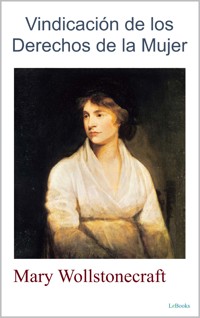

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman & A Vindication of the Rights of Men E-Book

Mary Wollstonecraft

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

For many years the victim of smear campaigns by notable male writers, and dismissed as being merely 'the mother of Mary Shelley', Mary Wollstonecraft has claimed her rightful title as one of the founders of feminist thought, a movement anchored in her Vindications. Outraged by Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, its use of gendered language and defence of monarchy and hereditary privilege, A Vindication of the Rights of Men turned the tables on philosophy. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman swiftly followed, taking the conversation further, and arguing the case for women's education. Together, these two seminal works went on to change the course of history, and her arguments continue to hold water today. This edition contains explanatory notes and an introduction by Bee Rowlatt, Chair of the Wollstonecraft Society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 641

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman & A Vindication of the Rights of Men

mary wollstonecraft

with an introduction by

bee rowlatt

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

A Vindication of the Rights of Men first published in 1790

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman first published in 1792

This edition first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2022

Edited text © Renard Press Ltd, 2022

Introduction © Bee Rowlatt, 2022

Cover design by Will Dady

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

contents

Introduction

A Vindication of the Rights of Men

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Introduction

chapter 1

chapter2

chapter 3

chapter 4

chapter 5

chapter 6

chapter 7

chapter 8

chapter 9

chapter 10

chapter 11

chapter 12

chapter 13

note on the texts

notes

introduction

Vindication vɪndɪˈkeɪʃ(ə)n noun

The action of clearing someone of blame or suspicion.

Proof that someone or something is right, reasonable or justified.

Why Wollstonecraft, and why now?

Why Wollstonecraft? That’s easy. The past is teeming with books that deserve to be read, but how many of them were written at a hundred miles an hour by a messy-haired woman on a mission to change the world and everyone in it? Wollstonecraft wrote her Vindication of the Rights of Men in 1790 and A Vindication of the Rights of Woman two years later. Together they are an unparalleled equal-rights double bill. Do you like your writers pounding out their blistering-hot ideas around a sensationalist life, eating taboos for breakfast while changing the shape of the horizon on the daily? You have found that writer. As Lizzo says, ‘It’s bad bitch o’clock.’

And why now? Where to begin… In summer 2022 the writer Rebecca Solnit visited the graveyard of St Pancras Old Church, a quiet space behind two of London’s busiest train stations. She took a selfie by Wollstonecraft’s gravestone, posting it with the words: ‘Feminism has a long history.’ It was in the immediate aftermath of that volcanic eruption of misogyny: the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Was this visit some form of homing device, the magnetic pull of a reassuring voice from the past that won’t change, won’t let us down?

Feminism is a global movement that is in flux, everywhere, all the time. It turns out that even the most basic equalities can go backwards as well as forwards, with Afghan girls out of school, FGM persisting and online incel cultures on the rise. The very idea of human rights is being swept into a self-defeating confection known as ‘culture wars’. That infamous Supreme Court ruling is far from being the only barometer of the anti-rights backlash. But I was struck by Solnit’s visit, and why it felt important. It’s because this is where we go in times of crisis – we go to the source.

Who is she?

Wollstonecraft is our ancestor: she is the foremother of feminism, a key Enlightenment philosopher, abolitionist and very early architect of what we now call human rights. But the first thing you need to know about Wollstonecraft is that she is an optimist, despite having so little cause to be so. She was born in 1759, into a background of violence and alcoholism. Although her family didn’t believe in educating girls, they didn’t seem to mind living off her earnings once she educated herself.

Somehow Wollstonecraft’s ‘ardent affection for the human race’ persists, despite the early years of neglect and domestic abuse. In later life she experiences hunger, depression and the perils of attempting to lead an experimental life. At every turn she discovers what it means to be the less-valued kind of human being; it is the source of the high-voltage rage that fuels her writing.

After an itinerant childhood, a spell as a lady’s companion and time spent caring for her mother and sister, Wollstonecraft finally ends up in Newington Green, among a community of Radical Dissenters drawn there by the benevolent minister Richard Price. The fact that these people are ‘excluded as a class from education and civil rights by a lazy-minded majority was something for an embryonic feminist to brood upon.’1

By virtue of her intellectual curiosity (also of being the most argumentative person at the party) Wollstonecraft becomes part of a luminous circle including William Blake, Tom Paine and members of the founding generation of the United States of America. Her lifelong dream of financial independence results in the founding of a school and the start of her writing career. Her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, is a strong indicator of the future direction of travel.

Although Wollstonecraft is rarely out of trouble and nearly always skint, she is self-aware and at times very funny. She jokes at her own expense in a letter to a lover – ‘still harping on the same subject, you will exclaim!’2 – and even in the Vindications there are laughs – her eye-rolls and sarcastic asides still burn to this day.

She is an enemy of traditions and the ‘rust of antiquity’, and as she bursts off the page you can almost feel that rush in lines like: ‘I pause to recollect myself, and smother the contempt I feel rising for your rhetorical flourishes.’ Wollstonecraft is not content just to be an observer. She doesn’t sit around celebrating the ideals of the French Revolution, she gallops off solo to live there, right in the bloody midst of it, becoming along the way a destitute single mum and de facto war correspondent.

Another love affair gone wrong, a treasure hunt around the wild shores of the Skagerrak with her toddler in tow and two attempts on her own life, followed by a return to authorial prowess and an innovative form of domestic harmony all look like the blissful ending to her Hollywood blockbuster story. But then, in the most bitter twist of all, Wollstonecraft dies in childbirth, giving birth to the future Mary Shelley. It is fair to say ‘Wollstonecraft’s was an interrupted life.’3 She was only 38.

Following her death Wollstonecraft’s newly minted husband William Godwin writes a heartfelt account of her life, including her love lives and her mental health battles. His Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman is an unusually fresh work of biography, but its revelations spark a scandal and years of vicious trolling. Back then, her personal life appalled people; now it teaches us how far we have come and what is still at stake. Her story is more than just extraordinary, it is crucial to the understanding of her work.

The most famous of the two vindications, The Rights of Woman, rippled all around the world during the era of revolutions. The scholar Eileen Hunt traces its reception in Kingstown, Jamaica, just before the Haitian revolution; in a Madras newspaper in India in 1794; and almost a century later in the Bombay Circulating Library, as the Indian independence movement gathered strength.

It ripples down through time as well. In the 1960s the African-American playwright Lorraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun, worked on a three-part play about Wollstonecraft, incomplete because of Hansberry’s untimely death. Hunt credits ‘Hansberry’s interest in Wollstonecraft as the origin of her feminist ideas. [The play] features the fifteen-year-old Wollstonecraft sticking out her tongue at her patronising older brother.’4

The image of a teenager sticking out her tongue embodies the spirit of defiance that Wollstonecraft never lost. It wasn’t enough to hold her employers, other writers, the church, political powers and the monarchy to account – she also challenged everyone she met. Her sisters regularly fell out with her, and various boyfriends and girlfriends took fright at her intensity. ‘I must have first place or none!’ she demanded of one of her first loves, Jane Arden.

Wollstonecraft transgressed the social norms of the day with the women she loved, her hostility to marriage, her extra-marital pregnancies. The same fluidity is present in her genre-defying writing. The novelist Kamila Shamsie describes Wollstonecraft’s The Wrongs of Woman as ‘a revolutionary work – most striking for the friendship she creates between two women from vastly different class backgrounds who discover common ground in the injustices they face as women… It is terrifying, funny, finely judged in its execution.’5

The Vindications are key milestones, not only in the formation of a language that describes what makes us human, but also in Wollstonecraft’s own development as a writer. They predate her time in revolutionary Paris, her doomed Scandinavian treasure hunt, her attempts on her life and her journey into motherhood. These episodes will change and deepen her work, while her lived experience continues to influence her writing.

The Vindications therefore represent only part of the breadth of Wollstonecraft’s writing, but they are her launchpad. Together they are an escalating call to arms, revealing her dynamic intention: her ‘favourite subject of contemplation, the future improvement of the world,’ (Letter XXII, Letters). Wollstonecraft hoped to be useful, and she longed for a future in which her work would not be needed.

We’re not there yet. So far that future has brought with it an ongoing stream of new interpretations of her work, ‘constantly remoulded in feminism’s changing image,’ and yet, ‘Wollstonecraft remains as vital and necessary a presence today as she was in the 1790s.’6

The Rights of Men‘My heart is human’

This is the ultimate starter pack: a human-rights espresso shot that you can down in one. There are two important things to know before you read it. One: she doesn’t mean men, she means humans. Two: it is a letter to Edmund Burke, the forefather of conservatism. This powerful establishment voice, horrified by developments on the other side of the Channel, has just published his Reflections on the Revolution in France, and it comes in the shape of a personal attack on Wollstonecraft’s dearest mentor, the Reverend Richard Price.

Wollstonecraft is furious. The text reads like a distillation of all the denials of her life and selfhood so far. It is her first significant publication, and it seems to burst out of her in one go. A delicious account of its writing has Wollstonecraft getting cold feet about the scale of this battle, and nearly giving up. She calls on her doughty publisher Joseph Johnson to suggest that they scrap what she has already submitted: ‘Johnson knew how to handle his impetuous employee. Instead of urging her ahead, thus provoking reaffirmation, he treated her with friendliness and agreed that she should not struggle against her feelings. As for what he had already printed, he would “cheerfully” destroy it if this would make her happy. The response threw her. She immediately saw that what she has written had meant much to her and was piqued that anyone should agree to destroy it.’7

Incensed, she returns to and finishes the job at white-hot speed. The Rights of Men lands on the 29th of November 1790, less than a month after Burke’s Reflections and several months ahead of Paine’s coming-in-second-place Rights of Man.

Into this condensed pamphlet of only around 23,000 words Wollstonecraft fits some startling ingredients. The pasting that she delivers along the way to Burke is something to behold – ‘This is sound reasoning, I grant, in the mouth of the rich and short-sighted’ – but it is not the main star of the show.

She tackles privilege, echo chambers, being called out, how to think and the meaning of happiness. She takes on royalty, inherited wealth and the caste system. She attacks the ‘infernal slave trade’ as ‘a traffic that outrages every suggestion of reason and religion.’ She demands to know how we could be doing better in our politics – is ‘our constitution not only the best modern one but the best possible one?’ She scorches the unquestioning love for one’s own country, and takes a sandblaster to the political and religious machineries of the day.

Most importantly, her arguments are underpinned throughout by the same thrilling idea, the ‘native unalienable rights of men’. All humans are born with the innate capacity for reason, and our ‘improvable faculties’ are part of our humanity. Wollstonecraft worships human rights as god-given, and therefore the highest possible authority: ‘I reverence the rights of men.’

‘Among unequals there can be no society,’ she insists, and to overcome social inequality we must ‘cultivate our reason’. What we have here is the blueprint for universal human rights, before the language for such a radical idea even existed.

At first the pamphlet is published anonymously, and naturally everyone assumes it was written by a man. (She adopts a sometimes-mocking male voice – ‘Sir, let me ask you, with manly plainness’!) But it quickly sells out, and the second print run features her name. There is a shocked response – this is when the ‘hyena in petticoats’ commentary begins – but Wollstonecraft has arrived; she is on the map.

She is not yet famous or well connected. She is young, largely self-taught, and chippy with it. She comes from the wrong side of the tracks. And here she is, hurling bolts of raging lightning at every vested interest in the land. Wollstonecraft’s The Rights of Men contains the ideas that will flourish in her later work; they are present here in her fearless, loud voice. It is monumental.

The Rights of Woman‘I declare against all power built on prejudices’

Two years later Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Men yields a sharp-thorned harvest with her publication of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. With a keen eye on gaining international traction she dedicates the text to the French diplomat Talleyrand, pointedly addressing him ‘as a legislator’ in the hopes of influencing France’s constitution. She again equates ‘the tyranny of governments and the tyranny of men over women.’8 This time she is advocating for ‘one half of the human race’.

The Rights of Woman has two central theses. One: women are humans. Two: therefore they deserve to (and must) be educated. She demands that women take part in humanity, ‘by reforming themselves to reform the world’. Wollstonecraft is again in full pioneering mode: it will be another century before the word ‘feminism’ appears. The purpose of this Vindication is to elaborate on the first book-length case for gender equality in the English language.

The same incandescent anger lights up its pages, and Wollstonecraft devotes lengthy passages to attacking other writers, upper-class women, unquestioning thinking. Above all else, Wollstonecraft is an educator – her entire body of work is preoccupied with the critical importance of education. The Rights of Woman approaches this theme from numerous angles – even outlining an audacious proposal for state-funded co-education of girls and boys. She worries about girls reading sentimental novels and only valuing their appearances. She emphasises physical well-being and encourages girls to dress appropriately for exercise. Financial independence (‘the grand blessing of life’) and being useful to society are recurring themes. The focus is wide-angled: ‘I plead for my sex, not for myself.’

This book made Wollstonecraft into an international celebrity, and paved the way for her life-changing French Revolution episode. But curiously, while it is by far her best-known work, it is the least easy to read. Even William Godwin, her husband and arguably her biggest fan, calls it ‘undoubtedly a very unequal performance’. The text is dense and some parts have not aged well, such as her disapproval of sex (this, by the way, will change when she gets to Paris).

On first reading, parts of The Rights of Woman may appear to lack intersectionality (for a developing inclusivity read her later work The Wrongs of Woman). But you can approach this text as a series of explorations, attacks and defences, a radical jumble sale with regular surprises, bargains, treats and baffling areas. It is a piece of work to return to, across decades and throughout phases of your life. You will always spot something new; you will never get bored.

Together the Vindications create a window into the life of a self-made genius, a look into a world where women had all the legal status of an armchair, and a defiant and possible vision of the future. At their core, both these signature Enlightenment works celebrate the Wollstonecraftian themes of usefulness, of improvability, of education.

The economist Amartya Sen, who was awarded a Nobel Prize for his work on inequality, has long valued Wollstonecraft as one of the most underestimated thinkers of the eighteenth century, describing her Vindications as ‘two treatises on human rights’ that demand ‘that everyone be seen as morally and politically relevant.’9

In an earlier essay he writes ‘one particular insight that Mary Wollstonecraft had is the basic commonality of different kinds of social deprivation and societal inequality, which have a uniting feature. The relevance of feminist thinking is not confined to gender inequality only, nor only to the pursuit of perspectives that a women’s position or a feminist commitment can bring out. It also links with problems of other types of deep inequality.’10

While deep inequality persists, and, in some cases, worsens, we return to Wollstonecraft. We visit her memorial places and we read her works. We return to Wollstonecraft for her colossal ideas, and for the sheer guts that it required to share them.

Wollstonecraft in the world

My own history with Wollstonecraft has been all about escaping out of the pages and into the world. I retraced her and her first child’s Scandinavian adventures in In Search of Mary; led the Mary on the Green campaign for Maggi Hambling’s memorial artwork, and now chair the educational charity the Wollstonecraft Society, creating primary-school materials inspired by her. I have shared Wollstonecraft’s story over the years with audiences everywhere from Glasgow to Dhaka, Bradford to Moscow. My wish is that the ideas contained within Wollstonecraft’s pages will spring out, come alive, put down roots and persist. That they will give both inspiration and comfort. That they will be a destination and a homecoming.

This new edition of the Vindications shows Wollstonecraft ‘alive and active’, just as Woolf says – ‘she argues and experiments, we hear her voice and trace her influence even now among the living.’11 She is alive and active in the world, out in the buzzing spaces, alive in our minds and active in the actions and words that we use for and against each other. Her work features in new publications, in new artworks, even a comic book (currently being distributed to school libraries by the Wollstonecraft Society).

In recent years there has been a surge in books, plays, art, memes and newly formed organisations promoting Wollstonecraft’s work. On top of her own research, scholar Emma Clery has made a community of various groups, including the Mary Wollstonecraft Fellowship, the Wollstonecraft Philosophical Society and the Wollstonecraft Society. Thanks to her there is an ever-expanding web of Wollstonecraft ideas and energy; a cause for optimism and a wonderful tribute to one of history’s unlikely optimists.

As Wollstonecraft casually mentions as an aside in The Rights of Woman, ‘Rousseau exerts himself to prove that all was right originally, a crowd of authors that all is now right – and I, that all will be right.’

Things should get better, not worse. Humans should propel ourselves forwards; we aren’t built for backwards steps. And yet here we are, and sometimes it’s enough to make you want to sit on the floor with your back to the world. But we can’t do that. And you, with this resplendent Renard Press edition in your hand, you are not doing that. These combined works are not only a call to arms, but also a return to the basics; the philosophical underpinnings of what it means to be a human among other humans. This is where it starts. Feminism has a long history. That history extends up ahead and in front of us; you are holding a piece of it in your hands.

bee rowlatt

bee rowlatt is a writer and journalist, and has clocked over two decades at the BBC World Service. Her writing has been published widely, including pieces for BBC Online, The Telegraph, Grazia, Die Welt, the Times, the Guardian and the Daily Mail, with regular appearances on TV and radio. Her critically acclaimed travelogue In Search of Mary (Alma Books), inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft, won the Society of Authors’ K. Blundell Trust Award. She also wrote a play about Wollstonecraft, An Amazon Stept Out, which was performed at the Lyric Theatre on London’s Shaftesbury Avenue. The bestseller Talking About Jane Austen in Baghdad (Penguin) was dramatised by the BBC and has been translated into numerous languages. She also contributed to Virago’s Fifty Shades of Feminism. Bee has judged the Poetry Society Young Poets’ award and the Stanford Dolman Travel Book of the Year award. Bee is currently working on a new book and also programmes events at the British Library. She is a leading light in initiatives celebrating and continuing Wollstonecraft’s work: she chaired the Mary on the Green campaign to memorialise Mary Wollstonecraft, and is a founding trustee of the human-rights education charity the Wollstonecraft Society.

www.beerowlatt.com

www.wollstonecraftsociety.org

1Claire Tomalin, The Life and Death of Mary Wollstonecraft (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1974), p. 61.

2Mary Wollstonecraft, ‘Letter XIX’ from Letters written in Sweden, Norway and Denmark (London: Joseph Johnson, 1796). Further references are given in the text as ‘Letters’.

3Lyndall Gordon, Vindication: A Life of Mary Wollstonecraft (London: Little, Brown, 2005), p. 390.

4Eileen Hunt, Portraits of Wollstonecraft, Volume 1 (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), p. xix.

5Kamila Shamsie in the theatre programme for An Amazon Stept Out by Bee Rowlatt, directed by Honor Borwick, Lyric Theatre, London, 30th September 2019 (London: Wollstonecraft Society, 2019).

6Barbara Taylor, Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 253.

7Janet Todd, Mary Wollstonecraft: A Revolutionary Life (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000), p. 164.

8Charlotte Gordon, Romantic Outlaws: The Extraordinary Lives of Mary Wollstonecraft & Mary Shelley (London: Hutchinson, 2015), p. 173.

9Amartya Sen, The Idea of Justice (London: Allen Lane, 2009).

10Amartya Sen, ‘Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary!’, Feminist Economics, 11:1 (2005), 1–9. <DOI: 10.1080/1354570042000332551>

11Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader: Second Series (London: The Hogarth Press, 1932).

a vindication of the rights of men

Advertisement

Mr burke’s reflections on the French Revolution* first engaged my attention as the transient topic of the day, and reading it more for amusement than information, my indignation was roused by the sophistical arguments that every moment crossed me in the questionable shape of natural feelings and common sense.

Many pages of the following letter were the effusions of the moment, but, swelling imperceptibly to a considerable size, the idea was suggested of publishing a short vindication of the Rights of Men.

Not having leisure* or patience to follow this desultory writer through all the devious tracks in which his fancy has started fresh game, I have confined my strictures, in a great measure, to the grand principles at which he has levelled many ingenious arguments in a very specious garb.

A Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke

Sir,

It is not necessary, with courtly insincerity, to apologise to you for thus intruding on your precious time, not to profess that I think it an honour to discuss an important subject with a man whose literary abilities have raised him to notice in the state.* I have not yet learned to twist my periods, nor, in the equivocal idiom of politeness, to disguise my sentiments and imply what I should be afraid to utter. If, therefore, in the course of this epistle I chance to express contempt, and even indignation, with some emphasis, I beseech you to believe that it is not a flight of fancy, for truth, in morals, has ever appeared to me the essence of the sublime, and, in taste, simplicity the only criterion of the beautiful. But I war not with an individual when I contend for the rights of men* and the liberty of reason. You see I do not condescend to cull my words to avoid the invidious phrase, nor shall I be prevented from giving a manly definition of it, by the flimsy ridicule which a lively fancy has interwoven with the present acceptation of the term. Reverencing the rights of humanity, I shall dare to assert them, not intimidated by the horse laugh* that you have raised, or waiting till time has wiped away the compassionate tears which you have elaborately laboured to excite.

From the many just sentiments interspersed through the letter before me, and from the whole tendency of it, I should believe you to be a good – though a vain – man, if some circumstances in your conduct did not render the inflexibility of your integrity doubtful; and for this vanity a knowledge of human nature enables me to discover such extenuating circumstances, in the very texture of your mind, that I am ready to call it amiable, and separate the public from the private character.

I know that a lively imagination renders a man particularly calculated to shine in conversation and in those desultory productions where method is disregarded, and the instantaneous applause which his eloquence* extorts is at once a reward and a spur. Once a wit and always a wit is an aphorism that has received the sanction of experience; yet I am apt to conclude that the man who with scrupulous anxiety endeavours to support that shining character can never nourish by reflection any profound or, if you please, metaphysical passion. Ambition becomes only the tool of vanity, and his reason, the weathercock of unrestrained feelings, is only employed to varnish over the faults which it ought to have corrected.

Sacred, however, would the infirmities and errors of a good man be, in my eyes, if they were only displayed in a private circle; if the venial fault only rendered the wit anxious, like a celebrated beauty, to raise admiration on every occasion, and excite emotion, instead of the calm reciprocation of mutual esteem and unimpassioned respect. Such vanity enlivens social intercourse, and forces the little great man to be always on his guard to secure his throne; and an ingenious man, who is ever on the watch for conquest, will, in his eagerness to exhibit his whole store of knowledge, furnish an attentive observer with some useful information, calcined* by fancy and formed by taste.

And though some dry reasoner might whisper that the arguments were superficial, and should even add that the feelings which are thus ostentatiously displayed are often the cold declamation of the head, and not the effusions of the heart – what will these shrewd remarks avail when the witty arguments and ornamental feelings are on a level with the comprehension of the fashionable world, and a book is found very amusing? Even the ladies, sir, may repeat your sprightly sallies, and retail in theatrical attitudes many of your sentimental exclamations. Sensibility is the manie* of the day, and compassion the virtue which is to cover a multitude of vices, whilst justice is left to mourn in sullen silence, and balance truth in vain.

In life, an honest man with a confined understanding is frequently the slave of his habits and the dupe of his feelings, whilst the man with a clearer head and colder heart makes the passions of others bend to his interest; but truly sublime is the character that acts from principle and governs the inferior springs of activity without slackening their vigour; whose feelings give vital heat to his resolves, but never hurry him into feverish eccentricities.

However, as you have informed us that respect chills love, it is natural to conclude that all your pretty flights arise from your pampered sensibility, and that, vain of this fancied pre-eminence of organs, you foster every emotion till the fumes, mounting to your brain, dispel the sober suggestions of reason. It is not in this view surprising that when you should argue you become impassioned, and that reflection inflames your imagination, instead of enlightening your understanding.

Quitting now the flowers of rhetoric, let us, sir, reason together; and, believe me, I should not have meddled with these troubled waters in order to point out your inconsistencies if your wit had not burnished up some rusty, baneful opinions, and swelled the shallow current of ridicule till it resembled the flow of reason, and presumed to be the test of truth.

I shall not attempt to follow you through ‘horse-way and footpath’;* but, attacking the foundation of your opinions, I shall leave the superstructure to find a centre of gravity on which it may lean till some strong blast puffs it into the air; or your teeming fancy, which the ripening judgement of sixty years* has not tamed, produces another Chinese erection* to stare, at every turn, the plain country people in the face, who bluntly call such an airy edifice a folly.

The birthright of man, to give you, sir, a short definition of this disputed right, is such a degree of liberty, civil and religious, as is compatible with the liberty of every other individual with whom he is united in a social compact, and the continued existence of that compact.*

Liberty, in this simple, unsophisticated sense, I acknowledge, is a fair idea that has never yet received a form in the various governments that have been established on our beauteous globe; the demon of property has ever been at hand to encroach on the sacred rights of men, and to fence round with awful pomp laws that war with justice. But that it results from the eternal foundation of right – from immutable truth – who will presume to deny that pretends to rationality – if reason has led them to build their morality12 and religion on an everlasting foundation – the attributes of God?

I glow with indignation when I attempt, methodically, to unravel your slavish paradoxes, in which I can find no fixed first principle to refute; I shall not, therefore, condescend to show where you affirm in one page what you deny in another; and how frequently you draw conclusions without any previous premises – it would be something like cowardice to fight with a man who had never exercised the weapons with which his opponent chose to combat, and irksome to refute sentence after sentence in which the latent spirit of tyranny appeared.

I perceive, from the whole tenor of your Reflections, that you have a mortal antipathy to reason; but, if there is anything like argument, or first principles, in your wild declamation, behold the result: that we are to reverence the rust of antiquity, and term the unnatural customs which ignorance and mistaken self-interest have consolidated, the sage fruit of experience: nay, that if we do discover some errors, our feelings should lead us to excuse, with blind love, or unprincipled filial affection, the venerable vestiges of ancient days. These are Gothic notions of beauty – the ivy is beautiful, but, when it insidiously destroys the trunk from which it receives support, who would not grub it up?

Further, that we ought cautiously to remain for ever in frozen inactivity, because a thaw, whilst it nourishes the soil, spreads a temporary inundation; and the fear of risking any personal present convenience should prevent a struggle for the most estimable advantages. This is sound reasoning, I grant, in the mouth of the rich and short-sighted.

Yes, sir, the strong gained riches, the few have sacrificed the many* to their vices; and, to be able to pamper their appetites, and supinely exist without exercising mind or body, they have ceased to be men. Lost to the relish of true pleasure, such beings would, indeed, deserve compassion, if injustice was not softened by the tyrant’s plea – necessity; if prescription was not raised as an immortal boundary against innovation. Their minds, in fact, instead of being cultivated, have been so warped by education that it may require some ages to bring them back to nature, and enable them to see their true interest with that degree of conviction which is necessary to influence their conduct.

The civilisation which has taken place in Europe has been very partial, and, like every custom that an arbitrary point of honour has established, refines the manners at the expense of morals, by making sentiments and opinions current in conversation that have no root in the heart, or weight in the cooler resolves of the mind. And what has stopped its progress? Hereditary property – hereditary honours. The man has been changed into an artificial monster by the station in which he was born, and the consequent homage that benumbed his faculties like the torpedo’s* touch – or a being with a capacity of reasoning would not have failed to discover, as his faculties unfolded, that true happiness arose from the friendship and intimacy which can only be enjoyed by equals; and that charity is not a condescending distribution of alms, but an intercourse of good offices and mutual benefits, founded on respect for justice and humanity.

Governed by these principles, the poor wretch, whose inelegant distress extorted from a mixed feeling of disgust and animal sympathy present relief, would have been considered as a man, whose misery demanded a part of his birthright, supposing him to be industrious; but should his vices have reduced him to poverty, he could only have addressed his fellow men as weak beings, subject to like passions, who ought to forgive, because they expect to be forgiven, for suffering the impulse of the moment to silence the suggestions of conscience, or reason, which you will; for, in my view of things, they are synonymous terms.

Will Mr Burke be at the trouble to inform us how far we are to go back to discover the rights of men, since the light of reason is such a fallacious guide that none but fools trust to its cold investigation?

In the infancy of society, confining our view to our own country, customs were established by the lawless power of an ambitious individual, or a weak prince was obliged to comply with every demand of the licentious, barbarous insurgents, who disputed his authority with irrefragable arguments at the point of their swords, or the more specious requests of the Parliament, who only allowed him conditional supplies.

Are these the venerable pillars of our constitution? And is Magna Carta to rest for its chief support on a former grant,* which reverts to another, till chaos becomes the base of the mighty structure – or we cannot tell what? For coherence, without some pervading principle of order, is a solecism.

Speaking of Edward III,* Hume observes that ‘he was a prince of great capacity, not governed by favourites, not led astray by any unruly passion, sensible that nothing could be more essential to his interests than to keep on good terms with his people: yet, on the whole, it appears that the government, at best, was only a barbarous monarchy, not regulated by any fixed maxims, or bounded by any certain or undisputed rights, which in practice were regularly observed. The king conducted himself by one set of principles; the barons by another; the commons by a third; the clergy by a fourth. All these systems of government were opposite and incompatible: each of them prevailed in its turn, as incidents were favourable to it: a great prince rendered the monarchical power predominant: the weakness of a king gave reins to the aristocracy: a superstitious age saw the clergy triumphant: the people, for whom chiefly government was instituted, and who chiefly deserve consideration, were the weakest of the whole.’*

And just before that most auspicious era, the fourteenth century, during the reign of Richard II,* whose total incapacity to manage the reins of power and keep in subjection his haughty barons rendered him a mere cypher; the House of Commons, to whom he was obliged frequently to apply, not only for subsidies but assistance to quell the insurrections that the contempt in which he was held naturally produced, gradually rose into power; for whenever they granted supplies to the king, they demanded in return, though it bore the name of petition, a confirmation or the renewal of former charters which had been infringed, and even utterly disregarded by the king and his seditious barons, who principally held their independence of the Crown by force of arms, and the encouragement which they gave to robbers and villains, who infested the country, and lived by rapine and violence.

To what dreadful extremities were the poorer sort reduced, their property, the fruit of their industry, being entirely at the disposal of their lords, who were so many petty tyrants!

In return for the supplies and assistance which the king received from the commons, they demanded privileges, which Edward, in his distress for money to prosecute the numerous wars in which he was engaged during the greater part of his reign, was constrained to grant them; so that by degrees they rose to power, and became a check on both king and nobles. Thus was the foundation of our liberty established, chiefly through the pressing necessities of the king, who was more intent on being supplied for the moment, in order to carry on his wars and ambitious projects, than aware of the blow he gave to kingly power by thus making a body of men feel their importance who afterwards might strenuously oppose tyranny and oppression, and effectually guard the subject’s property from seizure and confiscation. Richard’s weakness completed what Edward’s ambition began.

At this period, it is true, Wycliffe opened a vista for reason by attacking some of the most pernicious tenets of the church of Rome;* still the prospect was sufficiently misty to authorise the question: where was the dignity of thinking of the fourteenth century?

A Roman Catholic, it is true, enlightened by the Reformation, might, with singular propriety, celebrate the epoch that preceded it, to turn our thoughts from former atrocious enormities; but a Protestant must acknowledge that this faint dawn of liberty only made the subsiding darkness more visible; and that the boasted virtues of that century all bear the stamp of stupid pride and headstrong barbarism. Civility was then called condescension, and ostentatious almsgiving humanity; and men were content to borrow their virtues, or, to speak with more propriety, their consequence, from posterity, rather than undertake the arduous task of acquiring it for themselves.

The imperfection of all modern governments must, without waiting to repeat the trite remark that all human institutions are unavoidably imperfect, in a great measure have arisen from this simple circumstance, that the constitution, if such a heterogeneous mass deserve that name, was settled in the dark days of ignorance, when the minds of men were shackled by the grossest prejudices and most immoral superstition. And do you, sir, a sagacious philosopher, recommend night as the fittest time to analyse a ray of light?*

Are we to seek for the rights of men in the ages when a few marks were the only penalty imposed for the life of a man, and death for death when the property of the rich was touched? When – I blush to discover the depravity of our nature – when a deer was killed?* Are these the laws that it is natural to love, and sacrilegious to invade? Were the rights of men understood when the law authorised or tolerated murder? Or is power and right the same in your creed?

But in fact all your declamation leads so directly to this conclusion that I beseech you to ask your own heart, when you call yourself a friend of liberty, whether it would not be more consistent to style yourself the champion of property, the adorer of the golden image which power has set up? And, when you are examining your heart, if it would not be too much like mathematical drudgery, to which a fine imagination very reluctantly stoops, enquire further – how it is consistent with the vulgar notions of honesty and the foundation of morality – truth – for a man to boast of his virtue and independence, when he cannot forget that he is at the moment enjoying the wages of falsehood;13 and that, in a skulking, unmanly way, he has secured himself a pension of fifteen hundred pounds per annum on the Irish establishment.* Do honest men, sir, for I am not rising to the refined principle of honour, even receive the reward of their public services, or secret assistance, in the name of another?

But to return from a digression which you will more perfectly understand than any of my readers – on what principle you, sir, can justify the Reformation, which tore up by the roots an old establishment, I cannot guess – but, I beg your pardon, perhaps you do not wish to justify it, and have some mental reservation to excuse you, to yourself, for not openly avowing your reverence. Or, to go further back, had you been a Jew, you would have joined in the cry, ‘Crucify him! Crucify him!’ The promulgator of a new doctrine, and the violator of old laws and customs that, not melting, like ours, into darkness and ignorance, rested on divine authority, must have been a dangerous innovator in your eyes, particularly if you had not been informed that the Carpenter’s Son was of the stock and lineage of David. But there is no end to the arguments which might be deduced to combat such palpable absurdities by showing the manifest inconsistencies which are necessarily involved in a direful train of false opinions.

It is necessary emphatically to repeat that there are rights which men inherit at their birth, as rational creatures who were raised above the brute creation by their improvable faculties; and that, in receiving these, not from their forefathers but from God, prescription can never undermine natural rights.

A father may dissipate his property without his child having any right to complain; but should he attempt to sell him for a slave, or fetter him with laws contrary to reason, nature, in enabling him to discern good from evil, teaches him to break the ignoble chain, and not to believe that bread becomes flesh, and wine blood, because his parents swallowed the Eucharist with this blind persuasion.

There is no end to this implicit submission to authority – somewhere it must stop, or we return to barbarism; and the capacity of improvement, which gives us a natural sceptre on earth, is a cheat, an ignis fatuus* that leads us from inviting meadows into bogs and dunghills. And if it be allowed that many of the precautions, with which any alteration was made in our government, were prudent, it rather proves its weakness than substantiates an opinion of the soundness of the stamina, or the excellence of the constitution.

But on what principle Mr Burke could defend American independence* I cannot conceive, for the whole tenor of his plausible arguments settles slavery on an everlasting foundation. Allowing his servile reverence for antiquity and prudent attention to self-interest, to have the force which he insists on, the slave trade ought never to be abolished; and, because our ignorant forefathers, not understanding the native dignity of man, sanctioned a traffic that outrages every suggestion of reason and religion, we are to submit to the inhuman custom, and term an atrocious insult to humanity the love of our country, and a proper submission to the laws by which our property is secured. Security of property! Behold, in a few words, the definition of English liberty. And to this selfish principle every nobler one is sacrificed. The Briton takes place of the man, and the image of God is lost in the citizen! But it is not that enthusiastic flame which in Greece and Rome consumed every sordid passion: no, self is the focus; and the disparting rays rise not above our foggy atmosphere. But softly – it is only the property of the rich that is secure; the man who lives by the sweat of his brow has no asylum from oppression; the strong man may enter – when was the castle of the poor sacred?* – and the base informer steal him from the family that depend on his industry for subsistence.

Fully sensible as you must be of the baneful consequences that inevitably follow this notorious infringement on the dearest rights of men, and that it is an infernal blot on the very face of our immaculate constitution, I cannot avoid expressing my surprise that when you recommended our form of government as a model you did not caution the French against the arbitrary custom of pressing men for the sea service. You should have hinted to them that property in England is much more secure than liberty, and not have concealed that the liberty of an honest mechanic* – his all – is often sacrificed to secure the property of the rich. For it is a farce to pretend that a man fights for his country, his hearth or his altars when he has neither liberty nor property. His property is in his nervous* arms – and they are compelled to pull a strange rope at the surly command of a tyrannic boy, who probably obtained his rank on account of his family connections, or the prostituted vote of his father, whose interest in a borough, or voice as a senator, was acceptable to the minister.

Our penal laws punish with death the thief who steals a few pounds;* but to take by violence, or trepan,* a man is no such heinous offence. For who shall dare to complain of the venerable vestige of the law that rendered the life of a deer more sacred than that of a man? But it was the poor man with only his native dignity who was thus oppressed – and only metaphysical sophists and cold mathematicians can discern this insubstantial form; it is a work of abstraction – and a gentleman of lively imagination must borrow some drapery from fancy before he can love or pity a man. Misery, to reach your heart, I perceive, must have its cap and bells; your tears are reserved, very naturally, considering your character, for the declamation of the theatre, or for the downfall of queens, whose rank alters the nature of folly, and throws a graceful veil over vices that degrade humanity; whilst the distress of many industrious mothers, whose helpmates have been torn from them, and the hungry cry of helpless babes, were vulgar sorrows that could not move your commiseration, though they might extort an alms. ‘The tears that are shed for fictitious sorrow are admirably adapted,’ says Rousseau, ‘to make us proud of all the virtues which we do not possess.’*

The baneful effects of the despotic practice of pressing we shall, in all probability, soon feel; for a number of men who have been taken from their daily employments will shortly be let loose on society, now that there is no longer any apprehension of a war.

The vulgar – and by this epithet I mean not only to describe a class of people who, working to support the body, have not had time to cultivate their minds, but likewise those who, born in the lap of affluence, have never had their invention sharpened by a necessity – are, nine out of ten, the creatures of habit and impulse.

If I were not afraid to derange your nervous system by the bare mention of a metaphysical enquiry, I should observe, sir, that self-preservation is, literally speaking, the first law of nature, and that the care necessary to support and guard the body is the first step to unfold the mind and inspire a manly spirit of independence. The mewing babe in swaddling clothes, who is treated like a superior being, may perchance become a gentleman; but nature must have given him uncommon faculties if, when pleasure hangs on every bough, he has sufficient fortitude either to exercise his mind or body in order to acquire personal merit. The passions are necessary auxiliaries of reason: a present impulse pushes us forward, and when we discover that the game did not deserve the chase, we find that we have gone over much ground, and not only gained many new ideas, but a habit of thinking. The exercise of our faculties is the great end, though not the goal we had in view when we started with such eagerness.

It would be straying still further into metaphysics to add that this is one of the strongest arguments for the natural immortality of the soul. Everything looks like a means, nothing like an end, or point of rest, when we can say, now let us sit down and enjoy the present moment; our faculties and wishes are proportioned to the present scene; we may return without repining to our sister clod. And if no conscious dignity whisper that we are capable of relishing more refined pleasures, the thirst of truth appears to be allayed; and thought, the faint type of an immaterial energy, no longer bounding it knows not where, is confined to the tenement that affords it sufficient variety. The rich man may then thank his God that he is not like other men – but when is retribution to be made to the miserable, who cry day and night for help, and there is no one at hand to help them? And not only misery but immorality proceeds from this stretch of arbitrary authority. The vulgar have not the power of emptying their mind of the only ideas they imbibed whilst their hands were employed; they cannot quickly turn from one kind of life to another. Pressing them entirely unhinges their minds; they acquire new habits, and cannot return to their old occupations with their former readiness; consequently they fall into idleness, drunkenness and the whole train of vices which you stigmatise as gross.

A government that acts in this manner cannot be called a good parent, nor inspire natural (habitual is the proper word) affection in the breasts of children who are thus disregarded.

The game laws are almost as oppressive to the peasantry, as press warrants to the mechanic.* In this land of liberty what is to secure the property of the poor farmer when his noble landlord chooses to plant a decoy field* near his little property? Game devour the fruit of his labour, but fines and imprisonment await him if he dare to kill any – or lift up his hand to interrupt the pleasure of his lord. How many families have been plunged, in the sporting countries, into misery and vice for some paltry transgression of these coercive laws, by the natural consequence of that anger which a man feels when he sees the reward of his industry laid waste by unfeeling luxury? When his children’s bread is given to dogs!

You have shown, sir, by your silence on these subjects, that your respect for rank has swallowed up the common feelings of humanity; you seem to consider the poor as only the livestock of an estate, the feather of hereditary nobility. When you had so little respect for the silent majority of misery, I am not surprised at your manner of treating an individual whose brow a mitre will never grace, and whose popularity may have wounded your vanity – for vanity is ever sore. Even in France, sir, before the revolution, literary celebrity procured a man the treatment of a gentleman; but you are going back for your credentials of politeness to more distant times. Gothic affability is the mode you think proper to adopt, the condescension of a baron, not the civility of a liberal man. Politeness is, indeed, the only substitute for humanity; or what distinguishes the civilised man from the unlettered savage? And he who is not governed by reason should square his behaviour by an arbitrary standard; but by what rule your attack on Dr Price was regulated* we have yet to learn.

I agree with you, sir, that the pulpit is not the place for political discussions,* though it might be more excusable to enter on such a subject when the day was set apart merely to commemorate a political revolution and no stated duty was encroached upon. I will, however, waive this point, and allow that Dr Price’s zeal may have carried him further than sound reason can justify. I do also most cordially coincide with you that till we can see the remote consequences of things, present calamities must appear in the ugly form of evil, and excite our commiseration. The good that time slowly educes from them may be hid from mortal eye, or dimly seen, whilst sympathy compels man to feel for man, and almost restrains the hand that would amputate a limb to save the whole body. But, after making this concession, allow me to expostulate with you, and calmly hold up the glass which will show you your partial feelings.

In reprobating Dr Price’s opinions you might have spared the man; and if you had had but half as much reverence for the grey hairs of virtue as for the accidental distinctions of rank, you would not have treated with such indecent familiarity and supercilious contempt a member of the community whose talents and modest virtues place him high in the scale of moral excellence. I am not accustomed to look up with vulgar awe, even when mental superiority exalts a man above his fellows; but still the sight of a man whose habits are fixed by piety and reason, and whose virtues are consolidated into goodness, commands my homage – and I should touch his errors with a tender hand when I made a parade of my sensibility. Granting, for a moment, that Dr Price’s political opinions are utopian reveries, and that the world is not yet sufficiently civilised to adopt such a sublime system of morality, they could, however, only be the reveries of a benevolent mind. Tottering on the verge of the grave, that worthy man in his whole life never dreamed of struggling for power or riches; and, if a glimpse of the glad dawn of liberty rekindled the fire of youth in his veins, you, who could not stand the fascinating glance of a great lady’s eyes,* when neither virtue nor sense beamed in them, might have pardoned his unseemly transport – if such it must be deemed.

I could almost fancy that I now see this respectable old man in his pulpit,* with hands clasped and eyes devoutly fixed, praying with all the simple energy of unaffected piety; or, when more erect, inculcating the dignity of virtue, and enforcing the doctrines his life adorns; benevolence animated each feature, and persuasion attuned his accents; the preacher grew eloquent, who only laboured to be clear; and the respect that he extorted seemed only the respect due to personified virtue and matured wisdom. Is this the man you brand with so many opprobrious epithets? He whose private life will stand the test of the strictest enquiry – away with such unmanly sarcasms and puerile conceits. But, before I close this part of my animadversions, I must convict you of wilful misrepresentation and wanton abuse.

Dr Price, when he reasons on the necessity of men attending some place of public worship, concisely obviates an objection that has been made in the form of an apology,* by advising those who do not approve of our liturgy, and cannot find any mode of worship out of the church in which they can conscientiously join, to establish one for themselves. This plain advice you have tortured into a very different meaning, and represented the preacher as actuated by a Dissenting frenzy, recommending Dissensions ‘not to diffuse truth, but to spread contradictions’.14* A simple question will silence this impertinent declamation – what is truth? A few fundamental truths meet the first enquiry of reason, and appear as clear to an unwarped mind as that air and bread are necessary to enable the body to fulfil its vital functions; but the opinions which men discuss with so much heat must be simplified and brought back to first principles; or who can discriminate the vagaries of the imagination, or scrupulosity of weakness, from the verdict of reason? Let all these points be demonstrated, and not determined by arbitrary authority and dark traditions, lest a dangerous supineness should take place; for probably, in ceasing to enquire, our reason would remain dormant, and delivered up without a curb to every impulse of passion, we might soon lose sight of the clear light which the exercise of our understanding no longer kept alive. To argue from experience, it should seem as if the human mind, averse to thought, could only be opened by necessity; for, when it can take opinions on trust, it gladly lets the spirit lie quiet in its gross tenement. Perhaps the most improving exercise of the mind, confining the argument to the enlargement of the understanding, is the restless enquiries that hover on the boundary, or stretch over the dark abyss of uncertainty. These lively conjectures are the breezes that preserve the still lake from stagnating. We should be aware of confining all moral excellence to one channel, however capacious; or, if we are so narrow-minded, we should not forget how much we owe to chance that our inheritance was not Mahometism, and that the iron hand of destiny, in the shape of deeply rooted authority, has not suspended the sword of destruction over our heads. But to return to the misrepresentation.

Blackstone,15 to whom Mr Burke pays great deference, seems to agree with Dr Price that the succession of the King of Great Britain depends on the choice of the people, or that they have a power to cut it off; but this power, as you have fully proved, has been cautiously exerted, and might with more propriety be termed a right than a power. Be it so! Yet when you elaborately cited precedents to show that our forefathers paid great respect to hereditary claims, you might have gone back to your favourite epoch, and shown their respect for a church that fulminating laws have since loaded with opprobrium. The preponderance of inconsistencies, when weighed with precedents, should lessen the most bigoted veneration for antiquity, and force men of the eighteenth century to acknowledge that our canonised forefathers were unable, or afraid, to revert to reason without resting on the crutch of authority; and should not be brought as a proof that their children are never to be allowed to walk alone.

When we doubt the infallible wisdom of our ancestors, it is only advancing on the same ground to doubt the sincerity of the law, and the propriety of that servile appellation – our sovereign Lord the King.* Who were the dictators of this adulatory language of the law? Were they not courtly parasites and worldly priests? Besides, whoever at divine service, whose feelings were not deadened by habit, or their understandings quiescent, ever repeated without horror the same epithets applied to a man and his Creator? If this is confused jargon – say what are the dictates of sober reason or the criterion to distinguish nonsense?

You further sarcastically animadvert on the consistency of the democratists by wresting the obvious meaning of a common phrase, the dregs of the people;* or your contempt for poverty may have led you into an error. Be that as it may, an unprejudiced man would have directly perceived the single sense of the word, and an old Member of Parliament could scarcely have missed it. He who had so often felt the pulse of the electors needed not have gone beyond his own experience to discover that the dregs alluded to were the vicious, and not the lower class of the community.