Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Peirene Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

New Year's Eve. The last day of the last year of human existence. A high-ranking minister criss-crosses the city with blood on his hands, a dying necrophile attempts to go clean before God, and a traumatized nurse is pressured into keeping a powerful secret. With undisguised glee, a nameless narrator unravels these twisted tales of moral turmoil, all of which are brought to an abrupt close by a cataclysmic collision of time and space. What will remain on New Year's Day? An exhilarating, provocative carnival of a novel, from one of Europe's most distinctive literary voices.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 147

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

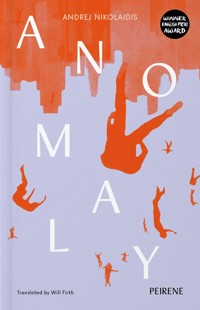

ANOMALY

Andrej Nikolaidis

Translated from the Montenegrin by Will Firth

PEIRENE

ANOMALY

Contents

PART ONE

TOCCATA

then time returns to the shell.

In the mirror it’s Sunday, in dream there is room for sleeping, our mouths speak the truth.

Paul Celan, ‘Corona’10

1

That Was Not God

The lazy eye of the camera follows the blood creeping through the maze. The crimson stream moves indifferently. Since when is bloodshed any cause for concern? What have we done in this world other than wound and distress? The sight of red flowing along the grouting between ceramic tiles is only slightly unusual, mundanely unusual – like a small, inconsequential change in the routine of a once-in-love couple, who walk along a sandy beach near, say, Ravenna, perhaps, and unknowingly count down the last days. That’s how it is: when change comes, the end is nigh. The call for change is the hope of euthanasia, the screenwriter has penned in the margin.

The camera then reveals a crow (an allusion to Auden, we think). It’s ready to swoop down from the windowsill at the young woman lying naked and injured on the bathroom floor. Her 12immobility implies not peace but agony. One of her eyes is open – zooming in on it will reveal the whole horror she’s faced; terror that surpasses the ultimate horizon of anthropological pessimism, a dread comparable only with that of a newborn when it’s torn from its mother and into the world, the screenwriter notes at the bottom of the page.

He suggests to the director that it’s time to acquaint viewers with the Minister. This middle-aged man, well groomed and in an expensive suit, sits on the toilet lid and follows the path of the blood pouring from the young woman’s skull with the attentiveness of parents observing their children in the playground, hovering like a swarm of helicopters over the scene of an accident. The screenwriter notes: THE MINISTER watches the scene of the crime with the attentiveness of an author looking for the possibility of correcting the image they’ve just created; the hope that they’ve reached perfection doesn’t overpower their determination to detect shortcomings.

But the hope of correction will not last. There’s no possibility of return, just as there’s none of erasing the disaster, of returning the hand of fate to the position it was in before it delivered the fatal blow. Stasis is nothing but an illusion, which at the same time simulates the sublime. The Minister’s time is expensive, while blood, as always, is cheap. He looks at his watch, opens the door to leave the flat, turns back – all this if we dare to assume the competencies of the screenwriter, in slow motion, which will emphasize the transition from contemplation to action; the point at which any remorse the 13Minister may have felt is aborted and cruelty is resurrected – and looks at his security guy.

MINISTER

Is she still breathing?

AGENT

Yes.

MINISTER

Put that bag over her head.

AGENT

Where should we take her?

MINISTER

The same place.

AGENT

Why not somewhere new? The lake, perhaps?

MINISTER

The same place.

The camera follows the Minister as he descends a dark staircase; his descent into the world, the screenwriter emphasizes. 14These notes reveal no clues as to the writer’s origin. Who is he? We know he’s read Auden: that’s no small thing. But where is he from? He might have been born into the middle class: university-educated parents, a good school, and then scraping and saving his way through his studies. Yes, he could be middle class: that vigilante militia, whose values, ethics and civil decency maintain the stability of the system, who give their lives to fill the buffer zone that prevents the rich and the impoverished from clashing; lives from which disappointment hasn’t squeezed all hope, lives spent refusing to learn from experience. Yes, he could be one of those whose primary reaction is to maintain the status quo, who doesn’t like change – except the kind they yearn for: the change that will make them rich. He could be a child of those who spent their lives in the sorry belief that if their children studied hard, worked hard and graduated from good schools they’d cross over into the upper class and wave goodbye to their family tree, which is too much like a list of servants and chores in the hands of a butler running a lord’s country house. By maintaining the status quo, the middle class has never seen its progeny move into penthouses in the capital, but it has allowed the owners of the penthouses to further enrich themselves at their expense, and of those at the bottom. Nor will he, an obedient child, live to see that mobility – the delusion of his parents.

It could be like that. Or perhaps he was born rich, in security and tedium that he combats in vain with a pose of solidarity and empathy – feelings he inserts into his texts – and 15his writing is sometimes interrupted by the maid who brings him Ethiopian coffee and shortbread.

‘Descent’ is the writer’s way of telling us that his hero is above the world and its laws. Down on the street, a limousine is waiting for the Minister. Its engine is running.

DRIVER

Where to, boss?

MINISTER

Wherever you want.

DRIVER

Home?

MINISTER

No. Drive.

DRIVER

Did everything go well, boss?

MINISTER

All good. Just drive.

The screenwriter emphasizes to the director the importance of this sequence, where the camera follows the Minister’s seemingly aimless drive through the city. The director 16implements this convincingly, but the scene goes beyond the limits of decency. We can assume that the instruction ‘See Scorsese/Schrader, Bringing Out the Dead’ will make him curse.

The text reads as follows: ‘The limousine turns right.’

DRIVER

Boss, he says the owner of the fast-food place saw them take out the body.

MINISTER

Have them pay him a visit.

DRIVER

OK.

MINISTER

Have them give him five thousand.

DRIVER

OK.

MINISTER

Have them tell him his lease has been paid for the next three years.

DRIVER

OK. 17

MINISTER

He has children, I suppose?

DRIVER

Two daughters: Maša and Lana.

MINISTER

Have them give him an extra two hundred before they leave. As a farewell. They should tell him it’s for presents Have them emphasize: for Maša and Lana.

DRIVER

OK.

The screenwriter then insists on the ‘silence and alienation’ that accompany the Minister as they cruise around the city he rules. It’s obvious that the screenwriter intends to humanize the man who committed a terrible crime in cold blood. This seems superfluous to us, above all because we don’t question the human nature of criminals – they’re criminals precisely because they’re human – and because we see silence and alienation as good reasons why a person would want the power the Minister has. Then his phone rings.

MINISTER

Well? 18

VOICE

He wants to know if it’s done?

MINISTER

Did he pay?

VOICE

No.

MINISTER

Then he hasn’t done his part of the deal.

VOICE

Where should he? The usual?

MINISTER

Zurich.

VOICE

What should I tell him? When will that be?

MINISTER

Next session.

VOICE OK.

Happy New Year, boss. 19

MINISTER

All the best. Say hello to Lucija.

What happens next in a text in which it seems nothing happens – one full of intimations, where what is left unsaid is more important than what is said? The Minister watches the driver in silence. He’s fidgeting in his seat and has dug his nails into the steering wheel.

MINISTER

How’s Sonja?

DRIVER

Not even morphine helps any more.

MINISTER

Drive to the shopping centre.

DRIVER

Yes, boss.

MINISTER

Go in the underground car park. Take money from the suitcase. Go and buy Sonja a necklace – the most beautiful you can find. I’ll wait for you in the car. 20

DRIVER

Thanks, boss. But she doesn’t need anything any more.

MINISTER

It’ll be good for your daughter. It’ll be good for Sonja too. She’ll die more easily knowing she’s leaving something valuable to her child.

The Minister then visits his mother. The red traffic light is flashing.

MINISTER

Take me to see the old girl.

The writer spares no effort in describing the old woman’s home. We’re inclined to think he’s writing about a house he knows well. We’re tempted to succumb to the weakness of the ignorant reader, to treat the artistic text as a tabloid confession and ask ourselves: what is the author telling us about themself? Or is it the author who’s leading us to such an obviously flawed, unworthy reading? In any case, we resist. ‘She didn’t hear him come in,’ we read.

Mother and son are sitting at the table. She’s anxious. He’s calm, with the demeanour of a knight safe inside his armour, which no toy sword brandished by the so-called public in their childish games can penetrate. 21

MINISTER

How’s my queen?

MOTHER

Like a dying beggar.

MINISTER

An old queen is still a queen. I’ve brought you cake.

MOTHER

A dead queen is dead.

MINISTER

Don’t be like that. You’ve got a long time to go.

MOTHER

Not so long as to see you fall, I hope.

MINISTER

I won’t fall.

MOTHER

Everyone falls. Everything will fall.

When he leaves, his mother doesn’t want to hug him. But she accepts a kiss. The next frame shows the Minister getting out of the limousine. 22

DRIVER

Should I come tomorrow?

MINISTER

The day after. Spend some time with your family.

This scene, as we will soon see, is an introduction to the screenwriter’s sarcastic praise of traditional values. The Minister’s return to the warmth of his family home is the culmination of his re-humanization: he, whom we perceive as a sociopath at the beginning, is presented as a husband and father – one of us. As he takes off his coat, two children rush towards him.

MINA

Daaaddy!

MINISTER

Gimme a squeeze… Have you opened your presents?

IVAN

How did you know I wanted a radio-controlled car?

MINISTER

How often have I told you: Dad knows everything. And you, cutie? 23

MINA

I took a photo of her and sent it to Milica.

MINISTER

And what does she say?

MINA

She’s always wanted one like this too.

MINISTER

You know what? She’ll get one tomorrow.

MINA

Daaaddy!

Good cheer prevails at the dinner table. It would be pointless to look for any sign of concern or remorse on the Minister’s face, the author writes in the margins of his text. It’s pleasant and comforting to see a man in such complete peace with his own misdeeds – it instils hope that we’ll be able to forgive ourselves everything. And we will: without a doubt, we will. The human race owes its history, as well as its future, to the fact that we’ve always been able to turn our backsides to the graves of those we maltreated, and then seek absolution. The idea of forgiveness is wedged like a backbone in our culture and guarantees that things will stay the way they are. Forgiveness for oneself, of course. Forgiveness for others figures here merely as a pretext, an investment. And all our virtue – forgiveness, 24forgiveness! – as a spectacularly deceptive prelude to giving up virtue.

‘The roast turkey was perfect,’ we learn further.

MINISTER

Are you tired, dear?

WIFE

I am, to tell the truth. Though Magdalena did all the cooking. You?

MINISTER

Not at all. Did you give Magdalena her presents?

WIFE

For goodness’ sake, darling…

MINISTER

Don’t mind me. You know I worry too much. Worry is a sign of love. Isn’t that right? But… she really is an angel. Sometimes I think: what would we do without her?

WIFE

Get ourselves another housekeeper.

MINISTER

Of course… but she wouldn’t be Magdalena. We don’t want another housekeeper, do we? 25

WIFE

No, darling. If you say so, we definitely don’t.

Husband and wife head off to bed. She listens to his breathing.

WIFE

Are you asleep?

MINISTER

No.

WIFE

You’ll never forget you have children?

MINISTER

You know I won’t.

WIFE

You’d never let your children grow up in shame?

MINISTER

You know I wouldn’t.

WIFE

There was blood on your shirt. 26

MINISTER

Did you wash it?

WIFE

I burned it.

The author is hinting, for the first time, at the restlessness that engulfs the Minister. Even if they had slept, we learn, their calm wouldn’t have lasted. There’s no peace any more, not even for the righteous. The earth shakes, and a deafening noise comes from the sky. It’s the sound of the world splitting, falling apart. A crack opens in the ceiling and glares at the Minister with a dark eye. He runs to his children’s room and leads them out into the hall, where their mother is waiting for them. The Minister hugs all three of them. ‘God will never forgive,’ he thinks. He kisses his daughter on the head and says: ‘God, how I love you all.’

Immediately below this, in his untidy, barely legible hand, resembling a cardiogram, the screenwriter has noted: Yes: love redeems. God loves, God has a weakness for love. But…

That was not God.

*

We were sitting in an outdoor cafe by the sea, finishing the script that had been entrusted to us. We rated it positively. Our assessment was: this short film deserves public funding. 27

Our satisfaction at an easily earned fee for a hardened script editor was interrupted, to our immense regret, by the commotion of the other customers. The considerable energy we wasted trying to ignore them could have been better spent on something else; anything else. They hampered our reading with their stupid comments, with the forceful words they could hardly articulate – barely any better than cows or horses if they tried to speak – and they arranged those deformed words into hideous sentences that followed the rules of syntax only a little more consistently than mooing or bleating. In any case, they’d noticed something unusual in the sea; a sight had appeared before them that tore them from their chairs and made them walk off towards the beach as if enchanted.

A flotilla of small vessels had emerged from the water. Tattered Serbian flags hung limp and dripping from rotting, shell-encrusted masts, and beneath them stood a motley bunch of First World War infantrymen, ragged and worn from a long march, with rusty rifles. They were visibly disoriented: not only

did we have no idea what they were doing in the sea, so far off the coast of Corfu, but they themselves had no notion why they’d been in that watery grave.

Humanity itself – including those men, who, from all we know and see, should have been dead for over a century – is doomed to general disgust and astonishment, we thought as we watched. Life itself is a scandal that the existing world struggles to tolerate. We celebrate birth, mourn death and condemn suicide: life is good, death is bad. But to live means to be a hypocrite: sooner or later you’ll come to see others as a 28nuisance, whose very existence mistreats you, and you’ll conclude that it would be best if they didn’t exist at all.

Then comes the time for malicious glee. After all, it isn’t a luxury but a defence mechanism. It’s not a matter of style but of survival. A person filled with malicious glee isn’t protected; far from it. But neither do they stand naked before a world they’re not sure even exists. In any case, their bad intention is unquestionable. Maybe it’s something, maybe it’s nothing. Why it occurs, or doesn’t, isn’t clear either. But it is hateful; oh yes. And yet, that afternoon, there was no time for malicious glee. Because…

People started raining down on the city out of the atmosphere, like a shower of meteors. The scene was obviously a reversal of the Ascension. Instead of the chosen ones whom God would raise to heaven, it was the doomed who came hurtling from the sky, on fire, like falling stars.

Human bodies crashed into the ground and burst like water balloons that children like to pelt each other with at the parties parents organize because their child is one year closer to death. When Mother Earth drew them to its bosom, the blood of the fallen splashed far and wide. Some of them landed on passers-by, thus ending their lives in the most bizarre way; some came down on top of parked cars; others ended up on the rocks, from which the sea would wash away their blood.

We looked at the canopy above us. It was robust enough to hold back the rain, but not meteor people. We decided it was best to withdraw to the safe interior of the cafe, even though the other patrons were screaming in the shrillest panic, which wasn’t exactly conducive to a peaceful afternoon coffee. 29

Then we noticed it was snowing. The snow wafted down leisurely, as if nature was expressing its indifference to the heavens dumping a load of people. We had to give nature credit, at least this once; the sight of human bodies plummeting to earth in flames was only slightly unusual – far less unusual than an act of human sincerity and kindness, if we can conceive of such a thing at all.