7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Claymore Straker

- Sprache: Englisch

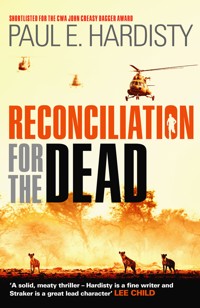

Vigilante justice-seeker Claymore Straker returns to South Africa to testify to Desmond Tutu's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, recounting the horrifying events that led to his exile, years earlier … The addictive, thought-provoking, searingly emotive next instalment in the critically acclaimed Claymore Straker series… 'A gripping, page-turning thriller that is overflowing with substance to go along with Hardisty's atmospheric prose and strong narrative style' Craig Sisterson, Mystery Magazine 'A solid, meaty thriller – Hardisty is a fine writer and Straker is a great lead character' Lee Child 'The author's deep knowledge of the settings never slows down the non-stop action, with distant echoes of a more moral-minded Jack Reacher or Jason Bourne' Maxim Jakubowski ____________________ Fresh from events in Yemen and Cyprus, vigilante justice-seeker Claymore Straker returns to South Africa, seeking absolution for the sins of his past. Over four days, he testifies to Desmond Tutu's newly established Truth and Reconciliation Commission, recounting the shattering events that led to his dishonourable discharge and exile, fifteen years earlier. It was 1980. The height of the Cold War. Clay is a young paratrooper in the South African Army, fighting in Angola against the Communist insurgency that threatens to topple the White Apartheid regime. On a patrol deep inside Angola, Clay, and his best friend, Eben Barstow, find themselves enmeshed in a tangled conspiracy that threatens everything they have been taught to believe about war, and the sacrifices that they, and their brothers in arms, are expected to make. Witness and unwitting accomplice to an act of shocking brutality, Clay changes allegiance and finds himself labelled a deserter and accused of high treason, setting him on a journey into the dark, twisted heart of institutionalised hatred, from which no one will emerge unscathed… Exploring true events from one of the most hateful chapters in South African history, Reconciliation for the Dead is a shocking, explosive and gripping thriller from one finest writers in contemporary crime fiction. ____________________ Praise for Paul E. Hardisty 'This is a remarkably well-written, sophisticated novel in which the people and places, as well as frequent scenes of violent action, all come alive on the page...' Jessica Mann, Literary Review 'A trenchant and engaging thriller that unravels this mysterious land in cool, precise sentences' Stav Sherez, Catholic Herald 'Laces the thrills and spills with enough moral indignation to give the book heft … excellent' Jake Kerridge, Telegraph 'A thriller of the highest quality, with the potential to one day stand in the company of such luminaries as Bond and Bourne' Live Many Lives 'A big, powerful, sophisticated and page-turning thriller – thought-provoking and prescient' Eve Seymour 'The writing at times is poetic, at other times filled with tension in a narrative complete with well delineated characters and several shocks. Highly Recommended' Shots Mag 'Gripping and exciting … the quality of Hardisty's writing and the underlying truth of his plots sets this above many other thrillers' West Australian 'A stormer of a thriller, vividly written, utterly tropical, totally gripping' Peter James 'Searing … at times achieves the level of genuine poetry' Publishers Weekly STARRED review 'A page-turning adventure that grabs you from the first page and won't let go' Edward Wilson

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Reconciliation for the Dead

PAUL E. HARDISTY

Contents

Glossary

B&C gear – biological and chemical protection suits.

BOSS – South African secret police, the Bureau of State Security.

Boy – South African army slang for terrorist members of SWAPO, the South West Africa People’s Organisation.

Casevac – evacuation of casualties by helicopter.

Chana – a Portuguese word for an elongated, grass-covered, natural clearing in the bush, ubiquitous throughout Southern Angola.

Doffs – Afrikaans slang: idiots.

FAPLA – Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola, military wing of the MPLA, the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Portugal), supported by the Soviet Union and its allies.

Flossie – Army slang for C-130 Hercules four-engine military transport plane.

FRELIMO – Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, the major political party in Mozambique. Formed in 1962 to fight for the liberation of Mozambique from Portugal.

Lekker – Afrikaans slang: nice, sweet.

LZ – Landing Zone.

MAG – General purpose machine gun used by South African paratroopers in the border war; fired 7.62 mm rounds from belts of two hundred.

Okes – Afrikaans slang: guy.

OP – Observation Post.

Parabat – Army slang for South African paratrooper, also vliesbom (meat bomb).

Poppie – Afrikaans slang for doll.

R4 – Standard issue 5.56 mm calibre assault rifle of South African Army; the South African-made version of the Israeli Galil rifle; semi-automatic.

Rat packs – Army slang for ration packs.

RENAMO – Resistência Nacional Moçambicana, militant organisation in Mozambique. Sponsored by the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO), founded in 1975 to counter the country’s ruling communist FRELIMO party.

Rofie – Afrikaans slang: new guy.

Rondfok – Afrikaans slang: literally ‘circle fuck’.

RV – Rendezvous point.

SAAF – South African Air Force.

SADF – South African Defence Forces.

SAMS – South African Army Medical Services.

Seun – Afrikaans: son.

Sitrep – Situation report.

SWAPO – South West African People’s Organisation, national liberation movement of Namibia.

UNITA – União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola, South Africa’s ally in the struggle against communism in Angola.

Valk – Afrikaans for hawk, the designation for a platoon of South African Army paratroopers, approximately thirty men.

Vlammies – Afrikaans, short for Vlamgat, meaning ‘flaming hole,’ slang for French-made Mirage jets used by the South African Air Force (SAAF) during the war.

Vrot – Afrikaans slang: wasted, intoxicated.

1911 – Type of handgun, originally developed in the USA as the M1911; single-action, magazine-fed weapon whose design has been adopted by numerous manufacturers worldwide.

‘The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible’

A. Einstein

‘In times of war, the law falls silent’

Marcus Tullius Cicero

For my father

Prologue

12th October 1996 Maputo, Mozambique

Claymore Straker stood in the long bar of the Polana Hotel, drained the whisky from his glass and looked out across gardens and swaying palms to the drowning mid-afternoon chop of the Indian Ocean. For the second time in his life, he’d been forced to flee the country of his birth. Two weeks ago he’d crossed the border, made his way to the ocean, and arrived here. Back again in the land of spirits, he’d determined that, this time, he would disappear forever.

And then Crowbar had showed up.

Just how his old platoon commander had managed to find him, he still had no idea. Crowbar had simply lumbered into the little café near the Parque de Continuadores and sat opposite him as if meeting for coffee in Mozambique was something they did every day.

They didn’t talk long. Ten minutes later he was gone, vanished into the braying confusion of the city.

And Crowbar had been right, of course. About the things you couldn’t change. About the apportionment of blame. About every-thing. But the relics Crowbar had left on the table that day – the canister of 35 mm film now clutched hard in Clay’s right fist, still undeveloped after all these years; the blood-stained notebook now thrust deep in his jacket pocket – had changed everything. History has a way of orbiting back at you; and promises, he now knew, while they may be broken, never die.

After he’d made the decision, it had taken the better part of a week to track her down. Time he didn’t have. In the end it had been Hamour, a one-time colleague of hers from Agence France Presse in Istanbul, who had provided the breakthrough. Although Hamour hadn’t spoken to her for more than six months, he’d heard that she’d gone to Paris. He’d given Clay the name of an associate on the foreign desk there. It was enough. Clay had been able to convince the guy that he had a story worth telling, and that only she could tell it.

He’d had her number for over twenty-four hours now, but each time he’d picked up the phone, he’d stopped mid-dial, overcome. He wasn’t sure why, exactly. Perhaps it was because of the burden he’d asked to her carry once before, the guilt he still felt. Maybe it was because of what they’d almost shared – and then lost. Memory is a strange, malleable, and, he had come to realise, wholly undependable quantity. And nothing, it seemed, was immune from time’s inexorable winnowing, that hollowing erosion that, eventually, pulled the life from everything.

‘Mais um,’ Clay said, pointing to his glass. One more.

The barman poured. Clay drank.

It hadn’t been that long ago, really. Thirteen years. He’d arrived here in late ’81, in the middle of a civil war; left in early ’83. And now he was back. The place looked different, the whole city built up now – all the new peace-time buildings. Even this hotel, the grand old lady of Maputo, had undergone a facelift. The old, caged, rosewood elevator was still here; the bar with its marble tiles and teak counters; the same palm trees outside, that much older. But so much of the past had been shaken off like dust, the dead skin of years peeled away in layers. And now that he was back in Africa, it was as if he’d never left.

A uniformed bellhop approached and glanced at Clay’s stump, the place where his left hand should be. ‘Senhor?’ That look on the guy’s face.

Clay nodded, reached under his jacket, ran the fingers of his right hand across the rough meshed surface of the pistol’s grip.

‘Your call is through, Senhor.’

Clay finished his drink and followed the bellhop to the telephone cabinets near the front desk. He scanned the lobby, closed the door behind him and picked up the phone.

‘Allo? Who is this?’ Her voice. Her, there, on the other end of the line.

He could hear her breathing, her lips so close to the mouthpiece, so far away.

‘Rania, it’s me.’

A pause, silence. And then: ‘Claymore?’

‘Yes, Ra. It’s me.’

‘Mon Dieu,’ she gasped. ‘Where are you, Claymore?’

‘Africa. I came back. Like you told me to.’

‘Claymore, I didn’t…’ She stopped, breathless.

‘I need your help, Rania.’

‘Are you alright, Claymore?’ The concern in her voice sent a bloom of warmth pulsing through his chest.

‘I’m … I’m okay, Rania.’

‘C’est bon, chéri. That is good.’ And then in a whisper. ‘I’m sorry for what happened between us, Clay.’

‘Me too.’

‘Thank you so much for the money. It has made a big difference.’

‘I’m glad.’

‘I never thanked you.’

He wasn’t going to ask her.

‘Are you going to testify, Claymore? Is that why you are there?’

‘I’ve already done it.’

‘That is good, chéri. I am proud of you. How was it?’

As he’d left the Central Methodist Mission after the first day, the spectators had lined both sides of the corridor, three and four deep. At first, they stood in shocked silence as he walked past. But soon the curses came. And then they spat on him.

Clay cradled the handpiece between his right shoulder and chin, covered his eyes with his hand a moment, drew his fingers down over the topography his face, the ridgeline of scar tissue across his right cheek, the coarse stubble of his jaw. He breathed, felt the tropical air flow into his lungs.

‘I need your help, Rania. It’s important.’

A long pause, and then: ‘What can I do?’

‘I need you to come to Maputo.’

‘Mozambique? Is that where you are?’

‘Yes.’

‘When?’

‘As soon as you can.’

Voices in the background, the screams of children, a playground. ‘Rania?’

‘Clay, cheri, please understand, it is not so easy. I have obligations.’

‘I have a story for you, Rania, one the world needs to know.’

‘Clay, I … I cannot. I am sorry. Things have changed. I am very busy.’

‘A lot of people have died for this, Rania.’

A sharp intake of breath.

‘And it’s still going on. The guy is still in his post. After all this time. It’s fucking outrageous.’

‘Slow down, Claymore.’

‘I tried to find him, Rania. They said he was in Libya, but I know he’s still here.’

‘Who, Claymore? Who are you speaking of?’

‘O Médico de Morte.’

‘Claymore, please. You are not making sense. Is that Portuguese? “The Doctor of Death”?’

‘That’s what they called him in Angola, during the war. I never told you about it. It was too … too hard.’ There were a lot of things he hadn’t told her.

‘What does this have to do with you, Claymore?’

‘I don’t have time to explain now, Rania. You have to come.’

‘Let me think about it, Claymore. I need some time, please. Can I call you back?’

‘When?’

‘At least a few days. A week.’

‘I don’t have that long, Rania. They’re after me.’

‘Mon Dieu, Claymore. What is happening?’

‘I can’t tell you over the phone, Rania.’

‘Who is after you? What is going on, Claymore?’

‘I’ll tell you when you get here.’

‘Alright, Claymore. Call me in two days. I will see what I can arrange.’

‘Thanks, Rania. Two days. This time. This number.’

Clay was about to hang up when he heard her call out.

‘Claymore.’

‘What is it Rania?’

‘Clay, I—’

‘Not now, Rania. Please, not now.’

Before she could answer, Clay killed the line. He cradled the handpiece and walked across the polished marble of the lobby to the hotel’s front entrance. A porter held the door open for him. He stood on the front steps and looked out across the Indian Ocean. The sea breeze caressed his face. He closed his eyes and felt time fold back on itself.

Part I

1

No Longer Knowing

Fifteen Years Earlier: 22nd June 1981, Latitude 16° 53’S; Longitude 18° 27’E, Southern Angola

Claymore Straker looked down the sight of his South African Armscor-made R4 assault rifle at the target and waited for the signal to open fire.

For almost a year after leaving school to enlist, the targets had been paper. The silhouette of a black man, head and torso, but lacking dimension. Or rather, as he had now started to understand, lacking many dimensions. Blood and pain – surely. Hope and fear – always. But more specifically, the 5.56 mm perforations now wept blood rather than sunlight. The hollow-point rounds flowered not into wood, but through the exquisite machinery of life, a whole universe of pain exploding inside a single body – infinity contained within something perilously finite.

Just into his twenty-first year, Claymore Straker lay prone in the short, dry grass and listened to the sound of his own heart. Just beyond the tree line, framed in the pulsing pin and wedge of his gunsight, the silhouette of a man’s head moved through the underbrush. He could see the distinctive FAPLA cap, the man’s shoulders patched with sweat, the barrel of his rifle catching the sunlight. The enemy soldier slowed, turned, stopped, sniffed the air. Opal eyes set in skin black as fresh-blasted anthracite. At a hundred metres – less – it was an easy shot.

Sweat tracked across Clay’s forehead, bit his eyes. The target blurred. He blinked away the tears and brought the man’s chest back into focus. And for those few moments they shared the world, killer and victim tethered by all that was yet to be realised, the rehearsed choreography of aim and fire, the elegant ballistics of destruction. The morning air was kinetic with the hum of a trillion insects. Airbursts of cumulus drifted over the land like a year of promised tomorrows, each instant coming hard and relentless like a heartbeat. Now. And now. And above it all, the African sky spread whole and perfect and blue, an eternal witness.

A mosquito settled on the stretched thenar of Clay’s trigger hand, that web of flesh between thumb and forefinger. The insect paused, raised its thorax, perched a moment amidst a forest of hairs. It looked so fragile, transparent there in the sun, its inner structure revealed in x-ray complexity. He watched it flex its body then raise its proboscis. For a half-stalled moment it hovered there, above the surface of his skin, and then lanced into his hand. He felt the prick, the penetration, the pulsing injection of anaesthetic and anti-coagulant, and then the simultaneous reversal of flow, the hungry sucking as the insect started to fill itself with his blood. Clay filled his sights with his target’s torso, caressed the trigger with the palp of his finger as the insect completed its violation.

Come on.

Blood pumping. Here. There.

Come on.

The mosquito, heavy with blood, thorax swollen crimson, pulled out.

What are we waiting for?

He is twenty, with a bullet. Too young to know that this might be the moment he takes his final breath. To know that today’s date might be the one they print in his one-line obituary in the local paper. To understand that the last time he had done something – walked in the mountains, kissed a girl, swam or sang or dreamed or loved – could be the last time he ever would. Unable yet to comprehend that, after he was gone, the world would go on exactly as if he had never existed.

It was a hell of a thing.

The signal. Open fire.

Clay exhaled as he’d been taught and squeezed the trigger. The detonation slamming through his body. The lurch of the rifle in his hands. The bullet hurtling to its target. Ejected brass spinning away. Bullets shredding the tree line, scything the grass. Hell unleashed. Hades, here. Right here.

The target was gone. He had no idea if he’d hit it. Shouting coming from his right, a glimpse of someone moving forwards at a crouch. His platoon commander. Muzzle flashes, off to the left. Rounds coming in. That sound of mortality shooting into the base of his skull, little mouthfuls of the sound barrier snapping shut all around him.

Clay aimed at one of the muzzle flashes, squeezed off five quick rounds, rolled left, tried to steady himself, fired again. His heart hammered in his chest, adrenaline punching through him, wild as a teenage drunk. A round whipped past his head, so close he could feel it on his cheek. A lover’s caress. Jesus in Heaven.

He looked left. A face gleaming with sweat, streaked with dirt. Blue eyes wide, staring at him; perfect white teeth, huge grin. Kruger, the new kid, two weeks in, changing mags. A little older than Clay, just twenty-one, but so inestimably younger. As if a decade had been crammed into six months. A lifetime.

‘Did you see that?’ Kruger yelled over the roar. ‘Fokken nailed the kaffir.’

Clay banged off the last three rounds of his mag, changed out. ‘Shut up and focus,’ he yelled, the new kid so like Clay had been when he’d first gone over, so eager to please, so committed to the cause they were fighting for, to everything their fathers and politicians had told them this was about. It was the difference between believing – as Kruger did now – and no longer knowing what you believed.

And now they were up and moving through the grass, forwards through the smoke: Liutenant Van Boxmeer – Crowbar as everyone called him – their platoon commander, shouting them ahead, leading as always, almost to the trees; Kruger on Clay’s left; Eben on his right, sprinting across the open ground towards the trees.

They’d been choppered into Angola early that morning; three platoons of parabats – South African paratroopers – sent to rescue a UNITA detachment that had been surrounded and was under threat of being wiped out. A call had come in from the very top, and they’d been scrambled to help. UNITA, União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola – South Africa’s ally in the struggle against communism in Southern Africa – were fighting the rival MPLA, the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, and its military wing FAPLA, Forças Armadas Populares de Libertação de Angola, for control of the country. UNITA and MPLA were once united in their struggle to liberate Angola from Portugal. But when that was achieved in 1975, they split along ideological lines: MPLA supported by the Soviet Union and its allies; UNITA by South Africa and, some said, America. That was what they had been told by the Colonel of the battalion, anyway. The Soviets were pouring weapons and equipment into FAPLA, bolstering it with tens of thousands of troops from Cuba, East Germany and the Soviet Union itself, transforming FAPLA from a lightly armed guerrilla force into a legitimate army. As a consequence, things were not going well for UNITA, and it was up to them to do everything they could to help. South Africa was in mortal danger of being overrun by the communists; their whole way of life was threatened. This was the front line; this was where they had to make their stand. Everything they held dear – their families, their womenfolk, their homes and farms – all would be taken, enslaved, destroyed if they were not successful. It was life or death.

Clay remembered the day he left for active service, waiting at the train station, his duffel bag over his shoulder, his mother in tears on the platform, his father strong, proud. That was the word he’d used. Proud. He’d taken Clay’s hand in his, looked him in the eyes, and said it: I’m proud of you, son. Do your duty. It was just like in the books he’d read about the Second World War. And he had felt proud, righteous too, excited. He couldn’t quite believe it was happening to him. That he could be so lucky. He was going to war.

That was the way he remembered it, anyway.

Clay reached the trees – scrub mopane – Kruger and Eben still right and left, on line. They stopped, dropped to one knee. It was the middle of the dry season, everything withered and brown. Crowbar was about twenty metres ahead, standing beside the body of a dead FAPLA fighter, the radio handset pushed up to his ear, Steyn, his radio operator, crouching next to him. By now the shooting had stopped.

‘What’s happening?’ said Kruger.

Eben smiled at him. ‘That, young private, is a question for which there is no answer, now or ever.’

The kid frowned.

Eben took off his bush hat, ran his hand through the straw of his hair. ‘And the reason, kid, is that no one knows. The sooner you accept that, the better it will be. For all of us. Read Descartes.’

Clay glanced over at Eben and smiled. Another dose of the clean truth from Eben Barstow, philosopher. That’s what he called it. The clean truth.

Kruger looked at Eben with eyes wide. ‘Read?’ he said.

Eben shook his head.

Crowbar was up now, facing them. He looked left and right a moment, as if connecting with each of them individually. And then quick, precise hand signals: hostiles ahead, this way, through the trees, two hundred metres. And then he was off, moving through the scrub, the radio operator scrambling to keep up.

Kruger looked like he was going to shit himself. Maybe he already had.

‘Here we go, kid,’ said Eben, pulling his hat back on. ‘Stay with us. Keep low. You’ll be fine.’

And then they were moving through the trees, everything underfoot snapping and cracking so loud as to be heard a hundred miles away, a herd of buffalo crashing towards the guns.

The first mortar round hurtled in before they’d gone fifty metres.

It landed long, the concussion wave pushing them forwards like a shove in the back. They upped the pace, crashing through the underbrush, half blind, mortar rounds falling closer behind, the wind at their backs, smoke drifting over them. Clay’s foot hit something: a log, a root. Something smashed into his stomach, doubling him over, collapsing his diaphragm. He fell crashing into a tangle of bush, rolled over, gasped for breath. And then, moments later, a flash, a kick in the side of the head, clumps of earth and bits of wood raining down on him. Muffled sounds coming to him now, dull thuds deep in his chest, felt rather than heard, and then scattered pops, like the sound of summer raindrops on a steel roof, fat and sporadic; and something else – was it voices?

He tried to breathe. Sand and dead leaves choked his mouth, covered his face. He spat, tearing the dirt from his eyes. A dull ache crept through his chest. He moved his hands over his body, checking the most important places first. But he was intact, unhurt. Jesus. He lay there a moment, a strange symphony warbling in his head. He opened his eyes. Slowly, his vision cleared. He was alone.

Smoke enveloped him, the smell of burning vegetation, cordite. He pushed himself to his knees and groped for his R4. He found it half buried, pulled it free and staggered to his feet. The sounds of gunfire came clearer now, somewhere up ahead. He checked the R4’s action, released the mag, blew the dust free, reinserted it, sighted. The foresight was covered in a tangle of roots. Shit. He flipped on the safety, inspected the muzzle. The barrel was clogged with dirt. He must have spiked the muzzle into the ground when he fell, driven the butt into his stomach. Stupid. Unacceptable.

Ahead, the grind of Valk 2’s MAG somewhere on the right, the bitter crack of AK47s. Smoke swirling around him, a flicker of orange flame. The bush was alight. He stumbled away from the flames, moved towards the sounds of battle, staggering half blind through the smoke. There was no way his R4 could be fired without disassembling and cleaning it. He felt like a rookie. Crowbar would have a fit.

By the time he reached Eben and the others, the fight was over. It hadn’t lasted long. Valk 3 had caught most of the FAPLA fighters in enfilade at the far end of the airstrip, turned their flank and rolled them up against Valk 5. It was a good kill, Crowbar said. And Valk 5 had taken no casualties. One man wounded in Valk 3, pretty seriously they said: AK round through the chest, collapsed lung. Casevac on the way. They counted sixteen enemy bodies.

Crowbar told them to dig in, prepare for a counterattack, while he went to meet up with the UNITA doffs they’d just rescued. The platoon formed a wide perimeter around the northern length of the airstrip and linked in on both flanks with Valk 3 and Valk 2. Their holes were farther apart than they would have liked, but it would have to do. After all, they were parabats – South African paratroopers – the best of the best. That’s what they’d been taught. Here, platoons were called Valk; Afrikaans for hawk. Death from above. Best body count ratio in Angola.

Once the holes were dug and the OPs set, they collected the FAPLA dead, piling the bodies in a heap at the end of the airstrip. A few of the parabats sliced off ears and fingers as trophies, took photos. Behind them, the trees blazed, grey anvils of smoke billowing skywards. Clay stood a long time and watched the forest burn.

‘Once more ejected from the breach,’ said Eben, staring out at the blaze.

Clay looked at his friend, at the streaks of dirt on his face, the sweat beading his bare chest. ‘Where’s Kruger?’

Eben glanced left and right. ‘I thought he was with you.’

‘I got knocked down before we got fifty metres. Never saw anyone till it was all over. Never fired a shot.’ He showed Eben his R4.

‘I never took you for a pacifist, bru.’ Eben jutted his chin towards the pile of corpses. ‘You must be very disappointed to have missed out.’

Clay gazed at the bodies, the way the limbs entwined, embraced, the way the mouths gaped, dark with flies. This was their work, the accounting of it. He wondered what he felt about it. ‘I better get this cleaned, or the old man will kill me,’ he said.

Eben nodded. ‘I’ll go find Kruger. No telling what trouble that kid will get himself into.’

Clay nodded and went back to his hole. All down the line, the other members of the platoon were digging in, sweating under the Ovamboland sun. He dug for a while and was fishing in his pack for his cleaning kit when Eben jogged up, out of breath.

‘Can’t find Kruger anywhere, bru. No one’s seen him.’

‘He’s got to be around somewhere. Crowbar said no casualties. Did you check the other Valk?’

‘Not yet.’

Clay shouldered his R4. ‘Let’s go find Crowbar. Maybe he’s with him.’

They found Liutenant Van Boxmeer towards the western end of the airstrip, radioman at his side. He was arguing with a black Angolan UNITA officer dressed in a green jungle-pattern uniform and a tan beret. The officer wore reflective aviator Ray-Bans and carried a pair of nickel-plated .45 calibre 1911s strapped across his chest. Beyond, a couple of dozen UNITA fighters, ragged and stunned, slouched around a complex of sandbagged bunkers. As Clay and Eben approached, the two men lowered their voices.

Clay and Eben saluted.

Crowbar looked them both square in the eyes, nodded.

‘Kruger’s missing, my Liutenant,’ said Eben in Afrikaans.

Crowbar looked up at the sky. ‘When was he seen last?’

‘Just before the advance through the trees,’ said Clay.

Crowbar’s gaze drifted to the muzzle of Clay’s R4. Clay could feel himself burn.

‘Find him,’ said Crowbar. ‘But do it fast. FAPLA pulled back, but they’re still out there. Mister Mbdele here figures we can expect a counterattack before nightfall.’

‘Colonel,’ said the UNITA officer.

‘What?’ said Crowbar.

‘I am Colonel Mbdele.’ He spoke Afrikaans with a strong Portuguese accent. His voice was stretched, shaky.

‘Your mam must be so proud,’ said Crowbar.

Eben smirked.

The Colonel whipped off his sunglasses and glared at Eben. The thyroid domes of his eyes bulged out from his face, the cornea flexing out over fully dilated pupils so that the blood-veined whites seemed to pulse with each beat of his heart. ‘Control your … your men, Liutenant,’ he shouted, reaching for the grip of one of his handguns. A huge diamond solitaire sparked in his right earlobe. His face shone with sweat. ‘We have work here. Important work.’

Crowbar glanced down at the man’s hand, shaking on the grip of his still-holstered pistol. ‘What work would that be, exactly, Colonel?’ he said, jutting his chin towards the FAPLA men lounging outside the bunker.

As the Colonel turned his head to look, Crowbar slipped his fighting knife from its point-up sheath behind his right hip.

Mbdele was facing them again, his nickel-plated handgun now halfway out of its holster, trembling in his sweat-soaked hand. The metal gleamed in the sun. Crowbar had closed the gap between them and now stood within striking distance of the UNITA officer, knife blade up against his wrist, where Mbdele couldn’t see it.

‘FAPLA will attack soon,’ shouted Mbdele, his voice cracking, his eyes pivoting in their sockets. He waved his free hand back towards the bunker. ‘This position must be defended. At all costs.’

Crowbar was poised, free hand up in front of him now, palm open, inches from Mbdele’s pistol hand, the knife at his side, still hidden. Clay held his breath.

‘And what’s so fokken important that you brought us all this way, meu amigo?’ said Crowbar in a half-whisper.

Mbdele took a step back, but Crowbar followed him like a dance partner, still just inches away.

‘I said, what’s so fokken important?’

‘Classified. Not your business,’ shouted Mbdele, spittle flying. ‘These are your orders. Your orders. Check. Call your commanders on the radio.’

Crowbar stood a moment, shaking his head and muttering something under his breath. ‘And here are your orders, Colonel,’ he said. ‘You and your men get the fok out there and cover our left flank, in case FAPLA tries to come in along the river.’

Sweat poured from the Colonel’s face, beaded on his forearms. ‘Não, Liutenant,’ he gasped as if short of breath. ‘No. We stay here. Aqui.’ He pointed towards the bunker complex. ‘My orders are to guard this. And your orders are to protect us.’

Clay glanced over at Eben. It was very unusual for a UNITA officer to question their South African allies. The Colonel was treading a dangerous path with the old man. Just as odd was UNITA clinging to a fixed position. They were a guerrilla force, fighting a much larger and more heavily armed opponent. They depended on movement and camouflage to survive.

Eben frowned, clearly thinking the same thing: whatever was in that bunker, it must be pretty important.

‘Our orders are to assist,’ said Crowbar. Clay could hear the growing impatience in his voice. ‘That means we help each other.’

The Colonel glanced back at his men. ‘I am the ranking officer here, Liutenant.’

Crowbar’s face spread in a wide grin. ‘Not in my army, you ain’t.’ Then, without taking his eyes from Mbdele, he said: ‘Straker, tell the men to get ready to move out.’

Clay snapped off a salute.

‘What are you doing?’ blurted the Colonel. ‘You … You have orders.’

‘Help us, Colonel, and we’ll help you,’ said Crowbar, calm, even. ‘We’re short-handed here. Outnumbered. Get your men out onto our flank or we ontrek. Your choice, meu amigo.’

The Colonel tightened his hand on his pistol grip. ‘This is unacceptable,’ he shouted. ‘Inaceitável.’ He rattled off a tirade in Portuguese.

Crowbar stayed as he was, feet planted, knife still concealed at his side. ‘Try me, asshole.’

The UNITA Colonel puffed out his cheeks, glaring at Crowbar, trying to stare him down.

Crowbar jerked his head towards Clay and Eben. ‘Move out in ten. Get going.’

Clay and Eben hesitated.

‘Now,’ said Crowbar.

Clay and Eben turned and started back to the lines at the double.

They’d gone about ten meters when they heard the Colonel shout: ‘Wait.’

Clay and Eben kept going.

Then Crowbar’s command. ‘Halt.’ They stopped, faced the two officers.

‘I will send half my men to the left flank,’ said the Colonel.

Crowbar muttered something under his breath. ‘Tell them to report to Liutenant DeVries.’ He pointed towards the bush beyond the bunker. ‘Over there.’

For a moment the Colonel looked as if he was going to speak, but then he swallowed it down.

It happened so fast Clay almost missed it. Mbdele was down on the ground, his gun hand in an armlock, the point of Crowbar’s knife at his throat, his 1911 in the dirt under Crowbar’s boot heel. Mbdele wailed in pain as Crowbar wrenched his arm in a direction it was not designed to go.

‘You ever think of pulling a weapon on me again, meu amigo,’ said Crowbar, loud enough so that Clay and Eben could hear, ‘and it will be the last thing that goes through that fucked-up up brain of yours.’

And then it was over and Crowbar was walking away, leaving Mbdele sitting in the dirt rubbing his arm.

‘Fokken UNITA bliksem,’ muttered Crowbar, falling in beside Clay and Eben. ‘I trust those fokkers about as much as I trust the whores in the Transkei.’

Eben grinned at Clay. ‘Quite the get-up. Those twin forty-fives.’

Crowbar glanced at Eben, but said nothing.

‘Did you see his eyes?’ said Eben. ‘He was wired up tight.’

‘Fokken vrot,’ said Crowbar, slinging his R4. ‘Fokken pack of drugged-up jackals.’

‘What’s so important about this place, my Liutenant?’ said Clay.

Crowbar stopped and squared up to Clay. ‘What’s it to you, troop?’

Clay stood to attention. ‘I just meant, those bunkers…’

‘They’re important because I say they’re important, Straker.’

‘They don’t seem like much.’

Crowbar leaned in until his mouth was only a few inches from Clay’s face. ‘The only thing you need to know is right there in your hands. Understood?’

‘Ja, my Liutenant,’ said Clay, rigid.

‘And that goes for you too, Barstow. Couple of fokken smart-arse soutpiele.’ Salt-dicks. English South Africans. ‘Now get out there and find Kruger. Take that black bastard from 32-Bat with you.’

‘Brigade,’ said Clay. ‘His name is Brigade, sir.’

‘I don’t give a kak what his name is,’ said Crowbar. ‘He’s our scout, he knows the country. Take him with you.’

Clay nodded.

‘And do it quick, Straker. Cherry like Kruger, you don’t find him by nightfall, he’s as good as dead.’

Clay and Eben started moving away.

‘And Straker,’ Crowbar called after them.

Clay turned, stood at attention.

‘I catch you again with your weapon in that state, and the commies’ll be the last thing you have to worry about. I’ll shoot you myself.’

South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Transcripts.

Central Methodist Mission, Johannesburg, 13th September 1996

Commissioner Ksole: And you are here, why, Mister Straker?

Witness: To tell the truth, sir.

Commissioner Ksole: The truth. Why now, Mister Straker? It was a long time ago.

Witness: Because, sir, it’s killing me.

Commissioner Ksole: Do you wish to apply for amnesty, Mister Straker?

Witness: If that’s possible, yes, sir. I do.

Commissioner Ksole: Can you please tell the commission, are you the same Claymore Straker who is wanted for murder and acts of terrorism in Yemen?

Witness: Those charges have been dropped, sir.

Commissioner Ksole: And, Mister Straker, in Cyprus, also?

Witness: I served time in prison in Cyprus, yes, sir.

Commissioner Ksole: And you provide this testimony of your own free will?

Witness: Yes, sir.

Commissioner Ksole: And you understand, Mister Straker, that any information provided here can, and if necessary will, be used against you in a court of law if the circumstances warrant? That this commission has the power to recommend legal action against a witness if it sees fit?

Witness’s answer is unintelligible.

Commissioner Barbour: Speak up, Mister Straker, please. Do you understand the question?

Witness: Yes sir, I do. Can and will be used against me.

Commissioner Barbour: And this incident – this series of incidents – occurred on the, ah, the border, during the war in Angola. Is that correct?

Witness: Yes, sir. While I was serving with the 1st Parachute Battalion, SADF. It was my third tour, so it would have been 1981.

Commissioner Barbour: And the UNITA Colonel, Mbdele. Did you know him by any other name?

Witness: No, sir. Not then.

Commissioner Barbour: And later?

Witness: Yes, sir. The people called him O Coletor.

Commissioner Barbour: Sorry?

Witness: It’s Portuguese, sir: ‘the Collector’.

Commissioner Barbour: Thank you. Did you ever find out what was in the, ah, the bunker?

Witness: Yes, sir, we did.

Commissioner Barbour: What did you find, son?

Witness does not answer.

Commissioner Barbour: Son?

Witness: The truth, sir. We found the truth.

Commissioner Rotzenburg: It says here, in your service records, Mister Straker, that at the time of your dishonourable discharge from the army you were suffering from mental illness, including extreme instability, episodes of random violent behaviour, complex and consistent delusions, and persistent hallucinations. Do you know what the truth is, Mister Straker?

Witness does not respond.

Commissioner Rotzenburg: Answer the question, please.

Witness. Yes.

Commissioner Rotzenburg: Yes, what?

Witness: Yes, sir.

Commissioner Barbour: That’s not what he meant, son.

Witness: Yes, I … I’ve learned to…

Commissioner Rotzenburg: Learned to what, Mister Straker?

Witness: I’ve learned to distinguish.

2

Death Rhumba Psychosis

The counterattack still hadn’t come.

They found Brigade with Valk 2. He’d just returned from patrol and was reporting his findings to Liutenant de Vries when Clay and Eben arrived with Crowbar’s orders.

‘Lost?’ said Brigade, looking up at Clay from under the peak of his bush hat. He was built like a mopane tree – hard withered core, dark sinewed limbs. He wore a jungle camo uniform and carried an AK-47. He had the darkest skin Clay had ever seen on a human being.

Clay nodded. ‘No one’s seen him since the attack.’

‘It’s my fault,’ said Eben.

‘No blame,’ Brigade said in Afrikaans. ‘Come.’

They searched through the afternoon, moving along the line, the parabats jumpy in their holes, answering in crisped tones: No, we haven’t fokken seen him.

They kept going. A while later, the sound of gunfire from down the line, back from where they’d come: R4s, AKs, sporadic, gone on the breeze a few seconds later, a rumour.

They traversed all the way to the river, found a few UNITA fighters strung out there on the left flank, loose, undisciplined. They eyed Brigade warily, like hyenas, watching him until they were out of sight.

‘What’s their problem?’ said Eben.

Brigade just shrugged.

No one had seen Kruger.

They reported back to Crowbar. He told them to widen their search radius. Find him before nightfall. And take care. The shooting they’d heard earlier was FAPLA scouts probing Valk 3’s lines. No one had been hurt. Yet.

They trudged back out through the browned grass, past the edge of the airfield, the FAPLA poes lounging around the bunkers as if on holiday, and then into the adjacent chana, weapons ready, scanning the bush. Where the hell could Kruger have gone? Had he been taken prisoner? Become separated and got lost? It was so easy to become disoriented out here, one chana so similar to the next, the sun burning in a flawless sky, the bush a brown monotony, no landmarks to guide you.

They walked on through the long dry grass, the breeze rippling the bladed sea around them, shivering through the green and yellow leaves of the mopane trees, dotted like islands. They saw no one.

A couple of hours before dusk they spotted vultures circling about a mile off. Near the edge of a small copse of mopane they found the carcass of a slaughtered elephant. Vultures scattered as they approached. There were more than twenty entry wounds in the thick grey hide. Brass scattered on the ground nearby, 7.62 mm, Russian. The tusks had been hacked off and carried away.

They moved on. A gust of wind brought a whiff of wood smoke, the lingering retch of death. They had just emerged from the copse when all three stopped and stared out across the clearing. Rotting in the sun, thick with flies, dozens of big dirt-covered bodies hulked in the grass.

‘Jesus,’ said Clay.

Eben doubled over, retched.

‘Listen,’ said Brigade.

A low moan drifted on the breeze, a whimpering that sounded almost human.

‘What the hell is that?’ Eben clutched his nose.

They picked their way through the slaughter towards the sound. Thick clouds of flies filled the air. Vultures hopped away as they approached, stood watching them, wings poised ready for take-off, their heads and necks red with blood. After they passed the birds went back to their work.

By the way the bodies of the elephants were grouped, it looked to be an entire extended family. Babies still close to their mothers, the big matriarch to the front where she’d faced up to the attackers, trying to protect her tribe. Her body was riddled with bullet holes. Her face had been cut away. A bloody chainsaw with a twisted blade lay discarded beside her.

When they found the source of the whimpering, Eben turned away and bent over, hands on his knees. It was a baby elephant. It had been trapped under its mother when she was killed, its little hind legs crushed under her enormous bulk. It looked no more than a few months old. Trapped and defenceless, the attackers had removed its tiny milk tusks while it was still alive. The baby elephant looked up at them with big dark eyes, called to them with its thin, end-of-life voice, the gaping bloody holes where the tusks had been hacked out already crawling with flies.

Clay staggered back. It was as if the creature was looking right at him, asking him to explain this abandonment, this end.

Brigade raised his AK47 and put a bullet through the little elephant’s skull.

They kept going. No one spoke. A pair of hyenas circled off in the distance, ambling towards the feast.

‘Maybe he was captured,’ said Brigade some time later, when they’d stopped to drink. They were the first words he’d spoken since they’d started out.

‘Maybe,’ said Clay, wiping his mouth. If so, God help him.

‘You are Angolan?’ said Eben. Bat-32, the Buffalo Battalion, was a special unit of the SADF, based in the Caprivi, on the border. It was comprised largely of black Angolan volunteers. The NCOs and officers were white – South African regulars, Rhodesians, a few American mercenaries.

‘My father is Angolan,’ he said. ‘I lived here as a boy. Then I moved to South Africa with my family.’

‘And now?’

‘My father is a doctor in Soshanguve Township. Near Pretoria.’

Clay nodded. The townships. You are a year out of high school – a private white high school, with uniforms and real-grass playing fields for cricket and rugby, and a swimming pool – and until a few months ago you lived with your parents in a big house with a big garden, and black garden-boys and a black cook and a black housemaid who lives out back in a little shack, and she has been with your family since you were a baby, but the rest of them came in every morning on a bus from somewhere and disappeared again in the evening back to that same place. What do you say to this wizened old man, easily thirty, maybe older, grey attacking his temples, out here with you now, a brother in arms, when he says he’s from that very township?

Brigade looked into Clay’s eyes. ‘One day, I will take you there,’ he said. ‘You can meet my family.’

Clay nodded. What could he say? Sure, broer, anytime. We’ll just waltz into the township and have Sunday dinner with your family, as if it were something that people just did. He stashed his canteen. ‘Let’s find Kruger.’

With the sun low in the sky, they looped back towards the airstrip, moved into the charred ash of the woods, the ground through which they’d advanced earlier in the day. The fire had burned itself out and smoke rose in threads from the dying embers. Ash puffed and spun from their boots and floated about them like snowflakes in the Draakensburg as they threaded their way through the skeleton latticework of blackened limbs, everything here quiet after the savagery of the morning.

When they finally found his trail the sun was half gone on the horizon, big and red so you could see the solar flares dancing on its surface, hot tongues flicking at the blushing sky.

Clay, on point, walked right past. So did Eben. It was Brigade bid them halt. He reached down and, pulling something from the ash, held it up for them to see. An old canvas bag, torn and burned. It had been ripped to shreds by the exploding ammunition it had contained. It was the remains of a Fireforce vest, just like the one Clay wore now, heavy tan canvas, six pouches across the chest for 30-round R4 magazines, the remains of the pouches for M27 fragmentation grenades along the sides. Brigade dropped it to the ground.

‘Could be anyone’s,’ said Clay.

Brigade shook his head.

It was Eben who found the R4, not far away, scorched, rendered. A bit further on, the pack, similarly charred and blistered.

He’d been hit by shrapnel, they surmised, then dragged himself some distance, trying to escape the advancing bushfire. His uniform had been completely burned away, except for one side, where he’d curled up to try to protect himself from the flames. The corpse that was Johan Kruger, 1st Parachute Battalion, SADF, lately of a small town in the Transvaal, was charred beyond recognition, like meat on a brai, the hair and skin gone, a charcoal foetus.

If the wind had been blowing in the other direction, he would have lived.

But it wasn’t and he didn’t.

They wrapped him in a poncho and carried him back to their lines, reported to Crowbar. They shook hands with Brigade, thanked him.

Under a dark continent of stars, Clay and Eben hunched in their foxholes and opened rat packs, Kruger’s corpse on the ground a few metres away. Eben fired up his primus stove and heated water for tea. The line was quiet and they didn’t have to be out in the Listening Post until 0400.

Eben handed Clay a cup of steaming tea.

‘Why do they hack the tusks out?’ Clay said, blowing steam from his dixie. ‘Why not just cut them off? That poor little bugger’s tusks couldn’t have been longer than a few centimetres.’

‘One quarter of the tusk is below the surface,’ said Eben.

They sat for a long time, silent.

After a while, Eben looked in the direction of Kruger’s body. ‘All those people back home, his family, still thinking he’s alive, going about whatever it is they’re doing as if nothing’s changed.’

Clay said nothing.

‘I should have realised he wasn’t there,’ Eben whispered. ‘Gone to find him.’

Clay sipped his tea, rubbed his aching feet. ‘It’s not your fault, Eben.’

Eben’s face was in darkness. Only the whites of his eyes shone out from beneath his bush hat. ‘I thought he was with you.’

Clay said nothing. What was there to say?

‘Poor bastard. Lying there with the fire coming towards him.’

‘Don’t, Eben,’ said Clay.

‘And there’s nothing else, Clay. Do you understand? Nothing.’

Clay reached out for his friend’s shoulder, but he pulled away.

‘This is it,’ whispered Eben. ‘Just this. Twenty-one years. All eternity before, forever after. And I told him it was going to be alright.’

‘Stop, Eben. Just stop talking.’

‘I tried to tell him. I wonder if he understood.’

‘Jesus, Eben. Put it away.’ It was the only recourse.

‘I can’t, Clay. Not anymore. There’s no more space.’

Eben had been in longer than Clay, over two years – more than double Clay’s time. He’d done a couple of semesters at university before joining up – English literature and philosophy. Unlike so many, Eben had volunteered. Told anyone who’d listen that he wanted to be a writer, sat up late at night in camp scribbling in his notebook, playing rock and roll on his tape deck. A warrior poet, he said, in the best tradition of Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves. A veteran. Old at twenty-one. They’d met the first day Clay arrived in camp. Clay had produced a cassette of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, banned in South Africa and hard to come by. They’d been friends ever since.

‘Koevoet’s been out here since seventy-six,’ Eben said, in a monotone. ‘Is it even possible? Where can he put it all?’

‘Comfortably numb, broer,’ said Clay. ‘He believes in what he’s doing.’

Eben looked up so that the starlight bathed his face. ‘Do you, Clay?’

‘Do I what?’

‘Believe.’

Clay finished his tea. ‘Get some sleep, Eben.’

Eben froze. ‘Did you hear that?’ he whispered. Eben’s hearing was legendary in the battalion. He swivelled his head, reached for his R4.

Clay’s senses buzzed. He reached for his weapon, faced their front, stared out into the darkness, strained his ears. All he could hear was the insect roar of the African night. He glanced over at Eben, his eyes wide – a question.

Eben shook his head, turned towards the airstrip. That way, he indicated with his finger. ‘There. Did you hear it?’ he said after a moment.

Clay shook his head.

‘Sounds like someone screaming,’ whispered Eben. ‘There, again.’ He pointed towards the UNITA bunker at the far side of the chana.

Clay twisted in his hole, listened. There it was, a muffled shriek, high pitched. It sounded like a wounded animal. ‘A jackal?’

‘Don’t know.’

They waited, staring into the night.

Again, moments later, the same high pitched wail, clearer now.

Eben clambered from his hole.

‘Where are you going?’

‘Check it out.’

‘Crowbar will be pissed as hell if we abandon our position.’

‘We’re supposed to be sleeping,’ whispered Eben.

‘You know what he always says, Eben. Wandering around at night. Someone could mistake you for FAPLA, shoot at you.’

There it was again, longer this time. And something else too; another sound. Shouting? It was definitely coming from across the airstrip, in the direction of the UNITA bunker complex.

‘What the hell are they doing over there?’ said Eben moving off into the darkness.

‘Shit,’ muttered Clay, scrambling out of his hole and running after his friend.

They moved quietly through the darkness. They could see lights from the bunker complex now, thin pinpoints of glowing sulphur. The UNITA fighters were sloppy. They might as well have raised a neon sign. Clay and Eben crouched about fifty metres from the bunker’s perimeter trench line. They scanned the dark ground ahead, the ridge of excavated sand. There was no movement.

And then again, the same sound, softer now, as if someone were crying, the sobs coming in a rhythm. Muffled laughter erupted from within the bunker; a group.

‘Looks like they haven’t bothered posting sentries,’ whispered Clay.

‘Surrounded by parabats, why bother?’

The crash of glass. Laughter now, clear.

‘Bastards are having a fokken party,’ said Eben. ‘After Kruger died saving their sorry carcasses.’

And before Clay could answer, Eben was up and sprinting towards the trench line. Clay scrambled to his feet and followed his friend.

‘Eben,’ he called after him, a whispered shout. ‘What are you doing? Stop, bru.’

But Eben was in full flight. Clay saw him slow, jump, and disappear into the trench. Clay sprinted after him and jumped down into the excavation. Eben was up against one side of the slumped sand wall, R4 ready. They were alone.

‘Bru.’ Clay reached for his friend’s shoulder, breathing hard. ‘Crowbar finds out about this, we catch major shit.’

Another scream, louder now, a banshee wail. Sobs. A sharp crack. The pulsing rhythm of Cuban rhumba music.

‘What the hell?’ said Clay.

Then glass breaking. Laughter, more shouting.

Eben twisted away. ‘Bastards,’ he hissed. His face was contorted, covered in sweat, his eyes wild, as if gripped by some strange psychosis. ‘They want to have a party? I’ll give them a fokken jol.’ He chambered a round and started down the trench towards the sound.

Clay started after him. ‘Eben. Leave it bru,’ he called.

But Eben was already out of sight, gone down a zag in the trench. Clay could see the glow of the lights, the noise of the party coming clear now. Then the sound of impact, thunk, a muffled grunt. Clay turned the corner.

Eben was there, a UNITA fighter crumpled at his feet. Eben looked back at Clay, eyes aflame, a lunatic grin spreading across his face. The bunker was a couple of metres away, a tarpaulin draped down over the entrance, strips of kerosene lamplight shining through the edges.

A scream pierced the night.

Eben paused, looked down at the man at his feet, up at the stars, back at Clay. For a moment, Clay thought he might turn back. But then he pivoted, whipped the tarp aside with the barrel of his weapon and disappeared into the bunker.

3

Won’t Get Out of Here Alive

Clay followed Eben in.

What he saw would stay with him until the day he died, would be among the last images shuddering through his by then tortured brain.

Blinding light, after the darkness of the African night. Eben silhouetted against burning kerosene, his shoulders broad, his R4 levelled at the hip. The overpowering smell of men – close, hot – of breath and sweat and killing having been done and more to come. The unmistakable musk of semen. The naked sweating backs of a dozen UNITA fighters, the din of raised voices, a rhumba baseline of grunted chants, and above it a single, high-pitched wail. And all along the walls of the bunker, stacks of what looked like logs, some pale, long and curved, others straighter, dark, knotted. Cases, too – wooden ammunition crates. Muslin sacks about the size of apples scattered atop a small table. Eben standing there, unmoving, the men cheering now, backs turned, still unaware of their presence.

Clay grabbed one of the sacks, stood next to Eben.

‘Let’s ontrek, bru,’ whispered Clay. ‘Before they see us.’

Eben said nothing.

Chanting now, the men roaring in a chugging rhythm, hoarse, the higher pitched accompaniment just a murmur now.

‘What the fok are they doing?’ whispered Clay.

And then the crescendo, a roar, bottles tipped to mouths, heads thrown back. The crowd swayed, parted, and the UNITA Colonel was there, facing them, still wearing his sunglasses, hiking up his trousers, his dick swinging wet and dripping in the yellow light. He stopped dead, staring at them.

Behind him, a woman. She’d been laid on her back across a table. She was naked, her legs spread wide, ankles tied to the table legs, arms stretched above her head, wrists bound. Her vulva glistened. Semen dribbled from its dilated centre. Blood oozed from her anus. Another man, trousers at his knees, stepped towards her, penis erect, teenage hard. Her chest heaved with sobs.

Clay’s stomach turned.

‘Jesus Moeder van God,’ muttered Eben.

The Colonel, recovering now, buttoned his trousers, cinched up his belt, and opened his arms wide. ‘Amigos,’ he said. ‘My South African friends. Welcome.’ He smiled, revealing two rows of strong, ivory teeth. By now all the UNITA men were facing them, big eyed, hyper alert. All except the man who’d now taken position between the woman’s legs and had begun thrusting.

The Colonel grabbed a bottle from one of his men and offered it to Clay and Eben. ‘Join us,’ he said.

Clay could see the veins in Eben’s neck filling, hardening.

The Colonel snapped his fingers, motioned to one of his men. A bare-chested soldier held out a palm of white tablets. His pectorals and abdominal muscles were like rope, coiled, defined, slick with sweat.

‘Take,’ said the Colonel. ‘Good shit.’

‘What the fok is going on here?’ said Clay.

‘The spoils of war,’ said the Colonel, smiling big. A few of his men laughed. ‘You want?’

Clay raised his rifle. ‘No I fucking do not want. Let her go, you animal, or I’ll put a bullet in your head.’

No one moved. Silence, except for the woman’s sobs, her assailant’s grunts.

One of the UNITA men reached for an AK47 leaning against the cut sand wall. Eben trained his rifle on the soldier, shook his head. The man dropped his hand to his side.

‘There is no need for this,’ soothed the Colonel. ‘We are friends here, allies.’ He thrust out the bottle again. ‘Please. Have a drink.’

‘Tell him to stop,’ said Clay. ‘Untie her.’

The Colonel stood unmoving. His men, too. Confusion in their faces. Euphoria there, too. Lust. Chances were, none of them spoke Afrikaans. The man kept fucking, oblivious.

‘You heard me’ said Clay. ‘Pare,’ he shouted in Portuguese. Stop.

The man doing the raping turned back to face them, adjusted his angle by grabbing the woman’s hips, flashed a gap-toothed grin, upped his pace.

‘Be reasonable,’ said the Colonel. ‘Two of you. Seventeen of us. Many more in the next bunker. Many.’

Clay gave him his best fuck-you smile. ‘Wrong, asshole. You’re surrounded by three platoons of parabats. Kill us, you’re dead. Every last one of you.’

‘So this is what we came here to protect?’ said Eben, clearly struggling to control the tremor in his voice. ‘What Kruger died for? A bunch of drugged-up rapists.’ He flicked his R4 to auto, steadied it on his hip.

‘Let her go and we can all walk away,’ said Clay.

The Colonel dropped the bottle to his side, looked left and right. ‘Then we have a dilemma, my friends. This woman is an MPLA traitor. A traitor. A political officer attached to the FAPLA battalion that’s out there trying to kill us. She is our prisoner.’

Eben’s R4 was up now, sighted at the Colonel’s head. The woman shrieked as her assailant pounded harder.

‘I don’t care what she is,’ shouted Eben. ‘Make him stop now, or I swear you’re dead.’

The Colonel said something over his shoulder. The man kept fucking.

Eben took a step forward. At that range the bullet would take the Colonel’s head off. But if he was scared, he didn’t show it; he just stood staring right back at Eben.

‘Stop,’ yelled Eben.

‘He will stop,’ said the Colonel.

Just then the man groaned, spasmed, stood a moment on unsteady legs, then staggered back with his trousers around his ankles.

‘Diere,’ muttered Eben. Animals.