Apocalypse of Love E-Book

54,87 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

An Apocalypse of Love is a collection of essays on the many facets of Cyril O'Regan's work to date written by both prominent and rising scholars in the fields of philosophy and theology. Essay topics included in this volume range over his entire corpus, including appreciatively critical analyses of his early and current work on Hegel, rhetorical and pedagogical styles, spiritual theology, engagement with Hegel and Heidegger, von Balthasar and John of the Cross, kenosis, Eric Voegelin, his relation to post-moderns such as Lacan and Bataille, and poetry both published and unpublished.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Praise forAN APOCALYPSE OF LOVE

“Cyril O’Regan has explored in immense detail and with an abundance of new insights Voegelin’s question of the gnostic dimension in modernity, and Balthasar’s question of Christian theology’s relationship to its problematic margins of gnosticism, apocalyptic, neoplatonism, pantheism and esotericism. The bulk of his scholarly contribution can sometimes hide its equally substantive theological significance for the future. The great merit of the fine essays in the current volume is that they bring this significance more fully into view.”

—John Milbank, Emeritus Professor, University of Nottingham

“This is a superior collection of essays, amounting to a kind of Platonic form of the Festschrift. It is in the genre of the Festchrift to range from the scholarly to the personal. This volume runs from awe-inspiring scholarly pieces, like Marion’s chapter about Kenosis and Astell’s essay on O’Regan’s poetry, to invaluable personal reminiscences (Cunningham), chapters of spirituality (Nussberger and Cavadini), and chapters about the frequent targets of O’Regan’s pen, such as Hegel (Walsh). This volume of essays walks and talks like a Festchrift, but many of the contributors go so far beyond the regular brief for such volumes that they establish a kind of dazzling, superior norm for the genre.”

—Francesca Murphy, University of Notre Dame

“Apocalypse of Love is a fitting title for this collection of essays that pay homage to the breadth and depth of Cyril O’Regan’s vast work. The essays here are superb, offering glimpses into his intellectual development during his days at University College Dublin, reflections on St. Joseph, after whom he was named, and rich insights into his work on aesthetics, Thomas, Kant, Hegel, Russian Orthodox thinkers, Balthasar, and much more. Put together by students, colleagues, and friendly critics, these essays are, like O’Regan’s work, well worth reading. They take us ever deeper into one of the most astute guides of philosophy, theology, and literature in the modern era. We are in their and his debt for such a beautiful journey.”

—D. Stephen Long, Cary M. Maguire University Professor of Ethics, Southern Methodist University

“Cyril O’Regan’s work represents one of the jewels of contemporary philosophy and theology. The range and depth of his thinking are extraordinary. The insights are at times stunning; you leave a lecture with your mind on fire; or you read a passage and step away to get your bearings. He has a way of changing the whole intellectual landscape in a brilliant turn of phrase or in the twinkling of his eye. His rhetorical skill can be overwhelming; he did not kiss the Blarney Stone back in Ireland; he swallowed it. It is a joy to welcome the celebration of his achievements to date. It is an added bonus to have a superb introduction and overview of his work.”

—William J. Abraham, Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas Texas

“This exceptionally probing and appreciative collection of essays offers a multi-faceted assessment of Cyril O’Regan’s contributions to contemporary theology. Throughout the volume a portrait emerges of O’Regan’s academic theology as “superbly attuned” to Hegel, Newman, Heidegger, and Balthasar, and more broadly to the ethoi of both modernity and post-modernity. The collection also draws out implicit features of O’Regan’s own theology and brings them into the open, raising the reception of his considerable corpus to a new level of clarity, sophistication, and promise. The book additionally presents an enriching engagement with O’Regan’s poetry, augmenting the reader’s understanding of his inter-disciplinary approach to contemporary theology. Last, the volume offers reflections on O’Regan as a teacher, mentor, and friend, and in these pages the reader beholds an image of Cyril O’Regan as “delighting in the truth” (Augustine), practicing a theology of “ecstatic surrender,” and as exceedingly generous in his engagement with the thought of both his intellectual allies and opponents.”

—Mark McInroy, Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology, University of Saint Thomas, Saint Paul, MN

“An Apocalypse of Love offers readers a golden chain of commentaries whose unity is found in the relationship of each idea to the others rather than in a single thesis. The book contains thoughtful contributions that at once summarize and interpret Cyril O’Regan’s wide-ranging work, doing so in such a way that we are left desiring to re-read O’Regan and yet also to move past him to the winding pathways he has spent his career urging us to explore. From poetry to Hegel to the deep mysteries of the cross, Apocalypse asks us to consider the glories and devastations of a life given over to genuine wonder at God’s work and the modern world.”

—Anne Carpenter, Assistant Professor of Catholic Theology, Saint Mary’s College of California

“Martin and Sciglitano have assembled a fitting tribute to the achievements of an exceptional theologian. The essays in this volume—by an outstanding group of scholars—cover themes as profound and wide-ranging as O’Regan’s own contributions. More impressively, they pay homage to O’Regan’s work by drawing it into dialogue with constructive proposals at the intersections of theology, philosophy, and literature. Readers will find here an indispensable resource for engaging a truly indispensable conversation partner.”

—Patrick Gardner, Assistant Professor of Catholic Studies, Christopher Newport University

The Crossroad Publishing Company

www.CrossroadPublishing.com

© 2018 by Anthony C. Sciglitano, Jr. & Jennifer Newsome Martin

Crossroad, Herder & Herder, and the crossed C logo/colophon are registered trademarks of The Crossroad Publishing Company.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be copied, scanned, reproduced in any way, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of The Crossroad Publishing Company. For permission please write to [email protected]

In continuation of our 200-year tradition of independent publishing, The Crossroad Publishing Company proudly offers a variety of books with strong, original voices and diverse perspectives. The viewpoints expressed in our books are not necessarily those of The Crossroad Publishing Company, any of its imprints or of its employees, executives, owners. Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time, the author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, dam- age, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. No claims are made or responsibility assumed for any health or other benefits.

Cover and text design by Sophie Appel

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8245-9919-5

Books published by The Crossroad Publishing Company may be purchased at special quantity discount rates for classes and institutional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected].

To Cyril O’Regan,

lo più che padre

“Therefore, I pray you, gentle father dear,

to teach me what love is: you have reduced

to love both each good and its opposite.”

He said: “Direct your intellect’s sharp eyes

toward me, and let the error of the blind

who’d serve as guides be evident to you.

The soul, which is created to love,

responds to everything that pleases, just

as soon as beauty wakens it to act.

Your apprehension draws an image from

a real object and expands upon

that object until soul has turned toward it;

and if, so turned, the soul tends steadfastly,

then that propensity is love—it’s nature

that joins the soul in you, anew, through beauty.”

—Dante, Purgatorio XVIII, lines 13–27

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Foreword: A Personal Reflection

Lawrence S. Cunningham

Introduction

Jennifer Newsome Martin

CHAPTER 1. The Mystery of St. Joseph in the Memory of the Church: A Father Rich in Mercy

John C. Cavadini

CHAPTER 2. Kenosis, Starting from the Trinity

Jean-Luc Marion | Translated by Tarek R. Dika

CHAPTER 3. Balthasar’s Theology of Christ’s Impasse and “Dark Night”

Danielle Nussberger

CHAPTER 4. Theology in the Middle Voice: Thomas Aquinas and Immanuel Kant on Natural Ends

Corey L. Barnes

CHAPTER 5. Haunted by Heteronomy: Cyril O’Regan, Hegelian Misremembering, and the Counterfeit Doubles of God

William Desmond

CHAPTER 6. On Hegel: Sorcerers and Apprentices

David Walsh

CHAPTER 7. Christian Theology after Heidegger

Andrew Prevot

CHAPTER 8. Delighting in the Truth: St. Augustine and Theological Pedagogy Today

Todd Walatka

CHAPTER 9. Philosophical and Theological Historiography in The Red Wheel

Brendan Purcell

CHAPTER 10. O’Regan as Origen in Alexandria

Ann W. Astell

CHAPTER 11. “As love, the giver is perfect”: Love at the Limit in the Thought of Cyril O’Regan

Jay Martin

CHAPTER 12. The Unity of Cyril O’Regan’s Work: Narrative Grammar and the Space for a Post-Modern Theology

Anthony C. Sciglitano, Jr.

Poetic Epilogue

Cyril O’Regan

“On the Nile”

“Waiting for the Barbarians I”

“Requiem for Marguerite (d. 1310)”

Contributor Biographies

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful acknowledgments are owed to the many contributors who eagerly took to this task and helped to honor Cyril, his work, and his friendship in such a substantive and rich manner. In particular, Geraldine Meehan provided uncommonly sympathetic and pragmatic insight for this volume, knowing better than we where to look for contributors and pointing the way in a perfectly clandestine manner. We are also thankful to the early readers of the full manuscript who agreed generously to provide endorsements for our volume, including William Abraham, Anne Carpenter, Patrick Gardner, D. Stephen Long, Mark McInroy, John Milbank, and Francesca Murphy.

Gwendolyn Herder graciously took on this project at Crossroad Publishing Company, where Chris Myers has been an excellent guide and steward of our progress. His is a gentle and helpful hand. We want to thank also the superb team at the press of editors, designers, and those in marketing as well.

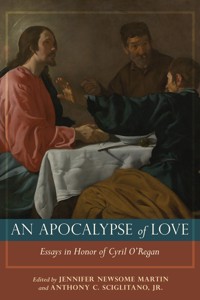

In keeping with its new Open Access policy, the Metropolitan Museum of Art supplied free of charge the beautiful cover image, the oil painting “The Supper at Emmaus” by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1622–23), which depicts the moment of recognition at which the disciples knew Jesus for who he truly is (Luke 24:13–35). The Met appears to believe that art ought to be shared rather than hoarded; we are immensely appreciative for their generosity.

We are exceptionally grateful for the generous support of the University of Notre Dame’s Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts (ISLA), the McGrath Institute for Church Life, the Department of Theology, and Professor Lawrence Cunningham in particular, whose financial contributions have made the publication of this volume possible.

JNM: I am indebted to my co-editor Tony Sciglitano, whose fantastic sense of humor, aesthetic sensibilities, and especially good taste in whiskey has made light the burdensome and pleasant the tedious. I am also grateful to my enormously supportive colleagues in the Program of Liberal Studies at the University of Notre Dame, particularly for the consistent and compassionate friendship of Andrew Radde-Gallwitz. And though the entire project is in a sense an expression of gratitude for the formative influence of Cyril O’Regan both personally and academically, I offer an explicit thematization of it here. Finally, to my husband and always first reader Jay Martin, I owe the greatest debt for the performance of his own decades-long “apocalypse” of love. Polish poet Czesław Miłosz famously said that “one can believe in God out of gratitude for all the gifts”; such a proposal is manifestly easy to accept in the face of the giftedness all around me.

ACS: It has been a privilege to work on this volume with Jennifer Newsome Martin. Her steady and efficient editorial hand, her keen eye for detail and insistence on excellence have elevated this volume. It helps that she is a pleasure to work with (or, with which to work). I am also grateful for the bourbon that catalyzed this collaboration. I want to thank my family who have always been supportive of my academic life and without whom it would have been impossible. In particular, I want to thank my cousin, Brian Sorrentino, who many years ago gave me my first Hegel book, Miller’s translation of the Phenomenology of Spirit, and thus made possible the impossible. And, of course, my gratitude goes to my wife, Julie, whose love suggests the impossible of another plane every day.

FOREWORD

A Personal Reflection

LAWRENCE S. CUNNINGHAM

FOR WELL OVER A decade, Cyril and I had adjoining offices in Malloy Hall on the campus of the University of Notre Dame, and rare was the day when he was not at my door or I at his. I would jokingly refer to our quotidian visits as my chance for spiritual direction. One of my few sorrows since my retirement is not having the pleasure (“pleasure” is the mot juste) of his daily company. Professionally, we served as colleagues in the department and labored together on any number of academic committees, and it was always a signal honor to be asked by him to be a reader of dissertations for many of his numerous Ph.D. students. I would always tell those students that they needed to appreciate how blessed they were to have a professor who would spend so much time with them and help make them better writers, but—and this is most important—teach them to resist any temptation to indulge in cant, padding, or sloppy thought. On such pages this most pacific of men would yield the red pen with militancy. However, unlike some self-regarding academics, he never performed this correction with a view to humiliating a student.

While I have given up my Malloy office, Cyril and I still see each other on a regular basis. Our favorite rendezvous is a Friday lunch at a local Indian restaurant where we spend an hour or so engaged in academic gossip (of which he is facile princeps), catching up on current work, commenting on sports (in which he takes a keen interest), and taking the pulse of the department in particular and the university in general. Most of lunch is punctuated by not-too-raucous laughter when Cyril can let loose with that sly wit and baroque language for which he is justly famous. I have seen many faculty members imitated by their graduate students, but Cyril is hard “to do,” since most students do not have the vocabulary to pull it off, and they most certainly do not have the command of that wicked patois of his native Ireland.

Cyril and his wife Geraldine Meehan are unabashedly companionable, and that company decidedly includes their well-loved son Niall (my wife is Niall’s Confirmation sponsor) and the family dog, Matilda, to whom I have added the name “Prancer” for her vigorous gait when (usually) Cyril takes her on walks. Walking Matilda is not much of a chore for Cyril, since I have observed over the years that—like many a person who came late to driving—he is a determined walker who seems to prefer that mode of conveyance on his daily trips to and from campus. I have it from reliable sources that when he taught at Saint John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, he regularly walked from his home in St. Joseph across the highway to the campus of Saint John’s, even in those notoriously cold Minnesota winters.

Here is something about Cyril that rather astonishes me: he never seems to be in a hurry. For someone who is a prodigious scholar, a fully engaged teacher, a generous giver of time for all sorts of academic committees, and a committed family person, he appears to go through life seemingly never harried. I am equally astonished that he does not wear a watch or keep an appointment book; if he possesses a cell phone, it is one of the better-kept secrets in the Western world. Still and all, he is always on time for meetings, classes, and writing deadlines and makes those deadlines while never seeming to be in a rush. How he manages this placid way of proceeding I mark down to his intelligence.

When he writes—and he does so prodigiously—he writes fully. I have often teased him by saying that my essays are about as long as the book reviews he writes. When he speaks informally at campus “talks,” he does so from fully written texts that are as much a joy to read as they are to hear. What many do not know is that Cyril is also a regular writer of poetry. He has on occasion shown me completed poems that are wonderfully crafted but austere in a fashion that his prose is not. Why he has not published more of his poetry is a mystery to me; if he has published it, it is his secret. Does he have a nom de plume?

Of course, it is Cyril’s scholarly writing that has made his reputation. His first major publication, The Heterodox Hegel (1994), was a revision of a dissertation written under the direction of Louis Dupré at Yale with the subtitle “Trinitarian Ontotheology and Gnostic Narrative.” The subtitle hints at the subsequent direction of his research with the publication of the two books Gnostic Return to Modernity (2001) and Gnostic Apocalypse: Jacob Boehme’s Haunted Narrative (2002), while he has in production two more books mining the Gnostic theme under the tentative titles German Idealism and Its Gnostic Limit and Deranging Narrative: Romanticism and Its Gnostic Limit. In a similar vein, his Père Marquette lecture has been published under the title Theology and the Spaces of Apocalyptic (2009).

The above-cited works create a perfect background for his interest in and expert commentary on the magisterial theological corpus of the late Hans Urs von Balthasar. He has written much and directed some wonderful dissertations on the thought of the famed Swiss theologian. He took a vacation from his writing on Gnosticism to investigate the intellectual matrix out of which Balthasar’s theology arose, which resulted in a two-volume work under the generic title Anatomy of Misremembering. The first volume, on Balthasar’s response to philosophical modernity, with special emphasis on Hegel, is already published (2014), and the second volume, on metaphysics and the prospects of theology, with a focus on Heidegger, is in press as of this writing.

To take on a serious study of Balthasar is to wrestle with the life work of a man whom the late Henri de Lubac called the most learned man in Europe.1 To understand Balthasar fully is to commit oneself to a generous understanding of the Christian past, ranging from the Fathers East and West as well as the grand medieval tradition and that of the early modern. Hence, it comes as no surprise that Cyril has written rich essays on Balthasar in relation to Newman, Eckhart, and Augustine, to mention just a few. That sweeping knowledge of the past has allowed Cyril to construct Notre Dame courses that take into account these traditional figures, and to make forays into the world of contemporary theology, philosophy, and literature. With all due deference to the late Isaiah Berlin, Cyril is one of those thinkers who exemplifies both the hedgehog and the fox.2 He escapes those tired categories of “liberal” and “conservative,” and it would be otiose to try to pigeonhole him as such. His intellectual interests are too capacious and too wide for such lazy labels. He is “catholic” to the bone in the etymological meaning of the word.

Elsewhere in this volume old friends, former students, and present colleagues will memorialize Cyril’s scholarship with a set of celebratory essays to honor his sixty-fifth birthday. Such an occasion, despite the fact that the social security checks may commence, only marks mature middle age, so it is with hope that we look forward to decades of further work coming from his learned pen. There are academics who retire at sixty-five, but they tend to be those who, in reality, retired long ago and are, if truth be told, only retiring their yellowed lecture notes. Those who have a genuine inquiring intelligent mind, like that of our honoree, will say what Thomas Merton said at the end of his classic The Seven Storey Mountain: “Finis libri sed non quaerendi”—the book ends here but not the search.

I have known Cyril since he came to Notre Dame and count him among my best friends. Of him I can only repeat what that old wisdom writer, Jesus, Son of Sirach, said: “Faithful friends are a sturdy shelter/whoever finds one finds a treasure. Faithful friends are lifesaving medicine” (Sirach 6:14, 16).

1 Henri de Lubac, “A Witness of Christ in the Church: Hans Urs von Balthasar,” Hans Urs von Balthasar: His Life and Work, ed. David L. Schindler (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991), 272.

2 Isaiah Berlin, The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History, ed. Henry Hardy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013).

INTRODUCTION

JENNIFER NEWSOME MARTIN

AN APOCALYPSE OF LOVE: Essays in Honor of Cyril O’Regan is a celebratory collection of critical essays by contemporary theologians and philosophers in honor of Cyril Joseph O’Regan (b. 1952), Huisking Professor of Theology at the University of Notre Dame and author of the magisterial two-volume The Anatomy of Misremembering: Von Balthasar’s Response to Philosophical Modernity, Volume I: Hegel (The Crossroad Publishing Company, 2014) and Volume II: Heidegger (The Crossroad Publishing Company, forthcoming). Given its genre as an homage, this volume comprises a tribute to and a celebration of the ongoing legacy of a notable modern theologian. Far beyond this function, however, it is also a constructive investigation of the state of contemporary theological scholarship in response to O’Regan’s interventions, which help to set the terms for what it might mean to do pioneering work in systematic theology, especially that which is philosophically and literarily inflected.

Certainly, the voluminous contributions of Cyril O’Regan to contemporary theology cannot be subsumed under one simple category or heading. His academic range of expertise is frankly astonishing—John Henry Newman is treated alongside Valentinus, Jacob Böhme, moderns and post-moderns, Irish literature, experimental poetry, Gnosticism, Hans Urs von Balthasar, William Blake, Hegel, Heidegger, Schelling, Meister Eckhart, and Hölderlin, not to mention patristic and medieval authors. We requested from our contributors substantive, intellectually hefty essays that would not only honor Cyril’s immense contributions to date, but also publicize and make more accessible the fullest possible range of his work. That includes not only the philosophically and theologically thick kinds of contributions such as The Heterodox Hegel, the Gnostic Return in Modernity series, and the two volumes of The Anatomy of Misremembering, but also—no less carefully prepared and intelligently wrought—the kinds of things he has written for the popularly pitched “Saturdays with the Saints” series before Notre Dame home football games, in the sheaves of his largely unpublished poetry, lecture notes for his graduate and undergraduate courses, and in the marginalia of the thousands upon thousands of draft pages of the (prodigious) number of theses and dissertations he has directed or co-directed over the years. His contributions to the field of contemporary theology are thus not only academic, but also pastoral, pedagogical, and personal. What is doubly extraordinary about O’Regan’s original contribution to the theological project alongside its massive scope is that even in its diverse applications, both the range of work and the man himself present as a composition, with a recognizable tonality, timbre, and rhythm that resonates not only through his whole body of theological and philosophical scholarship, but also in the character of his personal, professional, and spiritual life.

These essays, which are generally irenic but not uncritical, certainly do not strive to be exhaustive in scope, but they are comprehensive at least in their efforts to address elements of the full range of O’Regan’s interdisciplinary corpus. When taken collectively, the essays presented herein demonstrate and even perform the lithe and dynamic movement between genres that mark his theological, philosophical, and literary contributions. The reader may approach this text, then, as a kind of silva rerum, a “forest of things” that simultaneously allows for multiple and distinct perspectives, but one that is also correlated thematically; like Kristina Sabaliauskaitė’s novel that bears the same name, the “family” of our contributors is likewise multi-generational. That is, this book creates a democratic space both for established and emerging theologians and philosophers to catalogue, assess, exemplify, extend, or supplement O’Regan’s wide-ranging contributions in and on their own terms and according to each of the respective contributor’s area of expertise, whether they be in the early, mid, or later stages of their academic careers. Essays include appreciatively critical analyses of Cyril’s work on and engagement with Hegel, hermeneutics, historical theology, rhetorical and pedagogical styles, spiritual theology, Heidegger, love, mysticism, kenosis, Eric Voegelin, psychoanalysis, post-modernity, poetry—both published and unpublished—and a handful of more personal reflections. With respect to the last, we are especially pleased to have a personal appreciation offered by Lawrence S. Cunningham, Cyril’s long-time office mate, colleague, and friend, as the foreword to the entire volume.

In “The Mystery of St. Joseph in the Memory of the Church: A Father Rich in Mercy,” John Cavadini considers the central though utterly anonymous position of St. Joseph in the Church’s living memory. His essay locates the phenomenon of friendship in this space of mystery—whether it be friendship with another person, the saints, with Christ, or in the Church—offering a richly theological meditation that mines the tradition (chiefly the Protevangelium of James and homilies from Origen) not only on the identity of Joseph as such, but on the ordinary mysteries of fatherhood, sonship, and marriage. Central to his discussion are kenotic themes of erasure and renunciation: of the hidden signifier of Joseph’s paternity, Cavadini writes that “when we look back on the fatherhood to try to clarify or objectify or specify it, we see, in a way, nothing. We see an effacement rather than a claim; a hiddenness rather than assertion; silence and not speech….”

This thematic of kenosis as a theological datum is continued in Jean-Luc Marion’s chapter “Kenosis, Starting from the Trinity,” which supplies a somewhat oblique dialogue with Hegel on the pain of God by way of a biblically saturated and contemplative meditation on kenosis. Marion’s interest is to protect the mystery not only of the various Scriptural accounts of variations on the theme of kenos/kenon but even more fundamentally the Trinitarian reality to which the Scriptures bear witness. Marion’s meticulous exegesis of the biblical texts on emptiness more broadly suggests a certain hermeneutical delicacy with respect to the use of ekenosen in Philippians 2:7, insofar as it cannot justly be informed by reference to other New Testament texts. Continuing still the themes of darkness, kenoticism, and mystery, Danielle Nussberger’s contribution, “Balthasar’s Theology of Christ’s Impasse and ‘Dark Night’” makes an intervention in the sometimes contentious debates regarding Hans Urs von Balthasar’s theology of Holy Saturday and the passive descent into hell by recalling the importance of spirituality to doctrinal speculation, an element that has sometimes been altogether forgotten or perhaps misremembered. In effect an act of memory itself, Nussberger’s essay traces Balthasar’s spiritual and intellectual debts to the poetry of St. John of the Cross’s “dark night of the soul,” particularly as it has been interpreted by Constance Fitzgerald as impasse. This notion of impasse signifies polyvalently, with implications both for Christology and the experience of the theologian herself, who moves through apophatic impasse toward a greater dynamism, depth, and creativity of thought.

In keeping with Cyril’s own philosophical bent, many of the essays mark nodes of contact between the disciplines of theology and philosophy. In his “Theology in the Middle Voice: Thomas Aquinas and Immanuel Kant on Natural Ends,” Corey Barnes draws together what he reads as cognate themes and problematics surrounding Thomistic final causality and Kantian natural teleology. His methodology for drawing these figures together is double, namely by way first of constellated historical eras—here specifically medieval scholasticism and Enlightenment—in the style of Walter Benjamin’s On the Concept of History, and second, through appeal to Cyril O’Regan’s project of middle-voice genealogy in Gnostic Return, borrowed at root from antique Roman rhetoric. The first methodological move liberates Aquinas and Kant from a potentially myopic focus on historical context that would restrict the thought of either to the bygone past, while the second secures a position between strictly disinterested genealogy and (post-Nietzschean) high genealogy, which operates under the assumption that all discourse is fundamentally interested and thus inseparable from power plays. Without claiming a relation of dependence between Thomas and Kant, Barnes productively draws these thinkers into a mutually illuminating dialogue on causality.

As one might well expect, Hegel features prominently among these more philosophically oriented contributions. Included in this category are the thematically similar but materially distinct essays from William Desmond and David Walsh. Desmond’s “Haunted by Heteronomy: Cyril O’Regan, Hegelian Misremembering, and the Counterfeit Doubles of God” offers a favorable appraisal of O’Regan’s rich contributions to scholarship on Hegel’s philosophy of religion, particularly in Anatomy of Misremembering and Heterodox Hegel, alongside some shorter (review) articles, prioritizing issues surrounding his own notion of the counterfeit double and the operation of misremembering, insisting throughout that the preservation of divine transcendence is non-negotiable. The thematic of the counterfeit God—Hegel’s “God,” whose irreducible otherness is radically relativized to “self-completing immanence”—especially comes to the fore, particularly the paradoxical intimacy of the false representation with the original and the phenomenon of the “perfected double,” the conceptual perfection of which may turn out to disclose rather than to disguise its own spuriousness.

David Walsh’s “On Hegel: Sorcerers and Apprentices” presents a sustained study not directly of O’Regan’s reception of Hegel but rather of Eric Voegelin’s, which amounts to a cleverly slantwise critical engagement with O’Regan by other means. Voegelin operates in this essay as a double stand-in. First he substitutes for Walsh himself, insofar as Voegelin’s trajectory with respect to his reading of Hegel is one of dramatic denunciation that warms gradually to the recognition of affiliations and even filiations with Hegelian and Schellingian strands of German Idealism. Second, Voegelin might be thought to substitute for O’Regan’s mode of critique of Hegel. Walsh argues fundamentally for a hermeneutic of charity and generosity rather than suspicion vis-à-vis Hegel, in his reassessment of Hegel in a light more positive than not. He reconfigures stock interpretations of Hegel by allowing for a sustained valuation of history as having ongoing importance rather than eventual consummation into obsolescence, the possibility for a genuine transcendence in Hegel’s philosophy of religion, and the sense that Hegel’s “system” was neither ossified nor hyperbolized, but actually a dynamic organic whole that grew through the annual lecture additions that “came to overwhelm the margins of the ‘system’ which, it turns out was only a syllabus for a viva voce performance.”

Andrew Prevot’s essay, while acknowledging the centrality of Hegel as an interlocutor with modern Christian theology, prioritizes Heidegger’s place in what he terms the philosophical “counter-canon” of seductive but ultimately duplicitous figures with which Christianity must contend. He first considers the methodological role of philosophical contestation in Christian theology in general, which must move beyond polemic into substantial engagement (Hans Urs von Balthasar is a prominent interlocutor here), and in Cyril’s performance of Christian theology in particular. Second, he turns his attention to specific texts in Cyril’s œuvre that deal explicitly with Heidegger, including review essays, book chapters, and the heretofore unpublished manuscript drafts of the second volume of Anatomy of Misremembering on Balthasar’s contestations with Heidegger. Finally, Prevot accounts for O’Regan’s engagement with contemporary Christian thought that bears some degree of Heideggerian influence, namely that of Jean-Luc Marion and William Desmond.

While Cyril is perhaps most well-known for his challenging theological works, his students, both graduate and undergraduate, know him also as a patient, deft, and deeply generous teacher. Todd Walatka’s chapter, “Delighting in the Truth: St. Augustine and Theological Pedagogy Today,” provides an appreciation of Cyril’s theological pedagogy by means of an analysis of book four of St. Augustine’s classic De Doctrina Christiana. Walatka suggests that Cyril’s mode of teaching evinces a perceptiveness with respect to diagnosing error alongside an equal spirit of generosity that would render his “opponents” in their best possible light, a sensitive attentiveness to the needs of a given audience such that even the most erudite or cerebral points get communicated effectively (i.e., not just a performance of erudition for its own sake), and the way in which the life of the teacher himself or herself allows the luminosity of Truth to illuminate it and even spill out over the borders of the self to illuminate the lives of others.

Continuing with the more pedagogical theme, Brendan Purcell considers the kind of wide-angled multi-disciplinary formation Cyril might well have had as a student at University College Dublin in the 1970s that arguably formed his intellectual trajectory along three particular lines: first, the privilege of interdisciplinarity; second, the performance of acts of memory that would stand against the breach of cultural amnesias; and third, the incorporation of Russian religious thought into his work, particularly the kenotic theology of Sergei Bulgakov. He traces these themes through an outline of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s novel The Red Wheel.1 Purcell sees Cyril alongside both Solzhenitsyn and Voegelin as offering an urgently needed alternative to yet another moribund system of thought.

Sr. Ann Astell’s “O’Regan as Origen in Alexandria” offers an analysis of some of Cyril’s poetry, particularly a selection from his unpublished cycle Origen in Alexandria. Punctuating poetic analysis with details of Cyril’s early family life, Astell provides a sophisticated argument—including the observation of the suggestive anagrammatic potential at play in their names—that Origen and O’Regan operate as something like doubles for one another, since both theologians across time and geographic space bear sometimes contesting obligations to orthodoxy and to experimentation. In particular, Astell’s treatment of the poems brings out themes of origin, place, identity, paternity, spirit, and the nature of art and especially language itself, insofar as it bears multiple registers of signification, with biblical images and text interspersed both with mythical figures and ancient rhetoricians. These variously assumed “impersonations” of such myriad voices are employed by the speaker of the poems as a means to deeper self-knowledge, “an opening to love, compassionate confession, and praise.”

The final two essays, from Jay Martin and Anthony Sciglitano, Jr., consider in quite different ways the corpus of Cyril as a whole, prioritizing, respectively, the implicit place of love within his œuvre as precondition for diagnoses and argument, and a unified commitment across his writings to the rehabilitation of the post-modern in Catholic theology. Martin’s “‘As love, the giver is perfect’: Love at the Limit in the Thought of Cyril O’Regan” takes its title from a line in Gnostic Apocalypse: Jacob Boehme’s Haunted Narrative. He offers a reading of Cyril on the theme of love through a lens of Lacanian psychoanalysis in general and Lacan’s commentary on Plato’s Symposium in particular. Despite there being no explicit theology of love in Cyril’s work, Martin suggests provocatively that love is the “hidden hiddenness” that operates below the surface even as a (if not the) fundamental means by which O’Regan diagnoses and adjudicates the theological viability of competing or counterfeit discourses. In sum, O’Regan’s hermeneutic is demonstrably agapeic, a claim that Martin plots largely along Johannine and Irenaean lines but also complicates by his correlation of agape with eros. By situating Cyril’s diagnostic project within the psychoanalytic register of desire, Martin’s essay suggests ultimately that the agapeic is itself radically transformed in Cyril’s thought precisely insofar as ordinary desire is conformed to the highest gospel imperative of love of God and love of neighbor.

Finally, Anthony Sciglitano argues that the sum of Cyril’s work thus far suggests that post-modern Catholic theology is not only possible but also desirable, and, moreover, that Catholic ecclesial existence is a genuinely viable option in post-modernity. His essay draws out the multiple modes of argument that Cyril employs across his writings, which include lending explicit or implicit support to theological formulations that allow for plural vision as well as repudiating thinkers who “(a) render theological pluralism impossible, (b) render theology impossible, or (c) eliminate or derange Christian doctrine and forms of life under pressure from modern intellectual assumptions and regulations that frequently act as stipulations rather than arguments.” The essay demonstrates clearly that Hegel’s revisionist and ontotheological interpretation of Christianity is non-identical with traditional Christianity; the latter is thus more resistant to the post-modern critique, which would mistake one isomorphically for the other. This claim is reinforced by a thorough account of O’Regan’s invocation of Christian Narrative Grammar against Hegelian metanarrative, which allows not only plural formulations and frank admissions of epistemological finitude in the face of the ever-greater mystery of God, but also accommodates coherence between particular points of doctrine, Christian spiritual practices and forms of life, and a vigorous doxology.

In addition to the fine essays included here, we are also extremely fortunate to be able to publish in this volume a selection of Cyril’s original poetry. It amounts to quite a small percentage of the massive poetic work he has produced over the course of his writing life, poetry that occupies a primordial space prior to the philosophical and theological studies for which he is better known.2 On the whole, O’Regan’s poetry is insistently somatic, the images unapologetically raw and solid but rendered in language stunningly lyrical, delicate, and rich with understated allusions not only to biblical and classical literature but also to other modern poetry, literature, and philosophy. Included in the epilogue to An Apocalypse of Love are three original and strangely prescient poems, two from his collection Origen in Alexandria (“On the Nile” and “Waiting for the Barbarians I,” both discussed at some length in Astell’s essay) and one long narrative poem on the violent execution of Marguerite de Porete, “Requiem for Marguerite (d. 1310),” taken from the collection Poems: Sacred and Profane.

In “On the Nile,” the speaker of the poem admits his own contingency and the potential of total self-erasure, even as the words of the poem themselves become lexically fixed in the very act of writing: “If the world is a sketch/In the possible, it may/Be I am never here, was not/There, fated only to remember/Another’s notes and words/In the fog of the never happened” (lines 28–33). “Waiting for the Barbarians I” is a nod to the poetry of Alexandrian native and poet Constantine Cavafy (1863–1933), which likewise tends to overlay mythical elements on images drawn more immediately from the surrounding milieu of the Alexandrian desert.3 While Cavafy’s orators, consuls, praetors, emperor, and senators seem to have received and internalized the revelation like Godot’s that the barbarians have not come and may not ever come, the denizens of O’Regan’s silent city in his first “Barbarians” installment wait still, choking on bones. Those in his “Waiting for the Barbarians II,” however, “say/The unsayable. They are already here/They are our souls turned inside out” (lines 12–14). “Marguerite” implicitly connects the corpus of its namesake’s The Mirror of Simple Souls, itself a mystical meditation on divine love, with the corporeal nature of her burnt and broken body, her corpse, which post-figures that of the suffering Christ, unveiling love and beauty even or especially in its disfigurement:

But inexplicable this finalizing of flesh

to paper curling at the edges, first brash

yellow, then sullen brown, dull black

to end in no color at all, ready

to fly to the blue beyond the steady

chattering of windless morning,

this folding in which bones see

and the tempest of ash sniffs

the apocalypse of beauty. (lines 7–15)

Here and throughout, O’Regan’s poetry self-consciously queries the fragilities and vulnerabilities of bodies and language together, in a medium within which, in Cyril’s own words, “logocentrism is broken in the name of a broken truth which is our only hope.”4

Words are odd things indeed, as T.S. Eliot famously reminds us in The Four Quartets,5 straining, cracking, breaking, slipping, sliding, perishing, decaying, and otherwise unrepentantly restive with respect to fixed or exhaustive meaning, particularly when met with the (im-)possibility of translation. When this collection was first conceived, for example, we initially considered taking its title from the Irish word “agus,” which means “and,” and titling the book Agus & Agus. The original title, though probably impenetrable to the casual reader and certainly absolutely dreadful for market considerations, did have the benefit not only of providing a definitive nod toward O’Regan’s Irish identity, but also of being maximally evocative on several other fronts. First, it is self-consciously grammatical as a series of three copulas, indicating his constitutively Yale school interest in depth and narrative grammar, deformative grammars of Gnosticism, grammars of the theological tradition, and so on. Second, the copular by definition connects and joins, as O’Regan’s work straddles disciplines and opens up avenues which may have been previously narrowed or even closed, whether in the registers of theology and philosophy, religion and literature, fidelity to tradition and speculation, fides and ratio, poetry and prose, reading and being read, academic theology and sanctity. Third, the peculiar formulation of “and & and” gestures not only to the facility and inventiveness with which Cyril employs the English language, but also his willingness to unsettle rigid logocentric patterns that presume to speak beyond their competence. Fourth, it is suggestive of the confirmed fact that Cyril’s work is deeply viable and generative, somehow simultaneously productive and yet also self-erasing, as it reproduces in those he influences (especially current and former students) something recognizable of his range, tone, and vision, but never allows or permits mere repetition. His mark indeed is indelible but does not blot out. Fifth, and finally, O’Regan is a distinctly fecund theologian insofar as his general modus operandi is unrelentingly expressive, where something more can always be said—though the mystery deepens in direct proportion to the speech—in his efforts to articulate the ever-greater reality of God as infinite mystery.

For the sake of simplicity, however, we opted ultimately for the slightly more accessible but no less apt title, An Apocalypse of Love. After all, the collective impression of these essays, when taken together, is that what is revealed or unveiled indeed is precisely love as the unifying if non-categorical force both of O’Regan’s life and work as an academic, scholar, thinker, public intellectual, mentor, teacher, advisor, Catholic, and friend. The act of knowledge is at root an act of love. As Hans Urs von Balthasar suggests in Theo-Logic I: Truth of the World, objects and persons become known when they receive the gaze of the one who looks upon them with loving kindness:

This special gaze, which is possible only in the loving attention of the subject, is equally objective and idealizing. That these two qualities can be compatible is the grand hope of the object. It hopes to attain in the space of another the ideality that it can never realize in itself. It knows or guesses what it could be, what splendid possibilities are present in it. But in order to develop these possibilities, it needs someone who believes in them—no, who sees them already existing in a hidden state, where, however, they are visible only to one who firmly holds that they can be realized, to one, in other words, who believes and loves. Many wait only for someone to love them in order to become who they always could have been from the beginning. It may also be that the lover, with his mysterious, creative gaze, is the first to discover in the beloved possibilities completely unknown to their possessor, to whom they would have appeared incredible. The beloved is like an espalier that cannot bear fruit until it is able to climb up on the sticks and wires that support it…. Unless the knower presented the ideal, the object known would never have dreamed of aspiring to it, or else it would have grown faint because the attempt would have seemed too fantastic. It takes the faith and confidence of the knower animated by love to give the thing known faith and confidence in the truth of the ideal held before it. At love’s bidding, the object ventures to be what it could have been but would never have dared to be by itself alone.6

The interpretive lens that has emerged in the assembly of this volume as a whole is the place and exercise of love in Cyril’s life and thought. He performs love’s bidding. Yet the character of that love remains elusive: sometimes it is the call of the Love who names itself as the God of Jesus Christ and at others it is the undisclosed Love that hovers over the waters. Although his theological style and achievements are indeed as inimitable as they are profound, still they are but his penultimate gift. What transcends theological genius is the intensity of a theological life given over to Love’s bidding, the life of teacher, poet, and friend that has so convincingly made all who know him a neighbor. Cyril proves that, yes, love alone is credible, but that it is also manifestly possible.

1 An earlier version of this article appeared as Brendan Purcell, “Philosophical and Theological Historiography in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Red Wheel,” Claritas: Journal of Dialogue and Culture 3, no. 1, article 7 (2014). We are grateful to Purdue University for permission to reprint this slightly amended version.

2 For an analysis of The Companion of Theseus, another lengthy cycle of O’Regan’s (unpublished) poems, see Jennifer Newsome Martin, “Poetry and the Exculpation of Flesh,” in The Irenaean Spirit and the Exorcising of Philosophical Modernity: Cyril O’Regan and Christian Discourse after Modernity, ed. Phillip Gonzales. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books (Wipf & Stock Publishers, forthcoming).

3 See, in particular, Constantine P. Cavafy, “Waiting for the Barbarians,” in C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems, trans. Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975).

4 Personal correspondence, July 13, 2016.

5 T.S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton,” The Four Quartets.

6 Hans Urs von Balthasar, Theo-Logic: Theological Logical Theory, Volume I: Truth of the World, trans. Adrian J. Walker (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2000), 114–15.

CHAPTER ONE

The Mystery of St. Joseph in the Memory of the Church

A Father Rich in Mercy*

JOHN C. CAVADINI

ACOLLEAGUE (NOT FROM the Theology Department!) once asked me who was my favorite saint.1 When I responded “St. Joseph,” he seemed utterly taken aback and exclaimed, “But we don’t know anything about him! How can he be anyone’s favorite saint?” There was a lot implied in my colleague’s astonished response, and fair enough, since, considered from the point of view of bare facts about St. Joseph’s life, we do not have much to go on (granting, for the moment, that there can be such a thing as “bare facts” about anyone’s life). But how many such “facts” does one really need in order to find a person, even on the horizontal plane of this life on earth, so attractive that one wants to befriend him or her? One need not have a lengthy c.v. at hand to be able to strike up a friendship with someone and to feel one’s life inestimably enriched thereby. The dimensions of personal attractiveness are not easily reduced to “bare facts” about one’s life. Perhaps, too, a mutual friend or a trusted advisor has introduced you, providing a few essential indications of character as the basis for a possible friendship. In such a scenario, the trustworthiness of the friend or advisor introducing you is part of the appeal of the prospective friend. Even more, the perspective of the mutual friend or trusted advisor is already a factor in the potential friendship and may continue as an important part of the friendship as it develops.

In the case of St. Joseph, the trustworthy friend in the analogy is the Church, and the introduction provided is the set of memories of St. Joseph preserved in Scripture. These memories belong to the Church as a kind of personal subject. The Church is, in a way, a collective person—that is, the People of God, whom Pope Benedict XVI calls a “collective subject,” in fact “the living subject of Scripture.”2 He elaborates that “the Scripture emerged from within the heart of a living subject—the pilgrim People of God—and lives within this same subject.”3 The individual authors of the biblical books “form part of” this collective subject, who is, he continues, “the deeper ‘author’ of the Scriptures” on the human level.4 Later on, Benedict explains how this works, making particular reference to the Fourth Gospel and the dynamics of remembering:

On one hand, the author of the Fourth Gospel gives a very personal accent to his own remembrance … on the other hand, it is never a merely private remembering, but a remembering in and with the “we” of the Church: “that which … we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands.” With John, the subject who remembers is always the “we”—he remembers in and with the community of the disciples, in and with the Church. However much the author stands out as an individual witness, the remembering subject that speaks here is always the “we” of the community of disciples, the “we” of the Church.5

He goes on to emphasize that “because the personal recollection that provides the foundation of the Gospel is purified and deepened by being inserted into the memory of the Church, it does indeed transcend the banal recollection of facts.”6 It is, of course, important to remember that the memory of the Church, insofar as the memories contained are scriptural, is inspired. Benedict puts it this way: “This people does not exist alone; rather it knows that it is led, and spoken to, by God himself, who—through human beings and their humanity—is at the deepest level the one speaking.”7

Scriptural memories are, as it were, definitive memories in the overall remembering of the Church that comprises apostolic tradition. The main content of this memory is, of course, the mystery of Christ, the Word made flesh, as Dei Verbum, the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, sums it up:

It pleased God, in his goodness and wisdom, to reveal himself and to make known the mystery of his will (see Eph 1:9), which was that people can draw near to the Father, through Christ, the Word made flesh, in the Holy Spirit, and thus become sharers in the divine nature (see Eph 2:18, 2 Pet 1:4)…. The most intimate truth thus revealed about God and human salvation shines forth for us in Christ, who is himself both the mediator and the sum total of revelation.8

Jesus “completed and perfected revelation,” and “everything to do with his presence and his manifestation of himself was involved in achieving this: his words and works, signs and miracles, but above all his death and glorious resurrection from the dead, and finally his sending of the Spirit of truth.”9 Everything in Christ’s life, in other words, participates in the mystery of his person that sums up revelation. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it, “Christ’s whole life is mystery…. From the swaddling clothes of his birth to the vinegar of his Passion and the shroud of his Resurrection, everything in Jesus’ life was a sign of his mystery.”10

It goes without saying that St. Joseph is very much implicated in such a statement. To acquire a friendship with St. Joseph means, therefore, if it is authentic, a deeper acquaintance with the mystery of the Lord, and the more intimate the friendship, the deeper the appreciation of the mystery of the Incarnation. The reverse is also true. The more one has accepted the invitation of revelation to become friends with the Lord Jesus and through him the Father, the greater possibility there is for an intimate and living friendship with St. Joseph in Christ. For the whole of St. Joseph’s life and identity is saturated with the mystery of Christ, and the mystery of St. Joseph in the memory of the Church is constituted wholly by its reference to the all-encompassing mystery of Christ that it reflects.

Why don’t we take the recommendation of our trusted advisor the Church and strike up a friendship with St. Joseph? Though it is spare enough in detail, what is authoritatively remembered under the guidance of the Holy Spirit is overwhelmingly sufficient as the basis for an intimate and satisfying friendship. We can begin with the two infancy narratives of St. Matthew and St. Luke. They are notoriously different from each other to the point of potential, if not actual, conflict.11 I regard the difference between the two narratives, as uncomfortable as it can feel for those who would like an easy reconciliation between them, as providential, for it shows that these two narratives are independent traditions, and yet—astonishingly—they agree on the most essential points. Included among these are some of the most unlikely points, namely, that Mary and Joseph were husband and wife, but that before they began to live together as husband and wife, during their betrothal, an angel announced (in one narrative to Joseph, in the other, to Mary) the conception of Jesus, which, in addition, was said to have taken place through the Holy Spirit, without intercourse between Mary and Joseph or indeed between Mary and any other man.12 It is interesting, at least, that the Gospel of Mark does not identify Jesus as the Son of anyone but God, except when it says, simply, that he is “the carpenter, the son of Mary.”13 These points of agreement are anything but “bare facts,” though they are indeed claims on historical truth. Such matters as the virginal conception of Jesus or the appearance of angels in dreams or otherwise cannot even in principle be historically verified, and yet the independence of the two inspired traditions does verify that these memories are as ancient as any there are about Jesus and are not simply the fabrications of the evangelists. They are as likely (or as unlikely, I suppose you could say) as the truth of the Word made flesh, as the truth of the Incarnation itself, for they are the essential elements of the location of the Incarnation in place and time. The Incarnation is thus distinguished from myth, for it is located in place and time, and yet it is not reduced to mere history (if there is any such thing), for it was initiated outside of history and its significance transcends history. Between “myth” and “history” we find “mystery.”14 And for all the special significance of our developing friendship with St. Joseph, all friendships are located in an analogous domain of mystery, for the interior essence of someone’s truly historically located love is never simply reducible to its location in history, nor does that make an account of it a “myth.”

The Gospels do not tell us much about what Joseph thought about all of this. They do not give us an account of what today we might call Joseph’s psychology, but the Gospel of Matthew does evoke an image of a man with a rich interior life, intent on doing God’s will, always on the lookout for indications of his will, and ready to obey. Matthew recounts that Joseph was disturbed by the discovery that Mary was pregnant, and considered divorcing her, though we are not told whether this was because he thought she must have been unfaithful, or that he was already aware that some mystery larger than human devising had entered Mary’s life, in which he was not sure of his further place.15 Matthew tells us that as a “righteous” or “just” man he decided to divorce her, following the Law, the best indication of God’s will that he knew, yet “quietly,” yielding the benefit of the doubt in so doing to Mary or to God or both, as the Protevangelium of James seems to suggest. In obeying the Law “quietly,” Joseph is obeying both its letter and its spirit, divorcing Mary not as a public vindication of his own person, but as a refusal to claim that he knows God’s intentions fully and as an openness to what they might be. In this, the evangelist is saying, does his righteousness—or, we could translate, sanctity—essentially consist.

We can see that this is true to Matthew’s intentions, for when the angel reassures Joseph in a dream that he should take Mary into his home, he does so without any hesitation. The Gospel of Luke, for its part, does not register even a protest, worry, or anxiety on behalf of Joseph, and we might begin to think that he is an afterthought, merely a narrative or dramatic prop, were it not that the Gospel indicates his lively involvement in his family’s life as husband and father up to and past Jesus’s twelfth year. This sustained involvement is described in more detail than that of any other father in the Gospel of Luke—the father of Jairus being perhaps a suggestive second (cf. Luke 8:40–56) and not counting the fathers who are characters in parables. Luke privileges the reflective “pondering” of Mary, instead of Joseph’s, and provides explicit memories of the thoughts and sayings that proceed from her pondering and return us to it.

But Luke is careful to point out that the angel’s annunciation is to Mary, a virgin who was betrothed, and betrothed explicitly to Joseph. Thus, while Joseph is not consulted, neither is he just an also-ran who happens along at some random point in time. It is not Mary alone, but Mary precisely as betrothed who is addressed, and so her marriage to Joseph is part of the divine plan for the Incarnation and not incidental. In this matter, the Gospels of Matthew and Luke agree, though they bring out the point each in their own way. Neither Gospel is so indiscreet as to try to reproduce the conversations between Mary and Joseph about their marriage and their vocation, though they must have discerned it together, in some manner unique to themselves. The Gospels’ reticence on this point, in a way, verifies that this domain is