8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

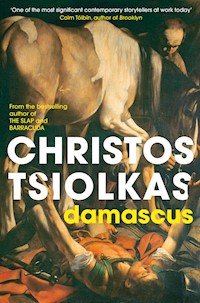

'We are despised, yet we grow. We are tortured and crucified and yet we flourish. We are hated and still we multiply. Why is that? You must wonder, how is it we survive?' In a far corner of the Roman Empire, a radical sect is growing. Alone, unloved and battling his sexuality, Saul scrapes together a living exposing these nascent Christians, but on the road to Damascus, everything changes. Saul - now Paul - becomes drawn into this new religion and its mysterious leader, whose crucifixion leaves followers waiting in limbo for his promised return. As factions splinter and competition to create the definitive version of Christ's life grows violent, he begins to question his new faith and the man at its heart. Damascus is an unflinching dissection of doubt, faith, tyranny, revolution, cruelty and sacrifice. A vivid and visceral novel with perennial concerns, it is a masterpiece of imagination and transformation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR

The Slap

‘Once in a while a novel comes along that reminds me why I love to read: The Slap is such a book . . . Tsiolkas throws open the window on society, picks apart its flaws, embraces its contradictions and recognises its beauty, all the time asking the reader, Whose side are you on? Honestly, one of the three or four truly great novels of the new millennium.’ John Boyne, author of The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas

‘The Slap is nothing short of a tour de force, and it confirms Christos Tsiolkas’s reputation as one of the most significant contemporary storytellers at work today . . . Here is a novel of immense power and scope.’ Colm Toíbín, author of Brooklyn

‘Brilliant, beautiful, shockingly lucid and real, this is a novel as big as life built from small, secret, closely observed beats of the human heart. A cool, calm, irresistible masterpiece.’ Chris Cleave, author of The Other Hand

‘A novel of great emotional complexity; as the narrative unfolds, it becomes clear that Tsiolkas has a rare ability to inhabit his characters’ inner worlds. The Slap places family life under the microscope, and the outcome is nothing less than a modern masterpiece.’ The Times

‘The Book of the Summer. Now and again a book comes along that defines a summer. This year that book is The Slap . . . The Slap has one elusive, rare quality: it appeals to both genders . . . The ideal summer read: escapist, funny and clever writing by a brilliant Australian novelist.’ Telegraph

‘. . . a “way we live now” novel . . . riveting from beginning to end.’ Jane Smiley, Guardian

PRAISE FOR

Barracuda

‘Tsiolkas writes with compelling clarity about the primal stuff that drives us all: the love and hate and fear of failure. He is also brilliant on the nuances of relationships. Some of the scenes in this novel about the hurt human beings inflict on each other are so painful that they chill the blood. At times, the prose is near to poetry.’ Sunday Times

‘By page 70 I realised that I was reading something epic and supremely accomplished. Thereafter, I found myself more and more admiring of the subtle, profoundly human way that Tsiolkas was handling his subject. And I finished Barracuda on a high: moved, elated, immersed . . . This is the work of a superb writer who has completely mastered his craft but lost nothing of his fiery spirit in so doing. It is a big achievement.’ Guardian

‘This involving and substantial tale – surprisingly tender for all its sweary shock-value – is carried swiftly along by Tsiolkas’s athletic, often lyrical prose.’ Daily Mail

‘Masterful, addictive, clear-eyed storytelling about the real business of life: winning and losing.’ Viv Groskop, Red Online

‘The Slap, Christos Tsiolkas’s bestselling previous novel, declared “Welcome to Australia in the early 21st century.” The same semi-ironic sentiment echoes throughout Barracuda, which is, if anything, an even greater novel . . . It may tell an old, old story, but it has rarely been told in a better way.’ Telegraph

First published in Australia in 2019 by Allen & Unwin.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Christos Tsiolkas, 2019

The moral right of Christos Tsiolkas to be identified as the author ofthis work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Map by Wayne van der Stelt.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 021 7E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 023 1

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Malcolm Knox, with gratitude

‘. . . for he who always hopes for the best becomesold, deceived by life, and he who is always preparedfor the worst becomes old prematurely; but he whohas faith, retains eternal youth.’

Fear and Trembling, Søren Kierkegaard

Saul I

35 ANNO DOMINI

‘Where were you when I laid the foundation of theearth? Tell me, if you have understanding.’

—THE BOOK OF JOB

The world is in darkness. The hood the guards have placed over her head scratches at her cheeks and neck. She takes fleeting comfort from the smell of the greasy fibre, the odours of sheep and goat. From her first memory their bleating was part of her life. They were her companions during the day and over countless nights, when she’d join them in their rough stable to escape the drunken violence of her father and her brothers, and then that of her husband. The warm bodies of the goats had been her solace and her bed; they had been her work and her friends.

She also recognises another smell, far more noxious. Fear. How many others has this hood covered? The stink of their terror is soaked through the fibres. With every hoarse breath she too releases the acrid taint of fear. She must not let them know her dread. She prays. Our Lord is a shepherd, He is not a king or a priest or a master, our Lord is a shepherd. With every silent repetition of that prayer, the demon that is fear subsides. She falls into calmness.

The rope that binds the caul is loosened and a tremor of light battles with the darkness. The hood is snatched off her and the overwhelming sunlight burns her eyes. The world is white: blinding, terrifying white. At first there is only that brilliance of light. Then she discerns the shadows. And as those shadows take form she sees that she is in the centre of a circle. Surrounding her are bearded men, each one holding a rock. As her eyes adjust to the day, she can see the sun flaring off the wall of the Sacred City in the distance. Then she sees crows and vultures wheeling above her. They are in a gully—it is accursed ground. And with that thought, fear reclaims her. On this ground she will die. Piss runs down her legs, darkens her smock, streams onto the stony ground. Her hands are still tied behind her back so she cannot cover her shame. She drops to a crouch.

One of the men marches up to her and roughly grabs her shoulder, forcing her to stand. His nails dig through the cloth and bite into her flesh. But this pain she can endure. She stares at the man; he’s a youth, not much older than she is. His eyes are dark and pitiless. She knows those eyes, knows such contempt. He wants her to scream, to curse, he wants her to hate him. And she wishes she could curse, could strike him dead with her words. Then she remembers the shocking and unbearable commandment of the prophet. Love him. Love him as if he were of your blood. She shudders, she leans forward, her lips graze his cheek.

‘Whore!’ He strikes her with such force that she sprawls across the dusty ground. She sees him marching towards her, she sees his foot lift. She closes her eyes, bracing for the kick.

‘Enough.’ The priest’s command is sharp. She dares open her eyes. The man has returned to his place.

She struggles, falters, wavers to her feet. This time she sees an old man and a boy standing beyond the circle in the shade of a laurel. From the splashes of dye across their cheeks she recognises them as deathworkers. They will return her body to the earth when her soul ascends to the Lord. A little beyond them stands the man who tricked her. How gentle his questions had been; his sympathy almost womanly. She fixes her gaze on him, his broad forehead, the receding coils of his black hair. He looks away as soon as her eyes meet his. Fear. She sees that he too is filled with fear.

The young man who struck her has raised his arm, stone held high above his head.

‘Adulteress!’ he roars. ‘Ask the Lord to pardon your wicked sins!’

The circle of men rumble assent. At the meanness of that charge, she begins to weep. Her eyes turn again to the man who’d seduced her with his false kindness. She had believed him to be as she was, bonded to the Saviour, trusting in the marriage of their fellowship, understanding that she was now married to her brothers and sisters. He had nodded in fierce agreement, as if he too comprehended that real marriage wasn’t the ugly, forced rutting she had experienced with her husband. After discovering friendship, knowing kindness, awaking for the first time to a world in which men need not be cruel, how could she return to that vileness? And he had nodded and agreed. She had been drawn to his sympathy. Yet it had been his testimony which had condemned her.

Her innocence and anger fortify her. She is no whore and she has not betrayed the Lord. She faces her accuser. He will not look at her. Her mouth is dry but she must speak. She doesn’t care about the other men in the circle. She wants that coward to hear her words.

‘If you are without sin, then cast your stone.’

One of the men steps forward. ‘Shut your ungodly mouth!’

She spins to face the speaker and as she does the first rock smashes her shoulder. She stumbles and falls. A rock slams into her neck, it steals her breath. Another rips open her brow. And then she hears the crack of the world splitting, as if the heavens above are tearing. There is darkness. There is blood in her mouth. There is a pain so terrible that she knows it is not the world that is breaking but her own body.

And then the darkness lifts and there is light.

The men keep hurling the rocks but the girl is dead and so justice is done.

The priest hurries through the prayers, conscious of the pulsating heat of the rising sun and the black swarm of flies already descending on the pariah’s body. The white prison shawl is dark with blood. As he intones the last word, the men quickly bend to drag their hands along the ground, rubbing the grit across knuckles, fingers, palm and wrist, beginning their purification.

The priest turns towards the south gate of the city and the men follow him. Not one of them looks at the bowed man, hunched on his knees, his head and body twitching in furious prayer.

Saul looks up only when he can no longer hear their footsteps. He calls a final invocation to the righteous Lord. He forces himself to look at the body of the dead girl. The old deathworker has dragged his cart up to the corpse, calling for his apprentice. The boy jumps to attention, peels off his tunic and skirt, then wraps the cloth around his mouth and nostrils. Naked, he rolls the girl over. A splinter of shattered jawbone has pierced her chin and the split gash is the pink of meat laid on a butcher’s trestle. Saul leans forward and retches.

The old man looks at him, then strips. Every bone is visible through the scarred membrane of his aged skin. Years of poverty have sculpted him into the very form of hunger. He too bends over the body.

Saul wipes the bile from his lips and chin. ‘Don’t bother searching her,’ he calls out. ‘She had nothing.’

The old man pokes at the body, not in the habit of believing anyone. Then, with a shrug, he nods to the boy. The boy stands and turns to Saul.

‘Uncle, what was her crime?’ He is Arab, both in tongue and in the shock of the hood of flesh that collects and covers the head of his sex.

‘She denied the Lord,’ Saul answers in Syrian, ‘the Lord of her people. She abandoned her family. She had to be punished for her blasphemy.’

At this, the old man snorts. ‘She was just a chick of a girl—what does she know of blasphemy?’

He wipes his nose and rubs his hand across his straggle of chest hairs. His next words are a sneer: ‘Did you hunt her down? Was she one of yours?’

As if Saul were a filthy mercenary, a slave trader, a collector of tax for the dirty Romans.

A thousand curses are on his lips. Shut your foul mouth, you Arab piece of shit. Child of a whore. But no sound comes forth. His head is heavy, the light is banished and the curses are snatched from his lips. The din is a madness in his head, and he has to cover his mouth to keep the words from escaping: If you are without sin, then cast your stone. Brazen, unholy words; the devil’s words. He knew those words were for him, that she was judging him. As if he were the one who stood condemned.

‘Are you ill, uncle?’ The naked boy is before him, his hand raised, seemingly about to touch Saul.

He jerks away from the filthy deathworker. ‘Do your foul work,’ he spits at him. ‘You’ve been paid.’

Saul turns from them, abandons the judgement ground, and climbs up the hill, thistles scratching across his calves. He can hear the vile old Stranger laughing; he hears the thud as the girl’s corpse is thrown onto the cart.

Someone calls out after him; the torrent of violence in his head is such he can’t discern if it is the apprentice or the old man.

‘Do we bury her or do we burn the cunt?’

To earth or to fire, the girl is lost to the Lord. He does not reply.

Death’s breath is on his skin; he can smell it. The blood and meat and sin and poison of the girl. He wants to be careful not to touch anyone, lest he stain them with his pollution, but the market-sellers have set up their tables and the streets are full of people and slaves, beggars and labourers, scavenging dogs and bleating goats. Saul keeps close to the walls, ducks into narrow passages to avoid contact. In this way, slowly, he weaves through the back streets and manages to avoid the crowds. He breathes deeply with relief. He has reached the wide marble steps leading to the Temple. The mansion of the Lord reaches up to the heavens, the smooth face of the rock glistens from the touch of the sun. He smells incense and burning wood; wisps of smoke curl around him. He unties his sandals, delivers his prayer and enters the bathing pool.

He washes death off himself.

Finally, rocking back and forth on his knees, he begs the Lord, the One, the only One, to cleanse him and forgive him.

I am not a filthy child killer.

Cleansed, he passes through the first gate of the Temple and enters the courtyard. They have sent Ethan, a novice priest, to pay him. And even that young cur won’t look at him—there’s disdain in the way he drops the coins into Saul’s palm. As if to touch Saul were an abomination. I am not a filthy child killer. He wishes he could grab the young man’s throat, slam him against the walls, deliver blow after blow until the supercilious fool pled for mercy. He has heard the little shit take classes in the Temple, stumbling over the words of the prophets, forgetting the sacred text. It is he, Saul, who should be teaching the young men, it should be Saul promised to priesthood. Every sacred word is carved across Saul’s heart. Every single word of the Lord. But Saul was born to toil, unlike this pampered and sneering child.

He needs the four meagre coins in his curled fist. The skinning season has not yet begun and there is a cycle of the moon to be completed before he can return to Tarsus, to his brother’s farm, and begin his work of preparing hides to stitch into tents and canvases. This is the life Saul was born to.

‘Sir,’ and the word fills Saul’s mouth with bitterness, ‘do you need any tutors?’

Ethan has turned away. ‘No. We don’t need you this season.’

Saul groans as he descends the Temple’s steps. How dare he believe himself worthy of priesthood? Though silently, he cursed in the Lord’s house. He could wash and scrub at his skin for years and he would never be washed clean.

As soon as he enters his sister’s house, Saul intuits danger. He stoops through the doorway and an ill-feeling knocks against his chest and heart, as if a malevolent force were in the room. He brings a prayer to his lips but even before he can recite the words, his sister rushes at him out of the darkness, her fists banging against his chest. He knows that not even prayer will still Channah when she’s in such fury. Her curses are not words, they are the shrieks and wails of the monster that has possessed her. Her fingers claw his cheek and the violence brings him to his senses. He hits her.

He sees his brother-in-law, Ebron, rise from his seat by the hearth and go over to his fallen wife. ‘You deserve that.’

Channah curls her veil over her face but the cloth cannot mask her sobbing.

Saul nods at Ebron and goes to where his nephew, Gabriel, is sitting. The youth jumps to his feet, embraces his uncle. The boy’s arms are as steadying and peace-giving as a prayer. Saul inhales the youth’s scent: toil and strength, salt and earth.

He turns to his sister. ‘Forgive me, Channi.’

Even muffled, her words can be heard. ‘May the Lord grant me death.’

Ebron, furious at her for inviting evil into his home with those words, slaps at her head.

Saul turns to his nephew. ‘What has happened?’

‘They have arrested Jacob.’

At this Channah stirs, unwinding her veil. ‘And now they will arrest you,’ she seethes. From the ground, her burning eyes then fix on Saul. ‘All this begins with you, brother. You are the oldest—you are our father, and you have abandoned all responsibility. That’s the root of all this evil.’

She spits on the ground. ‘Unmarried, unfertile. You are no man.’

A great weariness falls on Saul. It is the cloak of iron that he must wear, the heaviness that cannot be shed. Ebron has raised his arm again but Saul clicks his tongue—an almost imperceptible sound, but it is enough to stay Ebron’s hand.

‘What have they arrested your friend for?’

Gabriel shrugs, makes no answer.

‘It will be for sedition,’ says Ebron quietly.

At the word, Channah starts moaning.

Turning his back to his sister, Saul beckons the men to come close. ‘Tell me what you know.’

The boy lifts his shoulders, his eyes returning to the flickering embers of the hearth. ‘I know he had with him a message from our brothers in the Stranger’s city.’

At this his father snorts. ‘May the Lord shit on Caesarea. Nothing but evil comes out of that stench-hole.’

Saul takes his nephew’s chin, forces the boy to face him. ‘Please tell me that there was no letter. Tell me that he had memorised the message from your comrades.’

Gabriel does not answer.

His father strikes at his son. ‘You play at being warriors,’ he snarls. ‘You emulate and crawl after those arse-fucked Zealots but you are not men, you are just boys. And ignorant children at that. It’s no wonder that the Romans eat us alive.’ He spits into the fire. ‘Your friend has probably already betrayed you.’

Channah wails.

Saul turns to his nephew. ‘Tomorrow we will have to leave for Tarsus. You will stay at your uncle Samuel’s house and he’ll find you work as a labourer until the skinning season starts. Then we can work together. In Tarsus you’ll be safe.’

Gabriel begins to protest but Saul cuts him off. He knows what he has to do. He is not the helpless eunuch his sister believes him to be. He will save this boy; he will not allow the Romans to take him.

‘You have no choice in this matter, son,’ says Saul. ‘You will stay with your uncle and I will ask him to find you a bride.’ He grabs the boy by his nape, brings his face close. ‘Your father is right; you are no warrior.’

It is a mistake. The boy struggles, breaks free and leaps to his feet. ‘How dare you speak of right and wrong? You who do the Council’s bidding, who hunts fellow Jews for those depraved priests? They’re not our rightful priests—they’re lackeys of the false king and of the Strangers.’

The youth’s eyes burn with his mother’s lethal fire. And like hers, his voice is filled with scorn. ‘You hunted a girl for them, didn’t you? We’ve heard. She was a child and still they stoned her. How do you know what makes a warrior? You’re a lackey to lackeys. My mother is right: you are not a man. We don’t need your counsel and we don’t need your filthy blood money.’

Saul can’t answer. His nephew’s words have wound tight around his heart. Shame is burning into him. He loves this boy as a son. How often has he dreamed of Ebron’s death, so he could truly be father to Gabriel? Reprehensible thoughts, but he cannot stop dreaming them: this is how much he loves the boy. But the boy detests him, as does their world; can think of him only with revulsion.

Saul cannot move, he cannot speak. But Ebron is on his feet and has grabbed his son by the hair, cuffed him and thrown him against the wall. The dazed boy drops to the ground and his father stands over him.

Ebron’s voice is cold, sure, allowing no dissent. ‘You little turds think you’re better Jews than we are because you’ve been schooled in words. I may be an ignorant worker but I know that one of the eternal commandments is to obey your parents and elders.’

He shoots a look at Saul. ‘Isn’t that right, brother?’

He doesn’t wait for Saul’s answer. And Saul has no spirit with which to answer.

The father, shaking, drops to his knees beside his son.

‘Boy, my boy, I am sorry to have hurt you. But you don’t have the ruthlessness to be a fighter. I know you—I’ve raised you. That little whore they stoned, she insulted the Lord—she left her husband and her children. Your uncle did her a mercy to denounce her.’

Ebron strokes his son’s face. ‘You say you hate the Strangers, that you want to expunge them from our lands. Have you got your uncle’s courage? Can you put a knife to the throats of the bastards the Roman soldiers are breeding in the whorehouses behind their camp? Can you hold a blade to an infant’s neck and cut it?’ He kisses his son. ‘That is the kind of warrior we need, my son, my sweet boy. Can you do that?’

The boy coughs, spits blood. But his hand tightens around his father’s arm. Trying to steady his breathing, struggling to form words, he finally says, ‘I will do as you say.’

Not as I say, thinks Saul, never as I say. I will never be his true father. You are not a man. The truth of these words slam into him. They are right: he has no son, he has no home; as he is constantly travelling between Jerusalem and Tarsus, he is always in the keep of his sister and his brothers. He is pitiful; he creates nothing. What an absurd vanity to hope that he could ever earn Gabriel’s respect.

Saul gets to his feet, a storm in his head and a violent trembling in his body. He must flee this house. He stumbles to the door but his sister grabs at him. She kisses his hands, thanking him, praising him, forgiving him. The four winds roar in his head as he searches his tunic, finds the coins, lets them fall to the dirt where they belong—the evidence of his sin and his unmanning. But even as he does so he knows he has kept back two pieces of the thin metal, cold against his heart. The darkness has been expelled from the house but as he pushes through the door, he understands that the darkness is in him, that it comes from deep within himself.

The wine is new in the barrel, sweet, thin and potent. Between his second and third drink the tavern fills with market workers. He finds himself sitting with Barak, a fellow tentmaker. The man is a bore, always whining about being cheated. But coddled by the warmth of the tavern and the heat of the wine, Saul is content to listen to the man’s complaints.

He feels a breeze as the thick hide over the doorway is pulled aside and another trader enters. It is dark outside. When did it become night? In the courtyard, servants and labourers are squatting on the ground, drunk and squabbling.

‘We must eat.’ Saul goes to get up, to shout to the tavern owner, but he cannot stand and falls back onto the bench. Barak laughs out of his toothless black mouth and calls out for olives, for chickpeas and pickled figs, for oil and bread.

A young servant boy, half his face carved away by pox, brings the dishes.

Saul grabs at the figs in vinegar, stuffs the soft fruits into his mouth; they ooze over his chin and fingers. He uses a piece of bread to wipe off the sticky juice and burps in satisfaction. ‘Another wine?’

Barak’s eyes narrow. ‘Are you buying?’

You cheap goat. Saul fingers the two coins underneath his tunic. One coin will pay for two more drinks. He will not waste the second. He gets to his feet and this time he remains upright.

‘More wine,’ he calls out.

The boy comes and pours the wine, then stands back as the two men raise their cups. There is something in the servant lad’s scowl: disdain, almost judgement.

‘Do I know you?’

The boy starts and moves away.

Barak blinks, snorts, and leans into Saul. ‘He belongs to the Nazarene’s sect.’ He winks. ‘He’s probably terrified that you’ll have him be stoned.’

‘If I could,’ Saul growls, ‘I’d stone the whole diseased mob of them.’

Barak gently taps his knuckles against Saul’s temple. ‘All that learning of yours is useless, Saul. Your parents were under a wicked curse when they were convinced to send you to school.’

He gestures towards the boy, who is serving another table. ‘That one believes that the Lord sent us a saviour who got arse-fucked by the Romans before they nailed him to a crucifix.’ He spits after that accursed word. ‘Concentrate on your work. Why waste your time on such madness?’

Saul straightens, not wanting to slur his next words. ‘I do it for the Lord, I do it for our people. The madness of that sect undermines us—their madness is what keeps us slaves to Rome.’

Barak grabs Saul around the neck, holding him close, glancing quickly around the room. He whispers, his breath hot in Saul’s ear, ‘You do it for the coin, friend. And you should learn to keep your mouth shut in a public place.’

Saul pulls away. But he is chastened. The room is crowded, ringing with noise. Even so, he knows he shouldn’t have spoken so loudly or so recklessly.

‘You are right,’ he confesses to his friend. ‘I’ve drunk too much—I’ve got to go.’

Barak has a grip on his arm. ‘Marry, friend, raise a son. That is the first and the wisest law of the Lord. Mind your trade and forget the nonsense the priests have infected you with.’

Saul pulls away. He stumbles, knocking against a bench. One of the men seated there shoves him hard and Saul lands face first on the dirt floor. He clambers to his feet. The whole tavern is laughing at him. It burns. He finds his way to the door and as he pulls back the hide, the servant boy is there, returning from feeding the louts outside. The man and the boy stare at each other.

‘Who’s your father?’

The boy, shocked, frightened, does not open his mouth.

‘Who’s your father, boy?’

One of the drunks in the alley calls out, ‘He wouldn’t know.’

The laughter, now louder, is a roar.

And Saul laughs too. ‘A bastard, hey? Just like your Yeshua of Nazareth. They say his father was a Roman soldier. Is that right?’

Fury, hatred and loathing flash in the boy’s round dark eyes. And danger. But then, as if those evils have been lifted from him, the boy’s eyes are smiling. He slides his fingers down one cheek, as if removing phlegm from it.

‘Sir,’ he says humbly, ‘I need to work.’

Pushing the boy aside, Saul steps out into night, the rage collected in his fists. First, to snap that boy’s spine; and then to shatter the whole world.

Marry, raise a son; his words to his nephew have returned as a curse. The wine swills in his body, poisoning his thoughts and his stride as he bashes through shrub and thickets of nettles. Marry, raise a son. It is a new, weak moon, and there is no light, only darting and disquieting shadows. He is not carried by will, his feet are leading him; he has no thought except to stay upright, to not slip and break his neck as he makes his way into the steep valley. Marry, raise a son. Will he never escape those words? He is nothing but shame, lower than a beast. That whining fool Barak was right: he isn’t even capable of fulfilling the Lord’s first and greatest commandment. He has no son, no heir and no purpose. He kicks at stones on the path, feels the warm wind against his cheek and naked chest; his smock has fallen off one shoulder. He clutches at the cloth, feels for the coin.

None of them, not his family, his friends—none of them know the depravity of his yearnings. He has no will, all is simply movement, leading him inexorably to corruption. How can anything that comes from him not be poisoned? How can any issue of his not be damned? He has no will, he is only the sum of his lusts. At a bend he trips and falls flat on the ground. The pain brings tears. He twists, tests his foot. Nothing is broken, he can stand. He looks up to the sky and a black cloud glides over the heavens, revealing the slender curved slice of the moon. The Strangers bow and beg to her, believing that she is a goddess who can illuminate their souls. They make offerings to her and they claim she answers their prayers. What if he were to drop back to his knees, what if he were to offer himself to her? Here, on this very spot, outside the Lord’s city itself, the silhouette of the Lord’s house clearly evident? Would the goddess rid him of the fear that winds its coils around him whenever he is near a woman? Would she make him whole, give him a wife and a son? He spits to the moon; he spits at her—at the idiocy of the Strangers. Pray to the moon, pray to the hearth, pray to the eagle, pray to the goat, pray to the fire, pray to the wind, pray to the sea, pray to the sun. A thousand gods, a thousand dumb and blind idols. He is as broken as Job, but yet his Lord loves him. A thousand idols and a thousand kingdoms have come and gone, only Israel stands immortal.

Love for the Lord has conquered time. He has climbed to the top of the ridge; he is descending into the second valley. Before him are the fires of the Roman camp. He can smell the wine and he can smell their sins. He can smell the lust. That is why his feet have brought him here. Saul raises a hand, claws at his cheek, is satisfied only when he senses the warm blood. He is no Job, he is not a good man, he is vileness and sin, his will is lust.

Guarding the wooden gate that opens to the brothel tents, two young Roman soldiers are flicking pebbles into the air, seeing which can send theirs the highest. Saul, his head clear now, marvels again at the Strangers’ fascination with games, with the foolish trickery of sorcerers. This is a new people, thinks Saul, a young people, and they have the manners and pursuits of children. And the cruelty of children. They crush kingdoms as if they were insects.

At his approach the soldiers stand alert.

He bows. ‘May I pass?’

The younger soldier, long-jawed and thick-lipped, points the hilt of his sword to a mound of rocks by the gate. Ash from incense covers the flat headstone. There are offerings before the idol—twigs and torn cloth, petals and a broken reed flute.

‘Do what you must do,’ the soldier orders.

The young idiot speaks a terrible Greek.

Saul answers clearly. ‘I am a Judean, sir.’

The youth’s eyes glare.

They hate us as much as we hate them, thinks Saul.

But the soldiers move aside and let him pass.

He hears their laughter, he hears one say to the other, deliberately in Greek so Saul will understand, ‘I pity the poor whore who has to suck on his ugly cut cock.’

Saul’s cheeks burn with disgust and shame. And from hate; the hate outweighs the shame and makes him forget his disgust. May he live to see the day that the Strangers are routed, the heads of the soldiers lopped, but not before they suffer violation, skull crushed against skull and bowels slit open.

Saul stamps on the heads and hearts and loins of Strangers as he weaves down the path to the fires, the illicit camp, where men sit on their haunches, waiting, peering into the darkness of the tents. The sputtering lamplight within casts grotesque shadows against the canvas, spectres that writhe and twist. They reach out for him, serpents from the depths of Hades seeking to possess him. His righteous hatred is gone, strangled by the shadow hands and ghost vipers that graze his skin, coil around his head and whisper in his ears, a cold reptilian hand that has slid between the folds of his robe and settled on his sex. And he is possessed by the loathsome beast, inflamed by it: his putrid sex is hard. He squats in the line, covering his depravity.

All around him, he sees his fellow sinners in the ravenous queue seeking the oblivion of fornication, the stench so palpable that it releases fumes: he can see the smoky vapours wisping off his skin and twisting up into the hideous night. He more than any of them, he stinks of lust. And yet knowing all this, he is too fearful to raise a prayer. He must not foul the words of the Lord by uttering them in such a place; and even though he knows the depths of his disgrace, he cannot rise and run, cannot leave these abominations behind: his betraying flesh will not let him.

Saul peers over the heads of the men in front of him to look into the tent. A hairy arse, more goat than man, rises and falls in thrusting convulsions. The whore beneath him is hidden by the vileness of the exertion; whether a boy or a girl or a boy-girl, it is not possible to tell. The thrusting beast moans and collapses with a final stab. The whore rolls out from under him; she grabs a cloth, wipes feverishly at her naked flesh. The man stumbles through the flap of the tent, wiping at his wet loins, covering his shame. Already another has approached from the front of the line. A naked boy leaps from the shadows holding a copper dish. The wind rises in the valley, intensifying the flickering light coming from a lantern in the tent and revealing the boy’s heavily kohled eyelids. Near the bed a clay idol is suddenly visible: a squat, ugly form with seven flopping teats. The new man drops a coin into the dish, already pulling back his robe and dropping to his knees before the woman. In Greek she tells him to wait. She intones a prayer in Syrian and waves her hand over the idol, then lies back, opens her legs, and lets the man fall into her.

The rancid smell of sweat and corruption has the thickness of blood on Saul’s tongue and mouth. He is no longer of the Lord, no longer of Israel, no longer of his people or the world. He is bloodless, a demon. He is death. The boy whore is walking along the queue of customers. Hands reach out to grope his stubby sex, clutch at his thighs and buttocks. One of the hands presents a coin and the boy snatches it, pulls the bearded man from the line and takes him by the hand into the tent. The boy also stoops and rushes through a prayer to the idol; and then they fall back into the black depths of the tent, behind the fornicating couple. Again the shadows leap and dance, they torment and goad.

The line of men stir, impatient, their complaints indistinguishable from the moans of the rutters. The man sitting in front of Saul turns and offers him a wan smile. His face is boyish, his black beard still thin, yet corruption has begun its relentless desecration—Saul sees it in those sad hollow eyes. The lad is rubbing himself. Saul leans forward. To embrace him? To urge him to leave? To flee; to regain youth? Saul cannot move. The youth’s other hand has climbed Saul’s thigh, is scratching at Saul’s loins. Only then, his fingers tightening around Saul’s sex, does the youth look up again, a smile touching his lips.

Saul closes his eyes. The evil is within him and he is possessed; succumbing is a glorious release. That flare of pleasure is worth death, worth the everlasting silence of his Lord.

The youth has turned his back to the line, for discretion, and as skin brushes skin, the wicked odour of flesh, putrefying and decaying, fills Saul’s nostrils.

He comes to at the sound of anguished howling. The youth is lying kicking in the dirt—every time he tries to clutch his hand, the base hand that reached for Saul, he screams louder: one long finger dangles, broken at the joint. The men have abandoned the order of the queue and form a ring around the writhing boy. Saul finds himself standing over the screaming youth, his wrist throbbing with pain, such was the force with which he snapped the other’s fingers. One man pushes Saul, another yells, ‘Go on, finish off the dirty man-cunt.’ From her bed, and over the back of the sweating beast still thrusting into her, the whore unleashes furious oaths in Greek and Syrian. From the distant camp, a soldier yells out for silence, threatening slaughter to the filthy Judeans and Arabs.

Saul slips in the mud, so eager is he to flee.

A spirit emerges from the night. It reaches out to him. ‘Coin,’ it cries, in scavenger Greek. ‘Coin!’

He blinks and sees the condemned girl before him, unbroken, naked, the tiny mounds of her breasts, the puff of her emerging nipples. Her words in death split open his brow, storm into his head: If you are without sin, then cast your stone.

He cannot move. He is not in his body. He is with her, they are both soaring in their abandonment to death.

Again the squeal: ‘Coin, coin.’ Her small hands, the sharp blades of her long dirty fingernails, feed into his flesh. For the second time in this evil hour, he awakens. This girl is younger, darker, a Stranger. He fumbles under his tunic, finds the remaining coin, throws it to the ground. The girl falls upon it, a ravenous hound seeking meat. She grabs it and rushes to embrace Saul. He allows his arms to drop around her bony shoulders. Her hand reaches under the robes, finds him. He shudders, thrusts once, releases. The girl stoops and wipes him off her palm and into the dirt. Night then swallows her. Swallows him.

The sun slices his eyes. He blinks. His lips are toughened hide, his neck cannot support his head.

Channah is pouring water into a pot. ‘Wash,’ she orders. ‘Gabriel has already packed the mule.’

She comes and sits beside her brother. And then shocks him; she kisses him on the brow. ‘Oof,’ she cries, flapping her hand, ‘you still stink of wine.’

As he washes, he listens to her relating gossip shared at the well. He washes hands, feet and, turning from her so she can’t see, carefully washes his loins. He could wash for eternity and he would not be clean.

‘I thought you were the foul Strangers,’ she laughs. ‘When you smashed into the house in the middle of the night, I thought they had come to take our Gabriel.’

She raises his hand and kisses it. ‘Thank you, brother, thank you for saving him.’

As she prepares a breakfast of rye and milk, she continues her tales. ‘A group of Zealots attacked the Strangers’ camp last night,’ she whispers, so the children can’t overhear. ‘They went rampaging through the brothels, slitting the throats of the whores and their clients.’

Saul has no words.

‘The soldiers retaliated. They murdered those poor boys.’ She thumps a fist against her breastbone. ‘Those young rebels are deluded but the Lord is just and they died righteous getting rid of that Greek filth. Their descendants will be proud for generations. They will live forever.’

And I will expire with my last breath, thinks Saul. I have no heirs and I will not live. I don’t deserve to.

Saul is waiting patiently with the mule when his nephew returns from his ablutions at the sacred pool.

Gabriel kisses him on each cheek, a roguish grin on his face. ‘Are you suffering this morning, Uncle? Has the wine turned sour?’

‘Wine always turns sour,’ Saul answers gruffly.

The youth goes to take the reins but Saul won’t let him.

‘I can wait, Uncle, go and wash. I’ll wait till you return from the Temple.’

The older man shakes his head. ‘No, I have wasted enough time.’

Gabriel, shocked, begins to protest.

His uncle pulls tighter on the rein and the mule brays in protest. ‘Come on, let’s go. We’re not wasting any more of this morning.’

As Ebron kisses and farewells Gabriel, Saul hears him say in a hushed tone, ‘You must learn, son, to be cautious around a man being punished by wine.’

Channah is weeping, and cannot let go of Gabriel. The children too begin to wail.

‘Don’t cry,’ Gabriel says gently. ‘I’ll be back for Passover.’

Channah has taken her son’s hand and places in it a tiny, knotted garland of hyssop. Saul pretends not to see the unholy trinket.

His mother releases Gabriel. ‘Of course he’ll be back for Passover,’ she tells her younger children.

She kisses her son one last time. ‘With a wife,’ she adds, ‘the Lord be willing.’

As they begin the descent into the first valley, Gabriel keeps turning to look back at Jerusalem, at the glorious and commanding edifice of the magnificent Temple. Saul refuses to do so. He has no right. As they march past the judgement ground, he shudders, recalling the bloodied body of the stoned girl. Further on, they walk along the back wall of the Romans’ garrison, the brothel tents now collapsed and lying limp on the ground, spent grey ash all that remains of the fires.

Saul steps on a patch of darkened soil. Is it the wind? Is it the wind in the valley calling: Coin, coin? He sees a blade carve the night, sees the knife slash the throat of the beggar girl, sees her blood weeping into the earth. His nephew keeps looking back, mouthing prayers until the city of David disappears in the brilliant haze of the defiant sun. Not once does Saul turn. He knows it was not the Lord who’d saved him last night. The Lord had intended him to be there, to face the Zealot’s blade, to suffer the Lord’s justice. Those demons that have tainted his blood—the Greek spirits, the temptations of the Romans, the evil music of the Strangers—the demons gloat. They want to keep playing with him, because they know they own him. He is their servant. The Sacred City, his world, all that is wondrous and true and pure, it is forbidden to an accursed man such as Saul.

Hope

LYDIA, ANTIOCH57 A.D.

‘Do you believe in God, Momma?’

‘I don’t know—why doesn’t He help me?’

‘You’re supposed to praise Him whether you’re in pain or not.’

‘That’s unfair.’

‘Well, we’re not supposed to judge Him.’

‘I don’t want a God like that,’ she said.

‘If you believed what the Catholics believed, you could pray to the Virgin Mary.’

‘No woman made this world. I couldn’t pray to a woman.’

—HAROLD BRODKEY, ‘A STORY IN AN ALMOST CLASSICAL MODE’

I know what they call me. Witch. Sorceress. Hag. They fling their shit and they throw their stones and words.

But they cannot hurt me. My son, my brother, my Jesus, he is always with me, he is always beside me. The boys and the old shepherds, the slaves who collect firewood from this hilltop, they curse me, condemn me to Hades and to the obscene tortures of their callous gods. I wipe their shit from my cheeks, brush their dirt off my rags. Nothing they do can hurt me.

None of them dare to touch me, nor even to come close. The degradation of my work takes care of that. Their gods would demand a year-long ablution, their fathers would throw them out of their homes, their spouses banish them from their beds. The city gates would be closed to any who dared touch me. My corruption is absolute.

I need neither house nor company. On this dark side of the mountain, these bleak crags and desolate caves are the rooms I dwell in, and the sparse cypress canopies are all the shelter I need. In the storm seasons I have seen lightning dislodge a tree, cleave it from its roots and shoot it far into distant thickets. The noise is the thunder of the earth splitting. But no lightning has ever touched me. I have no fear. I gave up the world and in that surrender I was made brave. I was released from servitude and I was released from being a woman. The rocks and the trees are my home now. Beyond is the desert and behind me is the world. I have no need for it. I am no longer part of it.

‘Witch, witch!’ they scream, thinking the word will hurt me. I smile and I say, ‘Thank you.’ A stone grazes my cheek. I repeat, ‘Thank you.’ Shit spatters my lips. I wipe them, and again say, ‘Thank you.’

To this mountain they bring their children. On these ledges and in these caves they lay their newly born. Here they leave the blind child, the crippled child, the child born with a purple mark across its face. And here they abandon their girls. They light their offerings if they can afford them, and they chant their prayers to the Mother. Demeter, Isis, Al-at. We have virgins promised to you, Mother, may the next child born be a son. If they see me, they shriek and hiss. Witch. Sorceress. Hag. But they do not dare to come close. They abandon their infants and they flee.

I wait. Till their chanting can no longer be heard. Till their scents have been banished by the wind. Till I can no longer hear their footsteps. Then, only then, do I go to them. To the children they’ve abandoned.

This one has been born with no eyes. I kiss his brow. ‘Child, child,’ I whisper, ‘you I will name Fortitude.’ I tell him of a God who knows mercy and who loves justice. I tell him of a world to come that has a place for him. ‘It could even be tomorrow, child,’ I whisper. ‘Soon, very soon, he is returning.’ I go to the next infant. I kiss her belly, I lay my ear against her still-beating chest. I ask the wind and the birds to stop their songs. Faint is the beat of her heart but I can hear it. ‘You, child,’ I say softly, not to frighten her, ‘you, I will name Devotion. There is a God, child, who will make the last first and the first last. I promise you this, Devotion.’

Night. Dangerous night. I could choose to leave, I could choose to turn my eyes away, flee to the other side of the mountain, where the cypress trees grow taller, where shepherds have seeded bushes of thyme and a wild yellow garden of chamomile. I could sit there, look down at Antioch. If there is a ripe moon I could raise my finger and trace the shadow outline of the city’s walls. Or I could look beyond to the river, winding silver in the moonlight. I could cover my ears, make myself deaf to the wretched cries.

But I don’t. I stay to look. I stay to hear. As the wolf circles the crying infant, as it bares its teeth, growls and bites, as the infant offers one last cry, as the body becomes blood and meat. I crouch in the cave, hearing the slither of the snake, hearing the crunch of bone as the serpent’s jaws engulf the child. I do not look away; I stay, to be witness, to know what it is we do when we forsake our children, when we leave them on the mountainside. How can I bear witness to all of that and not be deranged? Because my son, my brother, my Jesus, he is with me, he is beside me. These are not my sobs, not my lamentations. They are his cries. This is his suffering.

In the mornings I build a fire. The meat that remains, the bones, the hair, the torn clothes that swaddled the infant, I gather and place in the fire. I watch them burn. I recite his words as I watch the fire grow and feed. I recite the words my teacher Paul first taught me. In the kingdom to come, the last will be first and the first will be last. All that remains is burned. But to the charred bones and ash I whisper, ‘This I promise you: the last will be first and the first will be last.’

I was not born a witch. I was born a woman. I was raised a Greek. When I first came to Antioch I said that I was born in Philippi, but my village lies over a day’s journey from there. My father’s blood is Macedonian and it is those mountains and those springs of pure water that are my true home.

My father was a brickmaker and it was to that trade that our family was bonded. All my brothers bake the clay. Of my mother’s clan I know nothing. My father’s first loyalty was to his ancestors and to his gods. Once she was married my mother forsook her allegiance to the spirits of her home and she never saw her family again.

‘You are my oldest daughter,’ she would whisper to me, cradling me so I might fall to sleep, ‘and it is you who are now my family and my life.’ She would quietly sing songs from her mountain home, her fingers weaving through my locks, her kiss on my brow. When she thought me asleep, she would gently unwrap her arms. ‘Don’t leave me!’ I would cry—I was terrified of the dark. ‘Don’t be silly, Lydia,’ she would say. ‘I will never leave you.’ With that promise I could sleep.

We all worked. I was the elder sister and as such the responsibility for my younger siblings fell to me. My father was stern and distant. He barely spoke to me. But he was generous to his two daughters and refused to have us work at the kilns. He was a hard worker, as was my oldest brother, Hercules—well named, for he was strong and fierce. All my brothers had to work. Every day was spent digging and then on the moulding of the clay: hard work—but the worst ordeal by far was working in the kilns. The ferocious heat that burst from them had scorched and prematurely lined their faces. In time my father’s dedication was rewarded by the gods, and he was able to hire two labourers to assist him and also to purchase three slaves. Two of them were men, who worked in the clay quarries and in the kilns. The third, Goodness, was a young maiden who helped us with the chores of the household.

Of all my tasks, the one I enjoyed most was attending to the altars. There were three of them in the house. The first and the grandest was the altar to the Mother just inside the gate that opened to our courtyard. It stood on a dais that my father had built from the first batch of bricks he had ever fired. He had kept them with him through his apprenticeship and into his marriage, through the building of our home, in order to make this dedication to the Goddess. Her form had been sculpted in clay by an artisan priestess bonded to the Great Mother’s temple. The second altar lay just before the hallway to the night chambers, and was dedicated to Hermes, to ensure that He would bring us dreams of peace and dreams of providence in the night, and not punish us with visions of furies and monsters. And the third altar was within my parent’s chamber, in honour of the god Priapus, a likeness of His sex, erect and thick, carved from wood that came from an ancient pine tree on my father’s home mountains.

Every morning, on rising, it was my duty to prepare a meal for each of the deities. The first offering was always to the Mother. Under instructions from the priestesses, my father had planted a pomegranate tree to shade the Goddess. And every morning I would stand under the tree and curse it on behalf of the Mother. The tree that had enslaved Her daughter was now slave to the Goddess. With the end of the winter, and with it the resolution of Her lamentations, I would take a budding fruit from the gnarled branches and bite into it. That hard, shiny skin was often resistant, but there was a blade by the altar that I could use to slice it open. I preferred, however, to bite into the pomegranate if I could, so that the scarlet juice would spurt over my chin and neck. ‘The red juice of the fruit is a blood offering,’ my mother instructed. ‘The Goddess is a woman and Her due is blood. Give the Goddess Her due and She will never abandon you.’ I would smear the pulp across my mouth and lips, and then I’d bow and kiss the brick on which She sat. Once that was done, I’d carefully scoop out six seeds and place them in front of Her. Then I would offer the meal and make my prayers. For Father, for Mother, for my brothers, for my sister, for our household, for our good fortune.