7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

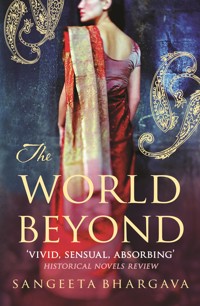

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Another sumptuous novel set in the heart and heat of colonial India, Bhargava's heroine comes to a full knowledge of herself against the backdrop of India's route to independence. 1941. Princess Malvika, or Mili, and her friend Vicky have gained entrance to one of the best schools in all of India. But the times are turbulent and the girls will not escape the changes stemming from the independence movement growing in strength around the country. But as the country finds its voice and footing as an India free from colonial rule, what place is there for Prof. Raven, the English man who comes to see Mili as more than his student?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

After the Storm

SANGEETA BHARGAVA

Contents

Title PageDedicationChapter OneChapter TwoChapter ThreeChapter FourChapter FiveChapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter NineChapter TenChapter ElevenChapter TwelveChapter ThirteenChapter FourteenChapter FifteenChapter SixteenChapter SeventeenChapter EighteenChapter NineteenChapter TwentyChapter Twenty-OneChapter Twenty-TwoChapter Twenty-ThreeChapter Twenty-FourChapter Twenty-FiveAuthor’s NoteGlossaryAcknowledgementsAbout the AuthorBy Sangeeta BhargavaCopyright

Chapter One

March. 1947. The year that would go down in history as the year India won its independence from colonial rule. But the speech Mili had just delivered had nothing to do with India’s freedom or the British.

Mili joined her hands and said, ‘Namaste,’ as the hall burst into applause. She stepped off the podium and went outside. Taking a deep breath of the pine-scented air, she tightened her shawl about her. She had forgotten how crisp and cool Kishangarh was at this time of the year. She looked at the greenery and the unspoilt beauty all around, from her vantage point at the top of the hill. The pine, deodar and chinar trees, the still waters of the lake below, the Himalayas in the distance. She watched half a dozen mountain goats bleating their way down the hill, led by a couple of Kumaoni girls with peachy skin and cheeks as red as strawberries.

A young Bhutia lad was trudging up the hill. He was bent double under the weight of the three pitaras he was carrying on his back. He reminded Mili of Badshah Dilawar Ali Khan Bahadur. She smiled. It had been a similar day in March, in the same town, when she first met him, oh so long ago. How long ago was it? Six years? Just six? It seemed more like twenty.

Mili stared at the chain of snow-covered mountains, the mighty Himalayas. They always reminded her of Ma’s string of Hyderabadi pearls – sparkling, clear and smooth. If only life was like that.

She stood upright. Who was that talking to the gatekeeper? Raven? She shielded her eyes from the glare of the sun with her hand and looked more intently. Yes, it was him. A faint smile flickered across her face. Was that a hint of a pot belly, she wondered, her smile broadening into a grin. He had put up the lapels of his jacket to keep out the cold. It added to his charm – making him look casual and yet smart.

She started running down the gravel path. But by the time she reached the gate, he was gone. She looked down the hill in dismay, then turned to the gatekeeper. ‘The English gentleman you were speaking to a moment ago?’

‘Nothing important, memsahib. He only telling me give this note to Malvika Singh …’

Mili snatched the piece of paper from him. ‘That’s me. The note’s for me.’ Clutching it in her hand, she walked over to a deodar tree near the gate. Leaning against the tree, she began to read it. It didn’t say much. Just that he was surprised to see her after all these years and would she care to join him for tea at his house that evening.

She stared at the note. A chiselled, lean face with hazel eyes stared back at her. Raven. He was laughing at her … now he was scolding her and Vicky … and now that his back was turned, Vicky was sticking out her tongue at him …

1941. Mohanagar. A lazy February afternoon. The palace slumbered while a wintry sun kept its vigil. Mili, however, was wide awake and stood looking out of her window. She watched with an amused smile as Vicky pulled herself up the low wall that surrounded the inner courtyard of the palace. Jumping to the ground with a thud, Vicky dusted her palms on her frock. Mili stood still. The sound had woken up one of the doorkeepers. She shook her head as he mumbled, ‘Oh, Vicky baba,’ and went back to sleep. Nice cushy job he had. All he had to do to earn his salary was to sleep at his post.

She turned her attention back to Vicky. She was looking around carefully. Then she scampered onto the veranda and threw a tiny pebble at Mili’s window. Mili hid behind the golden drapes and urgently held her finger to her lip as Bhoomi began to giggle. As soon as Vicky leant against the windowpane and peered in, Mili swung it open.

‘What th—’ Vicky cried as she fell into the room. Mili burst out laughing. Bhoomi stood in a corner with the edge of her sari over her mouth to suppress her giggle.

‘What the devil …’ Vicky mumbled as she came towards Mili, hands on her hips. Mili tried to back off but Vicky had grabbed her shoulders. ‘Mili,’ she shouted as she shook her.

‘Y-yes?’ replied Mili, pretending to be frightened, a frown creasing her forehead.

‘I’ve got admission in STH.’

‘I know,’ replied Mili, as Vicky loosened her grip.

‘How’d you know?’

‘Because …’ Mili’s bright eyes twinkled as she waved an envelope at her, ‘I just got my admission letter as well.’

The two friends hugged each other excitedly, like fledglings that had just discovered they could fly.

‘Such fun,’ squealed Vicky, as she pushed back her thick-rimmed glasses from the tip of her nose. ‘No more of this boring city. Where nothing ever happens …’

‘And just think,’ added Mili, fiddling with her hair that Bhoomi had plaited and tied neatly into rolls with blue ribbons, ‘no more having to take Ma’s permission for every little thing or Bauji’s ifs and buts. Oh Vicky, I’m so thrilled.’

Vicky lifted her chin and looked down her nose at Mili. ‘Princess Malvika Singh. Say thank you to Miss Victoria Nunes. If it wasn’t for my illness, you—’ She stopped speaking and gestured to Mili to look behind her. Mili turned around with a start and almost bumped into Ma.

Ma did not speak, merely nodded her head as Vicky and Bhoomi joined their hands and bowed. Mili shifted uncomfortably and began chewing her thumbnail as Ma turned to look at her. Nobody spoke. The only sound that could be heard was that of the tennis racquet hitting the ball, from the court adjoining the veranda. Must be Uday playing with that new friend of his.

‘Is it true you’ve got admission to that school in Kishangarh?’ Ma finally asked.

‘Yes, Ma,’ Mili replied, looking down.

‘I’d better go,’ muttered Vicky and started to climb out of the window.

‘We do have doors, you know,’ Ma said, a bemused look on her face. She had never been able to fathom Vicky’s ways.

Vicky scratched her head and grinned foolishly before replying, ‘Yes, of course. I forgot.’

Ma raised her hand. ‘Stay and hear us out,’ she said. She cleared her throat. ‘Mili, we know we let you apply for admission to that school on Mrs Nunes’ insistence and you have our permission to go. But your Bauji will need some convincing.’

‘Please talk to him, Ma,’ Mili said as she clutched her hand. ‘You can do it.’

‘Yes, Your Highness. He listens to you,’ added Vicky.

‘We’ll see what we can do. But it won’t be easy,’ replied Ma, thinking hard.

‘Can Mili come? With me? To see my mother?’ Vicky asked. ‘She’ll be thrilled.’

Ma looked at Vicky and then at Mili, slightly perplexed. Mili grinned. Vicky’s mind was like a racehorse, galloping from one thought to the next.

‘Please, Ma? Can we go break the news to Mrs Nunes?’ begged Mili.

‘You know we don’t like to send you to town these days because of the freedom movement. Not to mention the war …’

Mili looked at Ma with pleading, watery eyes. Ma hesitated for a moment, then shrugged her shoulders. ‘All right, then,’ she replied and turned to Bhoomi, who had been standing quietly near the door all this while.

‘Bhoomi, tell Tulsidas to take Princess Malvika and her friend to Mrs Nunes’ clinic and to bring her back in two hours.’

‘Yes, Your Highness,’ answered Bhoomi as she joined her hands, bowed and backed out of the room to look for the chauffeur.

Mili grinned at Vicky, then hugged Ma. She always smelt of sandalwood – so pious and righteous that Mili found herself examining her conscience whenever she was in her presence. ‘You’re the best mother in all the land,’ she whispered.

‘Save those words for your father,’ Ma replied as she left the room, her fragrance still lingering.

Mili walked over to her dressing table. She adjusted her blue silk dupatta and straightened the sapphire on her necklace, caressing its smooth surface as she did so.

‘Isn’t it tiresome? All this jewellery?’ Vicky asked.

‘Not at all,’ Mili replied. ‘I love it.’

Vicky stood behind her and grinned at their reflection in the gilt-edged mirror. ‘Mummum will be pleased.’

Mili looked at her and smiled. Vicky had a plain, flat face and her huge glasses gave her an unnaturally solemn look. But the moment she grinned, her entire face lit up, her eyes laughing with such merriment that one couldn’t help but smile back at her.

‘Let’s go. Ma will worry if we don’t get back before dark,’ said Mili, as she pulled Vicky towards the door.

Vicky looked at the clock that hung on the wall behind Mummum’s desk. It had taken them twenty minutes to reach her clinic from the palace. She yawned as Mummum continued to talk into the telephone. She pulled a face at Mili, who sat primly and patiently beside her. How was it possible for someone to be so well behaved all the time? she wondered. She looked around at the bare walls. Why were hospitals and clinics always so boring? Wouldn’t the patients get better faster if they had something cheerful to look at?

That’s it. She couldn’t sit still a minute longer. Her chair scraped noisily against the concrete floor as she got up. She walked over to the table that stood against the wall at the right-hand corner of the room. After scrutinising the bottles for a moment, she picked up one. Unscrewing the lid, she sniffed at it, screwed up her nose at the pungent smell and hastily slammed the lid. She opened another. ‘Yuck, this smells like phenyl,’ she muttered as she picked up a third. Umm, this didn’t smell bad at all. And the syrup looked thick, like malt. She wondered if she could taste it. She looked at Mummum. She was still on the phone but was watching her from the corner of her eye and glared at her. Vicky pulled a face again, put the bottle back on the table, pushed back her glasses and went and sat down.

‘Mummum, I’ve got admission!’ Vicky had sprung to Mummum’s side even before she had replaced the receiver on its cradle.

‘Good heavens,’ exclaimed Mummum. ‘Is it true? Is it really true?’ She hugged Vicky and kissed her hard, then embraced Mili. ‘I always knew you’d be the one to do me proud. Those sisters of yours are useless.’ She paused to look at her daughter’s face and pat her hair. ‘Mrs Gomes,’ she trumpeted to her secretary, ‘my Victoria here has secured a place at the School for Tender Hearts in Kishangarh.’

Mrs Gomes looked up from her typing and hurried over to congratulate her. She shook Mummum’s hand, then patted Vicky’s head. ‘Well done, Vicky,’ she said.

‘Victoria, Mrs Gomes, Victoria. You wouldn’t call Queen Victoria “Vicky”, now would you?’

Mrs Gomes licked her lips. Before she could reply, the other nurses and doctors had started filing into Mummum’s cabin, having heard the news.

Vicky noticed the smug look on Mummum’s plump face and smiled. Moments like this had been rare in her mother’s life. Her family had severed all ties with her when she married Papa, as he was an Englishman. Relatives are cruel. They even regarded Papa’s untimely death as divine justice and refused to accept her back into the fold. But Mummum was a proud woman. She faced life head-on. She worked hard to reach where she was now and Vicky was proud of her.

‘Thank you, thank you,’ Mummum’s loud voice boomed for everyone to hear. ‘And did you know STH Kishangarh is amongst the most acclaimed schools in this country? Until recently, ninety-five per cent of the students there were English.’

Vicky grinned as everyone exclaimed and congratulated her once again.

‘Madam, this calls for a celebration, a par—’ said Pankaj.

‘Yes, why not?’ Mummum cut in. ‘And Pankaj, don’t forget to invite Mr Chaddha. Let’s see if I can persuade him to change the second clause of the contract during the party.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’ With those words the staff dispersed and Mummum turned her attention to Mili. Taking her in her arms she exclaimed, ‘I’m so happy, my child, that you’re going to be there with my Victoria.’

Just then Tulsidas came into the room. He joined his hands and said, ‘Beg pardon, ma’am, but I fear there be rumours of trouble brewing in town. Because of the arrest of them revolutionaries.’

‘Good heavens, in that case … come on, girls,’ Mummum said impatiently, shoving the two girls towards the door. ‘You had better hurry. Oh, dear Lord, don’t let my girls come to any harm.’

Vicky walked towards the car with Mili, then went back to give Mummum another hug. She grinned as Mummum frowned at her with feigned anger, lightly smacked her on the head and said, ‘Off with you now.’

Vicky and Mili got into the Rolls-Royce. What trouble was that Tulsidas talking about? As far as Vicky could see, there was nothing unusual. It was evening. The bazaar through which they were now passing was as busy as it normally was at this time of the day. He had got Mummum all worked up for nothing.

Vicky looked out of the window. The sweet smell of jalebis wafted into the car and made her realise it was nearly time for supper. She looked longingly at the orange, syrupy sweets. The roadside vendor had piled the intricately curled jalebis one on top of the other to make a mini mountain. They beckoned to Vicky and she was tempted to ask Tulsidas to stop the car. But no, Mili was not allowed to eat anything off the streets.

‘Do you think we’ll get jalebis? In Kishangarh?’ she asked Mili, imagining herself biting into one and the orange syrup spilling over her tongue and gushing down her throat.

‘You know, I was looking at some pictures of Kishangarh. And the winding road that ran down the mountain to the valley below looked just like a jalebi.’

Vicky rolled her eyes. Mili grinned and stuck out her tongue at her.

‘Are you taking Bhoomi along? To Kishangarh?’ Vicky asked, pushing back her glasses.

‘Heavens, no. That would defeat the very purpose of my going there, wouldn’t it? I want to stay there, with you, in the boarding school. See what life is like outside the palace.’

‘But what if—’ Vicky stopped abruptly as she realised the car had slowed down considerably, owing to a large crowd that had emerged out of nowhere. There were hordes of men clad in khadi kurtas, white pyjamas and white caps. Some of them were carrying banners and shouting slogans. Others waved the Congress tricoloured flag. Every so often they would raise their hands in the air and shout, ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai. Down with imperialism. Release our comrades from prison. They’re innocent.’ There were even some women in the mob, dressed in starched cotton saris and shouting alongside the men.

‘Close window, Your Highness,’ said Tulsidas as he quickly rolled up his own.

Mili and Vicky hurriedly did the same. The car came to a halt as the crowd closed in on them. Some of them were now shouting, ‘Down with monarchy.’

Vicky looked at Mili. Her lips had gone dry and beads of perspiration were breaking out on her forehead.

‘Oh no, oh no,’ Mili exclaimed. ‘What if they break the windscreen with their sticks?’

‘Don’t worry, Your Highness. They Indians, not Angrez. They not hurt children,’ said Tulsidas as he rolled down his window a couple of inches.

‘What in Lord Kishan’s name are you doing? Getting all of us killed?’ shrieked Mili.

Tulsidas rolled down his window another inch and stuck his head out. ‘You wanting to hurt helpless schoolgirls? Indian girls? Shame on you. Back off.’ With that he hastily rolled up the window again.

A few men stepped forward and peered into the car through the windows. ‘They’re Indians. Children,’ said one, thumping the bonnet of the car. ‘Let them pass.’

The throng parted to give way and the car crawled slowly out of the bazaar.

Mili was still shaking when they reached the palace. Vicky caressed her hand comfortingly.

‘If Ma and Bauji come to know about this, they’ll never let me go to Kishangarh,’ Mili wailed.

‘Driverji,’ Vicky said to Tulsidas, ‘please don’t mention this incident to anyone. Least of all the King and Queen.’

‘Not a word, Vicky baba,’ said Tulsidas, putting a finger on his lips and shaking his head. ‘What happen today go with me to my funeral pyre.’

Bhoomi came running down the palace stairs as Tulsidas held the car door open for Mili to step out. ‘Princess, His Majesty wants to see you in his room right away,’ she said.

‘I’ll be there in a minute,’ said Mili. She looked at Vicky anxiously. ‘Do you think he knows about the mob?’ she asked.

Vicky gave her a small smile of reassurance. ‘I’m sure he doesn’t. And don’t worry, it’s over. The crowd’s gone. You’re safe.’

Mili nodded. Vicky waved out to her friend as the car pulled out of the driveway and made its way slowly to her home, just two blocks away.

The evening prayers had just been said and the smell of incense and camphor greeted Mili as she entered the palace and was ushered into Bauji’s rooms. Bauji sat regally on the armchair that stood by the window. Everything about him was big and regal and sumptuous. His bedchamber was huge, the bed king-sized. The bed linen, the cushions, the drapes – they were all heavy, shimmery, velvety. Why, even the chandelier that was tinkling at her from the ceiling was the biggest in the whole palace. He himself was a large, formidable, swarthy man and Mili was a tad afraid of him. When angry, he looked like a rakshas. But when happy, and his belly shook with laughter, he reminded her of the elephant god Ganesh, the jolly, wise god. For Bauji was an extremely wise man too. He knew a lot. He had even gone to England for higher studies.

Ma was reclining on a sofa next to Bauji’s armchair. Patting the sofa, she nodded at her. Mili sat down on the sofa tentatively. She looked at the huge rug spread before her. It was made out of the skin of twelve tigers. Or was it fifteen? Dadaji had apparently shot every one of them. She herself had been there for his last two tiger hunts, sitting behind him on the howdah, gorging on biscuits hidden under the seat for her by the servants. She had felt faint at the sight of all that blood oozing out of the tiger when Dadaji killed it. But not for a moment had she felt any fear. Well, at least not as afraid as she was of Bauji right now. Oh Lord Kishan, my Kanha, please don’t let the news of what happened in the marketplace this evening reach Bauji. Else forget Kishangarh, he wouldn’t even let her step out of the palace if he came to know about it.

Biting her thumbnail, she mumbled, ‘You wanted to see me, Bauji?’

‘We hear you want to go to a boarding school in Kishangarh?’ Bauji asked. ‘What’s wrong with your present school?’

‘Nothing, Bauji, it’s just that Vicky’s also going …’

‘Why? The schools in Mohanagar are not good enough for her?’

‘No, Bauji. She hasn’t been keeping well. The doctor feels the mountain air will do her good.’

‘Well, in that case she must go. But why do you need to tag along?’

‘Your Majesty, they’ve been together since birth. How can we separate them now?’ said Ma.

‘Sumitra, what’ll she do when she gets married?’ asked Bauji. ‘Take that girl along to her sasural as trousseau?’

Ma pushed back a lock of hair that had fallen over her forehead. ‘Let her go. It’ll be good for her. Be—’

She stopped speaking as a servant knocked and entered the room, bowed from the waist down, then placed a hookah at Bauji’s feet. He again bowed and backed out of the room. Bauji put the pipe of the hookah in his mouth and sucked. It made a gurgling sound.

‘You know we’re quite liberal,’ Bauji said after a while. ‘We’re sending her to the local school, unlike a lot of princesses who are taught at home by tutors. We don’t even observe the purdah. But boarding school?’

Mili sniffed as a sweetish smell of tobacco filled the room.

‘Times are changing, Your Majesty,’ Ma was saying. ‘The Congress is talking about democracy …’

‘That congressman – Vallabh Patel. We don’t like his views … If the English were to leave and these peasants and the low caste that Gandhi lovingly calls “Harijans” … Heaven forbid if they were to govern the nation. What would they know about how to rule a country?’

Mili looked at the rug again. Why did Ma and Bauji have to talk politics all the time? What did it have to do with her going to Kishangarh? Then she recalled the look on the faces of the men who had been shouting ‘Down with monarchy’ earlier that evening. She shuddered. They had looked menacing.

‘That’s why it’s important to send Mili out in the real world,’ Ma was saying. ‘How long are we going to shield her?’

Bauji put the hookah back in his mouth and gazed into oblivion. ‘No, Mili,’ he finally said. ‘We have given it much thought and we do not want you to go. Is that clear?’

‘Yes, Bauji,’ Mili replied in a muffled voice, as she darted from the room, blinded by tears, and flung herself across her bed.

How was she going to live without her soul sister? Bauji would never understand. Did he not wonder how two girls, so different in every way, could be such good friends? Didn’t he realise it was because they were meant to be? Like Lord Kishan and Sudama. In fact they were Kishan and Sudama, in a previous life, she was pretty sure of that. Even Nani said so. And Nani never lied.

‘Princess, dinner is served,’ said Bhoomi, coming into the room and standing beside the bed, her head bowed as always.

‘I don’t want any,’ snapped Mili, without bothering to turn around.

‘Eat a little, Princess,’ Bhoomi pleaded.

Mili swung around angrily and threw a pillow at Bhoomi. ‘Did you not hear? Go away and leave me alone,’ she snarled.

‘Yes, Princess,’ Bhoomi replied as she scuttled out of the room.

It was so unfair, Mili fumed. Why must she always listen to Bauji, even when he was being unreasonable? There had to be a way. There must be something she could do. Maybe she should run away. No one was going to keep her away from her friend. No one. Not even Bauji.

Chapter Two

Tucked away in a valley at the foothills of the Himalayas lay the town of Kishangarh. Raven could see the entire town from where he stood, atop a hill. Her beauty never ceased to mesmerise him. He watched her as she hid her face beneath a veil of mist. Closing his eyes, he breathed in her perfume – the crisp, fresh mountain air. He could hear the temple bells, which sounded like anklets on her feet. The setting sun cast a halo around her head just as the little cottages and thatched huts smiled shyly up at him. Nowhere else had he seen such untouched beauty.

Raven loved the hills, the Himalayas, the simple hill folk – the ‘sons of Himalaya’, as they liked to call themselves. But most of all, he loved Kishangarh. He was only six when Mother and he had moved here and it had been his home for the last twenty-two years; this was where he belonged. But Mother would disagree. For her, home would always be England. Raven leant against a deodar tree. He wondered what Wordsworth would have done if he had been to Kishangarh. He would have written an entire epic on its beauty, of that he was certain.

He looked over his shoulder at the sound of horses’ hooves. A couple of uniformed policemen on chestnut-brown horses rode by. He watched the horses with longing until the descending mist swallowed them and he could see no more. The doctor had confirmed that morning that he would never ride again.

Discerning some movement in the playing fields of MP College, Raven hobbled over for a closer look. Some students were playing cricket. A lanky Sikh boy with an unkempt beard and moustache and a maroon turban on his head, clad in torn khadi pyjamas and kurta, was batting on ninety-four. A peach-faced English lad began taking his run-up. Interesting. Raven went over to a bench that stood at the edge of the field, put down his crutches and sat down to watch.

The peach-faced lad threw the ball. The Sikh batsman at the crease swung his bat and hit it. The ball flew into the air and was caught by the fielder at silly mid-on. All the English fielders shouted ‘Out!’ and raised a finger.

The batsman stood his ground. ‘No, I’m not out. It was a no-ball.’

He was right. It was indeed a no-ball. The bowler strolled over to the batsman. Looking threateningly at the Sikh lad, he asked, ‘So it was a no-ball, eh?’ He tossed the ball high up in the air, then caught it himself. ‘You darkies going to teach me how to play cricket?’

The other players had now gathered around the two lads confronting each other. Sensing trouble, Raven limped towards them.

The English lad caught the Sikh batsman by his collar and punched him hard. ‘Cricket is not for uncouth boys like you. Go back to playing with your sticks and stones,’ he shouted.

The Sikh lad was about to hit his assailant with his bat when Raven barked, ‘Stop it,’ in a clipped, authoritative tone. A hush fell on the field as everyone turned to look at him.

‘Who the hell are you?’ asked the Sikh batsman. ‘Bloody gora. Hiding behind the tree and watching all the fun, were we?’

The other Indian batsman at the crease, the one clad in an ivory-coloured shirt and black trousers, touched the Sikh batsman’s shoulder lightly. ‘Let him be, Preeto,’ he said, looking pitifully at Raven’s crutches. ‘Remember, we’re not like these English. We don’t lift a finger on a cripple.’

Raven looked aghast. The Sikh smiled scornfully at him, shrugged his friend’s hand off his shoulder and spat on the ground. Then swinging his bat, he swaggered off the field, followed by the other Indian players.

Even though March heralded the arrival of spring, it was still cold in Kishangarh. Raven hobbled onto the veranda, sank into a cane chair and put the crutches on the floor. He rubbed his hands together, cupped them over his mouth, then rubbed them together again. He looked at his watch. It was almost ten o’clock. Miss Perkins should be here any minute now.

He thought of the encounter between the English and the Indian students the previous day. Scenes like that were becoming more and more common now. Earlier, the Indians would cower and hang their heads or simply walk away in such situations. But now they stood their ground, thanks to the freedom movement that was gathering momentum throughout the country, under the helm of Gandhi and Nehru. But Raven had his doubts about the tactics they were using. How was it possible to overthrow a regime without a battle? Through mere non-cooperation? It simply did not make any sense.

Not that it mattered to him whether it was the English or the Indians who ruled the country. As long as he was allowed to teach, he did not care one way or the other. Not one bit.

Through the corner of his eye, he spotted someone in white coming up the hill. He got up clumsily to greet Miss Perkins, the principal of STH, as she stepped onto the veranda. She wore an immaculate white dress, made of the softest and finest synthetic cloth. It must have been imported from Rome, he was sure of that. She was a lean woman with thick, black, bushy eyebrows, which were straight rather than arched. If he were to be honest, she looked more like a man than a woman. He smiled inwardly. It must not be difficult for her to enforce discipline in the school. Her students must surely be afraid of her.

‘You shouldn’t have got up,’ she said as she took her seat.

‘Thank you for coming to my house to see me,’ Raven said.

‘Not at all. It is I who should be thanking you for helping us out at this moment of crisis.’

Raven shrugged his shoulders. ‘It’s not a big deal. I enjoy teaching. But do you not think it is irregular for a male teacher to be the dean of the girls’ hostel?’

‘It is indeed. But we are in a bit of a fix. The current dean and English teacher decided to leave India all of a sudden, just two days back. And with school reopening next week, we are in a bit of a quandary.’

‘I see.’

‘Yes, I’m afraid we’re heavily understaffed at the moment. There is an exodus of Englishmen and women.’ Miss Perkins paused and straightened the folds of her dress. ‘India is no longer what it used to be, Mr …?’

‘Raven.’

‘Mr Raven …?’

‘I have no surname.’

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘I have no father. What need do I have of a surname?’ He watched as Miss Perkins lifted a single brow but chose not to say anything.

She cleared her throat. ‘Y-yes, as I was saying, we are short-staffed. We’ve even had to open our doors to Indian and Anglo-Indian students. The only other option was to shut the school.’

‘I will, however, be teaching at MP College as well. I’ve made a commitment to the college authorities.’

‘I’m surprised. As one of the youngest professors in this country, I’d have thought you’d have no dearth of jobs. Then why choose a college for Indians?’

‘Students are students. I was offered the job and I accepted.’

‘It’ll not be too much for you?’

‘No. It’s just one lecture a day. And as the school and college are next to each other …’ Raven shrugged his shoulders. ‘I’m sure I can manage that.’ He looked up as Mother walked onto the veranda.

‘You have met my mother?’ he asked Miss Perkins by way of introduction.

‘Yes, I think we have met once before at the school fair,’ replied Miss Perkins, extending her hand to Mother.

After exchanging niceties, Mother turned her attention to Raven. ‘Oh dear, you’re sitting in a draught. It’s so cold. Come inside.’

‘I’m fine, Mother. Stop fussing.’ He turned to Miss Perkins. ‘Mother has become extra protective since my accident.’

He stopped speaking and listened, as the faint sound of slogans – ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai. British leave India. Down with imperialism’ – reached him. He could see a peaceful procession of khadi-clad revolutionaries marching down the dirt track below.

‘When I see all this,’ Miss Perkins was saying, ‘I feel happy and secure for my girls that we’ve got a male staff member amidst us now.’

‘Well, we, the English, thought we were building a haven here in Kishangarh – a home away from home,’ Mother was saying. ‘Alas, what we had run away from in the plains has followed us here as well.’

But Raven was not listening to either of the two. As he watched the revolutionaries and heard them shout, different images and sounds began filling his head. Voices from the past; an order given – ‘Fire!’; the sound of bullets being fired; agonised shrieks of pain. And then a stunned silence. Followed by an occasional crackling of flames and the smell of burning flesh.

Chapter Three

It was on a mild morning in March 1941, the year Mili turned seventeen and Vicky sixteen, that Mili found herself in Mohanagar railway station. She looked at Vicky, who was pushing her way through the throng with ease. She scurried to keep up with her friend, her two thick plaits, tied up around her ears like sausages, swinging to and fro. She was glad she was wearing her soft-soled dainty velvet shoes which did not make a sound as she walked. Like the padded soles of a tiger on the prowl. Unlike Vicky’s ankle boots which were tric-trocking noisily on the platform and drawing everyone’s attention. If Mili’s shoes made that racket, she would have died of embarrassment. But not Vicky. She simply grinned and strutted even more.

They had come early, the two of them, along with Uday and five servants. Reason – they were too excited. Ma could not take it any more and shooed them out of the palace.

‘Princess, the train come in half an hour,’ said Bhoomi as she dusted a bench. ‘We wait here.’

Nodding, Mili sat down on the bench. She loved coming to the station. It had the feel of a funfair that never ended. The pheriwala selling colourful wooden toys, the thelewala selling an assortment of sweetmeats which drew more flies than customers, the chai waala selling cups of hot and sweetened tea. Mili had had a sip of that tea once. It was disgusting and smelt of kerosene oil.

‘What now?’ she mumbled as she saw a group of khadi-clad lads making their way down the station. ‘These revolutionaries are everywhere. Such a nuisance.’ But unlike the crowd that had surrounded their car last month, this mob was smaller and without any sticks, flags and banners. One of them was carrying a big wooden box with a slit down the middle of the lid.

Mili smiled nervously as Vicky looked at her. Vicky pressed her hand reassuringly. ‘Relax. They’re just asking for donations. They’re not going to cause any trouble.’

Shouts of ‘Vande Mataram, Bharat Mata ki Jai’ now rent the air. The man carrying the donation box was giving an emotional recount of Bhagat Singh’s martyrdom. ‘Bhagat Singh,’ he was saying to the crowd that had gathered around him, ‘suffered untold torture, fasted for days and finally gave up his life. He was only twenty-three when he died. Only twenty-three. If a mere lad could do so much for his motherland, what I’m asking from you is very small.’ He pointed to the wooden box. ‘We are in dire need of funds to carry on our struggle against the British Raj. Please donate generously to help remove the shackles of slavery from our Hindustan. Jai Hind.’

‘Jai Hind. Bharat Mata ki Jai,’ the mob shouted in response. People started pouring money into the donation box. Mili grimaced as some women got emotional and began tearing off their jewellery and putting it in the box as well. As the revolutionaries came nearer, she hastily pulled her yellow dupatta over her head, hiding her gold earrings studded with rubies and diamonds as well as the matching necklace. She was not going to let anyone make her part with her precious jewellery.

Uday gave her a nudge. ‘Boo-hoo, Bauji won’t let me go to Kishangarh,’ he mimicked. ‘I thought you didn’t get permission? Where you off to then?’ he said, tweaking her plait.

‘Stop teasing,’ Mili pouted. ‘He did refuse.’

She remembered how that had upset her. She hadn’t eaten at all that day. In the evening she had been summoned to the garden by Bauji. He was having his afternoon tea with Mother. Mili went and stood beside the table, her hands behind her back, her chin tilted defiantly.

Bauji took a sip of his tea. Then he put down the cup on the table. He was taking his time. Mili looked around. The lawns were neatly trimmed, the rows of flowers straight. That’s how Bauji liked his gardens – not a single blade of grass out of place. And that’s how he wanted his daughter’s life to be, Mili suspected. Regimented and orderly. That’s how princesses were supposed to live.

‘Sumitra tells me you haven’t had your breakfast or lunch today,’ Bauji said.

‘What do you care? If you really cared, you’d understand how much it means to me to be with my friend,’ Mili retorted.

‘Now now, Mili, that’s no way to speak to your father,’ said Ma.

‘I’m sorry,’ Mili muttered. This was the first time she had dared speak to Bauji in that manner.

‘So is this fasting to do with the fact that we did not give you permission to go gallivanting to the mountains?’

‘She wants to go there to study, Your Majesty,’ chided Ma.

Mili looked thankfully at Ma. She often thought it strange that she should address Bauji as “Your Majesty”.

Ma spoke again. ‘Why are you torturing the poor child? They have been friends ever since she was a baby, even before Vicky was born …’

‘We were only thinking about her well-being, Sumitra. She is used to the comforts and luxuries of the palace. How will she manage on her own?’ said Bauji.

‘She’ll learn,’ replied Ma. ‘Tomorrow, both the girls will get married. Proposals have already started coming for Mili. Then they will have to go their separate ways. But at least until then, let them be together.’

Bauji sighed and took another sip of his tea. ‘All right, then, she can go,’ he finally conceded.

‘Oh thank you, Bauji,’ said Mili, clapping her hands together. She looked at Ma gleefully.

Ma was smiling softly. She looked so petite whenever she was beside Bauji. He often teased her about her height. Mili had heard that when she was pregnant with Uday, Bauji would sigh and exclaim, ‘What if all our children take after you and are stunted? That’ll be the death of our dynasty.’ But although Ma was small, she carried herself with such grace and quiet authority that she commanded the respect of everyone, including Bauji. Yes, even Bauji. For all his temper and arrogance, he was putty in Ma’s hands. As she had just witnessed …

‘I’m happy for you,’ Uday was saying. Mili stared at him, then looked around the platform. The revolutionaries were leaving the station. She had been reminiscing and not heard a single word of what he had been saying. He was now raising his arm and exclaiming theatrically, ‘Step out of the four walls of the palace, sister, and explore the world.’

‘I think your palace has more than four walls,’ Vicky said with a grin, pushing back her glasses.

Uday looked at Vicky. ‘These glasses are good,’ he said. ‘You can see now.’

Vicky stuck out her tongue at him.

‘But Uday, you have to admit – you’re going to miss us,’ Mili said. ‘Who will cover up for me when I’m in trouble?’

‘Yes, I suppose,’ replied Uday. ‘The palace will be quiet without your silly pranks and giggles.’

‘If Bauji—’ Mili stopped speaking as she noticed a lot of hustle and bustle on the platform. A minute later the train thundered into the station. She looked around at their luggage. Thank goodness they didn’t have a mountain of it like they did whenever Ma was travelling with them. ‘Ma, it’ll be easier to put wheels under our palace than to get that lot into the train,’ Uday used to joke.

She watched as the servants carried all the bags and suitcases into the train before getting into it herself, followed by Vicky. Calling out to Bhoomi, she asked her to open the window. Then peered out. A sudden hush seemed to have fallen. The crowd on the platform was parting and now stood on either side of the main entrance with heads bowed and hands joined respectfully. That could only mean one thing – Ma and Bauji had reached the station.

‘Don’t forget to write to us if you need anything,’ said Ma as she patted her frail hand through the bars of the window. ‘Bhoomi, did you remember to put the stationery in her trunk?’

‘Yes, Your Highness,’ Bhoomi replied.

‘And the bottles of pickle are in the basket. Make sure they don’t fall over,’ Ma continued to fuss.

‘Yes, Ma. Now stop worrying. Vicky will be there to take care of me.’

Ma looked at Vicky and smiled. ‘We’d never send you off on your own. Imagine my little Mili going out into the big bad world all by herself. And did you pack your coat? Remember, it’ll be cold up there.’

‘Ma …’ Mili began to protest.

Bauji had finished giving instructions to the servants and turned his attention to Mili. ‘My child, take care of your health. Don’t study too hard. See how it goes for three months. If you don’t like the school, come back.’

‘Yes, don’t stay up too late and get dark circles. Then nobody will want to marry you,’ added Ma.

‘Ma …’ Mili protested yet again, just as the whistle began to blow.

Bauji and Ma stepped back from the train and waved to her. Mili frowned as a woman bulldozed her way through the crowd. She was panting.

‘Mummum,’ exclaimed Vicky, ‘I thought you’d never make it.’

‘What a to-do, Victoria. I got caught in this meeting and then these people were taking out a procession on the road …’

Vicky put a loving hand on her mother’s, through the bars of the window. ‘I understand, Mummum. Don’t explain. Just take care of yourself. And don’t worry about me. I’ll be fine.’

‘I know, sweetheart. My brave poppet,’ said Mrs Nunes.

Mili watched Mrs Nunes as she wiped her face with her handkerchief. Perspiration had made her make-up runny and her kohl smudged. She was now looking around, then joined her hands and said ‘Namastey, Your Highness,’ to her parents. Now she had turned back to Vicky and was asking, ‘Where are your sisters?’

‘Claudia was getting late for her rehearsal. And Michelle had an important class she couldn’t miss,’ said Vicky.

‘Brats … all right, poppet, take care of yourself and Malvika,’ said Mrs Nunes as the guard blew the whistle. She waved and blew a kiss to Vicky as the train began to chug slowly.

Mili and Vicky chatted late into the night. It was difficult to recall when exactly they had drifted off to sleep, but it was morning when they awoke and the train was pulling in at Shaampur station. If only Mili had known then that they would never take this train together again, she might have stayed up all night.

Mili straightened her crushed dupatta before alighting onto the platform. Vicky’s Uncle George had sent his chauffeur to drive them up to Kishangarh. Mili nodded as the driver gave the two girls a friendly grin. He stepped aside to let them pass through the station gate and asked Bhoomi and the rest of the servants to follow him with the cases. Then it was time for goodbyes.

‘The moment you need me, Princess, you tell, I come,’ said Bhoomi.

‘Yes, Bhoomi, I definitely will,’ replied Mili holding her hands lightly. Then she smiled and waved to all the servants and got into the jeep. Once Mili and Vicky had been bundled inside, the vehicle made its way up the spindly road.

For miles around, Mili could see a chain of hills and mountains, covered with coniferous trees. They had been driving at a snail’s pace for the last three hours. Sometimes the road slithered along like a long grey snake stretching right across the hills. At other times, it spun around a hill like a top, right up to the summit. And there were so many sharp turns and corners that Mili was left clutching her stomach and feeling very, very sick. Hey Lord Kishan, was this journey ever going to end?

Just then the road opened up to reveal a valley below. They were now in Kishangarh. As they reached the top of a hill, the jeep swerved around a bend and a mansion came into view. Engraved on the gatepost were the words ‘School for Tender Hearts’.

‘STH,’ Vicky cheered loudly, as the driver hopped down to open the gate. Then he changed gear and took the jeep up the muddy track, right up to the main school building.