6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

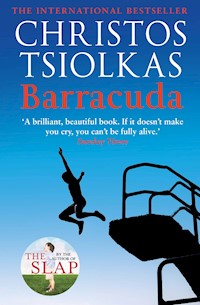

He loses everything. In front of everyone. Where does he go from here? Barracuda is the blazingly brilliant new novel from the author of the phenomenal bestseller The Slap. Daniel Kelly, a talented young swimmer, has one chance to escape his working-class upbringing. His astonishing ability in the pool should drive him to fame and fortune, as well as his revenge on the rich boys at the private school to which he has won a sports scholarship. Everything Danny has ever done, every sacrifice his family has ever made, has been in pursuit of his dream. But when he melts down at his first big international championship and comes only fifth, he begins to destroy everything he has fought for and turn on everyone around him. Tender and savage, Barracuda is a novel about dreams and disillusionment, friendship and family. As Daniel Kelly loses everything, he learns what it means to be a good person - and what it takes to become one. REVIEW "Tsiolkas writes with compelling clarity about the primal stuff that drives us all: the love and hate and fear of failure... A brilliant, beautiful book. If it doesn't make you cry, you can't be fully alive." (Sunday Times) "I finished Barracuda on a high: moved, elated, immersed... This is the work of a superb writer who has completely mastered his craft but lost nothing of his fiery spirit in so doing. It is a big achievement." (Guardian) "Terrific ." (Kate Saunders, The Times) "Masterful, addictive, clear-eyed storytelling about the real business of life: winning and losing." (Viv Groskop, Red Online) "This involving and substantial tale - surprisingly tender for all its sweary shock-value - is carried swiftly along by Tsiolkas's athletic, often lyrical prose." Daily Mail "The Slap, Christos Tsiolkas's bestselling previous novel declared 'Welcome to Australia in the early 21st century.' The same semi-ironic sentiment echoes throughout Barracuda, which is, if anything, an even greater novel... It may tell an old, old story, but it has rarely been told in a better way." (Sunday Telegraph) "Christos Tsiolkas is in his natural element, with sentences gliding elegantly until the reader is utterly submerged in this absorbing story." (Metro) "This is a compelling, moving novel about identity, failure and the redemptive power of family" (Mail on Sunday) Acclaim for The Slap: "A cool, calm, irresistible masterpiece." (Chris Cleave) "The Slap is nothing short of a tour de force." (Colm Tóibín) "Honestly, one of the three or four truly great novels of the new millennium." (John Boyne) "Now and then a book comes along that defines a summer. This year that book is The Slap."Daily Telegraph "As addictive as the best soap opera." Daily Mail See Christos talk about Barracuda http://atlantic-books.co.uk/barracuda

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

barracuda

First published in Australia in 2013 by Allen & Unwin.

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christos Tsiolkas, 2013

The moral right of Christos Tsiolkas to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders.

The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 178239 377 1Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 242 2E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 419 8Export e-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 243 9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

And now tell it to me

in other words,

says the stuffed owl

to the fly

which, with a buzz,

is trying with its head

to break through the window-pane.

—The Best Room, or Interpretation of a Poem,Miroslav Holub

For Angela Savage

Contents

Part One

First week of term, February 1994

Friday, 8 April 1994

26–27 July 1996

Labour Day Weekend, March 1997

Australian Swimming Championships, Brisbane, 20–23 May 1997

Fukuoka, Japan, August 1997

Friday 28 August 1998

Friday 15 September 2000

Part Two

Easter 2003

Australia Day, 2006

Thursday 24 June 2010

Winter Solstice 2012

Acknowledgements

Note on the Author

part one

BREATHING IN

WHEN THE RAIN FIRST SPILLS from those egg-white foams of cloud that seem too delicate to have burst forth in such a deluge, I freeze. The heavy drops fizz on the dry grass as they hit; I think this is what a pit of snakes would sound like. And suddenly the rain is falling in sheets, though the sky is still blue, the sun still shining. The Glaswegians on the pebbled shore are yelling and screaming, rushing out of the water, huddling under the trees, running back to their cars. Except for the chubby young man with the St Andrews tattoo on his bicep, criss-crossed white lines on blue; he is standing in the water up to his knees, grinning, his arms outstretched, welcoming the rain, daring it.

And just as suddenly the rain has stopped and they all slink back to the beach. Two young boys race past me and throw themselves into the lake. A teenage girl throws away the magazine she has been sheltering beneath, takes out a compact and starts to powder her cheeks and nose, to reapply colour to her lips till they are the pink of fairy floss. Someone has turned the music back on and the words when love takes over roar through the valley. A pale skinny youth with broken teeth and a mop of greasy black hair dives past me; sheets of crystal-clear water splash all over the wading tattooed guy, who grabs his friend, holds him from behind in a bear hug, and ducks him under. He sits on him, laughing. A woman shouts from the shore, ‘Get off him, Colm, get off him!’

The chubby guy stands up, grinning, and the thin boy scrambles to his feet, coughing water.

The girls and the women are all in bikinis, the boys and the men are all in shorts, and bare-chested or in singlets. Except me: I have jeans on and two layers on top, a t-shirt and an old yellowing shirt. The sun feels weak to me; it can’t get any stronger than pleasant, it can’t build to fire, it can’t manage force.

•

‘Dan, I can’t go back there. I can’t. Everything is too far away.’

Clyde’s words have been going around and around in my head all day. Too far away.

In the restaurant the night before, we were eavesdropping on a nearby table: a group of friends—three couples, one Scottish, one English, one German. They were in their late fifties, the men all with beards and bellies, the two British women with newly acquired bobs, the German woman with her grey hair pulled back in a long, untidy ponytail. She had looked up when we first started arguing, when I first raised my voice.

‘And I can’t live here.’

‘Why?’

‘Because this, for me, is too far away.’

We glared at each other across the table. One of us had to submit. One of us had to win. The young waiter arrived with our mains and we attacked them in viscous silence.

The group seemed to be old university friends, their lively conversation and loud laughter an invasion. The sauce on my steak was all salt and thick melted butter. I tore into it, was the first to finish. I pushed back the plate and headed off to the loos. Behind me I could hear the argument from their table. It seemed they got together every two years, in a different city. The German woman was pushing for it to be Barcelona next time, the Scottish man thought it should be Copenhagen and the English man wanted it to be in London.

When I returned we were both stiff with one another, miming politeness.

‘They took a vote, it’s a tie between Barcelona and Copenhagen.’

‘Really? Even the English guy voted against London?’

‘Aye, even he realised what a fucken stupid idea that was.’

That made us laugh, the lovers’ shared complicit laugh, a peace flag. I looked across and the German woman tilted her shoulders, smiling at me and feigning exasperation.

‘Barcelona,’ I called to them, ‘I’d make it Barcelona—the food will be better.’

The Englishman patted his big belly. ‘We don’t need more good food. We’ve had enough!’

We were all laughing then.

Clyde leaned in to me. ‘We couldn’t do that if we went back to Australia.’

I didn’t answer. It was true, and my silence confirmed it.

‘It’s too far away, Dan, I cannot go back.’

It was true. I had lost.

And then the words came from deep within me, were said without my forcing them, they just came like curses. I whispered them: ‘And, mate, I can’t stay here.’

That night, in bed, he told me he didn’t want my skin next to his, that he couldn’t bear my touch, and I obediently moved to the edge of the bed. But soon I felt him moving closer, and then his arms wrapped over mine, binding me to him. All night he held me, and all night he couldn’t stop his crying.

•

The chubby guy’s neck and shoulders and face are sunburnt. All the Glaswegians, sunbathing, paddling, strolling, kissing, eating, drinking on the shores of Loch Lomond, all of them have pink shoulders and pink faces and pink necks and arms. There is one Indian family eating Tesco sandwiches on the shore, and one black girl I noticed back in the village, she was with her red-haired boyfriend looking into the windows of the Scots R’Us shop or whatever the fuck it is called. And then there is me. Even with this piss-weak sun, I have gone brown. If I stay here will my colouring eventually fade away from me? Will I go pale, will I too turn pink in the sun?

The chubby guy is still only in water up to his knees. His mates dive in, they put their heads under, they splash and they play and they float. But they don’t swim. None of these people swims. No one ventures further than a few metres from the shore. But there is nothing to fear here, no sharks, no stingers, no rips, no dumping waves that can strike you down like a titan’s fist. There is nothing to fear in this water at all. Except the cold. There’s always the cold.

I am at the shoreline. The waves can’t muster any energy, the waves lap gently across pebble and stone. They push at my sneakers, they kiss the hem of my jeans.

I am taking off my shoes and I am taking off my socks.

Real water punishes you, real water you have to work at to possess, to tame. Real water can kill you.

And I am taking off my shirt, I am taking off my t-shirt.

Men and women have died in this loch, men and women have frozen in the water, men and women have been claimed by this loch. Water can kill you and water can be treacherous. Water can deceive you.

I feel a twitch in my shoulder, I can sense that the muscles there are stirring.

And I unbuckle my belt, I take off my trousers.

The chubby guy is looking at me, puzzled, his expression turning into a grimace. He is thinking, Who is this bawbag, this pervert, stripped to his Y-fronts on the shore? A girl behind me is starting to titter.

I am walking into the water, to my thighs, to my crotch, to my belly. It is cold cold cold and I think my legs will snap with the pain of it. I dive. Breath is stolen from me.

Muscles that haven’t moved in years, muscles that have been in abeyance, they are singing now.

And I am swimming.

I can’t hear them back on land but I know what they’re shouting. What are ya doin’, what are ya doin’, ya mad bastard?

I am in water. It is bending for me, shifting for me. It is welcoming me.

I am swimming.

I belong here.

First week of term, February 1994

The first piece of advice the Coach ever gave Danny was not about swimming: not about his strokes, not about his breathing, not about how he could improve his dive or his turns. All of that would come later. He would never forget that first piece of advice.

The squad had just finished training and Danny was standing shivering off to one side. The other guys all knew each other; they had been destined to be friends from the time they were embryos in their mothers’ wombs, when their fathers had entered their names on the list to attend Cunts College. Danny kept repeating the words over and over in his head: Cunts College Cunts College Cunts College. The nickname he and Demet had invented when he first told her he had to change schools. ‘Have to or want to?’ He’d had to turn away as he answered, ‘It’ll make me a better swimmer.’ ‘They’ll all be rich,’ she countered. ‘You know that, don’t you, only the filthy rich go to Cunts College?’ But she left it at that. She wasn’t going to argue with him, not about the swimming; she knew what the swimming meant to him.

Danny glanced at the other boys. They had hardly said a word to him all morning, just offered grunts, barely nodded to him. It had been like this all week. He felt both invisible and that there was nowhere for him to hide. Only in the water did he feel like himself. Only in the water did he feel that he could escape them.

Taylor, the one they all followed, made towards the change rooms and as he passed Danny, he said in a loud effeminate lisp, ‘Dino, I like your bathers, mate, they’re real cool.’

The others cracked up, turning around to look at him, to look down at his loose synthetic bathers, cackling like a pack of cartoon hyenas. They were all wearing shiny new Speedos, the brand name marked in yellow across their arses. Danny’s swimmers were from Forges—there was no way his mum was going to spend half a day’s pay on a piece of lycra. And good on her. Good on her, but he still felt like shit. The boys continued sniggering as they passed by him, all following after that pompous dickhead Taylor. Scooter, who was the oldest, the one with the palest skin but the darkest hair, Scooter bumped him. Just a touch, just enough of a nudge so it could seem like an accident. ‘Sorry,’ Scooter said abruptly, and then laughed. That set them all off again. The same stupid cackling. Danny knew it was no accident. He stood there, not moving, nothing showing on his face. But inside, inside he was coiled, inside he was boiling.

‘Eh, Scooter, you’ve got nothing to laugh about, mate. You weren’t swimming today—that was fucking paddling.’

That silenced them. The Coach was the only one who could get away with swearing at them. Even Principal Canning pretended not to hear when Frank Torma let fly with his curses and insults. The school needed Coach Torma. He was one of the best swim coaches in the state, had coached Cunts College to first in every school sports meet of the last seven years. That was power. They immediately shut up and continued to the showers. Danny went to follow them.

‘Kelly, you stay behind. I want to talk to you.’

The Coach was silent until the other boys had disappeared into the change rooms. He looked Danny in the eyes for the first time. ‘Why do you take it?’

‘What?’

‘Why do you take their shit?’

You could hear his accent in the way he pronounced the word, ‘chit’.

Danny shrugged. ‘Dunno.’

‘Son, always answer back when you receive an insult. Do it straight away. Even if there’s a chance there was nothing behind it, take back control, answer them back. An insult is an attack. You must counter it. You understand?’

One side of Danny’s mouth started to twitch. He thought the Coach must be joking; he sounded like Demet’s mother or Sava’s giagia, as if an insult were the ‘evil eye’, as if he needed to wear a nazar boncuğu to ward against it. Danny’s jaw slackened, his head slumped back. He was not even aware of it, he had just assumed the pose; that was how you reacted to instruction back at his old school, the real school: you just looked bored when an adult was giving you a lecture.

But Frank Torma’s expression remained serious and Danny realised this wasn’t a joke.

‘Listen, you stupid boy, if there is no spite, no hate or jealousy in what they say, then it does not matter. Nothing is lost.’ The Coach patted his enormous stomach, the huge gut hard and round like a basketball straining his t-shirt. He was pointing to something beyond his gut, something inside, but Danny didn’t know what that could be. ‘Trust your instincts, son, don’t let them poison you. You have to protect yourself.’ He pointed towards the change rooms. ‘They’re all jealous of you.’

‘That’s bullshit.’

For a moment Danny thought the man was going to hit him: the Coach’s right hand danced, spun, jerked in the air. Instead his fat finger drilled hard into Danny’s chest. ‘Listen to me, they’re jealous of you—of course they are. You have the potential to be the best in the squad. The others can sense it.’ The Coach’s finger was now pushing harder. ‘They’re going to want to get under your skin, and they’re right to. You are not friends, you are competitors.’

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!