5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Spy Pond Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

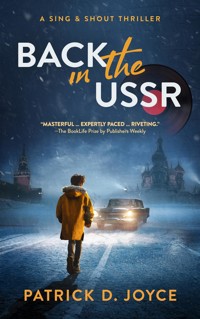

Embark on a thrilling adventure to an enemy capital, where two teenagers race against spies and mobsters to recover a priceless vinyl record that just might save the world.

When Harrison, the son of American diplomats, lands in Moscow at the height of the Cold War, he knows three things: his passport will keep him safe, his daydreams will keep him company, and his music will keep him sane.

But everything he knows is about to be shattered.

His father has vanished, his mother is keeping secrets, and his best friend Prudence, the fearless daughter of foreign correspondents, leads him on a dangerous pursuit of a mysterious femme fatale.

Suddenly they're on the run from the CIA, the KGB, and an assortment of treasure hunters, all desperate to get their hands on a legendary lost Beatles record in a place where rock music is banned.

Their only hope is to navigate a treacherous underworld — a world of coded messages, secret gatherings, maps made by spies, walls that have ears, cellars dripping with menace, skyscrapers that trap you in the clouds, and elevators whose rides could be your last.

As the Cold War threatens to heat up, Harrison turns to the last person he ought to trust — a renegade spy on a mission of personal redemption — and learns the timeless lesson that love is all you need.

Full of suspense,

Back in the USSR is perfect for fans of

Code Name Verity and

I Must Betray You, and a great next step after

City Spies,

The Bletchley Riddle, and

Alex Rider. It will keep you on the edge of your seat right up to the emotional, uplifting ending.

Buy now to be transported to a world of secrets and spies!

"MASTERFUL ... EXPERTLY PACED ... RIVETING ... 10 OUT OF 10." -

The BookLife Prize by Publishers Weekly

"A book about rock 'n' roll and its power to fight suppression, feed the human spirit and kick butt." -

Goodreads review

“Read this in two days – couldn’t put it down.”

-Goodreads review

"Vividly painted and irresistible … a fun, rich, and sophisticated page-turner … Highly recommended!" -

Tim Weed, award-winning author of the young adult adventure Will Poole's Island

“I completely fangirl

Back in the USSR by Patrick D. Joyce.” -

A License to Quill blog

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Published by Spy Pond Press 125 Mount Auburn St., #380657, Cambridge, MA 02238www.spypondpress.com [email protected]

Copyright © 2022 by Patrick D. Joyce

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

ISBN 979-8-9861699-0-3 (ebook)ISBN 979-8-9861699-1-0 (paperback)ISBN 979-8-9861699-2-7 (hardback)

This is a work of the imagination in its entirety. All names, settings, incidents, and dialogue have been invented, and when real places, products, and public figures are mentioned in the story, they are used fictionally and without any claim of endorsement or affiliation. Any resemblance between characters in the novel and real people is strictly a coincidence.

Cover design by Damonza.comSpy Pond Press logo design by Priya K. JoyceInterior LP record image by JeksonGraphics/Shutterstock.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022917227

24061107

If you enjoy this book, visit patrickdjoyce.com, where you can sign up for author updates and receive a free short story.

For my parents

Side One

The Airport

Jet planes screamed down the runway, thumping and skidding. An electric guitar twanged. Drums rolled to a crescendo.

I carried my Walkman with me overseas and across continents, but in truth, I didn’t need it. I heard the songs in my head. Here in the enemy capital, they'd keep me sane. My passport would keep me safe. And my daydreams, they’d keep me company.

My breath condensed on the glass as I watched through the terminal window. It made no difference to the view. Moscow winter painted the sky a dull bronze, wrapped the hangars in a dull beige, and coated the tarmac in a dull powder.

Inside, the arrival gate smelled like stale bread. It was standing room only by the time I got there, and the lucky people sitting in the cracked plastic seats stared into space out of dead eyes. The militsiya weren’t letting anyone through customs.

We’d been waiting an hour or more when it happened. A shift in the air, a buzz, a vibration. It dislodged the haze from my mind. I turned. The crowd parted, and she appeared.

She snapped orders in Russian at the underlings who swarmed around her as they tried to keep up. You could have mistaken her for nobility, if we hadn’t been in a communist state. She radiated power and purpose, from the way she moved right down to the point of her nose and the angle of her cheeks.

She was utterly beautiful, like no one I’d ever seen.

Straight, dark hair fell to her neck. A long coat swept behind her. She glided like her feet didn’t touch the ground, and she wore a smirk that said she belonged to a different world.

I belonged to a different world too — a boarding school in Connecticut, the Charles Froate Hall Academy. About as different a world as there was from the Soviet Union. But I was back in the USSR, just arrived from New York via Frankfurt on one of those screaming, skidding Aeroflot jets.

The mystery woman glanced my way. She did it casually, and gave no outward hint she noticed me, but I’ll never forget what I saw in her eyes. Dreams took shape in their depths. Visions flashed. They lasted a moment, then were gone.

She floated forward. A soldier with a red star on his olive jacket snapped to attention. He scurried to open a swinging panel to give her passage, and she disappeared.

I couldn’t tear my gaze from the spot. Her aura lingered, and I stood there, hoping, maybe, she’d come back.

Instead, a voice crackled over the loudspeaker. All the machinery of Sheremetyevo International Airport swung into action. The customs booths filled up with officers, the plastic seats emptied, and the masses lined up before I could move from my window.

Somehow, the beat of my pulse overpowered the fog in my brain. All I knew was that I had to catch another glimpse.

I’d gone through the customs ritual before, so I knew what had to be done. I slipped around the back of the crowd to the far side, where the booth said “Диплома́ты.” Diplomats.

I’d evaded the proletariat. Now I faced the bureaucracy and its glacial cogs.

I slid my passport under triple-paned glass. The Soviet officer took his time. He studied the document, cocked an eyebrow, stamped a page, triple-stamped another. I was only a teenager. He didn’t want to harass me. He wanted to get out of his booth, go home to his wife.

He held my passport up, jammed a finger at it, and spoke, finally, in stilted English.

“This is you?”

I tried to approximate my sleepy expression in the photo — it was easy — and nodded.

“Age?”

“Fourteen.”

“Purpose of travel?”

For a boy carrying a diplomatic passport, it should’ve been obvious. I wanted to say, Well, it’s not for pleasure, I can tell you that much.

“Visiting my parents. At the U.S. Embassy.”

As he scribbled, cocked, and stamped, I bounced on my toes, trying to see past customs. Partitions blocked the way. I swiveled to face the thick lines I’d skirted.

One consisted of foreigners, non-diplomats, marked by bright clothing against a dominant palette of glum. Soon they’d be taken under wing by Intourist, the state travel agency, whose guides would follow them everywhere. The guides did double duty as spies, monitoring visitors and reporting their movements to state security. Everyone knew it. Nobody blamed them. It was their job.

Soviet citizens made up the rest. Customs officers with gloved hands pulled at straps and tugged at zippers. They rifled through carry-ons, extracted underwear, examined rolled-up socks, all in search of smuggled Deutsche Marks or other contraband. One guard confiscated a paper bag full of cigarette packs. Another drew an LP record out of a briefcase like a rabbit from a hat and scratched a key across the shiny black surface. Its owner looked on numbly.

Meanwhile, my bags would go untouched.

It was a privilege, but it wasn’t only that. It was a separation for Western diplomats that pervaded every aspect of our life in Moscow, beginning right here. They wanted to keep us in a cocoon from the moment we entered the country to the moment we left. We could go every day with little or no contact with ordinary Russians. We lived in designated buildings, worked in guarded compounds, and socialized in our own tight-knit diplomatic communities.

Cracks in the barriers could open, and Westerners could widen them. But it meant taking risks. For the Russians. And for us.

I didn’t like risks. All I wanted for my winter break was to be left alone.

The officer grunted, and I turned back. He slid my passport through the glass, flaunting a toothy grin. I snatched it off the counter and shuffled off. If I hurried, maybe, I could catch her.

Before I’d gone three steps, a voice echoed in my head. My father’s.

Flip through the pages. Every time. Make sure every stamp has the right date. Make sure they give you back your passport, not someone else’s. Remember, they’re always watching, waiting for you to slip up. You have to pay attention to every detail.

The thought of losing my diplomatic passport, my little shield, paralyzed me. I stopped. Flipped through the pages, checked every stamp.

And lost my advantage. The masses started to reconvene on this side of customs, moving slower than molasses toward the baggage claim. I pushed through.

In New York and Frankfurt, Instamatics snapped away as happy travelers reunited with friends and family. Not here. No photos at Sheremetyevo. It was absolutely forbidden, the absence of flashes leaving the atmosphere eerily subdued.

I stood on my toes again, craned my neck in every direction. She was gone.

Instead, a stocky man with a bushy mustache stood in my path, squinting at me. He was the spitting image of Josef Stalin, the dictator who had ruled the USSR with an iron fist. But he carried a sign, and it had a name on it.

My name.

Harrison George.

Yes, my parents had named me after a Beatle. Inadvertently, apparently. And backward. Stalin didn’t seem amused.

Next to him lay a canvas duffle bag with airline tags. I recognized it as mine.

I didn’t recognize him.

“I’m Harrison.”

“Ah. Mister Harrison. Your parents, they are, ah, detained. They send regrets. I am driver from Embassy. Sasha.”

The way he said the word detained sounded slightly ominous. And the fact that I couldn’t see his mouth under the mustache unnerved me.

I peered around him, still hoping to see her somewhere beyond. He misinterpreted.

“Nothing wrong, Mister Harrison. They are working late, is all. Come, I have bag. Davai. We go for car.”

He lifted my duffle, and I followed him past the baggage carousel as it spit suitcases out of a metal turret like an armored tank.

Nothing wrong. A warning bell rang inside my head in a moment of lucidity — or paranoia. I had no way to know who this man really was.

Maybe the likeness to a former Soviet dictator was no coincidence. Maybe the KGB recruited for that. Maybe my parents were somewhere else in the airport, checking their watches, inquiring after me.

I saw myself thrown into the trunk of a dark sedan, bound and gagged, bruised against the spare tire as my “driver” weaved and swerved through the chaos of Moscow traffic, before I was dumped into a basement deep inside the infamous Lubyanka Prison, left there for hours with the taste of rope in my mouth, mesmerized by the swinging back and forth of a light on the ceiling, until finally placed before a line of faceless men who hissed unintelligible interrogatories at me.

I’d seen Lubyanka Prison before from a car window and scoffed at the dreaded KGB headquarters, thinking myself bold, confident I had nothing to fear from its imposing facade. I was the son of U.S. diplomats. What could they do to me?

Now, following this stranger who carried my bag, I asked myself that question again. What could they do?

I thought I’d been safe. I’d laughed. Who’d be laughing now?

Leninsky Prospekt

Sasha approached the final set of sliding doors, and I followed him. In a minute we’d be outside.

The airport, unpleasant as it was, operated according to international standards. I’d spent my life in airports. I knew the rules. But between Sheremetyevo and the sanctuary of home, a great void waited to swallow me up.

I slowed down and broke into a cold sweat. Something had to give. My knees? My will? I could still turn back. I could search for the mysterious, beautiful woman. Maybe she hadn’t left yet.

Or maybe she was right outside.

That single solitary hope propelled me onward. I darted through the doors after Sasha. A bitter wind slapped my face. Reaching the curb, I scanned the sea of parked cars. Beyond them lay a desolate countryside. But no sign of the Mystery Woman.

Dejected, I caught up with Sasha. In a few minutes, we arrived at a black sedan with red and white license plates, emblazoned with the letters CD. Core diplomatique.

He offered me the back seat, not the trunk.

I sighed and reminded myself that if Americans were safe anywhere in the world, at any point in history, it had to be here in Moscow, during the Cold War. Too many sweaty fingers hovering over too many big red buttons in too many nuclear missile silos. The last thing anybody wanted was an international incident.

I took one last look at Sheremetyevo Airport and climbed in.

The highway from the airport took us through barren terrain, a wasteland dotted by the occasional cottage, until we hit the city. At that point, tall buildings sprang up like rockets on launchpads.

I considered Sasha. He'd turned out to be social, even charming. I wasn’t in a mood to make small talk, but I felt guilty for comparing him to Stalin. He asked if I played chess, like my mother. Or knew the poetry of Pushkin like she did. Yes, and no. He praised her knowledge of Russian literature and opera. He didn’t mention my father, who was well liked at the Embassy but didn’t have the same enthusiasm for Slavic culture.

After all, she was the high-level officer who spoke Russian so fluently she could chat with a Russian Ph.D about any arcane topic. She analyzed Soviet behavior, wired sensitive cables to Washington, and engaged in delicate negotiations. He was attached to the U.S. Information Agency, which meant he was more interested in promoting American culture. His job was to make sure Soviet citizens could taste the twin blessings of capitalism and freedom — no easy task, given the walls between us. But he found ways, arranging cultural exchanges, celebrity visits, Voice of America radio broadcasts.

We finally turned off the highway onto Leninsky Prospekt, Moscow’s second broadest boulevard, now lit by streetlights. Sasha braked at the entrance to #83, and we entered a cul-de-sac between concrete towers, a guarded compound for apartments where only Westerners lived.

My home.

Sasha plunked my duffle onto the pavement as I trudged out of the car. He leaned against its side and produced a pack of cigarettes. American. Winstons.

“I wait few minutes here. You tell parents hello. I see you here again, or at Embassy.”

Lighter in hand, he saluted. I think he smiled beneath his mustache. He cupped his hand over his cigarette and stared into the far distance, possibly at the prospect of stars above the ever-present clouds.

Light poured through the mottled glass doors onto green tiles. To the left, another light emanated from a militsiya booth, although I couldn’t make out the sentry stationed inside. Ostensibly, he was there for our protection. We all knew what he was really doing.

At the moment, no doubt, logging my arrival.

The elevator bore me on its jerky ascent to the top. I rang the doorbell. The door flew open, and I was in my mother’s embrace. She hugged tighter than I remembered. She had on her work suit, so I guessed she’d just gotten home.

“How was the flight, honey? I am so sorry I couldn’t meet you. The Ambassador called me in as I was getting ready to head out for the airport. Are you hungry? Put your bag down, and let’s get you some dinner.”

I gave her a kiss back and followed her into the kitchen. She took a plate out of the fridge, sausages and cheese blinis with sour cream, and set it on the table with a glass of milk. I took a long swig. The smooth sensation of the milk running down my throat comforted me. I wiped the back of my hand across my mouth and watched her. The deep circles under her eyes suggested she’d been working even longer hours than usual.

“The flight was fine, Mom. Where’s Dad?”

“Oh, your father? Well, he’s out of town. Last-minute trip.”

“Oh yeah?”

“He’ll be back by Christmas.”

“Where’d he go?”

“A cultural exchange program. Bit of an emergency, I think.”

“An emergency? For a cultural exchange program?”

She looked everywhere but at me. All of a sudden, she seemed incredibly uncomfortable.

“Oh, honey, you know your father.”

“Somewhere far?”

“Not too far. Minsk.” She patted the table. “Now eat. Then talk to me. I want to hear everything.”

I knew she was holding something back, but I let it go. She probably had a good reason. So I finished the blinis, then filled her in. About the trip, about school, about teachers, grades, friends.

It was good to be home.

I ran out my stories and she ran out of questions, so we said good night. I wanted to shake the odd feeling I’d gotten from her awkward answers. My parents didn’t like to share the details of their work, so normally I didn’t push. We had an unspoken bargain. I didn’t want to break it.

I thought back to the flight from Frankfurt.

After I’d found my seat, the first thing I’d noticed about the man sitting next to me was the paperback on his knee — I didn’t catch the title, but I saw the name on the spine: Пушкинъ. Pushkin.

He nudged the cassette case on my tray table and leaned over to read the handwritten label. I’d taken off my headphones between tapes.

“You like the Beatles, eh?”

He spoke with a Russian accent, but his English was crisp, near perfect. I nodded.

“The Blue Album,” he said, identifying my cassette. He was a small man, with wisps of light brown hair. Not quite as old as my parents. He smelled like menthol aftershave, the kind men slap on out of habit. “Compilation of singles, 1967 to 1970. One can find this in East Germany, smuggled in from West Berlin. Not so easily in Russia. It is a shame, really. Some of my comrades are … well, overzealous in their disapproval of Western music.”

I knew rock music, with rare exceptions, was banned in the Soviet Union. The state deemed it a font of cultural corruption, a danger to the fabric of society. Young people had to be protected from the pied pipers of bourgeois capitalism. Giving in made you a hooligan, a drunk, a gang member. It made you “antisocial” — a crime of the highest order.

In practice, I knew, Soviet purity didn’t live up to the rhetoric. Russians found small ways to circumvent the diktat that governed their lives. Or a few did, anyway. Possibly the man next to me on the plane. He traveled. That would make it easier.

Something about him intrigued me. An unsteadiness radiated from his eyes, which was easy to miss, because at the same time, he exuded such warmth. He seemed a little sad.

Naturally, he was curious why an American boy was flying to Moscow alone. I told him my parents worked at the U.S. Embassy, but he didn’t pry further. Instead, we talked about the Beatles for the rest of the flight. Favorite songs. Favorite albums. Stories we’d heard. He knew a lot, was eager to share and eager to know more. I bragged about the time I saw a show by a tribute band called Imagine, led by a cast member of the Broadway show Beatlemania. He lit up.

I didn’t get his name. After we landed, he nodded goodbye and melted into the crowd.

I went to my bedroom window. It framed a city in darkness, where no stars twinkled. Fourteen stories below, the militsiya booth sat on the ground like a tiny square Lego.

I fixed my gaze on it. I concentrated, willing the guard out of his station.

After a few minutes, the door flipped open. A woolly hat popped out and moved across the lot, covered with ice.

He crossed to the far side and stopped. Even from this distance, I could see the grim line of his jaw, the frayed threads of his belt, the thick padding on his boots. He hung his head for a moment, then shot his arms to the sky. Like a conductor in front of an orchestra.

Only I could see it. But this happened to me all the time. My imagination took over.

All around this side of Leninsky Prospekt, in dozens of neighboring apartment complexes, little doors opened in little guard booths with little dimpled roofs, and militsiya men, maybe a hundred, stepped out. They streamed toward mine, onto the icy lot. They took up positions in concentric semicircles facing him. His head was now bowed, his arms still appealing to the heavens. The first row kneeled, the second and third stood tall. There seemed to be a vibration in the air. Some were humming. Tuning their voices. A muted strumming followed, a lone balalaika.

The leader brought his arms down in a sudden crash as if striking kettle drums, and the voices rose in a great chorus, every last one singing into the night.

I recognized it, of course. It was the Beatles. “Back in the USSR.” Close to a hundred somber men belting it out, in harmony, like a hymn or an anthem. Like the country was free, its spirit unchained.

The clouds cleared away, and my choir filled the sky with song. The lyrics reverberated with joy down canyons between buildings to the city’s core, then came booming back off the Seven Sisters, Moscow’s massive, crowned skyscrapers.

My boundless euphoria projected itself for miles and miles, over a land where every inch seemed restricted, controlled, surveilled. That’s how my imagination worked. I had no control. No explanation. No warning.

The final strains of the chorus echoed and faded away. I wondered what the Beatles could mean to anyone here, where the state banned all forms of expression that questioned authority.

I dropped onto my bed and drifted into the mystical land of exhaustion-fueled dreams, where a figure hovered, enigmatic and arresting. She beckoned me with impossible visions.

Prudence

It took all morning for the jet lag to burn off. The aroma of fresh coffee came and went. By the time I rolled out of bed, the only sign of life in the apartment was a note on the kitchen counter. It’s what I’d expected.

Good morning, honey. Prudence called. She wants you to meet her at school. She said bring music. Sounds urgent. Love, Mom.

So that afternoon, I found myself staring into the empty yard of a Russian high school through wrought iron bars tipped with spikes.

Pru’s school was tucked a couple of blocks off a main boulevard behind a double row of apartment buildings. Dirty snowbanks muffled the sound of traffic, permitting faint clatters but no other noise. Hardly anyone lingered nearby.

A chorus of bells and cheers brought the schoolyard to life. The school’s double doors burst open, and navy-blue uniformed kids streamed out in twos and threes. They swung their buckle-strapped satchels, called out to each other. Girls held hands. Boys draped their arms over each other’s shoulders. Most were blond or sandy haired.

One girl stood out for her black curls and light brown skin. She walked alone.

My friend, Prudence Akobo.

She headed straight for a huddle of boys and a girl who crouched at the corner. One by one they opened their satchels and peered inside. A boy shoved Pru by the shoulder. She shrugged and showed her empty palms. Then she raised her head, looked around expectantly, and spied me.

A grin spread across her face, and I waved. She spoke to the others like she was hushing them, then launched toward me like a runner at a starting gun.

As soon as she got to the fence she grabbed the bars, bringing our faces inches apart. Her cheeks were flushed.

“Did you bring a tape?”

“What? Oh. The music. I forgot. What’s going on?”

“No time. What’s in your Walkman?”

She knew I carried it with me everywhere. I pulled it out of my coat pocket, popped it open, and extracted the cassette. It felt light, insubstantial. A black-and-gold TDK SA-X C90. I’d scrawled three words on the label late one night in my dorm room, its plastic still warm from the deck after an hour and a half of dubbing.

I held it up for Pru to see.

The White Album.

Officially, the record was eponymously titled The Beatles, a double album released in the band’s waning days at the end of the sixties. The minimalistic and monochromatic design of its sleeve had inspired the nickname.

“Perfect. Give it here, quick.”

“What for?”

“I’m trading.”

“Wait, so I won’t get it back? No way.”

“I made a promise. If I don’t deliver, I’m in trouble.”

“The tape’s not even good,” I argued, knowing it didn’t matter. “It’s messed up. It cuts out in the middle of ‘Revolution 9.’”

It was true. Both discs of the double album hadn’t fit onto the cassette. John and Yoko’s avant-garde piece, the penultimate track, stopped halfway. I had to leave Ringo’s moving lullaby, “Good Night,” off entirely.

But I couldn’t part with any of my tapes, especially not this one. The subzero windchill of winter in Moscow had made its own promise: to keep me cooped up for the whole break, with time on my hands and nothing to do. I would need my music.

“That won’t matter to anyone here,” she said. “Come on, you can dub all the Beatles albums you want when you get back to school. But they’re gold here.”

And illegal, I thought.

A couple of kids stopped to ogle my bright yellow Walkman, still in my hand. It stood out anywhere I took it, but here, in the wintertime, my tape player shone like the sun in a place that rarely saw either.

I didn’t want to disappoint Pru. And I didn’t want to make life any harder for her — Soviet school was hard enough. I shoved the tape through the fence into her waiting hands.

“Thanks. Give me a minute. Oh, and Harrison?”

“Yeah?”

“Welcome back!”

She ran back to her schoolmates. The girl and one of the boys stole furtive glances around the yard. They whispered and gestured. They swapped objects. One was my tape. The other, Pru dropped in her satchel.

A voice boomed across the yard. A straight-backed woman approached, her brow in knots. Pru’s coterie scattered, and she ran toward me. The teacher followed, singling her out, and sent a string of angry Cyrillic letters streaming through the air with her shouts.

Pru stopped at the fence. “Catch.” Her satchel flew up and over, landing in my arms.

“Pru, take the gate.”

“It’s still locked. Watch out.”

She grabbed the iron bars, set a foot against the bricks at their base, and leaped over sideways, barely clearing the spikes. As she flew, her coat opened and her shirt swept up, exposing the side of her torso and a black and blue mark, not from the spikes. More like she’d been kicked or punched.

When she landed, I stood there with my jaw hanging, holding out the satchel. She grabbed it.

“Time to go!”

As Pru sprinted off, I turned to follow, still stunned, and I rammed up against what I thought at first was a lamppost. A lamppost wearing an overcoat. I found myself staring into a rough face with eyes like gravel and a blade for a nose. The man grunted, then turned his attention to the school.

After a few blocks, Pru slowed down.

“You made it out of your cozy apartment, through the mean streets, in one piece. I’m impressed.”

“Ha ha. I know my way around the Metro. I can read the signs.”

“But you don’t always know what they mean.”

“I know enough.”

I took pride in the bits of Russian I did have — basic phrases, place names, key words for getting around. I remembered the alphabet from years ago when, as a little kid, on my parents’ first assignment to Moscow, I’d had a Russian nanny. A diplomatic tour of duty lasted two or three years. Sometimes I wished I knew the language better, but I’d known even then that if I made an effort to learn more, I’d only be whisked off to another corner of the globe where I couldn't use it.

“Sure you do. How was the flight?”

Pru knew I’d slept in. Her phone message had been a challenge, to see if she could get me up and moving.

“Fine. You’ve got a nasty bruise. What happened?”

“It’s nothing. Let’s go to Uncle Sam’s. I could use some hot food.”

“It doesn’t look like nothing. Did you get into a fight?"

“C’mon, I haven’t been to Uncle Sam’s since the summer, with you.”

“So now I’m your meal ticket too.”

She nudged my shoulder, smiling.

“Alberto’s french fries are the best remedy for jet lag. You know it.”

I didn’t need convincing. Every plate of fries that came out of Alberto’s kitchen was a hot, crispy, golden oasis. Actually, an oasis inside an oasis. Uncle Sam’s was the watering hole at the U.S. Embassy, a refuge of comfort food for Americans who longed for home, and open to guests from friendly nations. In another life, Alberto could’ve been the chef at a fancy restaurant in Rome. But he'd married a Russian he met in Italy and followed her back to Moscow, untethering himself from his native land two decades ago. And here, his art with the fryer won him accolades and affection.

“You’ll have to change out of the uniform first.”

Like all the other girls, Pru wore a blue skirt and white blouse with an oversized collar. She untied the red kerchief, her only colorful item, and stuffed it in her bag.

“Right. I don’t want to show up dressed like the enemy. Your Marines would throw a fit. We’ll stop at my place.”

Pru lived in a walled complex of shabby buildings nicknamed Sad Sam, for its location on Sadovo-Samotechnaya, the Garden Ring Road, which circled the downtown. It housed members of the foreign press and their offices. Both her parents wrote for newspapers, always distant from their native lands. Her father had left Ethiopia as a young man to study in Paris and stayed there. Her mother grew up in a small town in Ontario. She became a journalist out of wanderlust.

The two met in a crowded café in Prague on the day Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968. Beatles music played over the speakers. They fell under each other’s spell to the clatter of coffee cups, the chatter of intellectuals, and the crooning voices of John, Paul, George, and Ringo. The occupying troops forced them out of the country, but not before they each filed front page stories for their respective papers, hers Canadian, his French: SOVIET TANKS CRUSH PRAGUE SPRING. LES ARMÉES RUSSE ONT ENVAHI LA TCHÉCOSLOVAQUIE.

A few months later, they found each other again in another café, this time in Paris, and the brand-new Beatles song “Dear Prudence” was on the radio. Not long after, they got married. When their daughter was born, they’d known exactly what to name her.

With my parents, on the other hand, it never occurred to them that by calling me Harrison, they’d inverted the name of a Beatle. But it had been the first thing Pru said to me when we met the previous year, at a dinner party hosted by a mutual friend of our parents. She told me the story of her name, then we talked about the Beatles for the rest of the party and ignored everyone else. We bonded over the music we both loved. Our friendship grew, natural and easy.

Pru thought the world of her parents. I thought they didn’t pay her enough attention. I knew she hid a lot from them.

Like the bruise.

“My parents have important jobs,” she’d say. “They don’t need more problems.”

I couldn’t argue with that. Western reporters in Moscow lived their lives on tiptoes. They navigated a thicket without diplomatic safeguards. They had to protect their sources and avoid treachery. The Soviets had recently expelled an American reporter, calling him a spy.

I asked Pru if she knew him.

“Of course. He wasn’t a spy. The Soviets were retaliating, after Americans arrested a Russian in Washington.”

“Do you worry about your parents?”

“Never,” she said. “They’re indomitable.”

So was Pru.

She spoke Russian fluently, with an edge, spitting the words like you jab a penknife. She moved around the city like she’d lived there all her life, not just a few years.

“You should worry,” she retorted. “Yourmamancould be CIA. Easily. According to the Soviets, your embassy’s humming with spies who pretend to be diplomats.”

“What do they know? Anyway, my mom loves Russian culture too much. She wouldn’t do that.”

“KGB, then. A mole.”

“Yeah, right. Does my mother look like a spy? She’s as likely as your parents.”

With me, Pru let her guard down. Hanging out at Uncle Sam’s or stretched out on the shag carpet in my living room, watching a projected movie on a roll-down screen, the tough girl disappeared. She teased me for being soft, naive, dreamy. That might’ve been true, but I think she liked me all the more for it.

Halfway to the Metro, we ran into a couple more girls in school uniforms who talked to Pru animatedly in Russian. They sounded friendly, but I didn’t understand much, so my attention wandered.

We’d walked as far as the Ring Road, a broad avenue with literally sixteen lanes, but we were still a few blocks away from Sad Sam. Stark modern facades alternated with antique structures. A thousand windows, all with their own secret worlds. As I drifted away from Pru and her schoolmates, the glass panes in a building across the street blinked on like television screens, like music videos blasting scandalous pictures and sounds onto an unsuspecting populace. They blinked off again.

That’s when I saw her standing there. Below my imagined screens, like she’d stepped out of the brightest one.

She would have stood out anywhere. Paris, London, New York. Left them all behind.

This time, I saw her feet touch the ground. But I didn’t believe it. She still defied gravity.

The Mystery Woman

Once again, I couldn’t tear myself away. Even though an uncanny fear crept into my mind that by watching her, I invited trouble. Like she was tethered to a cloud of danger. But I couldn’t help myself.

“She’s stunning.” Pru had finished with the girls and joined me at the curb. “And a little scary. Do you know her?”

“Yeah. I mean no. I saw her at the airport. They gave her special treatment, so she’s important.”

“I can see you think so, lover boy. She does look important, though. Let’s follow her. See where she goes.”

Pru dashed away before I could say no. She crossed the street through a gap between cars, forgetting our plans. I had no choice but to follow. I didn’t shout out in case it would attract the Mystery Woman’s attention. Pru was twenty feet behind her when I caught up, matching the Mystery Woman’s pace.

Following so close, I felt like a magnet had me in its field.

“This is insane. What are we doing? What about Alberto’s fries?”

“Alberto can wait. We can figure out what’s so special about her. You obviously want to know.”

She said it with an edge. A challenge — another challenge. It was always that way with Pru. But there was more to it, and I wondered now how long she’d been standing there in silence as I’d watched.

A flurry of pedestrians blew across our path at a street crossing. Little cars weaved around them. A Metro station stood across the way, and for a second I lost sight of the Mystery Woman.

The hiss of a train beckoned from below ground.

I turned, then pointed at the steps descending to the Metro and said, “There she is.” Her sable hat bobbed in a sea of heads.

This time, I was the one who raced ahead. Pru caught up, and we let the concrete swallow us whole.

All the times I’d ridden the Moscow Metro, my pulse never raced like it did now. The station, usually torpid with sleepwalking bodies, came alive. So did I. I noticed every block of polished stone, every ruddy face, every flying scarf. Like so many of Moscow’s Metro stations, it was a cavernous temple carved out of marble. An altar to the commuting working class.

Pru shoved her five kopeks into the turnstile. I paused to search my pockets for the coins I knew I had, but she got to it first and reached back to repeat her move for me.

Once through, I let loose and ran ahead, dodging and swerving. The station hummed and thundered. A train rumbled in. The chain of cars rattled to a stop, meaning we had moments before we lost the Mystery Woman. Pru was taller than me by an inch or two, and she used it, poking her head above the crowd. I focused on the train doors, all of which were about to slide open.

I think we saw her at the same time, three cars down. Too many people in the way.

We made it past the first car and, with a second to spare, scooted inside the second one, behind hers. The car filled fast. I pushed back against the oncoming force of bodies squeezing us on all sides. We couldn’t see her now, but if we kept to the window, we might be able to see her exit.

The train jerked into motion, and we swayed with the masses. The confined space smelled of damp cloth and sweat.

Pru grinned at me. “It’s an adventure, eh?”

I allowed a tight smile. Adventure? I hadn’t chosen it. Or had I?

I’d come with Pru, after all.

Adventures could happen by choice or by chance. But I still had doubts about this one. I tried to think of a way out, a way to convince Pru to change her mind and head for Uncle Sam’s instead.

“Don’t you have homework to do?”

It was weak, I know.

“It’s all memorization. I’m good at that. I’ll do it tomorrow before class. Besides, you got pretty excited back there, lover boy. You want to know more about her, who she is. Don’t deny it.”

“Stop calling me that. But fine. I am curious. There’s something, I don’t know —”

“In the way she moves?”

I turned away. Pru’s allusion to the Beatles’ tune “Something,” one of the most beautiful songs ever written, was unfair. She noticed, and softened her tone.

“You’re right, though. She carries herself like she runs the Politburo. Maybe she’s on her way to an official ceremony. Or a covert meeting. Or she could be going to an illicit rendezvous. You might have competition!”

I blushed.

I had to stay positive. Pru’s mocking hadn’t gotten serious yet. She hadn’t told me I was too young for the Mystery Woman.

I shifted my focus to the Metro map above the window. We were riding the Circle Line, heading counterclockwise around the city. The train pulled into the next station, then the next. Each time, we stretched to catch glimpses of the car ahead. We passed the stop for the Embassy, and I thought about those golden fries. I wondered if Pru thought about them too.

Still, the Mystery Woman hadn’t gotten off.

Had we missed her? The flow of passengers made it difficult to see through the crowd.

Finally, the train stopped at Park Kultury station, and we spotted her leaving.

We followed her out, losing ourselves in the rush as much as we could without losing her. When she looked to the side, I saw she still wore the indelible smirk. Either it was the only expression she ever wore, or she was in the final stage of her plans for world domination. She changed tracks and boarded a Sokolnicheskaya train outbound. Once again, we made it into the car behind hers.

It surprised me that the Mystery Woman had to take the Metro anywhere. I would’ve expected someone like her to be chauffeured around in a Chaika, or even a ZIL, the limo reserved for the highest officials.

I checked my watch and realized that before long, it would be dark. We hurtled away from home, away from the Embassy, away from the safety of the known and familiar in a city where anything momentous, I feared, happened in secret places. Anxious thoughts welled up in my head.

“Okay, Pru, you’ve had your fun. We’re heading out of downtown now. Who knows where she’s going. Actually, maybe she’s going home. What do you want to do when she gets there? Knock on her door and invite yourself in? I haven’t been in Moscow a full day yet, and already I’m gonna be late for dinner.”

She ignored me. I tried another tactic.

“All right, I admit it, she’s kind of beautiful. But I’m done now. Let’s head back.”

“Fine. You’re way too young for her, anyway. We can get off at the next stop and turn around.”

I licked my lips, to taste the victory. All I got was chapped skin.

We disembarked at Leninskiye Gory, the one station in Moscow that was above ground. Actually, above water. It sat on Luzhniki Bridge, over the Moskva River, between the Olympic Stadium on the near bank and Lenin Hills on the far.

This platform contrasted sharply with the grander stations we’d left behind. No marble, just water-damaged concrete and rusted steel, all corrosion and decay. People said the structure had been close to collapsing from the moment it was built, decades ago now.

I was taking the first step onto the stairs to change tracks when Pru grabbed my shoulder.

The Mystery Woman had gotten off too. She was heading down the opposite stairs, leading outside, onto the opposite bank of the Moskva.

Then I saw a second figure, lurking at a pillar not far behind.

“Pru, that man in the overcoat, he was at your school. Outside the yard.”

“Are you sure?”

“I bumped into him. He followed us, he must have. But look, he’s watching her now.”

“Good. He can take over.”

“I’m serious. It’s the same guy.”

“Why would —”

“I think she’s in trouble.”

“What?” She snickered. “Are you saying you want to keep going?”

“Yes, I want to keep going.”

The Overcoat

Icouldn’t believe I’d said it. The urge rose up from a strange place, like I had no control. Like my daydreams. Like two worlds collided — the one inside my head, and the real one out there.

The man — the Overcoat — didn’t wait long. Once he reached the bottom of the steps, we followed.

The station emptied onto an embankment between the river and the hills. We weren’t the only pedestrians. Scattered couples milled about, admiring the skyline. Pru grabbed my jacket and led me along the railing. I understood. We had to mimic the couples, keep our distance.

The Mystery Woman walked for a short stretch, then stopped to face the river. She stood in contemplation, like she was letting her thoughts drift with the current. Her stalker, just ahead of us, stopped too. We waited.

I’d never shadowed anyone before. I wondered if Pru had. Maybe it came naturally to her.

The sun hung low over the horizon, hazy and indistinct. The sky resembled a dim lampshade so it was hard to tell. But I knew it was getting late.

Thick groves of trees rose gently up the hillside, and a path broke through them from the embankment. We watched the Mystery Woman disappear into the wooded terrain. Above and beyond, at the top of Lenin Hills, loomed the gargantuan central tower of Moscow State University, piercing the sky.

We looked at each other. That was her destination. And the Overcoat’s.

The trail through the trees wasn’t empty, so we could follow without being too obvious. And the leafless branches meant we could see ahead, so we wouldn’t lose them. But it also meant that either one could turn at any moment and see the incongruous pair of teenagers at their heels, the black girl wearing a Soviet school uniform and the white boy wearing an L.L. Bean parka.

On a different day, I could’ve admired a quiet hike away from the inner city to the top of Lenin Hills, one of the prettiest spots in Moscow. The scent of pine. The crunch of fresh snow. But today, the trees stood in clumps like spears at the ready, and the crunch of my feet on the snow roared in my ears.

Pru, on the other hand, walked lightly, with determination. She was happy.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)