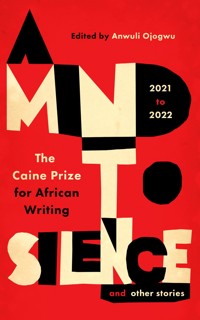

A Mind to Silence and other stories E-Book

11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A woman who carries her fate and that of her community in her hair is beguiled by the deceptive designs of Europeans out to colonise her most prized possession. A man finds happiness in the reincarnation of a lost love. A young woman risks her life for freedom through the cultural practice of a human loan scheme. Tales of sacrifice, love, freedom, self-discovery and loss fill the pages of this larger-than-life tapestry of stories from across Africa and its diaspora. Forged in a diversity of tempers and forms, these stories range from the epistolary to the experimental, from mysteries, noirs and political thrillers to speculative fiction and futurism, and much more. In prose that moves from visual and lyrical to gritty and visceral, these writers explore fate, memory, the fragility of love and the duplicitous nature of human interactions

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

A MIND TO SILENCE AND OTHER STORIES

AKO CAINE PRIZE ANTHOLOGY 2021-22

Edited by Anwuli Ojogwu With a foreword by Okey Ndibe

Table of Contents

Foreword

An air of history surrounds this year’s edition of the AKO Caine Prize. After close to two years of global disquiet occasioned by a viral pandemic, 2022 held out some promise of restoration – a slow yet heartening reclamation of normalcy. Or, at any rate, a semblance of what was nearly lost.

It’s said that life is short but art long. One proof can be found in the sheer profusion and vitality of the short story entries for 2022. The 349 submissions, and 267 eligible entries that contended for this year’s AKO Caine Prize represented a record. They surpassed by far the totals for previous years.

What was the import?

For many African countries, Covid-19 was a public health and economic nightmare. Yet, by some fortuitous and inexplicable quirk, the virus did not unleash on the continent anything approaching the Olympian scale of devastation forecast by epidemiological experts.

By contrast, on the strength of this year’s entries, it appears that the pandemic may have fertilised Africans’ literary creativity. The marvel did not lie alone in the impressive count. All the judges – myself, Elisa Diallo (an academic, author and publisher of French and Guinean descent); Angela Wachuka (the Kenyan co-founder of ‘Book Bunk’); South Africa’s Lethlogonolo Mokgoroane (co-founder of ‘The Cheeky Natives’); and the UK-based Nigerian visual artist, Ade ‘Asiko’ Okelarin – were taken by the technical sophistication, stylistic poise, and thematic diversity of a fair number of the entries.

In story after story, the adeptness of touch, freshness of perspective, originality of language, and depth of insight sustained a sense of encounter with something akin to orchestral splendour. The authors hail from various geographic locations and cultures of Africa – East, West, North and South – as well as the global African diaspora. The entries are inspirited by animist, secular, Christian and Islamic ethos. Some stories are as stubborn in staking out political and historical grounds, as others are unabashed in their disavowal of such animus. Taken together, the authors represent a broad pan African tapestry. And the collective harvest is nothing short of a narrative smorgasbord. The stories are forged in a diversity of tempers and forms: mysteries, detective, noirs, the epistolary, futurism, political thrillers, experimental, the good old traditional mode.

Given the magnificent scandal of narrative riches before us, the task of selecting a shortlist of five stories proved particularly – predictably – arduous. To their credit, the judges were willing to be painstaking. They approached the task with a winsome combination of grace and patience – and a dollop of humour.

It took nearly four hours. I’d be the first to confess that the challenge of whittling down nearly 300 stories to five contenders is forbidding to the point of futility. Any group of five judges might have come up with an entirely different slate of finalists. There’s certainly something inscrutable and mystical in the way any reader responds to a story.

In the end, I believe the time my fellow judges and I put into deliberations was well rewarded. I’m proud of the five stories on our shortlist: Idza Luhumyo’s Five Years Next Sunday, Nana-Ama Danquah’s When a Man Loves a Woman, Hannah Giorgis’s A Double-Edged Inheritance, Joshua Chizoma’s Collector of Memories, and Billie McTernan’s The Labadi Sunshine Bar.

The varied soils in which the stories are rooted mirror the variety of their styles and themes. In that sense, they inhere a measure of the stupendous vastness and diversity of the broader corpus of entries. In Luhumyo’s story, a woman who carries her fate and that of her community in her hair is beguiled by the duplicitous designs of Europeans out to colonise her most prized and vulnerable possession. Danquah hews a heartbreaking narrative of the tragic outcome of a love deadened by illness and toxic suspicion. In her story, Giorgis limns the intersection between fate and a reckoning with gruesome wrongs that must be avenged. In Chizoma’s story, a few women come to terms with the terrible consequences of a long-ago heist of a baby-girl. McTernan serves up a tableau where desperate and dream-fuelled women must contend with their fellows and lovelorn men if they must win their fortune – or lose everything.

Placed side by side in this anthology, the stories both reveal their individual genius and intriguing thematic linkages. That revelation came to me in retrospect. But the attentive reader is bound to glean from these five stories a sense both of their profound distinctiveness and shared exploration of the themes of fate, the embodiment and contestations of memory, the ubiquitousness of duplicity in human interactions, and the fragility of love.

Okey Ndibe Chair of Judges, 2022 AKO Caine Prize

Preface

One of the highlights of the 2022 AKO Caine Prize Workshop was watching a documentary with George Saunders, one of the finest short story writers in the world, on making a story. In the documentary he made a poignant point that ‘the discontent with writing urges it to a higher ground’. This would become evident during the workshop, as I watched the evolution of the writers from anguish, hope, and then a sense of release when their stories finally took form. It is the nature of the creative process to experience torment and pleasure until the story is born, and for nine days, the workshop sessions were both gruelling and inspiring. I had the privilege of working with these writers, alongside award-winning writer and 2020 AKO Caine Prize shortlisted writer, Jowhor Ile, who served as the writing tutor. Together, we nurtured their ideas and helped them realise the stories that they wanted to tell.

On the topic of release: the last two years, with a raging pandemic, have been difficult ones, leaving in its wake loss, despair and isolation, and the timing of the workshop was a respite from its shackles. It provided fellowship and the sense of renewal that we all needed. The disruptive impact of the pandemic on travel was also apparent in AKO Caine Prize’s decision to pilot a regional workshop by selecting only writers from the ECOWAS region. Regardless, the presence of young emerging writers and an older multi-award-winning writer only enriched the experience with their different perspectives, which will be seen in the styles and themes of the stories in the anthology. There were nine workshop participants from across West Africa: Victor Forna (Sierra Leone), Elizabeth Johnson (Ghana), Akua Serwaa Amankwah (Ghana), Kofi Berko (Ghana), Audrey Obuobisa-Darko (Ghana), Jeffrey Atuobi (Ghana); Onengiye Nwachukwu (Nigeria), Akachi Ezimora Ezeigbo (Nigeria) and Sally Sadie Singhateh (The Gambia).

This sense of release and renewal was not limited to us the participants. Even the AKO Caine Prize workshop emerged from a hiatus since 2018 when it held the last workshop in Rwanda.

Navigating my role as editor each day of the workshop was characterised by many hours of conversations with writers to find the heart of their stories. I watched them discuss their story ideas, craft them, read them to each other, and improve on them with further critique from Jowhor. This was a hard feat as a story will only be told when it is ready to be told, and I commend the writers for their determination. One writer I worked with found her story in a thread of a dialogue between two characters in the second draft of a three-thousand-word piece. She would later discard the rest of the plot and build the story from ground up on that theme, and this eventually became The Loan. Some days, while working with them, I prodded for answers on the direction of a story and sometimes I offered a direction. Notwithstanding, the writers were confident in their ability to agree or object to interventions, which made the process seamless and rewarding.

There was a lot of learning, not just from the workshop sessions with us tutors, but among the writers who learned to lean on each other. They formed a camaraderie and tested their ideas among themselves, reading each other’s stories, offering critique and suggestions for improvement. At the end of the workshop, the stories that emerged were evocative, vivid, and vibrant, written in multi-genres from speculative and literary fiction to mystery and romance.

Readers of the anthology will encounter themes about sacrifice, love, freedom, self-discovery, loss, all expressed in language that is visual and lyrical, bordering on the experimental. From the supernatural reconciliation between two sisters torn apart by their destructive father in Akua Serwaa Amankwah’s Sugar’s Daughters to a man who finds happiness in the reincarnation of a lost love in Akachi Ezeigbo’s Homecoming; and from a young girl who comes of age in a futuristic world of Ghana’s ancient mythology and technology in Audrey Obuobisa-Darko’s Nnome, to a young woman who risks her life for freedom through the cultural practice of a human loan scheme in Sally Sadie Singhateh’s The Loan, among other stories.

Beyond the workshop, the experience was well-rounded. There were other moments to engage with the community and pay it forward with visits to two secondary schools. The writers were spilt into two groups. The first group visited St. Augustine College, which was established in 1930, and the other group paid a visit to Ghana National Secondary School, which was established in 1948, both in Elmina, where they engaged the young students on writing and storytelling and listened to their aspirations.

There was also a visit to Elmina Castle once a trade settlement for goods before it became an Atlantic Slave Trade depot where the writers heard harrowing stories of the cruelty behind the capture and separation of families. In addition, the AKO Caine Prize partnered with The Writer’s Project of Ghana, who organised a public event for the writers at the Goethe Institut where they read and discussed excerpts from their stories. The final night of the workshop activities came to an end with a tribute to the celebrated author and playwright, Ama Ataa Aidoo.

This workshop was memorable because of the generosity of the people we met including Martin Egblewogbe and Mamle Kabu, co-founders of The Writers Project Ghana and AKO Caine Prize Workshop alums; Professor Kwadwo Opoku-Agyemang, an award-winning poet and eminent scholar of Literature at the University of Cape Coast; Jowhor Ile, my partner tutor; and the proprietor of Elmina Bay Resort, Mr Ben Kweku Idun and his remarkable staff, who saw to our comfort in the beautiful environment. It is also in order to recognise the leadership of the AKO Caine Prize director, Sarah Ozo-Irabor, whose gentle guidance lifted the writers’ spirit daily. Her famous quote: ‘Give yourself grace and learn to lean on others when they give you grace’ became a motivational anthem for the writers as they worked hard to meet a tight deadline.

For the last 23 years, the AKO Caine Prize has been instrumental to showcasing African talent and it is my pleasure to present to you the stories from another set of emerging talent from the 2022 AKO Caine Prize Workshop, with two additional stories by Rafeeat Aliyu and TJ Benson (both from Nigeria), participants in the 2021 ‘Online with Vimbai’ workshop – a virtual coaching and editing programme with noteworthy editor, Vimbai Shire. I hope you enjoy the stories.

Anwuli Ojogwu Editor, 2022 AKO Caine Prize Workshop

2021 SHORTLISTED STORIES

1. Lucky

Doreen Baingana

Originally published in Ibua Journal 2021

We’ve been left behind. It’s another morning, so we’re in the school garden looking for lunch. The maize is still too young, too dark a green, but what can we do? It’s not easy reaching for the long bulbs with yellowy wisps like white people’s hair; the leaves cut our arms and legs with their razor-sharp fuzz because they don’t want us to steal their cobs. But that doesn’t stop us; the ache of emptiness keeps us going. Those who pick more will eat more, so we work as fast as we can. All around me, boys scrabble around, making the dry leaves on the ground crackle as loud as roosters. Or does it seem so loud because the rest of the school is silent?

Eh, but hunger can make you do things! Three days ago Ociti and Bosco clambered over the fence and ate like twenty hard green mangoes from the old orchard that is now more like a forest. Rumour says the owners went into exile long ago, England or somewhere. But how we laughed at those two when they spent the whole night running back and forth from the pit latrine! Laughing to cover our jealousy ‘coz at least they had felt full, content, for a few hours. Envious ‘coz they were brave enough to venture out of school, what with all the stories of the Lakwena rebels roaming around, and worse, the new government soldiers who still behaved like the rebels they had been for—was it six years?

This is why school has closed, and why eleven of us are stuck here; we can’t go back to our homes in the north: Gulu District, West Nile. There’s nowhere to pass because of the fighting. Everyone else lucky enough to leave or have relatives in the south has left. My Auntie Joyce is in Kampala somewhere, but I don’t know where exactly and I don’t have her phone number or anything. I tried calling my father, back home in Aboke, to ask, but his number was off, and the Headmaster—‘Big Head’ since his competes with a hippo’s—shrugged as he took the office phone from my hands. That was it: I was staying. And yet he, whose job it is to take care of the school, took off with the rest and left us! He didn’t even turn his hippo head to look back at us as the school bus rumbled out of the gate, packed full of teachers and students like onions in a sack.

Only Mr. Komakech, the mouthy maths teacher, has stayed behind with us. Even the workers have left, can you imagine? Koma, as we call him because he never stops talking, said he wanted to ‘enjoy the war properly’ and laughed, but it seems he’s stuck here too. He can talk us to death, but for some reason, my eyes can’t stop following how his large lips chew around the words like they are tasty.

Don’t ask me what the war is all about: the new government army of former rebels was now fighting rebels who had been the old government army. So what’s the difference? They’ve switched places like we did back home when we were seven, eight, those days: Ugandans versus Tanzanians and the rule was that the Tanzanians had to win because they had saved us from Idi Amin. Oh, but it was wild running through the compounds, scattering the cackling chicken, dogs barking with excitement and joining us as we scrambled through the shambas, wind whistling over and under our shouts: Pow-pow! Got you! Die! Shooting each other dead with stick guns, screaming, falling, then getting up, brushing off the dust and dried leaves, and changing sides. I was really good at falling in slow motion, arms and legs flailing, body jerking in the dust, like the soldiers on Bob’s father’s TV, which he allowed us to watch from the outside, peering in through their windows.

And here I am fighting with maize cobs, against a sun hammering my forehead. Thank God for no barber visits; at least my bushy hair is a sun shield. After picking four cobs, I turn to Ociti: ‘How many have you got?’

‘Five.’

‘That’s enough for now, let’s go.’

Koma has ordered us all to stay in one dorm, ‘to keep each other company,’ he says. ‘Birds of a feather do what?’ And he cocked his head to one side like he too was a bird: tall, dark and smooth. The way he talks, you’d think we’ve remained behind for fun like it’s a holiday at school because we like it so much. Shya! Big Head also called it a ‘free term’, since we aren’t paying fees like he’s done us a favour. As if we’re stupid. Here we are, no assembly, no teachers except one, no cooks or cleaners, no sports, nothing. Free term? How about ‘prison’? Ask me what prison is like and I’ll tell you: whole hours, days, stretching out like an endless line of ants, filled with nothing but the same routine chores, and then sitting around staring emptily at the same few pimply faces, listening to our stomachs growl, our thoughts roaming the carefree past or a fantastic future, circling, circling to avoid the wide, flat, dry now.

To make it worse, Koma does his best to cheat us out of our ‘free term’. First, he makes us get up early. ‘Up, up, you don’t have all day!’ But of course, we do. ‘Early to bed, early to what?’ It’s so annoying to be shaken awake by his bright booming voice and big smile as he pokes his head into our room. But also, something inside wakes up, feels good to be smiled upon by him.

‘Good morning, teacher’ we mutter as we drag ourselves out of bed.

Well, we sleep early because power has gone, and so what else can we do in the dark but listen to our bellies growl? Only Koma has a torch, and we use it sparingly to save the batteries. But surely we could start the morning’s chores at seven, even eight, not six? After fetching water, scrubbing saucepans, floors, the toilets and bathrooms, collecting food, cooking and eating, Koma makes us sit in class straight after lunch. Not even a ka-hour of rest, how unfair is that?

‘Hard work does what?’

Koma seems to look at me more than the others, so I answer louder than the rest. ‘Pays, teacher.’ It’s as if we are having a private conversation about something else.

But pays, how? Everyone else at home is free and safe, but for us? Is it not bad enough that we’re stuck here ‘in the path of bullets’, as Big Head so kindly put it, do we also have to be punished with class? Just because Koma loves maths—for him its meat to chew on, does he have to force it on us? For me, it’s dry bone. Moreover, we’re all in different classes, so it’s confusing when he opens different pages of Longman’s Mathematics for East Africa, and tries to teach us all different things at the same time.

Me, I’m not afraid of Koma; I put up my hand on our first day and asked, ‘Why are we in class?’ I almost added ‘wasting time.’

‘You boy, can’t you see how lucky you are to have this extra time to revise, moreover with me?’ He spread out his arms as if to show off his muscles: ‘All the others are at home sleeping! No pain, no what?’

Lucky? Sure, like, if we lied to ourselves enough, we’d believe it; it would become true. Teachers! They have this thing of thinking we’re foolish enough to believe what they say. Like how, in Civics class last term, the teacher droned on about how the police protect us. Really? Even a child of five knows better; he just needs to listen to the news once. We all just kept quiet and waited for the bell to ring.

Me, I can escape teachers’ lame lies by going back to old Okiror’s war stories. He’s a mzee made of nothing but wrinkled skin and bones, who sits under the huge mango tree outside St. Mark’s the whole day, back in Aboke, holding an ancient gun like a baby. He repeats stories of his glory days to us kids who hang around; adults don’t have the patience. I was mesmerized as much by the stories as by how his saliva spattered from his rubbery lips as he talked.

As Ociti and I walk from the garden, our cobs held close to our bodies, I wonder what story Koma will feed us now: that the army is fighting for us—or is it the rebels? My empty belly tells me they’re tending to their tummies, just like we’re doing now. I can almost taste the salty chewiness we will soon enjoy; I chew my inner cheeks and swallow saliva. It helps, believe me.

Just then, on our way to the kitchen, just as we pass by the dorms, there’s a bang like thunder and I bite my tongue. We fall to the ground, my mouth stinging, eyes shut tight against—what? Has the sky cracked? Silence, as though the world is taking in a deep breath. And then all the birds in the world scream and fling themselves into the sky.

‘Run!’

Ociti scrambles up and takes off ahead. Koma had said that if anything happened—not that it would, he added—we should all run to the nearest building. The birds’ shrieks are silenced by sharp sounds: TA-TA-TATATA-TA-TATATATA. Like that. On and on, from all around.

Somehow we reach and fall onto the dorm door, the others too, one after another, as Ociti fights with the handle. It opens; we pile in and scramble under the bunk beds. I trip on the doorstep, fall on my hands and knees into the room and crawl like a desperate lizard under the nearest bunk bed. Koma is already there, imagine, pulling in his long legs, trying to squeeze into a corner. I wish I could laugh: a whole teacher squashed under a bed! Tim also presses in: hot flesh, shoes, shorts, dirt, sweat. Bosco tries to join us.

‘Go to the other one,’ Koma hisses.

The poor boy has to crawl out into the open and scuttle to the next bed. We lie as still as we can, trying to quiet our panting, listening to the sharp eruptions as if they’re telling us something. The bursting noise is nothing like Mzee Okiror’s war stories, and I thought I knew guns. Right next to my face, the iron legs of the bunk bed are strong and straight like prison bars, but how can they protect us? I’m glad to be so close to Koma, I won’t lie: his long bent limbs and warm breath are more reassuring than hard metal.

Strange, but as we hide like cockroaches, as my heart hits my chest, I feel something close to relief: this was what we have been waiting for all along. Finally, it has come. Everything else has been a game of using up time: cleaning, doing maths, learning how to cook, dodging bathing, ransacking the garden, what not, and then the thing happens, and you realise it has always been there, crouching at the back of your mind like a rat. No, it has been following me around like a pesky dog, along with every thought, and I tried to slap it away, to ignore it, but now it has stood its ground and bared its teeth.

‘We won’t die,’ Koma whispers.

What a stupid, stupid thing to say. Typical. Now, all of a sudden, because he’s a teacher, he’s become a prophet? Now that he has called death out loud, won’t it come? We lie there as though stuck to the floor, listening for more. Have the shots stopped? My stomach growls.

‘Don’t move,’ Koma hisses. ‘Better safe than what?’

Like I was about to do what, tour the school? One more word and I’ll stamp my elbow into his calf, which is right up next to my crooked arm. His skin is dry, ashy. A strange feeling rises in me: I want to do like my mother would: rub his hard skin with Vaseline until it shines. Or maybe spit on my palm and use that. I push it away instead.

He shifts, but there is nowhere to go, and I smell him: sweet, like an over-ripe mango. We lie there: cramped, aching, painfully alert, listening to our breathing match for the longest twenty minutes of my whole life.

I shut my eyes and force escape to Mzee’s stories. Ask me the name of any gun: Beretta 92, AK-47, AKM, AK-74, Type 56; what hadn’t I learnt from Mzee Okiror? The deacons had tried to chase him away from outside St. Mark’s, but he was a fixture like the monster marabou storks that we screamed and threw stones at. They would squawk and swop up and away, but hover in trees nearby and soon return, landing like clumsy helicopters. Mzee Okiror would aim his rifle at one of them, his eyes so wrinkled they seemed shut, gun trembling in gnarled hands. We waited, holding onto each other.

‘Aaaah! They’re just birds—me, I kill people!’ and he stretched open his mouth with silent laughter, exposing rosy gaps, saliva dribbling, as he beat his skinny thigh.

Every single time we waited breathlessly for the shot, and every time, somehow, he fooled us, and we stamped our feet, annoyed. ‘You mzee! We shall report you.’

Old Okiror made up for this by letting us watch as he opened his gun lovingly and polished it, rub, rub, rubbing each section with a dark oily cloth, holding it delicately close like an injured child. It seemed alive to me, like the metal breathed, even as it could stop breath. I remained by Mzee’s side for hours in the idle holiday afternoons, long after the other boys had got bored and run off. Mzee had stories! It seems he had fought in every army: one day he would say he was with the African Rifles of World War II, fighting for the British in Burma, wherever that was; then next the colonial army had to ‘pacify’ the Karamajong—he said the word in English, explaining, ‘you know them; they never want to be ruled by anybody, let alone whites.’ That’s when he came back with lots of cows and got his first wife. Then the next time he said he took part in the attack on the Buganda King’s Palace in Kampala in 1966; then later he volunteered with the SPLA in Sudan in the 1980s and even later trained the UNLA to fight the NRA. When I told my mother, breathless, counting the armies on my fingers, she chewed her teeth. ‘What a bunch of lies! That mzee was in Amin’s army and survived it with nothing, not even his teeth. Do you think he has a brain left?’

But he had; I knew this ‘coz he knew the names of many many guns, and he drew them for me at the back of my exercise book even though his fingers couldn’t really bend properly. His fingers were as stiff and as hard as metal and were the same grey-black colour as if the gun itself had seeped into his fingers. Eh, but when my mother saw the pictures, the way she tore out the pages, spoiling my exercise book! Chewing her teeth juicily, she tore them into tiny little pieces, opened her palms and let pieces flutter to the ground, her eyes hard on me.

‘You want to be like him, proud of having done nothing but fight other people’s wars? You want to end up like him, with nothing but stories? Rubbish!’

I couldn’t answer her back, of course. But wasn’t she the one who always said respect the elderly? And at least he had been all around the world and back, so why couldn’t he tell all those stories, why not?

What is that? A rustling, a rush like wind, louder, louder. Rain? Sounds like the steady clomp of a herd of cattle pushed to a jog fill everywhere; closer, louder, a stampede—of what? Wild animals? But from where? There’s no forest nearby—

I can’t stop myself, I have to see. I crawl out from under the bed. Koma grabs my foot, but his warm hand is slippery with sweat, and I twist out of it, creep up to the window, and slowly pull myself up to my knees.

‘Get down, you!’ Koma hisses, for once talking sense.

But the thunder calls me: I inch my head up, up, until my eyes are just above the window ledge, my fingers grasp it tight. A tremendous mass of blackness moves hugely across my eyes: Men jog forward as one, black all over: oily shiny chests and arms, black shorts, glowing arms swinging, coming from behind the classroom block, moving across the compound, towards our dorm windows and then onwards, disappearing round the building.

‘Whaaaat?’ My voice a scratch.

Ociti’s face comes up beside me.

‘You stupid boys, I said get down!’

I cannot take my eyes off the … this gigantic swarm of black bees, no, more like a monstrous shiny-black centipede with a hundred legs. The men stare straight ahead, all of them. Light seems to bounce off their shiny chests, making them hazy like a thought you can’t quite grasp.

After a long thudding instant, they are gone. And that’s when I know; spirits, of course. Ociti and I slip down from the window, slump to the floor, and stare at each other blankly.

The thunder recedes, becomes an echo of itself, far off rustling, a reverberation, and then, incredibly, nothing. It’s as if the spirits have sucked up all sound and left us in stillness like the first day ever. From above us streams a simple, astonishing afternoon light. Have I ever noticed it?

Snuffling, small heaves, some boy under the other bunk is crying. Tim. I can’t even laugh at him. The room grows smaller, as the smell of urine and fright and sweat and light too bright to hide in expands and throbs, and all of us boys, and Koma too, hate to be so close and want to be closer.

An old memory rises of the biggest thing I had ever seen when I was four: a yellow monster as big as a house, with one giant, iron-grey chain wheel. Oh, how it roared, and how its huge rolling foot flattened everything it passed over, and how we kids cried because the devil itself had come to destroy our village! The caterpillar had come to Aboke to bring us a tarmac road. When we got used to it, how we ran around it, screaming and laughing! And how we were beaten for playing near it. And oh, when it rolled away weeks later, leaving a wide black sticky road as if leading to heaven, how empty a silence it left.

‘Lakwena rebels.’ Ociti’s voice is high and slippery.

So that’s them? The powerful, magical, spirit-possessed army? So the rumours are real? Who doesn’t know the stories: the barren witch-priest with one breast, the red fire that flies out of her eyes, the bullets that bounce off them, the stones they turn into grenades, the magic oil that shields them, the rivers they walk over, all that?

‘They look like how?’ Bosco squeaks as he pokes his head out.

‘Shut up, boys!’ Koma’s voice no longer booms; part of the upside-down world.

‘Black, black … black,’ I whisper too, rubbing my eyes. I turn to Ociti. ‘You saw?’ Already, I’m beginning to doubt my own eyes and ears.

He nods, says nothing. Then I notice water, or something, trickling from Ociti’s splayed out legs. I push him, but he is glued to the growing puddle. I shift away and we watch the pee crawl slowly towards the door, glistening with sunlight.

Finally, birds start calling, questioning. Koma creeps out from under the bed, and unwraps his long body, straightens, stretches, raises his arms high, as if he too is working some magic: becoming himself again: a teacher, a man. I watch from below, wanting to believe in him. With breath and doubt and whispering, we start rising too.

‘Ssshh. First wait. Fortune favours the what? … No, not that one.’ Koma’s low, soft voice is oddly reassuring.

He shakes out his long slightly-bowed legs and I want to wrap myself around them. As the birds continue, so sweet and normal, he walks towards the door, upright, chest open like a hero, opens it, takes that step that tripped me, out into the brilliant light, and into a loud clap, and a shriek from somewhere. The heavy thump and clumsy shape of his fall will repeat itself behind my closed eyes for years. I can see him clearly through the open door, in light that has no shame, writhing on the ground like Auntie Joyce when a pastor from Nigeria came to St. Mark’s and shouted angrily at her swollen legs and feet, and she fell to the floor and squirmed like a fat but overwhelmed maggot. Blood spurts out of his mouth, a faulty tap, and he goes still. I wait for him to get up, dazed and sluggish like Auntie Joyce did.

I press my head hard into the cold floor and feel my thighs and shorts soaked in warm wetness. I close my eyes but nothing stops.

Heavy footsteps. Kiswahili back and forth, and a shoving and dragging of something heavy across the ground. The thud of boots is on the veranda, and door after dorm door is flung open. Ours, already open, is pushed, hits the wall, swings back and is held. Why did we bother to hide?

‘Get out!’ As sharp as that shot. ‘Are you deaf?’

Ociti is the first to crawl out, slowly, staying as close as he can to the floor.

‘All of you! Outside.’

We do, like grovelling dogs.

‘Kneel there. Hands high. My God, you stink!’

We shuffle as close as possible ‘till our bodies touch; a mess of tears, pee, sniffling. We are kneeling before Koma.

‘These are school boys, just,’ one camouflage-covered figure says to another.

Their boots are caked with mud. I can’t dare look up, not even to peek at their guns.

‘Where are the others? … I’m asking, are there others around here?’

We shake our heads.

‘What’s wrong with you; can’t you talk?’ One of them, short and thick, nudges Bosco, at the end of our wretched row, with his boot. ‘How come only you are here?’

‘They left us,’ Bosco squeaks and then begins to cry for real. I peek sideways at him. He can’t bring down his hands to wipe the streaks of tears and phlegm from his face. ‘Boys don’t what?’ Koma should say.

‘Stop it, you stupid boy! Useless!’ The soldier laughs.

The two stride away, holding the straps of their guns firmly like handbags. Mzee Okiror’s gravelly voice reminds me helpfully: AK-74.

The sun stares at us, unrelenting like we’re guilty. My knees become stabs of pain, my arms too, but I dare not shift. Sweat stings my eyes, but when I close them, I feel dizzy.

Soldiers come up in small groups of two or three until they are about fifteen gathered the other side of Koma, who looks like he fell down dead drunk in red puddles. Here come the flies with a cheerful buzzing. One of the soldiers takes a black box out of his pocket and shouts into it. A kind of radio he can talk into? Old Okorir hadn’t talked about that. After listening, nodding, barking back, he beckons the rest. ‘We meet at the market,’ Captain says. They nod, gather themselves, fling us leftover looks and stride off.

The short one who first talked to us turns and comes back. ‘Your teacher?’ He points at Koma with his gun. We nod. He shrugs. ‘Find a way to bury him. You boys are lucky you didn’t follow him out. Listen; don’t even think of leaving this compound. Don’t move, move around, you hear? The Lakwenas are nearby if you don’t know, and they have no mercy. No mercy at all. They eat boys like you.’ He shakes his gun at us and then jogs off to catch up with the rest.

Again, like the Lakwenas, the soldiers are here, and then they are not, like magic. Then why are we kneeling here, and why is Koma lying over there? The front of his shirt has turned maroon. He is not flicking off the flies that play on his face. Those lips are open, slack.

Eventually, as always, the birds start their chirping and singing again. When the sun forgives us a little, and an evening breeze starts to chill our clammy shirts and shorts, Bosco moves, and we follow him, shuffling back into our room, and creeping back under the bunks. The now shadowy smothering space is damp and familiar, and our warm smelly bodies, a comfort.

I close my eyes and see those flies on Koma’s face, his eyes and mouth. What would he say? He makes no sense most of the time, but that doesn’t mean flies should just sit on his face. His warm body should be here, filling up all this space. He calls me, I swear, and I have no choice, just like when I rose to the window, no choice but to believe that old Okiror would shoot: I crawl out from under the bunk again. Trembling like I have malaria, I tug a blanket off a bed, move forward on all fours, open the door, go down that dreaded step and out across the grass, my knees stinging all the way. The sun is weak now. I reach Koma, and the flies rise in unison. I wave them away with the blanket and they buzz angrily. For some reason, I want to touch his legs, and I pull them as straight as I can. They are as heavy as I imagined; they are still warm, his arms too. He doesn’t say anything as I lay the blanket over him. I should go back inside, leave him alone, but I shuffle around him, my knees sinking into the soft wet ground as I tuck in the blanket edges under him, while the flies hover above.

2. The Street Sweep

Meron Hadero

Originally published in ZYZZYVA 2018

Getu stood in front of his mirror struggling to perfect a Windsor knot. He pulled the thick end of his tie through the loop, but the knot unraveled in his hands. He tried again, and again he failed. Did he really need the tie? He guessed it would probably be easier to convince the guards at the Sheraton to let him in with one. And even then….

But he couldn’t work out the steps, so Getu put the necktie in his pocket and decided to try his luck without it. Sitting at the edge of his mattress, Getu waited for the hour to pass (he didn’t want to arrive too early, too eager). His mattress was on the floor in the corner, and it was covered with all of his clothes, which earlier that evening he had tried on, considered, ruled out, reconsidered, tossed aside before choosing a blue shirt (stained under the arms, but he’d conceal the stains with his jacket) and black pants. Until that day, Getu thought this was an adequate wardrobe, fairly nice for a street sweeper, but he had noticed even his best pants were worn at the hem, so he brought them to his mother.

She was busy chopping onions, and her red hands and tearful eyes gave Getu pause. He didn’t want to add to her burden, but he needed her help. ‘Momma,’ he said, and she immediately responded, ‘Later,’ and walked right passed him to the garden to pick some hot peppers.

He thumbed the rebellious threads that seemed to be disintegrating in his fingers. ‘Please, Momma. This stitching is coming apart.’ She didn’t look up from her vegetable garden, so he pressed on. ‘I need to look nice for Mr. Jeff’s farewell party.’

‘Ah, Mr. Jeff,’ she turned to face Getu and would have thrown up her hands except for the peppers resting on her lifted apron. ‘Again with Mr. Jeff,’ she groaned.

‘I have to see him. It’s his last night in Addis Ababa, and he’s been so good to me,’ Getu explained, following his mother back to the kitchen.

She called over her shoulder, ‘Has he been good to you? What has Mr. Jeff actually done for you?’

Getu hesitated, then said, ‘Mr. Jeff told me he has something for me.’ He’d have said more but she was barely paying attention to him, focused on wiping the peppers off on her apron, splitting them in half, and taking out all the seeds. ‘Momma,’ he said.

‘I heard you, it’s just what is it you imagine he has for you?’ Getu didn’t dare honestly answer that question, his mother’s ridicule primed for the slightest provocation. Ever since Jeff Johnson invited him to the party, Getu couldn’t stop himself from guessing what this something might be. Over their months of friendship, Jeff Johnson had told Getu how important Getu was to him, how his organization could use a young man like Getu, and what a brilliant, keen head Getu had on his shoulders. Getu’s hopes had soared as he pictured the good job he’d surely be offered. In this moment, he nearly told his mother all about the new, stable life he’d imagined, the freedom from worry that would come from the big paycheck he’d surely bring in, which would be so liberating now that the government seizure of land was creeping closer neighborhood by neighborhood. Even the Tedlu’s had lost their home just a month ago, and they only lived five blocks away. But Getu simply replied, ‘I just want to say goodbye to Mr. Jeff.’

‘Getu, if this Mr. Jeff really wants you at his party, then he won’t care what you wear.’

‘But Momma, it’s at the Sheraton,’ Getu whispered.

‘At the Sheraton, did you say?’ She turned and stared at him with raised eyebrows and a sorry look in her eyes. ‘It’s at the Sheraton?’ Her tone started high, then fell with Getu’s spirits.

‘Do you really think this man wants you there? At the Sheraton? He invited you to a party at the Sheraton? Only a man who has spent every day here having his shoes licked and every door flung open would be so unaware as to invite a boy like you to the Sheraton. To the Sheraton! Who is this Mr. Jeff?’

Getu didn’t have the courage to reply, so she continued. ‘Let me tell you. He comes, is chauffeured to one international office after another, and at the end of the night, he goes to the fancy clubs on Bole Road, feasts, drinks, passes out, wakes up, then calls his chauffer who has slept lightly with his phone placed right by his head and with the ringer turned up high so as not to miss a call from the likes of Mr. Jeff and disappoint the likes of Mr. Jeff. And then one day this Mr. Jeff invites my boy to a party at the Sheraton. At the Sheraton! They’ll never let you in of course. The Sheraton? Oh, I could go on about this Mr. Jeff.’

Getu’s mother had long ago formed her opinion about the Mr. Jeffs of the world. She had seen men and women like Jeff Johnson breeze through the country for decades, an old pattern. She’d kept her distance from these eager aid workers flown over for short stints with some big new NGO, this or that agency, such and such from who knew where. They appeared in her neighborhood, gave her surveys to fill out, and offered things she reluctantly accepted (vaccines and vitamins), things she quite happily pawned (English language books and warm clothing), and things at which she turned up her nose (genetically modified seeds and mosquito repellant). Without fail, the Mr. Jeffs shaped then reshaped her neighborhood in new ways year in, year out. She compared them to the floods that washed out the roads in the south of the country each rainy season carving new paths behind them, a cyclical force of change and re-creation. Each September after the rainy season ended and the new recruits from Western universities came to Ethiopia, she was known to have said, ‘And now let the storms begin.’

‘Momma,’ Getu said softly snapping his mother out of her thoughts. ‘This is a really important night for me.’

‘I know you think that. But you’re eighteen, and you haven’t seen enough yet to know what I know.’

‘Eighteen here is like seventy-five anywhere else,’ he rebutted.

‘Can’t I talk sense into you? Is a mother’s love and wisdom no match for whatever hold Mr. Jeff has over you?’

‘But Momma, we need him. He’ll help us save our home,’ Getu said, finally owning up to that hope that had started as a little seed and sprouted and taken root and now seemed as sturdy as an oak.

After a pause that would have been enough for her to turn the idea around in her head more than once, she asked, ‘Do you think he can do that?’ She didn’t believe in the Mr. Jeffs, who seemed predictable by now, but she knew Getu was full of surprises.

Getu held out the clothes he needed mended, and she took them cautiously. Getu followed her to the living room and watched her sew expertly. As she moved the needle through the thin fabric, she flicked her wrist, and mumbled the long list of chores she was putting on hold to take care of this task. Getu found his mood lifting as he saw her expertise with the needle and thread. His clothes looked almost new. When she’d finished, Getu took them gratefully from her, though he felt her resistance still, for she held her tight grip even as he pulled them away.

Anyone could see the Sheraton was palatial, literally seemed ten-times bigger than the presidential palace, and there were several reasons why. Of course there was the size; the Sheraton was sprawling. Also, the presidential palace was gated and tucked into a forested acreage in the city, so the structure peeked out from between the iron fencing and shrubbery. It was impossible to behold. But you could behold the Sheraton looming above all else on a hill in the city center. At night, it was spotlit from below, and with the neighborhoods around it empty or without electricity because of frequent power shortages, the Sheraton, alone with its invisible generators, illuminated that part of town each night, every night, no fail. Most importantly, the Sheraton was exclusive but not exclusionary. Some were allowed in while others were not, and this selective accessibility gave it more mystique than the palace, which was completely off limits to all but the president and his close coterie. The Sheraton created a sense of hope when it opened its arms to the few, and so occupied the ambitions of many. Inside, there were cafés, restaurants, a sprawling pool, and enough amenities to fill a hefty fold-out brochure, including a multi-DJ nightclub called the Gaslight. The Sheraton was an unmistakable presence in this city, an isle of exclusive luxury that didn’t quite touch down.

Walking the long road from his home to the Sheraton, Getu carried his jacket, tie in pocket. He walked slowly so as not to get too sweaty by the time he arrived, and he walked, he practiced all the ways he’d ask Mr. Jeff for his job, his just reward. As soon as he had the courage, he’d gently bring up the matter of the job he felt was due to him. As he made his way through town, he passed burdened mules, cars trapped in traffic jams, old men and women who preferred trudging along the road to waiting for the crowded buses. Young men sat on street curb getting stoned on chat, which they languidly chewed with nothing better to do than watch the slow moving yet frenetic scenes drift by.

When Getu approached the foot of the hill that led up to the Sheraton, the buzz of the city quieted. Around this barren land, bureaucrats had erected yellow and green fences of corrugated tin to keep out any unwanted men, women, dogs, cats, and others they considered strays. It started with a single law: if a house in Addis Ababa is less than four stories tall, then your land can and will be seized. To keep your home, build! Whether there were new investors lined up or not, land across Addis Ababa was being exuberantly razed to make way for the new. Neighborhood by neighborhood, stucco houses vanished; make-shift tent homes made of cloth and rags and wood were swept away; moon-houses put up at night by leaning tin siding against a wall were tossed aside by morning.

‘Who has a four-story house?’ Getu’s mother had shouted frantically when she first heard about the law. ‘All these powers that be will get rid of everything, except maybe the Sheraton,’ she had said.

Getu said, ‘Be calm, I’ll take care of it. We’ll make it work.’

‘What will we do? Of course we’ll move wherever they put us. I hear they’re pushing people to the outskirts of town, but how will I get to work then? I was born in this house, and why don’t they just leave me alone to die here, too?’

‘I’m going to handle it, Momma. You’ll see. I’ll make you proud,’ Getu said, stepping close to his mother and rubbing her back.

‘Lord, this son of mine,’ Getu’s mother said into her folded hands.

‘There’s a way,’ Getu responded. ‘I can get a new job,’ Getu assured.

‘You sweep sidewalks. What could you do with your broom and your dustbin? Anyway, who’s to say that today they tell us to build a four-story house, tomorrow they won’t demand the Taj Mahal. Just let it go.’

‘But, Momma—’

‘What did I do to end up with a dreamer for a son?’

‘I could get a job with one of the international organizations. We could build a dozen four-story houses.’

‘What food did I let cross my lips—didn’t I forgo meat and dairy each holiday when I was pregnant? Didn’t I pray enough? Every week, did I not attend church?’

‘Mother, you don’t understand. I have a new friend.’

‘Did I stare too long at someone cursed with an evil eye?’

‘I’ve helped him. He’ll help me when the time comes. Mr. Jeff is a friend of mine.’

Up through the swept-clean land, up the hill, along the winding road, Getu walked to the Sheraton and, before he was in the sight-line of the guards, put on his jacket, and smoothed his shirt, the necktie still in a bundle in his right-hand pocket. Getu also brought a small wrapped gift, a map of the city that he bought at a tourist shop in Mercato. Getu circled where his house was on this map, and on the back he wrote his address and phone number should Mr. Jeff want to visit.

Though the sun hadn’t set yet, the spotlights in front of the Sheraton were already on, illuminating the driveways and pathways outside the hotel, every inch meticulously landscaped with palms, hedges, and blooming flowers punctuating the long curving roads that all led to the five-story building and its various wings and annexes. Getu took a deep breath, and stared at the vast space. He tried to visualize walking up to the guard, throwing a casual smile, saying a quick, ‘Hello, how are you?’ Maybe he’d affect an accent so the guards might mistake him for one of the diaspora who lived abroad and returned with foreign wealth and connections and ease, it seemed.

He took his first step down the hotel pathway. The cement beneath his feet was spotless, as if it had just been scrubbed clean. ‘Remarkable. They even kept out the soot and the dust,’ Getu said to himself.

When he reached the guard stand, Getu mumbled a greeting to the two guards. One of the guards, the short one, walked up to Getu, and the other, quite tall, stepped back and began to read the paper. The guard in front of Getu was dressed in a khaki-colored suit, and wore a black top hat with gold braided trim. He casually flung his weapon over his shoulder, then looked around Getu, to his left, his right, almost through him, it seemed. ‘Are you here alone?’ the guard asked.

‘Yes, I’m here to meet my friend Mr. Jeff for his going away party.’ Getu tried to hold himself tall. ‘He invited me.’

‘A party, huh? Here?’ The guard swayed onto his tip-toes and tilted his head back, and so managed to look down on Getu, despite being a couple inches shorter than him. ‘Where are you from?’

‘I’m from Lideta. I have cousins in America, so that explains my accent.’ He was from Lideta, a small, modest neighborhood that rested in the shadow of the Lideta Cathedral. The rest was lies.

‘You call him Mr. Jeff?’ The guard considered this. ‘Are you his servant?’

Getu shook his head. He wasn’t convincing them. He’d have to think fast, and fiddled with the necktie in his pocket. If only he had stopped along the way to get help putting it on… ‘I am, as Mr. Jeff says, his man on the street, his ear to the ground. I help with his work.’

‘What kind of work?’ As the guard walked around Getu, his heels clicked rhythmically against the ground like a ticking watch.

‘NGO work,’ Getu said, and seeing the guard’s eyebrows rise, he kept on. ‘International NGO work,’ Getu stressed. He had the guard’s attention.

The guard looked Getu up and down closer than before: Getu’s worn clothes, his short rough fingernails, the quality of the calluses on his hands, the tan lines at his wrists, the red highlights in his hair, his muscular form, the freckles on his cheeks, the cracked skin of his lips. ‘What do you do for him? A farmer, maybe? A herder? Are you his laborer?’

This was taking a turn for the worse, and Getu scrambled to get back on course. ‘I help my uncles in the countryside a few times a year. A man who is at ease in the city and the countryside, Mr. Jeff says. I’m his versatile aide, Mr. Jeff calls it.’

‘But what do you do?’

‘He asks me questions about local things, and I answer them.’

‘Does it pay well?’ The guard’s skepticism mingled with blossoming interest.

‘It will. He says I’m important. The exact English word is “invaluable.”’

‘Valuable?’

‘‘In-valuable,’ Getu corrected, thinking of how to steer the conversation back to those big closed doors.’

‘But why you, why are you in-valuable? You don’t look like you went to Lycee or the British school?’

He wished the guard would stop inspecting his clothes like this, like they were his calling card. If only he’d had another way to identify himself. ‘Just think of me as a scholar. I mean, schooling-wise, I’m mostly self-taught, but I was accepted to American university. The fellowship wouldn’t cover all the expenses, but this impressed Mr. Jeff enough when I told him.’

‘That can’t be true.’

‘It is,’ Getu said. And it was. Getu was still staring impatiently now at the door of the Sheraton, held open for what he guessed was a French family, and he talked faster. ‘My mother says it’s like a disease, but I’ll read anything. Math, science, history, literature, law, politics. And I remember it, too. Mr. Jeff says it’s a near-miracle.’

‘Yeah right,’ the short guard said, looking over his shoulder and taking the day’s paper out of his partner’s hands.

‘You read English, of course,’ he said to Getu sarcastically.

‘Of course,’ Getu said back. ‘English, French, Amharic, German–’

The guard put his hand up. ‘Just read this first paragraph.’ He pointed to the story on the top left side of the paper, then watched as Getu read. A few seconds later, the guard snatched back the paper. His weapon slipped a little, and the guard hoisted it back over his shoulder, his attention fixed on Getu’s eyes. ‘What did it say?’

Getu recited word for word a caption about the last term of the first Black president of the U.S. and a story about the new round of World Bank loans. ‘That can’t be!’ The tall guard came closer to see what was going on.

‘This boy’s like Solomon, watch,’ said the short guard as he put the paper back in front of Getu. ‘Read this paragraph,’ he ordered.

Without needing to be told, Getu read, looked away a few moments later, and recited the column about farmland rented out to foreign corporations.

‘It’s a trick,’ the tall guard said. ‘No way you memorized it just now.’

‘He works for an international NGO,’ the short guard explained.

‘Can you let me in, I need to go to my boss’s, my friend’s, Mr. Jeff’s party. It would be rude of me not to, and he is an important man.’ Getu said this impulsively, not sure if it was true.

‘What was his name? What’s your name?’ the tall guard asked.

‘My name is Getu Amare. His name is Mr. Jeff. Jeff Johnson. Jefferson Johnson to be precise. He introduced himself to me as Jeff Johnson, but out of respect….’

‘He’s with an NGO. We can let this guy in,’ said the short guard.

‘Is he on the list?’ the tall guard asked.

‘I don’t know about a list. I am Getu Amare.’

‘Wait here,’ the tall guard said, and as he turned and pulled open the tall glass doors of the hotel, a gust of cool air sent a chill down Getu’s neck while he watched the guard disappear inside.

Getu had met Jeff Johnson six months before by a bar across the street from the UN agencies. Every day at 6pm, the bar filled with aid workers, both locals and foreigners, but mostly foreigners. When Getu was sweeping the sidewalk one warm evening, Jeff Johnson and a group of other Americans stood outside smoking and talking loudly. Jeff Johnson called out to Getu and asked him to settle an old argument about the extent that ‘everyday people’ benefit from aid given to corrupt governments. The parking lot attendant heard this question, turned, and walked quietly and quickly away. The bouncer stepped inside, making a general gesture of being cold in the 70-degree weather, but Getu, who’d never had an audience like this before, spoke loudly. Jeff Johnson and his friends fell quiet, leaned in, and listened attentively to each word.