7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

1855, Lucknow. As tensions simmer in the heat of colonial India, a prince of Avadh and an English woman defy their societies' prejudices to fall in love. But in a world where private happiness is at the mercy of wider events, even as Salim and Rachael are drawn closer together, their privileged lives are about to be torn apart. Trouble begins when the British annex Avadh and banish the king. Determined to recover what is rightfully his, Salim seizes the chance to fight back when a small mutiny flares into bloody rebellion against British rule. As unrest spreads across the subcontinent, the ancient city of Lucknow proves one of the most dangerous places to be. Torn between their loyalties to each other, their families and the opposing sides that threaten to raze the city to the ground, can Salim and Rachael's love prove strong enough to rise above the devastation surrounding them, and survive together to a world beyond?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

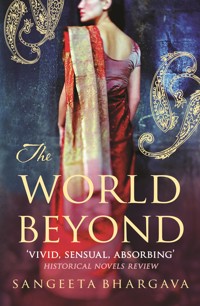

The World Beyond

SANGEETA BHARGAVA

For my father without whom this book

Contents

Title PageDedicationCHARACTER LISTChapter OneChapter TwoChapter ThreeChapter FourChapter FiveChapter SixChapter SevenChapter EightChapter NineChapter TenChapter ElevenChapter TwelveChapter ThirteenChapter FourteenChapter FifteenChapter SixteenChapter SeventeenChapter EighteenChapter NineteenChapter TwentyChapter Twenty-OneChapter Twenty-TwoChapter Twenty-ThreeChapter Twenty-FourChapter Twenty-FiveChapter Twenty-SixChapter Twenty-SevenChapter Twenty-EightChapter Twenty-NineChapter ThirtyChapter Thirty-OneChapter Thirty-TwoChapter Thirty-ThreeChapter Thirty-FourAuthor’s NoteGLOSSARYAcknowledgementsAbout the AuthorCopyright

CHARACTER LIST

NAWAB WAJID ALI SHAH/ABBA HUZOOR/ABBU – the last king of Avadh

BEGUM HAZRAT MAHAL/AMMI – one of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s wives

SALIM/CHOTE NAWAB – Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s adopted son

AHMED – Salim’s cousin

DAIMA – Salim’s wet nurse

NAYANSUKH – Daima’s son

CHUTKI – Daima’s daughter

RACHAEL BRISTOW – an English girl

COLONEL FELIX BRISTOW – Rachael’s father

MRS MARGARET BRISTOW – Rachael’s mother

PARVATI/AYAH – maidservant

RAM SINGH – Parvati’s husband

SUDHA – Rachael’s companion and maid

CHRISTOPHER WILSON – Rachael’s childhood friend

Chapter One

SALIM

It was 1855. The month of Ramzan, the holy month. Prince Salim and Ahmed pushed their way through the bustling narrow by-lanes of Chowk. Chowk – the grand old bazaar of Lucknow, the haunt of the famous courtesans, the hub of the city. There was not a single article in all of Hindustan that could not be found in Chowk. You needed the keen eye of a huntsman, that’s all.

A light breeze brought with it the aroma of khus – the cool refreshing smell of summer. Salim paused to look at the rows of decanters in the perfume shop. Ruh gulab ittar – made by distilling the heart of rose petals; musk ittar – procured from the scent that is found in the gland of the male musk deer; jasmine, tuberose, sandalwood …

‘Which ittar is an aphrodisiac, Salim mia? Musk or rose?’ Ahmed asked.

Shrugging his shoulders, Salim moved on. He didn’t know, neither did he care to know. If love meant having a dozen wives in your harem like Abba Huzoor, he didn’t care. He would sooner man an army than settle squabbles between numerous wives. Just then his ears pricked up, like a deer’s at the sound of a tiger’s footfall. He could hear the sound of ghungroos and the fall of feet in time with the tabla. A husky voice was reciting the dadra – ‘dhaa dhin naa dhaa tin naa’. Looking up at the apartment above the shop, Salim found a eunuch standing in the doorway dressed in a woman’s attire.

She winked at him. ‘Come upstairs, sweetheart. I’ll get you whatever your heart desires.’ She bit her lower lip coquettishly and played with her long plait, as she measured him from the top of his nukkedar cap to his short-toed velvet shoes.

Averting his gaze, Salim looked at Ahmed. He was grinning at the eunuch and trying to look past her into the house, hoping to catch a glimpse of the prostitutes who resided there. Shaking his head at his cousin, Salim pulled him roughly as he hurried along. Nay, Ahmed was not just his cousin. He was more than that. He was his brother, his best friend, the keeper of all his secrets.

‘Why did you choose today of all days to come here, Salim mia?’ Ahmed shouted above the din.

‘No, thank you, I don’t want any,’ Salim said brusquely as he pushed aside the garlands of jasmine a vendor had shoved right in front of his face.

‘D’you know what Ahmed-flavoured keema tastes like?’ Ahmed asked as he wiped the beads of perspiration from his forehead.

Salim’s brows knitted together. ‘What?’

‘Well, you’ll come to know today. Because if this crowd doesn’t make mincemeat of me, Daima surely will.’

Without bothering to answer, Salim hastened his pace. Daima mustn’t come to know he’d been to Chowk. As they passed Talib’s Kebabs, Ahmed dawdled and sniffed appreciatively. Salim had to admit – he sure did make the best kebabs in town, the type that melt in your mouth. The pungent smell of fried onions, garlic and grilled meat tickled his taste buds.

‘Thank goodness it’s the last day of Ramzan,’ Ahmed muttered, as he eyed the kebabs one last time.

Salim walked purposefully towards a little shop at the end of the road. It was almost hidden from view by the bangle man’s stall.

‘Show me those green bangles, bhai jaan,’ said one of the women gathered around the stall.

‘Bhai jaan, do you have those red ones one size smaller?’ said another.

‘Bangle man, can you give me two of each colour?’ clamoured a third.

Throwing a cursory glance at the women, Salim strode into the music shop. There before him was the choicest collection of musical instruments that had ever been seen in Hindustan. Bade Miyan smiled at him, bowed slightly and pointed to a sarod. Salim’s eyes lit up as they rested on the instrument.

As he bent down to pick it up, a slender white hand reached out for it as well. Their hands touched. Salim looked up and found himself gazing into a pair of eyes as blue as the Gomti at the deep end. He could see no more. The woman was clad in a burqa. He looked at her hands again. They were as soft and white as a rabbit. On her little finger she wore a delicate gold ring with a single diamond.

Salim hastily withdrew his hand and with a slight bow said, ‘It’s all yours, ma’am.’

The woman nodded slightly and their eyes met again. Just then he felt a sharp kick and almost yowled in pain as Ahmed’s foot hit the corn on his big toe. But the lady in the burqa was still looking at him, so he suppressed his scream and the urge to slam his fist into Ahmed’s face and grinned instead – a broader grin than he had intended. Then, lowering his gaze, he left the shop.

‘What if her father was just behind us, Salim mia?’ asked Ahmed. ‘He’d have surely beaten us up if he had seen you gaping at his daughter like that.’

‘Whether her father would’ve beaten us up or not, you’re getting bashed for sure,’ Salim said, waving his fist at him. Ahmed ran off laughing with Salim hobbling after him.

Sitting down on the takhat, Salim took off his khurd nau with a curse. He gingerly rubbed the corn on his big toe and cursed Ahmed yet again.

‘So finally you’re here, Chote Nawab?’

It was Daima. Salim smiled affectionately at her as she gestured to the eunuch Chilmann to bring in the basin. Chilmann, who wore the clothes of a man but swayed like a girl. The butt of all the jokes in the palace.

Salim washed his hands and face.

‘Where did you rush off to this morning?’ Daima asked, as she stopped pouring water and handed him a towel.

‘Bade Miyan wanted me to see the new sarod that was delivered yesterday,’ he replied carefully as he wiped his hands. He had never been able to lie to Daima. He looked at her now, noticing for the first time that her hair had begun to match the white of her sari. He waited for the lecture to come – a prince has no business nosing through dilapidated bazaars like a common man.

‘Where is it?’ she asked.

‘Where’s what?’

‘The sarod …’

‘Oh. Actually there was a young maiden in the shop …’

‘So of course, our Chote Nawab let her have it …’ Daima clicked her tongue. ‘This chivalry of yours is going to destroy us one day.’

Salim hugged her from behind. ‘There’s no need to be so dramatic, Daima. It was just a sarod after all.’ Then turning to Chilmann he said, ‘Tell Rehman to have Afreen and Toofan saddled by four.’

‘You’re going out again?’ asked Daima.

‘I won’t be late. And no, I haven’t forgotten that it’s Chand Raat.’

‘Yes, finally, the last day of Ramzan … just look at the way all this fasting has made your bones stick out.’

Laughing, Salim took off his cap absent-mindedly and placed it on the stool. Yes, thank goodness the fasting period was almost over. He was missing his hookah.

‘And mind you, don’t be late for namaz tomorrow … you know how it upsets your father.’

‘Ya Ali, dare I displease Abba Huzoor on Eid? How is it, Daima? He never misses a namaz, not a single one!’

‘Chote Nawab, the day you remember to say all the five namaz, Allah mia will be so pleased, he will personally come down from Heaven to bless you.’

Salim grinned. He ran his fingers through his hair as he watched Daima’s receding form. She had nursed him as a baby and was the closest he had known of a mother’s love, his own mother having died during childbirth. She fawned on him and made sure everyone called him Chote Nawab and paid him the utmost respect, even though he was not the heir apparent. Just an adopted son of the ruler, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah.

He chuckled as he heard Daima chiding someone in the adjoining room. ‘Hey you, move those limbs a bit faster … otherwise we’ll have to serve the feast next Eid.’

Even though she was a devout Hindu, she had comfortably fitted into his Muslim family and commanded as much respect in the palace as any of the begums.

Taking off his angarkha and silk pyjamas, he threw them on the takhat. Chilmann picked them up, folded them carefully and put them away. Salim slipped on a loose cotton kurta and pyjamas. Walking over to his bed, he propped himself on the oblong pillow as two attendants hastened to fan him. He spread his hands over the crisp white sheets. They felt cool and refreshing under his warm moist palms. It was the middle of June and the heat showed no signs of relenting for at least another month. He lay back on the pillow and thought about the girl in the burqa. Her hands were so dainty – just like paneer – soft white cottage cheese. Ya Ali, was he hungry!

It was that time of the year when even the evenings were warm, but twilight sometimes ushered in a cool breeze from the River Gomti. The city of Lucknow yawned and stretched after its afternoon nap and slowly began to deck itself for a night of festivities, on this night of the moon or Chand Raat.

There would be considerable excitement that night, especially among the children, as they competed with one another to be the first to spot the moon. Shops would be open all night to enable people to get on with their last-minute shopping. The women would get busy applying henna to their hands.

As Salim and Ahmed neared the Gomti, they saw some mahouts lead their elephants to bathe in the river. Salim patted Afreen and she trotted to a halt. He watched as the mahouts gave the elephants a thorough wash. They were being primped for the procession to the Jama Masjid tomorrow. Soon oil would be rubbed into their skins. Once that was done, their foreheads, tusks, ears, trunks and feet would be painted with a rainbow of lines and colours and adorned with ornaments. A couple of brass rings would be slipped onto the tusks. Finally their backs would be covered with brightly coloured, embroidered, velvet cloths. On top of that would be placed the gold or silver howdahs.

‘Ahmed, isn’t that Nayansukh?’ Salim asked, distracted by a figure in red approaching them.

‘Nayan who?’ said Ahmed.

‘Daima’s son.’

‘Ah, so it is!’ replied Ahmed as he trotted up to him. ‘Why in Allah’s name are you undressing in the middle of the road?’ he asked with amusement as he watched Nayansukh tug impatiently at the gold buttons on his coat.

‘These angrez are crazy! Make us parade in the heat in bloody coats! I can’t even breathe. It’s so bloody tight under my arms,’ Nayansukh replied, as he finally managed to wriggle out of the coat. He walked over to Salim. ‘Salaam, Salim bhai. We ought to wear just vests and lungi in this bloody heat, you know.’

Laughing aloud Salim replied, ‘Soldiers marching in just a loincloth! Ya Ali, there’s an image!’

Nayansukh slapped Afreen’s back and said wistfully, ‘Seriously, bhai, I wish I hadn’t enlisted in the Company’s army.’

‘But it was Daima’s dream,’ Salim said. ‘She always wanted to see you as a soldier …’

‘Aren’t you happy?’ Ahmed asked.

Nayansukh stroked Afreen’s mane and, looking down, replied, ‘The salary’s fine, but they’ve taken away our land.’

‘No,’ Salim said in a lowered voice.

‘Yes. Can you imagine Salim bhai? Those bloody firangis took away my ancestral land and I could only stare after them. They took my property from under my nose and all I could do was twiddle my thumb.’ He angrily smacked Afreen’s rump. Afreen snorted in protest. ‘And all thanks to that firangi – what’s his name? Dalhousie.’ Nayansukh turned his face away and spat on the side of the road. His voice was choked when he spoke again. ‘Now where will I find the money for Chutki’s marriage?’

Chutki. Daima’s little girl, with her small glistening eyes and sharp nose. Who never forgot to tie a rakhi on his arm or put tika on his forehead on bhai dooj. Sometimes Salim felt she was fonder of him than her own brother, Nayansukh.

Touching Nayansukh’s shoulder lightly, he said in a quiet voice, ‘Don’t worry about Chutki. She’s my sister too. I’ll make sure she has one of the grandest weddings in Lucknow.’

‘It’s not just me, Salim bhai,’ Nayansukh continued. ‘Most of the Indian soldiers are unhappy.’

Afreen snorted and swished her tail to drive away the flies that were trying to settle down on her back.

‘And know what? Senior Indian sepoys are the most frustrated. They’ve been in the army for as long as I remember. But they can’t get promoted over the most junior English sepoy.’ Nayansukh paused and twirled his moustache angrily. ‘I swear on Lord Ram, the young dandies are so rude. Makes my blood boil. And if we protest, we are given our marching orders.’

Salim looked at Nayansukh as he continued to twirl his moustache. He knew promotion wasn’t the only reason why the Indian soldiers were dissatisfied. There were other issues. Several of them.

Nayansukh broke into his thoughts. ‘Where are you two off to?’ he asked.

‘Going back to the palace to break our fast,’ Ahmed replied. His stomach growled as though on cue.

Chuckling, Salim said, ‘Ahmed, you’d better not overeat tomorrow. You don’t want to spend the next ten days dashing to the hakim like last year.’

‘The last day of the fasting period is the most difficult, Salim mia. Ammi has already started cooking for the feast and all those smells coming from the kitchen …’

Salim shook his head. Poor Ahmed. He fell silent as they rode towards Kaiserbagh. He thought about Nayansukh and what he had said about Dalhousie’s reforms. He smiled scornfully. East India Company. A mere bunch of traders from England. And now, the lord and master of practically all of Hindustan.

He wiped the perspiration from his forehead. How he hated that Dalhousie. It wasn’t just because he was a firangi. It was his attitude towards the Indians, his arrogance, his high-handedness that got to him. If only he would leave Hindustan and go back to where he belonged. And take all his whimsical policies with him. He looked at Ahmed. He had grown quiet as well, but his silence had more to do with an empty stomach, Salim suspected. They rode in silence for another five minutes, then Salim abruptly brought Afreen to a halt. He patted her apologetically. She was foaming at the mouth.

‘Now what?’ Ahmed asked.

Salim didn’t answer. His eyes and ears were transfixed to the open window of the bungalow in front of them. An English girl sat at the piano. Salim stood still. He had never heard such feisty music before. He could not see the face of the pianist clearly. But her hands – they were the same slender white hands he had seen that morning – the same ring, the same diamond, glinting in the setting sun. Her fingers were running confidently from one end of the keyboard to the other, dancing merrily as to a lively jig.

‘Ya Ali,’ he exclaimed incredulously, ‘it’s the same girl we saw in Chowk this morning!’

Chapter Two

RACHAEL

Everybody clapped as Rachael finished the piece with a flourish. She curtsied slightly and thanked them. Anna took her place on the stool and started playing a ballad.

‘That was beautiful, Rachael. Was that Mozart?’ asked Mrs Wilson.

‘No, Haydn,’ Rachael replied as she carelessly flicked a golden lock of hair away from her forehead

‘I wish I could practise like you, my love. But I can never find the time. What with the washerwoman always misplacing Christopher’s shirts and Kallu forgetting to put up the mosquito nets …’ Mrs Wilson stopped mid sentence to accept a glass of wine from the waiter. As she thanked him, Rachael excused herself and went outside.

She was relieved to be away from the stultifying heat and the even more stifling conversations within. She did not care how many days the washerwoman took to do the ironing or how slow Kallu was in laying the table. She watched two horsemen disappear into oblivion, whipping up a cloud of dust behind them. What would she not do to saddle up and ride alongside them? She grinned devilishly as she imagined the look of horror on the faces of all the guests at home.

Rachael loved looking at the skyline at this hour. The white palaces and mosques, bedecked with golden minarets, domes and cupolas, looked flushed and pink as the sun set slowly behind them. Like a virgin bride blushing in all her bridal finery. As the incantation of Allah-o-Akbar rose from the mosques, a dozen sparrows flew into the air.

She took a deep breath. The air was laden with the scent of roses and jasmine. She stooped to pick up a rose that had fallen on the lawn and started plucking its petals one by one. ‘Yes,’ she sighed contentedly. Lucknow certainly was more beautiful than Paris or Constantinople. She wondered what those palaces and mosques looked like from the inside. Did the women wear burqas inside the palace as well? She had heard Nabob Wajid Ali Shah had many begums. She wondered how they lived together. Did they live in harmony like sisters or were they always quarrelling? If only she could spend some time with them. And Urdu – the language they spoke – it sounded so poetic, so rich, so polite. And the way it was written from right to left – it was intriguing. One day, Rachael decided, she would learn to read and write in that language.

Mother, of course, would not approve. She had no interest in India or its people. ‘The less I know about these heathens and their ways, the better,’ she would say. Rachael pitied her. She had no idea what a treasure trove of excitement she was missing. How narrow and shuttered her life had become.

Rachael propped her elbows on the little wicker gate that led into the garden. The gate creaked in protest against the unaccustomed weight. She thought of the young man she had met in Chowk that morning. He had looked her straight in the eye – unlike the other natives, who never looked a woman in the eye unless she was his mother, wife, sister or a nautch girl. He was no ordinary native – he walked like one who owned the land. Who was he? A prince? But no, he did not wear any jewellery like all the nabobs and princes she had seen. So who was he, then? She blushed slightly as she caressed her right hand and remembered how his firm brown hand had touched it.

The following morning, Rachael thought about the previous night’s party as Sudha brushed her hair. She would run away from home if Mother made her attend one more party that week. And what made all these social gatherings even more unbearable was whether it was a party or a ball or the theatre, they invariably met the same insipid crowd. Added to that was the matchmaking all the mothers were now indulging in since the day she had turned eighteen.

‘Captain O’Reilly has just arrived in Lucknow and he’s single. You must invite him next time, dear,’ crooned Mrs Palmer.

Another one whispered conspiratorially into Mother’s ear, ‘Stella’s youngest son – what’s his name – ah, Thomas – that freckled Rebecca has given him the mitten. He’s a free man now.’

For the love of God! Had she told them to look for a suitable boy for her? Did she look desperate? Then why were they so anxious to get her betrothed? Had they nothing better to do? It seemed the only purpose in a woman’s life was to go to the altar. And how that thought vexed her.

Sudha stepped aside as she threw back her stool and turned away from the dressing table. She had had enough of this matchmaking. Next time someone said a word about marriage she would scream. Even if it meant being banned from English society for ever.

She went into the dining room and looked around. Breakfast was going to be late. The servants were still busy clearing the mess from yesterday’s party. The room smelt of stale food and liquor.

‘Oh my God, memsahib, something wrong with puppy,’ Ram Singh suddenly exclaimed.

Turning around sharply, she rushed to where Ram Singh was bending over something. Sure enough Brutus was acting in the strangest manner. He was spinning his head rapidly. Then he put his head down on the floor and rubbed it up and down against the carpet. Ayah looked at him and screamed, ‘Oh no, he possessed by evil spirit! Someone call the tantric!’ She scurried out of the room to call Mother.

Rachael bent down over the puppy. ‘What’s the matter, baby?’ she cooed. She patted his soft black back and tried to scoop him in her arms. But he simply yelped and leapt out. He continued shaking his head, as though trying to rid himself of something.

‘What’s the matter? What’s all this hullabaloo?’ said a startled voice from behind. It was Mother – her eyes puffed and still sleepy, hair tousled.

If there was one person who had strongly opposed keeping Brutus in the house, it was Mother. But Brutus had soon won her over. He followed Mother everywhere. He wagged his tail briskly and yelped in delight whenever she got back home. He looked at her with such sorrowful eyes whenever she scolded him that she began to soften. So much so, that now, if there was one person in the entire household who stirred any emotion in Mother, it was Brutus.

If Rachael did not eat her meal, it often went unnoticed. But if Brutus did not eat, one servant was sent right away to summon the vet, another to the market to get some fresh meat and a third was ordered to roll out rotis just as Brutus liked them – thick and soft. And until Mother finally managed to coax Brutus to eat, she would sit with him on her lap, stroking his coat and whispering sweet nothings into his ear.

Smiling sadly, Rachael wondered when was the last time mother had hugged her. It was so long ago it did not matter anymore. Mother’s lack of warmth and affection had hurt a lot when she was little. She would break Mother’s favourite china or throw tantrums to evoke a reaction from her. But nothing ever worked. Finally she had convinced herself that Mother was her stepmother. Just like Cinderella’s.

‘What’s happened to my Brutus?’ There was an edge of panic in Mother’s voice now, as she helplessly watched Brutus running around.

As Rachael moved aside to enable Sudha to lay the table, she spotted something on the floor and picked it up. It looked as if it had been chewed and then spat out. ‘Nothing to worry about, Mother,’ she announced. Grinning, she held up something green for all to see. ‘Brutus has just had his first taste of green chillies.’

Her declaration was greeted with oohs and aahs and mirth. Ayah went to fetch Brutus a bowl of water while Sudha scraped some leftover pudding from the dish for him.

Once Brutus had been fed and watered and lay contentedly on his rug, Mother commenced her tour of the house. ‘Sudha, why have these dead flowers not been replaced?’ she said, as she lifted the bunch of flowers from the vase in the living room and handed them to her.

‘Sorry, memsahib, I do it right away. You see, they alive yesterday.’

‘And Ram Singh, I want you to remove all the cobwebs behind the khus mats at once. I felt mortified last night when Mrs Wilson noticed them.’

‘Very well, memsahib,’ replied Ram Singh.

As Mother lifted a khus mat to point out the cobwebs to Ram Singh, a lizard fell on her. She screamed and shook her garments vigorously to get rid of the hideous creature.

‘Mother, pray sit down and have your breakfast. You can instruct them after you’ve eaten,’ said Rachael.

Mother sighed and sat down at the table. ‘Oh, these dim-witted natives. They have again put the wrong cutlery.’

‘Pray do not vex yourself, mother. They’ll learn eventually. Your breakfast is getting cold.’

But Mother was already marching towards the kitchen. She yanked open the cutlery drawer and, lifting out a spoon, waved it at Ayah. ‘This is the spoon—’ She could not finish as a cockroach darted out of the drawer. ‘What the—?’ she gasped, horrified.

Poor Mother. ‘You don’t like this country much, do you, Mother?’ Rachael had asked her once.

‘I hate it,’ she had barked in reply.

Yes, Mother hated India. She hated the uncouth natives; the heat and the dust; the hot curries and the leathery Indian bread; the smell of perspiration, strong spices and cow dung. Above all she hated the country for swallowing her only son.

Rachael squinted as the glaring sun beat down on her as soon as she stepped out of the house later that day.

‘Good afternoon, missy baba,’ Ram Singh greeted her.

She smiled and crinkled up her nose. ‘Afternoon, Ram Singh.’

She had known Ram Singh since she had learnt to walk. When she was two, Mother had often asked him to keep an eye on her. She would throw her toys out of the window, then clap her hands with glee as he ran outside for the umpteenth time to pick them up.

When she was older, he and his wife Parvati often told her tales from the Ramayana and Mahabharata.They would tell her about the cousins, the Pandavas and the Kauravas, and how they waged an eighteen-day war against each other. Or how Lord Ram was the only mortal who could lift the celestial bow to win Sita’s hand in marriage. She would listen in awe as the monkey god Hanuman set fire to Lanka with his tail, or Lord Krishna lifted an entire mountain on his little finger to save his fellow villagers from a thunderstorm.

The couple would often quarrel over details. Angrily, Ayah would pull the edge of her sari over her eyes so she could not see her ignoramus husband’s face anymore, and stomp off. Ram Singh would shake his head at her receding form, and then continue the tale.

Today, as Rachael passed the servants’ quarters, she halted. ‘What’s that lovely aroma coming from your house, Ram Singh?’

‘Missy baba, my son ask wife to make kheer. You like taste some?’ he added hesitantly.

‘Yes, why not?’

She followed Ram Singh but hesitated at the doorstep. In all the years that she had known him, she’d never been inside his house. Even as a child she had understood it was not the done thing. Sahibs and memsahibs did not mix with the natives. But then Ram Singh and Ayah weren’t just any natives. They were almost like family. Rachael lifted her right foot determinedly and entered the house. The door was small and she had to bend down to enter. A peculiar smell greeted her – a mixture of sweat, food, incense and camphor.

‘Oh, missy baba, I no knew you come. Welcome, welcome. You sit, baba, over here. No, here,’ Ayah chattered, wringing her hands as she spoke.

‘You sure, missy baba, you like to eat in our house?’ Ram Singh asked her for the third time.

She now suspected he had invited her out of politeness, but had not expected her to accept the invitation. But she couldn’t possibly refuse now. She sat down quietly on the chair that he had dusted and put out for her. He then excused himself and followed his wife to the kitchen.

‘Parvati, hurry up and serve food. If barre memsahib and sahib come and find missy baba here, they skin me alive,’ Rachael heard him say, and she felt guilty for putting him to such trouble.

She looked around. The room was too small for even one person to live in. The roof was low and there was just one small square window in the entire house. Rachael wondered how Ram Singh and his wife survived in this heat. The only furniture in the room was a charpoy, a wooden table, a chair and a cupboard.

‘No, no, no, I’m happy eating on the floor,’ Rachael insisted when she saw Ram Singh clearing the clutter from the table. And before he could protest, she had settled down on the threadbare rug on the floor. The floor felt hard, but she said nothing. She did not wish to add more to the couple’s discomfiture.

Ayah placed a plate of food before her and started fanning her with a punkah.

‘I’m not eating alone. Where’s your plate?’ Rachael asked.

‘Oh no, baba, how can I eat before husband?’ Ayah answered shyly as she continued to fan her.

‘Ram Singh, come and join me,’ Rachael called out to Ram Singh, who had stationed himself at the door and looked out nervously every two minutes.

‘No baba, you eat. I eat later.’

‘Look, I’m not going to eat alone. Either you or Ayah eats with me or I’m going.’ Rachael started to get up.

‘Oh no, missy baba, you know not how bad it is for a guest to leave table without eating,’ said Ram Singh. Reluctantly he sat down on a small chatai and gestured to Ayah to bring his food.

Rachael licked her lips. She had never eaten without any cutlery before. She was relieved when Ayah handed her a small teaspoon she had managed to dig out. She spluttered as she took the first mouthful of the vegetable pulao. It was spicy and hot, but oh so delicious. ‘Where’s Kalyaan?’ she asked as she took another mouthful. What was that special aroma – was it the bay leaves, the green cardamoms or the black ones? How come English food always smelt healthy but never exotic like this?

‘He eaten and gone to tend the horses,’ said Ayah.

Rachael smiled as she thought of Kalyaan. Many an afternoon she had spent with him as a child; until the fateful day when she had that fall. That was the last time she played with him. For thereafter, much to her consternation, she was whisked off every afternoon to Granny Ruth’s – that’s what everyone called her.

Mother took a siesta every afternoon with clockwork regularity. She locked her bedroom door and nobody, not even Papa, was allowed to disturb her then. And certainly not her. But Rachael could never bring herself to sleep during the day. The world outside beckoned her. She’d creep out of the house and join Ram Singh’s son in his games. He’d defeat her at a game of marbles or teach her how to climb a tree. That afternoon, as she was climbing the guava tree, the branch snapped and she had a nasty fall. Mother had to be woken up and, of course, she was not pleased. She was scandalised to learn her daughter had been climbing trees. Rachael had to endure an hour-long lecture on the impropriety of playing with the natives while the nurse tended to her wounds.

Granny Ruth was a frail old woman with a high-pitched nasal accent. At first Rachael abhorred her, until she introduced her to the enchanting world of music. From then on, Rachael began leading a secret life every afternoon, when only she and her piano existed. Her notes would rise to the skies and inhabit a world full of laughter and ecstasy. By the time the afternoon ended, her face would be flushed, fingers aching and eyes starry.

‘You not liking food, baba?’ Parvati asked.

Looking down at her food, Rachael realised she had been daydreaming. ‘Umm … What’s this?’ she asked, pointing to the bowl Ayah had just placed before her.

‘Kheer … sweet?’

Rachael took a spoonful. A kind of dessert. Tasted a little like rice pudding. Just then she heard the creak of a rusted gate being opened and the sound of horses trotting to a halt and neighing.

‘Oh my God, sahib here. I going to be skinned alive,’ Ram Singh groaned.

‘Shh, listen to me, Ram Singh. Tell me when they are inside the house and I will sneak into my room through the window.’

Stepping out of Ram Singh’s house gingerly, Rachael looked around. No one was about except for the gatekeeper who sat yawning at the post. She glanced across the garden. Everything was still, as though drugged on opium. She lifted her skirts and scurried to the back of the house where her window was, as a hot gust of wind hit her.

Suddenly she heard someone coming. She held her breath and closed her eyes. Then she heard a small bark. She opened her eyes slowly and found Brutus wagging his tail, his tongue hanging out and his little head cocked to one side as he looked at her.

‘Oh Brutus, it’s you,’ she exclaimed as she slowly let out a sigh of relief. Her heart was still thumping rapidly as she reached for the window latch.

‘Rachael?’

She froze. It was Papa.

Chapter Three

SALIM

Salim had just returned to his rooms after offering the Eid prayers. He was relieved Daima wasn’t around. Despite her warning yesterday, he had managed to oversleep and reach the Jama Masjid late. Although he had slipped into the prayer hall quietly after washing his hands and feet, he had espied Abba Huzoor noticing him from the corner of his eye.

He walked over to the latticed window and looked out into the courtyard below, while the barber prepared his shaving foam. There was a hum of activity – servants ran helter-skelter, completing last-minute preparations for the Eid celebrations. New expensive carpets from Persia were being rolled out in the hall. As usual, food was being prepared in all the six royal kitchens.

Salim sat down on the takhat and the barber began to apply shaving foam to his cheeks. He thought of the girl in the burqa whom he had met the previous day. She had the most beautiful pair of eyes he had ever seen – cool, calm and as blue as the sky at midday. It irked him, however, that the girl for whom he had felt a tug for the first time in his life was not Muslim. She was English. Damn, but she played the piano so well!

Just then Ahmed entered the room. ‘Eid Mubarak, Salim mia,’ he said.

The barber stepped aside as Salim got up to embrace his friend. ‘Eid Mubarak, my friend. Eid Mubarak.’

Salim sat down on the takhat again and the barber recommenced his shaving.

Ahmed walked over to the painting of a European lady in her boudoir that hung on the wall. He ran his finger alongside the frame, then turned to face Salim. ‘Can I ask you something, Salim mia?’

‘What is it, Ahmed?’

Clearing his throat, Ahmed looked around. ‘Salim mia, the girl we saw yesterday. You sure it was the same girl? An English mem in a burqa?’ He put a paan in his mouth. ‘I think you’ve lost it, Salim mia. You’ve started hallucinating. Better start visiting the tawaifs.’

‘I’m absolutely sure,’ Salim replied, an edge of irritation in his voice.

‘But if she was Eng—’

‘Look, I don’t wish to have anything to do with an Englishwoman. So can we please drop the subject?’

Ahmed’s smile vanished. ‘Oh well, I must get going. Ammi is waiting for me. I’d just come to wish you “Eid Mubarak”,’ he mumbled and left the room before Salim could stop him.

The barber wiped Salim’s face with a towel, packed his shaving kit, bowed and backed out of the room. Salim looked out of the window. He sighed as he watched Ahmed dodging the servants at work in the courtyard. He shouldn’t have spoken to him in that tone. He could still remember the first time he had met him. It was Eid on that day as well. He was about five years old then. Upset the wind had torn his new kite, he had stomped into the palace.

‘The biggest kite in the whole of Avadh,’ the shopkeeper had assured him. ‘The king of the skies,’ he had added with a wink as Salim reluctantly handed him all his eidi.

Some king, Salim thought ruefully. Well, the king was in shreds now. He was about to throw a tantrum for Daima’s benefit when he saw him – a boy with a round face and a cheery dimpled smile. His maternal uncle’s son, he was told.

‘Eid Mubarak,’ the boy said.

‘Eid Mubarak,’ Salim replied. ‘How old are you?’

‘Four.’

‘What?’ How could it be? He was plumper and taller than him.

‘Here, you can have mine,’ the boy said, as he handed a surprised Salim his kite.

Since that day in 1838, the two of them had stuck together like the two drums of the tabla. Each incomplete without the other.

They had got into many scrapes together. They had fallen from the guava tree, been chased by a mad bull, been punished by the moulvi at school. They had tried to learn to whistle through the gap between the teeth when they lost their first baby tooth; they had kept their first fast during Ramzan together; they had even visited Lol Bibi’s kotha together at the age of twelve, only to be chased by the gatekeeper. They had been together when Salim had almost killed the woodcutter. Yes, killed him, almost.

An involuntary shiver ran down Salim’s back. Even after six long years … he pursed his lips, shook his head and tried to think of something else.

Somehow news of their antics had always reached Daima. And always, much of her scolding was directed at Ahmed. She never was fond of him. She felt relatives like him were parasites, a drain on the royal treasury. If only she knew who the real scroungers of the treasury were. Moreover, she firmly believed Chote Nawab could do no wrong.

Ahmed soon got used to her tongue-lashings. The good-natured soul that he was, he would cheerfully listen to her. Like the time when she scolded them for playing in the rain and her vitriolic tongue got the better of her.

‘Nothing will happen to you, you son of a rhino,’ she scolded, waving her arms accusingly at him. ‘But our Chote Nawab here, he’s of blue blood. He’ll be struck down with pneumonia.’

Ahmed had simply strolled over to the basket of fruit and dug into the juiciest apple. Daima stared at him while he busied himself crunching and slurping the apple and licking the juice that ran down his fingers.

Yes, that was Ahmed. He never answered back, which strangely fuelled Daima’s anger even more. For him, there was a simple solution to every problem – food.

Little wonder Eid had always been his favourite festival. As boys, the two of them had loved waiting at night on the terrace to catch sight of the moon; the new clothes, the lip-smacking food. Above all, they had loved hoarding all the money they received as eidi, to buy kites.

They had always been welcome in the kitchen, especially the day before Eid, when the chef could not taste the food because of his fast. In Salim and Ahmed he found willing guinea pigs.

‘What else would Chote Nawab like to have?’ the chef would ask.

‘Anardana pulao,’ he would answer, dipping his paratha in the thick sweet and sour mango murabba and licking his fingers. He loved anardana pulao more for its appearance than the taste. Half of each grain of rice was fiery red and the other half white, thus giving them the appearance of pomegranate seeds.

But what Ahmed enjoyed eating most of all as a child was siwaiyaan – vermicelli cooked with milk, sugar and lots of dry fruits and topped with balai, or clotted cream.

Salim ran his finger over the rim of the cut-glass lamp that stood on the stool, then looked out of the outer window facing the palace gates. Ahmed was crawling towards the gates, his shoulders slouched. Salim pursed his lips. He had better make it up to him tomorrow.

Salim took his seat at the dastarkhwan and hastily glanced around. The floor of the banquet hall had been covered with Persian carpets, over which starched white sheets had been spread. Abba Huzoor had taken his seat of honour, flanked by his mother Begum Janab-e-Alia and his wife Begum Khas Mahal. It was difficult to imagine such a big man with so much grace, and yet he was one of the most graceful and dignified men Salim had ever met.

He was, however, glad to be seated far from him. Who’d want to be admonished for being late for prayers on Eid? He stifled a smile as he saw Choti Begum, who sat next to him, looking at Begum Khas Mahal’s new gharara with envy. She saw him watching her and showed him the henna on her hands.

‘It’s beautiful,’ he said politely.

‘Thank you, Chote Nawab,’ she replied, blushing, and looked away. She was not much older than him.

He wrinkled up his nose. He would never let his wife apply henna. It smelt of rotting mint leaves.

The servants started bringing in the trays of food. One of them almost tripped over the edge of the sheet spread out over the carpets.

There were hundreds of delicacies. Several varieties of pulao – anardana pulao, moti pulao where the grains of rice were made to look like pearls; several types of bread: chapattis, parathas, and sheermal – unleavened bread made with milk and butter with saffron on top. There was quarma and zarda and a variety of kebabs; biryani, lentils and fried brinjal. Then there were the murabbas, pickles and chutneys – accompaniments to the main meal. For dessert there was rice pudding, sohan halwa, jalebi, imarti and other sweets. And of course, siwaiyaan, without which Eid would be incomplete. There were pieces of meat carved in the shape of birds and placed on platefuls of pulao – it seemed they were pecking at the grains of rice.

Stealing another glance at Abba Huzoor, Salim was filled with a mixture of awe and pity. He was wearing a new brocade angharka, a heavy gold necklace, a pearl necklace and earrings. Salim could never bring himself to wear jewellery. Too much of a bother. Abba Huzoor, however, always made the most of such occasions. Perhaps it was to convince himself more than anybody else that he was the ruler of Avadh and not a mere puppet in the hands of the Company.

Salim turned his attention to his little brothers, who were making big plans about their eidi.

‘I’m going to buy a hundred marbles,’ boasted little Jamaal.

‘I’m going to spend all my eidi on jalebi,’ Birjis Qadir announced as he stuffed his mouth with gulab jamun.

‘That’s my marble,’ little Salman wailed.

‘I was just looking at it,’ Jamaal retorted.

Birjis Qadir clapped his hands loudly. A hush fell in the hall and all eyes turned to the little prince, including Abba Huzoor’s.

‘Jamaal, we order you to give back the marble to Salman,’ said Birjis Qadir, looking sternly at his cousin.

Jamaal scowled as Salman yanked the marble out of his hand.

Salim smiled. He patted Birjis Qadir’s head lovingly as he helped himself to another shami kebab. ‘I think you’re fit to be a king,’ he said to the little boy. Little did he know his prophesy would soon be fulfilled.

Birjis grinned. He was eleven, the son of Begum Hazrat Mahal, Salim’s stepmother and a woman he openly admired.

Salim turned towards the entrance as he heard everyone clapping and cheering. It was the head chef. He entered the hall with a flourish. He held a silver tray with the biggest pie Salim had ever seen. As soon as the pie was cut open, a host of little birds were revealed. There was a sudden cacophony of sounds in the hall – the astonished excited chatter of the children, the amused prattle of the grown-ups and the twitter and flutter of feathers, as the birds tried to fly away.

Looking at all the happy faces, at the sumptuous banquet spread out before him, Salim sighed. Why did lavish preparations like this make him feel as though he was living on borrowed time?

Salim slouched over Afreen as he and Ahmed trotted along. It was the morning after Eid. The festivities were over and had left him feeling bloated and lethargic. Even the air was still and languid. He looked up at the cloudless sky and groaned inwardly. It was going to be even warmer than yesterday. He felt sorry for the servants who were following them on foot.

As they neared the parade ground, Salim looked askance at the marching soldiers. Although they looked smart in the Company’s scarlet coats and black trousers, they were sweating copiously. The commanding officer bellowed attention and the sepoys halted in neat rows before the dais, with a click of their heels.

Salim grinned and shook his head as he watched Nayansukh, who stood right in front of the platoon. He was twitching his nose at the Sikh sepoy who stood right next to him. Must be the smell of the curd they used for their long hair.

The commanding officer now ordered his men to stand at ease. He then shouted, ‘First company, first platoon, step forward and pick up your rifles and cart—’ He was distracted by a figure approaching him from the west. It was an elderly soldier who was jogging towards the podium, panting.

Salim sat upright and cupped his right hand over his eyes to get a better view. Why, it was Ramu kaka, Nayansukh’s uncle. Salim tugged Afreen’s rein and brought her to a halt.

While the rest of the soldiers stood still, Ramu kaka walked up to the dais, his hands joined in supplication.

‘You’re late,’ barked the commanding officer who now stood over him.

‘It not my fault—’ Ramu kaka muttered.

THWACK!

The officer had slapped Ramu kaka right across his cheek. Salim was aghast and looked at Ahmed in disbelief. Ahmed was equally bewildered. With an exclamation of ‘Ya Ali’, Salim pulled Afreen’s rein. He was about to charge into the parade ground when Ahmed put a restraining hand on his arm.

‘Don’t lose your cool, Salim mia,’ he said quietly. ‘Remember, this is the Company’s army, not your Abba Huzoor’s.’

‘But how can that firangi slap a man double his age?’ Salim asked. ‘Does he have no respect?’

The commanding officer raised his hand again. Ramu kaka cowered. Just then another hand stopped the officer’s hand in mid flight. It was Nayansukh’s.

‘This man is old enough to be your father,’ Nayansukh hissed slowly through clenched teeth. ‘I will break your hand if it goes anywhere near Ramu kaka again.’

The commanding officer turned on Nayansukh. ‘How dare you, you uncouth barbari—’