Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Papillote Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

Grittier than TV's 'A Death in Paradise', this crime novel is set in the rural Caribbean (St Lucia) where traditional allegiances and a moribund criminal justice system provide a backdrop to the rape and murder of a young girl. When her father is accused of the crime, her brother joins the police to try and clear their father's name. While the suspect languishes in jail on remand, the young detective makes some alarming discoveries. Thwarted by his mother but supported by his girlfriend, a horrible truth finally emerges.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 287

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published by Papillote Press 2022 in Great Britain

© Mac Donald Dixon 2022

The moral right of Mac Donald Dixon to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designer and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

This is a work of fiction. Unless otherwise indicated, all the names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents in this book are either the product of the author's imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

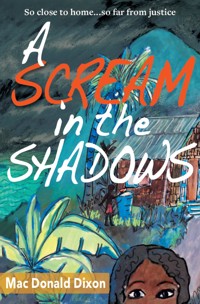

Cover art by Marie Frederick

Book design by Andy Dark

Typeset in Minion

ISBN: 978-1-8380415-3-3

ePub ISBN: 978-1-8380415-7-1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Papillote Press

23 Rozel Road

London SW4 0EY

United Kingdom.

And Trafalgar, Dominica

www.papillotepress.co.uk

In memory of all women, and men, killed in the name of love, whose souls wander the earth seeking justice.

Chapter

1

I was ten going on eleven when it happened. I remember brushing my teeth by the standpipe outside our house. It was early; I was cleaning myself for school, trying to remove bedding smells from my body and dreading the cold water that was about to fall on my skin. I hear my mother shout: “Andrew, hurry up an’ bathe; don’ forget you got school today.” When she call me Andrew, I know things serious; most times is Andy when she want me to take this for her or find that. “Yes Mama!” I shout back straining my voice; it was not clear if she heard me or not. She did the same thing every morning from Monday to Friday once I reach under the standpipe and open the tap.

That day, out of the clear blue sky a thunder come rolling in from the sea. I look out to the east over the water and catch sight of a patch of black cloud. On the hill where we live, we had a clear view of the horizon in any season. I could hear Mama talking to my little brother Marvin, but her voice break in the strong wind that always come just before the rain. Mama dispatch Laurette, my big sister, she was two years older, to her seamstress, Miss Claire, who lived on the high road (she still lives there) near our school, to lengthen her school skirt.

Laurette was growing fast, Mama say. Big for thirteen and started wearing bra after she rush past twelve. Papa always get mad when fellas by the road whistle at her, especially in her school clothes. He had put two men in court for indecent assault, but I didn’t know what that mean until I ask Mama and she confuse me with her answer: “The boys touch Laurette where they not supposed to touch her.” I was none the wiser. Laurette’s uniform was riding up above her knee and she tell Mama the boys in her class were always looking under her skirt. She bathed early, long before me and take her tea. When I went out in the yard she was putting on her clothes. I see Papa in the kitchen when I just wake up and he was still there when Mama order me outside to bathe.

Laurette pass close by me while I naked under the standpipe. She throw a little stone in joke; it knock my backside, not hard, but I pretend to bawl. I feel her hand on my shoulder as she peep over and say softly, “You getting big boy!” I bar myself with both hands and, in the corner of my eye, watch her skip off down the little dirt road and disappear past Miss Philomene’s house under the bush.

Mama send me by the seamstress later to ask if Laurette was still there. I couldn’t see any good reason why I so close to my school that I must go back home just to tell Mama I didn’t see Laurette, but if that is what Mama want, there is nothing I can do about it. I know Laurette sometimes stop and talk with Fafan when they meet in the gap. He was living at his grandmother Miss Philomene just below us. I didn’t see anything in that, but I suspect Mama was suspicious and that’s why she wanted me to report back. In fact, Miss Claire say that Laurette leave a long time ago — if I was drinking coffee it would get so cold I would have to throw it away. I reach to school just as it start, in time for prayers, let’s say a little after nine o’clock.

Looking back over the years, I know I did not see Papa when I went back to the house. The last time I saw him (I am sure of this no matter what Mama say) was after Laurette hit me on my backside with the pebble. He leave home in a hurry, down the gap towards the high road; he was always in a rush. I recall him wearing khaki short pants, but no shirt. To me he had a white plastic bottle in his hand, but I am not sure. I don’t know if it’s my imagination playing tricks. I did not see him return; I would have been at school. But Mama claim he was in the kitchen when I left the house and even now, she sticks to this. She was certain I saw Papa eating a piece of bread and taking his tea while she watch me bathe. From the angle of the bath, it’s not possible to see inside the kitchen. If I had seen him, I would remember saying goodbye to him when I leave for school but Mama does not want to hear that. In her mind, Papa was in the kitchen and never leave the house all morning until he go and help Miss Grainy cut a tree on her land above our house. Nobody can blame him for what happen outside, and I was her witness.

I find out about Laurette at school, a little before lunchtime. I was getting ready for prayers before meals, when a girl come in from the schoolyard screaming loud enough for everybody to hear: “They kill Laurette under the bush!”

The entire school down pencils and stop work. Teachers freeze at their blackboards with chalk in hand. The principal thought fast, rang the bell to bring us to order for grace although it was not quite on the hour. My eyes sweep across to where Laurette always sit in her class. She was absent. I wanted to shout out her name, but a foolish pride help me hush my mouth shut. That’s not true, that’s not true, I say to myself. I see Laurette just before I come to school; somebody playing a joke on us.

At twelve on the dot, lunchtime, school close. The undertaker had already come and park his hearse by the road. None of us remain in the schoolyard after that. They cover Laurette under a technicolour bed sheet; it was Mama’s. I could see her shape through the cloth but not her face. Mama was leaning on Miss Philomene, who was holding her up. They were walking close behind the body. Mama had Marvin on her shoulder; he was too small for school.

Papa was leaning on the bonnet of the hearse talking to the driver; his eyes were dry. I could not hear the conversation, but I remember feeling cold when he see me. There was a large crowd, people I never see before looking on and saying their piece all at the same time. I didn’t want to believe that it was my big sister under that sheet but when I get close I didn’t dare lift it to find out. Children come up and speak to me. Don’t ask me what they say. A girl offer me a piece of her bread, but I was not hungry. I didn’t spend much time by the road but I remember going back to the schoolyard after I see my father and sit down under a tall guava tree that the children did not give a chance to bear ripe guavas and cry my head off, although I was not sure for what.

After school, I race home. When I finally get a chance to ask Mama what happen, she did not answer me straight. My mind strike a blank wall and everything inside it walked out of my head. When my father come home late that afternoon lamps were lit already. Mama said earlier, when I asked for him, that he take some fresh clothes and go with the hearse to Castries. It was so confusing; I cannot remember if I peed at all for the day.

Another thing I will never forget is that afternoon sitting by the table in the kitchen. Papa was not there; Mama just finish washing some glasses; people were coming to the house later. She was about to send me to Mr Paulinos for him to fill a white plastic gallon bottle with strong rum for her. His shop was lower down the high road on the same side as our gap. Mama was searching up and down for the bottle she always keep under the kitchen table. I tell her I saw Papa go down the road with a white plastic bottle that morning, but I also remember some days before he did mix Gramoxone in it to spray tomatoes. Mama always warning me that Gramoxone is a poison and I must never put it close to my mouth. I did not think that the white plastic bottle not being where it was supposed to be was strange, but Mama thought so and muttered loud enough for me to hear. I say to myself Papa know he mix poison in the bottle so he take it to throw away and forget to tell her.

From the very next day, with Laurette’s body at the morgue in Castries, Mama start lecturing me on what to say to the police knowing they would come with questions after digesting the autopsy report. “Children does put their mother and father in trouble, so listen to me,” she insist. “Say everything like I tell you to say it, like you say your prayers. Don’ put your own two pence ha’penny in the sauce.” Her face knot up; she was ready to put licks on me if I stutter. Mama begin sowing seeds in my mind, wild seeds, making me believe they were facts. She said they going to ask you the same questions until you get tired hearing them. “You must repeat the same answer each time, or else, you will trap yourself.”

Why the police want to trap me? I had no knowledge of the law; my mind is not fully open up to life as yet. What does Mama mean? What did I do for me to trap myself? I’m not a bird that don’t know glue. How she expect me to set a trap and get catch in it — with what? I was still a child, innocent and stupid when this thing happen. What they tell me to say I say and that made my mother happy.

I cannot change my statement now, even if I want to, and that’s part of my problem with the system. Once you lie, you stick with it forever. If I say I want to correct my statement now that I know better, some smart lawyer will jump all over me and make a jury believe I am a liar. I don’t know if what I said then help Papa and his case; it certainly does not look so to me. Things that did not have colour once — frying fish in oil without flour — start getting brown in their jackets, making me wonder why I couldn’t see them like that before. Things I paid no mind to suddenly take on shapes, worms turn to butterflies, and mongoose make friends with fer-de-lance.

I can see Papa, boldface, trying to show me how he is so holy and innocent that a priest will give him communion without confession. After Laurette’s death, he could not look at me or Mama in the eyes; it’s something I never forget. Sometimes, I dream about him and I’m afraid to repeat what I see. Things come to me so real in my dreams I can touch them, and I could swear they always there. I feel afraid talking to myself and writing this down. When I mention my sister, my skin grow scales.

To me, then, it was a mystery how Laurette just stay so and die without falling sick though I hear at school that somebody kill her. The way Mama behave, I thought there was something more to it than just killing. Something I could not easily explain. Whatever it was seem bigger than me. It could have to do with the fight between God and the devil, which I been hearing about from the time I know myself. In the country, you learn to be more afraid of the dead than the living, and everything else you cannot understand is larger than life. For a long time, I believe Laurette’s death had to do with evil spirits that roam about under the bush. Mama never fail to warn us be careful of strange sounds. “Not all the noise you hear during the day come from birds,” she would say. “When you hear things you don’ understand, go about your business as if you don’ hear them.”

At school, the children were whispering among themselves: “We know who kill Laurette! We know who kill Laurette!” When I tackle them, they afraid to tell me so I involve Mama. She shake her head and start crying. “Yes, maybe they know more than police; police don’ know yet who do it.”

“For what they kill her, Mama? Why the children saying they know who kill her?” She fly into a rage and demand I stop questioning her right away. “You not a lawyer. Wait when your time come to answer questions you don’ go an’ tell the police any stupidness an’ put your father in trouble, ou tann, bon.” Mama move between her own brand of English and Kwéyòl whenever she get vex and I inherit the habit from listening to her.

It don’t matter how much I try hard to imagine Laurette was still alive, from the minute I see them push the stretcher into the back of the hearse, I know — only dead people go into the back of a hearse flat on their back. When it got closer to the funeral and the police release the corpse for burial, Mama break the news in her own strange way. One minute she looking at me, her mind far, and next, without looking, only her lips move to say, “We not going to be able to talk to Laurette again for a long time, but we will get a chance to see her before they plant her in the ground for good.”

“When, Mama? Where?” I ask. Right away she start to cry again.

“She on the fridge in Castries, Lovence go an’ see her already.”

“Why Papa go without us?” I was curious. He knew all of us were anxious to see Laurette again so I couldn’t understand why he would choose to go by himself.

“You don’ ask big people their business!” Mama shout and shut me up with a slap.

Several days go by, each one taking longer to leave than the last, but news of Laurette’s death refuse to get stale. It was the only hot rumour in Bwa Nèf and beyond. At the time, Bwa Nèf was a sleepy village on a hillside overlooking the sea on the east coast. The main road pass through it winding up hill like a corkscrew until you reach Tèt Chimen. Lower down, a narrow side road take you to the church and cemetery with the presbytery and schoolhouse nearby. The little wooden houses with their galvanise roofs, some older ones with shingles, pop up between the bushes every hundred yards or so on either side. There had never been anything as serious as a murder at Bwa Nèf and the people were afraid of police. They did not want them coming to their village and start locking them up on suspicion, like they hear happening in other parts of the island where poor people live.

People travel from as far away as Dennery village to come and see where Laurette’s body was found and ask questions. Everybody say it was impossible to find her that quick except if you know where to look. They assume, ‘Only the person who kill her would know where they hide the body.’ It was a lonely part of the bush, near the river. How Laurette get there if somebody didn’t carry her or was trying to hide her I don’t know. No road will take you straight there and no young girl going there alone unless she got a good reason. Even I was afraid to pass there in the middle of the morning with other boys, the place dig deep into the bottom of the hill. Quiet, strange, dark, cold, the wind freezing your skin even when sun high up in the sky. The kind of place Mama would say you bound to get ladjablès. If I know my sister, no way she going there by herself. People come home to tell Mama about what they hear and she put on a bold face. Then she repeat what they say to Papa, and he storm out the house.

Out of the blue a few days after Laurette’s death, Mama tell me that the police want to ask me some questions. They came to the house; it was a Saturday morning. All I could tell them was I never set eyes on Laurette again after she hit me with the little stone while I was bathing. I was in school when Papa find her. Don’t remember if I cry, but I felt sad. I told them I would miss her when I was not in school and, until she come back, from this dying business, I will not be myself again. She did all the housework — carrying water, washing dishes, our clothes, sweeping out the house and putting Marvin to sleep. I had nothing to do on afternoons except play.

They take me in the front room, alone, while another detective stay with Mama in the kitchen. A woman from social services, who the police tell me was a lawyer sit by me, while two big men corner me in the old Morris chair. I wanted to show the detectives that I was Mama’s little innocent boy boasting that boys don’t do housework, that’s for girls to do. I believed that, deep down, after seeing my father strut around the house doing nothing while Mama work her tail off in the kitchen. Boys learn to make garden with their fathers; look after sheep and goats in the pasture and feed the cow. I wanted the detectives to know Mama was a good person. How could a good person have anything to do with the death of her own child?

My father was not interested in what was happening in the house with us. Bringing up children was Mama’s job. He was quiet, and you never know when he in the house until he come in the kitchen to eat. The most he do was a little garden behind the kitchen and a day’s job here and there when he could find work. When Papa feel like bathing in the river, if no school, he would take me with him and show me how to catch crayfish with my bare hands and make traps for birds. My mind was still on church and God and first communion, bad things did not enter my head; I wasn't holy-holy, never was an acolyte, or anything like that. I say my prayers first thing on mornings before I pass water in my mouth and last thing at night before I close my eyes.

No way I could think Papa was evil; he did not look like a person who would do bad things. But then what can we tell by a person’s looks? However, looking back, I know enough to know my father was not a man to take for granted although I don’t remember him ever raising his hand on either me or Laurette. That job was Mama’s. The most he would do if we make too much noise is shout “Mama” and she came right away to put peace. Sometimes I wonder if I really know my father. I don’t think as a child there was ever a serious conversation between us, except on days by the river, but then I did most of the talking. He was seldom home long enough to teach me to lace my shoes or send me on errands.

I wake up from sleep in the dark soaking wet searching for Laurette using my hands. She sleep by herself in a corner on her own little pile of bedding, to beg her find an old dress for me, one she or my mother was not wearing again. I needed a dry old dress to put on; sleep never take me in wet clothes not even if I dry myself and stay naked. I call her name, soft, didn’t want to wake Mama — then I remember, Laurette was no longer here with us. Mama would sleep hard after she drain her tears, my little brother Marvin on the bed next to her — he sleeps with her when Papa not around — they could not hear the wind even if it tear the old galvanise roof off the house. How long I stay awake taking off wet clothes and falling back naked on the floor, I don’t know. It took many, many years for me to catch myself again.

Last time I saw Laurette was in the cemetery before they screw the lid on her coffin. She had on lipstick for the first time and a strange smile across her lips. I thought she spoke to me with her eyes closed but was too frightened to understand what she said. Not until I see men in the graveyard shovelling dirt on her coffin that I agree, halfway at least, maybe she die in truth, but still not fully understanding the consequences of death. I know I would not see her again for a long, long time. How she would manage alone, by herself, under all that pile of dirt was beyond me.

I never realise I remembered so much about Laurette’s funeral until I was much older. That afternoon, through my damp eyes, I was standing on the church steps holding Mama’s hand. Papa was right behind us, hiding, smoking a cigarette. Our cousin Miss Eldra and her youngest daughter, who was standing next to Mama, had Marvin on her shoulder fast asleep. I hear Miss Eldra chastise Papa and ask him to out the cigarette when the hearse arrive. Some older boys from the school take charge of the coffin when the driver open the back of the hearse. They climb the steps and stop at the entrance, the priest and acolytes come down with the cross, say some prayers and the boys carry the coffin up the aisle behind him.

Mama, me, Miss Eldra, her daughter with Marvin, follow behind the coffin. But not Papa, he stay outside with his friends. We sit down in a pew up front. The boys place Laurette’s coffin on a bier and went to sing with the school choir. Mama crying on Miss Eldra’s shoulder send me fighting back tears. I find it strange Papa did not come and sit with us and I keep looking back to see if he came inside but the church was so fill I couldn’t see past the pew behind us.

People come from everywhere, from as far as Castries, dressed in their Sunday best smelling of all kinds of perfume I never smell before until that afternoon. There were many speakers. I can’t remember anything that was said but when the priest began smoking the coffin, I couldn’t take the smell of the incense and my head went light. The next thing was the crowd in the cemetery begging Mama to open the coffin for them to see Laurette for the last. Neither Mama nor Papa had time for me that afternoon. Mama was busy talking to people she didn’t know; some brought wreaths, some handed her sympathy cards in white envelopes. Papa was making himself busy with the gravediggers, belching smoke through his nose like he was a chimney.

Fore-day morning, six months after Laurette’s funeral. Cocks were crowing loud in the yard; I turn a little on my side to ease out of the dream to hear like somebody knocking hard on the door. I was tempted to get up and check, but something tell me go back to sleep. Next, I wake up for good to a loud banging. Men shouting: “Open! Police!” Mama get up, shaking Papa; he was a hard sleeper. “Wake up, Lovence, police!” Papa yawn but quickly catch himself and put on his pants. I follow them to the door. Marvin was still asleep. Four officers in plainclothes rush inside as soon as Papa turn the key in the lock. One of them had a sheet of paper in his hand. “Are you Lovence St Mark?”

“What?” Papa look stunned, he couldn’t say much.

“What happen to Lovence St Mark? Yes, is his house…” Mama was ready to take on all four officers.

“This is your husband?” The officer with the paper ask.

“Yes, is Lovence.”

“Lovence St Mark, I have a warrant for your arrest for the murder of Laurette Stephen. From now on anything you say can be taken down and held in evidence against you.”

An officer took out a pair of handcuffs and secure Lovence St Mark’s hands behind his back. Mama went cold. I follow Papa when the police march him outside. There were six in all, two armed with rifles stayed outside; Mama try to hold me back in the doorway, but I slip through her hands.

Although still very early, a crowd gathered by the road. Children were there with their parents and later in school they were happy to tell me how the police manhandled Papa and shove him into the back of their jeep. It was not a good day for me. At school I hang my head in shame over my desk listening to the children speak about my father. They didn’t care if I got vex; they were with one voice: “The police walk him from his house, push him in the back seat an’ carry him down to the station, bouwo-a,” they rejoiced.

The news went wild, swinging on vines around Bwa Nèf, uphill to Tèt Chimen and deep into Gwan Bwa. Papa was arrested and condemned without a hearing or a trial and his whole family crucified in the process. In this little place behind God’s back, justice is one face you seldom see, and if you poor, you might never see it. Sometimes, time sits on your case and after several years will allow you a hearing. By then you would be lucky if witnesses remember your face. For my father it would be many years before his day came.

To say I remember Papa ever speak to me the morning police come for him, either in sympathy, pity or regret, would be a lie. He keep his face in front and didn’t look back. One of our cousins, Miss Eldra’s eldest daughter from Tèt Chimen, come by the school to collect me that afternoon and take me to her house. She was on her own living with her boyfriend. I stay with her because Mama went with Marvin to Dennery Police Station where they charge Papa without bail. Nobody could explain that to me and I did not understand what was going on. Who so stupid to believe Papa will kill his own child? You only kill your enemies, people who hurt you, those that do things to send you to the mad house, or worse, those that use obeah to destroy you.

However, I understood if you don’t believe in obeah, you safe. Couldn’t say I was safe, I had my own beliefs growing up in a house where good and evil speak from the same side of your mouth. Living in the country you learn to kill cockroach, rats, bugs, lots of birds and snakes, a fowl for first communion and Christmas, even manicou, but not people. “Thou shalt not kill” is in your face every day, from mother, teacher, and priest.

I hear a lot of things at school when Mama could afford to send me. The older girls, Laurette’s friends, said I would grow up to be just like my father. Mama threaten to come to the school to report them to the head teacher, but never did. Life get harder for us, and Mama seldom had money to buy lunch. It was only when she get a little work with Miss Grainy peeling spice, cleaning nutmegs and collecting mace that she would have small change to buy bread and a tin of sardines for me and Marvin to share during lunch break. She did not have to cook for twelve o’clock; Papa was not around to suddenly appear pretending he was hungry on days when nobody at Paulinos’ bar was buying him drinks.

Mama paid more attention to Papa than to us. She always find money wherever it was, from relatives or friends, to buy food, clothes, to take to Castries when she visit Papa in custody. Being the older brother, I had to teach Marvin how to fend for himself. Most days we ate whatever fruit was in season, fished for eels in the river which we cook sometimes without salt and collect ground provisions from our cousins at Tèt Chimen. I felt ashamed not being able to take care of the family during Papa’s absence — he never come back until I was grown up and living in my own house — but could not let my little brother see.

I try hard to forget that Papa was in prison all those years, but it still plays on my mind. Mama’s visits to Castries, up and down like a donkey on the high road while Papa remain locked up was not easy to understand either, especially not knowing when Papa would be released. That was the worst of all; it would hit me hard. Mama never stop crying at nights pouring her grief out to her pillow, repeating Papa’s name, missing her man more than she ever miss us. You’d swear we were nowhere around. If we dare ask her what was wrong, the huff she would let out was louder than any scream she make; so loud you would hear her voice all the way down in the village.

She pretend to neighbours who call to bring yams, or breadfruits when in season, that she no longer care about herself, no man would look at her again twice if anything happened to Lovence. The neighbours didn’t have to ask questions, she volunteered, and she did not hesitate to blame her children for her apparent self-neglect; one was dead, but she still blamed all three and detested the police for keeping her husband in custody. “Without asking questions, without taking him to court, because they say (stressing on the they) is he kill Laurette.”

Mama make it a habit of repeating how Papa take all his money and give to lawyers who fool him so there is nothing left to spend on us. That would be fair had it been true but Papa had no money in the first place. His lawyers were all court appointed, and some young ones worked pro bono hoping to make their name. I could not understand how Papa was accused of murdering Laurette and nobody, except for the children at school, could say how he manage to do it. There were rumours out of Mr Paulinos’ rum shop that Laurette was strangled; there were stories she might have been raped, but the men spoke soft whenever they saw me coming on errands. Nevertheless, not a soul on God’s earth could get me to believe Papa did this. The man couldn’t kill a cockroach even if it was to save Mama’s life.

Yet there was more to the story than I was being told. My little brain start working overtime and I begin asking myself questions. Why Mama insist on me telling the police I see Papa in the kitchen when I leave for school? I could not say he was; I was mixed up between what I thought I saw and what she wanted me to believe. Who set police on Papa was the question on my mind: a neighbour, somebody with a grudge, or the real murderer? Why so many things remain above my head, things I cannot understand? I needed answers but did not know where to go to find them.

Chapter

2

Three years after Laurette’s death I passed the Common Entrance exam and went to Dennery Secondary School. My mother arranged with my nennenn