6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

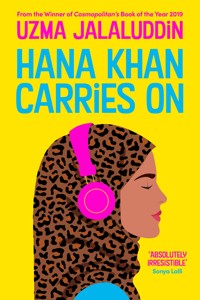

One of Washington Post's best romance novels of 2021 _________________________ From the author of Ayesha At Last comes a sparkling new rom-com for fans of You've Got Mail. Hana Khan's family-run halal restaurant is on its last legs. So when a flashy competitor gets ready to open nearby, bringing their inevitable closure even closer, she turns to her anonymously-hosted podcast, and her lively and long-lasting relationship with one of her listeners, for advice. But a hate-motivated attack on their neighbourhood complicates the situation further, as does Hana's growing attraction for Aydin, the young owner of the rival business. Who might not be a complete stranger after all... A charmingly refreshing and modern love story, Uzma Jalaluddin's tale is humorously warm and filled with gorgeous characters you won't be able to forget. Now in development for film with Mindy Kaling and Amazon Studios.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

HANA KHANCARRIES ON

Also by Uzma Jalaluddin

Ayesha at Last

First published in Canada in 2021 by Harper Avenue, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.

This edition published in paperback and export trade paperback in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Uzma Jalaluddin, 2021

The moral right of Uzma Jalaluddin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. Th e names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 361 4

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 356 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 357 7

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my parents, Mohammed and Azmat Jalaluddin, who taught me the importance of community, even as they built one.

Here are the rules:

This is a single-person podcast.

Not a variety show.

No interviews.

Not a comedy hour.

I’m not going to tell you my name or any specific biographical details, except the following: I’m a South Asian Muslim woman in my twenties. I was born and live in the city of Toronto. And I love radio. Really love it.

I also love the free form of podcasts. This particular podcast will be about having a place to ask questions, without worrying who might be listening and judging.

I’m talking about the Big Questions, future friends.

Such as: What do you want out of life?

What do we owe the people we love?

How do our histories and stories influence who we become?

And how do you know that the thing you want is actually the thing you want?

There you have it, listeners: my mission statement. I promise no frills and a clear voice. I promise nothing of substance and nothing but my truth. I promise to take this seriously, but I’m also definitely making it up as I go along.

Whoever and wherever you are, welcome to Ana’s Brown Girl Rambles. I can’t wait to start a conversation with you.

COMMENTS

StanleyP

This popped up in my podcatcher. Nice first episode. I’m always interested in the big questions.

AnaBGR

Is this for real, or are you a catfishing bot?

StanleyP

Real. Just pinched to make sure.

AnaBGR

Wow. Well, thanks for listening.

StanleyP

Sure. I’ve been asking myself the same questions, so thank you for the company.

AnaBGR

Definitely a bot. You’re way too polite. And now we’re trapped in a thank-you-cycle.

StanleyP

No escape from the thank-you vortex. This is home now.

AnaBGR

Except I know the safety words: you’re welcome.

StanleyP

Bots never give up. Until next time, Ana-nonymous.

Chapter One

StanleyP

Happy five month pod-iversary!

According to inaccuratestatistics.com, most podcasts don’t make it past month four, so you’ve beat the odds! I’d send you flowers, but that would imply I knew your name, mailing address, and flower preference, and that would cause my bot senses to melt into a confused puddle.

AnaBGR

That might be amusing. Okay, my real name is . . .

StanleyP

Wait. What? Seriously?

AnaBGR

Psych. Psych psych psych!

StanleyP

So cruel, when I’m trying to congratulate you. Any news on the mysterious dream-job interview?

AnaBGR

No news is good news, right?

StanleyP

Definitely. Especially when you’re going after the highly specialized job of . . . unicorn wrangler? toddler exorcist? erotic knitter?

AnaBGR

An erotic knitter can’t possibly be a thing.

StanleyP

You’re saying you’re definitely NOT a paper-folding priestess.

AnaBGR

That’s as likely as anyone under the age of 40 actually being named Stanley.

StanleyP

I’ve offered to reveal my true identity. Aren’t you a little curious about the incredibly hot, accomplished, muscular man behind StanleyP?

Was I curious about StanleyP? He had no idea.

I was in the corner booth of Three Sisters Biryani Poutine, the restaurant my family owned and ran in the heart of the Golden Crescent neighbourhood, in the east end of Toronto. I was supposed to be cleaning in anticipation of customers, but instead I was texting StanleyP, my very first and most loyal listener.

Over the past five months, we had moved from polite commenter and podcaster to friendly acquaintances to genuine friends who texted every day. All without exchanging a single personal detail. Yet when I closed my eyes, I could imagine his smile. It would be shy, tentative. He would be kind—a thinker and listener, with a mischievous glint in his eye. I knew I would love his laugh.

The phone pinged in my hand. I looked down at the direct messaging app we had started using a few months after he first began commenting on my podcast.

StanleyP

I think you might be the person who knows me best in the world right now. And I don’t even know your real name.

My fingers hovered over the screen. I could tell him who I really was. I pictured myself typing it out:

My real name is Hana. I’m 24 and I live with my parents in the most diverse suburb in the world—Scarborough, in the east end of Toronto. You already know that I’m a South Asian Muslim, but you don’t know that I wear hijab and I work two jobs. One is at Three Sisters Biryani Poutine, the restaurant my mother has been running for the past 15 years, and another at CJKP, a local indie radio station where I intern. Though “work” is a bit of a misnomer—neither position pays me actual money, and both positions have a limited life expectancy. The former because our restaurant is in trouble, and the latter because my internship is coming to an end and I have no idea what comes next. I’m trying not to panic about either situation.

Nope. StanleyP didn’t need to know any of that. Better stick with simple biographical details:

I have an older sister named Fazeela and a brother-in-law named Fahim, and in about four months they will make me a khala (that means “aunt,” in case you are a non-Urdu-speaking StanleyP). As for my dad . . .

I hesitated.

As for my dad . . .

It had been a long time since I had had to explain about Baba to a stranger. It used to be a daily occurrence as we navigated among hospitals, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and personal support workers. As Baba’s condition stabilized, his world had shrunk, along with the need for explanations to strangers. In that surreal way that online friendships worked, StanleyP was still, technically, a stranger. A stranger I spoke with daily, one who knew my deepest hopes and fears, but not any details about my real, lived existence.

I picked up my phone and typed carefully.

AnaBGR

It’s easier if we keep things the way they’ve always been. There’s a lot going on in my life right now, and I’m not sure I can handle another complication.

Another, longer pause. Imaginary StanleyP had his brow furrowed, but he would understand, and he would respond. He always had a response.

StanleyP

Is this complication . . . relationship-shaped?

I almost laughed out loud at the question—but then my mother would have realized I was goofing off in the dining room and make me help her in the restaurant kitchen.

Things had shifted between Stanley and me over the past month. Lately he had been hinting at more but had never come out and asked. But then, neither had I.

AnaBGR

More what-does-the-future-hold-shaped. A relationship would be easier to deal with than family and business stuff.

StanleyP

Our lives are running parallel. I have business-and-family-shaped complications too. That new project I was telling you about is finally happening. No relationship-shaped complication for me either.

StanleyP was single too. A flush crept along my collarbone and up through the roots of my hair, which was pulled back neatly under my bright pink hijab. I shifted in my seat. He probably hadn’t always been single like me, but still. I knew what he wasn’t asking me. And part of me was tempted to not answer back. Instead, I fell back into our usual humour.

AnaBGR

Why can’t I be the complicated one? You always have to copy me.

StanleyP

It’s what a bot does. The Stanbot is also programmed to give excellent advice and tell hilarious jokes, and is available for revelations of real names or the exchange of pictures/phone numbers. Just say the word. I’d love to get to know you better.

My stomach jolted with awareness at his words. I wanted more too. But it wasn’t as easy for me. All the bravery I possessed was currently being put towards other things. I wasn’t sure I had the energy to pursue whatever this thing between us was turning out to be.

I didn’t know anything about Stanley beyond what he had told me. From hints he had dropped, I knew he lived in Canada and was a second-generation immigrant like me. I suspected he was South Asian, maybe even Muslim, but I didn’t know anything for sure, and I wasn’t quite ready to venture outside the comfort of our cozy anonymous relationship.

I was saved from responding by his next message.

StanleyP

Message me when you hear you got the job.

I closed the app. Mom emerged from the kitchen a few moments later, ostensibly to deliver my lunch but really to check that I was working. I was distracted from my annoyance by the treat she held in her hand: biryani poutine, my favourite.

“Hana, beta, eat fast. Customers could come at any time, meri jaan,” she said, handing me the steaming plate piled high. My mother, Ghufran Khan, was a curious combination of nurturing and stern. She delivered orders in sharp bursts punctuated with Urdu endearments such as beta (child) and meri jaan (my life).

I devoured the mixture of fragrant rice, marinated chicken, crispy fries, savoury gravy, and cheese curds. Mom wrinkled her nose and hastily returned to the kitchen. Biryani poutine is . . . an acquired taste. As in, I was the only person who had acquired a taste for our restaurant’s namesake dish.

Biryani is a popular north Indian dish, a casserole made from basmati rice layered on top of meat or chicken marinated in yogurt, salt, fresh coriander, a garlic-ginger paste, and garam masala. The dish was topped with ghee and saffron and then baked. Poutine is a regional Canadian dish that first gained popularity in Quebec. It consists of fresh-cut golden fries topped with rich, savoury gravy and fresh cheese curds. Biryani layered with poutine was a strange combination that, so far, appealed only to me. Likely because I dreamt up the dish when I was nine years old.

My sister, brother-in-law, and even random strangers thought biryani poutine was disgusting. Eventually Mom had taken it off the menu after our customers complained, though she still made it for me. It had stuck as the name for the restaurant, probably because Mom hadn’t wanted to pay for a new sign.

I put down the plate and, popping in ear buds and cranking my favourite playlist, I began cleaning. After a few minutes I picked up the plate to take another bite of my lunch, swivelling my hips to TSwift’s infectious pop and using my spoon as a microphone.

Someone tapped me on the shoulder, and startled, I dropped my plate. Demonstrating lightning-fast reflexes, the someone—a young man, I observed—saved my lunch from disaster. I took out my earbuds, and TSwift’s bouncing lyrics blared for a moment into the silence before I hastily swiped the app closed.

The young man half-smiled. Cute, I thought.

“Your . . . meal?” he asked, his tone deeply dubious as he handed back the plate. He looked to be about my age or slightly older, wearing a black T-shirt and jeans. A pair of flashy sunglasses with reflective silver lenses dangled from his collar. His hair was dark and curly, and a smile twitched at the corners of his full mouth. A hint of stubble accentuated a square jaw and warm terracotta skin. Large, dark brown eyes regarded me from beneath thick black brows.

Definitely cute, but I didn’t appreciate the questioning lilt at the end of that sentence. Or the way the older man standing behind him wrinkled his nose at my lunch.

“What is that?” the older man asked. Despite the salt-and-pepper hair and the deep frown lines etched into his cheeks, the resemblance between the two was clear. Father and son, I concluded.

“Biryani poutine,” I answered, offended. “Only available on the VIP menu.”

The older man frowned at my mop, which had fallen to the floor. “You work here? You look about fourteen years old.”

I reached up to straighten my wrinkled black tunic and adjust my hijab. The young man followed the movements of my hands with his eyes before looking away with a faint smile. Was Mr. Silver Shades laughing at me?

Welcome to Three Sisters Biryani Poutine, where child labour is encouraged and biryani and poutine are kept segregated, as God intended, I wanted to say. Instead I led them to a booth.

“I don’t understand why you insisted on coming here,” the older man said loudly, settling into his seat with a look of distaste. “They probably don’t even have clean cups.”

Charming. A few years ago I might have asked Mr. Silver Shades to take his grumpy dad elsewhere. But they were our first customers of the day, and my family couldn’t afford to be picky.

Three Sisters Biryani Poutine had seating for about forty people, spread out among a handful of plastic booths and yellowing square tables paired with wooden chairs. Bright fluorescent lighting painted every smudge and dent in harsh relief, and the walls were an unflattering green. Every year we meant to repaint, but time and money never allowed for it. Some art hung on the walls, mostly prints from IKEA or garage sales; Mom was partial to seascapes and large florals. A counter stood against the back wall, with the cash register in front of a door that led to the kitchen.

“These hole-in-the-wall places sometimes have excellent food, if you can look past the decor,” the young man said to his father, not bothering to lower his voice. He caught my eye when I returned with cutlery and glasses, unaware—or uncaring—that I had overheard. The older man immediately reached for his glass and started inspecting it for water blotches.

“Have you worked here long?” Mr. Silver Shades asked.

“A few years,” I said shortly, handing them laminated menus. I had officially started serving when I turned sixteen; before that I had helped out as dishwasher, sweeper—any job that needed to be done. Not that Mr. Silver Shades and his designer clothes would have any idea what a struggling family-run business required.

“There aren’t any other restaurants in the neighbourhood,” he remarked. “This area could use more selection, don’t you think?”

“No, I don’t,” I said. “Things are fine the way they’ve always been.”

Mr. Silver Shades perused the empty dining room dubiously. “I hope you have a backup plan for when this place shuts down. Shouldn’t be long now.”

I stared at him in shock. Had he really just said that my mother’s restaurant was on the brink of closing?

“Bring us some water,” the young man said, dismissing me outright. He turned his attention to our comprehensive menu, written in both English and Urdu. I walked away before I did something foolish, like empty the water jug over his head.

When we first opened, Three Sisters had been one of the few full-service restaurants that served halal meat, a fact that had enticed customers from all over the city. As Toronto’s Muslim population grew, more halal restaurants began to pop up all over the city. A demographic shift occurred at the same time: second-generation immigrant kids weren’t as interested in eating the South Asian staples their parents craved. Mr. Silver Shades was right. Three Sister Biryani Poutine had been open for fifteen years, but now we were in deep trouble.

“Your menu is very extensive. What would you recommend?” Mr. Silver Shades asked when I returned to take their order. Grumpy Dad had pulled out a pair of reading glasses and was examining his fork.

I rattled off our specialties, and the young man frowned at every choice, the notch above his eyebrows deepening with every word. He was contemplating walking out, I could tell. I knew Three Sisters would never win any prizes for beauty, but then, this man and his father would never win any prizes for grace.

“Why don’t you just order what you think we’d like,” he finally said. “Let’s make it four dishes, and some mango lassi.”

I chirped, “Sounds good!” and collected their menus. I wasn’t sure if I should feel relieved they had stayed to fill our till, or disappointed that they hadn’t left and saved me the trouble of serving people I disliked. Then again, they were probably strangers passing through Golden Crescent. I didn’t recognize either of them, and I knew most of the people who lived in the neighbourhood. After this meal, I hoped I would never have to see Mr. Silver Shades and his grumpy dad ever again.

Chapter Two

I gave Mom the order: chicken biryani, malai kofta, dal makhani, and naan, then hung around the kitchen while Fazeela, Fahim, and Mom worked.

My sister Fazeela was sous-chef for the day and Fahim was in charge of the large tandoor clay oven that turned dough instantly into soft, crispy naan, while Mom assembled the biryani. Fazee and Fahim were discussing their favourite topic: baby names for the little cantaloupe.

“Hussain is a good choice,” Fahim said, smiling. My brother-in-law was always smiling. A tall man with broad shoulders, he was rocking his usual outfit of dark Adidas track pants and hoodie, a perpetual athlete on his way to the gym. “That was my grandfather’s name.”

Fazeela shook her head. “Hussain is overplayed, like Hassan. Besides, we’re having a girl.”

“My cousin named her son Hassan. She’s the one I was telling you about, the one who just bought a house in Saskatoon. You won’t believe how little they paid. We should plan a visit to check it out.”

Fahim’s family lived in Saskatchewan, nearly three thousand kilometres from Toronto. My sister and brother-in-law had met in culinary school and married the previous year. Ever since Fazeela found out she was pregnant, Fahim hadn’t stopped talking about moving west. My sister was less enthusiastic, and I was tired of that conversation.

I opened the messaging app to see if StanleyP had texted again, but Fazeela’s teasing voice jolted me back to the kitchen.

“Are you talking to your mystery man again?” she asked, grinning. “It’s that internet guy, right? The one from your podcast.”

“You don’t even listen to my podcast,” I said, stashing the phone in my pocket.

“Marvin, or Alan, or Johnny, or—” Fazeela rattled off, ignoring me.

“Stanley,” I muttered, instantly regretting it.

“Stanley!” Fazeela crowed. “Some random white dude from who knows where, and you’re obsessed!”

“I’m not obsessed,” I said, flushing and looking at my mother. “We’re just friends. And how do you know he’s white?”

Fazeela looked at me in disbelief. “He listens to podcasts.”

She had me there. #PodcastsSoWhite.

“You text him more than I do Fahim, and we’re married. Should we be concerned, Hanaan?”

My sister was the only one in the family who insisted on calling me by my full name, Hanaan. That’s Hana with an extra an. At twenty-six she was two years older than me, and with her tall frame and impatient air, she looked like a younger version of our mother. When her athletic body, more used to running on a soccer pitch than standing around the kitchen, had begun to round with signs of new life, the resemblance had become remarkable.

Unlike Fazeela, I hadn’t inherited our mother’s tall, sturdy build. I was short, with tawny bronze skin and round hips. My eyes were hazel in the sun or after a bout of laughter, I had been told, but otherwise dark brown. My sister and I shared our mother’s full, slanting eyebrows and full lips, though mine were set in a small triangular face, in contrast to my sister’s more angular features.

“Leave her alone, Fazee,” Fahim said, looking over at me with sympathy. “Remember how we used to be when we were first getting to know each other?”

“He’s just a friend,” I muttered. “I don’t even know his real name.”

“If the online guy isn’t serious, there’s always Yusuf,” Fahim said to Fazeela. “He’s single, he’s nice. She could marry him.”

“She will decide for herself when and if she wants to marry,” I said firmly. “And Yusuf is my best friend.”

“They can’t all be your friends,” Fazeela shot back.

Mom usually stayed out of our low-level bickering, but now she pinned the three of us with a look, and we instantly shut up.

“Hana, beta, after you serve the customers, I need you to run home and check on Baba before you leave for the radio station. He isn’t picking up the phone,” Mom said as I carefully picked up the dishes they had prepared.

My mother thought about everyone and everything, all the time. I wondered how she managed it all. Perhaps if I got my dream job, the income would help take some of the burden from her shoulders.

“Don’t forget the mango lassi on your way out,” Mom said.

AFTER I SERVED MR. SILVER SHADES and his grumpy father, I moved to the front of the restaurant, delaying my departure. I was waiting for my favourite moment.

I knew Three Sisters Biryani Poutine wasn’t fancy. When Mr. Silver Shades and the old man had insulted the restaurant, I felt defensive because their easy dismissal was often the first reaction of new customers. Until they tasted our food.

Mom had haat ki maaza, which is untranslatable Urdu for “magical cooking hands.” The men tucked into their buttery dal makhani, lentil stew simmered with garlic and onions and topped with ghee. They soaked up malai kofta, dumplings made from mashed potato and paneer cheese, simmered in a tomato cream sauce, with fresh tandoori naan. They took sips of mango lassi, a fruit and yogurt smoothie, before digging into my mother’s signature dish, chicken biryani. She had learned the recipe back home in New Delhi, and I had never tasted that combination of delicate saffron and fragrant spices anywhere else.

As they tasted each dish, their eyebrows rose. They took more bites, unable to believe their taste buds. A slow smile blossomed on Mr. Silver Shades’ face, and it seemed real this time, not the polite expression he had worn when he told me to order his lunch. The men passed dishes back and forth. They closed their eyes in ecstasy as the complex flavours danced on their tongues.

Okay, I might have made that last part up. My mother is a good cook is what I mean. She might even be a cooking prodigy. It was how she had sustained the restaurant for all those years. So even though people hadn’t been breaking down the door lately clamouring for her Indian staples, she still had haat ki maaza.

“Everything all right?” I asked, walking past with a pitcher of water.

The older man kept eating. Mr. Silver Shades, on the other hand, slowed down, a tablespoon heaped with biryani rice paused halfway to his mouth.

“What’s wrong, too spicy?”

His father cracked a smile. That’s how good my mom’s food was: Grumpy Dad actually smiled.

The young man put the spoonful of rice in his mouth and chewed slowly. “It tastes like . . .” He looked disoriented. “Where did the chef learn to cook?” he asked me.

“Secret family recipe,” I answered smoothly. “My mother learned from her mother, who learned from her mother.”

“Your mother owns this restaurant?” Mr. Silver Shades asked, surprised. “I thought you were just the waitress.”

Definitely a jerk.

“It’s a family business,” I replied, and he looked briefly disconcerted. Good.

“Why so much interest?” Grumpy Dad said. “Be quiet and eat the food. Our appointment to inspect the property is in half an hour.”

“Are you moving into the neighbourhood?” I asked, filling up their glasses with water. Please say no, I thought.

The younger man didn’t answer, only shook his head and ate another spoonful of biryani. His eyes fluttered closed and he inhaled deeply.

“What’s your mom’s name?” he asked. He turned to look at me, and this time I understood the emotion in his eyes. Mr. Silver Shades looked sad.

His father’s brows drew together. “What is the problem?”

“This food, it reminds me of . . . the biryani reminds me of . . . Mom.” He sounded awkward, as if the word Mom was not one he used often.

Grumpy Dad dropped his spoon with a clatter. “Don’t talk nonsense. You don’t remember what her food tasted like. You were a child when she died.” He turned to me, brow thunderous, and I gripped the water pitcher tightly. This conversation felt too intimate. “Bring the bill, girl. Aydin can pay, since he wanted to check out this pile of dirt so badly.” He rose and strode out of the restaurant.

Mr. Silver Shades had seemed to shrink at his father’s words. Now he uncurled himself and removed a hundred-dollar bill from a sleek leather wallet. He placed it carefully on the table.

“Tell your mother the food was excellent,” he said, without looking at me.

Aydin. Mr. Silver Shades’ name was Aydin, and he missed his mother.

I pocketed the money and began to clear the table.

I DUMPED THE PLATES ON the counter of the kitchen and began emptying the contents into the garbage. I hated that part, throwing away half-eaten food. Sometimes we gave away food that hadn't been served to a shelter.

My mother looked at me, expressionless. “They didn’t like it?” she asked.

I hesitated. I wasn’t sure what had happened. Instead I took out the hundred-dollar bill, more than double what the food and tip cost together. “They liked it fine. They just had to leave, for an appointment.”

Fahim leaned against the counter. “One customer today, and they didn’t even finish their food.”

Mom picked up another plate and scraped it clean. “A few bad days only. We have run this place for fifteen years. There is no reason why your children will not one day work here during the summertime or after school, as you have done. It will all work out.” She said that last part almost to herself. My sister and brother-in-law exchanged a quick glance.

I wasn’t in the mood for the same conversation, the one that skirted the real question: How bad was it? Mom remained tight-lipped on the subject of our family finances, so we were all left to imagine the worst.

“I’ll be back to help with dinner,” I said instead.

They formed a tableau as I walked out: My sister, four months pregnant, her belly round, eyes lowered and eyebrows drawn together. My mother, absently stirring a pot of savoury chicken korma curry as Fahim loaded the dishwasher, his usual smile banished by worry.

That was their life. The life I had opted out of when I chose to pursue broadcast journalism.

Mom was big on choice. She hadn’t pushed me to join her full-time in the food business. Baba had never encouraged us to study accounting like him. When my sister decided to go to culinary school, my mother had been happy to welcome her, but only because she came into the restaurant world with eyes wide open, prepared to survive on hope and prayer.

Fifteen years ago, Three Sisters had been the only halal restaurant in the area. That wasn’t the case today, though we were still the only restaurant in Golden Crescent. It was ironic, then, that our origin story didn’t revolve around food at all.

Three Sisters Biryani Poutine had been conceived by soccer. Premier rep soccer. The kind that costs thousands of dollars a year and had been completely unaffordable on my father’s modest salary as a bookkeeper, even before his accident. But my sister Fazeela loved soccer, and she had been very, very good at it—ferocious and ambitious on the field in a way she had never been anywhere else. Mom supported my sister’s talent in the best way she knew: she paid for the expensive lessons by starting a catering business. A few years later, Three Sisters Biryani Poutine was born.

Then FIFA, the official governing body for international football, had enacted a new dress code that banned all “headgear.” The rule was unsubtly aimed at hijab-wearing Muslim female athletes. Fazeela had decided to stop playing soon afterwards.

I was pretty sure my sister was happy with her choices—she had Fahim, she had the little cantaloupe growing in her belly. But sometimes I wondered if she had made those choices because she felt she had to. Mom had started Three Sisters Biryani Poutine to pay for Fazeela’s soccer dreams. And when those dreams died, maybe my sister’s career choice had felt more like an inevitability.

Maybe I was the only one who would really get to choose anything. And I had chosen to get out.

Chapter Three

Three Sisters Biryani Poutine was located in a commercial strip surrounded by a dozen storefronts, all owned by first- and second-generation immigrant business owners. Luxmi Aunty ran the Tamil bakery next door, where she sold fresh-baked flatbread and fried savoury snacks such as samosas, chaat, and bhel puri, as well as Indian sweets. Sulaiman Uncle owned the halal butcher a few doors down. A florist shop that specialized in the elaborate garlands used in South Asian weddings and other celebrations stood beside a hair and nail salon that had curtains over the windows to accommodate hijab-wearing women looking for a blowout with some privacy. There was a convenience store that sold lottery tickets and henna cones, and a dry cleaner that knew how to get turmeric and oil stains out of clothes and offered an on-site seamstress.

The street was bookended by a Tim Hortons coffee shop at the north end, run by our business elder, Mr. Lewis, and at the south end by the hollowed-out shell of an abandoned storefront that had long ago been home to another restaurant. A tiny grocery stood directly across the street from Three Sisters, owned by my best friend Yusuf ’s Syrian family. Beside it was a computer and electronics repair shop that also offered wire money transfers around the world, and a South Asian bridal shop that specialized in bespoke lenghas and saris. The stores fronted the residential neighbourhood known as the Golden Crescent, named after its main street. According to local lore, the subdivision also formed the shape of a crescent on Google Maps.

I set off to check on Baba before my shift at the radio station, ducking around the back of the restaurant, through the parking lot, and deeper inside the Golden Crescent. Here the homes were built close together, semi-detached units and blocks of townhouses interspersed with two-storey houses with tiny front lawns. Driveways held two or three cars, usually minivans and older sedans. Extended families lived together, and basement tenants were common.

I turned onto my street, a cul-de-sac that backed onto a ravine. Our home was a split-level detached unit, and I ran up the half-dozen stairs to the front door, eyes resting briefly on the peeling paint that surrounded our large bay window. If Baba was having a good day, he would be dressed and seated in the living room, perhaps reading or working on a jigsaw puzzle. He would greet me with a smile and make a joke about how we worried unnecessarily, and I could text Mom with enough assurances to wipe the strain from her face.

But my father wasn’t sitting in the neat living room on his favourite chair. A quick look revealed that he wasn’t in the kitchen either, and there was no empty chai mug on the counter. I took the steps two at a time to the room my parents shared at the end of the hall. I knocked once and entered. He was still in bed.

“I tried to get up,” Baba said, greeting me with an apologetic smile. “I’m feeling shaky today, and I didn’t want to fall again.”

Ijaz Khan was a diminutive man, and he seemed even more shrunken under the duvet. His face looked as if it had been assembled from mismatched Mr. Potato Head parts—dark slash of unibrow, large, bulbous nose, full lips, receding hairline—all on a beloved face. He wore oversized reading glasses that magnified his dark eyes. Mom had been right to send me; it was obvious he was in pain.

“Should I get your pills?” I asked gently. He nodded, and I went to the bathroom for his medication. I hated seeing him this way.

Two years ago my father’s car had been struck by an SUV making a left turn, his compact sedan pushed into oncoming traffic, legs pinned by the wreckage. For a few weeks afterwards we hadn’t been sure if he would ever walk again. Most of the insurance settlement went to paying for extra therapy, medicine, and help after the accident, and he hadn’t worked regularly since. Before the accident my father had counted most of the businesses on Golden Crescent among his bookkeeping clients. Now he managed only a handful of storeowners loyal to him. Our family’s ability to pay bills in a timely manner rested largely on the success of Three Sisters Biryani Poutine.

While we waited for his medicine to kick in, I switched on the radio he kept on the night table, tuned to the CBC. We listened to the last ten minutes of a tech program until he felt steady enough to grasp the handles of the walker I had moved near.

I helped Baba make his way down the steps, then busied myself in the kitchen, boiling water and heating milk for chai. He hated when I hovered. I buttered toast and brought his meal to the white plastic kitchen table.

“Play one of your podcast episodes, Hana beta,” he said after taking a restorative sip of scalding hot chai. I had made a mug of the strong, milky tea for myself as well, and we settled down to listen. Baba was the only one in my family who had thought my podcast was a good idea. I scrolled to an episode I thought he would like, and pressed Play.

• • •

Welcome to Ana’s Brown Girl Rambles, an anonymous podcast about life as a twenty-something Muslim woman in Canada.

I come from a long line of storytellers. My father loved to tell stories about his family and growing up in India. My sister and I never grew tired of hearing those tales. One of our favourite stories was about my father’s oldest brother, who loved to play tricks on his siblings. One day their youngest sister and her friends were play-acting a wedding between their dolls, and my uncle insisted on participating. He would play the part of the imam and marry the dolls. He dressed up in a long robe and prayer cap, and when the time came for the wedding feast, my sister and her friends provided snacks: cakes, and sweet sherbet to drink. Naturally, the minute the nikah was over, my uncle had his friends swoop in and steal all the food, while he kidnapped the newly married dolls and held them for ransom in his hideout on the roof. He didn’t let them go until his little sister and her friends agreed to hand over the bride’s dowry—three bottles of cola, a toy car, and a handful of rupees.

Baba laughed aloud at my retelling of his mischievous brother’s long-ago antics. While he listened to the rest of the podcast, I skimmed the comments.

COMMENTS

StanleyP

I’d like to meet your uncle.

AnaBGR

I haven’t seen him in years, but he’s a joker even as an adult.

StanleyP

All my relatives are boring.

AnaBGR

Do bots have family?

StanleyP

Only the cool ones, like me. It helps us appear more realistic. How’s work going?

AnaBGR

Busy, occasionally soul-sucking, scattered with moments of awesome. You?

StanleyP

I tried pitching my idea the way you suggested. It didn’t go over well.

AnaBGR

You need to make your slide deck pop. I told you to add a catchy playlist.

StanleyP

You’ve never worked in an office before, have you.

AnaBGR

Fine, don’t listen to my excellent advice.

StanleyP

Nobody should, actually.

AnaBGR

And yet my listener count is up again. I didn’t think anyone would be interested.

StanleyP

Yes, you did. Or you wouldn’t have bothered.

AnaBGR

How do you know that?

StanleyP

You got me hooked.

My stomach knotted as I reread StanleyP’s words from only a few months ago. This casual flirtation was starting to feel dangerous. What were we doing?

As my podcast self signed off, I looked for Baba’s reaction. His wide grin wiped away the lines deeply etched around his mouth, so that he looked almost like the person he had been before the accident. My heart clenched at the sight of his fleeting joy.

Baba had been so happy when I decided to pursue a master’s in broadcast journalism, so proud of my internship. He spent so much time at home now, listening to the radio or to podcasts online, that he had become convinced I would soon be given my own show. So far all I had done at my internship was sort archives and research stories. I had graduated the previous June and was still waiting to figure out my next move.

I deposited his empty plate and mug in the sink. “I’ll be back late,” I said. “I’m at the radio station, and then closing the restaurant afterward.”

Baba nodded, hesitating. “How many customers today?” he asked.

I kept my face averted when I answered. “A slow day. Nothing to worry about.”

“Things will get better,” he said. “Inshallah.”

I squeezed his shoulder, then pulled out the tray that held his latest jigsaw puzzle: a Scottish castle, five thousand pieces. I set it up on the coffee table before letting myself out the front door.

My phone pinged with a new email as I stepped onto the sidewalk. It was from the public radio broadcaster—the dream job StanleyP had asked me about earlier. Please, Allah, I prayed fervently. My fingers fumbled as I opened the email app. Please, please, let this be good news. I read quickly, eyes skimming, heart pounding.

Dear Ms. Khan,

Thank you for your interest in the position of junior producer. We regret to inform you the position has been filled. We thank you for participating in our interview process, as we encourage diverse voices to continue to apply and make a difference in the Canadian media landscape . . .

I deleted the message before reading the rest, and my fingers automatically moved to the messaging app. I didn’t get the job, I typed to StanleyP, but then my fingers stilled.

Maybe this rejection was a sign that I should focus on what was happening right now, and not worry about dream jobs, or future relationships, that were out of my reach. I erased the message and walked to the bus stop. My dreams could wait a little while longer.

• • •

Welcome to Ana’s Brown Girl Rambles, a podcast about the life of a twenty-something Muslim woman in Toronto.

One of the questions I posed in my first episode was about family. What do we owe the people who grew us up, who first made up our entire world?

It’s complicated for the kids of immigrants. I’m not talking about the usual “my parents don’t understand” thing. My parents believe in the power of choice, and they never asked me to sacrifice my dreams for theirs. Yet I feel like I should anyway. Where does that feeling come from? Is it just loyalty and strong family ties? Is it because, as part of a marginalized community, we all had to stick together to survive, and that sort of experience tends to become habit? Maybe it’s about guilt. We are kids who benefited from the sacrifices our parents made when they decided to move to a richer, safer country. If we then grow up to grow apart, have we become ungrateful villains?

My parents would say I’m being dramatic. Maybe I am. Then again, the beauty of running an anonymous podcast is that I can be as dramatic as I like.

I do know that, for all the benefits of being the daughter of immigrants, the one drawback is I’ve had to establish my own sense of place. All my extended family live elsewhere, on a different continent, and we don’t visit often enough to form real ties. There’s a lot of freedom in being a pioneer of your family’s history in a new place, of course. But there’s a lot of loneliness too. I’ve had to find my own family, to make the sort of friendships that are family. Yet that lack of history means my roots here are shallow, my stories only a few years old.

Maybe that’s why I’m feeling so restless today, a little bit stuck. I’m waiting for something, only I’m not sure what. This is when I imagine a different sort of restlessness—the kind my parents felt, the kind that drove them to get on a plane decades ago and leave behind their own world, full of stories and history, for something new.

In so many ways the choices they made have limited mine. No doubt the choices I make will do the same for the generation that follows. I guess we all make peace with that in the end.

Thanks for listening, friends. Let me know if you have similar stories and how you’ve navigated your own road.

COMMENTS

StanleyP

Great second episode!

AnaBGR

The bot returns.

StanleyP

I subscribed. I guess I’m a fan. My fam isn’t as understanding as yours, but I feel you about the loyalty, and the guilt. Can’t wait to hear what you come up with next. You should do this for a living.

AnaBGR

Inshallah.

StanleyP

God willing.

AnaBGR

Are you Muslim too?

StanleyP

Anony-Ana, if I answer that question, will you answer some of mine?

AnaBGR

Nope. Withdrawn.

StanleyP

Until next time.

Chapter Four

Radio Toronto was a popular indie station that aired a little of everything. We played local artists as well as Top 40 hits, reported on serious news as well as Toronto street culture. I had beaten hundreds of other applicants to secure my internship position, alongside fellow intern Thomas Matthews. Now that I had lost out on the only other job I really wanted, I was determined to get hired on permanently at the station once my internship ended. To do that, I needed to become indispensable to the station’s general manager. Marisa Lake was a sophisticated white woman in her late thirties, tall and willowy, with sleek honey-brown hair pulled into a chignon and a silk scarf draped just so around her neck. Thomas, my fellow intern, thought she was sensitive about her neck.

“You’re lucky, you cover all the time,” he said now, gesturing at my hijab. We were sitting in our small office, surrounded by boxes of archives that hadn’t been touched in decades. Our task was to sort and catalogue, and after two hours, we were both bored.