6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

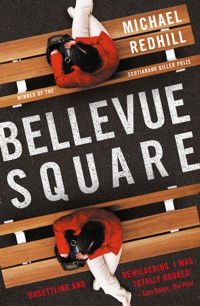

Winner of the 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jean Mason has a doppelganger. She's never seen her, but others* swear they have. *others | noun. A peculiar collection of drug addicts, scam artists, philanthropists, philosophers and vagrants - the regulars of Bellevue Square. Jean lives in downtown Toronto with her husband and two kids. The proud owner of a thriving bookstore, she doesn't rattle easily - not like she used to. But after two of her customers insist they've seen her double, Jean decides to investigate. Curiosity grows to obsession and soon Jean's concerns shift from the identity of the woman, to her very own. Funny, dark and surprising, Bellevue Square takes readers down the existentialist rabbit hole and asks the question: what happens when the sense you've made of things stops making sense?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

BELLEVUE SQUARE

Jean Mason has a doppelganger.

She’s never seen her, but others* swear they have.

*others | noun. A peculiar collection of drug addicts, scam artists, philanthropists, philosophers and vagrants – the regulars of Bellevue Square.

Jean lives in downtown Toronto with her husband and two kids. The proud owner of a thriving bookstore, she doesn’t rattle easily – not like she used to. But after two of her customers insist they’ve seen her double, Jean decides to investigate. Curiosity grows to obsession and soon Jean’s concerns shift from the identity of the woman, to her very own.

In this darkly comic novel, Redhill takes readers down the existentialist rabbit hole, exploring the surprising and disturbing plasticity of self, and what happens when the sense you’ve made of things stops making sense.

About the author

© Amanda Withers

Michael Redhill is the author of the novels Consolation, longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, and Martin Sloane, a finalist for the Giller Prize. He’s written a novel for young adults, four collections of poetry and two plays, including the internationally celebrated Goodness. He also writes a series of crime novels under the name Inger Ash Wolf. His most recent novel, Bellevue Square, won the 2017 Giller Prize. Michael lives in Toronto.

Winner of the 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize

#1 National Bestseller

A Globe and Mail Best Book of 2017

A National Post Best Book of 2017

A CBC Best Book of 2017

A Kobo Best Book of 2017

A NOW Magazine Best Book of 2017

‘To borrow a line from Michael Redhill’s beautiful Bellevue Square, “I do subtlety in other areas of my life.” So let’s look past the complex literary wonders of this book, the doppelgangers and bifurcated brains and alternate selves, the explorations of family, community, mental health and literary life. Let’s stay straightforward and tell you that beyond the mysterious elements, this novel is warm, and funny, and smart. Let’s celebrate that it is, simply, a pleasure to read’

– The 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize Jury

‘The opening chapters of this new opus, Bellevue Square, stick closely to the grip-lit script: simple, compelling prose, sudden plot twists, looming violence and a female narrator who swiftly proves unreliable. But as the reader becomes more and more absorbed in the story, the book quietly becomes something else. Something mystifying and haunting and entirely its own… reading Bellevue Square is as captivating as it is unsettling… This modern ghost story… will not soon be forgotten’

– Toronto Star

‘Longlisted for the Giller Prize, Bellevue Square is something of a performance… In its taut span of 262 pages, Bellevue Square features several narrative and tonal hairpin turns. With each of these, our admiration for Redhill’s storytelling dexterity burgeons… I’d rather be lost in Redhill’s ghost story than grounded in your average slab of tasteful literary realism’– The Globe and Mail

‘Described often as a dark, comic thriller, Bellevue Square is packed full of themes keeping the reader a little off balance but always entertained’ – Vancouver Sun

‘Not since Paul Auster’s City of Glass has there been a novel this engaging about doppelgangers and the psychological horror they wreak… As chilling as that stranger you’re pretty sure has been following you all afternoon’ – The Title

‘[A] moving and beautifully written memoir’ – CBC Books

‘There’s a boldness to [Bellevue Square] and, at its best, a genuine thrill’ – The Walrus

‘Sit yourself down in Bellevue Square and watch as parallel worlds collide. Redhill has written a mind-blowing brainteaser of a novel with plot twists worthy of David Lynch. A brilliant tribute to those among us whose brains are wired differently’ – Neil Smith, author of Boo

‘By turns harrowing and mesmerizing’ – Quill & Quire

‘Even as we start doubting Jean we can’t stop loving her. Along the way, Redhill gives us a ton of twists and turns and makes Toronto one of the stars of the show’ – NOW

For Elizabeth Marmur and Ruth Marshall

‘I and this mystery here we stand.’

walt whitman

‘Song of Myself’

1

my doppelganger problems began one afternoon in early April.

I was alone in the store, shelving books and humming along to Radio 2. Mr Ronan, one of my regulars, came in. I watched him from my perspective in Fiction as he chose an aisle and went down it.

I have a bookshop called Bookshop. I do subtlety in other areas of my life. I’ve been here for two years now, but it’s sped by. I have about twenty regulars, and I’m on a first-name basis with them, but Mr Ronan insists on calling me Mrs Mason. His credit card discloses only his first initial, G. I have a running joke: every time I see the initial I take a stab at what it stands for. I run his card and take one guess. We both think it’s funny, but he’s also shy and I think it embarrasses him, which is one of the reasons I do it. I’m trying to bring him out of himself.

He’s promised to tell me if I get it right one day. So far he hasn’t been Gordon or any of its short forms, soubriquets, or cognomens. Not Gary, Gabriel, Glenn, or Gene and neither Gerald nor Graham, my first two guesses, based on my feeling that he looked pretty Geraldish at times but also very Grahamish, too. He’s a late-middle-aged ex-academic or ex-accountant or someone who spent his life at a desk, who once might have been a real fireplug, like Mickey Rooney, but who, at sixty-plus years, looks like a hound in a sweater. There is no woman in his life, to judge by the fine blond and red hairs that creep up the sides of his ears.

I know he likes first editions and broadsides, as well as books about architecture and miniatures. I keep my eye out for him. And he’s a gazpacho enthusiast. You get all kinds. I always discover something new when Mr Ronan comes in. For instance, you can make soup from watermelons. I did not know that.

He came around a corner and stopped when he saw me. He was out of breath. ‘There you are,’ he said. ‘When did you get here?’

‘To the Fiction section?’

‘You’re dressed differently now,’ he said. ‘And your hair was shorter.’

‘My hair? What are you talking about?’

‘You were in the market. Fifteen minutes ago. I saw you.’

‘No. That wasn’t me. I wasn’t in any market.’

‘Huh,’ he said. He had a disagreeable expression on his face, a look halfway between fear and anger. He smiled with his teeth. ‘You were wearing grey slacks and a black top with little gold lines on it. I said hello. You said hello. Your hair was up to here!’ He chopped at the base of his skull. ‘So you have a twin, then.’

‘I have a sister, but she’s older than me and we look nothing alike.’ I don’t mention that Paula is certain that G. Ronan’s name is Gavin. ‘And I’ve been here all morning.’

‘Nuh-uh,’ he said. ‘No, I’m sure we…’ He left the aisle. My back tingled and I had the instinct to move to a more open area of the store, where I could watch him. I went behind my cash desk and started to pencil prices into a stack of green-covered Penguin crime. I flipped up their covers and wrote 5.99 in each one, keeping my eye on my strangely nervous customer. Finally, he came out of the racks with The Conquest of Gaul and put it down on my desk.

‘Oh… Mr Ronan? I wanted to tell you I found a pretty first edition of Miniature Rooms by Mrs Thorne. Original blue boards, flat, clean inside. Do you want to see it?’

‘Yes,’ he said, like it hurt to speak. I brought it out from the rare and first editions case. ‘It’s just uncanny, it really is,’ he said.

‘This woman.’

‘Yes! She said hello back like she knew me. I swear to god she called me by name!’

‘But I don’t know your name. Right? Mr G Ronan? I think you dreamt this.’

‘But it just happened,’ he said, like that explained something to him. ‘And you knew my name.’

‘Mr Ronan,’ I said, ‘I am one hundred per cent –’

I didn’t like the look in his eye. He began edging around the side of the desk, coming closer, and I backed away, but he lunged at me with a cry and grabbed me by the shoulders. Despite his size, I couldn’t hold him off and he backed me up, hard, against the first editions case. I heard the books behind me thud and tumble. ‘Take it off!’ he shouted in my face. With one hand, he tried to yank my hair from my head. ‘Take off the wig!’

‘Get back!’ I shrieked. I pushed against his forehead with my palm. ‘Get off me!’

‘Goddamn you, Mrs Mason!’ When a fistful of my hair wouldn’t tear off, he leapt up and stumbled backwards, his eyes locked on mine, but washed of rage. The blood had drained from his face. ‘Christ, that’s real!’

‘Yes! It’s real! See? Real hair attached to my own, personal head.’

‘Oh god.’

‘What is wrong with you?’

He grovelled to the other side of the desk. ‘Oh my god. I’m so sorry. I must be having another attack.’

‘Another attack! Of what? Do you want me to call an ambulance?’

‘I’ll be okay. I’m really sorry. I don’t know what came over me, Jean. Forgive me.’

That was the first time he had ever used my name. ‘You scared me. And you hurt me, you know?’ I began to feel the pain seep through the shock of being battered. ‘Are you sure I can’t call a friend or someone?’

‘No. I’ll go home and lie down. I’m just so sorry.’ He took his wallet out and put his trembling credit card down on the cash desk.

I tapped it for him. We stood together in a dreadful silence until I said, ‘Gilbert.’

‘No,’ he replied.

i like systems. order is good. I can pass a whole day in front of bookshelves alphabetizing, categorizing, subcategorizing. I look forward to shelving. I have the image, in my mind, of a beam of used books shining in through the door and through a prism in the middle of the shop. The beam splits and the books leap into their sections alphabetically.

I am the prism.

But alphabetical is not the only order. I’m not a library, so I don’t have to go full-Dewey. A bookstore is a collection. It reflects someone’s taste. In the same way that curators decide what order you see the art in, I’m allowed to meddle with the browser’s logic, or even to please myself. Mix it up, see what happens. If you don’t like it, don’t shop here. January to June I alphabetize biographies by author. July to December: by subject.

There are moral issues involved, too. Should parenting books be displayed chronologically by year of publication? I don’t want to screw someone’s kid up by suggesting outdated parenting advice is on par with the new thinking. Aesthetic issues: should I arrange art books by height to avoid cover bleaching? Ethical: do dieting books belong near books about anorexia? And should I move books about confidence into the business section? And what is Self-Help? Is it anything like Self Storage? (Which is only for things, it turns out.) In Self-Help, I have found it is helpful not to read the books at all.

And what about the borderline garbage that people like to buy – tales of clairvoyance, conspiracy books, fake science? I’m duty-bound to stock some of this stuff, but I like to put it on a higher shelf and force the customer to find the kick-stool. Take a moment to rethink your life choices.

I called Mr Ronan a few days later. I didn’t want to be nosy, but he’d left the store in such distress. I got his voicemail twice and left a message the second time. ‘Mr Ronan,’ I said, ‘it’s Jean Mason from Bookshop. I just wanted to ask you if you were feeling any better. I’m sorry for whatever fright you had, but I hope you’ve worked it out. Well. I guess I’ll see you next time. Bye.’

I put the phone away and at that exact moment a woman I would later be accused of murdering walked into my shop. She wore a green dress embroidered with tiny mirrors and had warm, buttery skin.

She browsed with her neck bent and looked sideways at me a couple of times through a drape of hair. She wasn’t really looking at the books. She was acting suspicious, like she was going to steal something. You can always tell the shoplifters. They act nervous until you make eye contact with them and then they act über cool, like they’re obviously the last person who would ever steal from a bookstore. ‘Can I help you?’ I asked her.

‘Maybe. Maybe not.’ She had a Spanishy accent. ‘Tell me, do you know who I am?’

Shit, I thought, another author. ‘Should I?’

‘I work in the Kensington Market. My name is Katerina.’

‘I’m Jean. I own this bookstore.’

She stood in front of the cash desk with her hands clasped in front of her. Her dress winked at me. The mirrors stitched onto it were the wings of butterflies. She folded her hands in front of her pelvis and took a deep, stagey breath. ‘If I call you out,’ she said gravely, ‘you must to come out.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘If I call you out, you must to come out!’

In downtown Toronto, you have to be prepared at all times to intersect with people living in other realities because they pop out at you when you least expect it. In the liquor store, in the lineup at Harvey’s, shouting about today’s god or just asking you whassup. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, ‘I really don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘I followed a rumour that there was a Llorona about. The Llorona of Ingrid. And if you are Ingrid’s Llorona, and I call you to come out, you must to come out!’

‘What the hell is a yorona?’

‘The Llorona cries for a lost child, and tries to steal one from its mother.’

Now she was beginning to scare me. ‘Are you serious? Are you accusing me of something? What do you think you know about me? We haven’t met before.’

‘I know.’

‘So?’

She kept her dark eyes locked to mine for a three-count. Then she relented. ‘Okay, Jean. So maybe you’re not Ingrid’s Llorona. You could be Sayona, but I don’t think so. You live near Kensington Market, Jean?’

The way Mr Ronan had acted seemed to be of a piece with this woman’s behaviour. I felt a need to see where she was leading. It was none of her business, so I lied. ‘I live around the corner from here, up a side street. Concord Avenue.’ I changed the name of the street, but I was honest about the neighbourhood. I also left out the words ramshackle and hut. It’s not like we couldn’t do better, but Ian says he’s not moving again for ten years. ‘If “near” is five kilometres, then I guess I’m near. But I never go to Kensington Market.’

‘Why?’

‘I don’t know. I have my local shops. I don’t have to go.’

‘You mean you don’t like to go, right? You think it smells bad?’ She leered at me. ‘Maybe you have a Llorona following you around.’

‘I want you to go now.’

‘Do you have children?’

‘I don’t,’ I lied.

‘Do you have a twin?’

Goddammit, what the hell was this? ‘No. I have a sister, but she’s older than me, and we look nothing alike. This Ingrid you’re talking about…?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘She is absolute your twin. Only her hair is shorter.’

‘Who told you you could find me here? You know Mr Ronan, don’t you?’

She gave me another galactic stare, her mouth clenched. She was very pretty, well dressed, smelling of some floral balm. ‘Who is Ronan?’

‘You might meet him in a waiting room one day. Anyway, if this is a joke, it isn’t funny. I know people will do anything to go viral these days, but I’m not falling for it.’

‘Is not a joke! You might have been an evil spirit. I called both Sayona and Llorona out of Ingrid and they did not come out. So now I know: I am witness a miracle.’ Her eyes welled up. ‘God bless the baby Jesus.’

‘Stop it. I’m sure she looks more like herself than she looks like me.’

‘No, no. You must come see now. She buys my pupusas!’

‘Your what?’

‘My pupusas!’

‘Katerina –’

‘Jean?’

‘The human face has millions of combinations. I mean, there’s Catherine Deneuve but there’s also Andre the Giant, right? But still we see people who look like each other all the time. It’s common.’

‘Who is Catherine Deneuve?’

‘A professional wrestler.’

She laughed. ‘You will see. You have Spanish books, by the way?’

‘I have some foreign-language back there,’ I told her. If she wanted to browse instead of leave, that was fine. As long as the conversation was over. ‘I have the Don Quixote Penguin in English.’

‘Don Quixote does not exist in English,’ she huffed, wagging her finger at me. She crouched in front of the poetry section. ‘And Catherine Deneuve was a old movie star.’

‘Humphrey Bogart was an old movie star. Deneuve is still alive.’

‘He was very ugly.’ She returned with a Celan. ‘She has exactly your eyes.’

‘Deneuve?’

‘Ingrid.’

‘Do you know her last name? Maybe I should look her up.’

‘Fox. F-O-…’ She had to draw the X in the air.

‘Really. Ingrid Fox.’

‘Maybe she will look you up.’

‘I hope she does!’ I said, with forced good nature. I spun her book around to face me and flicked the upper right-hand corner of the cover to see the price. ‘You’ll read German poetry in English, but not Don Quixote.’

‘Don Quixote thinks in Spanish. Is impossible to be any other way.’

‘Just take it,’ I told her. ‘A gift. It’s been nice meeting you.’

‘Really?’

‘No, but I want to give Torontonians a good name.’

‘This is a wonderful city, but it is cold. Weather and people.’

‘We don’t mean to be. We’re just shy.’

‘No, you’re just boring. But you are very good and nice. Hey, I bet you don’t think I can do Bogie.’

‘It hasn’t occurred to me to wonder.’

She tightened her jaw. ‘I come to Casablanca for some water,’ she said.

It wasn’t bad.

in the spring of 2014, I chose a location for Bookshop out on the revamped part of Dundas Street around the top of Trinity Bellwoods Park. I saw coffee shops springing up and decided to cast my lot. Now we have artisanal cheese shops, a pet store, and some good restaurants. And Ossington Avenue. Ten years ago the only nightlife on Ossington was drive-by shootings. Now you can get Italian shoes and chocolate for wine tastings.

We’re only in Toronto by a lucky stroke. If not for Ian having had some good fortune playing marijuana stocks on the TSE (husband: ‘Skill!’), I’d still be working at the college in Port Dundas; he’d still be in the Ontario Police Services. We’d all be back in that quiet, safe little town. But as my ex-cop likes to say, ‘I smelled the coffee on the wall.’ The country was going to legalize pot. He’d busted some growers in Westmuir so many times he’d become friends with them, and some were liquidating in the lead-up to legalization to buy stocks instead of plants. Ian didn’t warn me that he was retiring and putting all of our savings into stocks with names like Gemini Pharma and GreenCo. Luckily for him and us, it was a good bet, although I was furious not to be consulted.

Every place you live has its own rhythms, and it can take a while to get used to it or fit in. After two years, I was still decoding Toronto, and I certainly knew what Katerina was talking about – the friendly coldness of Torontonians – but many things about the city were becoming clearer. Torontonians wanted to get on with it, but they were generally courteous. If someone let you into a car lane, for instance, you were expected to wave with casual gratitude, like you expected it, but thank you anyway. Toronto’s panhandlers say thank you when you give money, and also when you say ‘Sorry.’ In fact ‘Sorry, thank you,’ may be the most common exchange between citizens. Toronto’s reputation when I lived outside it was that it was a steely, arrogant place without a heart, but now I see it likes outsiders and it draws on a deep spring of weirdness. Maybe that’s the source Katerina came from.

I dwelled for a while on these two encounters in my shop and then, to satisfy my curiosity (or to have my gullibility further tapped), one day mid-month I closed the store early and went down to the market. Apart from our move, nothing as interesting as Katerina and her Ingrid had happened to me in a long time. I planned to keep the whole thing to myself, because Ian is a worrier and this was only a lark. Who wouldn’t want to know what was going on? And a part of me was thinking: what if this turns out to be a good story?

May was on its way, thank god. We were getting inoculations of sun. Winter here arrives, stays, persists, goes away a little, then comes back and people start leaping off the bridges. That’s approximately March, when jumping is at its apogee, but even then, winter isn’t over. What it likes to do is go away for a week in April and then return for three days and finish grandpa off.

Katerina hadn’t said where she worked, but Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market was crowded with Mexican, Chilean, Middle Eastern, and Portuguese businesses. I looked for her in all of them. The last time I’d been in the market – years ago – its identity as a countercultural space had already been scrubbed clean. It was a hodgepodge now, but something was happening: it was young like it had once been, the coffee was excellent, and I saw a couple of restaurants I’d risk eating in. The smell of weed hung in the air, advertising the dozen or so medical marijuana dispensaries that had appeared since the Liberals were elected.

No matter your approach, once you crossed College Street or Spadina Avenue or Dundas, you were somewhere else when you entered Kensington Market. It’s like if I cross the Canadian border in my car, I know I’m in the United States. Even before the signs for Cracker Barrel come up, I’m feeling hustled. Kensington Market’s energy was hustle too, plus bustle, a lot of movement right in front of your eyes, and a shudder or rattle behind it. Countercultural, but bloody and raw. The organic butcher beside a row of dry-goods shops offered, in one window, white-and-red animal skulls with bulbous dead eyes, and in the other, closely trimmed racks of lamb and venison filets, displayed overlapping each other like roofing tiles. Then some stranger rustles past with blood on his cheeks.

There was no sight of Katerina on Baldwin Avenue, either. It had been about a week since she’d appeared in my store, and I wasn’t entirely sure I remembered what she looked like. I’ve had this problem before. When I first meet someone, my mind must be busy noting other details, because I don’t always register what they look like. Sometimes I even forget the faces of people I know. There have been times when I haven’t been able to bring my own sister’s face to mind. Not even if I look at one of the few pictures I have of her. I’ll look away from her image and close my eyes, but she won’t be there.

Katerina was not on the lower part of Augusta Avenue. I looped back and forth over the street, going into a fish and chips shop, a vegetarian wok spot, the coffee corner, and looking at the people behind the counters, sometimes searching their faces as if a person I spent ten minutes with not very long ago could change that much. On Augusta I crossed with throngs of every station back and forth and back over the street.

I found her at last, working a flattop in a Latin American food court. The only sign over the entrance said CHURROS CHURROS CHURROS. Seven or eight food stalls went back inside the narrow space. In the front window, an elderly man squirted batter into a decapitated three-gallon jerry can of boiling oil. Brand name Cajun Injector.

‘How are you!’ Katerina came around her counter to hug me. I stiffened in her embrace. ‘Are you okay? I worried about you, you know.’

‘About me?’

‘Of course! Come in the back, I make a coffee.’ She ushered me toward the rear of the food mall more quickly than necessary, I thought. I smelled coconut and coriander as we went past the stalls. ‘Miguel won’t be happy to see you after what you did.’

‘What I did?’

‘Yeah! Did you go to the doctor?’

She walked into my back.

‘Katerina,’ I said, ‘I’m Jean. Who do you think I am?’

‘Jean!’ she said. ‘So stupid of me. You are the other one!’ She admired me. ‘Incredible.’

‘I’m the other one now?’

‘I thought you didn’t believe.’

‘I don’t know what I’m not believing in. What did Ingrid do? Why did she have to see a doctor?’

Katerina showed me to the patio. ‘We talk out here. Are you hungry? I have to look busy a couple minutes.’

‘I’m not hungry. Just hurry.’

‘Go sit.’

I hesitated, or resisted, but then I obeyed. At the back of the building, a red rusted VW Bug stood on blocks, and behind it, in a garage partially closed off by tarps, I heard voices and smelled weed again.

In one of the chairs, my legs sprawled out in front of me, I laid my head back and closed my eyes. Now I felt stupid. I was almost certain that Katerina wasn’t a threat, but between her and Mr Ronan – who had not returned to the shop – I probably should have started to get a little suspicious. Something was definitely wrong, but what? When I opened my eyes, the clouds had amphibious underbellies and were ringed in a menacing shade of grey. I leaned forward and looked into the food mall, but it was too bright to see in.

I got up and left the patio. This was foolish. I walked partway back to Augusta Avenue along the alley and stopped. I stood with my back against the wall. I imagined I could feel the graffiti skirling out in twisted bands behind my shirt like tentacles of smoke.

‘You want to eat in the alley?’ Katerina said. She stood at the edge of the patio with a styrofoam plate of food in her hands. I returned to the table. I didn’t know it yet, but by returning to the patio instead of walking away, I had sealed Katerina’s fate.

She put the plate down in front of me with an orange Jarritos. There was an albino hamburger on the plate that smelled the way my grandmother’s kitchen sometimes smelled: of comfort. ‘This is called the pupusa,’ she told me. ‘You eat it with your hands. Like a sandwich. Go on,’ she said, ‘eat it.’ I tried to figure out how to pick it up. ‘And because you weren’t listening the first time, I will tell you again about the Llorona and the Sayona.’

‘It’s not necessary,’ I told her, but the moment I’d taken a bite of her pupusa, I didn’t care anymore. Its scent was how it tasted. The shell contained a mixture of avocado, white cheese, corn, and a greeny-brown salsa that tasted like roasted tomatoes and garlic. The shell was made of white cornflour; the hot and crispy-hard surface perfectly burnt in a few places, and it was warm and bready on the inside. Katerina grinned at my pleasure, and I concluded that, at the very worst, she was only a nuisance.

‘So,’ she said. ‘My mother has told me I was visited by a Llorona myself. When I was a baby. An old woman was coming to the house one night to ask for a cigarette. My mother gave her one. The old woman comes back two more times, and she doesn’t want to be rude, my mother, so she brings her into our house. She makes her tea and the old woman tells she has a daughter my mother’s age and my mother feels warm toward her. After that, she comes and visit from time to time, always after I go to sleep, and my mother was smoking with her and making her hot tea and sometimes a tortilla with a egg inside it.

‘One night, the old woman wants to use the anexo. To make her water. My mother show her out back. She tells me that the old woman went away for too long and she felt something was going on. So she goes to my room, and my door is open. She goes in and she sees a woman who look exactly like her! Standing beside my crib! And I am inside the crib, standing, reaching to her, who I think is my mother. My real mother, she shouts and stamps her feet and the spirit goes out through the curtains! Straight out the wall. My mother picks me out of my crib and holds me the rest of the night.’

‘How do you know she was your real mother?’ I asked, trying to make her smile. ‘Maybe it was a bait-and-switch-and-bait.’

‘She was never visit by the old lady again. Later, her mother, my grandmother, tells her who it was. The Llorona! Sometimes she comes to visit crying with a baby in her arms, sometime to see if a baby is in the house. If she come in three times, then she will try to take!’

I chewed calmly. ‘This is delicious, by the way.’

‘Now you see what we are dealing with, you and Ingrid.’

‘I thought you concluded neither of us were Guatemalan spirits.’

‘There are more than two spirits,’ she said. ‘I have not ruled out for Ingrid that she is La Siguanaba.’

‘Speaking of Ingrid, why did she go to the doctor? Did she try to walk through a wall or something?’

‘You are joking.’

‘A little.’

‘I can make you believe,’ she said, and her tone of voice made me want to jump up and run. She leaned over the table and tucked her hair behind her left ear, revealing three blue dots tattooed on her temple. A triangle of pinpricks still red and raw around the edges. ‘Look at this. She give these to me.’ The dots gleamed like spider eyes.

‘What is it?’

‘A trick with a sewing needle!’ Katerina laughed and fell back into her chair. ‘I invite her over one night! We have some drinks. She’s a good talker. She was drunk. She tells me…’ She lapsed into silence and a trickle of blood came out of her hairline. ‘She said she was sick. Here.’ She tapped her head, right on the tattoo, and noticed the blood on her fingertip.

‘I think you scraped it with your nail.’ I passed her a napkin. ‘Why did you let her do that to you?’ I asked. ‘What does it mean?’

‘We get drunk and she give me a tattoo. Big whoop.’

‘Jabbed you in the temple three times for the hell of it.’

‘It means therefore, she says.’ She looked at the blood on the napkin.

‘Therefore.’

‘She says it is my own personal therefore. I think she fell in love with me.’

‘Wow. Do you usually drink so much?’

‘Yes.’

‘And that night?’

‘Of course. What do you think? I do anything for company here. I think maybe Toronto is a fuckless city. It was nice that she come over. But you have to be careful, if you ever meet her, don’t believe everything she say.’

‘Like what?’

‘She thinks she has a doppelganger!’ She laughed and I suddenly felt really scared. My heart hiccupped behind my ribs.

‘This was great, Katerina. How much do I owe you?’

‘You should go to the park,’ she said. ‘That is where she will come. One day again soon.’

I struggled for a moment over whether I really wanted to know. ‘Which park?’

‘Her again?’ said a man in the doorway. He wore a white apron stained with chocolate sauce.

‘No. Another one! See?’

‘Hello,’ he said to me. ‘You pay on the way out.’

‘It’s on me,’ Katerina said.

He switched to Spanish and harangued her. It was obvious they were, or had once been, lovers. But he was also the boss.

‘I’m allowed to do nice things for people,’ she said in English. ‘Miguel was a mathematician in Chile,’ Katerina explained to me. ‘But here he is only Churros Churros Churros.’

For that, he came out and grabbed her by the arm. I was on my feet before I knew it. ‘Let her go! Let go of her right now! We don’t grab people!’

‘She owes me four hundred dollars.’

‘I’ll give you the money,’ I said. ‘Let her go.’

Katerina came and stood beside me. She rubbed her upper arm. ‘You don’t have to do that. I don’t owe him anything. Ingrid owes him.’

Miguel said: ‘She dented the flattop with a cast-iron pan!’

‘Ingrid?’ I asked. ‘You’ve seen her, too?’

‘Who? This one!’ he said, pointing at Katerina. ‘Miss Hot-and-Cold!’

‘And he makes fun of my English!’ she said, and started to cry. ‘Shithead. I break up with him because he is so mean. And a sucio cerdo, a pig, a dirty pig!’

‘You go,’ he said to me.

Katerina tapped her tattooed temple. ‘Don’t worry. I don’t belong to him. I am with you and Ingrid, miracle women, and you protect me.’

‘I’m a witness,’ I warned him, sliding past. ‘Don’t touch her again!’ To Katerina, I said: ‘I’ll come back soon. I wrote my phone number on the napkin.’

the park katerina meant is called Bellevue Square. I saw what she was talking about right away: you could see anyone or anything in that park. I sat on one of its benches after leaving the food mall and watched people coming and going for two whole hours. I had to remind myself to keep looking for my twin, but the passing parade was so gripping that from time to time I forgot my stakeout. The park was a clearing house for humanity. I saw no sign of my lookalike.

The following week I went back, and the week after, too, a couple more times. I walked through the square, or sat for an hour, sometimes two. For cover, I had one of those puzzle magazines full of sudokus and crosswords, and I occupied myself with filling them in when I wasn’t doing my regular sweep of the park. I figured out which restaurants would let me use the washroom, which store sold the cheapest water. As my main lookout point, I settled on the low wall that half encircles the playground on the north side of the square. It gave me a vantage to the south as well as both sides of the park, and I could easily scan the path that cut it in half diagonally, southwest to northeast.

I found reasons throughout the second half of April to drift toward the park, or pass the park, or sit in the park. There were times when I was at home or in the store when I felt a need to go there. And other times, I sat on the low wall overcome with a feeling of wrong, as if I were forgetting something important, or being watched myself. It wasn’t anxiety. It was something that was present everywhere all at once: a climate. Something I was in.

At the very beginning of May, I started buying my groceries in the market, too. That gave me extra days to have a reason to go. The temperature shot up into the twenties, and the park swelled with people and animals and garbage. I began to count the number of people who weren’t Ingrid, and I kept track of them on my phone, giving every person an identifying name so I wouldn’t count them twice, like Earlobe Mole and Triple Sweater Man and Bendy, who was a woman whose head sat askew on her neck and who walked serpentine.