Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

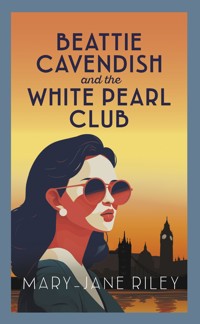

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

1948. The shadow of war still lingers over Britain and Beattie Cavendish, former Secret Operations Executive agent, refuses to settle into civilian life. When offered an undercover role at the newly formed GCHQ, the nerve centre of Britain's intelligence network, she doesn't hesitate. Her first mission is to infiltrate the powerful Bowen family and find out what she can about politician Ralph Bowen who is suspected of being a communist sympathiser. Her mission takes a deadly turn when the Bowen's housekeeper, Sofia, has her throat cut. As the investigation spirals, Beattie teams up with war-weary detective Patrick Corrigan to expose a dangerous web of spies and secrets all leading back to The White Pearl Club, a Soho establishment that caters to gentlemen with dangerous appetites. As powerful forces attempt to bury the truth, Beattie must survive a ruthless game of deception and the dark underbelly of 1940s Soho at the dawn of the Cold War.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

BEATTIE CAVENDISH AND THE WHITE PEARL CLUB

MARY-JANE RILEY4

5

To Seb and Raf

6

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

November 1948

The evening had begun well, with Ashley Bowen whisking her away in style in his Bristol convertible to the theatre in the West End. Ever since she’d homed in on him as instructed at Alicia Gainborne’s engagement party three weeks earlier, she’d been waiting for his call. Finally, it had come. She’d worked damned hard at that party to ensure he was attracted to her, fluttering her eyelashes and flattering him until she thought she might die of boredom. He was a thin man in a well-cut dinner jacket, with blond, wavy hair brushed back off his forehead. His nose was pointed and his chin weak, and she decided he was appropriately named as his looks and manner reminded her of Ashley Wilkes in Gone with the Wind. But she knew she would have made an impression because after all, she, Beattie Cavendish, was good at her job.

The Terence Rattigan play had been excellent, and Beattie left the Phoenix Theatre feeling moderately cheered, despite the cold and the drizzle that greeted them outside. She pulled the fur jacket her mother had given her closer around herself, while Ashley offered her his arm.

‘Bit dull, I thought,’ he said, as they walked down 8Charing Cross Road towards his car. ‘All that soul-searching at the end. Too much of that really isn’t good for you, don’t you think? Mind you,’ he laughed, ‘my classics teacher was exactly like that – stern and boring. No fun.’

Beattie smiled to humour him. ‘Really?’ she said. This job could become tedious.

‘Yes. Hated the subject at school. Preferred history and English.’

At last. Something in common. She tried again. ‘Me too. Have you read Graham Greene’s latest, The Heart of the Matter? It’s such a …’ She trailed off. Perhaps a novel about adultery and moral crises wasn’t quite the sort of light conversation she was striving for. ‘And then there’s Ernest Hemingway,’ she said instead. ‘I love his writing, don’t you?’ She sighed inwardly. She sounded so banal.

‘Er, yes?’ He looked uncomfortable, so Beattie cast around for other subjects to talk about.

He cleared his throat. ‘So, Cambridge?’

She nodded.

‘What did you read?’

‘Languages. As I told you, my mother is French and I seem to have an ear for languages. That’s why I …’ Beattie trailed off. Ashley looked more interested in the small round woman in an ancient coat singing ‘Danny Boy’ loudly but tunelessly to passers-by accompanied by a sorrowful man in a harlequin suit swaying mournfully to the woman’s song. Ashley put a couple of pennies in the dancing man’s proffered hat.

‘Bit unusual, isn’t it?’ he said, nodding at the singing woman. ‘For a girl to go to Cambridge?’

He had been listening. ‘A little.’ She would not tell him 9how important it was for her to be independent, to be able to earn her own money. That was the other Beattie, not the one who was supposed to hang on to Ashley’s every word.

‘Clever old you. It wasn’t for me, though.’

‘No?’ She knew this, but Beattie was glad to leave the subject of herself and get back to the subject Ashley was most interested in, namely himself.

‘No. Wanted to contribute to the war effort, so I joined up but didn’t see the fighting. The work I was doing was, you know, a bit hush-hush.’ He gave a little laugh.

‘Intriguing,’ said Beattie, knowing full well Ashley Bowen had been posted to a safe place and an ordinary desk job thanks to his family’s contacts.

‘I can’t really …’ Another self-deprecating laugh. ‘You know, talk about it.’

‘Of course you can’t.’ Beattie injected ounces of sincerity into her voice. ‘And now? Banking, I think you said?’

Ashley grimaced. ‘Yes. A bit of a bore, quite frankly, but a man’s got to do something to keep the wolf from the door in these times of austerity.’

‘Of course,’ agreed Beattie, also knowing he only worked two days a week at a bank owned by a friend of the family. ‘And we all thought everything would be as it was before the war, and instead three years later we still have rationing and even more deprivation than before.’ What was she doing? She needed to be light and positive and as if those things didn’t matter at all. ‘But never mind about all that. Tell me again about your summer holidays in Deauville before the war – my mother knows the town well.’ 10

As she tuned out Ashley’s voice, having heard about holidays in Deauville at the party where they met, she felt a kind of despair wash over her. Really, the conversation was as colourless as the London streets. She looked around and felt she couldn’t wait for the ‘dim-out’ that had been in place since the beginning of the war to end. There had been a little hope, a lifting of spirits when the Olympic Games had been held in London in the summer, but now she longed for neon lights and brash colours advertising Craven cigarettes, Bovril and Schweppes, and for people to be hurrying and bustling and enjoying life. The shadows of war still hung over them all, together with the scent of decay and despair.

Oh, but she was being too maudlin. Pull yourself together, Beattie Cavendish. You can do this. You’ve done worse.

She stumbled, slipping on the wet, uneven pavement, cracked from years of neglect. Ashley caught her elbow.

‘Pardon me, miss.’ A skinny man darted around her, tipping his hat before jumping aboard a passing bus.

‘Are you all right, Beattie?’ asked Ashley, solicitous, not letting go of her.

‘I’m fine, thank you. No harm done.’ She smiled as she smoothed down her jacket with one hand, the fur comforting on her skin. Her feet were hurting in the new shoes she had bought for the occasion, a blister on each of her heels.

There was a shout from behind. ‘Ash. Ash.’

She and Ashley turned and there was a young woman, waving. She had a sharp pixie haircut and was wearing an old greatcoat that swamped her figure. There was a 11glimpse of daffodil-yellow underneath the coat. With her was a tall man with a neat moustache and goatee beard. He was dressed in a suit and open coat, made less formal by the jaunty addition of a scarlet scarf around his neck. He was at least ten or fifteen years older than the young woman.

‘Felicia,’ said Ashley warmly, kissing the woman on her cheek.

Beattie noticed Felicia giving her a sharp look up and down.

Felicia. Ashley Bowen’s sister. Twenty-five. Lives in a flat in Soho. Single, no job. Dabbles in art. Beattie remembered the words in the manila folder presented to her when she was first given the job of getting closer to the Bowen family.

Ashley turned and shook the hand of the man with the goatee beard. ‘Gerald. How the devil are you?’

Gerald Silver, forty, sometime artist and playboy with a fondness for cocaine. Fought in North Africa. Single. Parents own a crumbling pile in the Cotswolds of which they can’t afford the upkeep. The family are old friends of the Bowens. Gerald is possibly homosexual. She’d laughed when she’d read that line, written by men in suits and an observation that quite probably sprang from the fact Gerald was an artist.

‘And who have we here?’ Gerald eyed Beattie up and down. It took all of Beattie’s self-control not to roll her eyes. The man was so obvious. However, she smiled as demurely as she could and held out her hand. ‘Beattie Cavendish.’

Gerald bent and placed his lips on the top of her hand. 12‘Ah, the young lady Ashley has barely stopped talking about. Delighted to meet you, Beattie Cavendish.’

‘Gerald,’ said Ashley, his face colouring.

‘I think,’ said Gerald, straightening up, ‘this calls for a drink.’ He peered up at the sky. ‘And we can get out of this wretched rain. Your place, Ash? What do you say?’

‘I thought we were going dancing,’ said Felicia, pouting.

‘Come on, Fee,’ said Gerald. ‘Have a thought for this old man’s health.’ He put a hand theatrically over his heart.

Felicia sighed, tapping her foot. ‘All right, then.’

‘Beattie?’ asked Ashley. ‘Will you join us?’

‘We are your chaperones,’ said Gerald, giving a theatrical bow.

Beattie thought longingly of a cup of cocoa, her nightie and her bed. ‘Lovely,’ she said, painting a smile on her face. ‘That would be lovely.’

If she said so herself, she was doing a damned good job at getting to know the family and friends of Ralph Bowen, Conservative Member of Parliament and Shadow Foreign Secretary.

CHAPTER TWO

There was still a light rain in the air as the Bristol pulled up outside the Bowens’ house in Chelsea. Justice Walk was a narrow road, a stone’s throw from the river and lined with houses that whispered of understated elegance.

The night was dark, lit only by the weak light of the street lamps. As Beattie clambered out of the car she could smell the comforting smoke of coal fires and was aware of the occasional whiff of the Thames – a musty, dank smell of seaweed and decay – and she heard the distant hooting of the tugboats. She stood for a moment, never ceasing to appreciate the sound of peace, the silence of peace. The absence of noise from sirens, from fighter planes, from frenzied shouting. The absence of the glow of fires in the distance as more poor souls died or were made homeless. The absence of that twist of fear as she went where danger lurked. She welcomed the dark.

She looked up at the house, which was a three-storey eighteenth-century building with elaborate pargeting over the front door and a stone lion either side. Ashley Bowen had rooms on the third floor – he had, she knew, been bombed out of his own home but had not yet returned. 14Beattie wondered if Ashley’s father, Ralph Bowen, with all his money and privilege and standing, was really able to empathise with those who had come back broken from the war, those who had lost everything, families who scavenged amongst the remains of ruined buildings. No wonder people had voted for Attlee.

The rain came down harder. Ashley opened the door and they piled into the hallway, keen to get out of the wet.

It was beautiful inside, as Beattie had known it would be. The cream tiled floor gleamed and a staircase down the hall and to the left curved gracefully up to the floors above. A gate-legged table stood to one side, a silver salver sitting on its polished top. For letters, perhaps? Beattie imagined a butler handling the silver salver with white gloves, transporting important letters written by Ralph and his wife, Edwina, on thick, creamy notepaper.

‘I do hope your father has a decent brandy, Ash,’ said Gerald, droplets flying everywhere as he shook his head and brushed the rain off the shoulders of his coat.

Ashley grinned. ‘I’m sure I can find you something to suit.’ He led them into the drawing room, where a fire burnt brightly, and two lamps on polished tables cast long, low shadows on the walls. Beattie noted the fresh flowers and silver photograph frames on the oval table, a baby grand piano with its lid raised, and, hanging over the mantelpiece, the portrait of a young woman. Edwina Bowen, perhaps? A television set squatted on another table in a corner. There were richly coloured Persian rugs on the floor.

‘Sit, sit.’ Ashley waved to two heavily stuffed sofas covered in yards of red silk opposite each other near the 15fire, a table in between. ‘Get warm, get dry.’ He walked over to the drinks cabinet and busied himself with retrieving glasses and bottles and decanters. ‘Martinis for you girls? And as it happens, I do have a decent brandy, Gerald.’

‘Excellent, never doubted it,’ said Gerald, relaxing back into one of the sofas, Felicia snuggled beside him. Beattie sat opposite, resisting the urge to perch on the edge in case she needed to make a quick exit.

Ashley put a tray of drinks on the table before dropping onto the seat next to Beattie. He handed her a Martini.

Beattie took a sip. It was delicious. Salty from the olive, sharp and dry from the alcohol.

‘A fine drop,’ said Gerald, holding his brandy up to the light.

Felicia sipped her drink. ‘I do hope Mummy and Daddy realise you use their rooms and drink their alcohol when they’re out, Ashley.’ Her barbed comment found its target as Ashley flushed.

‘They are happy for me to do so, yes.’

‘Hmm.’ Felicia put her drink on the table. ‘And when exactly are you moving back to your own house?’

Ashley frowned. ‘As soon as it’s ready. You know how it is, it’s difficult to obtain building supplies and so forth.’

‘And it’s far more comfortable here, eh, Ashley?’ Gerald grinned as he drank his brandy. ‘A cook, a housekeeper. So many people don’t have staff any more since they all buggered off to the munitions factories when war broke out. Don’t want to go back into servitude. But not here. Not at the Bowens’. Your father must pay them well. Marvellous, I do envy you.’ 16

Ashley snorted. ‘It’s not as if your flat is exactly one of the new pre-fabs.’

‘No, but sometimes the artist’s life does pall.’ He waved his hand. ‘You Bowens wouldn’t know anything about discomfort, though.’

‘But your studio is so romantic, Gerald,’ said Felicia, smiling with wide eyes. ‘I adore the smell of oils and white spirit and creativity.’ She had shed her greatcoat and was wearing a skirt – the daffodil colour Beattie had spotted earlier – together with a man’s jumper, judging by its cut and the way it dwarfed her slight figure. The ends of the sleeves were frayed.

‘Really, Felicia,’ said Ashley. ‘When have you ever been there?’ It was clear from the look on his face that he didn’t approve.

‘Gerald has asked me to sit for him once or twice. And I can learn from him. Not that it’s any business of yours, dear brother.’

‘Now, look here—’

‘It’s all right old chap,’ interrupted Gerald smoothly. ‘As you know, your sister’s quite safe with me.’ He picked up Felicia’s tiny hand in his large one and kissed her palm. Felicia giggled.

Beattie watched the exchange with interest, trying to work out the dynamics between the three of them. They had been friends for some time, though it was difficult to see where Gerald, being several years older than either Ashley or Felicia, fitted in. But there was an easy joshing between them that she would have expected, though also an undercurrent of something else too, something she couldn’t fathom. 17

Early days.

‘Remind me where you two met?’ asked Gerald.

‘Alicia Gainborne’s engagement party,’ said Beattie, slipping back into character, smiling and flashing a coquettish look at Ashley.

‘I see.’ Gerald picked up the decanter Ashley had thoughtfully left in front of him and poured himself and his friend a drink.

Beattie sipped her Martini. She stood up and walked over to the table of photographs. ‘Quite the rogues’ gallery you have here,’ she said, nodding to the array of portraits.

‘That,’ said Ashley, joining her, gulping at his drink and pointing to one of a group of stiff and serious men and women in Victorian clothes and flamboyant hats sitting on a rug in a woodland glade, ‘is my grandmother and her extended family on their annual picnic.’ He grinned. ‘They don’t look as though they’re enjoying themselves very much, do they? And here’ – he waved at a sepia photograph in a second frame – ‘is me and Felicia.’ Beattie saw two chubby children sitting self-consciously on an ottoman. Ashley, the taller of the two, was in short trousers and long socks; Felicia was wearing an unflattering haircut and a fussy dress. There was not a smile between them.

‘So serious,’ said Beattie.

‘I can remember being made to sit on that damn bit of furniture for what seemed like hours on end.’ He shuddered.

‘And your father with Winston Churchill.’ She admired another photograph in a silver frame.

‘Oh yes. The obligatory one with the great leader. My father’s very fond of that one.’ 18

‘You don’t approve?’

‘Of my father’s politics or Churchill? I neither approve nor disapprove, I’m afraid. It’s all too dull. Of course, it’s Father’s lifeblood.’

‘Has he always been a Conservative?’

‘Is the Pope Catholic?’ a voice drawled.

Beattie had almost forgotten about Gerald, who had obviously been listening to their conversation. He sat, a faint smile on his lips, one ankle resting on the thigh of his other leg, languid and louche. Yes, louche. That was the word for him.

Ashley grinned. ‘Gerald’s right. I think even the thought of being of any other political persuasion would give him the heebie-jeebies. What an odd question, what made you ask?’

Time to change the subject. She went over to the baby grand and stroked its polished wood. ‘And this is a beautiful piano. Does anyone play?’

‘The Steinway? My mother does.’ He took a silver cigarette case out of his pocket and offered it to Beattie.

She took a cigarette and leant forward as he steadied her hand and lit it. She inhaled a deep breath of smoke into her lungs, closing her eyes with pleasure. The taste and the smell took her back to another time, another place, another man. A time and place full of danger and love. She could almost smell the woodsmoke, hear the rat-a-tat-tat of distant gunfire, feel the hunger in her stomach. When she opened her eyes she found Ashley watching her quizzically.

‘I don’t think I’ve ever known a woman to smoke Gauloises,’ he said, as the pungent aroma wafted between them. 19

She blinked, dismissing the memories. ‘A bad habit I picked up in France. During the war.’ She smiled briefly. That much was true. She also knew he smoked Gauloises and saw it as an opportunity for them to have something in common.

‘And what is it you did during the war?’ said Felicia, her voice as sharp as her blood-red nails.

‘Nothing too exciting,’ Beattie answered lightly, looking down at her. ‘A bit of driving here and there. Ambulances, generals, that sort of thing. And now’ – she stubbed her cigarette out in the ashtray – ‘I must go and powder my nose.’

‘And what do you do now?’ There was nothing friendly about Felicia’s smile.

‘I teach young girls to type and to be generally adept around the office. For the Civil Service.’ It was her standard reply to questions about how she earnt her living – well, she could hardly tell people she translated signal intelligence from Russia and various other allies and did a bit of spying on the side, could she? Though it was a particularly dull cover story, and she felt duller every time she told it.

Felicia’s raised eyebrow was eloquence itself.

‘I’ll refill our glasses,’ said Ashley, cutting through the silence. ‘Up the staircase and second on the left.’

Beattie shut the drawing-room door behind her and stood for a moment. This was where she would like to go snooping, use her talents, the talents for which she’d been recruited, but she had to concentrate on the matter in hand. Get to know Ashley Bowen, and his family.

‘You have the connections,’ Anthony Cooper had told her, his gaze severe. ‘You were at Cambridge with his 20friend Julian Knight. That is your way in. Go to the party. But don’t do anything rash.’ Leave the important jobs to the men, had been the subtext of that particular remark.

No meddling.

She walked down the hallway, passing a door that was ajar. Something – she couldn’t say what – made her hesitate.

The room inside was dark, though there was the occasional sliver of light from the street lamps outside, and there was a definite breeze blowing, making the skin on her arms come up in goosebumps. Odd. She peered in as the curtains parted with the breeze and she thought she could see jagged edges of glass. A broken windowpane?

She stepped inside, her hand finding the light switch.

Nothing. No light. Strange.

She took her small torch out of her handbag and shone it around.

It was a study, that much she could tell. There was a bookcase along one wall, and dour pictures of landscapes hung on another. A grandfather clock ticked sonorously in the corner. There was a small grate with the remains of a fire. Two wing-backed chairs sat regally either side of the fireplace, and at the end of the room was a desk.

There was something in the air, as if it had been disturbed. A strange smell too, that overlaid the aroma of cigarette smoke and leather, one she recognised, but wouldn’t acknowledge what it might be. Not here. Not in Chelsea.

She made her way to where the breeze was coming from and yes, she had been right, the sash window had two broken panes, and it was partially open, but there was 21very little glass on the floor. Someone must have reached inside to push the latch before heaving up the window. She turned to the desk. There was a burgundy leather inlay with a sheet of well-used blotting paper, and a tortoiseshell and silver inkwell with matching stamp box. A letter opener lying by the inkwell looked as though it had been brought from India with its twisted ivory handle and sharp edge. She imagined Ralph Bowen opening important letters and signing documents at this desk. Perhaps there were stiff cards, stiff as a starched collar, with his name bossily imprinted upon them for him to make ready replies to invitations and enquiries.

Putting her handbag on the floor, she tried the top drawer. Locked. As were the other two. Damn. Should she use her picks?

Something made her stop and stand stock still. There it was again. The feeling that all was not well. A ripple in the atmosphere. And all at once a familiar smell. No, she had to be imagining things. She shook her head, directing the beam of her torch towards the side of the desk, to check, to be sure.

And there was a stockinged ankle, a sensible black shoe half on, half off a foot, and the smell was that of congealing blood.

Beattie went behind the desk and knelt down with some hope that she could help, that perhaps the woman had merely fallen and bumped her head.

The woman’s throat had been cut with savagery and efficiency. Blood pooled blackly around her neck and under her shoulders. Beattie breathed through her nose, trying to rid herself of the ferrous smell coating the inside of her 22mouth and throat. It had been a long time since she’d seen so much blood and she’d forgotten the iron stink of it, the viscosity of it. This had been a violent death.

The legs of the dead woman were splayed at an awkward angle, and her thick tweed skirt had ridden up over her knees. Beattie itched to pull it back down, but she knew she mustn’t. Strands of inky black hair had come loose from the woman’s bun and her dead eyes stared at Beattie. What had she seen in her final moments?

Such a lonely death.

She could do one thing for the woman. Gently, she closed those pleading eyes, gave her some peace.

Beattie sighed. It was time to get the family involved, whatever the consequences for her, but before she could act she heard a step, felt a movement of air, smelt a sharp, sour smell and an arm was wrapped around her neck and increasing pressure was applied to her throat. She struggled, trying to wrench herself free, to find his eyes with her fingers, but he was holding her too tightly, pinning her body against his.

Air. She couldn’t get air. She couldn’t breathe.

CHAPTER THREE

Patrick Corrigan was cold. Wet. Tired. He hunched his shoulders as if he could burrow down further into his seen-better-days coat. The rain dripped off the brim of his hat and the cold needled through the thin soles of his shoes and up his legs. A sulphurous yellow light from the street lamps was reflected in the growing puddles around him. Jazz music filtered out from seedy bars. His empty eye socket was throbbing, and his good eye twitched with fatigue.

Soho. A dirty maze of streets where there were places catering for every taste.

He cursed as a bus passed him, splashing him with filthy water. People hurried by, huddling under their umbrellas, keen to get home out of the wet and the cold. Lucky buggers. Working girls not dressed for the November weather loitered in doorways, smoking, occasionally calling out to passers-by. They called to him; he shook his head, smiling, not wanting a few minutes of dubious pleasure in a piss-scented alleyway. Still, standing on the opposite side of the road from a club with a very dodgy reputation waiting for a man to finish whatever he was 24doing at said club was not a great pleasure either, nor was it how he had imagined spending the rest of his life.

The club occupied a basement beneath the Dandelion Grill in Dean Street. It didn’t announce itself, and no one would know it was there were it not for the furtive looks given by the well-dressed men who made their way up and down the stairs. The women were more brazen, not giving a stuff if anyone was looking. Corrigan admired that.

‘Hello, handsome. Got a light?’

Corrigan patted his pockets. ‘Here,’ he said, sparking the lighter. A man leant into him. Corrigan registered a face with fine features, thin cheeks chalky with white powder, lips painted violet and eyes rimmed with black. His hair was neat and short, with a sharp parting, though plastered to his head by the rain. He touched Corrigan’s hand lightly with his fingers as he drew on his cigarette.

‘You going in?’ the man said, indicating the club across the road.

‘In?’ Bloody hell, so much for him not being noticed.

The man grinned. ‘The White Pearl. The club. I’ve been watching you and you seem … interested? If you’re not a member, I could vouch for you.’

‘Er, no. No thanks. I’m not …’ Corrigan felt his face flame and was thankful for the dark. ‘Interested. I’m waiting for someone.’

‘Of course you are. It’s just you seemed a bit lost?’

‘No. I’m not—’

‘Not lost?’ The man smiled.

Corrigan shook his head. ‘I’m not – lost. Thank you.’

‘Shame. Au revoir, dearie.’ The man walked away, darting across the road avoiding both cars and puddles. 25Corrigan watched as he went down the stairs, giving a wave of his fingers.

Corrigan grinned to himself and touched his eye patch. It was a long time since he had been called handsome. A long time since he’d been propositioned.

The rain fell harder.

How much longer was he going to have to wait?

And how much longer was he going to have to do this job? Tailing people – mostly men who were adulterers or those who wanted to provide the evidence for a divorce – had not been his number one priority when setting up his own detective agency. But what had he expected? That he would be solving mysteries, bringing the criminals, the gangsters to justice? At first he was trying to find missing people, soldiers who’d returned home to less than a hero’s welcome, who’d turned to drink or to drugs to help them cope, but had then simply fled their lives, leaving their families wondering what had happened to them. But after a while he wasn’t asked to look for the desperate, but for the man who’d run off with the family money, or the man who’d run off with someone else’s wife. Tawdry. And if anyone needed a seedy hotel in which to stay, he could point out a fair few. But then nor had he been happy with the idea of going back to Ireland and helping out his brothers on the farm. As if he had never been away. He didn’t want that. Nor did he want the steady job on offer from Nell’s father. The sacrifices of the long years of war before had to be for something.

Nell wanted him to have a steady job. She wanted regular money and a family. Perhaps a move to the country. Sunday lunch with her parents every week. The pictures 26occasionally. Corrigan had thought he wanted that too. After all, Nell had waited for him for the last two years. And he tried to be at least some of what she wanted him to be, God he tried. But he didn’t know how much longer he could keep it up. What an utter bastard he was.

There. Coming up the stairs, looking up at the sky before unfurling his umbrella, was Ralph Bowen.

As Bowen crossed the road and came towards him, Corrigan moved back into the shadow of a doorway, grinding his cigarette under his shoe.

His quarry strode by, looking neither right nor left.

Corrigan let him get some fifty yards ahead before he began to follow.

Rain was dripping down his neck and his shoes and socks were soaked through as he trudged behind Bowen down the ill-lit streets still teeming with people. Bowen gave no sign he knew he was being followed. No crossing and re-crossing the road, no sudden tying of a shoelace, no looking at reflections in windows. And why should he? He wouldn’t suspect that his wife to whom he’d been married for thirty years would even contemplate hiring a private detective to follow him. Particularly an Irishman who operated from a grubby little office in Clapham. Particularly as he was a respectable Conservative politician and one who was destined to be in a very powerful position if the Tories were elected once more. He would not suspect his wife believed he was up to no good. The question Corrigan kept asking himself was: why had Edwina Bowen not already confronted her husband when Corrigan had given her his reports of him visiting that particular sort of club in the back streets of Soho? Why did she want him to 27continue with the job of seeing what her husband was up to? If he were a lesser man he wouldn’t be asking himself these questions, he would accept the money without too much thought, but he prided himself on his integrity, so he did ask them.

Bowen stopped and looked at his watch. Corrigan stopped also, melting again into a doorway. Bowen did not turn around. He carried on walking.

What was Bowen going to tell his wife tonight about where he had been? To his gentlemen’s club was, Corrigan imagined, his excuse of choice. Did not all politicians and men of his class have those sort of clubs? Secret societies. And unless his wife wanted to break into that bastion of masculine solidarity, she could not contradict him. Also, his high-powered friends would protect him whatever sort of person he was.

The rain was falling fast and hard now. It was getting late and they’d been walking for nearly an hour, down Piccadilly, along to Sloane Square and into the very posh part of London. Corrigan thought almost longingly of his office with its smoky fire and second-hand furniture. It wasn’t much, but it was private and somewhere he could pour himself a drop of Irish whiskey. He was almost certain Bowen was heading for home; indeed, he fervently hoped so as he didn’t relish standing out in the cold and wet while Bowen entertained himself and another in a warm and fuggy room, but he needed to follow him to the bitter end to make sure.

The whole of Corrigan’s left side began to ache, including his empty eye socket. It was the rain and cold really getting to him, creeping inside his body, wrapping 28itself around his bones. Bowen walked on, passing a bombsite with weeds growing through the rubble. Another ruddy hole in the cityscape. Even the well-to-do hadn’t escaped the Blitz. Corrigan thought he could see the signs of a small fire behind one of the broken walls, doubtless some poor sod without a roof over his head. God, but it was miserable.

They tramped on.

Corrigan was shivering hard and gave a small sigh of relief as he saw his target stop at the corner of Glebe Place and climb steps into a church that had done well to escape the bombing. Interesting. This was the third time in the last month Bowen had visited St Margaret of Antioch and the third time Corrigan had followed him in. If he wasn’t careful, the parish priest would begin to think he was a regular.

Corrigan slipped quietly through the door, pushing his eyepatch into his pocket. People didn’t tend to notice his empty socket, not at first anyway. But the patch that made him look like an adventurer was certainly memorable. He pulled his hat further down his forehead and, out of habit, dipped his fingers into the holy water and crossed himself.

The church smelt of damp and candlewax and incense. So familiar. Comforting, even. The ceiling soared away to the heavens, murals of angels and saints gazing benevolently down upon him. A statue of the Madonna with a despairing face and beseeching arms loomed to one side of the altar, surrounded by flickering candles. St Joseph, who looked bloody cross, was on the other, also surrounded by celestial light.

There were four other people in the church – two men 29in greatcoats that had seen better days and which he could smell even at a distance, a woman wearing a black veil saying her rosary, the black beads threaded through her fingers, and a third man on his own, kneeling before a statue of what Corrigan presumed, from the fact it was a woman but not the Madonna, was St Margaret of Antioch. He would take a guess the two men had come into the church to get warm and the third had a pressing problem he needed to pray about. Good luck to them.

Bowen had taken a seat near the altar rail. Corrigan thought of his long-dead father, who always sat at the back of the church during Mass, thoroughly disapproving of those who marched to the front. ‘God likes a humble man,’ was his mantra. Thus Corrigan slid into a pew at the back, keeping his head bowed low. He knelt, wincing as his bad knee made contact with the bare wood of the kneeler, and joined his hands as if in prayer.

He glanced up as a tall priest with an angular, ascetic face, his hands tucked into his cassock, came out of the sacristy and crossed over to Bowen. Corrigan watched as the priest sat beside the politician and began to talk earnestly. They were too far away for Corrigan to hear anything but the murmur of their voices. Was the priest only talking to Bowen about God and prayer and sin, or was there something more to it? Had Bowen had a Road to Damascus epiphany? Somehow Corrigan doubted it.

The priest laid a hand on Bowen’s shoulder, then stood and made his way to one of the men in coats, who shook his hand. He moved to the next.

Bowen shuffled out of the pew and made his way up the aisle, looking neither left nor right. That was interesting. 30Ralph Bowen in a Catholic church when he was not a Catholic, although Edwina Bowen was. Bowen had not converted on their marriage. That could have been difficult for Edwina Bowen. No papal blessing for them. Perhaps Bowen was finally repenting his sins. Corrigan doubted that very much. As far as he knew, Bowen had kept his head down during the Great War and the next. Asthma had been his excuse for securing a desk job in the War Office during the last lot. Lucky sod. Left it to the cannon fodder to fight for peace and freedom and all that bollocks.

Corrigan kept his head bowed and his hands together as Bowen went past him, leaving the church through the carved wooden door.

As Corrigan followed, he knew they were on the way back to Bowen’s grand house, and for that Corrigan was grateful. Bowen walked with an almost jaunty air, as if a burden had been lifted off his shoulders. God must have got to him. Forgiven him his sins.

Bowen ran up the steps, opened his front door and disappeared inside. Corrigan noticed he closed it behind him very quietly.

Corrigan turned away. He was not required to stand outside the house all night, thank God. He’d done his job for the day. Time for that whiskey and whatever leftovers he could find in his cupboard, if he could be bothered. He stopped to light a cigarette and take the smoke deep into his lungs. Better.

A noise came from the Bowens’ house. It sounded like a strangled scream that was cut off abruptly.

Corrigan didn’t hesitate. Throwing his cigarette down onto the ground, he ran as fast as his bad leg would allow 31through the Bowens’ gate and into the garden, crunching something underfoot. Glass. He looked around. There. A couple of panes in a downstairs window had been broken, and the curtain was half drawn. He peered in and made out two struggling figures. One, who appeared to be wearing some sort of mask, had an arm locked around a woman’s neck. In the dim light there was the glint of a knife.

‘Oi!’ He shouted. ‘What are you doing?’ A rather silly question in the circumstances, he would think later, but one that was appropriate at that time. The person in the mask – and he couldn’t make out whether it was a man or a woman – was moving the knife closer and closer to the woman’s neck. Her eyes were wide and she was desperately grappling at an arm.

Bugger. Where was his gun when he needed it? At the office in the drawer, of course.

He saw the sash window had been pushed up a little, so he put his hands on the frame and opened it enough for him to be able to fling himself through and into the room, launching himself at the woman’s attacker. At the same time, the woman stamped down hard on the attacker’s foot, causing them to howl in pain. Sharp heels, he noticed, somewhat inappropriately. The woman then elbowed the attacker in the face before pulling herself free, causing the masked attacker to throw down the knife, sticky with blood, and jump through the open window. Corrigan tried to grab the attacker’s coat as they passed, but failed, landing on the floor with a thud.

‘And who the dickens are you?’

The woman he had rescued looked down at him, panting. He saw a strong nose, a red lipsticked mouth and 32raven hair in what Nell would probably call ‘soft waves’. And piercing blue eyes that looked extremely angry under well-defined eyebrows. There were diamonds in her ears and at her throat, and her green dress had a tear at knee-height. Odd what details he noticed. Not a beauty, but what? Intriguing, that was it.

‘Er …’ Her anger surprised him; he had expected a little bit of gratitude at the very least.

‘I almost had him.’ Her voice was husky, probably due to damage to her throat.

‘Him?’

She nodded. ‘Him. Yes. He was strong, but I was quite capable of dealing with him on my own. Then you came along.’ It hurt her to talk, he could see that. Posh voice, though.

‘I was only trying to help.’

‘Well you didn’t.’

Corrigan raised his eyebrows.

She saw. ‘What? You expect me to be grateful? Did you think of yourself as a knight in shining armour rescuing a damsel in distress?’

Corrigan put up his hands as if to ward her off. ‘No. I …’ He stopped as he saw a foot. And a body hidden by the mahogany desk. There was a scarf of black-red blood around her neck and more blood pooled about her head. ‘Who’s that?’

The woman’s shoulders slumped. ‘I don’t know who she is, but I’d better go and phone the police and then tell the family there’s a body in the library.’

‘Like Agatha Christie,’ he murmured.

‘I beg your pardon?’ 33

He shook his head. ‘Ignore me. I was being facetious.’ He crawled over to the body, trying to look at the woman dispassionately. Young. Slavic, he thought. Poking out from under an outstretched hand was the corner of a book of matches. He palmed the book, slipping it into his pocket, then pulled himself up, trying not to wince as his bad leg almost gave way. ‘This looks like a cold-blooded execution,’ he said, frowning. He looked up as he heard a noise. A car, he thought, going fast. ‘Did you hear that?’

‘What?’

‘A car.’

The woman listened. ‘No.’

‘No,’ said Corrigan, unaccountably disappointed. ‘It’s gone now anyway. And I’d better disappear.’ There was no need to hang around; this rather strange woman was able to cope quite admirably with the situation.

‘Really? Why?’

He gave a lopsided smile. ‘To let you tell the family about all this. It’s a wonder they didn’t hear anything.’

‘Far too absorbed in themselves.’

‘I see. But Mr Bowen might have …’ He stopped, realising he was about to reveal too much.

Too late. Her eyes narrowed. ‘Might have what? And what do you know about Ralph Bowen?’

‘He’s a … friend.’

‘A friend. Really.’ Her voice dripped with disbelief. ‘Yet you climbed through the window rather than ring the bell like any normal “friend”?’

He shrugged, went over to the window and climbed out, catching the palm of his hand on a shard of glass on the sill. Blood bloomed on his skin. Damn. He sucked at 34the wound. ‘I heard you scream, so came in the quickest way. Do me a favour. Don’t tell anyone you’ve seen me.’

She looked at him quizzically.

‘Might muddy the waters.’ He smiled. Something told him he could trust this woman. ‘But you’re right. I’m not a friend. I’m a private detective. I don’t like policemen much. Oh, and don’t touch the knife.’

He disappeared from sight.

CHAPTER FOUR

Beattie emerged from Green Park Tube station and began the short walk to her place of work in Mayfair. The sky was clearing and there was a tiny patch of blue – not enough to patch a sailor’s trousers, but still enough to lift the heart, and Beattie thought back to how she came to be here, walking along Piccadilly, then to Half Moon Street and on to Chesterfield Street.

‘We are in the middle of a spider’s web, my dear Miss Cavendish,’ the man with the bald head that was like a polished egg and who went by the name of Walter Smith had told her at the meeting in the Eagle public house. It was the Lent term of Beattie’s final year at Cambridge. His eyes, like insects through the pebble glass of his thick-rimmed spectacles, were watchful.

‘GCHQ – as we are soon to be known as – and in particular the Covert Operations Section, spreads that web far and wide. We play an important role in the security of the country; do you understand, Miss Cavendish?’ This from a man who’d introduced himself as Anthony Cooper, a man with extraordinarily pale eyes that, combined with very pale skin, made him seem like a 36ghost. Which of course he was in many ways.

Beattie had nodded, a flutter of excitement in her stomach. The three years at Cambridge directly after the war had managed to excise some demons, but all the partying, the heady excesses and the restlessness that accompanied those excesses had left her wanting something different. Something solid but not dull. A job that offered her the security of being able to make her own decisions. She was determined not to give in to her mother’s wishes for her to attend some ghastly finishing school with a view to finding a suitable husband. Oh, she knew that women were being pushed out of jobs when men came home from Europe and the Far East so it would prove difficult to find employment after her three years at Cambridge, but she had hoped to secure some sort of translation work, maybe. How her mother had sniffed at that idea. For Beattie, work meant money, which meant power over her own future.

And so when, whilst sipping sherry in the fusty-smelling rooms of her professor at the university, he had suggested there were a couple of people for her to meet, and maybe she would care to go to the Eagle at an appointed time in the next week or so? She had, as had been intended, been intrigued, and readily agreed.

‘And the Covert Operations Section …?’

‘We like to call it COS,’ Anthony Cooper had said. ‘You will find we like our acronyms.’ His thin lips had given a thin smile. ‘And if you were going to ask how secret COS is, then it’s very secret.’ After sipping delicately and disdainfully at his pint, he went on to talk about patriotism and serving her country. How her experiences during the war and her proficiency in languages could be most useful. 37‘You would need a little training, Miss Cavendish, but your experiences with the French Resistance mean that you have plenty of experience in the field.’

Beattie had sat in her chair, rattled, though she’d kept her expression interested, thoughtful. How did they know about France? But then, if COS was part of this GCHQ organisation, they would know. But how much did they know?

‘You will of course be unable to tell anyone, anyone at all about your work and you have already signed the Official Secrets Act.’

Beattie nodded and that had been that.

She hadn’t seen the man with the watchful eyes, Walter Smith, since, although she did have a very strange phone call from him as she was undergoing her training at Mannington Hall in Norfolk. ‘I want to give you a telephone number, Miss Cavendish, in case you should ever need to speak to me and me alone,’ he had said to her.

‘Oh?’ Beattie had been confused.

‘Don’t think about it, don’t worry about it. Merely take a note of it and use in extremis. Tell no one.’

He then dictated a number to her, which she tucked away and, as Walter Smith had advised, thought no more about.

When she turned up for her first day at work she was given a folder full of papers to translate, very dull papers, she was to find, and this carried on for some weeks until Anthony Cooper had called her into his office to inform her of ‘a little job’ he wanted done. That was when her heart had leapt with excitement as she was told to become close to the Bowen family. And she was doing as she had 38been asked, from the first time she had ‘bumped’ into Ashley Bowen at that rather ghastly party and engaged his interest, being ‘surprised’ to find they had friends in common – all part of the reason she had been chosen for the job.

She reached her building, which would have been grand in its day, its black railings topped with silver arrow finials – renewed after the originals were taken for the war effort – and a large, thick door, though when she first stepped inside she was brought down to earth. The vast hall was painted a utilitarian green and the grand chandelier that hung over the sweeping staircase could have done with a good clean. There was a desk to one side, at which sat Enid Laing, a formidable figure always immaculately dressed in a navy suit and carmine lipstick and who was both a secretary and receptionist, though she was affectionately known as ‘the gatekeeper’. The doors off the hallway didn’t lead to dining rooms or libraries, but to offices. No numbers or nameplates on the doors. Beattie’s office was the third door on the right and had probably been a dining room or similar in a previous life, with its proportions ill-suited to being a place of work. The ceiling was high, adorned with elaborate cornices, and the windows were tall and draughty. She hoped it would be warmer in the summer.

Hanging her coat and scarf on the coat stand in the corner, she went to her desk, saying hello to the five other people she shared the room with. They were men, who scarcely looked at her as she crossed the room, two of them mumbling a ‘good morning’ into their files. Rory Clarke, an earnest young man with pimples and halitosis, 39was the only one to look her in the eye and greet her with a firm nod. Beattie didn’t mind their lack of engagement; she knew there were many men around who simply thought that a woman should be searching for a husband, not working in a responsible job.

She looked at the piles of paper on her desk. Papers that had come from all over the country from operators in small rooms listening in to communications from allies and enemies alike. Papers in French and Polish and Russian for her to translate and send to the powers that be on one of the top floors, for them to decide which were important and which were not.

But the murder of the young woman at the Bowens’ house had been at the forefront of her mind for the last two days. Her name was Sofia Huber, a housekeeper for the family. Only twenty-five years old. Not for the first time she felt the swell of anger at the way it was being swept under the carpet. She looked at the article she had torn out of the newspaper, knowing its contents by heart. It outlined the ‘sudden death’ of a young woman at a politician’s house in Chelsea. Scotland Yard was investigating. That was about it. Her throat burnt with the injustice. Surely Sofia Huber was worth more than this? She deserved justice, and even a man as powerful as Ralph Bowen should not be allowed to behave as though such a crime was too unimportant for his attention. Even the police were in his pocket.

She had not enjoyed the interview with the police, a more probing one than she would have liked, as if they were trying to find something wrong with her story.

‘Why did you go into the study?’ the oleaginous Detective Inspector Dicky Morgan asked as she sat in a 40drab, windowless room with a table and two chairs either side of it. Morgan not only had an oily manner, but his slicked-back thinning hair gleamed with oil. His suit was sharp, as were his eyes. His fingers were nicotine-stained from the cigarette he held seemingly permanently between them. He had been called to the house in Chelsea straight away. Apart from him and the forensic photographer, no one had been allowed to examine the crime scene.

‘The door was ajar and there was a draught,’ she replied.

‘What did you find?’

‘I found a broken pane of glass in the window – two, actually – and a body. Sofia Huber’s body. Her throat had been cut.’

‘And then you were attacked?’

‘I was.’

‘Your attacker got away?’

She nodded. ‘He did.’ And it was at this point she should have mentioned the Irishman, but she did not. There was no need; he was irrelevant. And she did not like Detective Inspector Dicky Morgan. She knew he would do nothing about the killing, but maybe, just maybe, the Irishman might help. Best not to get him into any trouble, then.

‘What was your relationship with the deceased?’

‘I have never met her,’ said Beattie calmly.

‘What is your relationship with the Bowen family?’

‘I met Ashley Bowen at a party and he asked me to accompany him to the theatre.’

‘Why?’

That one stumped her for a minute. ‘Because he liked me, I would assume. That’s the normal reason for two 41people to enjoy an evening together. Perhaps it’s a question for him.’

‘Perhaps.’

On and on the questions went, round and round.

‘Where do you work, Miss Cavendish?’

‘I’m a civil servant. I teach girls to type.’

‘We will check.’

‘Please do,’ she replied, knowing the cover would hold if anyone went looking for any anomalies.

Eventually Detective Inspector Dicky Morgan became tired of all the questions himself and let her leave after she had signed her statement.

Odious little man.

She crumpled the newspaper article in her hand and dropped it into the wastepaper bin, then took an envelope out of her handbag. Inside was a letter that had arrived for Beattie that morning – an invitation from Edwina Bowen to join her for tea at four o’clock on Thursday. To thank you for your discretion, it said. Beattie would reply later.

The telephone on her desk rang.

It was Jennifer, Anthony Cooper’s secretary. ‘Mr Cooper would like to see you upstairs. Pronto.’

Beattie pushed away her unfinished work.

Anthony Cooper’s office was on the first floor and contained a desk, a small electric fire in a large fireplace and a green plant that could have done with watering. The room smelt of stale tobacco and burning dust. When Beattie entered, he was writing in a manila folder, his Waterman fountain pen scratching across the paper. He waved the pen at the hard chair in front of him. Beattie sat.

For a few minutes, the only sounds Beattie heard 42were that of the pen, a ticking clock and a car backfiring. Eventually Anthony Cooper looked up with a semblance of a smile. He laid his pen down.

‘Miss Cavendish. Your translation work is exemplary.’

‘Thank you, Mr Cooper.’

‘How is our little assignment progressing?’ He cocked his head to one side.

Beattie’s mouth was dry and she would have loved to have had a cup of tea, or even a glass of water from the jug on the desk, but neither were on offer.

‘As you know, Beattie, we had heard a certain amount of chatter about the Bowens, which is of course why you have been asked to become friendly with the family. But most particularly we want to know about Ralph Bowen. Anything you can tell us, anything at all, could prove extremely useful.’ He patted his pockets and took out his pipe. Then he rummaged in them for his pouch of tobacco. He proceeded to fill the bowl of his pipe before laying it on the table. ‘I’m sure his son could be a mine of information.’