Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

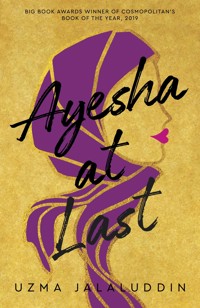

Winner of the Hearst Big Books Award - Cosmopolitan's Book of the Year A Mirror 'Best Books to Read This Summer' pick 'A clever homage to Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice that you'll love, even if you never got round to reading the original.' Cosmopolitan Ayesha Shamsi has a lot going on. Her dreams of being a poet have been overtaken by a demanding teaching job. Her boisterous Muslim family, and numerous (interfering) aunties, are professional naggers. And her flighty young cousin, about to reject her one hundredth marriage proposal, is a constant reminder that Ayesha is still single. Ayesha might be a little lonely, but the one thing she doesn't want is an arranged marriage. And then she meets Khalid... How could a man so conservative and judgmental (and, yes, smart and annoyingly handsome) have wormed his way into her thoughts so quickly? As for Khalid, he's happy the way he is; his mother will find him a suitable bride. But why can't he get the captivating, outspoken Ayesha out of his mind? They're far too different to be a good match, surely... Readers love AYESHA AT LAST 'Couldn't put the book down' ***** 'An entertaining read with laughter and tears' ***** 'I read this book in a day and loved it!' ***** 'A hilarious and charming love story' ***** 'Perfect book for holiday reading' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 492

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Uzma Jalaluddin attended the University of Toronto for her undergraduate and teacher’s college, where she spent too much time perusing the library stacks for novels to read, and not enough time poring over textbooks. She grew up in a close knit, diverse neighbourhood in Toronto, Canada, and regularly attended events at her local mosque, even when her parents didn’t make her. Today she teaches in a public high school, and writes ‘Samosas and Maple Syrup,’ a parenting and culture column for the Toronto Star, Canada’s largest daily newspaper. All of her reading and secret novel writing eventually paid off . . . Ayesha At Last is her first novel. She lives with her husband and two sons near Toronto.

@Uzma Writes

First published in Canada in 2018 by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, Toronto, Canada.

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Uzma Jalaluddin, 2018

The moral right of Uzma Jalaluddin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 794 9 Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 690 4 E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 691 1

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For Imtiaz, who said “when,” not “if”

CHAPTER ONE

He wondered if he would see her today.

Khalid Mirza sat at the breakfast bar of his light-filled kitchen, long legs almost reaching the floor. It was seven in the morning, and his eyes were trained on the window, the one with the best view of the townhouse complex across the street.

His patience was rewarded.

A young woman wearing a purple hijab, blue button-down shirt, blazer and black pants ran down the steps of the middle townhouse, balancing a red ceramic travel mug and canvas satchel. She stumbled but caught herself, skidding to a stop in front of an aging sedan. She put the mug on the hood of the car and unlocked the door.

Khalid had seen her several times since he had moved into the neighbourhood two months ago, always with her red ceramic mug, always in a hurry. She was a petite woman with a round face and dreamy smile, skin a golden burnished copper that glowed in the sullen March morning.

It is not appropriate to stare at women, no matter how interesting their purple hijabs, Khalid reminded himself.

Yet his eyes returned for a second, wistful look. She was so beautiful.

The sound of Bollywood music blaring from a car speaker made the young woman freeze. She peered around her Toyota Corolla to see a red Mercedes SLK convertible zoom into her driveway. Khalid watched as the young woman dropped to a crouch behind her car. Who was she hiding from? He leaned forward for a better look.

“What are you looking at, Khalid?” asked his mother, Farzana.

“Nothing, Ammi,” Khalid said, and took a bite of the clammy scrambled eggs Farzana had prepared for breakfast. When he looked up again, the young woman and her canvas satchel were inside the Toyota.

Her red travel mug was not.

It flew off the roof of her car as she sped away, smashing into a hundred pieces and narrowly missing the red Mercedes.

Khalid laughed out loud. When he looked up, he caught his mother’s stern gaze.

“It’s such a lovely day outside,” Farzana said, giving her son a hard look. “I can see why your eyes are drawn to the view.”

Khalid flushed at her words. Ammi had been dropping hints lately. She thought it was time for him to marry. He had a steady job, and twenty-six was a good age to settle down. Their family was wealthy and could easily pay for the large wedding his mother wanted.

“I was going to tell you after I’d made a few choices, but it appears you are ready to hear the news. I have begun the search for your wife,” Farzana announced, and her tone brooked no opposition. “Love comes after marriage, not before. These Western ideas of romantic love are utter nonsense. Just look at the American divorce rate.”

Khalid paused mid-bite, but his mother didn’t notice. Her announcement was surprising, but the news was not unexpected or even unwelcome. He resumed eating.

“I will find you the perfect wife—modest, not too educated. If we can’t find someone local, we will search for a girl back home.”

“Back home” for Farzana was Hyderabad, India, though she had lived in Canada for over thirty years. Khalid had been born in a suburb west of Toronto and lived there for most of his life until his father’s death six months ago, before Farzana and Khalid had moved to the east end of the city. Farzana had insisted on the move, and though Khalid had been sorry to leave his friends and the mosque he had frequented with his father, deep down he thought it might do them both some good.

Their new neighbourhood had felt instantly comfortable. From the moment they’d arrived, Khalid felt as if he had finally come home. There were more cars parked three or four deep on extended driveways, more untamed backyards in need of the maintenance that only time, money and access to professional services could provide. Yet the people were kind, friendly even, and Khalid was at ease among the brown and black faces that reflected his own.

Farzana neatly flipped another paratha flatbread onto her son’s plate, though he had not asked for more. “The wedding will be in July. Everyone will want an invitation, but I will limit the guest list to six hundred people. Any more is showing off.”

Humming to herself, she placed a small pot on the stove, adding water, milk, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom and tea leaves for chai. Khalid’s eyes lingered on the chipped forest-green mug on the counter. His father’s mug. Ammi had used that mug for his Abba’s chai for years. This was the first time he had seen it out of the cupboard since the move. Maybe his mother was finally beginning to make her way through the cloud of grief that had paralyzed her after Abba’s death.

There was so much of the past they did not talk about. Khalid was relieved she was thinking about the future. Or rather, his future.

The idea of an arranged marriage had never bothered Khalid. A partner carefully chosen for him, just as his parents had been chosen for each other and their parents before them, seemed like a tidy practice. He liked the idea of being part of an unbroken chain that honoured tradition and ensured family peace and stability. He knew that some people, even his own sister, thought the practice of arranged marriage was restrictive, but he found it comforting. Romantic relationships and their accompanying perks were for marriage only.

At the thought of romantic perks, Khalid’s attention drifted to the window once more—but he stopped himself. The girl with the (broken) red mug would never be more than a fantasy. Because while it is a truth universally acknowledged that a single Muslim man must be in want of a wife, there’s an even greater truth: To his Indian mother, his own inclinations are of secondary importance.

CHAPTER TWO

The Toyota lurched down the street, wheezing and anemic. Ayesha reached for her travel mug, but her hand closed on empty air. In the rear-view mirror she spotted the red shards on the asphalt. Blast.

She had been in such a hurry to get away from Hafsa. Now she would have to face her first day as a substitute high school teacher without the comforting armour of chai.

No matter, it was worth it. The moment she had spotted the red Mercedes convertible pulling onto the street, Ayesha had known why her cousin was visiting so early in the morning, and she didn’t want to hear it.

Besides, there was one rule repeatedly drilled into her at teachers’ college: A teacher can never, under any circumstances, be late.

Ayesha had graduated from teachers’ college last June. It had taken nearly seven months of papering local schools with her resumé to secure a substitute teaching position. Now her stomach flipped over as she parked in the staff lot of Brookridge High School, a squat, two-storey brown brick building constructed in the 1970s, ugly and functional.

The building was similar in layout and atmosphere to her old high school. It had the same well-tended shabbiness of a public building, the same blue-tinted fluorescent lighting, and waxed and speckled linoleum floors. The same mostly white staff dressed in business-formal slacks and skirts, the same mostly brown and black students slouching in jeans, track pants and too-short dresses. Ayesha tugged self-consciously at her carefully chosen teacher clothes: blue button-down shirt and serviceable black pants. Her hands nervously smoothed the top of her purple hijab.

Part of both worlds, yet part of neither, she thought.

Such existential thoughts were really not helping to settle the butterflies in her stomach.

She entered the large, open foyer, its concrete walls painted a dull green and smelling faintly of industrial cleaning solvent. The familiar scent calmed her, and she smiled slightly at a female student in black leggings and a blue hoodie, carrying an overloaded backpack. The girl gave her a dubious look before shifting her bag and walking purposely down the hall, reminding Ayesha to hurry. A teacher must never be late.

The secretary, Mary, was waiting for her in the main office with forms to sign. The principal, Mr. Evorem, was absent today, Mary explained. “He’ll want to meet you tomorrow to welcome you properly.”

A white man in his early thirties with a short black beard walked into the office just as she was finishing the paperwork, and Mary asked him to take Ayesha to her class. He peered over her shoulder at her schedule.

“Grade ten science?” His eyes were wide. “You’re covering for Rudy?”

“Who’s Rudy?” Ayesha asked as they walked toward the stairs.

“He’s the last teacher those little shits scared off. I think he chose early retirement over that class.”

Ayesha looked at him, waiting for the punchline. There wasn’t one. “Nobody told me that.”

“I hope you’re light on your feet. The bastards like to throw things.”

FORTY minutes later, Ayesha crouched on the toilet in the staff bathroom, bookended by feelings of self-pity and guilt. Instead of teaching, she was hiding from her class. Even worse, she was writing a poem in her purple spiral notebook.

I can’t do this.

This thing that I should do.

I can do this.

This thing I don’t want to do.

I want to be away, weaving words of truth.

Not here, trapped between desk and freedom and family.

She should be teaching, not writing. She had vowed to leave this part of her behind when she’d left for work that morning. Instead, she hadn’t been able to resist placing the purple spiral notebook in her bag, like a child’s security blanket. She gripped her pen tightly and tried not to stare at her cell phone.

“Come on, Clara,” she said out loud. Then she held her breath, hoping no one had heard. But of course they hadn’t. This was the staff bathroom, and it was the middle of the school day. The other teachers were teaching, not hiding and writing poetry.

She squinted at the page, rereading her words. Correction: writing bad poetry.

Her phone beeped: a text message from her best friend, Clara.

What do you mean you can’t do this? You just got there.

Ayesha texted back.

My class hates me. They were throwing things at each other, and they didn’t listen to a word I said. Can you call the school and tell them there’s an emergency at home?

Her phone rang.

“You picked the wrong profession.” Clara’s voice was low.

“I’ll come back to teach tomorrow, when I’m ready,” Ayesha said.

“Babe, you are never going to be ready to teach. You know what you’re ready for? Writing poems. Exploring the world. Falling in love. Remember?” Ayesha pictured Clara in front of her—blue eyes wide with concern, fingers fiddling with strawberry blond hair. “I bet you’re writing a poem about this right now. Aren’t you?” Her friend’s voice was accusing and impatient. They had had variations of this same conversation so many times, Ayesha couldn’t blame Clara for being sick of it. She was sick of it herself.

Her eyes flicked to the notebook, and she shut it firmly. No more. “Poetry is for paupers. I’m not Hafsa. I don’t have a rich father to pay my bills, and I promised Sulaiman Mamu I would pay him back for tuition.”

She remained silent about the other two items—exploring the world, falling in love—the first as impossible as the second. She had no money, and falling in love would be difficult when she had never even held someone’s hand before. “Hafsa is getting married this summer,” Ayesha said instead. “She came over this morning to tell me, but I already knew. Nani and Samira Aunty have been talking about her rishtas for weeks.”

Clara, an only child, loved hearing about Ayesha’s large extended family. She was particularly intrigued by the traditional rishta proposal process, which Ayesha had explained in hilarious detail. Prospective partners were introduced to each other after being carefully vetted by parents and family. Ayesha had received a few rishta proposals herself, years ago, though they had never led to a wedding. She hadn’t really connected with any of the potential suitors, and they must have felt likewise because she’d never heard from them after the initial meetings.

“Hafsa can’t get married! She’s a baby!” Clara exclaimed.

Ayesha started laughing. “She’s got the entire wedding planned already. All she needs is the groom.”

“Your cousin is crazy. You’re the one who should be getting married. Or me. Rob still flinches whenever I mention weddings, after ten years together.”

Ayesha was starting to regret this topic of conversation. “If Hafsa wants to get married, I’m happy for her,” she said. She imagined twenty-year-old Hafsa reclining on an ornate chaise as she surveyed a parade of handsome, wealthy men. She pictured her cousin languidly pointing to one man at random, and just like that, the marriage would be arranged.

So easy, so simple, to find the one person who would cherish and protect your heart forever. Everything came easy for Hafsa.

Clara pressed her point. “When do you get to be happy? When was the last time you went on a date, or finished and performed a poem?” Clara thought Ayesha was afraid of love because of what had happened to her father and afraid to dream because of her family’s expectations.

Ayesha disagreed. “My family is counting on me to set a good example for Hafsa. I’m the eldest kid in the family. I want to set the bar high for everyone else. I can’t let Mom, Sulaiman Mamu or Nana down, not after everything they’ve done for me. All that other stuff can wait.”

Clara sighed. “Why don’t you come to Bella’s tonight?”

A long time ago, a different Ayesha had performed poetry at Bella’s lounge. Another reminder of the road not taken. She smothered a laugh that sounded like a sob.

“Ash, you got this,” Clara said, her voice softening. “Do all that teacher stuff. Send the troublemakers to the office. Make a seating chart. Stop hiding in the bathroom.”

There was a discreet knock on the stall door, and Ayesha ended the call with Clara.

“Miss Shamsi?” Mary said, sounding awkward. “Your class said you might be in here.”

They’re not my class, Ayesha thought. They need a circus trainer, not a teacher. She flushed, wiped sweaty palms on her pants and tucked the purple notebook back inside her bag. Mary stood outside, a look of pity on her face.

“There was an emergency, but I’m better now,” Ayesha said with dignity. “When does the class end?”

“You still have another forty minutes, honey.” Mary patted her on the shoulder. “I’ll send an assistant to help with your first class. She’ll keep an eye on them when your back is turned. Oh, and I forgot to give this to you earlier.”

Mary handed Ayesha an ID badge with STAFF written in bold letters at the top.

Ayesha stared at the official-looking badge. This was why she had attended teachers’ college, why she had worked so hard at her in-school placements. Her mother and grandparents had left behind so much when they immigrated to Canada. She wanted their sacrifice to mean something.

There was no turning back, not now.

Her thoughts drifted to the purple notebook in her bag. Maybe if she worked on the poem tonight, she could perform it at Bella’s sometime . . .

But no. All of that lay behind her. It was time to focus on the road in front.

“Everyone starts out right here. You’ll get the hang of it,” Mary said.

Mary meant to be kind, but Ayesha knew that not everyone started from the same place. Some people were always a little ahead. Or in her case, constantly playing catch-up.

The rest of the day was not as dramatic as the morning, yet Ayesha felt deflated when she drove home after school. Teaching was not what she’d expected and nothing like her training, where she’d had the comforting guidance of a mentor teacher. The entire experience had been nerve-racking, and she had felt perpetually caught in the bored tractor-beam stares of twenty-eight teenagers.

All she wanted now was to go home, drink a cup of very strong chai and reconsider her life choices.

She turned onto her street and spied a red Mercedes parked in the driveway.

Hafsa was back, and this time there was no escape.

CHAPTER THREE

Khalid kept his head down as he walked through the narrow back hallway of Livetech Solutions, his employer for the past five years. He was dressed in his usual work attire—fullsleeved white robe that skimmed his ankles, black dress pants, white skullcap jammed over dark brown hair that curled over his ears. His beard was long and luxuriously thick, contrasting sharply with his pale olive complexion.

He was a large man, tall and broad, and the corridor was narrow. He looked up to see his co-worker Clara standing in the middle of the hallway, whispering into her cell phone. Khalid did not wish to disturb what appeared to be an intense conversation; he also did not wish to brush past her in the hallway. He had been raised to believe that non-related men and women should never get too close—socially, emotionally and especially physically.

“When an unmarried man and woman are alone together, a third person is present: Satan,” Ammi often told him. Khalid found this reminder helpful, especially when paired with cold showers. There wasn’t much more that a twenty-six-year-old virgin-by-choice could do, really.

He didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but Clara had raised her voice. “When do you get to be happy?” she said sharply into her phone.

Khalid blinked at the question, which so neatly mirrored his own thoughts.

His cell phone dinged with a new email, and he opened it, grateful for the distraction. His heart sank when he read the subject line and recognized the sender: his sister, Zareena. He hadn’t told her about their move. He hadn’t been sure how she would react to the sale of their childhood home. It looked like some other busybody had thoughtfully informed her instead. He began to read.

Re: the last to know?

Khalid,

I can’t believe I had to hear the news from my father-in-law. You sold the house and moved? I loved that house. It was so easy to sneak out of my bedroom. But I guess it was too hard after Abba died.

Guess what? I got bored and started volunteering my time for a Cause. You would be so proud of me. I’m teaching English to a class of little girls at the local school. My students are super sweet. Their parents can barely afford to send them to class. Half the time they show up with no lunches, but their clothes are so tidy, their hair in neat braids, and they want to learn so badly. Not like when I was in school! They always bring me a flower or a fruit they stole from someone’s garden. I sneak them rice and dal sometimes.

—Zareena

P.S. Maple donuts and Tim Hortons hot chocolate.

P.P.S. Thanks for the gift. Can you use Western Union next time plz? It’s closer and you know how I hate to walk.

Zareena’s emails and texts arrived every few days and reported on her daily life. Sometimes she complained about the dullness of her days, or which of her dozens of in-laws were irritating her. Sometimes she asked him about work, or if he had talked to a girl yet . . . or even made eye contact with one.

The one thing she never asked about was their mother. The second thing she never discussed was her husband.

The postscript was always something Zareena missed about Canada. Her words brought the taste of maple dip donuts and toosweet hot chocolate to his lips. Their father, Faheem, used to treat them on the way back from Sunday morning Islamic school when they were kids. Before Zareena went away.

After she left, whenever Khalid mentioned her name, his father would freeze and Ammi would become upset. Soon her name became an unspoken word in their home.

Clara’s call had ended, and he noticed her examining him as he read his email. They knew each other, but had never spoken. He wondered if she was uncomfortable with the way he dressed. Some people found his robes and skullcap difficult to reconcile with an office environment. But Khalid had long ago decided to be honest about who he was: an observant Muslim man who walked with faith both outwardly and inwardly, just as some of his Muslim sisters did by wearing the hijab.

Still, sometimes it made people nervous. Though Clara did not seem wary. She appeared almost . . . appraising.

Which made him nervous.

Khalid motioned in front of him. “After you,” he said politely.

Clara didn’t move. “My friend is having a crisis. Her first day at a new job.”

“That can be difficult,” Khalid said, looking directly at her.

Now she looked curious. About him? Women were never curious about him.

“It’s sort of my first day too,” Clara said, leaning close. “I was promoted to regional manager of Human Resources.”

“Congratulations.” Khalid inclined his head in acknowledgement. “I know you will fulfill your duties with integrity.”

“My boyfriend, Rob, is happy about the pay raise,” Clara said with a smile. “I’m reporting to Sheila Watts. Do you know her?”

Khalid shook his head. Sheila had replaced his old director a few weeks ago, but he had yet to meet his first female boss.

The door behind Clara opened and a petite woman with black hair and blue eyes stepped out. She was shorter than Clara, dressed in a sleeveless top and tight black pencil skirt. Above her right breast was pinned a large crystal brooch in the shape of a spider, its winking red eyes matching her lipstick.

Clara stepped forward with a friendly smile.

“Sheila, I wanted to introduce myself—I’m Clara Taylor. John promoted me just before he left the company.”

Sheila looked at the outstretched hand and beaming face before her. A faint expression of distaste lurked at her lips and she briefly shook Clara’s hand, using only the very tips of her fingers.

Khalid knew what was coming next, and he felt powerless to stop it. Usually when he was introduced to female clients and co-workers, he had time to prepare beforehand with a carefully worded email about his no-touch rule.

As the women talked, he subtly edged away from their conversation, taking tiny steps down the hall. But it was no use; Clara’s friendliness foiled his escape.

“Sheila, this is our e-commerce project manager, Khalid Mirza,” she said, and both women turned to him.

A hard glance from Sheila took in Khalid’s white robe and skullcap. Her eyes lingered on his long beard.

Her gaze was the opposite of appraising, Khalid thought. She looked annoyed.

Then everything went from bad to worse. Sheila leaned forward and stuck out her hand for him to shake.

They stared at each other.

“I’m sorry, I don’t shake hands with women. It’s against my religion,” he blurted.

Sheila left her hand outstretched for another moment, cold eyes locked on his face. Then she slowly pulled back and raised an eyebrow. “I should have assumed as much from your clothing. Tell me, Khalid: Where are you from?”

“Toronto,” Khalid answered. His face flamed beneath his thick beard; he didn’t know where to look.

“No,” Sheila laughed lightly. “I mean where are you from originally?”

“Toronto,” Khalid responded again, and this time his voice was resigned.

Clara shifted, looking tense and uncomfortable. “I’m originally from Newfoundland,” she said brightly.

“I lived in the Middle East for a while,” Sheila said to Khalid, her voice low and pleasant. “Saudi Arabia. I found it so interesting that the women wore black while the men wore white. There’s something symbolic about that, isn’t there? Half the population in shadow while the rest live in light. You must be so grateful to live in a country that welcomes everybody.” Sheila’s laughter sounded high and artificial. “Of course, when I was in Saudi Arabia, I wasn’t afforded the same courtesy.”

Khalid’s eyes were lowered to the ground, his head bowed. “I apologize, Ms. Watts. I meant no disrespect,” he said finally. “Please forgive me.” He turned around and walked back the way he had come, hands trembling.

He took the long way around the floor and caught the service elevator down to his small office in the basement. It was sparsely furnished with two grey metal desks squeezed together, a black bookcase wedged behind the door and a sagging blue couch against the back wall. Rumour had it this office used to be a maintenance closet, but he was grateful for the privacy, especially when he prayed in the afternoon.

It was nine thirty in the morning, earlier than usual for Amir to already be at his desk. Though judging by the rumpled suit, his co-worker had spent last night at the office. Again.

“Assalamu Alaikum, Amir. I thought we talked about this.” Khalid hid his shaking hands by folding his arms.

“My date wasn’t exactly interested in a sleepover, if you know what I mean. Bitches, am I right?” Amir reached for a water bottle on his desk, opened it and began chugging rapidly.

Khalid winced at his description. “I can’t keep covering for you.”

Amir had been hired the previous year as part of Livetech’s “Welcome Wagon” program for immigrants. Technically, Khalid was his manager. Most days he felt like a babysitter.

“Last time, I swear. This would never happen if you came out with me and stopped me from committing my many sins. I promise I’ll introduce you to some pretty girls.”

Khalid was tempted to confess Ammi’s plans to find him a wife, but instead he stuck to his usual line. “Out of respect for my future wife, I don’t believe in sleeping around before marriage.”

Amir only laughed. “Classic Khalid. I tell my friends about you all the time. They don’t believe half my stories. All the other Muslim guys I know scrub up for Friday prayers just like you, but they know how to have fun.”

Khalid ignored him and settled down to check emails; the most recent was from Sheila, sent only moments ago.

Khalid, I’m glad we met today. I’d like to begin our working relationship with a performance review. I look forward to a frank discussion of your strengths and many areas of improvement. The meeting is scheduled for Monday at 3 p.m. I trust this appointment will not interfere with any religious obligations.

Amir, noticing Khalid’s concerned expression, got up to read over his shoulder. He whistled. “What did you do?”

Khalid shrugged. “I declined to shake her hand.”

“K-Man, you need to edit. Figure out what works for you, throw out what doesn’t. It’s not like we’re still riding around on camels, right?”

“I’m not sure what you mean.”

Amir punched Khalid lightly on his arm. “You’re too old to be this naive. Watch your back, brother.”

Khalid kept silent. He knew how Amir saw him—as an anachronistic throwback, a walking target for ridicule.

Sometimes he wished he were different. But even if Khalid “edited” everything about himself—his clothes, his beard, his words—it wouldn’t erase the loneliness he felt every day. The loneliness he had felt ever since his sister left home almost twelve years ago.

His white robes and beard were a comfortable security blanket, his way of communicating without saying a word. Even though he knew there were other, easier ways to be, Khalid had chosen the one that felt the most authentic to him, and he had no plans to waver.

Besides, the robes provided great air circulation.

And everything happened by the will of Allah.

CHAPTER FOUR

Sheila had an entire wall of windows in her office, Clara noted. Her new boss sat at a large black desk so shiny it reflected her perfectly poised image. She was typing an email, and she looked angry, her red nails stabbing the keyboard. Clara was seated on a lethal-looking chair; the curlicued metal embellishments on the back felt like they had been filed to a knife’s edge.

Sheila sent her email and then stared at Clara for a moment before leaning forward with a confidential air. “Five years ago, I was in customer support, and now look at me.” She spread out her arms to encompass the large, airy office. “Hard work, that’s the key. And it doesn’t hurt to look good doing it.” Her tight smile revealed tiny white teeth.

Clara shifted uneasily. The scene outside with Khalid was still fresh in her mind. As the new regional manager of Human Resources, she felt responsible.

Sheila straightened in her chair. “People are intimidated by a woman in power, Clara. They think it goes against the natural order of things. But the world is changing, and it’s important that we embrace the transformation. You grew up in Newfoundland.”

Clara blinked, head spinning at Sheila’s abrupt topic change. So her new boss hadn’t been simply ignoring her outside in the hallway.

There had been rumours about Sheila Watts. When Clara was first promoted, her co-workers had warned her about the new boss.

“They call Sheila ‘the Shark’ because she always circles her prey before she attacks,” one remarked. Clara didn’t take gossip seriously, but now she was worried.

If only Khalid had shaken Sheila’s hand, things would have been so much easier. Her friend Ayesha had no problem shaking people’s hands, and she was Muslim. But this was HR 101: Everyone was entitled to their own interpretation of faith, even if it did make her job especially challenging. Also, her new boss’s repetition of that question—Where are you from?—hadn’t sat well with her. If Khalid had been awkward, Sheila’s reaction had been no less so, though Clara doubted her new boss would see things that way.

Ayesha thought she had it bad standing in front of bored teenagers. Finding a way through the tricky waters that made up people’s backgrounds and beliefs was even worse. She reined in her thoughts and focused on Sheila’s words.

“We’re fortunate at Livetech to employ people from all over the world. Diversity is essential in today’s global marketplace, but it can also present unique challenges,” Sheila said.

“I grew up in a diverse neighbourhood, so I’m used to living and working with people of different ethnicities and cultures,” Clara said.

Sheila waved her words aside. “I’m going to let you in on a secret, Clara. Livetech Solutions is ready to join the global technology stage with our new product launch, but there are bad apples polluting the orchard. That’s where you come in.”

Clara’s laptop was open now, and she was taking notes. Polluting the orchard. Bad apples. Her fingers hesitated over the keyboard. “Are you asking me to fire someone?” she said, not quite masking the squeak of terror in her voice. “So far my HR work at Livetech has focused on mediation, conflict resolution and mental health initiatives.”

“Termination is a last resort, and proper protocols must be followed. We wouldn’t want Livetech to be involved in any legal unpleasantness.” Sheila gave Clara an arch look. “Let’s start with Khalid Mirza. I want you to prepare a file on his work habits, how often he misses deadlines and his inappropriate behaviour toward women.”

Clara was typing furiously but slowed down at Sheila’s words. “Is this about what happened in the hallway earlier?”

Sheila lowered her voice. “You saw what he did,” she said. “He’s clearly one of those extremist Moslems.”

Clara leaned back, fighting to appear calm. The chair pinched her shoulder and she winced. “I’m not sure what you mean.”

Sheila’s tinkling laugh rang out. “You are so innocent. I love working with a blank slate.”

Clara’s sense of unease grew.

“I was headhunted by a big conglomerate in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia, a few years ago. I lasted six months.” Sheila’s teeth gleamed. “Khalid would fit in with my former employers perfectly, right down to the bedsheets and dirty beard.”

Clara’s stomach clenched. “You can’t get rid of someone because of their religious beliefs,” she said carefully. “And his beard looks presentable to me. He told me he dry cleans his robes every week.”

Sheila’s eyes narrowed. “Livetech is a growing global player. Our senior team must maintain a certain professionalism, and that includes a uniformity of dress.” She leaned across the desk. “Sweetheart, you’ll find this type of behaviour the higher you climb. Men afraid of a woman with power, men who can’t handle a woman’s ambition. There are limits to religious accommodation—and it’s your job to find those limits. I’ve set up a meeting with Khalid for next week, which is more than enough time for you to compile your report. I do hope your promotion was the right decision for Livetech.”

When Clara left the office, she felt uneasy. She thought about Ayesha and her family, who had embraced her when her own parents had moved back to Newfoundland during freshman year. They prayed five times a day and wore “funny” clothing too.

Khalid might have chosen to follow his faith in a way that appeared conservative, but that didn’t mean he deserved to be fired. By all accounts he was respectful and hard working, if a little quiet. How could Clara, in good conscience, allow this to happen? She’d gone into human resources to advocate for people, not to promote inequity.

Yet Sheila had made it very clear that her job was on the line. Clara had been so proud of her promotion, so excited to begin climbing the corporate ladder. But already her new role was turning out to be more difficult than she had imagined.

There had to be a way out of this.

An idea popped into her head. Perhaps there was a way she could help Khalid, and Ayesha too. Her friend needed to have some fun, and her co-worker needed to loosen up and learn how to talk to women. Besides, Sheila had asked her to investigate Khalid, not fire him. As the new regional manager of Human Resources, she had the responsibility of seeing both sides of any workplace issue.

Clara took the elevator to the basement. Standing on the threshold of Khalid’s shared office, she tried to see him the way Sheila did, as a dangerous, sexist outsider. But he looked like the other Muslim men in the neighbourhood where she’d grown up, like Ayesha’s grandfather dressed for Friday prayers. She knocked on the door and entered the office.

“It was so nice bumping into you in the hall today, Khalid,” she said.

He looked up from the screen, surprised. “How was your meeting with Sheila?”

The less said about that, the better. “Do you enjoy listening to poetry?” Clara asked instead.

Khalid considered this, puzzled. “I read the Quran. It is a very poetic book.”

Amir snickered. Khalid’s obnoxious office mate stared at her, eyes on her breasts. She ignored him.

“Have you heard of Bella’s? They’re having an open mike poetry night on the weekend. I’d love it if you joined me and my friend.”

Khalid looked uncomfortable. “I do not think that would appropriate—” he began, but Clara cut him off.

“I’m launching an initiative at Livetech that I hope will be of interest to you. I want to organize a workshop on diversity and religious accommodation. I could really use your input.”

Still Khalid hesitated.

“Come on, K-Man,” Amir said. “It will be fun. I’ll bring my boys.”

“Is Bella’s a bar?” Khalid asked. “Will there be alcohol?”

Clara shook her head, fingers crossed behind her back. “It’s a lounge, not a bar. I really appreciate this. In return, maybe I can offer you a few suggestions for your meeting with Sheila next week.”

She left before Khalid could ask how she knew about his meeting, or the difference between a bar and a lounge. Or who her friend was.

Clara smiled to herself. Khalid Mirza, have I got a girl for you.

CHAPTER FIVE

Ayesha parked her car in the driveway and slowly removed her key from the ignition. It was six o’clock, and she had survived her first week as a substitute high school teacher. Barely.

In the bag beside her were two books on classroom management strategies, along with the tenth-grade science curriculum. All of which would eat up her entire weekend.

But not tonight. Tonight she was going to party like she was still an undergrad. Which meant takeout pizza and old Bollywood movies.

What time should I come over? Ayesha texted Hafsa.

Whatever. It’s not like you have time for me anymore, career-lady.

Ayesha sighed. Hafsa was upset because she hadn’t responded to her texts or phone calls all week. Because I have a job, because I can’t skip work to go for a facial, she thought, and then she felt guilty. Hafsa was like a baby sister, and sometimes baby sisters threw tantrums. The best way to deal with a temper tantrum was to ignore it. She quickly texted Hafsa again:

I always have time for Bollywood Night! Come on, we are going to have FUN! :) We need to celebrate your husband search! I’ll be there in an hour.

Ayesha knew she shouldn’t dawdle in the car. The “Bored Aunty Brigade,” as she had nicknamed her gossipy desi neighbours, were likely peering through their windows right now.

Ayesha Shamsi took her sweet time going inside, she imagined them saying. Up to no good. No husband yet. Who will marry her now? Cluck, cluck, cluck.

She flung open the car door, fake smile plastered to her face. Let them stare. She was too old to care what the Aunty Brigade thought of her!

“‘Oh, she doth teach the torches to burn bright,’” a soft voice called from the front lawn. “‘Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear. So shows a snowy dove trooping with crows. As yonder lady o’er her fellows shows.’”

“Nana, are you smoking again?” Ayesha’s frozen smile thawed into a more natural one as she surveyed her grandfather on his favourite green plastic lawn chair, hiding behind their lone scraggly maple tree. Ayesha’s grandfather was a retired English professor from Osmania University in Hyderabad, India. He had a soft spot for the Bard, and quoted him often.

“No,” he said, blowing cigarette smoke thoughtfully into the emaciated branches, which were just starting to turn green. Spring in the city arrived slowly, a lazy cat stretching after a long winter nap. “This is just an illusion, as is most of reality. This is not a cigarette. I am not hiding from Nani and waiting for you. And you are not working too hard. We are all just cosmic players in the eternal dance of life.”

“Nana, you talk too much bakwas.” Ayesha carefully removed the cigarette from her grandfather’s unresisting fingers and kissed him gently on the cheek. “You’re not even wearing a jacket. It’s cold.”

“I am a Canadian. I feel no cold.” But he got up gingerly from the lawn chair and followed her into the house.

“Smoking is bad for you. It causes lung cancer and emphysema. It is also very unfashionable. You said you quit during Ramadan,” Ayesha scolded as they entered the house and stood in the tiny entranceway to remove their shoes.

“I always quit during Ramadan. I restart after Eid. And I do not care if it is unfashionable. I am a nonconformist.”

Ayesha hid her smile and held her hand out. After a slight hesitation, he placed a half-empty pack of cigarettes in her palm.

“Who’s your supplier?” Ayesha asked as she pocketed the package.

“I’ll never talk.” He smiled rakishly at her. “If it truly disturbs you, I promise to stop. Just as soon as you promise to quit your job. Nice girls from good families shouldn’t work outside the home.” He twinkled at her.

“Nana, you’re so sexist,” Ayesha said. “Who said I’m a nice girl?”

“Beti, you are the nicest.”

When Ayesha, her mother Saleha, her brother Idris and her grandparents had first immigrated to Canada seventeen years ago, they had felt unmoored in their adopted home and by her father’s sudden, violent death in India. Saleha was in mourning, Idris was an infant. Her grandparents had stepped in, caring for Ayesha and Idris while their mother grieved. Ayesha grew especially close to Nana, who had read to her every night. She joked that she had learned to speak “Shakespearean” English before “Canadian” English.

Ayesha and Nana walked into the kitchen of the three-storey townhouse. Ayesha’s mother had use of the third-floor loft, while the two bedrooms on the second floor were occupied by Ayesha and her seventeen-year-old brother. The small kitchen and family room were shared, and her grandparents had the basement suite.

Their home was located in the east end of the city, in a suburb named Scarborough. The neighbourhood consisted of mixed housing, their aging townhouse-condominium complex set among single homes with large backyards and double-car garages, as well as smaller semi-detached units. Driveways modified to accommodate three or four vehicles were common, with luxury brands like Mercedes and BMW sprinkled among older, more affordable types. Minivans dotted most driveways, and many garages were furnished with sofas and TV screens and used as additional gathering spaces for family and friends. Homes had side entrances used by extended family, or for rental basement suites.

Ayesha’s townhouse complex was old but well maintained, part of a larger neighbourhood made up of a high concentration of immigrants from Asia, the Caribbean and the West Indies. Their community also boasted the best kebabs, chicken tikka, dosa, sushi, pho and roti in the city, most of which were made in the kitchens of residents.

Nani was at the stove, stirring a fragrant curry and sprinkling minced coriander on top, when Ayesha and Nana walked into the kitchen. Her grandmother screwed up her nose at the smell of tobacco but otherwise kept silent.

“Challo, ghar agay, rani?” Nani said in Urdu. You’re home, princess? She added curry leaves to the pot before warming oil for mustard seed and black cumin in a separate frying pan, the final touch in every dal. She placed another pot on the stove and deftly filled it with milk, dropping in whole black peppercorns, cardamom pods, cinnamon sticks, cloves and three heaping teaspoons of loose-leaf black tea.

“Where’s Idris and Mom?” Ayesha asked her grandmother.

“Idris is in his room pretending to complete math homework. Saleha is on a double shift at the hospital until midnight,” Nani answered. Her grandmother spoke to her family in Urdu, though Ayesha knew she understood English perfectly.

Ayesha made her way upstairs, picking up socks, scattered mail and a jacket as she went. She opened her brother’s door without knocking. Idris was at his desk, hunched over the keyboard. The lights were off, and he whirled around when she flicked them on.

“Jesus! Can you knock?”

Idris was tall and had the lankiness of a teenager unused to his growing body. He was wiry and stubbly, but when Ayesha looked at him, she saw the little boy who used to beg her to play. His thick, black hair was standing on end from frequent finger-raking, and his glasses were smudged, obscuring his light brown eyes.

“I hear you’re hard at work. I had to see for myself,” she said.

Idris turned back to the screen. “Nani was nagging me again. I had to get her off my back.”

“You’re not watching porn, are you?”

Idris didn’t respond, and Ayesha peered over his shoulder.

“I emailed your math teacher. She said you didn’t do that great on your last test. Don’t forget your English essay on Hamlet is due next week. Nana said he’d help you annotate the play and think of a thesis.”

Idris hunched lower and typed faster.

“Did you hear me?”

“Yes! I heard you! Can you leave me alone?”

Ayesha sighed and placed her hand on her brother’s shoulder. “Are you writing code again?”

“Somebody’s gotta make it big in this family. It’s certainly not going to be you, Little Miss Poet.”

Ayesha was stung, but she squeezed her brother’s shoulder lightly. “Don’t forget me when you’re rich and famous.”

When she returned downstairs, her grandparents were drinking chai in silence. A large mug of milky tea was waiting for her, and she sipped the fragrant brew gratefully. Chai was so much more than a caffeine kick for her. She knew how every member of her family liked to drink their tea, how much sugar or honey to put in each cup. Chai was love, distilled and warming. She drank and relished the silence.

“Are you going to Hafsa’s house?” Nani asked after a few moments.

“It’s Bollywood Night.”

“‘Self-love is not so vile a sin as self-neglecting,’” Nana remarked into his mug.

Ayesha ignored his unsubtle jab at Hafsa and gulped the rest of her tea. “I’ll be back soon.”

WHEN they’d first immigrated from India to Canada, Ayesha and her family had moved into the three-bedroom townhouse with Hafsa’s family. It was a tight fit for everyone, but her uncle Sulaiman insisted on hosting them. He had immigrated as a young man almost two decades before, and he was happy to have his family join him in Canada, despite the devastating circumstances.

After two years of living together, Sulaiman, who owned several halal butchers and Indian restaurants in the city, gave the townhouse to Ayesha’s mother, mortgage-free. He constructed a new home on a parcel of land he had bought five blocks away, which he shared with his wife and four daughters.

“This is what family does,” he said. As eldest brother, it was his duty to take care of his widowed sister and their parents. The townhouse was a generous gift, one that Ayesha didn’t know how her family would ever repay. In return, she had looked out for her younger cousins, especially Hafsa.

It was a brisk fifteen-minute walk to her cousin’s house—which Ayesha secretly called the Taj Mahal. Sulaiman Mamu’s new home was large and ostentatious. It had never really appealed to her. He had built it envisioning a villa similar to the ones he had grown up admiring in the wealthy neighbourhoods of Hyderabad, so completely out of reach for the son of an English literature professor. The house was Spanish colonial, set well back from the road. With its adobe roof, sandstone walls and ten-foot-high custom-made door embellished with metal flowers and vines, the construction had initially drawn the ire and envy of neighbours. The building featured a large courtyard, circular driveway with stone fountain, four-car garage, six bedrooms and eight bathrooms. There was even a small guest cottage, kept ready for Nana and Nani whenever they wanted to spend the night. So far, they preferred their cozy basement suite in the townhouse.

The main house was decorated in bright colours, with dark maroon accent walls and warm syrupy-toned paint everywhere else. The floors were covered with red, blue and green wool rugs that had been imported from India. The wall decorations were Islamic prayers filigreed on metal, embroidered on tapestries and painted on canvas, and the large central family room had pictures of famous places of worship, including an oversized one of the Kaaba in Mecca. The furniture was traditional and ornate: overstuffed brocade couches, Queen Anne armchairs and heavy drapes. The light fixtures were all brass, polished weekly by a cleaning lady.

Hafsa’s mother, Samira, answered the door. She was a petite dumpling of a woman, round-faced and excitable, who had married young and birthed four daughters before she was thirty. She spent most of her days taking an avid interest in the goings-on of her neighbours.

“Ayesha jaanu!” she said, using the Urdu term of endearment. “You’re finally here! Hafsa was afraid you were too busy for her, now that you are working.” She enveloped her niece in a massive hug. “Let me fill you in on all the news. The Nalini girl ran away with her boyfriend, and the Patels are about to file for bankruptcy because their daughter is being far too demanding about jewellery and clothes for her wedding. She had her dress made by that fashionable Pakistani designer. So sad when people spend money they don’t have, no? Also, Yusuf bhai down the road is divorcing his second wife! Imagine!”

Ayesha’s eyes twinkled. “Samira Aunty, you’re better than CNN. Do you have a newsfeed I can subscribe to?”

Hafsa’s three younger sisters—Maliha, sixteen; Nisa, fourteen; and baby Hira, eleven—all rushed toward Ayesha.

“How do you like being a substitute teacher?” Maliha asked. “Dad said teaching is a good job for a woman. He refuses to consider enrolling me in the engineering program in New York City because he said it’s too far from home and he would miss me.” Her cousin rolled her eyes. “Can you try to convince him? Please?”

“Are we going for bubble tea this weekend? You promised!” Hira piped up.

“Did Ammi tell you about the rishta proposals that came for Hafsa?” Nisa asked. “Five this week.”

“Nisa, chup!” Samira Aunty reprimanded her daughter, and there was an awkward moment as all three girls looked at the floor, embarrassed.

“Only five?” Ayesha asked lightly. “I’m surprised Hafsa hasn’t received fifty proposals this week alone.”

The girls exchanged knowing looks and Ayesha’s cheeks turned red. Samira shooed her daughters away before turning to her niece.

“Ayesha jaanu,” she began carefully. “Since you brought it up . . . Well, I hope you aren’t comparing your situation to our little Hafsa’s many rishta proposals. Even if you are seven years older and only received a handful of offers. Only consider Sulaiman’s status in the community and Hafsa’s great beauty, her bubbly personality. Well, we are all blessed by Allah in different ways.”

Ayesha knew her aunt was trying to be kind, in her way. “Don’t worry about me. I’m too busy to go husband shopping.”

Samira Aunty smiled, but a look of pity was still fixed on her face. “Just don’t leave it too late. I was married at seventeen, and Hafsa will be married before the end of the summer. A girl’s beauty blooms at twenty, twenty-one. After that, well . . . Finding the right person can be difficult. Perhaps I can send a few proposals your way. The ones that aren’t suitable for Hafsa.”

Ayesha’s mouth twitched, but she kept a straight face. “Thank you. I promise I will think seriously about your offer.”

In truth, the only thing Ayesha envied her cousin was her massive bedroom suite. Hafsa had a separate seating area, with a large bay window and cozy reading nook. Her walk-in closet was the size of Ayesha’s bedroom, and best of all, one entire wall contained a built-in bookcase filled with books that her cousin, never a great reader, kept for decoration. The room was painted a screaming hot pink, Hafsa’s favourite colour.

Hafsa was in her room, sprawled on the reclining leather sofa in front of a sixty-five-inch flat screen TV so thin it resembled a painting. Two boxes of pizza and chicken wings and a bowl of halal gummy bears were in front of her.

“Apa!” Hafsa squealed. Apa meant “big sister” in Urdu, an honorary title. “What took you so long?”

“I was talking to your mom.”

“They didn’t tell you about my proposals, did they?” Hafsa’s mouth pursed in a pout. “I wanted to tell you first. Here, check out the pictures. They’re hilarious.”

Her cousin was wearing yoga pants and a furry pink hoodie that exposed her flat stomach when she reached for her cell phone. Samira Aunty was not idly boasting—her twenty-year-old daughter was lovely. With large eyes framed by dark lashes, the high cheekbones of a Hollywood starlet and a sweet smile, Hafsa was easily the most beautiful girl in the neighbourhood. She was always laughing and joking, the incandescent centre of every social gathering. In contrast, Ayesha was the calm, steady, responsible cousin. The boring one, she thought wryly.

Hafsa passed Ayesha her cell phone, to examine the pictures of her suitors. “I missed you so much!”

“It’s only been a week. I saw you on Monday when you told me your news. Haven’t you been busy with school?”

“I’m not really sure interior design is the right fit for me,” Hafsa said. “I told Abba that I’m super interested in event planning. I could start by planning my wedding and then launch my business.”

Ayesha reached for a slice of pepperoni and pineapple pizza and a handful of honey-garlic chicken wings. “So you’ve already picked one of the five proposals?” she asked, scrolling through the pictures.

Traditional arranged marriages were a bit like horse trading, Ayesha had always thought. Photographs and marriage resumés detailing age, height, weight, skin colour, job title and salary were sent to the families of prospective brides and grooms before the first visit was even arranged, a sort of vetting process for both parties. Details about family were often sent through a trusted intermediary, usually a mutual friend and sometimes a semi-professional matchmaking aunty.

Hafsa looked over Ayesha’s shoulder, supplying details—this one was a doctor, that one lived in India and was obviously looking for a visa-bride. This one had a pushy mother.

“All rejects. I’m not going to pick a husband until I get a hundred proposals.”

Ayesha laughed. “Why not hold out for a thousand?”

Hafsa squinted at her cousin. “I don’t want to be unreasonable. If I’m going to be a kick-ass wedding planner, I need to start now, when I’m young.”

“Yes, launching a business is a great reason to get married,” Ayesha said.

“You know what would be even better?” Hafsa said, ignoring her cousin’s sarcasm. “A storybook romance. Every business needs a good origin story. If I met someone who swept me off my feet, imagine how great that would play for my clients. I could call my company ‘Happily Ever After Event Planning.’”

“Or you could just start a company without the wedding.”

“Don’t be silly, Ashi Apa,” Hafsa said. “I don’t want to turn into one of those women who never gets married. No offence.”

None taken, Ayesha thought as she took another slice of pizza. She pressed Play on a nineties Bollywood classic, Pardes, and the girls settled in to watch the movie together.

It was after midnight when the movie finished, and Hafsa was fast asleep on the couch, curled up under a pink cashmere throw. Ayesha gathered the half-empty pizza box and empty wings container, turned off the TV and closed the bedroom door.

The light was on in the dining room when she crept downstairs, her uncle Sulaiman at the large table with stacks of paper in front of him.

“Ayesha.” He smiled, standing up to embrace her. “I didn’t know you were here.”

Her uncle resembled a kindly shopkeeper rather than the family saviour. He was a portly man a few inches taller than his niece and dressed even at this late hour in a white-collared shirt and dress pants, though he had removed his jacket and tie.

“I wanted to talk to you about something.” He motioned to the chair. “I am so proud of your hard work and choice of profession. We were a little concerned when you started performing those poems, but I told Saleha you would settle down. Teaching is a good job for a woman.”

“Thank you, Mamu,” she said. “I’m going to start paying you back for my tuition as soon as I get my first paycheque.”

Sulaiman Mamu waved his hand magnanimously. “I am worried about Hafsa. She told me she wants to be an event planner now, but I am afraid this is another phase, like all the others.”

“Hafsa has many interests,” Ayesha said diplomatically. So far Hafsa had tried her hand at cosmetology, landscape design and culinary school, and she had yet to complete any of the programs she’d started.

“I have a favour to ask of you. As you know, I am involved in the masjid,” he said, referring to the mosque.

Ayesha smiled. Her uncle was more than just involved. He had spearheaded the mosque building committee and donated generously over the years. Everyone knew he was the reason the Toronto Muslim Assembly could afford to keep the lights on and salaries paid.