Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

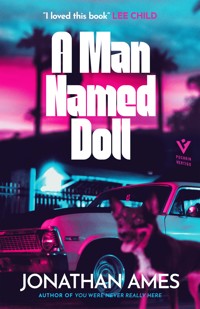

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

'Shot through with darkly comic flourishes. Motel, money, murder, madness: it has all you need to keep you happy' THE TIMES, THRILLER OF THE MONTH Meet Happy DollHap to his friends. He's a LA private detective living a quiet life along with his beloved half-Chihuahua half-Terrier, George. He's getting by just fineWhen he's not walking George or sipping tequila, Hap works nights at the Thai Miracle Spa, protecting the women who work there from clients who won't take "no" for an answer. Until he kills a manUsually Doll avoids trouble by following his two basic rules: bark loudly and act first. But after a deadly fight with a customer, even he finds himself wildly out of his depth... A Man Named Doll is both a hilarious introduction to an unforgettable character, and a high-speed joyride through the sensuous and violent streets of LA.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

PRAISE FOR A MAN NAMED DOLL

“I loved this book – it’s quirky, edgy, charming, funny and serious, all in one. Very highly recommended”

LEE CHILD

“If Elliott Gould’s Philip Marlowe landed in the middle of Uncut Gems, you’d have something like Jonathan Ames’ A Man Named Doll, which expertly mines the dark humour, mordant wit and dreamy fatalism of great LA noir. And at its centre is a detective with a battered heart and bruised conscience. I’d follow him, and his dog George, anywhere”

MEGAN ABBOTT, AUTHOR OF DARE ME

“A combination of dry wit, a satisfyingly high body count, and a nerve-tingling sense of pace make for a terrific seat-of-the-pants read”

SIMON BRETT, AUTHOR OF THE CHARLES PARIS MYSTERIES

“So fun and propulsive I didn’t just read it in one sitting, I read it in what felt like a single breath. Happy Doll is a tremendously likable main character, and the Los Angeles he inhabits is vibrantly alive in every detail”

LOU BERNEY, AUTHOR OF NOVEMBER ROAD

“Ames is a master of blending humor, pathos, and grit… A truly modern LA noir that still manages to feel timeless and steeped in the classics that came before”

ALEX SEGURA, AUTHOR OF BLACKOUT

“A smart, sharp, and stylish noir for the modern day. In his cinematic tour of Los Angeles that is both gritty and gorgeous, Ames has delivered a novel that is both current and timeless and has introduced a sleuth who fits all the old traditions while creating his own. Crime at its finest!”

IVY PACHODA, AUTHOR OF THESE WOMEN

iii

v

For Ray Pitt

(1930–2020)

CONTENTS

PART I

2

1.

SHELTON HAD ALWAYS been a hard man to kill.

But this time he looked nervous.

He came to my shabby little office on a Tuesday in early March, 2019. It had been a few weeks since I’d seen him last and he didn’t look good. But that wasn’t unusual. He never looked good. He was covered in liver spots like a paisley tie and was built like a bowling pin — round in the middle and meager up top. His head was small.

He was in the customer’s chair and I was behind my desk.

He was seventy-three, bald, and short, and getting shorter all the time.

I was fifty, Irish, and nuts, and getting nuttier all the time.

Outside there was a downpour. LA was crying and had been for weeks. The window behind my desk was being pelted; the noise was like a symphony gone mad.

It was rainy season. An old-fashioned one. An anomaly. Hadn’t rained this long in years, and LA had turned Irish green: the brown, scorched hills were soft with new grass, like chest hair on a burn victim. You could almost think that everything was going to be all right with the world. Almost. 4

“I’m in a bad way, Hank,” Shelton said. “That’s why I came to see you in person. Even in this weather.”

His tan raincoat was wet and splotched and looked like the greasy wax paper they use for deli meat. He fished his Pall Malls out of his right pocket and set one on fire. He knew I didn’t mind, and it didn’t matter anyway. Even when he wasn’t smoking, he smelled like he was. His open mouth was like an idling car.

“Why you in a bad way, Lou? What’s going on?” I pushed my ashtray, littered with the ends of joints, closer to his side of the desk.

“You know I lost the kidney, right?” he said.

“Yeah. Of course,” I said. “I visited you. Remember?” I took a joint out of my desk drawer, struck a match, and lit up. But I knew I wouldn’t get high. I’ve smoked too much over the years and I’m saturated with THC. So at this point, it’s just a placebo. A placebo that takes the edge off. Makes the nightmare something you don’t have to wake up from. You know it’s all a dream. Even if it’s a bad dream.

“I know. I know,” Lou said. “I’m just saying. You know I lost one, and now, well, the good kidney, which wasn’t that good, is going. And I’m looking at dialysis. And dialysis is a living death.”

He sucked on his cigarette. Lou Shelton had been smoking two packs a day since he was fifteen. He’d had open-heart surgery three times and had more stents than fingers. He’d survived mouth cancer and throat cancer and tongue cancer, and his voice was a toss-up between a rasp, a wheeze, and a death rattle.

I’d seen him once with his shirt off, and he had a fat scar, like an ugly red snake, down the middle of his chest. It was a 5zipper that kept getting opened, and from being in hospitals so much, he had a more or less permanent case of MRSA, which made him prone to boils on his ass that had to be lanced.

And he sucked on the Pall Mall.

Like I said, he was a hard man to kill.

“They say it’s definite? You got to do the dialysis? What is it, once a week?”

“Once a week? Are you crazy? You go every other day, sometimes every day. For hours on end. And you need help. A woman. A child. I don’t have any of that.”

Shelton’s wife, also a heavy smoker, had died of pneumonia five years before. She had gone fast. Her lungs were shot.

They’d had one kid, a daughter, but she wouldn’t see Shelton. After he lost the first kidney and wouldn’t quit smoking, she cut him out of her life. Said she couldn’t stand by anymore and watch him kill himself. Like mom.

Still, he sent her a nice check every month. He would never stop loving her, but I guess he loved his cigarettes more. He had a grandchild he’d never seen. And his daughter cashed the checks. Never said thank you. Why should she?

“Maybe dialysis isn’t that bad,” I said.

“No! It’s death. I’m never gonna do it.”

Part of me wanted to say, “Just give up already, Lou. You’re done. You’re dead. And you did it to yourself.”

But who was I to deprive him — in my mind — of one more cup of coffee, one more good feeling, one more bit of happiness?

So I pulled on my joint and said, “You could at least try it. Maybe it’s easier than you think. And what choice do you have?”

“No way. Remember MacKenzie from Homicide? He’s on it. 6Too much booze. Pickled himself. I went to see him. He’s bent over like a shrimp cocktail. Can’t lift his head. And nobody was tougher.”

“I should give him a call,” I said. But I probably wouldn’t. I always put those calls off, and then the person dies. Someday somebody won’t call me.

“He asked me to shoot him in the head,” Lou said. “He knows I still carry. He said, ‘Come on, Lou, you remember how I was. End this for me. Or just give me the piece and I’ll do it myself.’ I got out of there fast, and so now I’m telling everybody: I need a new kidney. I’m looking for volunteers. I’ll go off these —”

He stubbed out his cigarette and lit another. His troubled eyes were a watery, cataract blue — his nicest feature — and the smoke from the new cigarette plumed out of his nose, two wispy trails, not long for this world.

“What do the doctors at the VA say?” I asked. “Can you get a transplant?”

Shelton had been in Vietnam. Got a Purple Heart. But never talked about it. Like most people, he was a mix of things. Heroic and selfish. Insightful and blind. Sane and insane.

“I asked, but they won’t put me on the list,” he said. “I’m not a good candidate. It’d be a waste of a kidney … but not to me.”

“I’m sorry, Lou. This is rough. Real rough.”

“Anyway, even if I got on the list, by the time they called my number, I’d be dead. So I gotta buy one,” he said, and then added real fast, “I’ll give you fifty thousand, Hank. Maybe even seventy-five, maybe more — I’m working on an angle — and I’ll pay all your medical expenses. We just have to see if you’re the right blood type.” 7

Then he looked down, ashamed. I hadn’t caught his meaning when he said he was looking for volunteers. “Lou, jeez. Come on,” I pleaded.

“I’m serious,” he said, and he lifted his head and looked at me dead-on, not scared or ashamed anymore. He’d made his ask. “I know you could use the money. I’m O positive. What are you?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “But who’s gonna do the surgery? You can’t buy an organ and then find some doctor to put it in you.”

“No — I’d take you to the VA. They’ll check your blood and you say you’re doing it because you love me or because of God — there’s a whole process — but as long as nobody knows about the money, it’s totally legit. And they’d believe you, because we go way back. And because … you know.”

Now it was my turn to look down.

Lou Shelton had saved my life back in ’94. I was a rookie cop and he was a desk sergeant. But this one time, during a mini riot down in Inglewood, he was on the street with us. We needed extra bodies, and we were going around the alley side of a strip mall to get at some looters from behind, but they chose that moment to slip out the back, and there was a gunfight. Lou pushed me out of the way and took a bullet. Lost his spleen. The one thing not cut out of him because of the cigarettes.

But because of me.

Now he wanted one of my kidneys. Almost like a trade. I sucked on the joint. Could I do it? Should I do it? I didn’t know what to say. So he bailed me out. “Just think about it,” he said. “I know it’s asking a lot.”

“Okay, Lou, I will.” 8

“And it’s not all on you. Don’t worry. I’m asking everybody, and I’m looking into the black market. I met this kid. A computer whiz. A Pakistani at the motel” — Lou was the night man at the Mirage Suites, a transient motel on Ventura Boulevard in North Hollywood — “knows all about what they call the dark web. You heard of it?”

“Yeah, I’ve heard of it. But black market? Are you crazy?”

“What the fuck you want from me?” he said, angry all of a sudden. “I’m on death row! I gotta try everything. And if you can’t do it, you work that Asian spa. There’s gotta be one of them who’d sell me a kidney. You could ask around.”

“I can’t do that, Lou. You’re not thinking straight.”

“I’d be helping them! You can start a life with fifty grand. They could stop whoring. I’d be doing more for them than you do.”

I looked at Lou and put out my joint. A quiet came over us. The meanness and fire went slowly out of his eyes.

Then he said, “I’m sorry. That was a low blow. I’m not myself. But I’m desperate. I got maybe three months before this thing goes. I can feel it dying.” He nodded toward his abdomen, to the kidney inside him, a water bag gone bad.

“So just think about it,” he said, and stood up. “I had to ask.”

“All right, Lou,” I said.

He nodded and made for the door. On the other side of it was a metal plate that said: H. DOLL, INVESTIGATIONS & SECURITY. Most people call me Hank, but my real name is Happy. Happy Doll. My parents saddled me with that name. They didn’t think it was a joke. They’d been hoping for the best. Can’t say it worked out. Can’t say it didn’t.

At the door, Lou turned and looked at me. “I’m sorry about 9what I said. I know you take care of those girls the best you can.”

Then he straightened himself — there was still plenty of Marine and good cop left in Lou Shelton, and I caught a glimpse of it, his true self. He’d always been small and brave like a bullet, and he nodded at me and left.

I swiveled in my chair and stared out the window; it was streaked with tears. Rainy season.

2.

SHELTON LEFT AROUND five p.m. I finished my joint, locked my office, and headed out to the Dresden. The bar, not the city, and I ran up the street in the rain. The Dresden was only half a block away, and I wanted a drink. I wanted to mix some tequila with the marijuana and think about what Lou had asked of me.

The bar, which had just opened for the night, was empty, the way I like it, and the place hasn’t changed much since circa 1978: long oak bar, lots of shadow, no windows, red leather booths, and a battered piano, like an old horse that still wants to please, in the middle of the floor.

I took a seat at the end of the bar, and Monica Santos, my beautiful friend, drifted over, smiling. Monica’s got a long scar down the left side of her face, parts her silky brown hair down the middle, and is one of those people that has an actual twinkle in her green eyes. And I don’t know what that twinkle is, exactly, but there’s something in Monica’s eyes that is alive. She said: “What are you drinking, Happy?”

Monica knew my real name and liked it, and I didn’t protest. She had license to call me whatever she wanted. 11

“A child’s portion of Don Julio,” I said.

I always order alcohol that way — stole it from an old mentor, a cop long dead. But he used it for food because he had diverticulitis. I use it for alcohol because I’m Irish. But that’s not entirely true. I’m also half Jewish. On my mother’s side. I’m half Jew, half Mick, all ish. My father was a redhead and she was dark. I got his blue eyes and her black hair.

Monica gave me another smile, went off to get my drink, and as she reached for the bottle, I studied her profile. The one with the scar. Then I looked at the rest of her — she’s tiny but strong. She was wearing some kind of yellow halter frock, and her bare arms looked pretty. She had recently turned thirty-eight and had been bartending a long time.

She brought me my drink and rested her hand on mine.

A few years ago, when I was heartbroken, she had taken me into her bed. In the morning, I cried about the other woman and she never slept with me again. I had squandered her love. But not her friendship. She liked my dog and looked after him on occasion. And sometimes we met for coffee. But mostly we saw each other at the bar.

She squeezed my hand and said: “You doing okay?”

“Yeah. A friend wants a kidney, but I’m good.”

“What?”

“Only joking,” I said.

Just then a couple of regulars, old-timers, wet from the rain, sauntered in, and Monica went to them. They all love Monica, and she loves them back. She likes broken birds, and old men are her babies, her specialty. I hoped, sitting there, that I wasn’t in that category, but I may have been fooling myself.

So I took a sip of Mr. Don Julio and got off that depressing topic and moved on to another one: the pros and cons of the 12kidney question. I started with the cons: giving Lou a kidney, if I was the right blood type, was the definition of throwing good money after bad. How long would it last him? Two years? Less? His body was shot.

Another con was that I was a little squeamish. The idea of someone reaching into my body and taking something out made me feel funny.

I took another sip. And thought some more.

The cons ended there. At squeamish.

The pros?

Lou had saved my life. I wasn’t wearing my vest that day. That .45 would have ripped right through me. Lou was wearing his vest and the bullet caught the edge of it, which blunted some of the impact, so the bullet only nicked him but still took out his spleen. And he lived. I wouldn’t have made it without a vest — .45s punch holes in you that you don’t come back from.

Then I took another sip.

The tequila filled in the marijuana. Liquid in smoke. And I felt good. Generous. Magnanimous. Loving of my fellow man. Loving of Lou.

And I made my decision.

I’d get my blood tested and if I was O, he could have one of my kidneys, the right or left, whichever he wanted. And free of charge. No $50K.

And where was he going to get that kind of money anyway? He didn’t have any savings and his LAPD pension check went to his daughter every month. He must have been dreaming that he could come up with fifty thousand dollars.

I took out my phone to call him, but the battery was dead. I was always letting it run down. Because I hated the thing. Hated the phone. Hated being its slave and not its master. 13

I left Monica a twenty — I always overtip her; how can I not? — and started to head out. I was due at work at six, but I needed to stop at the house and walk the dog, and at the house, I could charge the phone. My car, a ’95 Caprice Classic, was too old for that kind of thing. Charging phones. It was from a simpler time.

As I got to the back door, Monica ran to the end of the bar and called out: “Have a good night, Happy. See you soon.”

“Yeah, see you soon,” I said. “Probably tomorrow.” And she laughed. I was in there most every day — because of her — usually around the opening bell, at five. Then she said, for no reason, kind of wistful, something she had never said before: “You know, I love you, Hap.”

I just looked at her, stunned, couldn’t say it back, though I wanted to, and so all I said, before stepping outside, was: “See you tomorrow.”

But I didn’t know then I wouldn’t be back in the Dresden for a long time. I didn’t know any of the bad things that were going to happen to me, and, worst of all, to Monica.

3.

I KEPT MY CAR in the lot behind the bar, and during the time it had taken me to drink my small dose of tequila, it had stopped raining and the sun, just before setting, had come out, and the light was magnificent. The world had turned purple.

I opened the windows as I drove and the air was fresh and sharp, and for a moment Los Angeles really was what the Spanish first called it: the Town of the Queen of Angels.

I headed north on Vermont and up ahead, on the mountain, the Griffith Observatory kept watch over the city, its wet dome like the head of an eagle.

I made a left onto Franklin, endured the traffic for a few lights, then made a right onto Canyon Drive in the direction of Bronson Canyon and the caves. I cut through the hills the back way and descended down to Beachwood Canyon and home. I live off of Beachwood Drive on a little dead-end street called Glen Alder. It’s at the base of the hill with the big wooden sign, the one that says HOLLYWOOD.

I parked in my detached garage, a white stucco box with terra-cotta shingles, opened the gate to the fence, and started 15my way up the forty-five stairs to my house, a white Spanish two-story bungalow built in 1923.

It has just four small rooms and a bathroom, but it was part of the original Hollywoodland development, and it rests high above the street, lodged into the side of a small hill. My front yard, feral and overgrown, is like a bit of sloping forest.

“Hello, everyone,” I said as I climbed, and I was speaking to all the trees and plants, and then in the dying light, I bent over some salvia and addressed them directly. “You’re so beautiful,” I said, and the thin purple tentacles swayed like underwater lilies.

I climbed some more stairs and touched one of my avocado trees — its trunk was strong and proud. Then, as I approached my house, which is shrouded by another avocado tree and a big elm, I said, “Hello, Frimma, darling,” which is what I call her. My house, like a ship, is female, and then I was through the door, and my dog, George, went nuts, jumping on me.

“Hello, George,” I said in English, and he said, “Hello, my great love,” in dog, which is spoken with the eyes. Then I plugged in my phone in the kitchen so I could call Lou after it charged.

In the meantime, George needed a walk and I grabbed his leash, and he started jumping even higher than he had in greeting. He’s half Chihuahua, half terrier of some kind, and quite springy. I’ve had him two years — he’s a rescue; someone left him chained to a fence — and he’s three or four years old, according to the vet. Unfortunately, I know nothing of his life before me, which I have to accept.

“George, sit!” I said. “Sit. Come on, sit!”

Finally, he calmed down enough for me to loop the leash around his neck and we went out the door. He was pulling 16hard down the stairs, but I didn’t care. He’d been cooped up all day and I wanted him to feel free.

Then we hit the street and I admired, as I often do, his small, muscular torso and how sleek and handsome he is. His legs are thin and elegant, as are his long-fingered paws, and his coloring — a tan head and body and a white neck — makes him look like he’s wearing a khaki suit and a white shirt, which is a good look for a gentleman like George in the semiarid clime of Los Angeles.

Trim and fit, he weighs about 22 pounds and has large mascara-rimmed eyes that break your heart and make you fall in love simultaneously.

Unlike most dog owners, I don’t project onto him that he’s my child, my son. Rather, it’s a more disturbed relationship than that. I think of him as my dear friend whom I happen to live with. In that way, we’re like two old-fashioned closeted bachelors who cohabitate and don’t think the rest of the world knows we’re lovers.

He does have his own bed, which I banish him to every now and then, but that’s very rare, and so we sleep together most every night of the year.

He starts off with his head resting on the pillow next to me, giving me moony eyes as I read — I always read before going to bed — and then when I’m tired, I put my book down and bury my face in his neck and inhale his earthy dog smell, which I love, and then I kiss his neck like he’s my wife before I turn off the light, and then he tries to put his tongue in my mouth, which I don’t allow, but I let him lick the corner of my eye to get some salty crust or something else tasty — it’s a whole ritual we have — and then when the lights go out, he burrows under the sheets and puts his warm body next to 17mine, and I’m ready to sing like Fred Astaire: “Heaven. I’m in heaven …”

So we walked down to Beachwood and then over to Glen Holly and back; he had one nicely formed bowel movement and at least two dozen marking urinations. Back inside, I filled his bowl with his food and made a quick plate for myself — a pickle, some crackers, some sauerkraut, and a can of mackerel whipped up with some Vegenaise.

Some intrepid ants were crawling around on the counter as I prepared this feast, but I didn’t have the heart to kill them. They were going about their business with such great purpose and industriousness that it seemed unfair to just come along and crush them. They had things to do! And I hate to kill anything.

So I took my plate into the small living room, where I have an old wooden table, and ate quickly. The pickle and the sauerkraut I thought of as my vegetables and my fiber, and the mackerel was my protein.

My eating habits are odd but healthy.

I was out of the house and headed down the stairs by 6:10, and George went out to his little wire enclosure, off the kitchen, to say goodbye. There’s a doggie door in the kitchen door, and the eight-foot enclosure beyond it — like a chicken coop — lets George get some fresh air when he wants to while keeping him protected from coyotes. He can also use it as a pissoir when necessary.

“Goodbye, George,” I said, and his eyes were sad, but I steeled myself and didn’t look back.

As I drove to work, I left Lou a message. Being even more old school than I am, he didn’t have a cell phone but a landline with an answering machine; he lived in a small unit of the 18Mirage, which came with a kitchenette and its own phone. He’d been living there for about ten years and the room was a perk of his job as the night man at the motel.

The answering machine made a beep — there was no outgoing message — and I said: “Lou, it’s Hank. Thought about what we talked about. I’d like to do it. Let’s go to the VA and find out if we match.”

Then I paused. I almost said “I love you,” but I didn’t. I just said, “So call me,” and hung up. I have no problem telling George or the plants or the trees in my yard or my house that I love them, but with people it doesn’t come so easy.

4.

MY NIGHT JOB was at the Thai Miracle Spa, on the second floor of a two-story strip mall at the corner of Argyle and Franklin, not far from my house.

I got there at 6:20, and Mrs. Pak, the owner, was working the desk. She lowered her reading glasses to give me a look but didn’t say anything. She was in her midsixties, but her hair was still lustrous and black, like oil. She was always very serious, but when she smiled, which was rare, she was radiant. That night, she was wearing a man’s white shirt, blue work pants, and simple black shoes. Her usual costume.

“Sorry I’m late,” I said.

“It’s okay. It’s quiet,” she said, then she pushed her reading glasses back up her nose and went back to her Korean-language newspaper.

I took my usual seat on the other side of the waiting room, across from the desk, and fished out the novel I was reading, which was in the front left pocket of my jacket. The book was The Great Santini, by Pat Conroy, and it was my second time reading it — I’m a sucker sometimes for sadistic-daddy books 20with a military angle — and I settled in and began the long wait for trouble, which might not come.

Mrs. Pak also owned the Laundromat and the nail salon on the ground floor, and I had been doing my laundry at her place for a long time, and about a year before, when I was waiting for my clothes to dry, she asked me if I could provide security at the spa in the evenings. She knew I was an ex-cop and ran my own business, and she thought it might be a good fit. I was broke and said yes, without really thinking it through, and so I became the muscle at a jerk-off farm, which wasn’t something to be proud of.

I did seven years in the Navy, ten years in the LAPD, and since 2004 I’d been on my own. Working the Thai Miracle Spa was not where I thought I’d be at fifty, but it’s where I ended up, working Monday through Saturday, six to midnight.

During the day at the spa, it was a mix of female and male clients, but the night trade was different: there were almost no women customers and a lot of the men had their drink on, which was why Mrs. Pak had wanted security. The strip mall is right near the entrance to the 101 and a lot of these drunks stopped off at the spa on their way home to the Valley.

Of course the girls weren’t supposed to have sex with the customers, but Mrs. Pak looked the other way at what she called “prostate release.” What she didn’t look the other way at was the extra cash it brought in, which she split 60/40 with the girls — 60 for her, 40 for the girls. Which was much better terms than most.

It was supposed to be a Thai spa, but all the girls were from China, and it was a crew of about twenty. They worked at all three locations — the Laundromat, the nail salon, and the Miracle — and it was like a big family. Mrs. Pak’s eighty-something 21mother cooked for everyone. In the back room of the salon, lunch was served at one, dinner at nine.

Mrs. Pak had one son — an ER doctor at Cedars-Sinai, whom she put through medical school at UCLA — but he never came around. Her ex-husband, a gambling addict and an old-fashioned morphine addict, lived in Reno, and so I was the only man on the premises, other than customers.

That night things were slow at first and I was tearing through the Conroy novel. In the Navy, they called me the Dictionary because I always had a book and liked to do crossword puzzles.

Then around eight things began to get busy, and whenever a man came in, I stood up and gave him a look while he conducted his business with Mrs. Pak.

Once the man paid, she’d lead him through the beaded curtain on the other side of the room and then down the hallway, which had eight little massage rooms, four on each side.

The look I gave the men wasn’t meant to frighten them off but to let them know that someone was there and that there were rules to follow. Loose rules. No intercourse, no oral sex, but hand jobs and a little fondling were okay. Also nursing.

Mrs. Pak had told me that a lot of the men just liked to suckle on the girls and would pay dearly for it, and I couldn’t say I didn’t understand. My mother died in childbirth and I was never breast-fed. Not even by a wet nurse. My analyst has implied — she doesn’t say things directly — that this is a big part of my problem in life and I don’t disagree.

It’s also something of an issue for me that my first breath was my mother’s last. It’s hard to forgive yourself for something like that, and it doesn’t make it easy for your father to forgive you, either, or even to love you. All of which has led to a strange 22life with George and four days a week on the couch. I think I’m the only ex-cop I know in Freudian analysis, but I could be wrong.

So I didn’t like the rules at the spa, didn’t like being complicit with what was going on, but being low on cash had made me stupid, and then I got caught up in thinking — more stupidity, vain stupidity — that the girls needed me.

At least three times a week, one of the drunken idiots who came for the prostate release — but then wanted something more — would get violent and rough, and I’d have to step in and do some arm-twisting, which does come natural to me. I’m six two, 190, all lean muscle from eating canned fish the way I do, and in the Navy I was a cop and in the cops I was a cop, so I know how to subdue people. There are two basic rules: bark loudly and act first.