Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

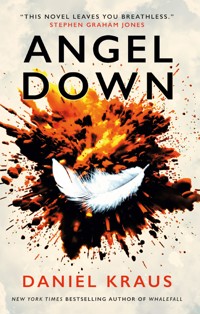

A stylistically bold and innovative, cinematic horror novel about greed and paranoia, set amongst the grit and mud of the trenches in WW1. Perfect for fans of Stephen Graham Jones and Alma Katsu. From the New York Times bestselling author of Whalefall, and the co-author of The Shape of Water alongside Guillermo del Toro. Private Cyril Bagger has managed to survive the unspeakable horrors of the Great War through his wits and deception, swindling fellow soldiers at every opportunity. But his survival instincts are put to the ultimate test when he and four other grunts are given a deadly mission: venture into the perilous No Man's Land to euthanize a wounded comrade. What they find amid the ruined battlefield, however, is not a man in need of mercy but a fallen angel, seemingly struck down by artillery fire. This celestial being may hold the key to ending the brutal conflict, but only if the soldiers can suppress their individual desires and work together. As jealousy, greed, and paranoia take hold, the group is torn apart by their inner demons, threatening to turn their angelic encounter into a descent into hell. Angel Down plunges you into the heart of World War I and weaves a polyphonic tale of survival, supernatural wonder, and moral conflict.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 344

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Élan

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

The Gaff

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

XXX

XXXI

XXXII

XXXIII

Mercy Seat

XXXIV

XXXV

XXXVI

XXXVII

XXXVIII

XXXIX

XL

XLI

XLII

XLIII

XLIV

Acknowledgments

About the Author

PASTE MAGAZINE MOSTANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2025

GOODREADS MOSTANTICIPATED BOOKS OF 2025

“A searing, frenzied, and haunting reminder that the horrors we most often face are the ones we create ourselves.” P. Djèlí Clark

“This novel leaves you breathless. You can’t guess where it’s going, or how it’s going to get there. Just, let it take your hand, pull you through these trenches, this war, this century, this… this life.” Stephen Graham Jones

“A literary masterwork of unparalleled dexterity and ingenuity. One of the best things I’ve ever read. I’m absolutely blown away.” Josh Malerman

“A masterpiece.” Ally Wilkes

“The highest level of literary ambition, and the most gripping, unforgettable account of war in recent memory. American war fiction will be haunted by this book for years to come.” John Milas

“An absolute revelation, a hymn that sings of the humanity found within history’s horrors. Here is a novel that will restore your faith in what the written word is capable of capturing.” Clay McLeod Chapman

“A brilliant novel that will encourage its readers to live their best lives, despite the horrors that surround them.” Booklist

“Relentless. Kraus ramps up the tension with the relentless cadence of his prose… With this vigorous narrative, Kraus breathes new life into the war novel.” Publishers Weekly

“An undeniable masterpiece.” Capes & Tights

“Disorienting and utterly sublime. This book is a miracle.” Eric LaRocca

Also by Daniel Krausand available from Titan Books

Blood Sugar

Pay the Piper

(with George A. Romero)

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Angel Down

Print edition ISBN: 9781835415382

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835415399

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: July 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Daniel Kraus 2025

Daniel Kraus asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Typeset by Richard Mason.

Dedicated toMICHAEL RYZY,BROTHER-IN-ARMS.

But they are hideous creatures—degraded beasts of a lower order. How could you speak the language of beasts?

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS,The Son of Tarzan

ÉLAN

I

and Cyril Bagger considers himself lucky, he ought to be topped off, gone west, bumped, clicked it, pushing daisies, a new landowner, napooed, just plain dead, not only dead but scattered around in globs, for the last thing he saw was a shell dropping on top of him with the noise of colliding freight trains, a jim-dandy of a shot from Fritzy the Hun, and kind of ironic, seeing how the whole reason Bagger prefers burial duty is artillery shells can’t reach this far behind the frontline trench, but this shell sure did, the way he always pictures it in dreams, a red skull of fire screaming down, giving him one second to think, That old Bagger luck has finally run out,

and the afterlife, for the brief time he knew it, had been delectable, he was gentled back into the arms, and the long, long legs, of Marie-Louise, the prostituée on whom he’d lavished all his francs when the Butcher Birds of the 43rd had been stationed in Vosges, pretty, dry, warm, quiet,

bloodless Vosges, where every inhale was Marie-Louise’s La Rose Jacqueminot parfum, her rosewater hair and periwinkle powders, every exhale the flutter of her dyed red hair and the lace whatchamacallits of her lingerie, and so the last thing he wants is someone fucking with him and demanding, “You alive?,” to which Bagger responds, “Fuck no,” to which the man laughs mirthlessly and pulls him up by the armpits like a breech birth, so Bagger the newborn unseals his eyelids, a crust of mud, oil, and embarrassing tears, and discovers he’s being lifted from the burial pit he’d been digging when the mortar hit, now blown to triple its size and is stacked with triple the dead, all being sprayed with quicklime and hastily carpeted in soil,

and Bagger would have been buried alive if not for this sharp-eyed private, he really ought to reward him with a cigarette, but Bagger’s distracted by the corpses packed slick hot on all sides of him, one dead doughboy nearly beheaded by a pelvic bone, another who bit it collecting his intestines in one of his boots, a third stomped so flat by a shell that his spinal column protrudes from his gaping mouth,

and yet Bagger, by his own baffled accounting, is intact all the way down to his little piggies, so how the fuck is he alive when everyone who’d been near him, by the look of it, was exploded, shredded, and scattered, he tries to credit the corpse he’d been carrying, it must have absorbed the shrapnel, but a nagging voice insists it’s a miracle, which only pisses him off, he’ll be goddamned if he’s going to start believing in miracles here in hell,

and once his ass is on solid ground, more or less, he realizes this marshy patch of land between the Argonne Forest and River Meuse has fallen quiet, and there’s nothing more suspicious, a Western Front quiet is tetchy, one side always gets itchy and opts to bleed a few hundred more men over a few inches of land so ruined only a maniac would want it,

and so Bagger sits up with vision aswirl and shoos away the filthy pelt of air, the pigeon-gray smoke and eyeball-white fog, and beyond the hills of diarrheal mud and the pappy craters from whence those hills were upchucked, Bagger sees trucks and carts and wheeled guns crunching east, looks like the whole fucking U.S. First Army, III Corps, 43rd Division has vacated the scene with the likely exception of Bagger’s lowly Company P, forever dangled like a gonorrheal dick from the brigade’s leftmost flank,

and Bagger feels for his haversack, still there, and extracts his Bible, and opens it, and stuffs his nose into the gutter, and inhales, doesn’t give a fuck about kings and shepherds and carpenters and prophets, but the damp protean smell of the book’s red leather and the woody scratch of its onionskin pages, each one half-mooned by his father’s finger-stains, has a smelling-salt effect on Bagger, has since he was a kid, it brings him back to the cramped study over the church where Bishop Bernard Bagger labored on sermons, back when Cyril’s heart, now filled with smoke, was filled with what must have been hope,

and it’s only through the motions of inhaling that Bagger feels a brittle tightness, his face is glazed in dried blood, clearly not his own, and he orders himself not to imagine whose, it’s best when blood has no deeper meaning than rain, especially in the Argonne where so few trees remain to block the October wind that flash-dries blood so rapidly to your skin,

and while there’s no telling which boy bled this blood, what kind of blood is a different matter, fourteen days into this cyclone of cartilage and lead, Bagger has developed a sommelier palate for the tart fizz of brachial blood, the fudgy sorghum of femoral, the meaty sludge of heart wounds, the rancid reek of any gut juice at all, and the warm salt lick of arterial blood he now licks from his lips,

and it’s good the Bible is here to push him through it, Bagger takes a loud, greedy sniff, sinuses bathed in the aromatic nostalgia of comfort and solace, then reluctantly pockets the book and sticks fingers into his ear holes to clear out the creamy plugs of mud and blood, in this trenchworld hearing is so much more vital than seeing,

* * *

and the world’s noises whoosh back, and Bagger catches his breath at a rubbery wail that overrides everything, another minenwerfer dropping, the same kind of shell that ripped his fellow buriers to cutlets, oh no, oh shit, but hold on, wait, no, this is different, less a wail than a shriek, no rival to a minnie on a decibel level but with an edge that chisels through the end-times grumble at a pitch he’s never heard,

and though there’s plenty of attack machines in extremis out in No Man’s Land, their death moans are as predictable as hinges, while this shriek is organic, as alive as Marie-Louise’s pleased moans or Bishop Bagger’s stentorian damnations, it could be male or female, human or animal, but whatever it is, it’s dying, dying slow, dying loud, ripple after glissading ripple of agonized lament,

and Bagger, already weighed down in mud and blood, further heavies in the dreary certainty that the shriek won’t ever end, just like the war won’t ever end, like the carnage won’t ever end, it’s a sentence in a book careening without periods, gasping with too many commas, a sentence that, once begun, can’t ever be stopped, a sentence doomed to loop back on itself to form a terrible black wheel that, sooner or later, will drag each and every person to their grave,

II

and Bagger wipes his face with his forearm and five pounds of matter plop off his head, his brains, he supposes, all that blood on his face was his after all, and because he’s become educated in what brains look like, he stares into his lap for confirmation but all he sees is yellow clay, there’s nothing more ordinary than yellow clay in the Argonne,

and while he’s staring at the claybrains, he notices a voice,

and the voice feels like part of the shriek, an undertone,

and Bagger knows undertones, he grew up enveloped in the poly-phony of the church’s old pipe organ, the Swell, the Choir, and the Great woven like flutes, strings, and reeds, but this undertone is from a yet uninvented keyboard called voice,

and the voice says, Bagger,

* * *

and it’s stimulating how the word seems to buzz from within his own flesh, that’s how it felt when standing beneath the sanctuary pipes, though Bishop Bagger would have told little Cyril that’s only guilt murmuring from inside you, a sentiment the adult Cyril Bagger refuses to buy, he’s worked too long to bury such weepy notions along with the hundreds of dead bodies,

and so he ignores the voice, it’s just his skeleton vibrating from the mortar strike, and takes a big, fetid inhale, all right, Bagger, your division’s on the march, not good, but otherwise things are as you left them, which is to say absolute shit, Jerry’s shells have slashed a half-mile cleft through the trench system’s doglegs so that front, support, and reserve trenches all reside under a fourth designation called smithereens,

and within those smithereens Bagger verifies that Company P indeed lingers, there’s Lieutenant Aquila’s gorilla limp, there’s Sergeant Rasch’s crow caw, but instead of slumped like mutts in post-battle stupor, Company P is on its feet, bumping like windup toys between fat tongues of displaced mud, and Bagger wonders if the shriek is driving them mad, too, damn sure something strange is afoot, and Bagger’s got to goose himself to life if he’s going to outfox it same as he’s outfoxed everything else,

* * *

and so he imagines General John. J. Pershing lording over him, demanding, Where are you, Private?, and he saying, France, sir!, and Pershing saying, More specifically, Private!, and he saying, Bois de Fays, sir, and bois is frog for woods, sir!, and Pershing saying, Very good, Private, and do these look like woods to you?, and he saying, No sir, but they might have been woods a few years ago, sir, before the giant trolls came through, and Pershing saying, And what were those trolls’ names, Private?, and he getting the gruff old army commander to crack a smile by saying, Marne, sir, Verdun, sir, Somme, sir, stomped the shit out of everything, sir,

and Bagger laughs, and it helps more than the Bible, hallelujah, hoist the flag and let her fly, Yankee Doodle, do or die, Private First Class Cyril Bagger feels more like lucky old Bagger again, the Hawkeye Hustler, the Sioux City Sharpie, the Council Bluffs Crossroader, the Dean of Dubuque, nicknames he earned from being banned from half the riverboats on the Mississippi, not that he doesn’t own a tackle box of disguises capable of getting him back on those boats the second he gets home,

and once he’s back in Iowa, he’ll rerun the same schemes, the flop, the ring reward, the pigeon drop, mine salting, pig-in-a-poke, the fake-counterfeiter, he’ll even do a classic melon drop just to prove he still can, hell, before the Army nabbed him, he even toyed with psychic boobery, finagled a metal rod to jut from a hidden leather cuff to make the table seem to rise beneath his hands, a total bust, though he knows the spiritualism con is a growth area, grievers make the best marks and postwar America’s going to be lousy with grievers,

and it’s this same sleight of hand that has kept him safe out here, that and a bacon can packed with dominos, bottle caps for shell games, loaded dice, a pen for drawing pips on sugar cubes in case he loses those dice, and marked cards, and when it’s too dark to read those marks, he razes the card edges with a fingernail he keeps sharp, or puts literal cards up his literal sleeves, there’s always a cornpone private unable to identify him as a shark who has more teeth than Iowa has corn, and those boys bet everything, lives included, when their manhoods are impinged, and here in frogland, challenges to one’s manhood crop up every few seconds,

and the result is soldiers who end up so far in arrears they have to pay back Bagger in derring-do, infantry charges mostly, they go over the top in his place and get on a first-name basis with bullets while Bagger steps back, way back, keeping to latrine and burial duties, where flying lead doesn’t whistle past one’s ears but rather whines like late-summer mosquitoes,

and when he’s not working a shovel, he’s insubordinating in front of every captain, major, lieutenant, and sergeant in the 43rd so they’ll “punish” him with more backline duty,

and by accident, he’s gotten good at those duties, he’s practically become the 2nd Battalion’s burier-in-chief, planting fellow doughboys in the dirt makes him feel like a proper goddamn artiste,

and the idea of other men doing Bagger’s work job while he was briefly unconscious offends him, what does the HQ staff, those signal men, cooks, clerks, quartermasters, bugle boys, and stretcher-bearers, know about burying bodies, nothing, that’s what, the savages probably laid them head-to-head instead of head-to-feet and neglected to cover their faces, and when they came across disarticulated parts, a foot or a head or a perfectly preserved bottom jaw, they probably chucked them in like olives into cocktails, and furthermore, probably failed to note the coordinates of the burial pit, not that it’s worth a crap, no recovery detail is ever coming back to exhume doughboy bodies and everyone knows it,

and, what the hell, there it is again, that voice, Bagger,

and then it’s replaced by something louder, realer, “Bagger! Bagger! There you are, Bagger!” and Bagger’s vertebrae crackle as he swivels his neck to see Lewis Arno dancing around upended oak roots and furry-looking clumps Bagger identifies as moss, only to feel stupidly naive, there was a minnie, there was a burial pit, and that’s not moss, Cyril Bagger, you dumb fuck,

* * *

and Bagger’s guts thicken like they do anytime he sees Arno, the kid’s fourteen, lied about his age to some Nebraska National Guardsfuck trying to make quota, and ever since has been a tick sucked to the 172nd’s underbelly, devoid of skills but too damn small for the Germans to hit, and Bagger resents the kid, really goddamn resents him, the kid complicates Bagger’s otherwise flawless loathing for everyone out here, there’s not even any point in swindling Arno, the kid doesn’t have a penny to his name,

and Bagger also loves seeing Lewis Arno, and there’s nothing he hates more than love, so he snaps, “What do you want? Little trench rat,” and Arno sets aside a Chauchat rifle bigger than him, stares big goose eggs, and whispers, “Are you dead?,” the second time Bagger’s heard this, he must look really goddamn bad, so he snaps, “Yes. I’m a ghost. And I’m going to haunt the fuck out of you,”

and this seems to satisfy Arno, who presses sooty palms over sooty ears and asks, “What’s that noise?,” which gives Bagger some relief, if Arno hears the shriek, it means Bagger’s not loony, he’s not gone 4-F, not yet,

and so he gins up the wildman grin he knows the kid wants to see, and replies, “Sounds like someone’s letting the air out,” and Arno asks, “Of what?,” and Bagger says, “The whole big balloon” with a mad chuckle, though what he imagines is quite sad, the earth, punctured by a 105mm heavy, leaking air, cratering inward, with all of them along for the crash,

and Arno says, “It hurts,” juvenile but accurate, the shriek does hurt, though not the ears, feels more like a small, feminine hand sliding into Bagger’s chest through a shrapnel wound and squeezing his heart arrhythmically, and if he wasn’t already kneeled, he’d have to take the posture, so damn the kid all over again for making the hard parts of him go soft, “You’re bellyaching to the wrong soldier,” Bagger gripes,

and what impresses him about Lewis Arno, from a con man’s perspective, is that the kid’s not easily bluffed, Arno points at him and says, “You got face on your face,” a statement that, at any other time and place would be gibberish, but there’s only one interpretation here, a real unfortunate one, and Bagger gingerly touches his own face, cracking the blood glaze into fragile plates, and Arno grimaces, and Bagger traces the grimace to his own right jaw, where something dangles, slight and flexible like a human ear,

and Bagger peels it off his face and holds it before him, and that’s exactly what it is, a human ear, clotted with clay and matted with a tuft of blond hair,

and he wipes his face of the face, and the only way not to throw up is to make a joke, so he takes the ear by its helix, holds it out to Arno, and says, “Ear you go,”

and the joke lands flat, the kid is appalled, so Bagger tosses the ear over his shoulder, devil-may-care, but he does care, he does, so much he wants to spin around and find the ear and pin it to his lapel, a medal more useful than the Croix de Guerre, one that might lend him super hearing to better understand the unending, undulating shriek,

and it’s within this phantasmagoria that Arno asserts an even harsher reality by stating, “The major general wants you,”

and because that’s preposterous, Bagger pshaws, “You gotta learn your stripes, kid,” but Arno shakes his head and insists, “I know my stripes,” and Bagger peaks an eyebrow and says, “You mean the first lieutenant,” but Arno shakes his head harder, “No, the major general,” and Bagger levels a look, “Major Chester?,” and Arno shakes his head hard enough to untwist the fool thing off, and Bagger asks, now with a cramp of concern, “Brigadier Motta?,” and Arno moans in exasperation, “The major general! The man with the tiny little arm!,”

and descriptions don’t get clearer than that, Bagger’s face goes slack, which causes more mud to slough off, unless it’s really brains this time, and it might be, that’s how hard Bagger’s thinking, he’s done an ace job fleecing privates, corporals, lieutenants, majors, brigadiers, and captains, but no way does a lowly PFC like Cyril Bagger get the chance to interface with the commander of the U.S. 43rd,

and that might mean tales of Bagger’s bamboozles have gone all the way to the top, which could lead to a court-martial, to prison, and to cover his dread, Bagger tries to play it off like nothing, asking, “Yeah? He say why?,” to which Arno shakes his head earnestly, so Bagger just blinks and breathes, blinks and breathes, and sits at the edge of the mass grave, just him, the boy, the fear, and the shriek,

and it brings him close to voicing a fantasy he’s nurtured like a houseplant, in which the two of them, Bagger and Arno, simply stroll the fuck out of this cunting nightmare, Arno sitting atop Bagger’s shoulders like a kid brother, livening Bagger’s path through shell craters and around dead horses, until the terrain goes dreamy, twitching clover patches, handcrafted stone fences, until they find a wee farm more charming than its Iowa equivalents, and acquire it, and live there, the two of them, accruing personal trivia, the only swindle being the years they wasted anywhere else,

and fuck it, it’ll never happen, a fruitcake fantasy to be kept close to his chest, same spot he wanted to pin the ear,

* * *

and so Bagger struggles skyward, and Arno holds out a hand to help, and Bagger clubs it aside same as he does trench vermin, because he’s not the kid’s big brother, he’s just a guy who’s going to get through this war by living how he’s always lived, not giving one shit about anyone, regardless of age or innocence, but he rises too fast, he’s dizzy, he buckles and pitches and weaves and flounders, a necessary struggle, or else he’ll fall into the soupy mass grave he never finished digging but the kill-happy world dug for him, for every last one of them,

III

and as Bagger’s strides are man-sized, Arno has to rabbit his pace to keep at Bagger’s heels, and the kid asks, ignorant as ever of being a pest, “You think Korak’s going to kill Baynes?,” and Bagger replies, “Nah. Baynes is going to chop up Korak and make stew out of him,” which sets off loon laughter from the kid, who goes about listing all the reasons Korak the Killer is too powerful and crafty to be taken down by the silver-spoon likes of Morison Baynes,

and Arno prattles on, “You think Korak is going to rescue Meriem again?,” to which Bagger snipes, “If I hadn’t lost my sewing kit, I’d sew your lips shut,” but the kid’s happy chatter proceeds unbothered, characteristic of their daily palaver, in which the kid asks a thousand dunderhead questions about whatever they’re reading and Bagger doles out the most upsetting answers possible,

and their current book is The Son of Tarzan, published in 1915 by Something Something Burroughs, little boy stuff, but Arno is, in fact, a little boy with a little boy’s passions, and as far back as Camp Winn at Fort Sinclair, the kid was badgering recruits about their dime novels until they started tossing their finished books at the kid, never realizing that just because Lewis Arno liked adventure stories didn’t mean he knew how to read,

and you get one guess which soldier Arno chose to confess his shame of illiteracy, fuck the luck, and before long the kid was begging Bagger to read him The Prisoner of Zenda, and though Bagger initially told the kid to scram, war is a slog even when you’re not warring, and at last came the day Bagger was too pooped to resist the kid’s begging and ripped the book from Arno’s hand and began reading aloud with plans to insert passages of sickening violence and shocking pornography, only to find himself engaged by the plot,

and it’s bar none the biggest mistake Bagger’s made in the Army, and worse still, he keeps making it, King Solomon’s Mines, The Count of Monte Cristo, Treasure Island, and now The Son of Tarzan, a tale in which, so far anyway, Tarzan barely appears, the stage ceded to the ape-man’s civilized son, who follows his daddy’s footsteps to become Korak the Killer, an idiotic coincidence, but diverting enough as Bagger, of course, inserts explicit content, Tarzan revised to be a randy sodomite and Lady Greystoke a nudist cannibal, to which Arno only nods along, suggesting there’s no atrocity Bagger can concoct the Great War hasn’t reduced to believability,

and with Arno still at it, “Big Bwana is really Tarzan, right, Bagger? Bagger, you can tell me!,” they pass a side of human ribs still flexing, powered by the heart, always the last organ to let go, and because there’s no time to direct Arno away from it, Bagger stomps the heart before the kid can notice it, and the heart feels like his own,

and here come several aching somnambulists through the fog, HQ staff dragging wagons so heavy with carnage they need to be yoked through the mud like sleds, arms and legs and scalps and entrails swinging from the sides, so Bagger distracts the kid, yanking him close, shouting, “Mind that hole!,” to which Arno cries, “Whoa! Close one!,” except there is no hole, and Bagger wonders if Arno knows it and they’re both just playing the role the other needs,

and Bagger drops into the shallowest stretch of trench he can find, knees like hamburger, and when Arno crouches like he wants help, Bagger pretends not to notice, he’s not the kid’s daddy, and he walks off and hears Arno splat down in the mud, so what, they’re all muddy, though he wishes it was the kid’s landing that made the trench quiver instead of the war machines over the next slope, either that or a hundred thousand of Ludendorff’s Huns exiting the fortified pillboxes of the Hindenburg Line, a choppy sea of pointed helmets heaving south,

and it could also be the shriek, palpitating everything,

and whatever it is, it’s bothering the Butcher Birds of the 43rd, they low like Iowa cows needing milking, mud slurping at their hooves, and Arno scurries ahead to lead Bagger through a U-shaped elbow, a turn that reveals the remains of Company P, there’s Lieutenant Jules Aquila blurting inspirational falderal and slapping the chests of men dead on their feet, there’s Sergeant Moss DiStefano passing a salt vial beneath the noses of those who need it,

and it’s all because P Company, too, is finally on the move, forming a column to march, which means Bagger needs to fall in, but before he can, Arno swerves left, away from the line of forty-some drooping men and past Father Muensterman, who pukes into his own carefully cupped hands as if he intends to pass off the vomitus as both body and blood,

and they bank into the lopsided amphitheater of a shell crater, a striated bowl of clay scalloped as if from a giant’s closing fist, painted by vertical stripes of blood that rise up the sides of the bowl, a pattern accentuated by a mash of tissue right where a clock should hang, something yuletide about it, the color of fruitcake, the shape a wreath, and only the ornaments of a dozen teeth tell Bagger it used to be a human head,

and the next thing he notices are three men, not dead in the mud but standing in formation with Springfield rifles at their sides and spines at high attention, and though Bagger has but seconds to look, he identifies them as the three most disposable men of Company P, a label that makes him curl his lip with detestation and superiority before he gets to the demoralizing punch line, that it isn’t the three most disposable gathered here but the five,

IV

and with a flare of coat hem, a man in the center of the crater turns, a soupçon of operatic grace in the graceless affront of the gutted countryside, and Bagger jerks back, he didn’t see him there, though the high-laced field boots are unmistakable, and surprising, for one might expect a sideways lean from the man, given the lesser weight of his withered right arm, but no, his martial stance is ramrod, all crookedness resolved by the golden walking stick clawed by the leather-gloved hand,

and it’s Major General Lyon Reis’s costume that’s most often mocked by the Butcher Birds, the shin-length wool trench coat, once ivory, now smoke-stained and unbuckled to affect a cavalier’s flair, three coin-sized medals dangling over his left breast from pentagonal ribbons, typical for his rank but arranged with a space reserved for a medal not yet earned, which, according to rumor, is the Medal of Honor, that’s how certain Reis is that the war will win it for him, how sincerely he believes it’s his due,

and it’s highly irregular for Reis to be speaking to privates without his staff, who must be busy pushing carts through mud, or without the leaders whose ranks fall between Major General Reis and Private Bagger, in this case, in ascending order, Lieutenant Aquila, First Lieutenant Hollis, Major Chester, and Captain Greisz, none of whom like Bagger, and the feeling’s mutual, though now Bagger feels a pipsqueak yearning for those authority figures to protect him from big, bad Major General Reis, whose light brown eyes have gone arachnid with the points of several lanterns,

and Reis asks, “Did little bunny get lost in the warren?,” and Arno, Tarzan fantasies forgotten, replies, “No, sir,” and looks like he’s going to blabber a more detailed excuse, so Bagger knuckles the kid in the back and takes over, saying, “Sorry, sir, we took a pretty direct hit back on burial detail,”

and Reis lifts his lips to his nostrils, a disgusted inhale that siphons the lower half of his face into his sinuses, which broadens the Van Dyke beard the major general inexplicably finds time to manicure, the vanity of youth, some of the boys say, for Reis is the youngest division commander in the Army, though reports of his age hitch higher with every strategic blunder, Reis was thirty-three in Alsace, thirty-five in Vosges, forty on September 26 when the 43rd jumped off at Bois de Malancourt, and now, two weeks into the lathe of the Meuse-Argonne, Lyon Reis is nearabout sixty, seventy-five on a bad day, and this is a very bad day,

and Reis leans his head back, back, back, the way the upper crust always look at cretins who dare intersect their path, which tilts his gold-braided cap so the two stars pinned to the front catch fire in the lantern light, eyes more fiery than Reis’s own,

and he echoes, “Direct hit. You think you know about direct hits?,” a question to which Bagger would say yes, if not for the three men slashing him with their eyes to say, Why won’t you shut up, Bagger, why must you always make it worse?, a complaint true enough to make the fly trapped inside Bagger’s rib cage fling itself against prison bars of bone,

and the fly’s been with Bagger since Camp Winn, where there was a poster tacked to the barracks door, I WANT YOU FOR U.S. ARMY, unsound grammar Bagger would have disparaged if he hadn’t been so struck by the man painted on the poster, a top-hatted, red-bow-tied, billy-bearded Uncle Sam who looked uncannily like his father, Bishop Bagger, drowned to death two years prior when the RMS Lusitania was sunk by a U-boat torpedo,

* * *

and once Bagger swatted away the Tennessee flies, he found this Uncle Sam, too, to be more cadaver than man, skin tight to his skull, pearled with putrescence, the ripe pouches of flesh beneath his eyes ready to burst with maggots, and Bagger thought it boded poorly that the man who most wanted him in the army was already dead, it made Bagger reach for the poster to trash it, comeuppance be damned, and that’s when one of the goddamn Tennessee flies zipped right into his open mouth and down his throat,

and now the fly, also named Uncle Sam, lives in Bagger’s chest, all that’s left of Bagger’s father, and though Bagger’s tried to drown the fly with moonshine, incinerate him with cigarettes, even dope him with opium, Uncle Sam’s a tough little bastard, but at least Bagger has him trapped, and one day the shamefly, as Bagger thinks of him, will die, and with it will go that pestering nip of shame, that filmy wing flutter of guilt, and Bagger’s life will be launched anew,

and Reis’s challenges excite Uncle Sam, which Bagger takes as his own challenge, he’ll show the shamefly that he doesn’t kowtow to imbecilic militance, so he says, “Yes, sir, Major General, sir, direct hits are my area of expertise. If the major general would care to visit, I’d be happy to show him all the pieces. It’s hardly III Corps anymore, sir. More like III Corpse, I’d say,”

* * *

and Reis’s face drops like claybrains and his eyeball arachnoidism spreads until suddenly he’s got too many lower appendages, some legs and a cane, and he’s racing at Bagger like an out-of-control carousel horse, up and down, the leather case of his field glasses pendulating, the Medal of Honor gap gawping like a eyeless socket, and he’s in Bagger’s face, same height yet shouting downward because Bagger is shrinking,

and Reis barks, “I see you find American sacrifice funny, Private Bagger!”

and it can’t be good the major general knows his name, Bagger’s stunned, and it must read on his face as easily as a Tarzan book, for Reis smirks and says, “That’s right, I know you. Shirker. Archschemer. I call you Private Gravedigger,” and he cuts a look at the others, “I have names for all of you. I make it a priority to receive reports on the division’s disreputables,”

and all Bagger can think to do is double down, he shapes himself into a caricature of soldierdom and says, “Major General, sir, I was merely making a lexical observation!,”

and Reis flattens his mustache with an equine blast of hot air and says, with great odium, “You are a mosquito, Private Gravedigger. Imminently squashable. And you will be squashed before this war is over. I won’t do the squashing myself. I wouldn’t give you the honor. Nor do I believe your end will come from one of your ‘direct hits.’ Your demise will be typical to vermin. Your long, greasy tail caught in some trifling mousetrap. And when your tail is thusly pinched, who will come to your aid, Private Gravedigger? These men?,”

and Reis jabs his walking stick at the glowering soldiers, before swinging the stick toward Company P’s column and asking again, “Those men?,” and Bagger knows he’s right, none of these boys give a shit if Bagger lives or dies,

and Reis swears, “You will be solitary in your suffering, Private Gravedigger. No man will risk anything to assist you, as you have risked nothing to assist your fellow man. They might return the favor you gave to their fallen brothers and toss what is left of you down a hole. I should think you deserve your own hole, one of your signature latrines, perhaps, the sort that collapse upon the first stream of piss. Of this resting place, no record will be made, though I do fancy a sign to warn farmers to keep their flocks away. What lies beneath is a man made of poison,”

and with that, Reis sneers, “Wipe the blood of the valiant off your face, Soldier. On you, it is profane,” while Uncle Sam goes amok in Bagger’s chest, the same wingbeat of shame he felt seeing off his father on that final doomed voyage, Bagger wants to punch back now like he did back then, maybe this time literally,

* * *

and he could, Reis is no physical specimen, adenoid eyes, noodle neck, a matronly pelvic misalignment that sets his feet to a 10:10 configuration, shortcomings Bagger presumes originated from whatever defect blighted Reis’s right arm, which all the boys snicker about, one claiming to have seen the little arm employed to brush Reis’s mustache, another swearing Reis keeps a tiny box of tiny cigars to be held by the tiny fingers, but it’s bullshit, no one’s ever seen the arm, it hides inside its specially tailored uniforms and coats,

and even if Bagger saw it, he wouldn’t stoop to ridicule it, the arm’s not the major general’s fault, it’s how he’s twisted his life in reaction to it that has turned his men against him, his refusal to adhere to the frontline rotation the Great War has made standard, his threat to outright shoot deserters, and his belief that flank attacks are unworthy of the 43rd, which forces hundreds of men to directly assault machine-gun nests until they are no longer men at all,

and before Bagger can force Uncle Sam the shamefly down and make a cutting jibe, Very creative, Major General, sir!, Reis’s left arm, the good one, whip-cracks Bagger’s shoulder with the walking stick, and son of a bitch, it fucking hurts, though not as much as a bullet, a fact of which Reis will happily remind him if he produces even a squeak,

* * *

and “Formation!” is Reis’s order, so Bagger stumbles left, blind beneath black plumes of pain, the only sign he’s in position coming from the bump of the next man’s shoulder, and then the crater goes silent, except, of course for the shriek that continues to unfurl in an infinite ribbon, and since Bagger can’t see so good right now, a tableau forms in his mind, the shrieker as a grief-stricken villager watching these five men standing on the gallows, a hooded executioner gripping the lever that, when pulled, will send them swinging till they are dead, dead, dead,

V

and Reis paces the slime in smart spiderleg, indifferent to the day’s necrosis, while just past the vomiting chaplain, the poor devils of Company P force themselves to stay upright on their blisters, awaiting Reis’s order, knees singing, brainpans percussive, eyelids blue flame, radiating loathing for the five flunkies, all of it rancid gravy down Bagger’s throat,

and Reis looks like he could pace like this all day, the far-off booms of enemies and allies as pleasant as garden-party chatter, while magenta clay oozes down the crater like liquified skin, until he says, “It is unlikely any of you have ever been nominated for anything. This, indeed, is how you came to stand before me,” and Reis points his walking stick rather casually at the sky and asks, “What do you see up there? Private Goodspeed,”

and despite Reis and his cane, despite the fresh welt on Bagger’s shoulder, Bagger creeps his eyes left to glance at Private Vincent Goodspeed, a man he knows only by reputation, but who exudes a squirmy, squirrelish air, as thin as birch bark stripped from a tree and topped with a tight bowl of blond hair and the steel-rimmed pince-nez of Woodrow Wilson, so tightly applied the spectacles dig grooves into the sides of his nose,

and what’s most suspicious about Goodspeed is his cleanliness, nobody’s clean out here, even your insides are filthy, you drool mustard gas, sneeze soiled gauze, cry soot, shit mud, but since the start of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, rumors have circulated of a private who goes over the top willingly enough only to stop ten yards out to clean his boots while fellow Butcher Birds meet Jerry’s iron hail, and it has to be Vincent Goodspeed, his olive drabs still olive, the brass buttons of his ammo patch bright as pennies,