6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

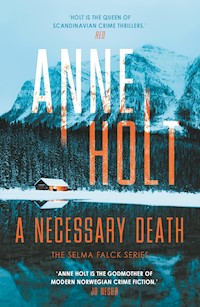

· AN INTERNATIONAL NO.1 BESTSELLER · 'Anne Holt is the godmother of modern Norwegian crime fiction.' Jo Nesbø ____________________ The snow is falling Selma Falck is living a nightmare. Trapped in a burning cabin on a freezing snow-covered mountain, she has no idea where she is or how she got there. Bruised, bleeding and naked, she barely makes it out in time as the flames engulf the cabin. With no signs of human habitation nearby, the temperature rapidly dropping, and a blizzard approaching, how will she survive? She's lost in the wilderness As Selma fights the cold, the hunger and her own wounds, she eventually forms a frightening picture of the past six months. Not only does she have to find a way to stay alive, she needs to make it back to civilization, quickly. Murder has been committed, and a great injustice must be stopped. The very future of the nation itself is at stake... If the cold doesn't kill her, they will...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR

‘Step aside, Stieg Larsson, Holt is the queen of Scandinavian crime thrillers’ Red

‘Holt writes with the command we have come to expect from the top Scandinavian writers’ The Times

‘If you haven’t heard of Anne Holt, you soon will’ Daily Mail

‘It’s easy to see why Anne Holt, the former Minister of Justice in Norway and currently its bestselling female crime writer, is rapturously received in the rest of Europe’ Guardian

‘Holt deftly marshals her perplexing narrative … clichés are resolutely seen off by the sheer energy and vitality of her writing’ Independent

‘Her peculiar blend of off-beat police procedural and social commentary makes her stories particularly Norwegian, yet also entertaining and enlightening … reads a bit like a mash-up of Stieg Larsson, Jeffery Deaver and Agatha Christie’ Daily Mirror

Also by Anne Holt

THE SELMA FALCK SERIES:

A Grave for Two

THE HANNE WILHELMSEN SERIES:

Blind Goddess

Blessed Are Those Who Thirst

Death of the Demon

The Lion’s Mouth

Dead Joker

No Echo

Beyond the Truth

1222

Offline

In Dust and Ashes

THE VIK/stubo SERIES:

Punishment

The Final Murder

Death in Oslo

Fear Not

What Dark Clouds Hide

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus,

an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Anne Holt, 2020

English translation copyright © Anne Bruce, 2020

Originally published in Norwegian as Furet/værbitt. Published by agreement with the Salomonsson Agency.

The moral right of Anne Holt to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 867 0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 853 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 855 7

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Yes, we love with fond devotion

This our land that looms

Rugged, storm-scarred o’er the ocean

With her thousand homes.

(Norwegian national anthem, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson)

It is a paradox that liberal democracy’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness: tolerance of those who wish to destroy it.

(Bård Larsen, Democracy in Trouble. Civita, 2019)

Previously, we politicians were made to pay if we did something wrong. Nowadays we’re met with malice, contempt and hate when we do the right thing.

(Minister of Justice Tryggve Mejer, A Necessary Death)

AUTUMN 2018

Selma Falck

Someone shouts.

What she hears is her own voice, but she can’t make out the words. She can’t force her eyes open and her brain is empty. Nothing but pitch-blackness, thick and sticky, or maybe soft, as if it’s stuffed with cotton wool. Cotton is a word she remembers.

She searches inside for her own name. For who she is and where she is now. Seconds, minutes, pass, it’s impossible to know how long, all she notices is that time exists. It passes. Time passes, and she is freezing, even though she is aware of the crackling of a fire.

Still in the dark, she turns her head, and through her eyelids she can make out something red and flickering. Something is burning, and she can smell it now, a whiff of scorched pinewood.

Panic strikes her, pitching up from her diaphragm. Adrenaline pumps through her body. She touches her crotch and realizes she is naked, she is shivering, something is burning, and she simply can’t open her eyes, it is just impossible.

Selma, she suddenly whispers. I am Selma Falck.

SPRING 2018

The Meeting

‘It’s time. It’s our solemn duty!’

Tryggve Mejer was the one who broke in. He ran both hands through his hair and slammed his palms on the table. The slap was muted, as if he had regretted his outburst at the very last second.

‘No,’ a voice piped up. ‘Not yet. Probably never.’

The old man sat at the end of the table. He weighed half of what he had during the war. Soon he would have put a whole century on earth behind him, and his voice was barely audible as he cleared his throat and continued: ‘This was not what we had in mind at all. This is not our battle.’

The four others around the table, three men and one woman, said nothing.

Oppressive, stuffy silence.

The old man placed his hands on the casket in front of him. His fingers were skinny, and the yellow nails scraped on the wood when he finally drew it towards him and, with an almost imperceptible sigh, lifted it on to his knee. The cedar-wood casket was scarcely bigger than a shoebox, and everyone present knew approximately what it contained. It certainly was not heavy. Nevertheless, a grimace crossed the man’s wrinkled face, as if the exertion was too much for him. The man raised his eyes again, and let them flit around the table.

At one time his eyes had been sky-blue. Now a cataract had consumed the one on the right and the entire eyeball was grey. The colour of the iris on his left eye had also faded with the years, as if most of the blue pigment had been used up. All the same, there was still strength in his gaze, and he was well aware that he was the one whose decision was final. The others seated around the highly polished table were his to command for as long as he retained the power of thought.

And he did.

Ellev Trasop was the man’s name, and he had been born on 11 November 1918.

The baby boy had arrived with the peace.

At five o’clock in the morning, as he was fighting his way out into the world in the National Hospital in Norway, a ceasefire agreement was signed in a railway carriage in the French town of Compiègne. Six hours later, at eleven minutes past eleven a.m. on the eleventh day of the eleventh month, the most dreadful war in the history of the world until then was over.

‘Peace,’ Ellev said quietly. ‘It is peace we must protect.’

‘Peace,’ Tryggve repeated, nodding his head. ‘Exactly. Peace, freedom and democracy. That is what we must ensure.’

He grabbed the edge of the table with both hands.

‘Don’t you see what’s happening, Ellev? Can’t you see that everything is falling apart? Don’t you appreciate that respect for everything that’s the very foundation of—’

‘The meeting is over,’ the old man interrupted. ‘The decision has been taken. You are the Minister of Justice, Tryggve. You, of all people, ought to know the rules we are bound by. It was not this threat that we were to vanquish. Not all … this. This is just …’

His hand waved the rest of the sentence away. At the same time, the signal caused the till-now almost invisible woman dressed in black who stood by the door to tread soundlessly across the floor towards him. With practised movements, she unlocked the brakes on his wheelchair and pushed the casket further down on Ellev’s lap.

‘You’ll hear from me by summer,’ he mumbled as he was wheeled towards the double doors leading into the detested bedroom in which he was forced to spend more and more of his time. ‘If I’m spared.’

He knew that no one could hear this final remark.

Mina Mejer Selmer

‘You really can’t go on like this.’

Dad was standing in the doorway. Mina glanced up; he looked exhausted. He raked his hand through his hair in a gesture of despair, just like when Mum was at her most unreasonable.

‘I can well understand that this has been difficult,’ he said.

Mina did not answer.

‘Ingeborg was ill, sweetheart. Extremely ill.’

‘She was exactly the same age as me, Dad.’

Crossing his arms, her father leaned his shoulder against the doorframe. He had put on weight, she noticed. His stomach was hanging over his belt, which was too tight, and his face was pale, even though the weather had been bright and sunny for the past fortnight.

There was not much sunshine inside his office, of course. Or in those black limousines. Or in the Parliament building, or on planes or in meetings. Or in bed, for that matter, into which he usually collapsed long before it had even crossed her mind to call it a night.

‘Teenagers get ill too,’ he said softly. ‘Even small children get cancer and die. Accidents happen. That’s life. Unfortunately.’

Mina ran her thumb over the display on her mobile. ‘She didn’t have cancer,’ she muttered.

‘No.’

‘Ingeborg was healthy a year ago.’

‘Yes. And then she became ill. These things happen.’

‘She was driven to death by bullies.’

His eyes narrowed. ‘Now you’re being melodramatic.’

‘You know nothing about it.’

‘Yes, I do. The police have looked into the case, and Ingeborg was not subjected to anything more serious than what every teenager in this country sadly—’

‘Ingeborg just couldn’t stand it,’ she broke in. ‘Were you the one who knew her, or what? Were you the one who had to comfort her?’

‘Yes, I knew Ingeborg. Not the way you did, of course, but she was your very best friend. Naturally I knew her. It was terribly sad that she died, but six weeks have gone by since the funeral, and you must somehow—’

‘Get over it? Get over Ingeborg, is that what you’re saying?’

She shouldn’t cry. Shouldn’t. She bowed her head and covered her eyes with one hand, quick as a flash – a magic invocation to ward off the tears. She forced a smile and looked up again.

Dad looked so worn out. Even more so than when he had come in only a few minutes ago.

He nodded his head slightly in the direction of the living room. ‘Shall we play a game? Chess? Cards?’

Mina shook her head and placed her thumb on her phone. ‘Tryggve Mejer is a traitor,’ she read aloud. ‘He’ll be first in the queue when the People …’ She glanced up. ‘They’ve started to write “people” with a capital P. As if they were a tribe or something.’

‘Give over,’ he said, taking one step inside the room. ‘You need to stop that. Put it away.’

She threw the phone down on the quilt. Her father came closer and sat down on the edge of the bed. Mina drew up her feet and clasped her hands around her knees. Her father smelled of evening time. Day-old stress, and a little of the hair gel he combed through his hair every single morning and that turned a bit rancid in the course of a working day.

‘You’re sixteen,’ he said. ‘You shouldn’t be bothering about such comments.’

‘They’re threatening to kill you.’

‘Don’t visit those websites. Don’t give a damn about them. Their bark is worse than their bite. Far worse. Tough as nails behind a keyboard, but spineless cowards the minute they’re confronted with that filth.’

‘Every day, Dad. Everywhere. All the time. And not just …’

No.

Dad should not know. He most certainly did not need to know any more. Dad was thirty-four years older than her, but sometimes she got the feeling she had to look after him all the same.

That she was actually the only one who could look after him.

‘It’s just a transition stage,’ he said quietly. ‘Humanity must get acclimatized to the internet. Your generation is going to fix it. You’re the ones who’ve grown up with all these opportunities.’

His gaze shifted from the MacBook on the desk to the iPad on the bedside table, finishing up at her mobile.

‘I trust you and your peers,’ he said in an undertone, placing a hand on her back. ‘You’ll learn the limitations. The norms. Acceptable rules will be arrived at eventually.’

Mina did not respond.

‘Come on,’ he whispered, touching her neck. ‘Let’s find something to do. And then we’ll go to bed. We have to be up early in the morning.’

‘Not me,’ Mina said.

‘Aren’t you coming? It’s the seventeenth of May! Our National Day! I’m going to make a speech at …’

Mina lifted her face and looked at him. For a long time and in total silence. If she did not give up, and held eye contact, he would give way. As he always did. The way she could always, for some reason she had never before been able to fathom, employ a lingering look to force him to nod and leave.

Dad nodded and left.

AUTUMN

The Fire

Selma Falck could now remember her own name, but it was still impossible to open her eyes.

The smell of the fire was even more acrid now.

She was still frozen, but maybe only on one side. She tried to turn over towards the source of the heat. Her entire body was aching, and she changed her mind. She had to see it first.

Her eyes had to open, but they simply refused.

She stretched her body as much as she possibly could. Raised her right arm. It lifted. She guided her hand towards one eye and forced it open between her thumb and forefinger. It was swollen and sore, but it did remain open. She repeated the procedure on the other eye.

Stared straight up. The ceiling was untreated pine. Old and yellowed, with a flickering red glow from something that must be a fireplace. Slowly she sat up, at the same time trying to ascertain whether all this terrible pain was a result of serious injury. Whether she had broken something. Or was badly burnt; the smoke from the fire was stinging her nose more and more. She sat up straight when she finally managed to turn her head. Nothing in her body seemed grievously damaged. She had just been beaten up, and felt tender and bruised, exactly like after a never-ending handball match in hell, and she failed to comprehend why she was naked.

The fire was not burning in a fireplace. The whole wall was engulfed in flames.

She was sitting in a spartanly equipped cabin, in the living room, measuring barely twenty square metres. The furnishings could not have been renewed since the sixties. Pine everywhere, and dilapidated tartan upholstery. For some reason, the windows had no curtains. On the other side, it was pitch dark. The flames licked up the wall only three metres away from her, and she leapt to her feet faster than her aches and pains would actually allow. She groaned once she was upright, staggering and unsteady, as she struggled to force her brain to take in her surroundings.

And why she was there.

That would have to wait.

In the middle of the blazing wall she could see a fireplace. A fire had burnt down to a mound of red-hot coals in the deep, open hearth. The cinders were not inside the wrought-iron grate as they should be. The entire hearth was full to the brim and a broad trail of logs, still alight, had been built out from the fireplace and along the walls on either side. The flames had caught the wall panelling and already climbed a couple of metres up the timber. When Selma raised her eyes, she realized that it would be only a matter of seconds before the ceiling was also consumed by the flames. An ice-cold pain shot up through her thighs into the small of her back when she stepped back.

Fire extinguisher, she thought.

She tottered towards the only door in the room. Although closed, it was not locked, and led out into a long, narrow hallway. It smelled of age and dust, and she had to make do with the light from the fire in the adjacent room.

No light switches. A paraffin lamp with a glass globe was suspended from the ceiling above what she assumed to be the front door, right at the end of the hallway.

The cabin had no electricity.

The thought of a fire extinguisher occurred to her again, and she felt yet another jolt of fear when she recalled that cabins without electricity also usually had no plumbed-in water.

Selma could not remember what date it was. Not even what year it was.

On the main wall to the left were two small doors and she opened the first of these. The kitchen. Tiny, with a worktop, two cupboards and a washtub perched on a stool. Immediately inside the door was a black woodstove.

Cold.

No fire extinguisher here.

The fire had begun to crackle, and the noise grew louder and louder. She ran out of the ancient kitchen to open the next door. This room was slightly larger and bunk beds took up most of the space. The lower bunk was made up; Selma thought she could make this out in the almost total darkness. The upper mattress had no bed linen. There was a cupboard behind the door, but it was empty, as she discovered when she opened it and thrust her hand inside the inky blackness.

The fire in the living room was now roaring.

It dawned on Selma that she was not going to find a fire extinguisher. On the spur of the moment, she grabbed the quilt from the bunk bed, dragged it with her and rushed back to confront the flames.

The ceiling had caught fire. The other walls too. Pungent black smoke billowed up from the stuffing on a two-seater settee near the fireplace.

It was too late. The fire could not be extinguished, at least not with a quilt. She had to get out. The moment she made up her mind, she spotted her bag, the bright yellow North Face duffle bag. Well, she had one like that, at least. She now saw that her clothes were slung over it. Holding the quilt up in front of her as a shield from the flames, she only managed to stagger a couple of steps before the wall collapsed. Cinders and heat surged towards her. Automatically, she threw off the quilt, forward, to ward off the heat that was now so intense that, unthinking, she lurched towards the hallway. At the door she turned one last time.

Her clothes were on fire. Her bag was on fire.

The whole cabin would soon be ablaze, and she was still naked.

She could not remember spotting anything useful in the kitchen, and had no time to check more closely. She tore the sheet from the bunk in the bedroom before grabbing the front door handle. Heavier than the others, it was made of brass that still felt cold to the touch.

The door did not budge.

She wrenched the metal hard, rattling it repeatedly, and suddenly the door sprang open: it had not been locked after all.

She was out.

Panting violently, she pushed her feet into a pair of enormous wellington boots she found on the stone steps and fled from the burning cabin.

Once she was at a safe distance, she wheeled around to see the little house blazing ferociously.

Outdoors, it was icy cold: night or evening or crack of dawn. A half moon, glimpsed behind scudding clouds, showed that she was completely alone.

The mountain plateau stretched out around her in every direction. She was far above the tree line, and maybe not even in Norway.

There was no light to be seen from other cabins. No diffused light from distant settlements. Only grey-black sky, the occasional star, craggy knolls, barren ridges and heather.

Her body ached all over.

Her legs and back, her stomach and arms and hands. When she tried to wrap the sheet around her and ran her fingers through her tangled hair, even her scalp felt sore and painful to touch. Selma’s teeth were chattering and she moved closer to the fire to get some heat at least. She still had no idea where she was. Her headache was almost unbearable. Her thoughts were not even spinning: her mind was quite simply dark and blank.

‘Selma Falck,’ she whispered over and over again with every step she took into the frosty heather. ‘I am Selma Falck.’

She stumbled on, zigzagging across the ground, and stopped suddenly as the flames broke through the turf roof. For a split second, a tremendous shower of sparks shed light on her surroundings.

That was when she saw it.

The car.

Selma’s red Volvo Amazon 123 GT from 1966 was parked close to the front cabin wall. The sight brought her to a sudden halt. Soot and flakes of burning timber drizzled down from the sky and it struck her that the car could burst into flames at any moment.

She had obviously driven to this godforsaken place. After all, her car was here, it had climbed high into the mountains, and so she must be able to make the journey home.

Selma broke into a run. The sheet slid from her body as she rushed on, stark naked, as fast as the pair of ancient boots that were far too big for her would allow. She stumbled, kicking off her footwear, and ran on. Yet another rumble, a small explosion, and the rest of the roof collapsed.

Selma kept running. She had to rescue the car. If she didn’t save the car, she would most likely die out here.

SPRING

The Casket

It was high summer in the middle of May.

At night, it was still only eight to ten degrees Celsius, but on this day too the temperature had soared to well over twenty degrees even before noon. From the living-room window of the old villa in Terneveien in Hasle, Tryggve Meyer could see the Oslo Fjord glittering below, behind a city that had settled down for a rest on the day after a successful, exhausting National Day. The hum of traffic on Grenseveien, usually steady and distinct even with the windows closed, was now muffled, almost absent; only now and then did a lorry rumble past and make the crystals on the huge chandelier jingle. It was the Friday between a public holiday and the weekend, a day off taken by those who were brazen enough.

Tryggve had his hands clasped behind his back. He stood with his legs apart, squinting at the bright light. In the courtyard outside, the black limousine’s chauffeur had stepped out to stand in the shade of an enormous chestnut tree. When he glanced up and caught sight of the Justice Minister, he gave a crooked smile, patted his pocket and decided against it.

‘Did the day go well?’ a voice squeaked from the wheelchair behind him. ‘Would you like some coffee?’

Tryggve turned around with a smile. ‘No, thanks. I’d prefer some Farris. And yes, the day turned out well. Apart from Mina being at the age when …’

He gave a slight shrug. Crossed to the settee of midnight-blue brocade and sat down. Ellev Trasop waved to his carer, and was immediately trundled across the room. Another wave of his skinny hand and she disappeared as surprisingly soundlessly as always. Tryggve Mejer poured some Farris mineral water from a bottle into a crystal glass before raising it with a questioning gesture towards the old man.

‘Yes, please. She’s sixteen now, isn’t she? Mina?’

‘Almost seventeen. And a sworn anti-nationalist. The celebration of our national constitution has become an abomination for her. It’s the first time since the age of two that she hasn’t worn her national costume for the occasion.’

The sunlight etched sharp geometric outlines in white against the dark interior. Tryggve screwed up his eyes as he peered at the old man who sat in the midst of the pool of light, and without asking, the Justice Minister abruptly got to his feet and returned to the large casement window. The curtains were heavy and the fabric felt almost greasy on his fingers as he drew them shut. The living room was suddenly bathed in semi-darkness, considerably more comfortable.

‘Thanks,’ Ellev Trasop said, with a sigh. ‘These carers insist on light and fresh air. I call all this airing nothing but a draught. And we old folk should beware of draughts, as you know. The sunlight nowadays wipes out what little sight I have left, into the bargain.’

A trembling hand rubbed beneath his nose, where a little droplet had been threatening to fall ever since Tryggve’s arrival.

‘Political commitment in teenagers is nearly always a good thing,’ he said. ‘No matter what. Is she still as clever?’

‘If by clever you mean clever at school, then yes. She’s taken advanced classes in Maths and English for a few years now. She plays handball, though not at a particularly high level. Dancing on Thursdays. She also has a job at weekends, clearing tables in a restaurant. I can’t fathom how she finds time for it all. But that’s how it is at that age. Can’t miss out on anything.’

‘And politics? Is she still as keen a member of the party’s youth wing?’

Tryggve refrained from answering. ‘How was your seventeenth of May?’ he asked instead.

‘Berit called in.’

‘The Major?’

‘Yes, she’s a nice girl, Berit. A very nice girl.’

‘She’s older than me. Anything else? What did you do?’

‘I’m too old now to celebrate. Too old to live, to be honest.’

Ellev sighed and seemed to shrink into his chair. His shoulders were so narrow and angular that it was no longer possible to find clothes to fit properly. At least the kind of clothes he insisted upon: immaculate white shirts with starched collars under a dark blazer for meetings and other occasions when he met people, and blue checked flannel shirts to wear at home. Both options made him resemble a wrecked scarecrow. Ellev Trasop’s clothes were clean and, judging by appearances, received excellent care, but he gave off a cloying smell all the same. Not only from his less than fresh breath. It was as if he had already started to die from the inside out. A faint smell of decay seemed to seep out through his yellow, porous skin.

‘I’m going to die,’ he said, sighing.

‘We all are.’

‘Don’t put on an act.’

‘I didn’t mean it like that.’

‘It means you’ll have to take over. And that you have promises to give me.’

Tryggve inhaled a deep breath through his mouth and let it leak out slowly through his nose.

‘We’ve talked it all over,’ he said quietly. ‘A long time ago.’

‘No, not entirely. You can’t initiate this …’ His slender claw of a hand waved in mid-air. ‘… Rugged/Storm-scarred operation of yours. You simply can’t.’

Tryggve studied the old man and said: ‘We’re living in dangerous times.’

Ellev looked up. ‘I know that,’ he replied.

His eyes were terrifying. Tryggve always tried to fix his gaze on the still functional part. It was now so lacklustre that the old man most of all resembled a Roman marble statue, with blind eyes missing an iris.

‘We are nonetheless a liberal democracy,’ Ellev continued. ‘Paradoxical, I know. The greatest strength of liberal democracy is also our greatest weakness: we have to tolerate those who wish to destroy it.’

‘Exactly. A paradox. A dilemma. That we will soon be forced to resolve.’

‘If we resolve it, we cease to exist.’

‘If we don’t resolve it, we go to the dogs.’

‘No!’

Ellev’s voice cracked in a rasping falsetto. As he began to cough, he grabbed the glass of mineral water and drank deeply and slowly. Returned his glass to the coffee table with hands that were shaking even more.

‘I’m going to die soon,’ he insisted, ‘probably in the next few days. That’s why I asked you to come.’

A grandfather clock struck three in an adjacent room. Tryggve suddenly felt a jolt of unpleasant nausea. A bouquet of lilies in a tall vase by the window exuded a sickly-sweet, heavy scent of putrid water. He swallowed audibly and opened his mouth to say something.

‘In other words, you have to take over the casket,’ the old man said, stealing a march on him. ‘And everything that goes along with that.’

‘But … you …’

‘I really think it would be better if Berit takes over. Far better. Her background is in the military and she demonstrates better judgement than you do.’

‘Better judgement? What do you know about—’

‘I know everything that’s worth knowing,’ the old man interrupted sharply. ‘But giving the casket to Berit would mean breaking a pact between your father and myself. I can’t do that. It’s sitting over there. Fetch it, please.’

Tryggve glanced across at an imposing, dark oak sideboard. The little cedar-wood casket sat on one side of it. He remained stubbornly in his seat.

‘That was the agreement,’ Ellev said, a touch more gently this time. ‘You’ve known of it since before he died.’

This was correct. Tryggve Mejer was fifty years old, and for the past twenty of these he had been aware that he would at some point or other take over this responsibility. He shared this knowledge with three other men and one woman.

No one else.

For all his adult life he had juggled the roles of politician and lawyer, father, husband and bearer of national secrets in precisely the same way as his own father had done. His existence was compartmentalized. Some of the compartments were connected: many were bright and clear, others lay closed and locked in a far corner of his soul. There was a great deal he was able to talk about, but other things he could only share with a very few. Certain secrets were his, and his alone.

Such as that for the past six months he had been looking forward to Ellev Trasop’s death.

‘Are you ill?’ he asked.

The hoarse laughter changed into a feeble coughing fit. ‘I’ve been ill since I was eighty,’ Ellev enlightened him when he recovered his breath. ‘But yes, I’m even more ill now.’

His hand tentatively tapped his chest. ‘My heart. It doesn’t want to go on. I don’t either, to be honest. You know, when my peers began to drop dead around me, it was sad. When their children began to peg out, it moved me even more deeply. I’ve no wish to go on living until it’s their grandchildren’s turn to grow old and die. Fetch the casket, please.’

Tryggve rose from his seat. He almost stumbled on the thick carpet, but managed to regain his balance. For a moment he stood in front of the sideboard staring at the box that he had never seen without the lid being closed and locked.

It was not necessary anyway. He knew what it contained. It had existed since 1948 and been opened now and again, including by his own father. No doubt some items had been removed and others added by a number of men in consecutive succession, of whom all except Ellev Trasop were now deceased.

‘Bring it here,’ Tryggve heard behind him.

He used both hands to carry the casket and set it down in front of Ellev. The old man reached out his hand. Tryggve noticed a little key and moved to take it, but Ellev closed his fingers around it, preventing him.

‘You must promise me you won’t do it.’

‘I can promise not to do anything rash. Nothing out of keeping with the remit.’

‘We weren’t established for that purpose, Tryggve.’

‘Yes, we were, we were constituted to protect democracy.’

‘In case of a possible occupation.’

‘In a sense we are already occupied.’

‘We are not.’

Tryggve Mejer calmly took the old man’s hand. He forced the fingers open, and found barely any resistance in them. Took the key. It was small and unassuming, almost like the keys for the diaries young girls wrote in when he was young himself. He stood up to his full height and tucked it inside his pocket.

‘We’re at war with lies,’ he said. ‘With evil, ignorance, unreason, smear campaigns and hatred. And we’re in the process of losing. A living democracy implies not only free debate. Someone must also be willing to take them on.’

The old man’s breathing had become laboured and shallow.

‘Increasingly, people hang back,’ Tryggve said. ‘Locally. Regionally. And most definitely at national level. Take Elisabeth Bakke, for instance. She’s not even forty, and has been involved in politics all her life. Former leader of the Young Conservatives. A Member of Parliament before she was thirty. An obvious future leader of the party. Amazingly competent. She had only one fault, Ellev. Only one. She speaks about immigration the way I do. As if immigrants are human beings. As if they actually mean something. She doesn’t stand for anything revolutionary, not for anything …’

His hand moved quickly through his hair before he leaned forward with his palm flat on the table.

‘Not even anything radical. She’s exactly as realistic as I am, and knows that we have to set boundaries. Quite literally. It’s just a matter of rhetoric. Of decency.’

‘She stepped down for family reasons,’ the old man said. ‘That’s still permitted.’

‘She stepped down because she couldn’t stand it any longer!’ Tryggve said, raising his voice. ‘She couldn’t bear the messages, the hatred. The comments on social media. Elisabeth gave up politics because she quite simply couldn’t take any more. And she’s not alone, Ellev. Sadly, she’s not alone in being unable to take any more of it. Or in losing the taste for entering politics altogether. There are local elections next year, and we can no longer persuade the best candidates to stand.’

All of a sudden he got to his feet again. This time he ran both hands through his thick hair.

‘We can’t lose the best candidates,’ he said, with a sigh. ‘A democracy needs its most capable women and men. Being a politician has always entailed hardship. It should do. You’re placed under a magnifying glass, my father said to me when I embarked on it myself. That was fine. You’re held accountable for every smallest action, he said. Inside and outside the party. That was fine too. Now, however …’

For a fleeting second, he hesitated. Cocked his head and took a deep breath before he ploughed on: ‘Now the situation is such that real misconduct has hardly any consequences. A rap on the knuckles and a fortnight’s media storm, and then things are back to normal. Those of us who still try to stand for something, to hold opinions, to stick to the occasional principle, have to wade through a morass of savagery and malice. We are losing the best people, Ellev, and that’s dangerous.’

He thrust his hands into his pockets and hovered over him so that Ellev was forced to meet his eye.

‘In the past, we politicians were made to pay if we did something wrong,’ he said. ‘Nowadays we’re met with malice, contempt and hate when we do the right thing.’

Someone knocked on the door. Without waiting for an answer, a woman in black entered, carrying a tray. ‘Tea,’ she said briskly, and superfluously, as she put down two cups, a sugar bowl and a pot of tea on the coffee table.

The two men remained silent until she picked up the tray and disappeared again.

‘Mina has given up the AUF.’

‘What?’

The old man appeared befuddled for a moment. Then he leaned forward towards the teapot.

‘Here,’ Tryggve said, beating him to it. He poured out a cup, dropped in two sugar lumps and stirred it with an engraved teaspoon.

‘What a shame,’ Ellev mumbled. ‘I had great expectations of that young girl. She could have become Prime Minister, Mina.’

Tryggve gave a guarded smile for the first time since he arrived. ‘You were the one who manipulated her into the ranks of the social democrats,’ he said. ‘But now all that’s at an end.’

‘Why?’

‘What do you think?’

He fished out his smartphone from his trouser pocket. ‘The broken climate of debate. The many hate-filled arenas. All the hatred and abuse. Her best friend took her own life a while back. Absolutely tragic. The girl was mentally ill, of course, and according to what I’ve heard, wasn’t subjected to any more than many others. But for some people that’s enough, Ellev, and it certainly doesn’t help the most sensitive among us that these …’

The tea sat untouched. Tryggve lifted the saucer and held it out to the man in the wheelchair. He grabbed it with both hands; the cup rattled and the tea sloshed over.

‘… shenanigans are allowed to continue.’ He cast a glance at the display before returning the mobile to his pocket.

‘Hatred towards individuals. Fake news. Lies and conspiracy theories. Twelve per cent of the American population still believe that Hillary Clinton is the leader of a murderous group of paedophiles! Even now! Some people believe … some believe that the earth is flat, Ellev!’

‘Some people have always thought that.’

‘Yes. But they haven’t had the opportunity to spread their idiocy in the same way. The conspiracy theories out there are totally out of control. They’re spreading like a plague, helped along by extremist websites that make themselves look like “online newspapers”. The comments sections there are like—’

‘I don’t know very much about that kind of thing,’ Ellev cut in, raising his teacup with a shaky hand.

No, Tryggve thought. You know nothing of this at all.

‘A liberal democracy can only survive as exactly that,’ Ellev said, lowering his cup. ‘To intervene, taking action against opinions, no matter how crazy they might be, would be democratic suicide. We’re meant to protect the country from the communists, Tryggve. Not from people’s strange opinions.’

‘They aren’t strange. They are downright dangerous. Mortally dangerous. And they’re approaching a critical mass. An explosive, ignorant and highly critical mass that will destroy our country. The whole of the Western world, in fact.’

The teacup was about to topple. Tryggve took careful hold of it and put it back on the table.

‘The Russians,’ Ellev muttered. ‘It was the Russians we were meant to protect ourselves from.’

‘Exactly. The Russians.’

The old man stared up at him. Another droplet now hung from his nose, and his mouth quivered.

‘The Russians are still working to destabilize other countries,’ Tryggve said, lifting the casket. ‘As they always have. Here, there and everywhere. They have destroyed the USA, possibly beyond all chance of setting everything to rights again. They’re definitely not getting the opportunity to destroy us. Not as long as I’m able to put a stop to it.’

He moved to the door, towards the hallway, and placed one hand on the doorknob before turning around.

The man in the wheelchair was his godfather. He had once been an impressive figure, at the full height of his powers. Ellev had taught him to ski and to cycle. He had been more of a father to him than his own father had been, a better support, despite the difference in their party allegiances.

Now he was nothing but a dry husk in a wheelchair.

That same night Ellev Trasop died, only six months short of his hundredth birthday.

AUTUMN

The Car

The fire was everywhere.

The flames soared over the supporting beam that held the roof ridge aloft, and that still stretched between the gable walls. It would not be long until it collapsed. The front and back walls had caved in a long time ago, each making a separate, noisy rectangular bonfire. The hearth and chimneystack stood black and threatening in the midst of it all, surrounded by a sea of fire.

Selma came to a sudden halt five metres from the car.

Burning wall panels had fallen on the bonnet. Even the huge lump of turf that now covered almost the entire car roof was ablaze. The acrid dark smoke surged towards her.

Despite all this, it would still be possible to save the car, but the heat was so intense that her body refused to go on.

She must.

She retreated further from the fire. Using both hands, with no thought for how much pain she was suffering, she uprooted icy heather from the ground. She rubbed it on her face, over her breasts, her thighs, over her whole body; it cooled her down, and the night frost wet her skin as it melted on her.

It was dry and unbearably hot before she had advanced even three metres. She grabbed the damp sheet and held it in front of her like a gigantic shield as she once again attempted to move closer to the car.

The sheet caught fire before she reached the vehicle.

She backed away, stumbling, sobbing, falling, with the heat in pursuit, searing her skin. Her mouth was sore. Her throat too, the mere effort of breathing must have singed her windpipe. She scrambled up again, half crawling, half running onwards. Not until she found herself one hundred metres from the fire and the cabin did she turn around and look back at the catastrophe.

The car was now engulfed in flames.

Selma had not heard any loud bangs. No dramatic explosion, like in films, when the petrol caught fire and the tank blew up. All she heard was creaking and crackling, and little thuds from falling firewood. The gable wall had also succumbed now and it was almost impossible to see the car.

All of a sudden, there was an almighty boom.

Selma jumped, crashing back into a large boulder. A ferocious pain shot up from the small of her back, making her scream.

It was the front windscreen cracking open, and the interior caught fire at once. Once again the smoke thickened into an almost impenetrable fog, and a few seconds later she was aware of the stench of burning plastic.

Slowly, as all the different pains decided to coalesce, making life totally intolerable, she got to her feet. Looked around. Nothing new had appeared. No people. No cars, or anything miraculous; no vehicle of any kind to bring her a sliver of hope of getting away from here.

Home.

Sagene, it dawned on her.

She lived in Sagene.

And suddenly she remembered a wedding.

SUMMER 2018

The Wedding

Selma Falck was seated beside the toilet door at her only daughter’s wedding reception.

As early as in the church, she should have realized that it was a bad move to have come. The first pew was reserved for the family and Selma arrived in good time. As she approached the people already seated there, they spread themselves out, taking only a few seconds to ensure there was no longer room for the bride’s mother.

She should have turned on her heel and gone home.

Instead, and for reasons she was later at a loss to explain, she had followed the marriage ceremony from the second-back row. She had smiled afterwards as she boarded the bus laid on to convey the reception guests to the restaurant. She had amiably refused the offer of champagne during the waiting period while the bridal couple were being photographed on the Opera House roof. She had become bloated and slightly nauseated by the alcohol-free cider, which she had nevertheless had to continue drinking because the weather was so insufferably hot. Since other guests had buttonholed her from the moment she stepped on the bus in her dark-red dress until a bell rang to summon them to the tables, she had neglected to check the table plan.

When she finally reached the huge poster at the foot of the stone staircase, she had made up her mind.

She turned around to leave as discreetly as possible. In the stream of people making their way up, this was difficult. A stranger in his sixties with far too many teeth grabbed her arm and loudly announced that he was honoured to be her escort for the evening. Selma Falck, no less, he grinned as he dragged her, quite literally and rather roughly, with him up the stairs and towards the table in the corner beside the door marked with a blue and white pictogram. He pulled out her chair – it would move only so far – and Selma no longer had any choice. Behind her back, right on the other side of the terrace, past the almost two hundred guests who were all ranked more highly than her, sat the best man and chief bridesmaid, the bride and groom and the newlyweds’ parents. Selma had been replaced by her exhusband’s new live-in partner, barely five years older than the bride herself. By now Jesso had already delivered his speech, in the interval between the starter and the fish course. Selma’s back was aching from twisting round. Eventually she gave up and fixed her gaze on the door sign.

Not a breath of air reached the interior walls of the building.

The summer of 2018 was the hottest in living memory.

At least since 1947, declared the oldest man at the table, conjuring images of a post-war summer when fish were hauled ready-cooked out of the sea. 2018 was nothing compared to 1947, in his opinion, as he wiped the sweat from his forehead with a handkerchief so sodden that it had turned as grey as his complexion.

He was one of the lucky ones who had been invited to the wedding as early as February.

As for Selma, she had received a text message from her future son-in-law only ten days earlier:

Dear Selma Falck. If you would like to come to our wedding, I think it would be really nice. Anine too, I think. She does really. You most certainly belong at the celebrations on our big day. Best wishes from Sjalg Petterson.

It had been Sjalg who had made contact. She had not heard a single word from Anine.

The guests had offered Selma warm congratulations on the occasion, remarking on her daughter’s obvious happiness; they hugged and clapped and exclaimed about the beautiful ceremony in the cathedral, the fantastic refreshments that awaited them on the terrace up here and not least the weather, this blessed, perpetual sunshine that had rolled across the entire country since early May.

Selma must be so proud, they all thought, and so incredibly happy.

She had smiled and made small talk for more than two excruciating hours. The heat was so extreme that the restaurant had run out of ice cubes long ago, and Selma was compelled to drink lukewarm Mozell, a soft drink made of apple and grape juice.

All the same, it was better than water at almost body temperature.

The man with the teeth had clearly not followed very much of the headline news in the past six months. As early as the starter, Selma could feel an unwelcome hand on her thigh. She firmly lifted it off. Seconds later, it was back again.

Selma could not take any more.

She rose from her chair, thrust her clutch bag under her right arm, smiled vaguely into thin air and made to leave. A short shriek made her wheel around.

In the days to follow, Selma would rerun the scene in her mind’s eye, image by image, slowly and carefully. Sjalg Petterson was on his feet with the speech to his bride in his hand. He let it go and clutched his throat, his chest, he grew red in the face, then blue, before turning pale and tumbling down on to his chair. He tugged at his shirt collar, his bow tie, he tore and scratched until his grip slackened and both arms fell limply to his sides. The bridegroom’s face took on a look of astonishment, his eyes became vacant, and he slumped slowly forward on to the table.

Anine let out another scream, more piercing this time, she called for a doctor, for Sjalg’s EpiPen, for the adrenaline that could save him – it should be there, as it always was. Or maybe it was somewhere else.

Her husband’s face hit the plate with a smack.

After a marriage lasting two hours and forty-nine minutes, Selma Falck’s daughter was already a widow.

Anine was no longer the only one who was screaming.

The Assignment

Four days had elapsed since the wedding, and Sjalg Petterson’s tragic death had already been cleared up. From both the descriptions provided by the many eyewitnesses and the preliminary post mortem, it was easy to conclude that the thirty-six-year-old man had died of anaphylactic shock.

He was extremely allergic to macadamia nuts.

‘We knew that, of course,’ Jesper Jørgensen said. ‘The kitchen, the cool room, the crockery, the cutlery, the terrace … everything was washed down before we moved in. Absolutely everything. Virtually sterilized! Macadamia nuts are not exactly a food item that’s difficult to avoid. I’ve hardly ever used such a nut in my entire career.’

The man flung out his arms in consternation.

Selma Falck knew that the career he was talking about had not been lengthy, though it had been considerably more successful. Jesper Jørgensen was only twenty-seven years old, but was already considered one of the indisputably best chefs in the land. Four years earlier, he had won the Bocuse d’Or, the unofficial world championships of the culinary arts, as the youngest ever winner. Since then, he had built up his restaurant Ellevilt in Dronning Eufemias gate, in the midst of the Barcode Project, with the Opera House, the angled design of Lambda, the new Munch Museum, and all the other buildings that were slowly but surely progressing into some kind of modern urban quarter of Oslo of which Selma for one found it difficult to understand very much. Already, after eleven months in business, Ellevilt had been rewarded with a Michelin star. The following year it gained two. Only the world-renowned Maemo was one notch higher with its three.

‘Christ, I really regret it,’ the young man said in dismay. ‘Of course I shouldn’t have gone along with the idea of doing the food. I wanted to be in my own kitchen, but we don’t have space for so many guests. Sjalg Petterson is a persistent guy, and he was paying fucking good money, and I …’

Once again he spread out his arms.

Jesper Jørgensen sat in an armchair in Selma Falck’s combined home and office. The apartment was not large, two rooms and a kitchen, but it was practical and ideally situated in a newly built block in Sagene. It was only a short distance to the city centre, and fairly anonymous into the bargain. On the doorbell below it said only SF, and the actual entrance door was not marked at all. In the course of the six months or so that she had lived here, the neighbourhood had nevertheless become well acquainted with her. In the first few weeks it had been tiresome dealing with all the requests for autographs and selfies, and also inquisitive questions about her rather modest abode.

But she soon got used to it. Selma Falck was happy with her circumstances.

Since she had salvaged her freedom and finances by proving a skier’s innocence of a doping charge prior to Christmas, she had burnt most of the bridges in her life. Her licence to practise law had been handed in to the appropriate authorities some time ago. Of the thirteen million she had received in ready cash for her efforts in that case, she had given her ex-husband three. A penance of sorts, in all likelihood, as by that point she owed him nothing. Most of all it had been an attempt to persuade her children to forgive her, she had to admit each time she gave it any real thought. Something she did more and more infrequently. It had not helped much either. Anine was still borderline hostile on the rare occasions when they had to be in touch. Her brother seemed completely indifferent – at the wedding Selma had seen her son Johannes for the first time in four months.

The sixty-two square metres of newly built apartment had cost almost five million and could be furnished for next to nothing. The basement parking space was included in the price. Taking into consideration that her unfortunate penchant for gambling had bankrupted her and nearly led to her imprisonment, she had soon made up her mind to put the rest of the money in the bank. A buffer for more difficult times. The account was opened at a different bank from the one she normally used. She had taken care not to learn the new account number. Both the papers for the five million kroner and the plastic card that came with the bank account were in safekeeping at Einar Falsen’s residence. He had no idea what it was for, but knew that it had to be kept secure.

If Einar was still strange and sometimes completely off his rocker, she had at least managed to persuade the former policeman indoors. The Poker Turk, Selma’s old client, housing shark and manager of a number of illegal gambling dens in Oslo, had allowed Einar to move into the run-down, smelly bedsit in Vogts gate where Selma herself had lived during a bleak Advent.

Surprisingly enough, after many years of being homeless, Einar thoroughly enjoyed having a fixed abode. He was weird, and sometimes extremely unwell. All the same, he was the only person Selma really trusted. Even the annoying cat Darius that Selma had been forced to take with her when she left her broken marriage had stayed with him in Grünerløkka. Together, the cat and the madman looked after Selma’s money, pigging out on cheese puffs and reading newspapers that Einar went around stealing at the crack of dawn, up with the lark and ready to catch a worm or two.

Now it was Selma who had a visitor.

The master chef was in despair.

‘We’ve already had cancellations,’ he complained. ‘Loads of them. People think it must be my fault. Our fault. Ellevilt’s fault, even though we weren’t even in our restaurant. Every chef’s worst nightmare is poisoning someone. And that guy, he just … dropped dead, for heaven’s sake! For some reason that I can’t fathom we had anything to do with. Because of some fucking ingredient that I’ve hardly ever used. My food is Norwegian. Macadamia is from Brazil. A bloody Christmas nut, something that …’

It was as if all the air went out of him. He slumped on the chair, deflated, and massaged his forehead. Eyes blinking, making it look as if he was struggling to stop himself from bursting into tears.

‘What does the Food Safety Authority say?’ Selma asked. ‘I assume they’ve been brought into the picture?’

‘Yes, of course. The whole place has been examined. They haven’t found any trace of nuts anywhere. Not until now, at least. They’ve been crawling all over the place. Looking into everything. Everything that was used, the plates, the serving platters, the casseroles … every last utensil. It’ll be a while until they issue a final report, not until these …’

He took a deep breath and shifted slightly in his seat.

‘… investigations. Tests. Are completed. It takes a while. But if there were macadamia nuts in that food, then it must have been only microscopic quantities. Invisible traces, I would claim.’

‘These things happen. Some people are extremely hyper-allergic. It could even have been in a room where someone ate nuts a while ago so that someone ends up terribly ill.’

‘But then he shouldn’t have been eating in a restaurant at all,’ Jesper Jørgensen snarled angrily. ‘No one can entirely and consistently monitor food. Anyway, it was incredibly idiotic that he had given that syringe, that pipe-pen or whatever it’s called …’

‘EpiPen. Adrenaline.’

‘Yes. To his best man! So that he didn’t have a bulge in his pockets in the photographs, for goodness’ sake! And his best man just stood there, like a moron, and watched the bridegroom die without lifting a finger.’

‘He was probably in shock. These things happen. What are the police saying?’

‘The police?’

The young man now had a half-taken aback, half-sceptical, frown on his forehead.

‘Why would the police have anything to do with this?’

Selma, who was sitting on the settee with a bottle of Pepsi Max in her hand, gave a slight shrug. ‘Sjalg Petterson was far from uncontroversial,’ she said.

‘Uncontro … what do you mean?’

‘You do know who he was?’

‘Some kind of celebrity? In politics, isn’t that right? I don’t follow politics. I don’t give a fuck. I’m only concerned with food.’

‘Food can be political too,’ she said with a smile. ‘And it must have been hard work avoiding all the newspaper articles about his death.’

‘Whatever. I stay away from newspapers. Especially now. With every fucking headline we lose our reputation and business.’

Now he looked most of all like a defiant teenager. He had slid forward on the chair, his thighs spread, and was fiddling with a ring on his thumb. From one sleeve of his T-shirt, a snake crept out, tattooed in winding circles all the way down to his wrist. The head, raised to strike, was terrifyingly realistic.

‘Anyway,’ Selma sighed and put down the bottle, ‘I don’t entirely understand what you want me to do about it.’

‘Help me.’

‘How?’

‘By demonstrating that neither me nor my brainchild is to blame for that guy’s death. I …’

His phone was obviously in his back pocket, and a half-smothered double ping resulted in him groping his right buttock.

‘Bloo. Dy. Hell.’

‘What is it?’

‘More cancellations. We’ll probably have to close this weekend. No point in staying open without any customers. Fuck it.’

‘This will blow over. It’ll all be forgotten in a couple of weeks.’

He stared at her as if she had suggested a spur-of-the-moment trip to the moon. ‘You understand all about marketing, I see?’ The sarcasm was reinforced by a slight roll of the eyes. He sat up straight in the chair and leaned forward.

‘No one forgets in my line of business. I’ve got two Michelin stars. I can wave goodbye to them if people continue to believe that I’m slapdash in my work. Sjalg Petterson had a serious nut allergy. It was public knowledge, according to a couple of the boys in the kitchen. He was involved in some kind of information campaign for Norway’s Asthma and Allergy Association. The boys follow these things better than me. Besides, he was so adamant about keeping himself safe. That bloody nut allergy was not only brought up every fucking time I spoke to him or his bride …’

He raised his thumb with the silver ring. ‘… it was also mentioned in all the email exchanges.’ His forefinger popped up in the air before he also lifted his middle finger. ‘And thirdly there was a warning in the contract. Written in red!’

Unruffled, Selma nodded. ‘OK. You know best, of course. But there’s little I can do. The Food Safety Authority will probably get to the bottom of it.’

‘Food Safety!’ Jesper spat out. ‘They’re going to find out all about it, yes! But if they find a single piece of damn macadamia nut in that kitchen or any of the food, then I’m seriously fucked. Seriously! The Food Safety Authority doesn’t give a shit for Ellevilt. Or for me. Anyway, I’m the one who carries the can.’