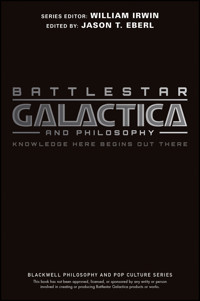

Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy E-Book

19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series

- Sprache: Englisch

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE "The contributors to Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy strive to make things relevant to fans of the show, and they put their information out in a way that is accessible to folks who wouldn't know Heidegger from Heineken." Green Man Review, Spring 2009 "The writers are well versed in their subjects...The book is most effective at making the reader rethink what they thought they knew." Neo-opsis What's the point of living after your world has been destroyed? This is one of many questions raised by the Sci-Fi Channel's critically acclaimed series Battlestar Galactica. More than just an action-packed "space opera," each episode offers a dramatic character study of the human survivors and their Cylon pursuers as they confront existential, moral, metaphysical, theological, and political crises. This volume addresses some of the key questions to which the Colonials won't find easy answers, even when they reach Earth: Are Cylons persons? Is Baltar's scientific worldview superior to Six's religious faith? Can Starbuck be free if she has a special destiny? Is it ethical to cut one's losses and leave people behind? Is collaboration with the enemy ever the right move? Is humanity a "flawed creation?" Should we share the Cylon goal of "transhumanism?" Is it really a big deal that Starbuck's a woman?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 459

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Giving Thanks to the Lords of Kobol

“There Are Those Who Believe...”

PART I OPENING THE ANCIENT SCROLLS: CLASSIC PHILOSOPHERS AS COLONIAL PROPHETS

1 How To Be Happy After the End of the World

The Good Life: Booze, Pills, Hot and Cold Running Interns?

“Be the Best Machines (and Humans) the Universe Has Ever Seen”

“Be Ready to Fight or You Dishonor the Reason Why We’re Here”

“Each of Us Plays a Role. Each Time a Different Role”

NOTES

2 When Machines Get Souls: Nietzsche on the Cylon Uprising

Master Morality and Slave Morality

Escaping Slavery by Creating Souls

The Spiritual Move from Slave to Equal

“They Have a Plan”

NOTES

3 “What a Strange Little Man”: Baltar the Tyrant?

“I Don’t Have to Listen. I’m the President”

“Are You Alive?”

NOTES

4 The Politics of Crisis:Machiavelli in the Colonial Fleet

“We’re in the Middle of a War, and You’re Taking Orders from a Schoolteacher?”

“While the Chain of Command is Strict, It is Not Heartless. And Neither Am I”

Helo’s Halo: Can Genocide Ever be Justified?

“It’s Not Enough to Survive. One Has to be Worthy of Surviving”

NOTES

PART II I, CYLON: ARE TOASTERS PEOPLE, TOO?

5 “And They Have A Plan”: Cylons As Persons

Cylons and the Capacity for Reason

Cylons and Mental States

Cylons and Language

Cylons and Social Relationships

Do We Have a Plan?

NOTES

6 “I’m Sharon, But I’m A Different Sharon”: The Identity of Cylons

“We Must Survive, and We Will Survive”—But How?

“Death Becomes a Learning Experience”

“I Am Sharon and That’s Part of What You Need to Understand”

“It’s Not Enough Just to Survive”—Or Is It?

NOTES

7 Embracing the “Children of Humanity”: How to Prevent the Next Cylon War

“A Holdover from the Cylon Wars”

The Resurrection Ship

The Limit on Cylon Intelligence

“The Cylons Send No One”

“The Shape of Things to Come”

NOTES

8 When the Non-Human Knows Its Own Death

“One Must Die to Know the Truth”

“Prayer to the Cloud of Unknowing”

Bored, as in Really Bored

The Boxing of D’Anna Biers

NOTES

PART III WORTHY OF SURVIVAL: MORAL ISSUES FOR COLONIALS AND CYLONS

9 The Search for Starbuck: The Needs of the Many vs. the Few

Should We Stay or Should We Go Now?

Frak the Numbers!

Saving Starbuck?

The Mark of Cain

“Evil Men in the Gardens of Paradise?”

Sacrifice

NOTES

10 Resistance vs. Collaboration on New Caprica: What Would You Do?

“A More Meaningful Impact”

“Desperate People Take Desperate Measures”

“An Extension of the Cylons’ Corporeal Authority”

“We’re Gonna Be There, Tyin’ the Knots, Makin’’em Tight”

“A New Day Requires New Thinking”

NOTES

11 Being Boomer: Identity, Alienation, and Evil

“Red, You’re an Evil Cylon”

“You Can’t Fight Destiny”—or Can You?

Manichaean “Sleeper Agents”

“A Broken Machine Who Thinks She’s Human”

Will the Real Boomer Please Stand Up?

“We Should Just Go Our Separate Ways”

NOTES

12 Cylons in the Original Position: Limits of Posthuman Justice

“How Is That Fair?

How Is That in Any Way Fair?”

“We Make Our Own Laws Now, Our Own Justice”

“The Shape of Things to Come?”

NOTES

PART IV THE ARROW, THE EYE, AND EARTH: THE SEARCH FOR A (DIVINE?) HOME

13 “I Am an Instrument of God”: Religious Belief, Atheism, and Meaning

“A Rational Universe Explained Through Rational Means”

“That Is Sin. That Is Evil. And You Are Evil”

“You Have a Gift, Kara... And I’m Not Gonna Let You Piss That Away”

“The Gods Shall Lift Those Who Lift Each Other”

“You Have to Believe in Something”

NOTES

14 God Against the Gods: Faith and the Exodus of the Twelve Colonies

“If This Is the Work of a Higher Power, Then They Have One Hell of a Sense of Humor”

“I Am God”

Giving Oneself Over to God

“Could There Be A Connection... ?”

NOTES

15 “A Story that is Told Again, and Again, and Again”: Recurrence, Providence, and Freedom

“We Are All Playing Our Parts”

“God Has a Plan for You, Gaius”

“Out of the Box Is Where I Live”

“It’s Time to Make Your Choice”

NOTES

16 Adama’s True Lie: Earth and the Problem of Knowledge

“You’re Right. There’s No Earth. It’s All a Legend”

“I’m Not a Cylon!... Maybe, But We Just Can’t Take That Chance”

“You Have to Have Something to Live For. Let it be Earth”

NOTES

PART V SAGITTARONS, CAPRICANS, AND GEMENESE: DIFFERENT WORLDS, DIFFERENT

17 Zen and the Art of Cylon Maintenance

“Life is a Testament to Pain”: Suffering, Ignorance, and Interdependent Arising

“All of This Has Happened Before...”: Karma and Rebirth

“God Has a Plan for You, Gaius”: Religion, God, and KenDsis

“How Could Anyone Fall in Love with a Toaster?” Cylons as Persons?

NOTES

18 “Let It Be Earth”: The Pragmatic Virtue of Hope

Peirce and Adama: Hopeful Pragmatism

James and Roslin: Religious Hope

Apollo and Tyrol: Social Hope

Hope vs. Fear

“A Flawed Creation”

NOTES

19 Is Starbuck a Woman?

Sarah Conly

What Is a Woman?

“I Am a Viper Pilot”

But Aren’t Men and Women Different?

Crossroads

NOTES

20 Gaius Baltar and the Transhuman Temptation

The Fall of Baltar

The Transhuman Temptation... Really!

The First and Last Temptations of Baltar

“There Must Be Some Way Out of Here”

NOTES

There Are Only Twenty-Two Cylon Contributors

The Fleet’s Manifest

The Blackwell Philosophy and PopCulture Series

Series editor William Irwin

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy helping of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life—and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching.

© 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

BLACKWELL PUBLISHING

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA

9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

The right of Jason T. Eberl to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks, or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

First published 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

1 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Battlestar Galactica and philosophy: knowledge here begins out there/edited by Jason T. Eberl.

p. cm. — (The Blackwell philosophy and popculture series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978–1–4051–7814–3 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Battlestar Galactica (Television program: 2003–) I. Eberl, Jason T.

PN1992.77.B354B38 2008

791.45′72—dc22

2007038435

Giving Thanks to the Lords of Kobol

Although the chapters in this book focus exclusively on the reimagined Battlestar Galactica, gratitude must be given first and foremost to the original series creator, Glen Larson. It’s well known that Larson didn’t envision Battlestar as simply a shoot’em up western in space—“The Lost Warrior” and “The Magnificent Warriors” aside —but added thoughtful dimension to the story based on his Mormon religious beliefs. Ron Moore and David Eick have continued this trend of philosophically and theologically enriched storytelling, and I’m most grateful to them for having breathed new life into the Battlestar saga.

This book owes its existence most of all to my friend Bill Irwin, whose wit and sharp editorial eye gave each chapter a fine polish, and to the support of Jeff Dean, Jamie Harlan, and Lindsay Pullen at Blackwell. I’d also like to thank each contributor for moving at FTL speeds to produce excellent work. In particular, I wish to express my most heartfelt gratitude to my wife, Jennifer Vines, with whom I very much enjoyed writing something together for the first time, and my sister-in-law, Jessica Vines, who provided valuable feedback on many chapters. Their only regret is that we didn’t have a chapter devoted exclusively to the aesthetic value of Samuel T. Anders.

Finally, I’d like to dedicate this book to the youngest members of my immediate and extended families who are indeed “the shape of things to come”: my daughter, August, my nephew, Ethan, and my great-nephew, Radley.

“There Are Those Who Believe...”

The year was 1978: still thrilled by Star Wars and hungry for more action-packed sci-fi, millions of viewers like me thought Battlestar Galactica was IT! Of course, the excitement surrounding the series premiere soon began to wear off as we saw the same Cylon ship blow up over and over... and over again, and familiar film plots were retread as the writers scrambled to keep up with the network’s demanding airdate schedule. At five years old, how was I supposed to know that “Fire in Space” was basically a retelling of The ToweringInferno?

Enough bashing of a classic 1970s TV show (yes, 1970s—Galactica 1980 doesn’t count). Battlestar had a great initial concept and overall dramatic story: Humanity, nearly wiped out by bad ass robots in need of Visine, searching for their long lost brothers and sisters who just happen to be... us. So it was no surprise that Battlestar was eventually resurrected, and it was well worth the twenty-five year wait! While initial fan reaction centered on the sexy new Cylons and Starbuck’s controversial gender change, it was immediately apparent that this wasn’t just a whole new Battlestar, but a whole new breed of sci-fi storytelling. While sci-fi often provides an imaginative philosophical laboratory, the reimagined Battlestar has done so like no other. What other TV show gives viewers cybernetic life forms who both aspire to be more human (like Data on Star Trek: The Next Generation) and also despise humanity and seek to eradicate it as a “pestilence”? Or heroic figures who not only acknowledge their own personal failings but condemn their entire species as a “flawed creation”? Or a character whose overpowering ego and sometimes split personality may yet lead to the salvation of two warring cultures? The reimagined Battlestar Galactica is IT!

Like the “ragtag fleet” of Colonial survivors on their quest for Earth, philosophy’s quest is often based on “evidence of things not seen.” The questions philosophy poses don’t have answers that’ll pop up on Dradis, nor would they be observable through Dr. Baltar’s microscope. Like Battlestar, philosophy wonders whether what we perceive is just a projection of our own minds, as on a Cylon baseship. Maybe we’re each playing a role in an eternally repeating cosmic drama and there’s a divine entity—or entities—watching, or even determining what events unfold. These aren’t easy issues to confront, but exploring them can be as exciting as being shot out of Galactica in a Viper (almost).

Whether you prefer your Starbuck male with blow-dried hair, or female with a bad attitude, you’re bound to discover a new angle on the rich Battlestar Galactica saga as you peruse the pages that follow. Some chapters illuminate a particular philosopher’s views on the situation in which the Colonials and Cylons find themselves: Would Machiavelli have rigged a democratic election to keep Baltar from winning? Other chapters address the unique questions raised by the Cylons: Would it be cheating for Helo to frak Boomer since she and Athena share physical and psychological attributes? Tackling some of the moral quandaries when Adama, Roslin, or others have to “roll a hard six” and hope for the best, other chapters ask questions such as: How would you have handled living on New Caprica under Cylon occupation? Then there are the ever-present theological issues that ideologically separate humans and Cylons: Is it rational to believe in one or more divine beings when there is no Ship of Lights to prove it to you? We’ll also take a look at other perspectives in the philosophical universe, which is just as vast as the physical universe Galactica must traverse: Does “the story that’s told again and again and again throughout eternity” most closely resemble Greek mythology, JudeoChristian theology, or Zen Buddhism?

So climb in your rack, close the curtain, put your boots outside the hatch so nobody disturbs you, and get ready to finally figure out if you’re a human or a Cylon, or at least which you’d most like to be.

So say we all.

PART I

OPENING THE ANCIENT SCROLLS: CLASSIC PHILOSOPHERS AS COLONIAL PROPHETS

1

How To Be Happy After the End of the World

Erik D. Baldwin

Battlestar Galactica depicts the “end of the world,” the destruction of the Twelve Colonies by the Cylons. Not surprisingly, many of the characters have difficulty coping. Lee Adama, for example, struggles with alienation, depression, and despair. During the battle to destroy the “resurrection ship,” Lee collides with another ship while flying the Blackbird stealth fighter. His flight suit rips and he thinks he’s going to die floating in space. After his rescue, Starbuck tells him, “Let’s just be glad that we both came back alive, all right?” But Lee responds, “That’s just it, Kara. I didn’t want to make it back alive” (“Resurrection Ship, Part 2”). Gaius Baltar deals with his pain and guilt by seeking pleasure; he’ll frak just about any willing and attractive female, whether human or Cylon. Starbuck has a host of problems, ranging from insubordination to infidelity, and is, in her own words, a “screw up.” Saul Tigh strives to fulfill his duties as XO in spite of his alcoholism, but his career is marked by significant failures and bad calls. Then there’s Romo Lampkin, who agrees to be Baltar’s attorney for the glory of defending the most hated man in the fleet. His successful defense, though, relies on manipulation, deception, and trickery.

Fans of BSG are sometimes frustrated with the characters’ actions and decisions. But would any of us do better if we were in their places? We’d like to think so, but would we really? The temptation to indulge in sex, drugs, alcohol, or the pursuit of fame and glory to cope with the unimaginable suffering that result from surviving the death of civilization would be strong indeed. The old Earth proverb, “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die,” seems to express the only kind of happiness that’s available to the “ragtag fleet.” Nevertheless, we do think that many of the characters in BSG would be happier if they made better choices and had a clearer idea about what happiness really is.

The Good Life: Booze, Pills, Hot and Cold Running Interns?

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), in his (), attempts to discover the highest good for humans, which he defines as . This Greek term roughly means living well or living a flourishing human life, what we may call “happiness.” Aristotle claims, “Every craft and every line of inquiry, and likewise every action and decision, seems to seek some good; that is why some people were right to describe the good as that which everyone seeks” ( 1094a1). But people often disagree about the nature of the highest good: “many think [the highest good] is something obvious and evident—for instance, pleasure, wealth, or honor. Some take it to be one thing, others another. Indeed, the same person often changes his mind; for when he has fallen ill, he thinks happiness is health, and when he has fallen into poverty, he thinks it is wealth” ( 1095a22–5). Despite such disagreement, Aristotle thinks we have at least rough idea of what happiness is supposed to be. Starting from “what most of us believe” Aristotle articulates a set of formal criteria that the highest good must satisfy: it must be complete, self-sufficient, and comprehensive.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!