7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

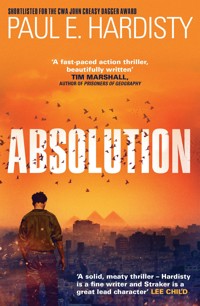

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Claymore Straker

- Sprache: Englisch

When vigilante justice-seeker Claymore Straker is witness to the murders of a family he has befriended, and his lover's husband and son disappear, his investigations take him to the darkest places he could ever have imagined … The stunning fourth instalment in the critically acclaimed Claymore Straker series. 'A stormer of a thriller – vividly written, utterly tropical, totally gripping' Peter James 'A fast-paced action thriller, beautifully written' Tim Marshall, author of Prisoners of Geography 'Hardisty is a fine writer and Straker is a great lead character' Lee Child _____________________ It's 1997, and eight months since vigilante justice-seeker Claymore Straker fled South Africa after his explosive testimony to Desmond Tutu's Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In Paris, Rania LaTour, Claymore's former lover, comes home to find that her son and her husband, a celebrated human rights lawyer, have disappeared. On an isolated island off the coast of East Africa, the family that Clay has befriended is murdered as he watches. So begins the fourth instalment in the Claymore Straker series, a breakneck journey through the darkest reaches of the human soul, as Clay and Rania fight to uncover the mystery behind the disappearances and murders, and find those responsible. At times brutal, often lyrical, but always gripping, Absolution is a thriller that will leave you breathless and questioning the very basis of how we live and why we love. ____________________ Praise for Paul E. Hardisty 'A trenchant and engaging thriller that unravels this mysterious land in cool, precise sentences' Stav Sherez, Catholic Herald 'This is a remarkably well-written, sophisticated novel in which the people and places, as well as frequent scenes of violent action, all come alive on the page...' Literary Review 'Gripping and exciting … the quality of Hardisty's writing and the underlying truth of his plots sets this above many other thrillers' West Australian 'Searing … at times achieves the level of genuine poetry' Publishers Weekly 'Beautifully written, blisteringly authentic, heart-stoppingly tense and unusually moving' Paul Johnston 'The plot burns through petrol, with multiple twists and turns' Vicky Newham

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 525

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Absolution

PAUL E. HARDISTY

For Heidi

‘And God has created you, and in time will cause you to die’

Holy Qu’ran, Surah 16:70

‘It would kill the past, and when that was dead, he would be free’

Oscar Wilde

ABSOLUTION

Glossary

ANC – African National Congress; formed first legitimately elected democratic government of South Africa

Bakkie – Afrikaans slang: pick-up truck

Bokkie – Afrikaans slang: beautiful woman

Bossies – Afrikaans slang: bush dementia

Bliksem – Afrikaans slang: bastard

China – Rhodesian slang: friend

DGSE – Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure: French intelligence agency

Doffs – Afrikaans slang: idiots.

Glide – Rhodesian slang: trip

Lekker – Afrikaans slang: nice, sweet

Okes – Afrikaans slang: guy

Oom – Afrikaans slang: uncle (word of respect)

Ooma – Afrikaans slang: aunty, old woman, grandmother (word of respect)

Parabat – Army slang: South African paratrooper; also vliesbom (meat bomb)

Operation COAST – Apartheid South Africa’s super-secret chemical and biological weapons programme

Poppie – Afrikaans slang: doll

R4 – standard issue 5.56 mm calibre assault rifle of South African Army, the South African-made version of the Israeli Galil rifle, semi-automatic

Rofie – Afrikaans slang: new recruit

Rondfok – Afrikaans slang: literally ‘circle fuck’

RV – rendezvous point

SADF – South African Defence Forces

Seun – Afrikaans: son

Sitrep – situation report

SWAPO – South West Africa People’s Organisation; rebel group fighting for Namibian independence

Torch Commando – banned underground organisation of mostly white South Africans dedicated to overthrowing apartheid

TRC – South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, chaired by Desmond Tutu, started in 1996 to help heal the wounds after apartheid

Valk – Afrikaans for hawk, the designation for a platoon of South African Army paratroopers, approximately thirty men

Volkstaat – Afrikaans for the dreamed-of independent Afrikaner homeland

Vrot – Afrikaans slang: wasted, intoxicated

Zut – Rhodesian slang: nothing

Part I

25th October 1997. Paris, France. 02:50 hrs

Chéri, mon amour:

My husband has disappeared. And so has my son.

As I write this, my tears stain the page. How many have I wept onto these pages in the three and half years since you and I first met? Has it really been that long? It is as if I have known you forever, and not at all.

I am frantic. I can feel the panic churning in my breast. It has been two days since I discovered that they were gone. God, help me, please.

I wish you were here.

It was a Tuesday. A normal day. We got up, had breakfast at the usual time. I got Eugène ready for the day. Hamid left for the office as he always does, taking Eugène with him to drop him at the crèche.

I replay that morning in my mind, trying to identify something – anything – that might have been different, out of the ordinary. Something that may give me some clue. The coffee and bread on the table; Eugène in his high chair attempting to spoon puréed vegetables into his beautiful little mouth; the radio playing in the background – Radio Nationale, something about the international chemical weapons treaty coming into force. Hamid is dressed in his favourite suit with the silk tie I gave him for his birthday last year – the grey one that sets off the silver that has begun to fleck his temples. I wanted to make love with him that morning, but he was in a hurry – a big case he is working on – so he kissed me, rolled out of bed and got into the shower.

As usual on Tuesdays, I went to the bureau. I worked on my latest piece – child slavery in the Philippines. I was a little late coming home. I usually return by two o’clock so that I have plenty of time to start dinner and welcome my husband and son when they get home, which is normally at about three o’clock. That day I didn’t arrive until just before three. Hamid and Eugène weren’t home yet, so I started preparing the vegetables, marinating the filet. By half past three, they still had not arrived. Hamid is fastidiously punctual – always calls if he is going to be late. I waited another quarter of an hour and then tried his mobile. He did not answer. I left a voice message. At a quarter past four I tried again. Still no answer. I called his office. His executive assistant told me that he hadn’t been in the office all day. I sat, stunned.

I waited, told myself that it would all be fine, that the rising panic I was feeling was ridiculous, that there was some logical explanation, and that very soon the door would open and my husband and son would be there, smiling at me.

The hours crept by. I drank cup after cup of coffee. I telephoned everyone I could think of that might know where they could be: Hamid’s sister in Toulon, his law partner, our family doctor, all of the other mothers that I know from the crèche. Later that evening, I even called Hamid’s mother in Beirut. No one knew anything. That night I did not sleep at all.

Yesterday, I went to the crèche first thing in the morning, as soon as it opened. The manageress confirmed that Hamid had dropped Eugène off on Tuesday morning, as usual. She showed me the registration records. Hamid’s signature was there, very clearly. The time was 08:25. This is part of our arrangement, how we have decided to run our life together. Three days a week, Hamid takes Eugène to the crèche on his way to work in the morning, and then collects him again at half past two and brings him home. We eat an early supper together as a family, and then Hamid goes back to the office, or works in his study at home. This allows me to go directly to the bureau three mornings a week. I catch the bus and the metro. It means we only need one car. On Thursdays and Fridays, I work from home, and we both try to spend the weekends together, and avoid work for a time. We are a very modern Muslim family, and for that I am grateful. It means I have been able continue my career.

Our life, I thought, all considered, was good. Happy. I still cannot believe they are gone. I look around the room, smelling them both, feeling their presence in every object, expecting at any moment to hear the echo of their footsteps on the parquet floor, see their smiling faces peering around the doorframe.

I met Hamid not long after I returned from Cyprus after losing the baby. Our baby, chéri. I was still damaged and withdrawn after everything that had happened – the time in Istanbul with you, then Cyprus and the minefield, the explosion … the miscarriage. Hamid was thoughtful and patient, sending me flowers and listening to my stories, and when he asked me to marry him we still had not slept with each other. In fact, during our three-month courtship, all he ever tried to do was kiss me. He was very respectful, a perfect gentleman. We were married in spring, in the countryside in Normandie, and Eugène was born a year later, healthy and strong and holding his head up in the first month. Every time I look at him I wonder what might have been.

I have never told you any of this, I know. Those two letters you sent me from prison in Cyprus still lie in my bureau, read and reread … but unanswered. Only here, in these pages, have I shared my life with you. Any other way would have been too hurtful – for us both.

It has been just over two years now since Hamid and I married, and Claymore, I want you to know that he has been a good husband. He treats me well and is never disrespectful. He works long hours, and over the past year he has had to travel quite frequently for work, mostly to meet with clients he is defending. I miss him when he goes, but I have not had any reason to worry, to think he might be unfaithful. Not until recently. He is a gentle man, quietly talkative yet considered. Delicate, in a way. Everything that you are not.

Hamid is a good Muslim – better in many ways than I am. But his faith is not overt. As with everything he does, his piety is quiet and understated and thoroughly planned. He goes to the mosque on Fridays, occasionally, if he can get away from work, but otherwise I have never seen him praying at home or anywhere else. He does not smoke or drink, and I have not seen him lose his temper or raise his voice since we have been together. Above all, he is open and communicative in a way you never were, and probably never can be, wherever you are, Allah protect you.

Perhaps Hamid has taken Eugène to the country. Maybe he just needed a break, some time to himself. I know he has been under a lot of stress recently. This latest case in Egypt has been very difficult for him. He has not told me much about it – he never does, but a wife knows these things. This is what I tell myself. That I know. That everything will be alright. That, despite two days of silence, he will pick up the phone and call me. Now. Now.

Now.

He must know that I am worried beyond sickness. Yes, he would know. The only reason he hasn’t called is that he cannot. Something must have happened to them on the way home. Mon Dieu, I cannot bear to think of it.

And yet, I have telephoned every hospital in Paris. No one bearing the name Hamid or Eugène Al Farouk has been registered anywhere. I called the police, of course, and completed a missing person’s report, but have heard nothing back yet. It is as if they have vanished. As if they have been erased from the surface of the Earth.

I need to sleep now. I can barely see the page. I have cried myself out. And I realise that without them – without you – I have no one.

I am completely alone.

* 1 *

Guns and Money

26th October 1997

Latitude 6° 21' S; Longitude 39° 13' E,

Off the Coast of Zanzibar, East Africa

Claymore Straker drifted on the surface, stared down into the living architecture of the reef and tried not to think of her. Prisms of light crazed the many-branched and plated corals, winked rainbows from the scales of fish. Edged shadows twitched across the shoals, and for a moment dusk came, muting the colours of the sea. Floating in this new darkness, a distant echo came, hard and metallic, like the first syllables of a warning. Clay shivered, felt the cold do a random walk up his spine, seep into the big muscles across his back. He listened awhile, but as quickly as it had come, the sound was gone.

Clay blew clear his snorkel, pulled up his mask, and looked out across the rising afternoon chop, searching the horizon. Other than the weekly supply run from Stone Town, boats here were few. It was off-season and the hotel – the only establishment on the island – was closed. He could see the long arc of the island’s southern point, the terrace of the little hotel where Grace worked as caretaker, the small dock where guests were welcomed from the main island, and away on the horizon, a dark wall of rain-heavy cloud, moving fast in a freshening easterly. He treaded water, scanned the distance back toward the mainland. But all he could see were the great banks of cloud racing slantwise across the channel and the sunlight strobing over the world in thick stochastic beams, everything transient and without reference.

He’d lost track of how long he’d been here now. Long enough to fashion a sturdy mooring for Flame from a concrete block that he’d anchored carefully on the seabed. Long enough to have snorkelled every part of the island’s coastline, to know the stark difference between the life on the protected park side, and the grey sterility of the unprotected, fished-out eastern side. Sufficient time to hope that, perhaps, finally, he had disappeared.

The sun came, fell warm on the wet skin of his face and shoulders and the crown of his head. He pulled on his mask, jawed the snorkel’s mouthpiece and started towards the isthmus with big overhand strokes. Months at sea had left him lean, on the edge of hunger, darkened and bleached both so that the hair on his chest and arms and shorn across the bonework of his skull stood pale against his skin. For the first time in a long time, he was without pain. He felt strong. It was as if the trade winds had somehow cleansed him, helped to heal the scars.

As he rounded the isthmus, Flame came into view. She lay bow to the island’s western shore, straining on her mooring. He could just see the little house where Grace lived, notched into the rock on the lee side of the point, shaded by wind-bent palms and scrub acacia.

And then he heard it again.

It wasn’t the storm. Nor was it the sound of the waves pounding the windward shore. Its rhythm was far too contained, focused in a way nature could never be. And it was getting louder.

A small boat had just rounded the island’s southern point and was heading towards the isthmus. The craft was sleek, sat low in the water. Spray flew from its bow, shot high from its stern. It was some kind of jet boat – unusual in these waters, and moving fast. The boat made a wide arc, steering clear of the unmarked shoals that dangered the south end of the island, and then abruptly changed course. It was heading straight for Flame. Whoever was piloting the thing knew these waters, and was in a hell of hurry.

Clay floated low and still in the water, and watched the boat approach. It was close enough now that he could make out the craft’s line, the black stripe along the yellow hull, the long, narrow bow, the raked V of the low-swept windscreen. It was closing on Flame, coming at speed. Two black men were aboard, one standing at the controls, the other sitting further back near the engines. The man who was piloting wore sunglasses and a red shirt with sleeves cut off at heavily muscled shoulders. The other had long dreadlocks that flew in the wind.

Twenty metres short of Flame, Red Shirt cut power. The boat slowed, rose up on its own wake and settled into the water. Dreadlock jumped up onto the bow with a line, grabbed Flame’s portside mainstay and stepped aboard.

Clay’s heart rate skyed. He floated quiet in the water, his heart hammering inside his ribs and echoing back against the water. Dreadlock tied the boat alongside and stepped into Flame’s cockpit. He leaned forwards at the waist and put his ear to the hatch a moment, then he straightened and knocked as one would on the door of an apartment or an office. He waited a while, then looked back at the man in the jet boat and hunched his shoulders.

‘Take a look,’ came Red Shirt’s voice, skipping along the water, the local accent clear and unmistakable.

Dreadlock pushed back the hatch – Clay never kept it locked – and disappeared below deck. Perhaps they were looking for someone else. They could be just common brigands, out for whatever they could find. All of Clay’s valuables – his cash and passports – were in the priest hole. His weapons, too. It was very unlikely that the man would find it, so beautifully concealed and constructed was it. There was nothing else on board that could identify Clay in any way. Maybe they would just sniff around and leave.

Nine months ago, he’d left Mozambique and made his way north along the African coast. Well provisioned, he’d stayed well offshore and lived off the ocean for weeks at a time – venturing into harbour towns or quiet fishing villages for water and supplies only when absolutely necessary, keeping clear of the main centres, paying cash, keeping a low profile, never staying anywhere long. He had no phone, no credit cards, and hadn’t been asked to produce identification of any sort since he’d left Maputo. Then he’d come here. An isolated island off the coast of Zanzibar. He’d anchored in the little protected bay. A couple of days later Grace had rowed out in a dinghy to greet him, her eight-year-old son Joseph at the oars, her adolescent daughter in the stern, holding a basket of freshly baked bread. He decided to stay a few days. Grace offered him work doing odd jobs at the hotel – fixing a leaking pipe, repairing the planking on the dock, replacing the fuel pump on the generator. In return, she brought him meals from her kitchen, the occasional beer, cold from the fridge. He stayed a week, and then another. They became friends, and then, unintentionally, lovers. Nights he would sit in Flame’s darkened cockpit and look out across the water at the lamplight glowing in Grace’s windows, watch her shadow moving inside the house as she put her children to bed. One by one the lights would go out, and then he’d lie under the turning stars hoping sleep would come.

After a while, he’d realised that he’d stayed too long. He’d made to leave, rowed to shore and said goodbye. Joseph had cried. Zuz just smiled. But Grace had taken him by the hand and walked him along the beach and to the rocky northern point of the island where the sea spread blue and calm back towards the main island, and she’d convinced him to stay.

But now Clay shivered, watching Dreadlock move about the sailboat. The first drops of rain met the water, a carpet of interfering distortions.

‘Hali?’ shouted Red Shirt in Swahili from the jet boat. News?

‘No here,’ came the other man’s voice from below deck.

‘Is it his?’ said Red Shirt.

‘Don’t know.’

‘It looks like his.’

‘Don’t know.’

‘No guns? No money?’

‘Me say it. Nothing.’

‘Fuck.’

‘What we do?’

‘We find him. Let’s go.’

The jet boat’s engines coughed to life with a cloud of black smoke. Dreadlock untied the line, jumped back aboard and pushed off. The boat’s bow dipped with his weight, then righted. Clay dived, watched from below as the craft made a wide circle around Flame, buffeting her with its wake, then turned for shore.

It was heading straight for Grace’s house.

26th October 1997. Paris, France. 17:35 hrs

Still nothing.

Today I did something I have never done before. I went into my husband’s office and looked through his things. I went through all the papers on his desk, the bookshelves, the filing cabinet in which he keeps his personal financial records, some files from past cases. I had to pry open the lock on his desk drawer with a screwdriver and a hammer. The desk belonged to Hamid’s father and is made of French oak. When I hammered out the clasp, the blade of the screwdriver splintered the wood of the drawer frame and cracked one of the front panels. I must take it to be repaired before Hamid comes home. If he sees it he will know I was spying. When we were first married, we agreed to trust each other completely. I have violated that now. God knows if I ever found him going through my office; I would be more than furious.

Why am I feeling this? Under the circumstances, I am sure he would understand. It has been three days now, and still I have had no word from him.

The police have assigned a detective to the case – Assistant Detective Marchand; an agreeable young lady who seems very junior, but is undeniably bright and enthusiastic. She came to see me this morning and I gave her recent photos of both Hamid and Eugène. This afternoon she contacted me to confirm that no persons bearing their names or matching their descriptions have been admitted to any hospital in France, nor have they reported to or been brought into any police station in the country. Our silver Peugeot has not been seen anywhere. She called me just now to tell me that they have also finished checking all outgoing passenger records from all the major airports and ferry terminals in France, and have found nothing. She asked me if their passports were still in the house. She also asked me if my husband had been having an affair. I was shocked. I know I must have sounded shocked.

I found their French passports just now in the bottom drawer of Hamid’s desk, along with Eugène’s birth certificate and Hamid’s Lebanese passport. At least I know that Hamid had not planned to leave the country when he left for the office on Tuesday morning. This is a big relief to me. It should not be.

In the same drawer, I found the deed to a life insurance policy. I knew Hamid – meticulous person that he is – had taken out policies on both of us, right after Eugène was born. The policy on my life is relatively small. His policy is significant: over a million euros in the case of death, with me as the beneficiary. I also found twelve hundred US dollars in one-hundred-dollar notes, over three thousand euros in mixed denominations, and a stack of Egyptian pounds worth about six hundred euros. If he had been planning to go somewhere for any extended period, especially if he did not want to be found, he would have taken cash. Whatever happened, it was not premeditated.

I went through all the drawers in his desk looking for any signs of an affair. There was not a hint of feminine perfume – not even mine. There were no compromising photos or letters. I went through his bank statements looking for hotel or dinner charges, purchases from florists or jewellers or lingerie shops – any of the obvious things that he is intelligent enough to have avoided if he had been trying to hide something from me. I was shocked at the cost of the beautiful necklace he bought me for our anniversary, but it has only convinced me more that an affair is unlikely. Still, you never know these things. My aunt had been married to the same man for thirty years and then caught him being unfaithful with an older woman. The affair had been going on for more than three years.

There was another thing the young inspector asked me: Did my husband or I have any enemies? She had done her research. She was aware of the columns I wrote last year about South Africa’s apartheid-era chemical and biological weapons programme – the ones I based on the information you sent me from Mozambique last year; the ones that led to the arrest and indictment of the head of that programme on charges of murder, embezzlement and extortion. And she knew about my role in exposing the Medveds’ corrupt operations in Yemen and Cyprus before that. She knew about all the stories that built my reputation – the ones we worked on together, chéri.

This is part of being an investigative journalist, I told her. All of us in this profession must deal with the same threats, the social media bullying, the vilification, the accusations of bias and political motivation. As for my husband, he is a human rights lawyer, I said, I now regret, rather rudely. So what do you think? I added. Sometimes, I think I have started to speak as you do, Claymore.

The inspector looked at me with a patience that belied her years. She showed no sign of being offended. I told her that Hamid had been doing this work for a long time, and while there had been verbal attacks and legal injunctions, there had never been a time when he was physically threatened. Not that he had told me about, anyway.

Is there anything else, she asked me, anything at all that seemed strange or unusual? You would be surprised at how important the most seemingly innocuous observations can be in these cases.

No, I told her. Nothing else. Even as I was saying it I knew I was lying. Because there is something else. Of course, there is.

In the hours since Inspector Marchand left I have done nothing but pull apart and upend every detail of the last three days, until the whole of it has become nothing but a churned-up morass. And now, from this reduction, only the malaise remains. I cannot yet describe it, but I can no longer deny it. It has been with me for too long.

So, for now, here are the possibilities:

1) Hamid has decided he needs some time with his son, alone, and is ensconced somewhere in the countryside, in a Norman farmhouse or a villa on the Côte d’Azur – he has always loved those weekend getaway places. Perhaps the stress of the last few months has simply become too much. If so, why has he not called me? Does he think I would not understand?

2) Hamid has run off with another woman. He has been having a secret affair and has decided that he can no longer continue our relationship. Being the Muslim man he is, he cannot bear to live without his son, and believes in his heart that he has a prior and unalienable right to custody of his male heir. But if so, would he not by now have had the courage and compassion to inform me of his decision?

3) Hamid and Eugène have been in a car accident and are still undiscovered, perhaps down a steep embankment along a wooded country road. They are trapped or in pain, and are unable to walk to help. The reason for such a trip into the country may have been for reasons (1) or (2). If so, God help them, please. All is forgiven.

4) Hamid has left the country, has taken Eugène with him, and for any combination of the reasons above is unable or unwilling to contact me. Even though the police say they have not been through any of the major airports, he is a very experienced international traveller and there are many places he might have crossed the frontier unchecked. If so, why would Hamid have left behind their passports and all that cash? This makes no sense.

5) Hamid’s enemies have taken him and my son hostage, or worse. It sounds melodramatic even thinking it. But I know that his recent work has put him in direct confrontation with some powerful people in Egypt, including members of the government. He has been defending political prisoners accused of various crimes against the state, including Muslim activists. In January, he won a major victory – widely reported in the international news – which resulted in the release from prison of a high-profile environmental activist. Would the Egyptian government really resort to kidnapping a French citizen from his own home? I find this highly implausible. But if it is true, why no ransom demand? Unless of course, they have simply been murdered. God protect them and forgive me for even thinking it.

6) Hamid and Eugène have been kidnapped or killed by our enemies – yours and mine, mon chéri. I can barely bring myself to write the words. Regina and Rex Medved are dead, their empire fragmented and dispersed. Whoever has picked up the pieces should be thanking us. Chrisostomedes, the bastard, has been politically disgraced and ruined financially. He is certainly spiteful enough, and kidnapping is his style, but I simply cannot believe that he would erode his remaining resources on a vendetta against me. He has many far more dangerous enemies. With people like him, however, you never know. The white supremacists of the South African Broederbond are a possibility. The last time I spoke to you, a little over nine months ago, you had just testified to Desmond Tutu’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, where you revealed the full horror of the atrocities committed by Operation COAST during apartheid. I remember every word of our too brief telephone conversation. You were convinced that the Broederbond were hunting you down to exact revenge for this – and because of what you knew and had not yet revealed. That is why you sent me the information – the photographs and the notebook. I promised you I would write the story, Claymore, and I did. I hope you know, wherever you are, that I kept my word.

I am just a reporter, and there are many others who have written about COAST’s activities since. So it does not seem plausible or logical that they would single me out. They cannot silence us all. And if they wanted to stop me writing about them, why not just threaten me, or kill me? And I have heard nothing since Hamid and Eugène disappeared – no demands, no threats. If anything has happened to them – it hurts just to write their names – because of something I have done, I will never forgive myself.

7) Hamid knows he is in danger (from his enemies or mine), and has disappeared, perhaps to protect me. That is the kind of person he is: principled, self-sacrificing. But if this is the case, why would he take our son, and why did he not trust me to help him? He knows that I have experience and training in these matters and that I would be an asset to him. Why would he not confide in me? Together we are stronger.

None of this analysis helps in the least.

Please God, if you must take someone, take me.

21:45 hrs

Inspector Marchand has just telephoned. They have found something. She will not tell me what it is over the phone. I am to meet her at the police station tomorrow morning at eight. I have not slept for seventy-two hours. My heart is racing. I am going to take a sedative.

* 2 *

The Only Constant in Life

Of course, it was the ultimate indulgence. Friends, lovers, family, people you cared for. They tied you down, kept you dependent, made you vulnerable. And worse, they paid for their friendship with vulnerability. When someone wants to hurt you, they target those you love most.

There was no time to swim back to Flame. Grace’s house was a good three hundred metres along the shore. The jet boat was almost there now, slowing in the shallow water of the cove. Clay turned and made a straight line for the rocks of the isthmus, swimming hard. At the water’s edge, he pulled off his fins, mask and snorkel, and started barefoot through the rocks, breathing hard.

Red Shirt killed the engine and the boat drifted towards the little white beach in front of Grace’s house. Clay upped his pace, sprinting now along the sand footpath that skirted the tree line. A sheet of rain swept across the island. He could hear Red Shirt and Dreadlock talking as they waded from the boat, gained the beach and started up the rock-edged pathway to the house, still apparently unaware of his presence. Red Shirt knocked on the door.

At this time of day, Grace would still be at work, the children hunched over home-school lessons in the empty restaurant. Clay decided to keep to the trees, approach the house from the landward side, try to observe the intruders from close range. Rain sluiced from the palms, sheeted across the bay. He slowed, staying hidden. Red Shirt stood at the front door, knocked again. The door opened. Little Joseph, in shorts and a Manchester United t-shirt, stood in the doorway. Clay snatched a breath, stopped dead.

He could hear Red Shirt speaking to the boy, then Joseph calling for his mother. But before she could come to the door, Red Shirt grabbed the boy by the hand, spun him around and put a knife to his neck.

Clay’s heart lurched. From inside the house now, the sound of Grace screaming. Red Shirt kicked the door aside and disappeared inside. Dreadlock followed him, pulling a fighting knife from under his shirt.

Clay didn’t have a choice. There was no time. He ran straight for the front door, burst in.

The place wasn’t big. A sitting room at the front with a big couch and a little TV on a stand, a table by the door with an old-style rotary telephone on it – one of only two on the island. A doorway out back led to the kitchen and the children’s room. Clay stood in the doorway, dripping in his swimming shorts, unarmed. Red Shirt stood with Joseph clutched to his chest, the knife’s blade poised against the dark skin of the boy’s throat. A drop of blood kissed the steel. Grace was kneeling on the floor, tears in her eyes, her lower lip cracked and bleeding, her hands raised in supplication. Dreadlock stood above her, hand raised.

Both men turned to face him, what-the? expressions on their faces.

‘Looking for me, gents?’ said Clay.

‘It’s him,’ blurted Dreadlock, glancing at Clay’s stump.

‘Ja, it’s me,’ said Clay, raising his open hand, and stepping towards Red Shirt and the boy. ‘So how about we just talk about this. No need for any trouble.’

‘Oh, no trouble, baas,’ said Red Shirt, a grin cutting his face.

‘Give me the boy,’ said Clay, ‘and we can talk.’

‘Oh, but we don’t want to talk,’ said Red Shirt. ‘We here to deliver a message.’

Clay was within a long pace of Red Shirt and Joseph now. Dreadlock had moved away from Grace and was circling in towards Clay, crouching low, brandishing the knife in a right-handed dagger grip. Clay had a pretty good idea what the message was.

He had learned, many years before, that the only way to win is to take the initiative and keep it. Hit first, hit hard. That’s what Crowbar – his platoon leader during the war in Angola – had drilled into them from the first day of jump school. Later, in prison in Cyprus, it had kept him alive. Red Shirt was closer, but Joseph was vulnerable. The slightest mistake and the boy’s throat would be opened. Dreadlock was coming at Clay from the side. Red Shirt was looking at his partner, trying to communicate to him with his eyes.

Clay laughed, forced it out. ‘Why don’t you just tell him what you want him to do?’ he said, pushing a smile across his face. ‘Go ahead. I won’t listen.’

The two men sent perplexed glances at each other.

It was enough. Clay pivoted and burst low and to his left, caught Dreadlock’s knife arm in a vicious cross-body hammer blow, wrapping the stunned arm with his, and following a quarter-second later with a back-handed hammer fist to Dreadlock’s jaw. He felt the bone go, heard Dreadlock grunt and go slack. Then he stepped left, thrust out his hip and slammed Dreadlock to the floor, holding the outstretched knife arm as a pivot. Dreadlock tried to roll away, still clutching the knife, but Clay brought his left shin down onto the man’s head and leaned in, pinning him to the floor. Dreadlock grunted as his broken jaw deformed further. Then Clay slammed the back of Dreadlock’s straightened arm down across his knee. Dreadlock screamed in agony as his arm broke. Clay let the shattered limb fall to the floor, grabbed the knife, and twisted back upright. As he did he brought his right boot heel down hard onto Dreadlock’s outstretched knee.

It had all taken less than three seconds. Dreadlock lay whimpering on the floor. By now, Grace had managed to crawl away into the kitchen.

‘Now,’ said Clay, facing up to Red Shirt. ‘I’ll tell you what. You let the boy go, and you can deliver that message of yours. What do you say?’

Red Shirt was backing away now, towards the kitchen, his knife still at the boy’s throat. He looked scared.

Clay let Dreadlock’s knife clatter to the floor. ‘Look,’ he said, kicking it away. ‘I won’t hurt you. I know you’re doing this for someone. Whatever he’s paying you, I can pay you a lot more. I have cash, gold if you want it, out on the boat. Name your price. Please, just let the boy go.’

Red Shirt’s eyes widened, considering this perhaps. ‘How much?’

Rain hammered the roof.

‘Whatever you want,’ said Clay. ‘Name it. A hundred thousand?’

Red Shirt’s eyes widened. ‘Dollars?’ he said.

Clay nodded. ‘American.’

‘Cash?’

‘If that’s what you want.’

Red Shirt’s mouth opened, as if he was about to speak. Just then, Grace emerged from the kitchen. Blood dripped from her chin onto her white uniform. She held a tyre iron in one hand. Before Clay could move, she stepped up behind Red Shirt and swung at him with both hands. She was a strong woman, but Red Shirt was quick, and a lot bigger. In one movement, he flung the boy away to the floor, twisted and parried the blow with a forearm to the back of her raised elbow. The iron glanced off the side of his head just as he drove his blade into her body.

Grace staggered back into the wall, the knife buried in her chest, a look of disbelief on her face. Joseph was on the floor, his hands wrapped around his neck. Blood streamed from between his fingers. A constricted gurgle emerged from his throat. Red Shirt grabbed the tire iron, charged towards the door, swinging wildly. Clay ducked, let him go, moved to the boy.

He pushed the boy’s hands from the wound. The knife had gone deep, sliced through the oesophagus, the carotid artery. The opened cartilage glistened white. Blood pulsed. He’d seen wounds like this before – during the war, and since. He knew there was nothing he could do. He went to Grace. She was sitting with her back to the wall, breathing hard, holding the knife handle between her hands. Blood covered the front of her white uniform. The blade had gone in between two ribs, penetrated deep.

He had a full medical kit on Flame, but there wasn’t time to get it. He ran to the kitchen, flung open drawers and cupboards, scattering the contents, searching for anything he could use to staunch the bleeding. Outside, the roar of the jet boat starting, backing away. He grabbed a couple of towels, ran back to Grace. She was still breathing. He wrapped the towels around the knife, left the weapon in place. He had to get her to a hospital. The nearest was in Stone Town. At full speed with Flame’s little diesel engine, two hours away.

She reached her hand to his face. ‘Joseph,’ she said, a whisper.

Clay closed his eyes.

‘Why?’ she said. Blood frothed from her mouth. Tears streamed from her eyes.

What answer was there? What could he tell a dying woman who’d just witnessed her own son’s murder? What explanation, for any of it? Should he tell her that it was his fault, that they’d simply been caught in one of death’s coincidences, those random tragedies that seemed the only constant in life. Would it help her to know, in these last few moments, that the minute she’d befriended him, she had inadvertently increased the probability of her own demise a hundredfold, a thousand, and that the longer he’d stayed, the worse her chances had become. And now that her son lay dying at her feet, was there any point in telling her how sorry he was – for being so self-indulgent, for allowing himself the luxury of a connection with another human being, for letting some warmth into his life?

‘I’m sorry,’ was all he could say. Tears blurred his vision. He wiped them away, secured the towels, tried to help her up. He would try to get her to hospital. Even though he knew she would be dead in minutes, he would try. What else was there? Just sit there and let her go, passive, accepting of fate? He would try. That was all life was: a futile and inevitably unsuccessful battle against death.

She moaned, hung limp in his arms. Her eyes were closed.

He swung her into his arms. ‘Here we go, Grace,’ he said, starting for the door.

Joseph lay open-eyed in a pool of blood, the afternoon sun slanting across the hardwood floor, across his motionless body. Dreadlock groaned nearby. Clay stopped, looked down at the man, Grace heavy in his arms. She’d stopped breathing. He lay her down, put his mouth to hers and inflated her lungs. Blood filled his mouth. He spat, tried again. Her lungs were flooded. He touched her neck, felt for a pulse. She was gone.

Clay slumped to the floor. He sat there a long time, eyes closed, his mind blank as a starless desert night.

Dreadlock’s groans brought him back. The man was dragging himself towards the door, unable to stand, pushing himself along with his one good leg, his shattered arm hanging limp.

Clay stood, picked up Dreadlock’s knife, crouched beside him, ran the blade across the guy’s face. ‘Tell me everything,’ he said, ‘and I won’t cut your throat.’

Dreadlock stared up at him, wading through the pain.

Clay pushed the point of the blade into his neck. Blood welled up around the steel. ‘Now.’

‘Contract,’ Dreadlock blurted. ‘Some baas from the mainland. Give we two grand, US. Come here kill you. Two more we bring you body living.’

‘How did they know I was here?’

‘Me no know. He no say much.’

‘Who was he? Where was he from?’

‘White man. White African. No name.’

Clay swore. ‘Where is he now?’

‘Some rich hotel out de’ Stone Town.’

‘And your friend. What’s his name?’

The man shook his head, closed his eyes. Clay pushed the knife in.

Dreadlock yelped. ‘They call him name Big J.’

Clay pulled back the knife, wiped the blood on his shorts. As he did, he heard a gasp. It had come from behind the couch. Clay stood, listened. A moment later, another gasp, a sob.

‘Zuz,’ he said. ‘Is that you, sweetie?’

The girl emerged from behind the couch. She stood surveying the scene, eyes strained wide, her mouth hanging open as if in mid-scream. He could see the deep red of her tongue and the white of her lower teeth and the rictus black of her throat. She was shaking.

‘Zuz,’ he said. ‘Close your eyes, sweetheart. Don’t look.’

The girl did as she was told.

Clay crouched back down next to Dreadlock, looked into the man’s eyes. He placed the point of the knife’s blade over the man’s heart. Rain thundered on the sheet-metal roof.

Dreadlock stared up at him, shaking his head from side to side. ‘Please,’ he gasped. ‘I never hurt no one.’

27th October 1997. Paris, France. 12:30 hrs

I spent all morning with Inspector Marchand. She took me to an industrial estate on the outskirts of the city, near Crétail. We sat in her car and looked out through the rain-blurred windows at the charred remains of an automobile. It had been driven into the yard at night and set alight. She said that the engine block registration plate had been filed clean and the number plates removed. Everything inside the car had been incinerated. It was, I already knew, a professional job.

Then she passed me something. It was a piece of paper, a grocery-store receipt. Read it, she said. I did. Where did you find this? I asked her. And what does this have to do with the car? But I already knew. She had found it yesterday, not far from the car. Two litres of milk, a kilo of coffee beans, some asparagus, yoghurt. It was from our local store and was dated five days ago. It was my receipt. And that, out there, was what was left of our silver Peugeot 406.

There were no bodies in the car, she said. But not far away we found this. She passed me a sealed plastic evidence bag. Do you recognise it? I turned the bag over and over in my hands, not believing what I was seeing. It was one of Eugène’s t-shirts, the one with the little Canadian beavers on the front. Hamid brought it back from Montreal for him last year. I could not speak. I just sat there staring at the shirt, at the brown stains across the neck and sleeve. That is blood, she said.

And there was this, not far away, she said, handing me another evidence bag. It was the jacket from Hamid’s blue suit. It was torn at the shoulder and chest, stained with dirt and blood. We are going to test the blood from both items, she said. DNA evidence can be very useful in these cases.

We drove back to the police station in silence. When we arrived, we went to a small café nearby and had a coffee together. Inspector Marchand was suitably respectful and sympathetic, treating me as a friend would in such a situation. Then she started asking me about Hamid and our relationship. She was very adept, but I cannot help feeling that she knows more than she appears to. Does she know about my past, about the person I once was? Perhaps she is testing me. The questions came.

Had Hamid and I been having problems?

Everyone has problems, I replied, letting my irritation show, knowing where she was taking this.

Had we fought recently, argued – about Eugène perhaps?

No, I replied. No more than usual.

And then sharply, did I own a gun?

No, I said. I do not. I hate guns.

Have you been trained in the use of guns or other weapons? she asked.

No, I replied.

It was only partially a lie. I was trained, but as you know, Claymore, I was never very good with weapons, and I always despised them. The only time I was ordered to kill someone, in Yemen in 1994, I failed. You were there. You saw it. And in the end, of course, I was glad that I failed. I was an observer, a researcher, an analyst, not a field agent. The Directorate was never the right place for me. I know that now. Leaving and becoming a proper journalist (not just using it as a cover) was one of the best things I ever did.

One of them.

Inspector Marchand ruminated on this a while, sipped her coffee, glanced out into the street one too many times. Then finally, she came out with it.

We haven’t found any bodies, she said, but we are treating this as a murder investigation. Where was I on the day Hamid and Eugène disappeared?

23:45 hrs

I went back to the crèche this afternoon. Something I had glimpsed there, on my earlier visit, stuck in my mind. I spoke again to the manageress, explained that Hamid and Eugène were missing. She was very sympathetic. I asked to look at the sign-in book again. And there it was. Why had I not noticed it before? On the day they disappeared, Hamid returned to collect Eugène at 13:05, well over an hour before the normal time. Looking back through the record, there were a number of similar early pick-ups, and yet Hamid had never mentioned any of this to me, nor had they returned home early. I asked the manageress if she could confirm this. She excused herself a moment, and then returned with one of the young women who works with the children. Her name was, coincidentally, Eugenie. Yes, she said. She remembered seeing Hamid strap Eugène into the back of a silver Peugeot and drive away a little after one o’clock that day. And then she looked at me in a strange way, almost in pity. But Madame, she said. Do you not remember? I stood, nonplussed, staring at her. You were there, she said, sitting in the car. You looked at me and waved. I told the same thing to the police.

* 3 *

What It Meant To Be Alive

Clay rowed the bodies out to Flame.

The rain had stopped. One by one he lifted Grace and Joseph aboard, then carried them below and laid each on a berth. He stood in the gangway and looked at the corpses. He’d wrapped them in bedsheets and tied their ankles and around their arms and chests with rope, and now they lay, pale and still, in the rising moonlight. He looked at them for a long time – queen and prince in their floating sarcophagus, ready for their final journey into eternity.

Then he rowed back to the house. Zuz was waiting on the beach as he’d instructed, her little travel case packed and clutched to her chest. She had a mobile phone in her hand. As Clay approached she held it out for him.

‘Where did you get this?’ he asked. Grace didn’t have a mobile. The mobile system was still very new in Zanzibar, and only the most well off had their own phones.

Zuz pointed at the house.

‘One of the men?’

Zuz blanched, nodded.

Clay pocketed the phone. He rowed her out to the boat and sat her in the cockpit, where she couldn’t see the bodies of her brother and her mother. And then he went back for Dreadlock.

By the time they reached Stone Town, the sky was lightening over the Indian Ocean. Cloud billowed in the distance, dark anvils of cumulonimbus – more rain coming. Clay dropped anchor in five fathoms of water, south of the gardens and the white façade and clock tower of the House of Wonders and the old fort, away from the pier and the little notched fishing harbour. He shut down the engine, let Flame swing on the breeze.

Clay left Dreadlock in the cockpit, tied, as he’d been all night, to the starboard main cleat, and went forward to check on Zuz. He opened the forward hatch and peered down into the berth. She was still asleep, snuggled under the blankets. He closed the hatch, went below and made a pot of coffee.

‘Here’s the deal,’ Clay said, freeing Dreadlock’s good hand and passing him a mug of steaming coffee. ‘You help me find your friend, Big J, and the guy who hired you, and in return I’ll let you live.’

Dreadlock mumbled into the tape covering his mouth.

‘Just nod if you understand.’

Dreadlock nodded vigorously.

Clay took the Glock G21 from the pocket of his jacket and balanced it on his knee so the other man could see it. ‘Cross me, that arm will be the last thing you’ll be worrying about. Understand?’

More nodding, eyes wider now.

Clay yanked the tape from Dreadlock’s mouth. Dreadlock winced in pain, but managed not to spill any of the coffee. They drank.

When Dreadlock had finished his coffee, Clay pulled a sling from its package and started positioning it around the man’s broken arm. ‘Help me,’ he said, ‘and I won’t turn you in to the police. Do it well, and I’ll give you ten grand.’

Dreadlock grunted as Clay tightened the sling. ‘US dollars?’ he said, trying to keep his jaw still.

Clay pulled a wad of US one-hundred-dollar notes from his pocket and riffled the bills with his stump.

Dreadlock stared at the money a moment, mouth open, then looked up at Clay. ‘Kill him, then,’ he said, trying not to move his jaw. ‘If me help you and you no kill him, me dead.’

Clay nodded, peeled off ten notes, pushed them into the man’s good hand. Then he pulled out the mobile phone Zuz had found. ‘This yours?’

Dreadlock shook his head. ‘Big J.’

‘Can you unlock it?’

Dreadlock nodded.

‘Good. Can you find the guy who hired you – the white African?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do it. Tell him that you have my body, that you brought it over on my boat. Tell him you want to meet on the shore, over there.’ Clay raised his stump and pointed to a clutch of palms near a small beach beyond the point.

‘If he still here, Big J already tell him what de fuck happened.’ Dreadlock raised his hand to his jaw, worked the broken hinge, winced.

Clay put his British passport on the cockpit seat. ‘Tell him you found this. Read him my passport number. Tell him I brought you back to the boat, but you managed to grab my gun and shoot me. Tell him your buddy Big J ran when the fight started, that now you want the money for yourself.’

Dreadlock sat staring at the money in his hands; in this part of the world, a year’s wages – ten. ‘Him kill me,’ he said after a time. He moved his head from side to side. ‘No. Him kill me.’

Clay raised the G21, chambered a round. ‘That’s fine, then. I’ll do it myself.’ He started to depress the trigger.

‘Wait,’ said Dreadlock, sweat blooming in the big pores ranked across the bridge of his nose.

‘Decide.’

Dreadlock dropped his head. ‘Okay.’

‘Tell him one hour. On the beach.’ Clay put his passport on the cockpit seat.

Dreadlock fumbled with the phone, thumbed the keypad, raised it to his ear.

‘English,’ said Clay, pointing the gun at Dreadlock’s forehead.

Dreadlock closed his eyes, nodded.

Clay heard the phone ring, click. A conversation ensued.

Dreadlock killed the call, dialled another number. It rang, connected. A voice on the other end, a distinctive Free State accent – South African. Dreadlock nodded to Clay, spoke, stuck to the script. After a moment, he picked up Clay’s passport, opened it to the picture page, read out the passport number, listened a moment and then killed the line.

‘He come one hour,’ said Dreadlock.

Clay retied Dreadlock and went forward to check on Zuz. When he opened the hatch, she looked up at him.

‘I’m going into town for a while,’ he said. ‘I need you to stay here. Don’t leave this cabin. Do you understand?’

She nodded, blinking in the light streaming into the little cabin.

They rowed to shore, pulled the dinghy up onto the sand, walked into a palm thicket. From here they could see along the beach towards the docks and the town, but were well hidden.

Clay handed Dreadlock a 9 mm Beretta.

The look of surprise on Dreadlock’s face was almost comical.

‘There’s one round in the magazine,’ said Clay. ‘If you decide to use it, make it count.’ Clay pulled the G21 from his jacket pocket to emphasise the point.

Dreadlock took the weapon, examined it a moment, looked up at Clay. Possibilities whirled in the dark spaces behind his retinae.

‘Don’t think about it too much,’ said Clay. ‘You’ll hurt yourself. Now go and sit out there, where he can see you, and wait.’

Dreadlock hunched his shoulders, trudged out to the beach and sat on the dinghy’s gunwale.

Clay didn’t have a plan, not really. Ever since fleeing South Africa – again, for the second time in his life – he’d been operating on impulse. Part of it, by now, was simply instinct, the inbuilt impetus to survive, to kill when necessary, to adapt, to run. After losing any hope of ever being with Rania again, there had been no guiding objective, no deeper meaning. Each dawn was simply another sunrise, every gloaming just the start of another sleepless night.

Until Zuz had emerged from behind the couch, he’d been set on driving the knife into Dreadlock’s heart. Then, in the channel, still an hour out of Stone Town, he’d readied the Glock and was about to put a bullet into the bastard’s head when he’d heard Zuz calling him from the forward berth, where he’d locked her so she couldn’t get into the main cabin and see the bodies. He’d had a vague idea about making sure Grace and Joseph got a proper burial, that Zuz should be seen safely to her grandmother’s care. That, somehow, justice be done. That had been about it.

‘Shit.’ Dreadlock stood, pushed the Beretta into his waistband.

Clay looked down the beach. Two men were approaching. One was tall, fair, built like a rugby forward. The other was Red Shirt – Big J.

‘They kill me,’ whispered Dreadlock.

‘No, they won’t,’ said Clay.

‘What I do?’ Dreadlock’s voice wavered, cracked. It sounded like he was going to piss himself.

‘Just wait,’ said Clay. ‘Let them get close. Tell them you’ve got my body out on the boat. Show them my gun.’

Dreadlock shuffled his feet in the sand, raised his good arm, waved.

Clay moved deeper into the trees, crouched low, screwed a silencer onto the G21.

Big J and the white man stopped ten metres from the dinghy.

‘Where is he?’ said the white man. He had a big voice, a strong Boer accent. The bridge of his nose had been pushed sharply to one side of his face, as if the last time it had been broken he hadn’t bothered to recentre it.

Dreadlock pointed to Flame.

‘Why didn’t you bring him in?’ said Big J.

‘You run,’ said Dreadlock. ‘Leave me there.’

‘I thought you were dead,’ said Big J, glancing at the Boer. ‘I did.’

Dreadlock hunched his shoulders, pulled out the Beretta. ‘He broke my arm. But I got his gun.’

‘Well done,’ said the Boer. ‘Is that his boat?’

Dreadlock looked towards Flame, nodded. ‘My money?’

‘Our money,’ said Big J.

‘You’ll get it when I see him,’ said the Boer.