5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

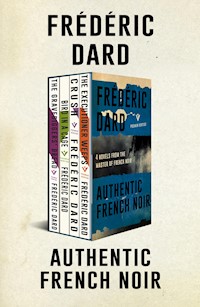

Four pitch-dark, twisty thrillers from Frédéric Dard, France's greatest noir writer 'The French master of noir' OBSERVER Frédéric Dard is the undisputed king of French noir. Authentic French Noir contains four of his most electrifying novels: riveting, disturbing thrillers that propel you into dangerous worlds of obsession and murder. INCLUDES: THE GRAVEDIGGERS' BREAD - Blaise is out of work and down on his luck when a chance encounter with a beautifulblonde has him hooked. He'll do anything to stay by her side, even if it means workingfor her husband, a funeral director. But as everyone knows, three's a crowd. BIRD IN A CAGE - Returning to the Paris neighbourhood where he was raised, Albert seeks to escape lonely nostalgia through an encounter with a mysterious woman. But back at her apartment, a monstrous scene awaits - one that will lure Albert into a dark plot... CRUSH - Bored in her small Northern French hometown, young Louise is captivated by the glamorous American couple who move next door. She soon finds herself working as a maid in their entrancing household, but the shiny surface reveals disturbing flaws, and a dark obsession begins to grow. THE EXECUTIONER WEEPS - Daniel finds a beautiful woman motionless in a ditch, having been run over. Carrying her back to his house on a beach near Barcelona, he discovers she is alive, but she remembers nothing - not even her own name. He falls for her mysterious allure, but when he goes to France in search of her past, he slips into a tangled vortex of lies, depravity and murder.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Authentic French Noir

4 Novels from the Master of French Noir

Frédéric Dard

Contents

To François RICHARD to thank him for the corrections he has given me.

F.D.

The characters in this work, like their names, are fictional. Any resemblance to real people is a matter of coincidence.

F.D.

Contents

PART ONE

1

You have to have waited patiently outside a telephone booth occupied by a woman to really appreciate just how much the fairer sex likes to talk.

I’d already been waiting my turn for a good ten minutes in that provincial post office that smelt of sadness, with only the sympathetic face of the switchboard girl to sustain me, when the lady in the booth finally ended the chatter she was paying for.

As it was a booth with frosted glass, until that point I’d had only her voice to go on in forming an impression of her.

I don’t know why, but I had expected to see someone short, plump and awkward emerge. When she appeared, however, I realized how arrogant it is to think you can put together a picture of a person from their voice.

In reality, the person for whom I stood aside was a woman of around thirty, slim, blonde, with blue eyes that were slightly too large.

If she had lived in Paris she would have possessed the thing she most lacked, namely a certain sense of elegance. The white blouse she wore, and especially her black suit, the work of some elderly dressmaker with a subscription to the Écho de la mode, deprived her figure of eight-tenths of its power. You had to really love women, the way I did, to see that under her badly tailored garments this one had a waist like a napkin ring and admirable curves…

I was watching her walk away when the operator on the line gave a triumphant cry: “You’re through to Paris!”

Being “through to Paris” in this case meant hearing the faint voice of my friend Fargeot peppered with intolerable crackling.

Because of the long-distance call he already knew it was me.

“Hello Blaise! I’ve been waiting for you to call… Well?”

I didn’t answer straight away. In the booth there lingered a curious scent which moved me in a strange way. I breathed it in, half-closing my eyes… It conjured up many indefinable and fragile things… Vague things, things long gone which would never exist again and which almost made me feel like crying.

Fargeot’s voice sizzled like a doughnut in boiling oil.

“Well then, out with it! Hello? I’m asking you…”

“No luck, my friend. The job was already gone.”

His pained silence was renewed proof of the concern he had for me. He was a good guy. He had pointed out the job advertisement, then even lent me the fare.

“What do you expect?” I said consolingly. “I’m always last in the queue when they’re giving things out.”

He gave me an earful.

“You’ll never get anywhere with an attitude like that, Blaise! You’ve got a loser’s mentality. You delight in renunciation… The more life kicks you in the backside, the happier you are. A masochist, that’s what you are.”

I waited for the hothead to finish pouring out his resentment.

“Do you really think this is the moment for psycho analysis, old pal?”

That shut him up. In a different tone, he asked, “When will you be back?”

“As soon as possible. It’s as quiet as a rainy All Saints’ Day in this godforsaken place.”

“Have you got something to eat at least?”

“Don’t you worry, my stomach has hidden resources.”

“Fine, I’ll expect you for dinner this evening. Don’t lose heart, Blaise… Are you familiar with Azaïs’s law?”

“Yes, life is split fifty-fifty between troubles and joys… Assuming that’s right—and since I’m thirty now—that would at least suggest I’m sure to live to sixty!”

With that I hung up because the bell signalling the end of my three minutes was sounding in the earpiece.

Turning round to leave the booth, I felt something odd under my feet. It was a small crocodile-skin wallet. I picked it up, thinking to myself it was sure to contain anything but money. Before now chance had thrown purses in my path at moments when I was damned glad to find them; so far, though, they had contained nothing but devotional medals, trouser buttons or worthless foreign stamps.

Nevertheless, I slipped it into my pocket and went to pay the telephonist for my call, all the while pondering the possible contents of my find.

I made a swift exit from the post office… The station wasn’t very far away. I had nowhere else to go, so I made my way there quickly. I was putting off going through the wallet just for the hell of it, so that I could enjoy a few delicious moments of hope. But once at the station, instead of getting my ticket home I hurried towards the toilets.

Feverishly opening the wallet, the first thing I discovered was a bundle of eight 1,000-franc notes folded in four.

“Blaise, my boy,” I thought. “You’ve won the consolation prize.”

I continued my investigations. From the other compartments I dug out an identity card in the name of Germaine Castain. It had the blonde woman’s photo glued to it. In it she was younger and less pretty than a few moments ago… I looked at the picture, suddenly captivated by the woman’s sad expression.

In addition, I found a tiny photo in the note section. It showed a man of my age, with heavy features. That was all the wallet contained. I was on the verge of throwing it into the lavatory bowl, having withdrawn the providential money first of course, when I remembered the woman’s large, melancholy eyes…

I haven’t always been very honest in my life and scruples have never kept me awake when I’ve been tired; however, I believe I’ve always been a gentleman when it comes to ladies.

I came out again with the wallet. An employee was glumly sweeping the tiled floor.

I went up to him. “Excuse me, do you know a lady called Germaine Castain?”

“Rue Haute?”

The card did indeed have this address on it. I gave him a cursory nod.

The employee waited for me to go on, leaning on his broom. He had a worn, infinitely bored expression.

“Does… er… does she live on her own?” I asked after a moment’s hesitation.

The second question seemed to surprise him.

“Of course not,” he said, sounding almost reproachful. “She’s married to the undertakers.”

It was my turn to be astounded.

“To the what?”

“To the underta—that is, to Castain, the director. You must know Castain? He’s a right bad lot, another one.”

The tone in which he’d said “another one” implied a great deal. I could see that for this poor drudge the world was made up of “bad lots”.

“How do I get to Rue Haute?”

“Go across Place de la Gare… turn right into Rue Principale… straight on until it begins to go uphill. From that point on it’s called Rue Haute.”

I gave him a friendly little gesture of thanks and left, with the man’s doubtful look fixed on my back.

When I’d been told at the rubber factory that the job I was going for had already been filled, my initial reaction had been one of intense relief. Provincial life does nothing for me; quite the reverse, it drags me down. Striding along the narrow streets of the town, I’d had the feeling I was plunging into a tunnel, and the idea of living here had filled me with terror. Only afterwards, on realizing that I had no job and no future, had I truly regretted arriving too late.

I chewed on my bitterness as I strolled across to Rue Haute. So what force for good was driving me to go and give back the wallet? To me the 8,000 francs were a godsend, whereas they wouldn’t make a dent in the budget of that ill-turned-out little middle-class housewife. However much I thought about it, I couldn’t understand my attitude.

Chance was kind enough to give me the wherewithal to get by for a few more days and I was declining the windfall? Was it from a need to shock the woman in the nasty black suit? Or…

With hindsight, I think my crisis of conscience owed more to the town than to Germaine Castain. I needed to create a happy memory to combat the disillusion aroused in me by this smug little place.

After a moment I noticed that Rue Principale was beginning to slope steeply upwards and an enamel plaque told me it was already Rue Haute.

Midday was striking just about everywhere in different tones. There was a lot of activity in the town’s main thoroughfare. It was awakening a little from its accustomed lethargy. On the opposite pavement I spotted a mean little black shop whose door was decorated, if that’s the right word, with a wreath painted in moss-green. White letters announced “Funeral Director”.

I stopped, undecided: I could still turn round and go and catch my train in peace.

Then I noticed a small, dirty, sallow man lurking behind the windowpane, eyeing the passers-by as if they were the potential dead, which of course they were.

“The husband,” I said to myself.

He looked like an old, sick rat. Life couldn’t be much fun for the blonde with a companion like him.

The man gave off a whiff of nastiness. That was what decided me, I think. The possibility of pushing the door handle, the chance to get inside the lair and see a pretty woman with an air of resignation about her was easily worth 8,000 francs.

As I crossed the road I remembered the photograph inside the wallet and thought to myself that the blonde woman didn’t necessarily want her husband to find it there, so I took it out of the compartment and slipped it into my pocket. Then I went up to the door and drove the yellowish little man back into the interior of his shop. The inside was even more wretched than the outside. It was cramped, dim, lugubrious and it smelt of death. There were death notices on the walls, along with coffin handles, crucifixes in metal or pearls, marble plaques with coats of arms, and artificial flowers, which together made the place look rather like a fairground shooting gallery. I stopped, looking at the small, yellowish man. He had grey hair, lying flat, a pointed nose with a red tip, and keen eyes. His thin lips twisted into what he hoped was a welcoming smile.

“Monsieur?”

“May I speak to Madame Germaine Castain?”

That took the wind out of his sails. Clearly no one had ever come asking for his wife. I thought he was going to ask me for an explanation, but he thought better of it and went over to the small door at the back.

When he opened it a smell of fried meat came out, tickling my taste buds.

“Germaine! Have you got a moment?”

From his voice I sensed he was not tender towards his wife. With pounding heart—God knows why—I stared at the door.

She had changed her black suit for a printed skirt which suited her a great deal better. Over it she had tied a little blue apron not much bigger than a pocket handkerchief. I found her a hundred times prettier done up like this.

“Monsieur would like to speak to you,” Castain rasped.

She flushed, and looked at me fearfully. I guessed from her expression that my appearance seemed vaguely familiar but that she couldn’t place me.

“I found a wallet which belongs to you,” I murmured, pulling it out of my pocket.

She turned slightly pale.

“My God,” she breathed. “So I’d lost it.”

Naturally the coffin salesman lost his temper.

“You’ll never change, will you, poor Germaine…”

He grew talkative.

“How can we ever thank you, monsieur? Is there money inside?”

“Yes.”

He snatched the wallet out of his wife’s hands. Her pallor intensified. It was a damn good thing, I thought, that I’d removed the photo of the guy with the thick-set features. For the moment it was a lot better off in my pocket than in Madame Castain’s wallet. Sure enough, the undertaker thoroughly examined the crocodile-skin case.

“Eight thousand francs,” he sighed. “Well, you’re an honest man, monsieur, that’s for sure.”

The heartfelt thanks made me laugh.

“Aren’t you going to thank monsieur, then?” exclaimed Castain.

“Thank you,” she stammered.

She looked as if she was about to faint.

“There’s really no need, anyone would have…”

“Where did you find it?” asked the husband.

His voice was filled with suspicion. The woman threw me a desperate glance.

“OK, sweetie,” I thought. “You don’t want me to mention the telephone booth.”

Immediately I had made the connection between the little photo and the telephone call.

“I can’t tell you,” I replied. “I don’t know the town.”

I finished with a vague gesture. “Over that way, in the street.”

I will never forget the look of wild gratitude she shot me. I had just made her life worth living again. Castain insisted on offering me an aperitif. I didn’t object. It had been quite a while since I’d had a sniff of alcohol and I was in dire need of a drink.

We left the shop, went along a narrow corridor dimly lit by one feeble bulb, and emerged at last into a dining room so sad it made you want to scream.

“Please, do sit down.”

I would have preferred to get the hell out of there. This dining room was like a tomb. It was long and narrow and its only daylight came from a sort of hatch in the wall, opening onto a courtyard. The furniture was neither better nor worse than that usually found in the homes of small provincial shopkeepers, but within these walls with their yellowing wallpaper, the colour of incurable diseases, each piece as good as conjured up some funerary ornament. How the devil could a woman live in such a place?

Castain sat me down and poured me a glass of a bilious liquid he ingeniously dubbed “house aperitif”. It was bitter and sugary at the same time and I had never swallowed a medicine as ghastly.

I was secretly cursing myself for my honesty while the graveyard rat was congratulating me on it. Deep down the situation was not without its piquancy.

“You’re not from round here, then?” the yellowish man asked.

“No… Paris.”

“Are you a sales representative?”

“I’d like to be… That’s actually the reason I came to your town. A friend told me that the rubber factory was looking for a salesman. I’ve already worked in the chemical industry.”

There was a dark disapproval in his voice when he asked, “In short, you’re out of work?”

“In short, yes. Two years ago I left my job in Paris to work with a scoundrel who claimed to be setting up a building firm in Morocco. The few assets I had went into that. For two years I kicked my heels in a little office in Casablanca. It was unbearably hot and I never saw a soul, not even my associate… I came back last month. I had tried to find a job over there but with what’s going on now the Frenchman is a commodity it’s increasingly hard to find a place for… To cut a long story short, here I am back in France, out of money and out of work. It’s no joke.”

“Are you married?”

“No, fortunately.”

I had spoken without thinking. I quickly turned to look at the young woman standing motionless against the door frame.

“I mean ‘fortunately’ for the woman who might have married me,” I clarified.

She smiled at me. It was the first time, and to me it was as if a ray of light had come over the room.

“No success here then, with the job?” asked the undertaker.

“They’d just taken on a candidate who was quicker than me.”

“Would you have liked to work in this area?”

“I’d like to work anywhere, especially here. I like this area. I just love the provinces.”

That was all nonsense, obviously. I was only saying it to please them.

He took hold of his disgusting bottle of “house aperitif”.

“Another little teardrop?”

He certainly spoke like a funeral director.

“No, really, I never usually drink.”

He expressed his clear approval by lowering his eyelids briefly.

“You are so right… I understand. In my house, my father was an alcoholic and it was Achille Castain who paid the price.”

And he added with a certain pride which, nevertheless, failed to impress, “Achille, that’s me.”

The moment had come to take my leave. The woman had scuttled back to her stove.

“Well, Monsieur Castain, it’s been delightful to meet you.”

“Thank you again.”

We shook hands before we reached the shop doorway. His was dry and cold.

He didn’t let go. His fingers were like the talons of a bird of prey.

“I wonder, monsieur…”

I realized then that I hadn’t introduced myself.

“Blaise Delange.”

I waited for him to continue, but he seemed to hesitate. There was something uncertain in his small, quick eyes, which must have been unusual for them.

“Did you want to say something?”

He was looking me up and down with great care, completely unabashed. I refrained from telling him where to get off.

“I may have a proposition for you.”

“For me?”

“Yes, does that surprise you?”

“God… that depends on what it entails.”

The blonde woman had come back from the kitchen, having poured a little water over her roast veal.

“Are you going?” she asked.

Her voice contained a vague regret. Her large eyes appeared even more sorrowful.

“I’ve got a train to catch.”

But her husband interrupted. “Do you know what I was thinking, Germaine?”

He was addressing me, in fact, but talking to his wife simplified matters.

He cleared his throat and, without looking directly at me, went on: “I need someone to assist me because my health isn’t all it could be. Since monsieur is looking for a job… it seems… until something in your line comes up…”

I swear I wanted to laugh. That was really the most extraordinary suggestion anyone had ever made to me! An undertaker, me? I saw myself with a cocked hat and buckle shoes, black cape over my shoulder, walking in front of a funeral procession. No, it was too ridiculous.

I stopped myself from laughing, however.

“Assist you in what?” I asked. “I don’t know anything about your profession, Monsieur Castain, except that it’s not exactly a bundle of laughs.”

“You’re making a mistake there, it’s as good as any other.”

I’d offended him. Like everyone with stomach problems, he was over-sensitive.

“I’m not denying that, but I still believe yours demands certain, er, talents that I in no way possess.”

“But which you can acquire. Of course there’s no question of you organizing funerals, but our trade includes a certain sales side which tires me out. Our work, you see, begins with a catalogue. We sell tangible things, Monsieur Delange. Are you afraid of the dead?”

In a flash I went through the list of all the dead people I knew.

“I wouldn’t say afraid… I… they intimidate me.”

“That timidity is easily got rid of, believe me. I was like you to begin with. And then you get used to it.”

He shrugged his shoulders.

“I’m well aware that the layman imagines all sorts of things about our profession. Or rather, he finds it hard to admit it’s an ordinary profession. Yet I can assure you that gravediggers’ bread tastes just the same as other people’s.”

At that moment the telephone rang in the shop and he went to answer it.

I found myself alone with his wife. I took out the photograph, which was still in my pocket, and handed it to her discreetly.

“Here, before I go…”

She hastily slipped it into the neck of her blouse.

“Thank you,” she stammered.

For some time we stood looking at each other without a word. She was the kind of woman you long to see slightly unhappy so that you can console her. The click signalling the end of the phone call sounded.

“Stay,” she breathed.

Did she really say that? I’m not sure. Even now I wonder whether I guessed at rather than heard the word. It set my blood on fire.

Castain returned, with a satisfied air.

“That was a call about a client,” he crowed. “The good thing about our profession is that we’re protected against unemployment, you see. Of course, we had a little dip when penicillin came along and these new sulphonamides aren’t doing us much good, but other than that… What do you say?”

I sensed the woman’s intense eyes on me. I didn’t dare look at her.

“We can always give it a try,” I sighed.

2

He wasn’t offering me a king’s ransom, of course: 20,000 francs per month, plus lunch and a ridiculous percentage on business I brought in above a certain value.

Castain assured me that I could, in this way, increase my monthly salary by some 1,200 francs. Taking into account the much-vaunted midday meal, that would add up to a decent sum in total.

The undertaker assured me that in this backwater I could live like a prince on such an income. He knew a small hotel where I could find lodgings at a good price. In short, the more reluctant he saw me to be, the more enthusiastically he praised this new existence.

“And, after all,” he finished, “if things don’t work out we can still always go our separate ways, can’t we?”

I agreed.

“Right. So you’ll go to Paris and come straight back with your trunk?”

I’d thought to myself that if I set foot in the capital again I’d never be able to tear myself away to come and bury myself—or, rather, bury other people—here in the back of beyond.

“It’s not worth it. I’ve a friend who can send my things on. If you’ll permit me, I can phone him.”

“Call him right away.”

Castain was delighted. His wife set another place while I was waiting to be connected. The delicious meat smell got my juices going. I hadn’t eaten very much for some time and a proper meal was rather tempting.

I got through to Fargeot and explained very briefly that I had found a job to tide me over.

“In what line?” He sounded worried.

“At the funeral director’s!”

“No, be serious.”

“I’m deadly serious… I’m going to sell coffins, my old pal. You’d never imagine what nice ones you can get.”

As I spoke, I was looking at the samples pinned to the walls of the sinister shop.

“So much so,” I went on, “that it breaks your heart to stick them in the ground.”

We agreed arrangements to settle the bill for my boarding house in Boulevard de Port-Royal and he said he’d see about sending on my suitcase that same day.

With my mind at rest over this, I joined my hosts at table.

It was a convivial meal. Castain was overexcited by my presence.

“By the way, do you drive?”

“Yes, why?”

“I’m thinking of the hearse. I have someone for the funerals, of course, but he works as and when. Aside from those, there are private transfers, if you get my drift. Changes of tomb, deliveries to the morgue…”

Germaine Castain was giving me glances of silent encouragement. She sensed how barbaric such language appeared to me and was doing her best to sweeten it. I think she understood that I had accepted because of her. That made things easier between us in one way. But it made them a hell of a lot more complicated in another!

I was impatient to find myself alone with her for a decent length of time so that I could ask her about her life. This strange couple concealed a mystery, and I was eager to find it out.

But the hoped-for tête-à-tête didn’t happen that day. In the afternoon Castain took me first to the Hôtel de la Gare where, on the strength of their friendship, he persuaded the manager to give me a room overlooking the street for the price of one on the railway line.

Next we went to see the clients who had phoned that morning. These were well-to-do people, the owners of a sawmill, if I remember correctly. The grandfather had died in the early hours. Before crossing the threshold of their house, my boss gave me a lesson in applied psychology.

“You see, Delange,” he said. “We can’t expect anything on the business front here. It will be the second-lowest category and a pauper’s coffin.”

“Why do you foresee that?”

“The fact that it’s the grandfather. That’s ten years now they’ve been spoon-feeding him and changing his sheets three times a day. If they could they’d stick him in the dustbin. You’ll see.”

He rapped on the door with the old brass knocker and a wrinkled maid came to open the door, weeping for form’s sake. She led us to the room where the family were receiving neighbours to view the deceased and recounting his death for the twentieth time.

The dead man’s son, a tall, red-faced fellow with hair that was already white, took us into the dining room. Without asking, he set three glasses on the table and reached for an old bottle of Burgundy which had been brought out of the cellar to await us. While the master of the house was busy looking for a corkscrew, Castain whispered in my ear: “It’s these bastards that are killing me with their obsession with offering drinks. And you can’t refuse or they get annoyed.”

“Let us move on to the cruel necessities of the occasion,” he intoned, words he clearly had off pat.

The feigned sorrow on his face made me giggle. He noticed and shot me a furious glance. From his briefcase he was extracting a small portfolio containing photographs of caskets, catafalques, crucifixes and other funerary accoutrements.

“What do you have in mind, Monsieur Richard?”

The big red-faced man shook his head.

“Just what’s strictly necessary,” he declared straight out. “You knew my father? He had simple tastes.”

Another knowing look from Castain. In his eyes was written in block capitals: I TOLD YOU SO.

He nonetheless sighed: “Do you think so?”

When it came to talking business he was a real idiot, I thought. That got me angry.

“Monsieur Richard,” I started. “The strictly necessary is something you can do yourself. You have planks—all you need to do is put four of them together and you’ve got it. What we, on the other hand, provide is a way of paying one last tribute to your father, and of proving to your nearest and dearest that you considered him more than just a burdensome old man!”

Castain was aghast. His mean little eyes grew huge and I saw myself distorted in them as in some diabolical mirror. His right shoe was desperately searching for my left, which I’d carefully tucked up onto a bar of my chair. As for our customer, after jerking upright in his seat, he suddenly appeared very downcast.

“To be sure,” he murmured. “To be sure, I’m not saying…”

I’d got into my stride, and to be honest I could sense the fellow was in my thrall. Plus, for my own part I was keen to savour the humour of this unusual profession.

“But Monsieur Richard, you are saying… and you’re saying, ‘what’s strictly necessary’. I won’t do you the insult of believing that you’re motivated by saving money in circumstances like these, and you won’t do me that of thinking that I want to take advantage of your grief. But let’s face up to things. You have just lost the one to whom you owe everything. What would people think if they saw you giving him a hasty burial, hmm? You know them. Always ready to gossip and put people down. They’d say you were ungrateful or—and this would be worse for your standing—they’d say you lack the means to put on a good show.”

That was a direct hit, not to his heart but to his pride.

“You’re right,” he declared.

And, to Castain, “He’s right. And I like people who speak their mind. Does he work for you?”

“Yes,” said Castain, astonished to see how easily I’d triumphed. “He’s from Paris.”

After that he had only to take out his order book and announce the prices. The man who sold planks was ripe for the picking. I think if we’d had a parade of the Republican Guard in our catalogue we’d have sold him them along with the rest.

When we left, Castain said nothing for some time. Irritated by his silence, I provoked him:

“Well boss, how was that for starters?”

He stopped walking. With a shrug of the shoulders he murmured:

“Your methods are a little brutal… But in any case, the results are terrific!”

“Isn’t that all that matters?”

“Indeed. But some people in Richard’s place wouldn’t have stood for it.”

“So? What does that matter, since you don’t have any competition? No, Monsieur Castain, the clientele likes to be chivvied. Most people are bad at making decisions so they’re grateful if you do it for them.”

He wasn’t entirely convinced.

He retreated into sullen silence until we got back. Germaine was minding the shop. She was doing accounts at an ink-stained writing desk. When she saw me her eyes lit up with happiness.

“He’s a winner!” declared Castain, hooking his felt hat with its upturned brim onto a coffin handle. “You know big Richard from the sawmill? He’s a tough guy, eh? Well, he’d won him over in no time.”

I hadn’t anticipated such an outburst of enthusiasm.

“Will you stay for dinner?” suggested the sallow little man.

I avoided looking at the woman.

“No, let’s stick to what we agreed, lunches only. In any case, I’m very tired and thinking of an early night.”

He didn’t insist.

“As you wish… Would you like an advance on your salary?”

“Not for the moment. We’ll discuss it later.”

“All right.”

I took my leave with a vague feeling of guilt towards the woman. In leaving her I felt I was abandoning her deep in a lonely cemetery or in some chamber of horrors where her discreet charm would simply fade away.

The dining room at the Hôtel de la Gare was very conventional, but had a certain good-humoured intimacy about it. This atmosphere made a happy contrast with Castain’s shop. I ate the set menu at a communal table along with some travelling salesmen and a temporary schoolmaster.

After peeling an over-ripe pear, pretentiously called “dessert” on the menu, I felt a need to enjoy my own company in a shadowy corner.

In addition to which, it was still too early for bed. I decided to go to the station to buy something to help me get to sleep, namely cigarettes and magazines.

It was a beautiful spring night, vast and blue, with unknown stars and scents wafting by on the ripples of the breeze. From the hotel doorway I began to breathe the night in almost voluptuously. It reassured me.

I was inhaling for the third time, when I noticed a voice calling me in the darkness.

“Monsieur Blaise!”

I turned to my right. There was a hedge of privet bushes in boxes bordering a terrace. I made out a shape and the light patch of a face. Again the voice called, “Monsieur Blaise.”

I moved forwards then into the shadows and recognized Germaine Castain.

She was standing motionless against the wall of the hotel, beneath the dining-room window. An old coat was thrown round her shoulders, and her hair—perhaps because of the breeze—was in a mess. Her eyes had a strange shine to them. On closer inspection I could see she’d been crying.

“Madame Castain,” I murmured. “What’s the matter?”

Instead of replying she made for the area set back from the square. Here the station concourse formed a cul-de-sac because of the railway track. There was the embankment, the plane trees, the cubic form of a transformer box.

We stopped behind the transformer. All of a sudden my heart was racing. I longed to take her in my arms.

“Why are you crying?”

“I’m not crying.”

“Yes you are.”

She used her fingertips to check.

“Forgive me for calling you Blaise—I don’t remember your surname.”

“Not at all, I’m glad you did. Answer me, why were you crying?”

“Because he’s hit me again!”

I couldn’t believe my ears.

“He beats you?”

“Yes, often.”

I was alarmed. Certainly I’d suspected that life with Castain must be lacking in charm for his wife, but I had never dreamt he was knocking her about!

I clenched my fists.

“That horrible man. Daring to lay hands on you—why does he hit you?”

Her face was serious now. She had regained her self-control and looked thoughtful.

“Because,” she said finally, “because it brings him a bit of relief, I think. The weak take revenge for their weakness on those who are even weaker.”

I asked her the question which was eating me up, and truthfully I didn’t believe I could put it so crudely: “Why the devil did you go and marry that fellow? You’re like chalk and cheese!”

A train passed slowly by at the top of the embankment in a paroxysm of asthmatic puffing. Its red glow set Germaine’s face on fire and I saw that her eyes had an angry glint in them.

“Why does a young girl marry a dried-up old man? Just read one of the stories you see in the magazines. I was young… I loved a boy my own age… he got me pregnant. His family were against our marriage and sent him abroad somewhere so he’d forget me. Ever since I was a little girl Castain had been cornering me in dark places. He took advantage of the situation to ask my mother for my hand in marriage. The dear woman was a poor widow, in despair over the mistake I’d made. She was so insistent I jump at this generous offer that I accepted. Only, you have to beware of devout people. They’re the worst bastards on earth.”

From her lips the word “bastard” took on a wider meaning. It summed up all her rancour, all her immense despair.

I put my hand on her shoulder. She shook me off.

To hide my embarrassment, I asked: “And then?”

“Then, nothing. His age, his position and his feigned generous heart meant that every right was on his side. He began by taking me to see some midwife who specialized in ‘premature births’. I didn’t have the child. Castain won right across the board. He’s always treated me like a dog. Now whenever he feels like it he seizes on the first opportunity that comes along to beat me.”

This story lacked poetry. It was like a drama from a Zola novel that shocks both intelligent people and the vulgar bourgeois.

We remained motionless for some time, without a word. Another train went past and each of its carriage windows lit up Madame Castain’s beautiful, sad face.

“Why haven’t you left him?”

She tossed her blonde hair. I felt a lock brush my face and once again I resisted the desire to hold her close, cradling her pain.

“You see, Monsieur Blaise…”

“You can just call me Blaise.”

“That wouldn’t be proper.”

“OK, no need to say another word about it, it’s all becoming clear. You stayed because one scandal was enough to fill your little life of inactivity, isn’t that so?”

I had spoken harshly. She moved away from me.

“Why are you being unkind?”

“I’m not being unkind, I’m indignant. I like the people I associate with to have some sense of dignity. I think it’s disgusting that you let yourself be beaten like… well like a dog, actually!”

I thought she would run off, but she didn’t even flinch. I went on: “Besides, a little bird tells me you’ve got some compensations, isn’t that right?”

“What do you mean by that?”

“I’m thinking of the photo hidden in your wallet. I’m also thinking of your phone call at the post office, because that’s where I saw you.”

“Yes, I know.”

“If I hadn’t used my head I could have given your undertaker good reason to give you a beating you wouldn’t forget in a hurry, couldn’t I?”

“That’s true… yes. You’re very clever, Blaise, and very sensitive. Your thoughtfulness…”

“Never mind my thoughtfulness! Answer me: you have a lover, haven’t you? A woman who goes to the post office to make calls when she has a telephone at home doesn’t want to be overheard by her husband.”

Her voice sounded strict: “I do have a lover, yes.”

“I’m not reproaching you. I’d even say I approve entirely…”

“Thanks!” she said ironically.

“Who’s the lucky man?”

You may or may not believe me, but jealousy was gnawing at my insides. Yes, I was jealous over this girl I hadn’t even laid eyes on twelve hours before.

“Still the same one,” she replied.

I didn’t understand immediately.

“Huh?”

“Still the same one… the father of the baby I didn’t have.”

My anger leapt to life again, full, vehement.

“When I mentioned your lack of dignity I didn’t think it was that complete. So here’s a pathetic guy who drops you after he’s got you pregnant. He allows you to marry that rotten, dried-up fool Castain, to waste away surrounded by your funeral wreaths, and the swine continues to have his fill of you!”

“Be quiet!”

In a whisper she murmured, “You wouldn’t understand.”

“Please God there’s something to understand!”

“He’s ill. He has been all his life… epileptic fits.”

I said nothing. The problem might have a new complexion to it but in my eyes it remained insoluble.

“So you’re the mistress of an epileptic?”

“So? He’s a man like any other, isn’t he?”

Her cry was so heart-rending that it moved me. I shook my head.

“All right, he’s a man like any other man. A man with a right to happiness. A man with extenuating circumstances. But humanity isn’t pretty, Germaine. You’ll never prevent a normal man from thinking it’s a shame to see a beautiful girl give herself to a sick man.”

I was thinking now that old Castain hadn’t been so wrong to get rid of the child after all; deep inside myself I was making excuses for him.

She was speaking. I made an effort to listen to what she was saying.

“He was handsome. I’d always loved him. People told me he had epileptic fits but I didn’t care. Even when I witnessed one of his fits I wasn’t scared. It was just that at the time of our affair his family used his illness as an excuse to send him away. He had an attack, they injected him with a sedative which destroyed all his willpower. They told him I’d married a very rich old skinflint—Castain is rich. Maurice extended his stay in Switzerland. Years passed. Then his father died and he came back. A few months ago I saw him again. We were irresistibly driven into each other’s arms. It all started again.”

She fell silent. I felt ill at learning all that and decided that the very next day I would clear off back to Paris. I didn’t think I could live somewhere like this.

“Hang on, since your Casanova’s come back, can’t you disappear off somewhere with him?”

“No.”

“Why?”

“Because he’s ruined. His father was riddled with debts when he died. Maurice lives in a garret. He makes a living through photography but it’s a poor living. I… I help him.”

This just got better! Madame had her fingers in the funeral director’s till in order to put food on the cheap pimp’s table! I was sickened. All three of them, Maurice, Germaine and the dreaded Achille seemed like a bunch of spineless cowards and degenerates. Yes, there was a definite lack of oxygen round here.

Something struck me: “Why are you telling me all this?”

“Well, I…”

“Come on, spit it out.”

“Just now, when he’d hit me, I told him I’d had enough of his behaviour. I ran away to… to give him a fright. That’s the first time I’ve acted like this. I hope it’ll make him calm down. But I’m going back.”

“And why did you dare, today?”

“Because of you. Since you’ve been here I feel stronger. It seems to me, and besides you’ve proved it, that you’re my friend.”

“Yes, I am your friend.”

“So I’m going to ask you to do something else for me.”

“Fire away.”

“It’s difficult to say…”

“After what you’ve already confided in me, I can’t imagine what could be difficult to express, sweetie.”

“That’s true. Here goes then. Tomorrow it’s market day in Pont-de-l’Air.”

“Where?”

“Pont-de-l’Air. A big town near here. On Thursdays I take the bus there to do the weekly shopping, because groceries are cheaper there than here. Maurice lives in Pont-de-l’Air.”

“I get it. So Thursday’s the day for your frolics.”

My sardonic tone, more than the word itself, hit home.

She turned on her heel and strode off into the shadows. I was stupefied for a moment, then ran after her. I caught hold of her arm.

“Hey, wait, Germaine! No need to be that sensitive! When you claim a man’s friendship you must expect some bluntness on his part. That’s what distinguishes friendship from love. In love you only use thistledown, in friendship you use horsehair as well.”

She stopped.

“Yes, you’re right… Forgive me, my nerves are in shreds.”

“Not as much as mine are!”

It had just slipped out. She looked at me.

“Why’s that?”

“It may have escaped your notice but I have seriously fallen for you. I’m going to confide in you as well, open a window onto my personality. If I hadn’t seen you at the post office, you could have kissed goodbye to your eight thousand francs.”

She was shocked, of course.

“Oh, that’s what you say…”

“I’m saying that because it’s God’s honest truth, that’s all. A simple clarification in passing. Now, go on—what do you want from me?”

“The row with Achille just now came about because of the market. He announced that it was ridiculous for me to go to Pont-de-l’Air just to make a small saving. I think he must suspect something. I insisted, and he got angry. Tomorrow he’ll prevent me from going, that’s for sure.”

“So you’d like me to go over there and explain things to Maurice?”

“You’ve guessed it. Is that a nuisance?”

“No, not exactly… But are you forgetting that I have a boss?”

“That doesn’t matter. Tomorrow morning you come and tell him your trunk hasn’t arrived and that you have to go and fetch it from Paris. Here, there’s money in this envelope. Take your expenses from it and hand the rest over to him.”

“Understood. Where does lover boy live?”

“His surname is Thuillier. His address is 3, Rue Marius-Lesœur in Pont-de-l’Air—will you remember?”

“Eternally. You can count on me.”

“Good, I’m going home.”

“Would you like me to walk with you?”

“Better not.”

“As you wish.”

She was hopping from one foot to the other, unable to make up her mind to go.

“Have you got something else to tell me?”

“No. Make sure to explain to him that… as soon as I can… and I’ll try to phone him tomorrow.”

I made a little gesture of agreement.

“What are you thinking?”

“I’m thinking he’s a damned lucky man.”

She held out her hand.

“Thank you. Good night!”

“Good night.”

She slunk away under the trees with their sprinkling of fat buds. I felt a bit depressed once she’d disappeared.

The lights had just gone out in the hotel and there was only the night light in the hall. I reached my room without making a noise. It was small, pink, clean and smelt of trains.

I undressed completely and slid between the rough sheets. It was a long time before I fell asleep, however. Whenever a train went by, everything in the room shook even though my window didn’t overlook the tracks.

I tried to imagine the drowsy people passing in a clanking of metal, but for me they were without souls and without faces.

3

The next day at the Castains’ there was no trace of their bust-up the evening before. I arrived to find Germaine polishing the rococo furniture in the dining room and Achille preparing for the Richard grandfather’s funeral.

I told him my friend had been unable to get into my room without a key and that the easiest thing was for me to make a return trip to Paris to fetch my cases. Castain didn’t bat an eyelid, just told me to be quick because he was counting on me for the next day.

I was therefore able to take the bus to Pont-de-l’Air without difficulty.

The place was the replica of the one I had just left. There was the same Place de la Gare, with an Hôtel de la Gare; the same Rue Principale, the same old-fashioned shops and, above all, the same quiet people.

I asked the way to Rue Marius-Lesœur of a small boy, who led me there by the hand. This was a narrow street at a crossroads marked by a flashing light in the middle. It was lined with bulging old houses which were not without character. I set off across the cobbles in search of number 3.

I arrived at a sort of grand town house whose enormous door reminded me of a prison. I rang. A forbidding lady answered. When I told her that I wished to see Monsieur Maurice Thuillier she replied haughtily that I would have to go through the stables and up some wooden stairs.

The young man’s living quarters in fact clearly belonged to a different world from this austere residence. They had been built above abandoned stables now used to store cars. Evidently the owners of the town house were either stingy or of limited means; they exploited every possibility to create an income for themselves by letting the parts of the building which did not impinge on their grandeur.

The wooden staircase creaked under my weight. Its iron rail was wobbly and wouldn’t have withstood the stumbling of a drunken man. The narrow steps led up to a worm-eaten balcony with several doors leading off it.

At the top of the stairs I called out: “Monsieur Thuillier, please!”

The first door was flung open and he appeared. He was a great deal more handsome than in his photo—a great deal more handsome than me as well! That realization struck me straight off.

Tall and athletic, he was wearing corduroy trousers, a red and white checked shirt and sports shoes.

He had dark, feverish eyes, light-coloured hair cut very short, and his mouth was flanked by two deep lines. Thuillier was standing in front of me like a dog ready to bite.

“Was it you calling me?”

“Yes.”

“What do you want with me?”

“If you invited me in I’d be more comfortable telling you.”

I thought he was about to throw me over the rickety banister. But he restrained himself.

“Oh, come in then… You know, it’s not the Ritz.”

“I couldn’t care less.”

That calmed him down. He smiled at me.

“I’ve never seen you…”

“Me neither. There’s a first time for everything though, isn’t there?”

“Who are you?”

“A colleague of Monsieur Achille Castain. D’you know him?”

He was on his guard. His upper lip drew back in a snarl and again he looked like a vicious dog.

The dwelling was in keeping with the man. It was furnished with a mattress laid on the floor and covered with a large cashmere blanket. There was also an ancient table, a very beautiful Louis XIV chest of drawers and a dressing table on which he had placed all the equipment for a photographic laboratory. The walls were almost entirely covered in prints, many of which proved interesting.

I had taken in the layout of the place at a glance. The lodging’s only source of daylight was the glass door. It was dim and thus particularly suited, of course, to a photographer.

Standing square in front of me, hands on hips, Thuillier was looking at me through eyes streaked with red veins.

“Monsieur Achille Castain’s colleague, otherwise known as the undertaker’s assistant. And as well as manhandling the corpses, you dabble in espionage to fill your free time?”

I fought back my sudden desire to bring my fist into contact with his handsome face.

“Any espionage I do is on Madame Castain’s behalf.”

I took out the envelope she’d given me and threw it down on the table.

“Her husband stopped her from coming to be made love to today—would you be so kind as to excuse her?”

I saw the heartbreak in his eyes. He must have been wildly impatient for her to arrive. That was why he’d received me so brusquely.

He stuttered “Eh? What?”

“I told you, there was a row at home last night about Pontde-l’Air. He doesn’t want her to come—probably got wind of something. I was the only means she had of letting you know in time, have you got that?”

He squinted at the envelope.

“What’s that?”

He knew—I could tell from his evasive look—but he wanted to find out if I knew the score.

I didn’t like the guy. He may have been an invalid, but I was quite certain he was an idler of the first order. He wasn’t worth a damn, as he’d amply proved. As a woman in love, Germaine dressed him up in all the fine qualities she wished for in a man; nonetheless he belonged to the ranks of those little good-for-nothings who take advantage of credulous women.

“That,” I said flippantly, “is your week’s fodder.”

He came towards me. “What did you say?”

He thought he could intimidate me, but he could take a jump! I was ready for him, old Maurice. At the first sign of physical aggression, I was resolved to go for him, head first!

“It’s your fodder,” I said. “Dead man’s bread, you might call it. The tithe madame takes from Castain’s corpses.”

He snatched up the envelope, tore it open and pulled out 4,000 francs. A grimace of disappointment twisted that very mobile upper lip.

“Not much, is it? You’d do better to work a dowager on the Côte d’Azur… Germaine does what she can, but with her skinflint of a gravedigger it won’t go far.”

“Bugger off!” he snarled.

“With pleasure.”

I turned to go. I already had one foot on the top step of the wooden staircase when he called me back:

“Hey!”

“Are you calling me or your dog?”

“Just listen for a moment.”

I hesitated, then went back into the room. An unpleasant smell of hyposulphite hung in the air. I hadn’t noticed it at first.

“What?”

“Have you been working for Castain for long? She’s never mentioned you.”

“Since yesterday.”

He thought I was making fun of him.

“Since yesterday?”

“Yes. Are you shocked that Germaine has already confided her intimate secrets to me? I’ve a face which inspires trust in ladies—and I don’t abuse it.”

“Oh you can stop your jibes—they don’t get to me.”

“I’m sure—the thing about guys of your sort is that they’re impervious.”

“Have you said your piece? I’m not insulting you, am I?”

That was the best he could come up with.

“You don’t insult your mistress’s confidant.”

He was white with suppressed anger.

“I don’t give a damn what you think. You can go to hell!”

I took two steps forwards and gave his face a resounding slap. He put his hand up to his left cheek, which was turning red.

We had nothing more to say to each other after that. I took my leave. But just as I was about to go through the porch of the former stables, I heard a horrendous racket coming from his place. I stopped, undecided. The forbidding woman who had opened the front door to me appeared. She was listening.

“He’s having one of his attacks,” she sighed. “He has them more and more often. I tell him he should see a doctor but he sends me packing, saying I’m telling lies. He doesn’t remember anything about it afterwards of course.”

She went back in with a shrug. I leapt up the stairs and froze in the doorway. Frankly, it wasn’t a pretty sight.

Maurice was writhing on the floor, thrashing about like a devil. His eyes were wild, staring, bulging out of their sockets. White froth was forming on his lips and he was bucking, scraping the floor without uttering a sound. This sort of struggle with nothingness had something terrible about it.

And yet I felt no pity for him.

“So that’s the creature she loves,” I mused. “My God, is it possible that such a woman’s every thought is for this poor devil?”

I stepped over Maurice and made my way to the dressing table-cum-laboratory, a Machiavellian notion going through my mind. On the marble, in front of the baths of emulsion, was a Rolleiflex with an electronic flash. I looked to see what stage the reel of film was at. The number four came up in the little round hole when I’d pressed the focusing button.

I set the exposure and plugged the flash into its battery. And then I treated myself to three photographs of the guy at the height of his spasms.

If he called his landlady a liar when she spoke about his fits, this way he’d have firm proof of her sincerity.

I put the camera back on the dressing table. Things were quietening down for Maurice. The jerking was stopping and he was panting on the floor. A thread of foul spit dripped from his mouth. His nose was running, his face was smeared with dust and froth.

I nudged him a bit with the toe of my shoe.

“Well then, Don Juan, how are we?”

I felt as fierce as life. He gave me a completely vacant look. I made my way round him the way you make your way round a piece of rubbish that turns your stomach, and went out to breathe the mild provincial air. I damn well needed to, I can tell you!

4

If my alibi was to be credible, I couldn’t very well return to the Castains’ before the next day. So I strolled around Pont-de-l’Air until the evening, having lunch in a country bistro, sauntering along a canal, reading newspapers which had no interest for me. Germaine had entrusted me with a nasty job, and I felt slightly resentful towards her. The one thing that cheered me up was thinking of Thuillier’s face when he developed his photos. When he saw himself he wouldn’t believe his eyes. That would give the damn show-off a shock! My own cruelty surprised me, because by and large I’m quite a nice guy. Only I was smitten with Germaine and could not accept her weakness with Maurice.

That empty day seemed never-ending, so I was very glad to return to the fold. The Hôtel de la Gare felt almost like a safe haven to me. I no longer had any desire to leave my position; it had a seductive side to it.

The next morning, very early, I went to retrieve my cases from the station. They had arrived the previous day. Next I changed my clothes, as my underwear really wasn’t too fresh. In a white shirt, dressed in a navy-blue suit and with a black tie—as befits a gentleman who makes a living from grief—I presented myself at the Castains’.

The shop wasn’t yet open and I had to knock on the wooden shutter. Light-footed Achille came to let me in, wearing a grey brushed-cotton waistcoat and comfortable fur-lined slippers.

“You already!” he exclaimed.

“Yes, am I too early?”

“That’s not a bad thing! You can have some coffee with me.”

I went into the hideous little shop which smelt of dead people. We made our way through to the dining room, where Germaine was laying out bowls for breakfast. She had her hair tied up in a ribbon and was wearing a big red dressing gown.

I looked at her and a warm caress ran through my body. She looked at me too…

“Good trip?” Castain asked.

“Excellent, if a bit brief.”

He gave an ugly little laugh.

“Do you know?”

“What?”

And he suddenly went quiet, then, almost simpering but seeming more embarrassed than anything:

“I’d got it into my head that you wouldn’t come back.”

I looked at him: “The very idea!”

“I had. I thought the work wasn’t to your taste. Obviously it’s off-putting at the start. But you’ll see, you get used to it very quickly and very well. Like every trade, when you practise it diligently you begin to love it.”

He was touching. I felt I meant something to him. I’d impressed him with my casual ways, my direct manner and my well-cut suits.

“Well, as you see, I’m here. Ready to get stuck in. Speaking of which, are there any new deaths in the neighbourhood?”

“Yes, a butcher’s wife. We’re going to try an experiment.”

“What kind of experiment?”

“You’ll go on your own to offer our services. Anyway, I’m busy with the Richard funeral this morning.”

He turned to Germaine.

“And you, do me the pleasure of getting dressed, eh? I’ll be leaving in ten minutes and I don’t want to see you in the shop in your dressing gown!”

She nodded in agreement.

“Right, I’ll dress first.”

“Look, Delange, you’ll wait until my wife is dressed before you leave. I’ve put the butcher’s address on my desk ready for you—it’s less than a hundred metres away.”

He swallowed his bowl of coffee while I carefully buttered my biscottes. I was delighted by the thought of remaining alone with Germaine for a moment; that was unhoped for! She seemed content with the unforeseen blessing as well, but for different reasons. She was thinking I would be able to give her an account of my “mission” in detail. Although not a muscle in her face moved, I could see from the way her fingers were trembling that she was all keyed up.

I avoided looking at her during the time it took for Castain to get ready. When he came out of his room, dressed in a black uniform and a cocked hat, I just burst out laughing. He looked like a Walt Disney character: he was exactly like a gnome in disguise.

“Are you making fun of me?”

“No, but it’s just so funny for me to see you in that get-up. Don’t you feel—I don’t know—comical?”

“Not at all!”