6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

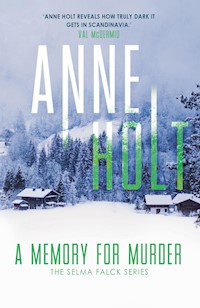

To Remember the truth, she'll have to forget the lies... When former high-powered lawyer turned PI Selma Falck is shot and her oldest friend, a junior MP, is killed in a sniper attack, everyone - including the police - assume that Selma was the prime target. But when two other people with connections to the MP are also found murdered, it becomes clear that there is a wider conspiracy at play. As Selma sets out to avenge her friend's death, and discover the truth behind the conspiracy, her own life is threatened once again. Only this time, the danger may be closer to home than she could possibly have realised...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR

‘Step aside, Stieg Larsson, Holt is the queen of Scandinavian crime thrillers’ Red

‘Holt writes with the command we have come to expect from the top Scandinavian writers’ The Times

‘If you haven’t heard of Anne Holt, you soon will’ Daily Mail

‘It’s easy to see why Anne Holt, the former Minister of Justice in Norway and currently its bestselling female crime writer, is rapturously received in the rest of Europe’ Guardian

‘Holt deftly marshals her perplexing narrative … clichés are resolutely seen off by the sheer energy and vitality of her writing’ Independent

‘Her peculiar blend of off-beat police procedural and social commentary makes her stories particularly Norwegian, yet also entertaining and enlightening … reads a bit like a mash-up of Stieg Larsson, Jeffery Deaver and Agatha Christie’ Daily Mirror

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Anne Holt, 2021

English translation copyright © Anne Bruce, 2021

Originally published in Norwegian as Mandela-effekten. Published byagreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by anymeans, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and theabove publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters andincidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination.Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events orlocalities, is entirely coincidental.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 868 7

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 856 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 858 8

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Also by Anne Holt

THE SELMA FALCK SERIES:

A Grave for Two

A Necessary Death

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:

Blind Goddess

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Death of the Demon

The Lion’s Mouth

Dead Joker

No Echo

Beyond the Truth

1222

Offline

In Dust and Ashes

THE VIK/STUBO SERIES:

Punishment

The Final Murder

Death in Oslo

Fear Not

What Dark Clouds Hide

To Jan Guillou, my friend, with thanks.

MAY 2010

Creation

Although she kept slurring her words and grinning, she was lovely. Elegant and charming, the way younger girls hardly ever were. A bit mumsy, really, but pretty brazen with it. Attractive. A full mouth with lips that looked real. Reddishblonde hair that definitely wasn’t. Well and truly plastered. She was standing there spewing into a rubbish bin by the fountains at Spikersuppa when he spotted her. He had lingered, watching her for a while, until she straightened her back, looked across at him and suddenly waved him over. He obeyed just as a rat scampered past her feet, the poor creature’s mouth stuffed with kebab or something. She was too far-gone to notice the beast. He felt sorry for her. He often felt sorry for people.

For himself too.

Things had progressed the way he wanted and she let him go home with her.

‘How old are you really?’ he asked for the third time.

‘Tick-tock, tick-tock.’

Maybe the woman was actually crying. Mostly she’d laughed, even though he’d had to hold on tight to stop her falling into the gap between platform and carriage at the National Theatre subway station. Her laughter was infectious, even in her drunken state. All the same, she didn’t seem particularly happy.

‘Tick-tock.’

Her apartment was drop-dead gorgeous. Not that he would exactly want to live in fucking Manglerud, at least not in a gigantic high-rise block. The place wasn’t especially spacious either, but the bird had seriously good taste, the sort you find in the pages of interior magazines: fairly dark colours, just enough books on the shelves and a far-too-discreet flatscreen TV, sort of thing. And those groups of empty vases and candles, arranged on wooden trays in an effort to look absolutely casual. Here and there, dotted all around, but not too many. The apartment was the perfect place to crash for the night, something he was totally dependent on at present. Any acquaintance or stranger, as long as it was clean enough and they were nice people, and he was saved until the next day.

‘Far too old,’ she complained. ‘The clock is ticking.’

He had brewed a huge pot of coffee and also poured a lot of water down the woman’s throat. He knew how she was feeling. It wasn’t often he drank enough to be totally sloshed, but when it happened, it was best to sleep it off. Hell on earth when you finally woke up, of course, but all the same.

‘Maybe you should sleep,’ he suggested as he got up from the settee.

‘No,’ she insisted, trying to pull him towards her. ‘You’re so sweet. So nice. I’m sure you’ll make a wonderful dad. Can’t we make a baby together?’

He laughed.

‘How many times do I have to tell you? I’m gay. G-A-Y. I don’t feel any desire for women … no offence …’

Taking a step back, he turned up his hands and showed his palms.

‘… and the last thing I want is children. I’m only twenty-one.’

‘It would be so easy,’ she said, struggling to sit more comfortably. ‘I’ve got all we need, and it’s the right time of the month, and …’

Her consonants must have been left at the bottom of a glass somewhere. Her hand dangled over the edge of the settee when she tried to stand up and she fell back again. No longer looking so good.

He guessed forty years old.

‘Thirty-eight,’ she said with a hiccup. ‘I’m thirty-eight, and it’s getting late.’

A snigger.

‘That rhymed! Come on, let’s make a baby.’

She shut her eyes. A few more minutes and she’d be fast asleep. He seized the chance to look around again. He spotted an iPad beside the pathetic flatscreen. She must have bought it in the US – it was only a month since Apple had launched the coolest gadget of the times. Bloody expensive. Bloody beautiful.

Sometimes he stole things.

Never much. Mostly food and drink. An odd time money, but only small amounts, and only in moments of desperate need. The tablet, with its bright red leather cover, looked really tempting.

‘A baby,’ she said in an unexpectedly firm tone of voice.

This time she managed to stand up. The grin was gone. She shook her head ever so slightly. Drained the half-full cup of lukewarm coffee. Put it down and stretched her back with her hands above her head, as if she had just woken up. He had hoped she would doze off on the settee, so he could lie down in the enticing bed that was most likely behind the nearby door. Now it would probably be the other way round. Fair enough. Beggars can’t be choosers, and the settee was absolutely fine.

She padded across the floor towards the open-plan kitchen, surprisingly steady on her feet now. Rattling in a drawer. Several drawers. He was staring at the iPad. He knew she also had an iPhone. In her handbag, the one hanging from a hook in the hallway, containing both her wallet and loads of makeup. It had toppled over between her feet on the subway and he’d had to help her gather everything up again.

‘Here,’ the woman said, raising an enormous syringe above her head.

Something for a horse. Or an elephant. It didn’t have a proper point, he could see that. No metal at all, in fact. Blunt and strange. It looked a bit like a toy hypodermic, the kind kept inside the dinky doctors’ medical bags that had a red cross on the front.

‘Do you have any food?’ he asked.

‘Yes, of course. Afterwards. First this.’

He wasn’t stupid. At junior high, he’d been top of the class. Smart and cocky, he’d heard his teachers say. Then his mother had died and there was no more school for him. Life went its merry way, in a sense. He stumbled along after it as best he could. Mostly living from hand to mouth. Sometimes like a prince. Most often not. He hadn’t had a fixed abode since his father had at long last lost patience with him and thrown him out the door.

When he was seventeen.

For four years he had lived off Social Security and the generosity of others. All the same, he wasn’t stupid, and when the woman waved the big plastic syringe yet again, he understood what she wanted.

‘Are you healthy?’ she asked.

‘Yes. But I can’t be bothered—’

‘No HIV infection?’

‘Course not,’ he answered, annoyed now. ‘I’m careful.’

‘Hereditary illnesses?’

Her consonants were back in place.

‘No,’ he replied. ‘At any rate, we’re not making a baby with that gadget there.’

She was right in front of him now. Her breath stank of vomit and coffee and red wine. Her tongue was a strange shade of pale blue. Her eyes even bluer.

‘Ten thousand kroner,’ she said flatly.

‘What?’

He took a pace back.

‘You’ll get ten thousand kroner. All you have to do is wank into a cup. In the bathroom or something. Give the cup to me and you’ll get ten thousand kroner. You look as if you need it.’

He hadn’t had ten thousand kroner in cash since his confirmation.

‘Thirty,’ he said in a flash. ‘I want thirty thousand.’

‘No,’ she said, crossing the room to the small unit where the iPad and flatscreen were.

From a little drawer she produced a wad of pale-brown notes, held together with something that looked like a hairband.

‘Ten thousand kroner,’ she insisted. ‘I don’t even know your name, so you’re taking no risks. No demands. Not for financial support or turning up at family birthdays. You give me what I want, you get the money in return and …’

She hiccupped and had to take a step to one side to retain her balance.

‘Christ,’ he said, ‘this is crazy. You can’t just make a kid like this. Kids shouldn’t …’

He ran his hand through his longish hair.

‘Why don’t you just go to Denmark or something? Or have a chat with a friend? Or find yourself a guy, for Christ’s sake, you’re—’

She was waving the banknotes.

‘You’re lovely,’ she said. ‘You’re Norwegian and blond and young. You’re kind. You helped me home. I’ve no idea how smart you are, but I’m sharp enough for two.’

He could strike her down. Take the money and run. She wasn’t just as out-of-it as she’d been when he’d found her a couple of hours ago, but it would be easy to overpower her. And she didn’t have a clue who he was.

‘Ten thousand kroner for a few seconds’ work,’ she said.

She was spot-on about that. It wouldn’t take long at all.

‘Plus the iPad,’ he said, pointing.

‘No. Ten thousand. Take it or leave it.’

‘But why me? Haven’t you got—’

‘You know nothing about me. I know nothing about you. Let’s keep it like that. Now I need an answer.’

He answered.

Ten minutes later, he stood alone in the hallway of the small apartment with an entire fortune in his pocket. The woman had taken the cup and syringe into her bedroom and asked him to leave. Without offering him any food as she had promised. It didn’t matter, now he could buy something. Her handbag still hung on the hook at the front door and he opened it carefully and drew out her wallet. She liked cash, this woman. Behind a photo of an Alsatian dog, there was a bundle of 200-kroner notes. Her credit card was firmly fixed inside the tight slot in the leather, but with a bit of jiggling, he managed to pull it out far enough to read her name.

If she had no idea who he was, at least he would know who he might be having a child with. On the other hand, getting pregnant at that age, after a more or less random attempt at artificial insemination while under the influence, would probably wind up being pretty difficult. After a moment’s hesitation, he pushed the card back into place without touching the cash. Then he dashed out to get some grub and somewhere else to sleep. Once he was some distance away from the apartment block, he made up his mind to pretend the whole absurd episode had never happened at all.

Curiously enough, though, he never forgot her name.

THURSDAY 5 SEPTEMBER 2019

The Assassination

When the shot hit Selma Falck, she was in fact only astonished.

It wasn’t especially painful. Just a jolt to her shoulder, at the very top of her left arm. She instinctively grabbed the entry wound, and noticed with increasing bafflement that blood was already seeping through her velvet jacket, staining it dark crimson.

A hell of a hullabaloo kicked off.

Tables toppled and people screamed. Cups, glasses and chairs flew in all directions. The customers in the crowded pavement restaurant threw themselves to the ground or sprang up to flee the scene. A pram parked at the far edge of the jumble of small tables tipped over and the mother’s shrieks cut through all the noise.

Only Selma Falck sat completely still. As the blood spread under her right hand, she grew gradually dizzier. Later she would insist that many seconds had passed, perhaps as much as a couple of minutes, before she realized Linda was dead.

The shot had struck Selma’s old friend from the national handball team in the head.

A sharp report had ripped through the autumn air. Not two, Selma firmly insisted. She remained seated, nausea denying her the ability to stand, while she struggled to shut out the cacophony of weeping and wailing and harsh warnings.

One single shot. Definitely not two. Linda had been sitting on her left. Vanja Vegge, Selma’s oldest friend, sat opposite them both. A stressed-out waiter had just thrown down a glass of water on the rickety little table. It was perched so far over, teetering on the edge, that it risked tipping over once the waiter turned his back to squeeze past the jam-packed tables. Linda Bruseth’s reflexes might not have been as good as they had been thirty years earlier, but she had avoided the accident at the final split second. Her hand was still clutching the glass and her head had dropped forward. It might even look as if she had dozed off in a drunken stupor. But all that had been on the table a few seconds earlier was the water, two cans of Pepsi Max and a cappuccino.

A fine-calibre firearm was what crossed Selma’s mind. The bullet had hit Linda at the back, on the side of her skull, where it had deposited mass and weight as it rotated inside her brain, changed angle and continued its journey through another, larger hole in Linda’s cranium before striking Selma’s arm. Dots danced in front of her eyes, black and green, but she managed to lift her injured arm sufficiently to see there was no exit wound.

‘The same bullet,’ she muttered. ‘And now it’s inside me.’

‘We have to leave!’ Vanja Vegge screamed hysterically from beneath the table.

‘She saved me,’ Selma said.

‘What? We have to go, Selma! There could be more shots!’

‘Linda saved me,’ Selma repeated. ‘But I don’t think she knew that.’

Then she got to her feet, swaying slightly. Taking a stronger grip of her left upper arm, she walked with surprisingly steady steps towards the wailing ambulance that was miraculously already approaching.

‘Anine must never learn of this,’ she mumbled all the way, over and over again. ‘My daughter simply mustn’t get to hear of this.’

As if that could possibly be avoided.

SATURDAY 7 SEPTEMBER

The Interview

Private investigator Selma Falck and Police Inspector Fredrik Smedstuen sat side by side in a cleaners’ cupboard at Ullevål Hospital. It was remarkably large. On the other hand, it smelled far from fresh. Damp patches formed rough patterns on the windowless exterior wall and putrid floor cloths were piled up in a corner.

‘Placing you in a four-person ward,’ the police officer mumbled, shaking his head. ‘In the richest country in the world. That’s how things have turned out.’

‘It’s fine,’ Selma snapped. ‘Anyway, I’ll soon be discharged. Just a flesh wound. And they did at least lend us this cupboard, didn’t they? For this little … chat of ours.’

She raised her eyes and let them run over the space. One wall was covered in enamelled metal shelves, crammed with so many poisonous cleaning agents that they could have killed off the entire hospital if they fell into the wrong hands. Iron hooks that looked as if they had been made by an old-fashioned blacksmith were screwed all along the opposite wall. They were all different sizes and brushes and mops hung from each of them, attached by plaited string, all so filthy that Selma optimistically assumed the cupboard was no longer in use. It was just a superfluous space in a gigantic hospital complex that would soon be razed to the ground. At any rate, the hospital was to be relocated, sparking such voluble protests from a virtually united medical profession that she thought they must be right. Here and now, though, she changed her mind. Twenty-four hours in a ward far higher than it was wide, with three gabbling wardmates and a sickly smell of urine from the shared bathroom, had made her long for the far newer National Hospital where a year ago she had spent six weeks and eventually come to enjoy it.

She was sitting in a wheelchair without really knowing why. The nurse had insisted. Smedstuen’s bulky thighs spilled over the sides of a flimsy tubular chair and he kept wriggling. On the shelf beside them, he had placed an iPhone in sound recording mode between a bottle of lye and a four-litre drum of undiluted ammonia.

‘As I said,’ he continued, ‘this is just a preliminary, absolutely informal interview. The case is top priority. We’re all over it. A Member of Parliament killed in broad daylight. Reminds me of Sweden, in fact. I thought you’d be keen to add your pennyworth. You know …’

Selma made no response. Something about this guy affected her. It was clear he had respect for her – he had opened the conversation by expressing his admiration and regard for Selma’s earlier feats. She had greeted him with her usual friendliness and cordiality when he had arrived unannounced at her bedside. It was automatic: she fell into the role of her other self in dealings with everyone except a small handful of people. Affable and amusing. A bit of a flirt and always agreeable. It worked every time. But not with this man. There was something reserved about him, something aloof – as if he really couldn’t care less. As if even in a case like this, a fatal shot fired at a crowd of people in an open street, fundamentally bored him.

Maybe he just felt uncomfortable. He was big, heavy and unkempt. His pilot’s jacket was a touch too small. His hair was slightly greasy. He had tried to conceal the smell of cigarettes on his breath with Fisherman’s Friend lozenges. As for Selma, she had managed to take a shower before he called in, her arm taped up with plasters. Vanja had dropped by with clean clothes from her apartment, Armani jeans and a midnight-blue oversized Acne shirt. Sighing deeply, the policeman shrugged as he shifted the mobile several millimetres closer to her.

‘A single shot,’ he declared. ‘You’re certain of that.’

‘Yes.’

‘Eye witnesses heard more than that. Some say two, others three. Still others think it might have been an automatic weapon. A number of shots in a series.’

‘Witnesses tell lies. We humans are chronically unreliable. We make up pictures in our heads that are far from correct. Have you heard of —’

He interrupted her with an impatient toss of the head.

‘Yes, of course. But what makes you so sure?’

‘My ears. I heard one shot. Only one. And that’s what the forensic investigations will show you. One bullet. It hit the back of Linda’s head, changed direction inside her brain, flew out again and then hit me in the arm. Where it lodged.’

The policeman smacked and licked his lips.

‘What’s left of the bullet has been sent for examination,’ he said, nodding towards her shoulder. ‘We got it straight from the operating theatre. It’s so deformed we’ll be lucky if it’s at all possible to work out what type it is.’

‘But we’re talking about a high-velocity small-calibre gun, are we not?’

‘In all likelihood. Which demands a good marksman. A heavy-calibre weapon would have blown the head off your friend. Where did you learn this? About firearms and calibres and suchlike, I mean?’

Selma did not find it necessary to answer. The policeman, obviously feeling increasingly uncomfortable, was tugging at his shirt collar, even though it was open. Scratching his three-day-old stubble. He seemed really completely uninterested in both the case and Selma Falck herself.

‘We’ll see what the technicians find out,’ he muttered. ‘Strictly speaking, we can’t know whether it was you or the other woman, condolences by the way, who …’

He touched his breast pocket, as if searching for a notebook.

‘Linda Bruseth,’ Selma helped him out.

‘Yes, Linda, that was it. We don’t know whether it was you or her who was the target of that bullet. Or anyone else. That woman Varda, for example.’

‘Vanja. Vanja Vegge doesn’t have an enemy in the world. She’s a friendly psychologist that everybody loves. The only provocative thing about Vanja is her colourful, fluttering clothes. Hardly something to get killed for.’

Smedstuen mumbled something that might mean even the police felt Vanja Vegge was an unlikely target for an assassin.

‘It doesn’t have to have been anyone at all,’ he went on. ‘It could have been an act of terrorism. A shot in the dark, intended to scare people.’

Selma laughed, jarring the stitches where she knew a drain had been inserted. She grew suddenly serious and settled her arm more comfortably in the sling. Tried to relax her hand, as she had been told to do.

‘An act of terrorism,’ she repeated. If the policeman wouldn’t buy her affability, he would certainly catch her irony instead. ‘Exactly. It was a typical act of terrorism, of course. Settling down to fire off a single shot at a pavement restaurant. Where there were probably about thirty people seated. And where only I, by chance the only famous person in that whole crowd of people, was hit. Before the terrorist packed up his gear and sneaked off in all the confusion. Yes, of course.’

‘Not only you. Linda …’

‘Bruseth,’ Selma finished for him when he hesitated again.

‘Yes. She too was hit. Two birds with one stone, so to speak.’

‘Obviously because she suddenly leaned forward. She was trying to save a glass of water that was about to topple over.’

‘We’ve heard that, yes,’ he said, nodding apathetically. ‘That other friend of yours …’

Once again he patted his chest.

‘Vanja Vegge,’ Selma reminded him.

‘Precisely. I talked to her yesterday. She says the same as you. One shot, and a sudden movement from Linda. Almost simultaneously.’

‘As I said, it—’

‘All the same, she could have been the target.’

This time, Selma contented herself with a smile. ‘Linda was the most anonymous backbencher in Parliament,’ she said.

‘Yes, but—’

‘From Indre Vestfold, as kind as the day is long and …’

Selma was about to blurt out that the old handball goalkeeper was a bit simple, but caught herself in time.

‘… with such a sunny disposition. You could wrap her round your little finger with no trouble at all. If anyone really wanted to murder her, I could come up with better methods for you on the spot. Much better than a sniper lying hidden in Grünerløkka firing a shot into a café, I mean.’

‘That also applies to you.’

‘Me? What do you mean?’

‘That there are simpler ways of killing you.’

Selma leaned forward in the wheelchair. ‘About this time last year, I was walking around naked on the Hardangervidda,’ she said softly. ‘For five days. In a snowstorm. With serious injuries. With no proper food and drink for three whole days and nights. I’m not so easy to kill.’

The policeman reached his hand out to the mobile, but changed his mind.

‘It’s too early to say what actually happened,’ he sighed. ‘We want to conduct a reconstruction as soon as you’re able for it.’

‘Any time at all. If I’m not discharged today, I’ll sign myself out. This wheelchair stuff is just nonsense. I can walk.’

Selma was fed up. Despite the size of the cupboard, all of a sudden it seemed more confined. She wanted to get away. Her arm was sore, but not so bad that that she couldn’t just as well take some Paralgin Forte and rest on the settee at home for a couple of days.

‘Would you like police protection?’

‘What?’

‘You’re obviously convinced the shot was meant for you. We’re not so sure. But if you believe that someone is willing to shoot you in broad daylight, then maybe you need—’

‘No, thanks.’

Selma was lost in thought. The idea that struck her immediately after she was shot had slipped her mind by the time she had been driven to the hospital and operated on without delay. It had not been able to find its way back through the morphine fog until now.

‘Shit,’ she whispered.

‘What?’

‘Nothing,’ she brushed it off.

The episode at Grünerløkka had been splashed all over the headlines for more than twenty-four hours. Nevertheless, Anine, Selma’s daughter, had not been in touch.

‘Shit,’ she formed the word once again with her lips without making a sound.

The policeman pulled a bag of Fisherman’s Friends out of his jacket pocket, dug out a lozenge and used his stubby fingers to drop it in his mouth.

‘So you don’t want protection, then. OK. We’ll come back to that. Who knew you were to meet your friends at that particular café?’

‘What?’

‘You heard me. Had you told anyone you intended to meet up at that particular pavement restaurant at that particular time?’

Selma shook her head slightly. ‘No, I don’t think so. Well, of course we had said it to each other, naturally.’

He did not even smile. ‘Are you sure?’

‘I think so. Or …’ She gave it some thought. ‘The arrangement was made on Monday,’ she said after a few seconds. ‘Via text message. I live alone, and I can …’

Yet another pause before she shook her head.

‘No, I haven’t spoken to anyone else about that appointment. No one apart from the two women I was to meet.’

‘Have you written it down anywhere?’

‘No. It’s nowhere other than on my list of texts.’

‘No automatic diary on your mobile?’

‘No. Of course I appreciate why you’re asking, but I think I can swear to it that I didn’t tell anyone at all.’

‘Who do you think the others could have mentioned it to?’

‘I’ve no idea!’

He was sucking noisily on the lozenge. ‘Who could have known the three of you were meeting?’

Selma really had to pull herself together to avoid expressing her disapproval. He kept smacking his lips and the strong smell of peppermint was almost unbearable in a space already reeking of damp and cleaning products.

‘Linda’s husband, maybe. Ingolf. He doesn’t live in Oslo, but as far as I know they had a good relationship.’

It suddenly struck Selma that she ought to phone him and express her condolences. It had not occurred to her before now and she lost her concentration for a moment.

‘I see,’ the policeman said, rotating his hand to get her going again.

‘Usually Linda went home to Vestfold at weekends,’ Selma continued. ‘And she spoke to Ingolf every day by phone. As far as I’m aware. There could also have been someone at the Parliament who knew. Maybe they have a system where they have to report their activities and whereabouts. In case of voting and suchlike, I mean. I don’t really have a clue. You’d have to check.’

‘Isn’t your husband also a Member of Parliament?’

‘Ex-husband. Yes. But I don’t know what routines they have. As I said, you’d have to find out for yourself.’

‘I’ll do that. Vanja, then, what about her?’

‘You can ask her yourself.’

‘Yes, but now I’m asking you.’

Selma sighed. ‘Vanja is married to Kristina. They have a symbiotic relationship. They lost their only boy a couple of years ago and since then it’s been almost impossible to get one to come to anything without the other. Kristina should actually also have been with us at the café, but she had a sore throat. Anyway, I’ve got a pretty sore arm, so I hope we’ll soon be finished with this.’

Now he had begun to jot down some notes. ‘Uh-huh,’ he said inconsequentially. ‘Uh-huh.’

All at once he looked up and straight into her eyes. ‘Do you have any enemies?’

Selma’s eyes narrowed. She hesitated. ‘I think you’re right,’ she said instead of answering him. ‘It was probably Linda who was the target.’

‘Why do you say that? Three minutes ago you scoffed at the idea, and I—’

‘Despite all that, she was a Member of Parliament. An important person. And we’ve agreed that the sniper was an expert. So it was hardly a bad shot.’

‘We’ll come back to all that,’ the police officer said in annoyance. ‘Please answer my question.’

‘Which one?’

‘Does anyone wish you harm? Enemies of any kind?’

Selma tried to look bored. It was extraordinarily difficult. More than anything she felt compelled to phone her daughter Anine and make it crystal clear that Linda Bruseth had been the one who was the assassin’s target. Selma had just been terribly unlucky. What were the odds, in fact – it would never happen again.

‘Two or three years ago I would have said no,’ she told him in the end. ‘I mean, my ex-husband and children have not been exactly over the moon about me for a while, but they don’t really wish me any harm. I assume. Apart from that, I have only friends. No enemies. I believe, at least. But right now?’

She made a face. He stared at her, straight into her eyes. There was a glint beneath the bushy eyebrows that merged above the bridge of his nose into a bristling V. His gaze was suddenly razor sharp, as if up till now he had tried to trick her by seeming different from the way he was. Selma cocked her head.

‘I would certainly claim to have enemies now, yes.’

He did not blink. Selma felt an increasing aversion. It was as if he was holding something back. As if he had arranged in advance with the nurse in charge to borrow this horrible broom cupboard as an interview room. And to force her into a totally unnecessary wheelchair to make her weaker than she actually was.

‘In addition to an extensive secret paramilitary organization,’ she began, ‘with resources and weapons and—’

‘Operation Rugged/Storm-scarred was destroyed last year. Thanks to you.’

‘Destroyed?’

It was difficult not to laugh again. ‘You think it’s possible to destroy such an outfit?’

‘Well, yes, after all, there was such an infernal racket, and a whole string of court cases, political scandals, lots of—’

‘You asked me if I have enemies,’ she broke in. ‘I’m trying to answer. Rugged/Storm-scarred was an operation. The actual organization was nameless, in fact. Ill-defined. Impossible to grasp. I’m convinced there are still people out there who wish me six foot under. On top of that there are loads of folk in the Norwegian cross-country community who would be delighted if I suffered real misfortune …’

She had started to count carefully on the fingers protruding from the chalk-white sling.

‘But they’d scarcely lie on the roof of a building to shoot you,’ Fredrik Smedstuen said. ‘If they had, they’d have to be biathletes.’

He smiled for the first time. His teeth had a greyish tinge.

‘We also have an angry diamond thief,’ Selma said, impassive, pointing at the ring finger of her left hand. ‘But he’s behind bars. Late last winter, when I could at last move about after last year’s little … trip to the mountains, I exposed a disloyal employee in Telenor. He’s still on the run, but the last reported sighting was in Bali. Probably won’t dare to come home again for a while. And then we have—’

‘You don’t need to go though all your cases. I get the picture.’

‘In addition to all of these, you have the people I’ve turned down.’

‘Turned down? You mean—’

‘No, not men. Not like that. Clients. I get five or six applications a week. At least. I accept one case every other month or so. Some of the ones forced to leave with unsettled business can get quite agitated.’

She shrugged her uninjured shoulder and added: ‘Which I can well understand.’

‘What are you working on now?’

‘Now? Right now I’m sitting in a broom cupboard with you, wondering whether we’ll soon be finished. My arm is aching and it stinks in here.’

Heaving a sigh, the policeman got to his feet with some difficulty.

‘Stay in Oslo, then. In principle, by the way, you have the right to a victim’s advocate to represent you.’

Selma shook her head. ‘No, thanks. I’m sure I’ll manage. I’m fairly sure now it wasn’t me the man was after.’

She felt how much easier it was to tell a lie rather than speak the truth.

‘Or woman,’ she added quickly. ‘To be fair, we don’t know the sex.’

‘Call me when you feel up to a proper interview. At Police Headquarters. And a reconstruction, as I said. I guess that will be pretty soon.’

He opened the door to the busy sound of footsteps and talking and the occasional shout. The perpetual odour of sixties-style dinners lay thick in the corridor. Since her operation, it had made her feel queasy. However, compared to the putrid floor cloths the smell of industrial meatballs was heavenly.

Fredrik Smedstuen stood with his big hand on the door handle. ‘You didn’t answer,’ he said.

‘Answer what?’

‘What sort of case you’re working on at the moment?’

Selma hesitated. A slip-up. A good lie sprang to her lips, smooth as silk. Never too detailed, but not so brief either that it offered the opportunity for further questions. It came of its own accord, without delay, precise and utterly effortless.

‘Nothing,’ she said abruptly, compensating with a smile so broad and dazzling she could swear it brought a blush to the Police Inspector’s cheeks.

The Smiley Face

Her shoulder and upper arm were throbbing like mad when Selma Falck finally stood in front of the entrance to her own apartment in Sagene. Five well-wrapped bouquets of flowers were propped against the wall between her and her neighbour. She instantly assumed they were intended for her, since the media had given detailed reports of the shooting episode at Grünerløkka on all platforms. To top it all, DGTV had started broadcasting from the crime scene only twenty-two minutes after it all happened. The sensation caused by a Member of Parliament being killed in what appeared to be a straightforward assassination was immense enough in itself. The immediate rife speculation that Selma Falck was the intended target made the story even more riveting.

As always, Selma was in the spotlight. She had left behind sixteen floral arrangements at the hospital. The auxiliaries had run out of vases after the last one arrived this morning.

Using her right hand, she rummaged in her bag for her keys. She noticed her fingers were tingling and realized the slight trembling in her right arm had something to do with the injury in the left one. She caught herself wishing Lupus were still alive. The half-wild dog that had saved her life a year ago had passed away a couple of weeks after their rescue. Warmth, food and care after what had turned out to have been six months alone on the mountain plateau was too much for the old animal.

Lupus had looked after her. Now she would have to look after herself.

After fumbling to insert the key in the lock, she rotated it. First one, then the security lock. She opened the door a crack.

Someone had been here. Again.

There were many ways to check whether an uninvited person had visited a place. An alarm system was obviously the simplest. When she had moved into this new building in Sagene almost two years ago, it had all been already installed. Not exactly state of the art, but OK, and Selma had not seen the point of cameras in the small apartment. The system was new and good enough. All the same, three weeks ago she had come home and felt a disquieting awareness that someone had been there. Inside her home. Inside her modern, secure apartment, where there were only two ways in. One through the front door, the other via the balcony, the only one of its kind on the smooth exterior wall, suspended more than eight metres above the ground. Neither of the two doors showed the least sign of a break-in. The idea that someone might have climbed up the front wall in a densely populated area without drawing any attention was difficult to imagine. Impossible, actually. The person in question would have had to enter through the front door. Which meant he or she had a key. You could of course enter the building by waiting for a careless resident who left the door slightly open, but Selma’s own apartment was something else again. The person in question would have to possess a key and somehow switch the alarm off and then back on again.

No one else had a key to her apartment as far as she knew. No one knew the code for the alarm. To the best of her knowledge.

In what felt like a lifetime ago, during the period before she almost lost her life on the Hardangervidda, she had been involved with a young man. A far too young man for a middle-aged woman like her. In a moment of thoughtlessness, she had given him a set of keys. He had handed them back when she had brutally broken up with him, not because she wanted to, but because it was necessary. He had simply left them on the hallway shelf one day and disappeared. Since then she had not seen him. He had never been given the alarm code. When she had finally been discharged from hospital at the end of October, she had tried to contact him. Without success. Whether it had been wounded vanity or a slightly broken heart that took hold of her she was never completely certain.

When she had been suffused with this disquieting feeling about uninvited guests three weeks earlier, she had not entirely understood why. It was only a feeling. It struck her as soon as she stepped foot in the apartment, even though nothing had been disturbed. At least as far as she could see. It was all like a paranormal shift, a vague stirring of a foreign substance. Not a smell, nothing visible. A sort of presence was how it seemed and she had felt her pulse rate soar when she walked on into her bedroom.

No sign of a break-in there either. Eventually she had dismissed the notion. She had changed in the last year. Become a touch more anxious. A bit jittery, even though she never showed it to anyone. She had begun to consider death. Anything else would have been strange: Selma Falck had literally been minutes from the hereafter when she had finally been found by a mountain rescue patrol last autumn.

Maybe it was just her age.

So she had written it all off as sheer fantasy, until she was about to turn in for the night. The bed was not made. The single quilt was curled up against the pillow, and when she lifted it, she caught sight of the packet of chewing gum.

A packet of KIP.

Three small, rectangular pieces of gum, red, green and yellow, tightly wrapped in cellophane.

She had shaken the pillow after she got up. It was plumped up and in the right place, with no sign of a hollow made by her head. In the middle, in a tiny depression someone must have used two fingers to make, lay the packet. The best treat Selma Falck had known when she was little.

She had loved KIP. The taste, fruity and far too short-lived, but also the consistency, was worth all the pennies she managed to rake in for want of regular pocket money. The tabs were crisp, almost floury, at the first chew, before it melded into a perfect, rubbery balance between hard and soft. After only a few minutes they were usually exhausting to chew and had lost their flavour into the bargain, but those first few seconds of a KIP held such good memories that she felt a faint cramp in her jaw at the mere sight of a packet.

The small tabs had not been in production for forty years or so.

Selma had never clapped eyes on a packet since then.

But now one lay here on her pillow.

Several seconds of total bewilderment were succeeded by an unfamiliar dread.

It had washed through her so intensely that she had not even dared to pick up the packet. For a long time she simply stood and stared. In the end she took the second quilt and pillow from the other side of the double bed and lay down on the settee. Without being able to catch a wink of sleep.

There were only two people on the face of this earth who could know that Selma Falck, as a young girl, would have gone through fire and water for a packet of KIP. Vanja Vegge, her oldest friend, and Selma’s little brother Herman.

It was out of the question that Vanja had broken into Selma’s apartment without leaving a trace. She did not have keys and did not know the code. Herman had died years ago.

Following a sleepless night, she had dismissed the thought of calling the police. With her background, they would probably take the incident seriously, despite the strangeness of the threat, but on second thoughts it occurred to Selma that it had not really been a threat at all, strictly speaking. It revolved around a packet of chewing gum that had been discontinued long ago. It might all be a bizarre joke. No harm had been done, apart from the annoyance of being scared. Selma had spent weeks and months giving statements in the cases proceeding from the exposure of the Rugged/Storm-scarred operation. The desire to pay any further visits to police headquarters at Grønlandsleiret 44 as soon as this was far from compelling. When daylight forced its way through the gap in the living room curtains around half past five in the morning, she was no longer afraid.

Nevertheless, she had embarked on the potato flour trap. A fine layer of powder on the pale oak flooring just inside the threshold before she went out, closed the door and locked up.

For three weeks she had continued with this. With no fresh signs of uninvited guests. In the past forty-eight hours there had been other things to think about, and the piles of floral bouquets had almost made her forget to take care as she moved inside. Fortunately she had thought of it before she opened the door.

Someone had stepped on the potato flour. Selma had to crouch down to see the partial footprint, a barely visible tip of a shoe. When she pulled her glasses down her nose and studied the print more closely, she was so startled that she fell back. Her throat constricted and she had to breathe through her open mouth. Her head was spinning when she finally dared to kneel down and examine it for a second time.

Her eyes had not deceived her.

The toe tip had formed a zigzag pattern in the potato flour. That was terrifying in itself. What was worse, however, was the smiley face beside it, maybe five centimetres in diameter and drawn with something slimmer than a finger.

Selma stopped breathing altogether when she spotted that the emoji was winking boldly at her.

The Memorial Service

The Labour Party’s parliamentary group had chosen to tone down the memorial service as much as possible.

Linda Bruseth was a name people outside her home region had scarcely heard. Her road to the Vestfold bench in the parliament building had started in small ways. In a tiny inland village she had been repeatedly re-elected as chair of the school’s PTA thanks to her parentage of a bunch of five boys. That lasted for more than fifteen years in total, and when the last child waved goodbye to the farm to venture into the big city, her existence became unbearably bleak. She found something else to fill her days. After her triumphant efforts in a popular movement to stop the compulsory acquisition of three properties in connection with a planned wind farm up on the moors, she ended up on the Labour Party’s list for the local council elections. In the secure surroundings of her local area, she did a magnificent job. She knew everyone and was well liked by her opponents as well as her party comrades. Tall and heavy but nonetheless athletic, as she had always been. A great lass, people said of Linda Bruseth – a bridge builder of the old-fashioned kind.

Always a smile, always something to give, for everyone.

During the huge surge of refugees in the autumn of 2015, Linda resolutely took charge. An old meeting house and a recently closed-down hospital were transformed within a fortnight into reception centres. The village opened its arms and welcomed Syrians and Afghanis with warmth and enthusiasm. At the same time they created twenty badly needed job opportunities in the village. It all became so efficient, inclusive and successful that Linda Bruseth, prime mover of the project, was invited as a guest on to NRK’s flagship TV programme, Kvelden før Kvelden: the day before Christmas Eve 2015, in a miasma of crisp roast pork ribs, between Christmas carols and lavishly decorated trees, Linda and two handsome little boys from Syria sat smiling.

Heart-warming, people commented on social media.

At long last, an empathic Labour Party politician, wrote others.

She would persuade me back into the party, at any rate, observed quite a few.

Linda Bruseth was that rare thing, a results-oriented politician. Throughout 2016, she grew increasingly popular across the region and early the next year she was nominated to a secure place on the Vestfold Labour Party’s list of candidates for the parliamentary elections later that same year.

Only to plummet into oblivion once elected.

She was allocated a place on the Justice Committee, but had no clue about legal matters. She was used to sound common sense and resolute action in a familiar environment, not screeds of documents in the big city. She was so uncomfortable in her new role that she made sure to be moved as quickly as possible and her next stop was the Rural Affairs Committee. However, she did not feel at ease there either. For the first time in her life, she admitted to a diagnosis. Dyslexia. For more than fifty years she had managed remarkably well despite her secret difficulties with reading and writing, but now they had really begun to bother her. In the end, only a few months into a four-year period everyone now knew would be both her first and last stint, she was tucked away into the Family and Culture Committee.

There, things went slightly better.

Children were a topic of which the mother of five had a good grasp. Sports also. But culture was not her strongest suit, and she still had problems with reading.

In the statistics of talkative representatives, she was at the very bottom.

And now she was dead. Shot in a café because she got in the way of a bullet meant for the far-more-high-profile Selma Falck.

The Party had chosen the lobby for the brief memorial service. A space in the middle of the parliament building meant, perhaps appropriately, for comings and goings. Admittedly, it also served other purposes, both formal and informal, and not least was a hunting ground for the press pack every time a political storm was brewing, when politicians would really prefer to hide away.

Faint individual voices had been raised in preference for the Labour Party’s group meeting room. They felt that would be a touch more caring. Smaller and more intimate. Some claimed it would give stronger emphasis to Linda Bruseth’s connection to the Party. Such objections were dismissed without further discussion.

This was something that simply had to be done. The Party’s most anonymous representative would receive her small mark of respect, without laying the groundwork for anything more than a minimum of comment on an unfortunate member. Although it was true that the press were far kinder to dead politicians than they were to the living, there was every reason to spare the family from seeing the insults already appearing on social networks.

Lars Winther, news journalist on the Aftenavisen newspaper, stood in one of the large arched corridors beside the doors to the assembly hall. He had come alone, without a photographer. Some photographic service or other would probably offer something. He was in a bad mood because he had not been allowed to visit Selma Falck. Since the time a year ago when she had presented him with the journalistic scoop of the century, the two of them had become even better friends. Such good friends that his editor would not permit him to have any professional contact with her whatsoever.

Instead he was now listening to the leader of the Parliamentary Party rattling off a eulogy in front of the sparse assembly. The politician had delved deep into the member’s past to find suitable and relatively truthful words of praise. Beside him there was a small table with a burning candle and a book of condolences in which no one had written. When he had finished, he scribbled down a few words of farewell and handed the microphone to the oldest of the members from Linda Bruseth’s home region. He launched into a speech of which the introductory words at least contained considerably more warmth than the previous speaker’s. And of course he had also known the deceased politician for more than twenty years. Kind was a word that was repeated in every second sentence.

Lars Winther felt a nudge in his back and wheeled round in irritation.

‘Hello,’ muttered a colleague from NTB. ‘This is not where it’s happening, you know. You can see that for yourself. There should have been a lot more of a commotion about an MP being murdered. This stuff here is just embarrassing beating around the bush. It was Selma Falck who was supposed to die. Not Linda Bruseth.’

When the speaker in the distance stopped abruptly, a vague sense of confusion spread through the gathering. Lars took a step out into the lobby and craned his head forward. At the opposite end, the President of the Parliament, who should really have been present at the memorial service, was walking towards them with determined footsteps. Behind her were four men and one woman Lars did not recognize. Their stride, the look on their faces and the fact they were almost marching in step, however, meant he immediately understood who they were.

‘Well, the police at least have their doubts,’ he said under his breath to his cocksure colleague. ‘As far as they’re concerned, this is not so cut and dried. They’re on their way to search Linda Bruseth’s office.’

The Graveyard Walker

It was late and darkness had settled over Oslo several hours ago. A drizzly rain was falling from the leaden low-lying clouds. The path was slick with wet leaves. Even though the days could still be warm, the first frosty night was probably not far off. The man approached the graveyard from the west and had crossed the motorway through an underpass. His left knee ached less than usual. He tried to walk steadily, without a limp. If he overtaxed the right leg, it would become painful too.

Not a soul to be seen.

He walked slowly between the graves. Here and there, people had placed battery-operated lights that created a gloomy, sinister atmosphere. As usual, he had a grave candle in his pocket, along with matches and a packet of cigarettes. Stopping for a second, he fished out a smoke and stood in the shelter of an oak tree with his hands curled round the match he had torn off.

They should have stopped, the two of them. Both he and Grethe. All through the nineties, fewer people around them smoked. Even when his wife was diagnosed with lung cancer with metastasis in 2002, they had both continued. Grethe just could not put the cigarettes away and by then there was hardly any point in him doing so either. Anyway, he was absent most of the time.

When she died the following year, he switched to smoking in secret. In addition he stopped drinking. Not that alcohol had ever been a problem for him, but when he buried his wife, he entirely lost the pleasure in taking a glass or two. Instead the tiniest drink pushed him down into a darkness he found increasingly difficult to crawl back out of. So he stopped, just as he had cut out almost everything else in the painful numbness of having become a widower.

Apart from smoking, and then only when no one else saw him. And his work. He continued until the age of fifty-five, when he had received a gilt-edged opportunity to retire. Since then there had been plenty to occupy him, as he possessed a sought-after expertise. The social side was not so successful. Grethe had been the gregarious one and she had seen to everything on the home front. House and family and social company. The boy and the garden and finances and everything associated with family life.

His existence had taken a slightly too sudden turn for the worse when she succumbed and died. Only by the skin of his teeth had he managed to get through it without giving up the ghost. Even now, so many years later, he never felt really happy. Life had become sepia-coloured, but there was still momentary comfort to be found in the very first drag of a newly-lit Marlboro. The glowing tip gave off a cheerful light as he took a mega-drag and walked on.

The marble stone was small, low and roughly hewn, just as Grethe had wanted it. In a thick envelope on the bedside table, adjacent to the bed where she had drawn her last breath, instructions had been left. The contents were straightforward and mostly practical, dealing with the title deeds to the house and spare keys for the cabin. Insurance documents and family jewels and the agreement with their neighbour about dividing the road that nothing would come of. Nevertheless, between the lines, he also read into this the odd glimmer of deep love, of harmony and twenty-one good, secure years.

Grethe lay at the very far end, the farthest and lowest point in a burial ground surrounded by heavy traffic and light industry. The stone leaned a little to the south-west, where the fjord lay, as if it longed to go home to Italy from whence it had come.

Her name was on a bronze plaque. The letters were relief engraved on a narrower panel screwed on to the larger one. There was something un-Norwegian about it – the usual practice was to engrave the name and dates on the actual stone. But this too was something his wife had decided before she died. Maybe she had seen it somewhere abroad.

He hunkered down though the pain in his knee brought tears to his eyes. Thirty squats a day were still routine for him despite no discernible improvement coming of it. The day he skipped his morning gymnastics, however, everything would be knackered. He would never manage to get down into that position again. It was unthinkable to let oneself deteriorate like that. Of all the little things that still made everyday life move on from one date to the next, the satisfaction he derived from keeping himself trim was among the most important.

His fingers ran over the ice-cold lettering. The bronze plaque, which until a few weeks ago had been dark green, almost black in some places, was recently polished to a golden shine. Beneath Grethe’s name, a space had been cleared for another. He had been present when the stonemason had re-attached the plaque.

The patch of ground beneath the colossal elm tree had become a grave for two.

The name at the bottom had not yet been fitted. The guy from the undertakers had seemed taken aback when the widower had turned down the idea of screwing on the second plate. Servile and silent, he had nevertheless accepted the instruction and handed over the small panel with the name and dates of birth and death. It was at his home now, where it would remain, wrapped in tissue paper in Grethe’s old bedside table drawer, until it was all over. Until everything had been accomplished and it was possible to breathe again.

This was the only thing he wanted in life now – to be able to take a deep breath down into his lungs and let it leak out again slowly. Time after time. Feeling the life-giving oxygen circulate to the many muscles of the body, making him feel alive. He did not know what was going to happen. It didn’t matter. In truth, he had made unforgivable mistakes in his life, but far greater wrongs had been inflicted on him and his little flock.

He had lost far too much.

If only Grethe had been allowed to live, the world would be different.

He mumbled a few words and slowly rose to his feet. Lighting the grave candle he had brought, he set it down on the wet, dead grass. Perhaps he was saying a prayer. He was not entirely sure. It was probably Grethe rather than God he was addressing. In the end his thoughts petered out.

Once again he fished out a smoke and sauntered back the way he had come.