Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hesperus Press Ltd.

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Alexander is a stunning work of historical reimagining from a troubled and unjestly neglected writer. Written in 1929 by the son of Thomas Mann, Alexander shows why Klaus Mann is regarded in Germany as one of the foremost writers of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 347

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Alexander

A Novel of Utopia

Klaus Mann

Translated by David Carter

Contents

Foreword

It is difficult to be something and to have the air of being something. I have always feared the beautiful which had the air of being beautiful, the noble which had the air of nobility, the grand which had the air of being grand, and so on. As with physical elegance, moral elegance consists in a way in making itself invisible. It may be imagined with what fear I approached an Alexander… an Alexander the Great. It is fair to say that this Alexander made a brave appearance; in our era of short books it was a large volume. Furthermore it came to me from Klaus Mann, a young man who is closely accompanied by charm, intelligence and the most moving kind of fame, that of Thomas Mann, his father, who knows that greatness does not always dwell in great things. A little boy swinging on a little gate can move us more than the procession in Parsifal.

This family and familiar greatness of Thomas Mann illuminates a very gentle halo around Klaus Mann (a luminous child’s hoop, if you will) and saves him from the pitfalls of malice.

Alexander! In secondary school he was a model in the drawing class, a profile in plaster, an eye in plaster, curls in plaster, and that nostril, that lip, cold enigmas in which the schoolboy quickly discovers a rearing horse. This profile had been brought alive for me, had been given a three-quarter turn, thanks to what was imagined to be the manual by Princess Bibesco: The Asian Alexander. It seems to be a manual at least, to judge by the format of the book, its cover of supple leather, its ribbon page-marker and the name of the Larousse company. This oriental Alexander disorientated me, but orientated the legend for me like a pearl, and orientated my mind towards a more human superhuman being.

I become bored as soon as I cannot sense the presence of that truth which derives from neither justice nor a code, but from a secret system of weights and measures. With Princess Bibesco the large, vague form became clearer to the extent of becoming a small, precise and disturbing thing, not with the precision of a medal but with that of a flower: an upright hero, with curly hair like a hyacinth, and spreading around him a strong perfume.

The Alexander of plaster is replaced by this figure of hideous beauty, a veritable rebus of the same quality as the masterpieces of the modern style, the ectoplasm of which seems to be flowing from the mouth of a sleeping woman.

This time, by the intervention of a young poet, nourished, I repeat, by lines, figures and reliefs and not by that monumental fog of German legends, there is the profile of the whole face. Drawing the model full-face is the draughtsman’s way of being frank.

Well, this is how Klaus Mann shifts the shadows of the myth, brings it closer to us and embodies it: Alexander has two student friends. There is one friend who watches him and whom he dominates; and another whom he watches and who dominates him.

Certain poets preserve their childhood; others find it again. They all remain serious, hard, hidden and frightening, as childhood is. I pity the people who despise this school fairy world, those battles in which a snowball can leave its mark on us forever and can forever dry up the springs of the heart.

Briefly, Alexander wants to surprise this friend whom nothing amazes, to put to sleep a little those too-open eyes which observe him; and that will be the true motive for his exhausting march towards conquest, towards that victory which forces the conqueror further into loneliness, a loneliness which the smallest amount of progress will encumber with tourists and strew with greasy papers.

Sitting, as he believes, at the end of the world, Alexander asks himself: What more can I possess? One would like to reply to him: a telephone, a wristwatch, and a wireless set. Without defeat there exists no sure fame. It is through defeat that Christ makes his presence felt. A traitor enables him to win the battle; a traitor brought Napoleon down.

With what sadness this Alexander would fill us, stuffed full with success as his corpse will be stuffed full of honey by the women embalmers, this Alexander who was served by all kinds of good luck (his urine had the scent of violets), if Klaus Mann did not reveal him as weak, trying to please, taking the wrong route, killing his friend, witness and dear obstacle, and losing from that moment his only excuse for pride.

We shall see him punished by everything which warps him, punished by his marriage with the Queen of the Amazons, punished by his raids and the hatred he arouses, punished by the revolt of the pages, punished by that journey to the void until the reappearance of his love in the surprising and magnificent form of a supernatural creature who watches for his last sigh, to reveal to him, better than the Sphinx, and laughing at his surprise, the word which expresses the mystery of human existence and the purpose of life; a word which is too simple for the ear of a prince to hear, a purpose too near to tempt his hand.

I am happy to place a token of that friendship, which works that are only worthy of admiration cannot obtain, at the front of the book of one of my compatriots – I mean of a young man who is ill at ease living in this world and speaks without inane words the dialect of the heart.

– Jean Cocteau, 1931

Introduction to the first edition

Alexander the Great hardly needs an introduction, but Klaus Mann is scarcely known nowadays outside his native Germany, except among a few devotees. Nevertheless he should be, and not just because he was one of the multi-talented offspring of that giant of early-twentieth-century literature, Thomas Mann (Klaus’s sister Erika became an actress and his brother Golo, a leading historian). He wrote in a different vein to his father and with different concerns, not least because of his more openly gay lifestyle; Thomas Mann had always sublimated that side of himself in his works. Many of Klaus’s writings imply critiques of the societies in which they are set without being explicitly political (unlike the works of his uncle Heinrich Mann, most famous internationally through the film version of one of his novels, The Blue Angel). Klaus was to explore issues of sexual identity, corruption, hypocrisy and the self-destructive nature of genius more frankly than any other member of his family, with what might nowadays be described as a postmodern sensitivity.

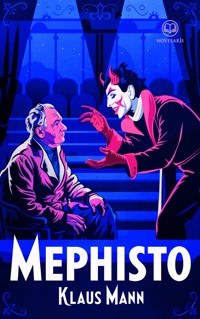

He was born in 1906 as the oldest son of Thomas and Katia Mann and was already writing poems and novellas as a schoolboy. In 1925 he founded a theatre group in Berlin with his sister Erika, Pamela Wedekind, the daughter of the famous dramatist Frank Wedekind, and the actor Gustav Gründgens, who was to become the leading interpreter of the great classic roles in German drama, including, for example, Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust, and was also to feature under an alias in Klaus’s famous novel about Nazi Germany, Mephisto (1936). Klaus also managed to gain for himself some notoriety with his own early plays. Then in 1929 he set off with his sister on a trip round the world, financing everything through lectures and performances on the way.

Klaus Mann’s first novel was The Pious Dance (Der Fromme Tanz, 1925). It was one of the first novels in Germany to deal openly with homosexuality; and its appearance inspired his father to write an essay On Marriage, in which he condemned homoeroticism. In his second novel he explored the complexity of human sexuality more thoroughly in relation to political idealism, and more especially to the imperial dream. Its focus on analysis of the close relationship between failure in human relationships with failure to realise impossible ideals (total knowledge and total control of a world, in which nevertheless freedom and love are able to flourish) is indicated by its subtitle: Alexander. A Novel of Utopia (Alexander. Roman der Utopie, 1929).

On its first publication the novel did not meet with much critical acclaim. The world was not ready for a revaluation of the greatest of the Macedonian conquerors which included descriptions of his private life in such intimate detail. Re-reading the novel in later years, Klaus himself commented that he found it ‘naive and cheeky’. He was doing himself an injustice, however, for in the work he had respected the known historical facts, and his imaginative elaborations on the personal relations together with discussions on strategy are compatible with them. He had studied several of the sources thoroughly, including Aristotle and Plutarch, and the classic nineteenth-century German history of Alexander, the History of Alexander the Great, 1833, by Johann Gustav Droysen, which idealised power in accordance with a Hegelian concept of history.

The first part of the novel develops the image of Alexander as the glorious liberator, the beautiful young man, whom all adore and who can do no wrong, but progressively Alexander becomes a hollow man, estranged from those who would love him. A series of rejections, starting with that by his boyhood companion Clitus, who later becomes one of his generals, leads Alexander to attempt to compensate, overcompensate in fact, for his perceived inadequacies in a headlong, lifelong pursuit of empire. If individuals cannot and will not love him, then whole peoples shall. His initial success is very much due to the fact that he is liberating many countries from the cruel yoke of the Persian empire under Darius Codomannus, and after every victory he is welcomed with the love and adoration he craves, but by the time he has dragged his armies through Bactria, Sogdiana and over the Hindu Kush into India, he is hated by all the races he conquers: he is no longer a panacea but a plague. It might be argued that Mann is simplifying the motivation of a great man, reducing it to a matter of unsatisfied love, but, as his friend Jean Cocteau writes in his Preface to the first French edition, the conflicts of childhood can influence one’s personality for the rest of one’s life: one should not despise ‘those battles in which a snowball can leave its mark on us forever and can forever dry up the springs of the heart’.

The ending of the novel can be understood from a Christian perspective. In his final hallucinatory state Alexander communes with an archangel, who at one point seems to resemble the young blond soldier who had never wavered in his devotion to Alexander. It becomes clear that Alexander has misconceived the nature of love. He had actually killed Clitus, when the latter, acting as a kind of court jester, had revealed to the king the inadequacy of his capacity for love, through a retelling of the epic love of Gilgamesh for the youth Enkidu. Finally too Alexander fails, from a false sense of priorities, to come in time to the deathbed of the one man, Hephaestion, who truly loved and understood him. The archangel, out of concern more than anger, points out to Alexander his basic error: ‘You have sacrificed another, not yourself.’ He promises Alexander however that he will be able to return in another form. The implication is clearly that it will be in the form of one who knows that he must sacrifice himself. It cannot be incidental that at his first encounter with the archangel, Alexander wounded him in both hands. Another was to come later who would himself finally be wounded in both hands.

An intriguing part of the novel is the penultimate section, entitled ‘Temptation’ (the German word ‘Verführung’ can also suggest the act of seduction, but I felt the latter rendering to be too sexually specific in its connotations). In his unquenchable thirst for knowledge about all things Alexander becomes fascinated by Indian mysticism and seeks wisdom through three old wise men who chant to him mysteriously and hypnotically about the nature of Brahman, the ultimate reality underlying all phenomena according to Hindu scriptures. He is tempted and succumbs, almost losing his self in the process, but finally manages to tear himself away from them, with an unfeeling disregard for nature in his flight. Shortly after this the Indian queen Kandake tempts him into loss of self by other means, through a narcotically induced state but also through sexual seduction, until he loses all will power. His life is threatened and he has to be saved by another. When he recovers from these experiences his self-reliance and determination have only been strengthened the more. As ever, Alexander recovers from weakness and defeat through exertion of will.

It is timely to reconsider Klaus Mann’s account of Alexander’s life, which has been the subject in recent years of a television documentary and a Hollywood film. There have of course been other literary treatments, notably Mary Renault’s trilogy: Fire From Heaven (1969), tracing his life from the age of four till his father’s death; The Persian Boy (1972), about Alexander’s campaigns after the conquest of Persia from the perspective of his boy companion Bagoas; and Funeral Games (1981), which focuses on the struggle for succession after Alexander’s death. In general however it must be said that Renault’s account is uncritical and romanticised. More recently there has been another trilogy by the Italian professor of classical archaeology and journalist Valerio Massimo Manfredi. These three volumes were published together in 1998, appearing in English in 2001: Alexander: Child of a Dream, Alexander: The Sands of Ammon, and Alexander: The Ends of the Earth. While being historically sound the works do not explore Alexander’s emotional life deeply, downplaying the gay element; emotions are described but not analysed. The film Alexander the Great (1956) directed by Robert Rossen, suffers from the rather wooden, respectful style with which epic subjects were treated in the period. There is much careful grouping of figures and big set speeches in theatrical style. There is not a hint of anything untoward in Alexander’s sexual proclivities in Richard Burton’s portrayal of the king, and he failed to hide approaching middle age convincingly under his blond wig. A more recent version of the story, Oliver Stone’s Alexander (2004), with Colin Farrell as the king, explores the close relationship between Alexander and Hephaestion more frankly, but is still a little coy in handling it. In an interview with The Guardian (August 10, 2007), concerning the director’s final cut of the film, Stone stressed that the Warner Bros studio wanted him to ‘cut out all the homosexuality and everything that reeks of anything incestuous’. He did try to keep them happy by including scenes with Alexander and his wife Roxana making love (which the king never manages to achieve in Mann’s version). In Stone’s words: ‘He had to father some kind of heir, but he didn’t work too hard at it did he?’

A stimulating account of Alexander’s life and an evocation of just how strenuous his campaigns were are provided by the historian Michael Wood’s three-part documentary In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great (1998). Wood constantly crosschecks legend with the major historical sources in the earliest biographies, especially those of Plutarch, Arrian, and Curtius (Quintus Curtius Rufus), whose History of Alexander proves to be stimulating and evocative. In an interview included on the DVD of the documentary Wood also points out that Alexander’s hatred of his father and close relationship to his mother invite a psychoanalytic interpretation of his obsession with conquest: ‘There’s clearly something heavily Freudian going on in all this.’ But later he adds: ‘The Freudian thing… no one has got to the bottom of it.’ Except perhaps Klaus Mann? Mann’s Alexander fits closely Wood’s description of him as ‘broken in the end by the loneliness and insecurity of absolute power’.

There are countless Greek personal names and Greek versions of place names in Mann’s novel. Fortunately the author generally identifies the characters by their military role, or relation to Alexander, so that it is not necessary to burden this edition with copious notes. Listing modern geographical equivalents to the names of places, rivers, and cities etc. would also unduly increase the weight and price of the present volume. The notes therefore only include a few clarifications which aid easy reading. Readers who are keen to track down references in more detail are referred to the excellent glossaries, indexes and maps in some editions of Curtius’ history. For the transliteration of the Greek names I have followed the English conventions rather than rely on the German renderings. Klaus Mann occasionally switches tenses abruptly and I have incorporated this in my translation when it does not lead to confusion in English. His style is also a blend of formal, poetic and at times even flowery elements with occasional colloquialisms; I have endeavoured to reflect this as faithfully as possible in English.

Finally I owe a great debt of gratitude to those friends who have helped me to resolve ambiguities and obscurities in the German text and in Cocteau’s Foreword. They are, in alphabetical order, Benjamin Barthold, Philippe Blanvillain, Alan Miles and Philip Morris. I am also very grateful to Katherine Venn and Rebecca Morris for all their practical advice.

– David Carter, 2007

Introduction to the second edition

It is always gratifying to learn that a book is going into its second edition, not only for the author of course, if he is still alive, but also for the translator. In the case of Klaus Mann’s novel Alexander. A Novel of Utopia, it reassures me especially, as its translator, that my efforts have been recognised and appreciated, and that I have managed to reconcile reasonably well the requirements imposed by those often conflicting ideals that hover in the mind of every translator: faithfulness to the text and naturalness of rendering.

The appearance of a second edition also signifies that it has been read by many and found to be worthy of a wider audience. One of the reasons for this is undoubtedly that the author has clearly discovered and thrown light on aspects of Alexander’s personality that most others before him and many after him failed to explore adequately. They were unable to provide such a coherent and convincing account of the relationship between Alexander’s sexuality and his unstoppable drive for conquest. As indicated in the Introduction to the First Edition, Mann perceived the important influence on Alexander’s development of his hatred for his coarse, power-seeking father and of the mystical power exerted over him by his mother. Mann also shows how the experience of being rejected in love as a child can shape one’s motivations throughout life.

On re-reading the novel and Cocteau’s Foreword in my own translations I find no reasons to modify any of the opinions expressed in the first Introduction. Nine years have passed, and coming to the novel again with a fresh view, I have become aware of it more clearly in its broader historical and social context, both as a novel published in Germany in 1929 and as a work being reprinted in the UK in 2016. In the Weimar Republic same-sex love between men was a crime, and had been so since 1871. According to paragraph 175 of the penal code as it stood at that time, unnatural intercourse between men was punishable with a prison sentence and could lead to the loss of citizen’s rights. While more enlightened views on homosexuality were spreading among intellectuals in general and writers and filmmakers in particular, public perception of it had not noticeably changed. And in 1931–32, only a few years after the publication of the novel, the leading Nazi Ernst Röhm was to be hounded by the Social-Democratic Party (the SPD) as a ‘175 Man’ (i.e. as one who could be categorised according to that paragraph). It is uncanny too that within a few years of the appearance of Mann’s vision of an idealized and worshipped leader, loved and adored by all, but who ends up being hated and despised by all, the German Führer should be pursuing his own megalomaniac drive for conquest on the strength of a personality cult.

It should not be forgotten, in 2016, that demagogues succeed not by rational argument but by their very charisma and passionate commitment and by their ability to play on the insecurities and anxieties of the masses. Evidence of their presence and influence in today’s world is not hard to find, and the reader will be able to identify such personalities both in the West and in the East, and indeed in many countries, both great and small, that lie between. In this respect the novel can be read as a cautionary tale.

– David Carter, 2016

The Empire of Alexander the Great

‘The man who had appeared to the country as a bringer of freedom and as a much-loved saviour now came as nothing other than an affliction…’

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France

Alexander

Awakening

1

There were the sun, enchanted animals and swiftly flowing waters. Concerning the animals Alexander knew that the souls of the deceased dwelt in them, and that it was better to handle this little dog and that little donkey gently, for perhaps they might be your grandfather transformed. And in the ripples of the brooks and the mountain rivers there also dwelt beings, which were mysterious, but so loveable as well, that you could listen to them for hours, when they joked around, danced and burbled away. Similar beings lived in the trees and bushes, and especially charming little ones in the flowers, which one was not allowed to pick for that reason.

Life was completely beautiful, as long as the father stayed in the background. This he did for the most part, and he only talked with the child on festive occasions, during which he liked to tease it in a rough way. The child did not cry, but looked at the bearded man, who was roaring with laughter, in a piercing way. But the man did not notice how full of hate and angry the child’s look was.

Everything seemed good, even the mother’s snakes, and it was only the father whom he rejected. Why did the father laugh in such an unpleasant way, and if you did not laugh with him, he became sullen. It smelt of sweat and alcohol when you were close to him, but of herbs and her beautiful hair close to the mother.

Leonidas, who called himself a pedagogue, although he was at best an attendant, was a good person, even if he did hawk and let wind as well; and Landike, the stout and asthmatic wet nurse, was also a good person. The way she staggered around, with her kind-hearted face! It was comfortable being with her, and her bosom, which rose and fell in a friendly way, was a refuge, which you could rely on. Her stories were not so marvellous as those of the mother, but they touched your heart. Landike told of the vine made of gold with emerald grapes, of the golden river and the Sun Well,1 and of all kinds of adventures, pranks and foolish behaviour of the lesser and the medium level gods, but she did not dare to touch on the great gods, for she had a reverent attitude.

But when the mother told a story, the rest of the world sunk out of sight, and there remained only her deep, evenly rumbling voice.

It was rare indeed that Olympias spoke, for she mostly remained silent, and looked in an unfathomable way from beneath her stubbornly lowered brow. Characteristic of this look, which, under the long pointed eyelashes, was profoundly mocking, was an uncanny force drawing you in, and it was both impassioned and ice cold. Also very disturbing was her mouth, a large mouth, with thin, strongly curved lips, reminding you of the mouth of a lion at rest. Her hair, which she wore short, was shaggy and curly, and her neglected, slender hands had something wild and predatory about them. Many considered the queen to be very stupid, but then others thought she was mentally disturbed. She was completely inaccessible to logical consideration and was stubbornly dogmatic to the point of blindness. As she was known to be hot-tempered and even brutal, nobody dared to contradict her; many, who had nevertheless risked it, had felt her hand on their face, making it burn. Even Philip was familiar with these well-aimed boxes round the ears.

Most of the time she was silent, sitting there and brooding, and at most she mumbled gloomily that she was tired. The whole court discussed what forces she kept company with at midnight. Why was she so exhausted during the daytime? Because at night she conjured up the most evil spirits. That was more indecent than if she had deceived Philip with a mortal. Egyptian priests and Babylonian magicians had initiated her into the most dubious secret cults, and she definitely knew more about Orpheus and Dionysus than was proper. What did she get up to with all those snakes, which lived in baskets near her bed? There was no end of gossip about that.

Whenever she was in a good mood as evening approached, she let the young prince Alexander come to her. She kissed and pressed him passionately, and he became dizzy when he breathed the smell of her hair, which had a bitter overpowering quality. She looked up at him in an impassioned and mocking way, and then began suddenly to tell a story, interrupting herself as she did so with little bursts of timid laughter and also putting her bony hand to her forehead in a pointless way.

Again and again she felt impelled to tell the story of Orpheus, who was torn apart by the maenads. They tore him into tiny pieces, because they loved him and were drunk, but he, since the loss of his Eurydice, did not like any women any more. It was the nine muses, who, wailing, gathered together his bloody parts and buried them on a beautiful mountain. Olympias sang with her booming voice the songs, which were by Orpheus, and then her child felt more solemn than when at prayer. She hummed and droned and shook her head with its unruly hair, and even if Alexander was already crying, she went on humming and droning. ‘It’s the harmony which makes you cry,’ she said, teaching him in a dreamy way. ‘In the same way I, as a child, cried about the circling figures in the stars…’

Somehow related to the story of Orpheus, but even more mysterious in its way, was the Egyptian fairy tale of the divine King Osiris, killed by his brother Typhon, who was as cunning as he was evil. How he set about it was horrifying and complicated. For he had a chest specially made, which had exactly the same noble proportions as Osiris. After doing this he pretended, with his friends, among whom was his guileless brother, that he wanted to try out a game, the senselessness of which should have been obvious: for each of the companions was to lay himself in the box, until the one was found who fitted in most exactly. Of course nobody fitted in, except Osiris, and then they closed the lid on him. Those horrible men threw him into the river, so that his corpse would flow into the ocean. Washed up on a wooded bank, he was found by Isis, who was lover, sister and mother to him, and who was searching for him most devotedly. She nursed, adorned and caressed the poor body of her sweet spouse, but hardly had she left him alone, to see her little son Horus, than Typhon seized the royal corpse and cut it into fourteen pieces.

Mysteriously intertwined with the story of the royal god Osiris was that of Tammuz, who had lorded it in Babylon, and of the handsomely built Adonis, known in Asia Minor. All of these spilled their blood, and all of them were lamented by their mothers-cumlovers, who were called Isis, Ashtar, Astarte or Cybele.

‘God has to be killed.’ With this the Queen finished her fairy tale with sensual cruelty, laughing in a horrible way and putting her hand to her forehead in a meaningless way.

Alexander listened to her with fearful interest; he was already dreaming of the bodies cut up into pieces. With profound cunning and scheming Olympias awoke horror in him and made his teeth chatter with fear. So much more wonderful did the effect, which followed, seem.

For cutting up the god into pieces was the condition for the miracle of his resurrection; the misery had to have been great, so that the rejoicing might be endless.

Though the women had wept for a long time over their Tammuz, or Adonis, and beaten their breasts, he came again, and revealed himself to them in his second and truly alive state. Olympias grasped the wrist of her son who was trembling with fear, and thus they stared together at the bloody parts of the body, which had been torn to shreds, and still seemed to twitch a little. Now they also began to weep, with the mourning women who were rocking themselves to and fro, with a noiseless but urgent chant of misery. They stared with eyes already blinded by tears at the place where the dead man was lying in his blessed blood, and sang, sobbed and rocked to and fro in the dance. Not until they had wept for a long time and beaten themselves, did they partake of happiness; at last the Lost One came again; in great glory the Decimated One stood there, and his was the splendour, the power and utter magnificence.

So Demeter was happy every year when the lost daughter returned in health. Olympias also told her story to her enchanted son. ‘I am her priestess,’ she whispered, with her hand covering her mouth, ‘I served her on Samothrace and experienced it all –’

She revealed to her child and only to him, what she knew: the mystery of the bloody sacrifice and the resurrection in the light.

From when did it become clear that the grey Landike, swinging to and fro, disappeared in a twilight of gentle shadows? When did it suddenly become clear that that tottering gentleman Leonidas was not to be taken seriously, and that one was permitted to laugh when he gave a little cough and put on airs? The awakening came, without his being aware of it, gradually.

A decisive outward change came when he moved into the men’s quarters. The child was removed from the provocative influence of Olympias, and only on festive occasions was the mother allowed to see him and caress him. Admittedly Philip also kept in the background temporarily, being occupied with political affairs. What is more children did not interest him, and he decided not to concern himself personally with Alexander, until the boy was fifteen years old. At this time he was not yet thirteen.

Philip trusted his Greek teachers. They were sophisticated and skilful men who always had a proper smile at their disposal. As he paid them well, the king thought that they must also be able. They promised to introduce the prince to the basic principles of mathematics, and to provide him with some knowledge of rhetoric and history; he should even learn to play the lyre.

His Highness was so gifted, the well-paid men asserted flatteringly to the king, that he should naturally lack nothing. Among themselves they mocked the barbarian Philip, who worshipped their culture like a parvenu, but the latter, it could not be denied, had been blessed by the gods with a fatal talent for political intrigue. There was not yet any trace of that in the crown prince, and the Greek teachers doubted very much if it would ever manifest itself in him

For this boy was decidedly backward for his years. So much reserve was not possible: he must be lacking in talent. Admittedly he was not completely without grace, but it was an awkward grace, that of a disabled person, which had something not manly, not energetic about it. Only his eyes puzzled even the teachers. Beneath the high-vaulted black curves of his brows, which gave the effect of being constantly raised, with even his forehead seeming to wrinkle easily, those eyes had a strangely dilated, bright and seductive look. It was the magically urgent look of his mother, but not at all soft, like the night, and vague, and also actually not at all mocking. Rather, it was sharp, scrutinising and of a steely grey. Unfortunately this grey had the disturbing quality of turning into a blackish and even into a blackish-violet colour, indeed in such a way, that the colour of one eye became intensively darker than that of the other. Then the face of this happy and gentle boy, who still played for hours, kind and solitary, with flowers or small animals, acquired something that almost aroused fear; Around the gentle mouth which had the sweetness of immaturity, muscles played, which led one to expect the most dangerous things later in life.

As friends and for close companionship for the prince some boys from the high levels of Macedonian aristocracy had been selected. Among these were Clitus and Hephaestion.

Alexander, Clitus and Hephaestion were mostly kept separate from the others, and only at mealtimes, during lessons and the obligatory games did they meet up with them.

However matters were complicated between the three of them, or, more precisely, between Alexander and Clitus, and it was the gentle Hephaestion who had to suffer from this. While Alexander and Clitus seemed to be fencing with each other in silent conflicts, Hephaestion remained a neutral mediator, gentle, agreeable and with the same tenderness towards both. His beautiful dark face was a little too large and too serious for his age, with a wonderfully shaped mouth, a noble brow and a fine solemn way of looking. Only where his cheeks were did it seem a little too shallow, not completely filled out, not alive in every muscle. Hephaestion had a touching and loveably complicated way of bowing, and he did it extensively, not without a roguish grandeur and with the hint of a smile. When he parted his lips, his teeth glistened with bluish enamel.

Clitus on the other hand seemed to be alarmingly childlike. In his soft cheeks there was almost always a laugh. His small, straight nose, which was very narrow at the base, broadened like that of a baby at the tip. His hair fell down over a low and bright brow; below his evenly drawn out long black eyebrows his cheerful eyes had a lively and confusingly shimmering language of their own.

In the games of his imagination the most outrageous things happened. The immortals came to him, and Clitus celebrated marriage with all the goddesses of Olympus. In between jokes and tall stories he quoted philosophers. Although it did not seem to suit him, he knew quite a lot.

He hated being touched, and shunned and despised caresses. As though his skin were oversensitive, he shuddered if someone stroked his loose-hanging hair. He did not regard lust highly, and mocked Alexander and Hephaestion when they yielded to it. The air in which he lived was purer than that in which others thrive. He was vain about his beauty, and loved and admired his image passionately, wherever it presented itself to him in mirrors or in stretches of water. But he scoffed at and ill-treated those who loved him for the sake of his beauty.

His self-confidence seemed to be brilliant and hard like a jewel. He allowed himself to make little jokes about his genius and the prettiness he was blessed with, and boasted, lied, and made-up stories. He laughed and made clumsy little movements with his hands. But he mocked those who had really achieved something: Antipatros, Parmenion, all the grey-haired dignitaries and generals were the object of his impudent and swift comments. Without having the need for recognition, he indulged himself deeply on his own in dreams of enterprise, which never amounted to anything, but he just planned things and had fun.

Alexander thought that, compared with Clitus, he himself was becoming problematic and clumsy. What was developing behind his own brow was dull, confused and questionable; but in Clitus everything seemed to be magically ordered. When Alexander imagined Clitus’ thoughts, he had an incomparably lovely vision, which evoked his envy, of geometrically arranged dancing figures. Which criss-crossed each other in effortless clarity. But in him however, in Alexander, there was a dark struggle and conflict.

Although Clitus, as was necessary according to custom and a sense of tact, behaved very politely and even humbly towards the prince, the latter nevertheless always believed he could sense his half amused, half inexplicably serious aggression. To over-come this aggression, and to win the child over, who remained inaccessible in his isolation, became the sole and burning ambition of Alexander. It went so far, that he found himself being the wooer of this boy. For two years he had only one goal: to conquer him! He had decided irreversibly in his heart: if anyone can be my lifelong companion, it is he. I want only one friend: this one. He is preordained for me, Alexander thought with blind and impassioned stubbornness. I want him, I must have him. It shall be my first, my most important conquest. – But Clitus evaded him.

Standing wistfully to one side was Hephaestion. He could understand the situation with melancholy clarity, but was silently content with the fact that he was the third person who was able to mediate between them and reconcile them. Often, when Alexander was at his wit’s end, he found consolation in the always ready intimacy of the faithful Hephaestion, who renounced without ever having possessed. He knew that there would never be any other human being in his life apart from Alexander. But with a sad, secret pride, he also knew, that Alexander needed him, that he was necessary and irreplaceable to him.

Alexander was driven to provoke a decision, the necessary outcome of which was clear to him in his heart. Thus he stood one night in the room, narrow and bare like a cell, which was Clitus’ bedroom. It was winter and icy cold. Alexander had only put a light cloth over himself quickly, and thus he stood in the doorway shivering. Clitus hardly gave a glance in his direction. He was lying calmly on his back, looking steadfastly at the ceiling.

That face was almost always seen to be laughing, so it was much more remarkable therefore to find it suddenly deadly serious. Above all the cheerful eyes had changed, and the pupils seemed to have become broader and blacker. Alexander, as though paralysed with shyness, sat down by him on the edge of his bed. Clitus remained motionless. ‘I’m looking at one spot,’ he said in a harsh tone. ‘I’m waiting till it moves.’ ‘Do you want it to move then?’ Alexander asked him softly, and it seemed to him that he was watching, very much without permission, a very secret and forbidden game. ‘I don’t want it to’ replied Clitus, just as softly but much more clearly. ‘Someone else wants it to. Someone inside me. But I don’t know him.’ And he kept cruelly silent. Alexander crouched by his bed, his teeth chattering with the frost. Nevertheless he devoured with his eyes this stony, empty chamber with an incomparable tenderness: the poor bed and on the bed the child, the contours of whose body stood out under the thin blanket. As he could not bear any silence he finally asked again: ‘Is it moving now?’ He lay his face on Clitus’ pillow, so that his hair came close to Clitus’ cheek. ‘You’re disturbing me very much,’ said Clitus, without looking at him.

At this merciless reply Alexander started as at a judgement passed on him. He knew that at that moment a decision affecting his whole life had been uttered. He believed it was in order for him to weep, but he just trembled. Now he did not even dare anymore to ask the other for a corner of his blanket.

Suddenly, with a voice full of jubilation, Clitus shouted: ‘They’re moving – Oh!’ He told the other hastily, his eyes radiant with happiness: ‘You see, I’ve been aiming at two of them. If they collide, there’ll be a disaster! I’m so pleased! – Bang! Hey, that was some noise – ‘ He became silent and was shattered. As after a great effort he closed his eyes.

Alexander stayed, although the most natural sense of honour required that he should go. He did not dare to move any more, for fear of disturbing the other, inexorably silent, in his adventures. He felt himself further removed from this strict dreamer than from another star. Nevertheless he stayed: he could not find the strength to go. His last thought was that it was all the same to him. Indeed he did not even dare to meet Clitus’ look any more. And so he buried his face in his hands.