me, “straying from hearth and home”. He commissioned me to follow her for a spell to see if she was meeting up with some fellow.’

‘And it was Mrs Peters who was at the menagerie today? And the man with her was, I take it, not Mr Peters?’

‘You have it. She’s been meeting him regularly, putting on a show, making it seem that they have run into each other accidentally.’

‘An act just in case anyone who knew her caught sight of them?’

‘You got it. And she’s good at it; could get a part on the boards I reckon. Now, I managed to chat up Mrs Peters’ maid. Nice little thing, innocent as a newborn kitten. Told me how unhappy her mistress was with the master …’

‘My, you did chat her up well.’

‘It’s my manner,’ said Jackman smugly. ‘Charm the birds off the trees, I do.’

‘One moment she’s a kitten, the next a bird,’ said Ursula, straight-faced. ‘What is the name of this dear little girl?’

‘Millie. And Millie tells me how her mistress is to visit the menagerie today. Says how fine it’s supposed to be. I reckoned she was angling for an invitation from me for her afternoon off. I reported the matter to Mr Peters, without disclosing my sources …’

‘I’m glad you didn’t betray Millie’s indiscretions.’

‘Without disclosing my sources, as I said, and asked Mr Peters if he didn’t want to go along to confront them.’

‘In public?’

‘That’s exactly what he said to me. And he told me how tricksy Mrs Peters could be. She looks like an angel, he said, but he swears no schoolboy can lie as she can. Which is why he wanted a sworn statement of the different occasions I’d seen her with this man. And then he asked if I couldn’t arrange for a photograph to be taken of them at the menagerie. Said she would not be able to explain that away. I said he didn’t know what he was asking. Could hardly get them to pose for me, could I? And I couldn’t set up flash photography. I told him I’d have a go with a Brownie, but I doubted there’d be enough light to develop a recognisable image.’

‘Yet another one of your talents, photography?’

‘Always been interested. And it comes in useful from time to time.’ He unslung the Brownie from his shoulders. ‘Such a clever little box this. Got a rotary shutter, takes snapshots and timed exposures as well. Three stops and two finders.’ He turned the camera around to show Ursula. ‘This one’s for upright exposures, like portraits, and this one’s for horizontal, landscapes they call them. All very straightforward.’

‘I’ve seen advertisements for them,’ Ursula said. ‘They seem aimed at the young.’

‘They’re much more than a toy,’ said Jackman. ‘Anyway, Mr Peters said he would make a snapshot worth my while.’

‘But what about the girl? Who was she?’

Jackman groaned. ‘I reckon she’s Mrs Peters’ sister. Millie told me about her, said they were very close. ‘I’d fixed it with Pa earlier, Charlie Maddocks I should say, but he’s always known as Pa, and his wife’s Ma. We go back a long way; I’ve run into Charlie and his menagerie – and the circus that’s part of the set-up – all over the country. Anyway, he’d agreed I could leave the camera in the tent. I know how visitors spend their time looking at the beasts. And I reckoned that Mrs Peters and her fancy man would be a little apart from the main crowd, seeking a bit of privacy, know what I mean?’ He looked at Ursula.

‘Indeed.’

‘When I saw the two of them standing close together, so still, with him holding her hands, well, I thought it might work after all. Then that wretched girl pulls her stunt.’

‘Is there any chance Mrs Peters could have suspected that she was being followed? Oh, I know you’re very skilled, and you’ve told me some of the tricks you use, moustaches, wigs, different hats and style of clothes, but Mr Peters’ comment about her being able to explain anything away suggests she is much sharper than she looks. So, she asks her sister to come along with her to meet this man. Do we know his name?’

‘Mr Daniel Rokeby.’

She wondered how he’d found this out. ‘She may well have thought putting someone on her track was the sort of dirty trick her husband was capable of. I think she put her sister completely in the picture. So while she speaks with Mr Rokeby, or allows him to speak to her,’ she added, remembering how silently the woman had listened to the man, ‘the girl pretends to be looking at the hyena but is actually keeping an eye out for someone who could have followed them.’

‘Watching me?’

‘If Mrs Peters has noticed you, she will have described you.’ She surveyed Jackman. ‘About five foot nine inches, well built, looks around forty years old, has a fine head of light brown hair, sideburns, thick eyebrows that almost meet, brown eyes, a slightly beak-shaped nose, wide mouth.’

He looked astonished. ‘You reckon she could have clocked me that well?’

‘If she’s really cheating on her husband, and she’s as bright as he suggests, yes. And could you perhaps have underestimated her? How many times have you followed Mrs Peters?’

‘Six.’

‘And where have they met?’

‘The first time was this park, the second an art exhibition, then there was some sort of literary society meeting, I had a little difficulty getting into that, not being a member …’

‘I expect that’s where Mrs Peters noticed you. And once she had, she would have kept a very sharp eye out. Her description might not have been quite as detailed but enough for her friend or sister to know who to look out for.’

For the first time in their acquaintanceship, Thomas Jackman looked chastened.

‘That speech about freedom for the animals and the cry for Votes for Women was a marvellously judged piece of distraction.’

‘It’s a cry that’s becoming more and more familiar,’ said Jackman gloomily.

‘Votes for Women?’

He nodded. ‘Your sex has a lot to answer for.’

‘It’s a cry we are hearing in America as well. I think it’s only fair for women to get the vote. Why shouldn’t we have equality with men?’

Jackman hardly seemed to hear this. ‘Now I have to go to Mr Peters tomorrow and explain just how I have failed. No doubt Mrs Peters is currently back at Montagu Place sipping a glass of wine and making eyes at her husband.’

Ursula thought about the maid who had told Jackman that her mistress was unhappy and she remembered the radiant look that had come over the face of the woman with the wonderful eyes, as though she had at that very moment made a decision.

‘What is Joshua Peters like?’

‘Hard business man. Not the sort of man I like to cross.’

Could such a man make a good husband? ‘And would you say he loved his wife very much?’

Jackman gave her a sharp glance. ‘What you’re asking is, does he look on her as a prize he would hate to see given to someone else?’

Ursula nodded.

‘I’d say that would about sum him up.’ He sat fiddling with the chain of his watch. ‘I wish I knew how those wretched birds escaped.’

‘Yes, that was unexpected,’ said Ursula. ‘Do you think the girl opened the cage before she leaped on the table to give her speech?’ She felt even Mrs Peters could not have improved on the innocence of her look as she said this.

Jackman, though, took a deep breath. ‘You, it was you, Ursula Grandison. You couldn’t see a supporter of Votes for Women get her comeuppance, could you? Never mind about loyalty to me!’

‘Loyalty to you? How about you not telling me anything about why you had issued your invitation?’ Ursula rose. ‘Enlisting my help but keeping me in ignorance! Not to mention giving all your aid to a self-serving husband instead of helping an unhappy wife. And you wonder why women want the vote!’ She drew on her cotton gloves. ‘My boarding house will shortly be serving supper. No doubt cabbage will be a prominent dish but maybe we shall be fortunate enough to have brisket on the menu as well.’ She held out her hand. ‘Goodbye, Mr Jackman. It has been an interesting afternoon.’

She left him sitting there, staring after her in stunned silence.

Chapter Two

Ursula Grandison had arrived in London that July with a small amount of savings and no contacts.

It was her choice. After three months spent in a stately home as companion to a young American girl, she had been offered every help in establishing herself in the capital. Instead, bruised and disillusioned by the disastrous events at Mountstanton, she preferred to strike out on a new phase of her life relying on nothing but her own resourcefulness and a single reference.

Her train had brought her to Paddington Station. Consigning her case to the Left Luggage, Ursula had rapidly found any number of small hotels of reasonable cost and some that provided adequate cleanliness and comfort. She chose one, handed over her passport and sent for her luggage. At the local library she scanned the periodicals provided.

Soon she had a list of agencies that offered their services in finding staff for respectable households.

‘A lady’s companion, is that the position you are seeking?’ The interviewer was a brisk woman who looked to be in her late forties. Her solid body was encased in a well-cut but conservative dark grey shirt and skirt. The shirt sported a thin black tie. On the dust-free desk in front of her were neat piles of buff-coloured files and a glass vase with a single cream rose.

‘Now, Miss Grandison, perhaps you will be good enough to give me details of your experience.’ Mrs Bundle sat straight-backed, pencil poised, taking in her applicant’s appearance: the neatly swept-up chestnut hair underneath the black straw hat with its very small brim; the rather fine grey eyes; the black linen suit, freshly ironed that morning, that was no more than neat.

Ursula gave a carefully edited account of her suitability to offer companionship to a lady who might need someone to cope with correspondence, run errands, perhaps deal with servants and generally make her life easier.

‘You are American,’ Mrs Bundle stated looking at her notes. Both her tone and her expression said this was unfortunate. ‘You do not know London and have only been in this country a few months.’

‘But that time was spent in the highest society circles as companion to a young lady of great wealth,’ Ursula said steadily. ‘I am familiar with how social matters are handled in England. Reaching the end of my time there, rather than returning to the States, I have decided to remain in England. I am anxious to discover London.’

‘It is slightly surprising that the aristocratic family you have been residing with have not provided the sort of contacts that would yield suitable employment.’ Her tone said this circumstance was suspicious.

Ursula forced herself to forget exactly how her employment as companion to Belle Seldon had ended. ‘You will perhaps be aware of the family’s tragic circumstances. They, and I, are in mourning.’ With the smallest of gestures, Ursula indicated her outfit. ‘However, the Dowager Countess was kind enough to provide me with a reference.’

Mrs Bundle picked up the sheet of paper with its ornate crest and fierce black handwriting. ‘The Dowager appears to have been completely satisfied with both your skills and behaviour,’ she said slowly.

Ursula dipped her head in acknowledgement of the encomiums which had been provided. ‘I am a quick learner; I am used to dealing with difficult circumstances and to mixing with a wide variety of people.’ She smiled inwardly as she thought of her life amongst silver miners in the Sierra Nevada. ‘I am confident of being able to fulfil any tasks I would be set,’ she added persuasively.

‘Are you, indeed?’ Mrs Bundle regarded her closely. ‘It is no doubt your American background that allows you to sell yourself so strongly.’

Ursula said nothing.

‘It is in your favour that you do not seem to have one of those nasal and, frankly, ugly American accents,’ the interviewer added thoughtfully.

Again Ursula said nothing.

Mrs Bundle leafed through several files and Ursula felt a tiny seed of hope.

* * *

Three days later, the seed of hope had withered. Four appointments with elderly women who required a companion had led nowhere.

‘You seem a very nice person,’ one had said apologetically after a short interview. ‘I do not feel, though, that you will allow me to be comfortable in my ways.’ The lashes of the tired eyes had fluttered sadly. ‘Agnes was so quiet, she, well, she melted into the background. Just always there when I needed her.’ A handkerchief was produced. ‘A wasting disease has taken her from me.’

After all the interviews had been concluded, Ursula once again sat in Mrs Bundle’s office while the employment consultant went through the results.

‘I am afraid, Miss Grandison, you appear to prospective employers as too independent of mind.’ She picked up the last letter. ‘Is it that independence of mind which did not allow you to take up the offer of a position as companion to Lady Weston? She appears to think you could have been suitable.’

Ursula shifted a little uncomfortably in her chair. ‘When I asked if I would be permitted to practise on her piano, a fine Bechstein,’ she added. ‘Lady Weston said, quite coldly, that there was an upright in the servants’ hall that would be available for such spare time as I would have.’

Mrs Bundle removed her spectacles, placed them on the desk and sighed. ‘Miss Grandison, you do understand the nature of the position you wish to obtain?’

Ursula nodded. ‘I do, Madam. And I was conscious that Lady Weston and I would not do well together.’

Mrs Bundle replaced her spectacles, flipped through her manilla folders, then laid a hand on the pile. ‘I am afraid there is no other position for which I can arrange an interview,’ she said briskly. ‘However, I have your address and will let you know if a suitable vacancy becomes available.’

Ursula left the office with little hope that one would. Her visits to other employment agencies proved equally unproductive.

Tired of rejection, she sent a note to the one London contact she was willing to get in touch with and was cheered by the immediate response she received. Thomas Jackman, ex-policeman and now private investigator, visited her the next morning and Ursula was surprised to find how very welcome his appearance at her hotel was; she remembered how, working together as they had at Mounstanton, initial distrust had gradually been replaced by respect on either side.

‘Shall we go for a walk?’ he suggested, looking around the unattractive hotel hall.

‘It’s very clean,’ Ursula said apologetically. ‘I am afraid I cannot afford the charges of a fine hotel. And I have known much worse than this.’

It was a sunny day. Jackman walked her into Kensington Gardens and across a bridge over a stretch of water she was informed was the Serpentine. ‘A popular place for swimming; frequented, I believe, by the Bohemian set of Pimlico,’ Jackman said.

They passed two nurses pushing highly polished perambulators, chatting merrily while their charges in sweet little lace-edged bonnets waved rattles at each other.

‘Kensington Gardens is very popular with society nannies,’ commented Jackson. ‘You will always find them on parade here. Now, why don’t you tell me why you are in London and what your intentions are.’

Ursula was happy with the bluntness of his approach and the way his square, craggy face had listened intelligently, his bright eyes full of amusement at her description of the society ladies who had interviewed her.

‘My, Miss Grandison, they have had a narrow escape,’ he observed at one point. ‘You would have organised them into oblivion almost as soon as you commenced your employment. I am feeling quite sorry for the luckless lady you finally accept.’

She sighed. ‘I am afraid I am not having much success in that line.’ There was a little pause, then she added, ‘I have to hope that something will come along soon. But,’ she rallied, her tone bright, ‘I need to find a suitable boarding house. The charges at that hotel, mean though it is, are too much for me. Would you be able to help me find one?’

He gave her a wry smile.

She quickly put a hand on his arm. ‘Please do not think that is the only reason I contacted you. When we parted in Somerset, you were kind enough to say that if I did come to London, you would be happy to continue our acquaintance. I was hoping you might introduce me to some of London’s sights.’

‘I shall be delighted, Miss Grandison,’ he said, then produced a notebook and pencil and scribbled down several addresses. ‘The proprietors are all known to me personally and I have no hesitation in recommending them.’

They spent a little more time walking through the pleasant environs while Jackman entertained Ursula with an account of a recent case he’d been involved with, then he returned her to her hotel with a promise of future contact. ‘But let me know your new address,’ he said, tipping the curly brim of his bowler hat as he left.

The second of the recommended addresses was a terraced house just west of Victoria station. It only accepted female boarders. Mrs Maple, a bony woman with a severe face, showed Ursula a second-floor room. Reasonably sized, it contained a bed with a firm mattress, a comfortable armchair, a small table with a bentwood chair, a hanging rail shielded by a curtain, a chest of drawers and, behind a small screen, a washbasin. Mrs Maple’s stern expression lightened as Ursula expressed her delight at this feature.

‘Mr Maple insisted that every room be provided with running water,’ she said. ‘Poor man, he knew he was not long for this world and was determined that after his demise I should be provided with the means for a reasonable income.’

Ursula announced that she would be very happy to take the room and pay two weeks’ rent in advance. As she counted out the coins, she silently hoped that before it was due again, she had obtained employment.

She moved in the next day and posted a note to Jackman thanking him for his help and confirming her new address. Arriving back at Mrs Maple’s after another fruitless interview, Ursula was met by Meg, the lanky maid-of-all-work. ‘Oh, miss, Mr Jackman’s here. He’s with the mistress and she says you’re to go to her parlour.’

Mrs Maple was laughing as she handed the investigator a cup of tea in the room at the back of the house she reserved for her private use. ‘Ah, Miss Grandison, Mr Jackman has called to see you are settled. Mr Jackman is a good friend, I don’t know what Mr Maple would have done without him sorting out that crook of a builder he had the bad luck to employ. Sit down and have a cuppa, won’t you?’

Ursula was happy to oblige. Her feet were tired from another day of walking around London in her hopeless quest.

‘How pleasant to see you again, Mr Jackman,’ she said, sitting down. ‘Tell me more about the crooked builder.’

Soon Ursula was enjoying an account of various difficulties Mr and Mrs Maple had had setting up the boarding house. Under her severe demeanour, Mrs Maple gradually revealed humour and warmth and it was evident that she and Jackman had a companiable relationship.

‘And how has your day been, Miss Grandison?’ Mrs Maple asked after it had been explained how the crooked builder had been warned off by the investigator.

‘Without result, I am afraid,’ Ursula said brightly. ‘However, I have hopes for an interview that has been arranged for tomorrow.’

‘I wonder,’ said Mrs Maple slowly. ‘I ran into an old friend yesterday. We knew each other a long time ago. She moves in different circles these days. Mrs Bruton she is now, quite the lady.’ The dry way she said this told Ursula that Mrs Maple’s friend had patronised her. ‘She told me,’ Mrs Maple continued, ‘that Mr Bruton passed on two years ago and she is now out of mourning. She also mentioned that she has need of some sort of secretary. I didn’t give it attention at the time but with you looking for a position, Miss Grandison, I wonder … now, what did I do with the card she gave me?’ Mrs Maple started investigating her pockets. ‘Here it is!’ She handed over a piece of pasteboard.

The card was stylishly printed, the name ‘Mrs Edward Bruton’ printed in flowing italics, with an address in Wilton Crescent in smaller typeface on the bottom left-hand corner.

‘Now you write to her, Miss Grandison, and say you are available.’

‘Can’t do any harm,’ said Jackman. He rose. ‘Must be on my way, just dropped by to say hello to Mrs Maple and see you were settled, Miss Grandison.’

Ursula remembered how they had agreed down in Somerset that they would use each other’s first names. Somehow this didn’t seem the right time to remind him.

* * *

Two days later, Ursula met a fluttery woman in her forties who seemed happy to relate her circumstances. Mr Bruton had been considerably older than herself, there had been no offspring of the union, and the widow had been left well provided for. Now out of mourning, she was beginning to involve herself with various activities.

‘I wish to enlarge my circle of friends. Edward was a very private person, Miss Grandison.’ Mrs Bruton rearranged the wayward chiffon scarf that was draped over her pale pink crepe de chine blouse, prettily tucked and inserted with lace, the sleeves slightly puffed at the shoulder and anchored in lace-bedecked cuffs, each fastened with a row of tiny pearl buttons. A dark grey slubbed silk skirt, its cut pronouncing that it came from no ordinary dressmaker, managed to suggest that its wearer was slimmer than close inspection revealed.

The interview took place in the morning room of a fashionable home in Knightsbridge. Sun lit Mrs Bruton’s pale gold hair, artfully arranged in a sort of pillow with escaping tresses that suggested a mind free from too many formal restraints.

The face was softly plump with only a few lines around the eyes. The mouth had none of the stern qualities Ursula had discerned in those older ladies she had recently met who required companionship – or a genteel slave. The eyes were a gentle blue with heavy lids. Hanging from her neat ears were pearls whose sheen declared they were genuine, as was the long string around her neck. Her hands were soft; diamond rings flashed brilliantly on plump, white little fingers as their owner fiddled with her scarf.

‘As long as he had me to keep him company in the evenings, Edward was perfectly happy, he did not require social activity,’ Mrs Bruton continued, lightly touching a Lalique dish that sat on a small round table beside her chair. ‘Occasionally we would have one of his legal friends to a luncheon.’

‘Legal?’

‘Edward had been a solicitor. By the time we met, he was retired. He said I had been sent to enlighten the last years of his life. There was nothing he liked more than to play cards with me.’

It sounded a somewhat humdrum existence. Ursula wondered how captivating a companion Mr Bruton had been.

‘Did you travel, visit friends at weekends?’ she enquired.

‘Edward adored abroad.’ Mrs Bruton’s blue eyes suddenly sparkled as brightly as her diamonds. ‘He said the weather was so much better. We would stay in Nice in the spring, and we went to Berlin and Vienna; we loved Vienna almost as much as Nice. We would visit the opera, dine in restaurants and occasionally we would meet people. I always had to take new dresses and hats. He would buy me jewels, tell me how lovely I looked.’ She gave a musical little laugh. ‘I longed for the times we would travel, it was as though a door had been opened from a dull room on to one filled with light and gaiety.’ Mrs Bruton gazed out of the window that gave on to a small garden filled with soft greens and a variety of pink and white flowers. ‘Life has been very dull for me since his passing away.’ She reached a hand towards Ursula’s wrist in a confiding gesture.

‘While he was moving towards his end I hated to see him suffer. But, do you know, Miss Grandison, after he had gone, after the first relief that he was no longer in pain, I missed not only Edward but my efforts to turn his mind from his illness. I would read to him, relate little incidents I had noted in my afternoon walks to take the air. And I missed the activity of the sick room, the doctor’s calls, the nurses, the occasional visit from one of his legal friends. Was that dreadful of me?’

The soft blue eyes seemed anxious.

‘Mourning drains the spirit,’ Ursula said gently. ‘You must now welcome the opportunity to take up a social life again.’ Then she wondered at that ‘again’. It did not sound as though the woman had had much of a one before.

‘I want to involve myself in good causes,’ Mrs Bruton said earnestly. ‘There are so many who suffer in life and so many splendid women who organise relief for them. I wish to join their number. Also,’ she added quietly, ‘I am sure my dear Edward would not want me to bury myself away wearing widow’s weeds for all eternity. I have no children to occupy my thoughts or my days and I think I deserve some entertainment; do you not think so, Miss Grandison?’

Ursula hastily reassured her that that was so.

‘Now, let us turn our minds to why you have so kindly attended on me. With my social life expanding, I shall need someone to organise “At Home” cards, send out invitations, keep my diary, and advise on what should be served at such little thés and even soirées as I shall hold, shall I not? Also, I will need someone to assist at such events, for I am woefully unaccustomed to social matters in England. You, Miss Grandison, have such an air and with so splendid a reference from the Dowager Countess of Mountstanton, I can be perfectly at ease knowing that all is safe in your hands.’

It seemed that the position was being offered. Just as Ursula was about to say she would be happy to work for her, Mrs Bruton asked, ‘I do not think you mentioned how you knew I was in need of a social secretary?’

‘Mrs Maple, who I understand is a friend of yours, told me of your requirement.’

‘Mrs Maple?’ It seemed Mrs Bruton had difficulty recalling the name.

‘I understand she encountered you unexpectedly a week or so ago and that it was some time since you had last met.’

The blue eyes fixed a contemplative gaze on Ursula. Then light seemed to dawn. ‘Why, of course, Mrs Maple! Such a long time … and we had once been quite friendly. But, you know, the paths our lives follow can diverge. Poor Maisie, once she settled for Mr Maple, and I met my beloved Edward, we moved in totally different circles.’ Mrs Bruton looked around her immaculate room as though conscious its silk upholstered chairs, antique occasional tables, attractive water colours and porcelain ornaments were a world away from Mrs Maple’s functional boarding house.

‘If indeed it was Maisie Maple who sent you to me, I have a feeling I shall owe her a debt. Tell me, when could you start?’

* * *

‘Mrs Bruton seems so disingenuous, so unused to the ways of the world,’ Ursula said to Thomas Jackman a few weeks later. ‘Yet she is very shrewd. The position is only two and a half days a week and not live-in. However, the pay is not ungenerous and I may be able to find someone else who also requires a part-time secretary.’

‘It must be a relief to have some income,’ Jackman said. ‘Even if it is not as much as you need.’ It was one of Ursula’s half days and they were in a small eating place near Victoria station enjoying a pot of tea for two. ‘Tell me more about your employer, she sounds an interesting woman.’

‘I find her so. As I said, she is really much shrewder than she appears on the surface. Two women called on her the other day. She had a slight acquaintance with one but was meeting the other for the first time. They wanted to interest her in donating to some charity for orphan children. Mrs Bruton made them very welcome and wanted to know everything about the “poor little children”, as she continually referred to them: where the foundlings came from, where they lived, who cared for them, and particularly what sort of education they were being given. At the end of the tea, she said very sweetly that she would think carefully about all she had heard and would be in touch.’

‘Did she think they were trying to milk her?’

‘Afterwards she was quite angry and said fancy imagining she was unaware that the state provided education without charge for the poverty-stricken.’ Ursula gave a gurgle of laughter. ‘The women had been very stupid, for at one stage Mrs Bruton introduced the name of Froebel but they seemed unaware of who he was or his kindergarten principles.’

‘Did she not think they could be perhaps ignorant but still charitably inclined?’

Ursula shook her head. ‘She thought they were using every possible ground to convince her large sums of money were required to care for and educate the poor orphans.’

‘So, the poor little children will not be receiving any of the Bruton funds?’

‘Not through those agents.’ Ursula checked the pot and poured them both more tea. Soon, though, Jackman had to leave and she made her way back to Mrs Maple’s.

She was finding working for her new employer was both pleasurable and challenging. Mrs Bruton had a way of dealing with several subjects at the same time, interweaving the description of a new friend with plans for an entertainment and the necessity for enlarging her wardrobe of tea gowns. Ursula would find herself making confused notes that later had to be sorted out and sometimes required applying to Mrs Bruton for confirmation she had understood her wishes correctly.

‘Oh, Miss Grandison, what a silly woman you must think me. I meant that Mrs Trenchard was to attend luncheon with me on Thursday this week; I did tell you I met her through the church, did I not? Why, look at that dear little kitten in the garden, do chase it away, I saw it kill a bird the other day.’ After Ursula returned to the morning room, it was as if no interruption had taken place, ‘Then the tea party I wish to arrange, with Mrs Trenchard’s help, is to be the week after next. Now, where did I put the list of guests to be invited?’ Searching her desk, Mrs Bruton’s attention was caught by several samples of blue silk. ‘Which do you think, Miss Grandison, matches my eyes?’

The list found and Mrs Trenchard consulted, Ursula sent out the invitations. She memorised all the names and enjoyed trying to work out from the addresses and her scant knowledge of London where in the social hierarchy the various guests belonged, but she soon gave up.

Mrs Bruton’s cook was used to providing simple fare; apparently that was what Mr Bruton had preferred. For a formal tea more would be expected and Ursula spent much time consulting a well-worn edition of Mrs Beeton’s Household Management. Remembering the delicacies the chef at Mountstanton had produced for tea, Ursula had long discussions with Mrs Evercreech in the well-appointed kitchen, convincing her that miniature chocolate éclairs and tiny iced sponge squares were well within her capabilities and would be ideal beside the wafer-thin sandwiches with either cucumber or egg fillings and Battenberg cake she was used to producing.

‘A nice jam tart, that was what Mr Bruton liked,’ Mrs Evercreech said with a sigh as the book was closed. ‘Still, it will be nice to do something different for once, long as they turns out all right.’

‘You will do everything perfectly, Cook,’ Ursula said firmly.

On the day itself, her employer was, perhaps understandably, nervous. ‘I do so hope Lady Chilton will attend.’

‘She has accepted your invitation,’ said Ursula, consulting her list of guests to make sure her memory had not failed her.

‘And Mrs Bright, she is such a leader in political matters.’

‘Indeed,’ murmured Ursula, wondering how far her employer was determined to enter that arena.

Mrs Bruton adjusted the lace jabot of her powder-blue chiffon afternoon gown, then fussed with her enamel and sapphire bracelet. Ursula had managed to persuade her that single pearl earrings were more suitable for the afternoon than sapphires, but Mrs Bruton had insisted on the bracelet. ‘Edward so liked to see me wearing my precious things,’ she said sadly, laying the earrings back in her jewel case. Huckle, her maid, closed it with a snap that said she disapproved of anyone else advising her mistress on her appearance.

The delicate chimes of the little clock on the bedroom mantelshelf reminded the hostess she should be downstairs to receive the first of her guests.

Soon the drawing room was alive with fashionably dressed women managing to avoid accidental encounters with other hats and greeting acquaintances with every appearance of delight.

‘So pleased Mrs Bruton is taking up the cause, I am sure you were responsible, Mrs Waterside …’

‘Such a failure on the political side over the years, you have to agree, Mrs Parsons …’

‘Rachel Fentiman was so brave the other day …’

The voices came and went in Ursula’s ears as she supervised the maid serving the tea. Enid was every bit as nervous as her mistress and needed gentle encouragement.

‘Is they all here, Miss Grandison?’ Enid looked doubtfully at the last few cups on the side table.

‘I think so.’ Ursula tried to make a headcount of the room. Just as she decided one guest was still to arrive, the doorbell rang. Enid almost dropped a cup and saucer as she tried to decide which needed her attention more, the tea or the door.

Ursula rescued the china and said, ‘I will answer the bell, Enid; you continue serving.’

Standing on the doorstep was a girl with an alive face and though the plait had given way to a fall of dark hair beneath a cream beret, Ursula had no difficulty in recognising her.

‘Rachel Fentiman,’ said the girl. ‘Am I horribly late? My omnibus was so slow I think it would have been faster to walk.’

‘Please, come in, Miss Fentiman. Mrs Bruton will be so pleased to see you.’ Ursula opened the drawing room door for the girl who had made the freedom speech at the menagerie.

Chapter Three

Miss Fentiman gave Ursula an apologetic smile. ‘Afraid I’m a little late. I do hope Mrs Bruton will forgive me.’

She was wearing a cobalt-blue, short-sleeved shirt with a narrowly cut matching skirt; it was a severe design and yet it did nothing to dim the girl’s attractive aura of energy. Everything about her seemed fresh: the clear, peach warmth of skin, the shine of dark hair, the sparkle of vivid blue eyes.

Ursula led the way into the drawing room and announced Miss Fentiman’s name.

Mrs Bruton immediately came forward, as did Mrs Trenchard.

‘Rachel, my dear,’ said the woman. ‘Let me introduce you to our hostess. Mrs Bruton, this is my niece, Miss Fentiman.’

‘It is so kind of you to invite me,’ said the girl after apologising for her tardy arrival. ‘I do admire you for holding this event.’

Mrs Bruton purred. There was no actual sound, but Ursula could think of no other word to describe her employer’s satisfied expression or the way she laid a soft hand on the girl’s arm.

‘My dear Miss Fentiman. Your aunt, Mrs Trenchard, described you in such admirable detail that I have been longing to make your acquaintance. Now, how many of my honoured guests have you met before?’

A woman, well dressed but with hair scraped back unbecomingly beneath a plain straw hat and skin the colour and appearance of parchment, said, ‘Why, Miss Fentiman and I are old friends. She has been good enough to assist me in the East End hospital of which I am the chairman. Alas, she does not seem to have time for such activities these days. Other interests appear to have taken over.’

Such was the force of the woman’s antagonism, Ursula expected Miss Fentiman to be abashed. Instead she said, quite cheerfully, ‘How nice to see you Mrs Mudford. I hope St Christopher’s is faring well. Now that I am back from Manchester, I shall try and assist again, if that will suit.’

The slightest incline of Mrs Mudford’s skull-like head. ‘That pleases me, Miss Fentiman. Mrs Bruton, I trust I can interest you in joining our little committee? We do most valuable work.’

Before Mrs Bruton could respond, Mrs Trenchard said swiftly, ‘And I have been telling our hostess about the Society for Women’s Suffrage I am so closely involved with. Now that you are so sadly widowed, my dear Mrs Bruton, I am sure that you will support our Movement to achieve the vote for our sex.’

‘Mrs Trenchard,’ a small woman bustled into the little group, her generous curves beautifully contained in tightly tailored, bright pink linen. She said with determination, ‘It is votes for spinsters and widows we fight for, not all women.’

‘And,’ said Mrs Mudford, looking as though she chewed on a lemon, ‘you, Miss Fentiman, did the cause no favours by your behaviour the other day. Quite disgraceful. If your father were still alive, he would be ashamed of you.’

Miss Fentiman, her eyes sparkling, opened her mouth but, once again, Mrs Trenchard took the initiative. ‘I thought what Rachel did was splendid. That is what our Movement needs: action.’

Ursula, refilling cups of tea while Enid passed round the cucumber sandwiches and exquisite pastries Cook had produced, saw a rustle of interest pass through the others at the party. Up until that point, groups of two or three had enjoyed exchanging conversation with one another. Now it was as if the curtain had gone up on a stage.

Had all Mrs Bruton’s guests come on the recommendation of Mrs Trenchard? Ursula wondered, giving a recharged cup to a slight woman in a stylish grey silk outfit. She had not seemed on easy terms with any of them.

‘Mrs Mudford, will you not ask our hostess how she would feel if, having received the vote, she had it taken away from her on the occasion of a remarriage?’

The other woman bridled. ‘You go too far, Mrs Trenchard. Next you will be saying there are women who will vote differently from their husbands.’

‘Surely,’ Rachel Fentiman said in a most reasonable voice, ‘no woman of intelligence would allow herself to be instructed on how to place her vote?’ She turned to her hostess. ‘Mrs Bruton, I have only just met you and we have hardly exchanged more than half a dozen words, but you have the look of a woman of intelligence. Tell us, if you will, did you allow your husband to monitor and guide all your thoughts?’