Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Sheep Detective Novel

- Sprache: Englisch

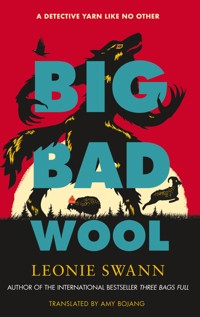

A flock of sheep graze on the edge of a peaceful French forest. But these are not your average sheep and, in reality, the setting is far from tranquil. While the herd are the cleverest you will ever encounter, thanks to their shepherds' regular bedtime stories and previous testing of their detective skills, they are unprepared for a fresh threat. Several sheep have recently disappeared, and other creatures have fallen prey to a shadowy figure. The theory of a werewolf might be just a wild fairy tale, but when a human is killed, it becomes clear that even fantasies can be fatal. Miss Maple, Mopple and the rest of the flock, with the help of their goat neighbours, follow the werewolf's trail in a desperate attempt to stop the killings with sheep logic, courage, and concentrated food.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 490

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

BIG BAD WOOL

LEONIE SWANN

Translated from the German by Amy Bojang4

Contents

DRAMATIS OVES

DRAMATIS CAPRAE

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

DRAMATIS CANIDAE

PROLOGUE

Over and done with it.

It was always nice afterwards.

He liked to just stand there, leaning on a tree listening to the thrill of the chase seep into the snow. Like blood. The sky and the rush of the forest above him, the ground beneath him. Surveying the scene in front of him.

Everything was so peaceful. No fear. No hurry. He felt free. Newly born. Surprised to have hands – they were so red – and legs and a body.

During the hunt everything felt so disembodied; there was just a front and back, tracks and prey and speed. Life and death. Four legs or two? It didn’t matter. And sometimes they got away. Rarely. That was a good thing. All was well.

A robin landed on a branch. So pretty, so close, so alive. He loved the forest. No matter what had happened, no matter what might happen, the forest took him in, and he became an animal 12like all the other animals. If it had been nighttime, he would have howled at the moon out of sheer joy.

But it wasn’t nighttime, and that was a good thing too. It was broad daylight, and the colours shone.

And time was slipping away.

He sighed. The time afterwards was always too short.

He would soon start to freeze. He had to go back. Wash his hands white in the snow. Put on some gloves. A different pair of boots. Double back. Cover his tracks. Start thinking again. About groceries and tax returns and about her, of course. Always her. About the things humans think about.

He needed to take a suit to the cleaners. He had run out of aftershave. A plant in his bedroom was looking a bit sad. Maybe it needed watering? He didn’t know much about plants. He had work to do. And he needed to have lunch. Mushrooms fried in butter and fresh bread! Some crusty bread would be nice.

He took a final look at the scene in front of him – the fox again! The fox was an interesting accent – then off he went, on his two legs, changing a little with every step.

He couldn’t help but smile as he stepped out of the forest. Sheep! The chateau looked so much more interesting with snow and sheep. They were so white – all except one. The black sheep put him on edge.

He carried on along the fence towards the chateau, surreptitiously seeking out her window. He couldn’t help it.

Nothing.

Deep inside him the creature curled up into a sated, contented little ball and went to sleep.

1

THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS

‘And then what?’ asked the winter lamb.

‘Then the mother ewes brought them to safety, away from the man with the little dog. And they found a … a …’ Cloud, the woolliest sheep in the flock, was at a loss.

‘A haystack!’ Cordelia suggested. Cordelia was a very idealistic sheep indeed.

‘Yes, a haystack!’ said Cloud. ‘And the mother ewes ate while the lambs rolled in the hay – and fell silent!’

The sheep bleated enthusiastically. The repeated telling of the story of The Silence of the Lambs had resulted in a few changes, and it had gained a little something each time.

Rebecca the shepherdess had read the book to them in the autumn when the leaves were already yellow, but the sun was still round and ripe and robust. The sheep could no longer say why the book had given them the creeps back then, during those first cold silvery autumn nights. Only Mopple the Whale, the fat memory 14sheep, still remembered that hardly any lambs, and precious little hay, had featured in the book that Rebecca had read to them on the sun-warm steps of the shepherd’s caravan.

The wind drove wisps of snow between their legs, the bare branches at the bottom of the meadow fence shivered and the story was over.

‘Was it a big haystack?’ asked Heather, who was still young and didn’t like it when stories ended.

‘Very big!’ said Cloud confidently. ‘As big as … as big as …’

She looked around for something big. Heather? No. Heather wasn’t particularly big for a sheep. Mopple the Whale was bigger. And fatter. Bigger than all of the sheep was the shepherd’s caravan standing in the middle of their meadow, even bigger than that was the hay barn and biggest of all was the old oak growing on the edge of the forest that had shed countless crunchy, bitter brown leaves in the autumn. It had been a devil of a job grazing around all of those leaves.

Flanking their meadow was the orchard to the right, and the goats’ meadow to the left. Behind the two meadows was the forest, strange and susurrant and far too close; in front of them the yard with stables and dwellings, smoking chimneys and humans making a racket; and right next to them, close and grey and solid as a pumpkin, the chateau. The slight incline up to the forest gave the sheep an excellent view of it.

‘As big as the chateau!’ said Cloud triumphantly.

The sheep marvelled at the size of the chateau. It had a pointy tower and lots of windows and blocked the sun far too early each evening. A haystack would have made a welcome change.

Something made a bang. The sheep gave a start. Then they craned their necks curiously.15

Something had been chucked out of the window of the shepherd’s caravan. Again!

The flock launched into action. Quite a few Things had been chucked out of the shepherd’s caravan just recently and sometimes they turned out to be interesting. A pan of only slightly burnt porridge for instance, a houseplant, a newspaper. The houseplant had made them feel bloated. Mopple was the only one who had enjoyed the taste of the newspaper. Today wasn’t a bad day: in front of them in the snow lay a woolly jumper. Rebecca’s woolly jumper. The woolly jumper. The sheep liked this jumper more than all the others. It was the only item of clothing they understood. Beautiful and sheep-coloured, thick and fleecy – and it smelled. Not just vaguely of sheep like most woolly jumpers, but of certain sheep. Of a flock who had lived by the sea, grazed on salty herbs, trodden sandy ground, breathed well-travelled winds. If you sniffed very carefully, you could even make out individual sheep. There was an experienced, milky mother ewe, a resinous ram and the scraggy shaggy sheep from the edge of the flock. There were dandelion and sun and seagulls calling in the wind.

The sheep drank in the jumper’s woolly aroma and sighed. For their old meadow in Ireland, for the vastness and the grey thrum of the sea, for the cliffs and the beach and the gulls, and even the wind. It was quite obvious by now: the wind was supposed to travel – sheep were supposed to stay at home.

The door of the shepherd’s caravan opened and Rebecca the shepherdess stomped angrily down the steps, her lips pursed. She retrieved the jumper from the snow, bringing their pleasure in the comforting aroma to an abrupt halt.

‘That’s it!’ she muttered, frowning dangerously and brushing 16snow crystals off the knitted wool. ‘That’s it! I’m chucking her out! This time I really am going to chuck her out!’

The sheep knew better than that. All sorts of Things were chucked out of the caravan, but not her. She barely moved at all, but when she did, she was surprisingly quick. The sheep doubted she would even fit through the window of the shepherd’s caravan.

Rebecca seemed doubtful too. She looked down at the jumper and sighed deeply.

A familiar face appeared in the milky glass of the caravan window, strangely soft-edged and wide, staring disapprovingly down at Rebecca and the sheep. Rebecca didn’t look up. The sheep stared back, fascinated. Then the face had disappeared again and the caravan door opened. But nobody came out.

‘From now on, that stinking thing stays out of the house!’ came a moan from the caravan.

Rebecca took a deep breath.

‘It’s not a house, Mum,’ she said in a perilously quiet voice. ‘And it’s definitely not your house. It’s a caravan. My caravan. And the jumper doesn’t stink. It smells of sheep! That’s normal when it gets wet. Sheep smell like sheep when they get wet as well! Sheep always smell like sheep!’

‘Exactly!’ Maude bleated.

‘Exactly!’ the other sheep bleated. Maude had the best nose in the whole flock. She was well-versed in smells.

An icy silence drifted out of the shepherd’s caravan. ‘And they don’t stink!’ Rebecca hissed. ‘The only things that stink around here are your …’

She broke off, sighing again.

‘Little bottles!’ Heather bleated.

‘And the goats!’ Maude added for the sake of completeness. 17The sheep could sense the silence in the caravan condensing into a little dark cloud. And the cloud was thinking.

‘Who cares?’ Mum shrieked. ‘I don’t care if they smell of sheep! They can spend all the livelong day standing around smelling of sheep out there! But not in here. Sheep have no business being in here!’ Her voice softened. ‘Really, Becky, all I’m asking for is some basic hygiene!’

Hygiene didn’t sound like a bad thing. A bit like fresh, green, gleaming grass.

‘Hygiene!’ the sheep bleated approvingly. All apart from Othello, the new jet-black lead ram. Othello had spent his younger years in a zoo, where he’d seen – and above all smelled – a few hygienas from a distance and knew that they were nothing to get excited about. Not in the slightest.

Rebecca lowered her hands, and a jumper sleeve that she’d only just lovingly cleaned landed back in the snow again. She looked lost, a bit like a young ram who didn’t know whether to run away or attack.

‘Attack!’ Ramesses bleated. Ramesses was a young ram himself, and usually plumped for running away.

Rebecca lowered her head, crumpled the jumper to her chest and puffed herself up. She wasn’t particularly big. But she could make herself very big when she wanted to.

‘This is my caravan. And they’re my sheep. And this is my jumper. And nobody here needs your permission to smell of sheep. And I don’t need your advice. Dad left me all of this because he trusted me, and d’you know what? I’m not making a bad job of it!’

The sheep could sense something in the caravan changing. The cloud expanded, getting clearer and wetter. Then it started to rain.18

‘Your faaather!’ Heather whispered into Lane’s ear.

‘Your faaaaather!’ came a groan from the caravan.

‘Great. Well done, Rebecca!’ muttered Rebecca.

The shepherd’s caravan sighed deeply, then Mum appeared in the door. It didn’t look like she was just standing there. It looked like she was stuck to the doorframe like a rather elegant slug, neat and brown and gleaming. Water was running out of her eyes, blurring her face.

The sheep looked at her, unsettled.

By now the sheep were convinced that Mum had brought the rain, in her ocean-blue handbag perhaps, or maybe in her little shiny metal case, possibly even in the pockets of her immaculate coat. The rain had been her ally when she had knocked on the door of the shepherd’s caravan – the rain and homemade sloe gin.

Rebecca had opened the door, and Mum’s words had begun to patter down: longing, daughter, what sort of backwater was this, from now on I’m only flying first-class, daughter, worried, only for the holidays, you look thin, and I brought you some sloe gin.

Rebecca’s arms had drooped. ‘Mum!’

It hadn’t exactly sounded welcoming, but Mum and the rain had stayed all the same. It hadn’t rained at all before that, not for the entire autumn – at most a thundery shower that made the frogs in the chateau moat croak with delight. That was it.

From then on there was nothing but rain. It dripped in the hay barn. The ground was muddy and slippery, especially down at the feed trough. The concentrated feed tasted damp. The little stream on their meadow was now a brown torrent, and Mopple the Whale had fallen in while hunting down a riverbank herb.19

‘Panta rhei,’ said the goats at the fence.

First it rained. Then it snowed. Then the sloe gin was chucked out of the window. It wasn’t particularly slow. Some other Things followed. Some of the banished items were fetched back into the caravan by Rebecca, some by Mum and some by nobody, and Mopple ate the newspaper and that night he dreamed about a human with a fox’s head.

It was all connected somehow – but the sheep didn’t know how.

‘It’s got nothing to do with Dad,’ Rebecca said, softly this time, putting on the jumper. ‘It’s about you and me. You’re a guest here, and I want you to act like a guest. That’s all. Okay?’

‘Okay,’ Mum snivelled, dabbing her eyes with a white cloth.

‘Okay!’ the sheep bleated. They knew what was coming next: cigarettes. Mum on the caravan steps, Rebecca a bit farther up the hill, leaning on the wardrobe that, for some unknown reason, resided under the old oak.

Smoke and silence.

The sheep were silent, too, scraping in the snow, grazing damp winter grass or at least acting as if they were. They were all waiting for something that was about to happen. Something you might not be able to see, but could definitely smell.

There was a strange sheep on their meadow. He had been there before them, not on the sheep’s meadow, but in the apple orchard and on the narrow strip of pasture between the meadow and the edge of the forest. Now he was in with them and spent day after day loitering about near the fence. Whenever Rebecca leaned on the wardrobe smoking, the strange ram froze. He didn’t move a muscle, not an ear, or an eyelash, not even the tip of his tail. But he smelled. Smelled of purest, blindest panic.

The whole thing made the sheep nervous.20

In general, the strange ram wasn’t a fearful sheep. He wasn’t scared of Tess, the old sheepdog who spent most of her time sleeping on the steps of the caravan. Nor was he scared of Othello’s four black horns. But he was scared of Rebecca when she leaned on the wardrobe smoking and looking out across the meadow. He was scared senseless.

Finally, Rebecca stubbed out her cigarette, carefully put it in her pocket and walked back down towards the shepherd’s caravan. The strange ram relaxed and started muttering to himself. The other sheep waggled their ears and tails in an attempt to shake off the silence.

The strange ram got on their nerves. He didn’t really smell like a sheep and what’s more, he didn’t look like a sheep either. More like a big, cumbersome moss-covered stone.

Miss Maple, the cleverest sheep in the flock and maybe even the world, claimed he was a sheep all the same. A lonely sheep that nobody had shorn for years, with a great mass of stiff, felted grey wool on his back – and a story that nobody knew. He was amongst them, but not with them, he was running with a flock, but not their flock. Sometimes they got the feeling that the strange ram couldn’t see them at all. He could see other sheep though, sheep that nobody else could see.

Ghost-sheep. Spirits.

The real sheep didn’t look at him. Apart from Sir Ritchfield.

‘I think … it’s a sheep!’ Ritchfield bleated excitedly. The old lead ram was currently taking a keen interest in the question of who was a sheep – and who wasn’t.

The others sighed.

Yet again they were wondering if the trip to Europe had really been such a good idea after all.21

They had inherited the journey from George, their erstwhile shepherd. One day he had just been lying lifelessly on their pasture, pinned to the ground by a spade. The sheep themselves had had nothing to do with it – well, not that much anyway – but they had inherited a trip to Europe and the shepherd’s caravan, and along with it came Rebecca, George’s daughter, who had to feed them and read aloud to them. It was in the will.

But then there must have been some kind of mistake. The Europe George had told them about was full of apple blossom, with herby meadows and peculiar long bread. Nobody had said anything about honking cars, dusty country lanes and buzzing gnats, nothing of snow and ghost-sheep, let alone goats.

The sheep blamed the map. Rebecca had brought a colourful map that she spent inordinate amounts of time constantly gazing at during their travels, and the map evidently knew nothing about Europe.

Three sheep had distracted Rebecca in a meadow of sunflowers while Mopple the Whale had snatched the map from the steps of the caravan, and eaten it in its entirety, even the hard shiny bit made of card. And sure enough: a woman had turned up a few days later, her hair severely scraped back, full of flattery, offering the sheep somewhere to stay. Before long they’d said goodbye to the exhaustion of travelling life and had a meadow again, a hay barn, a feed store and this time even a wardrobe. But it wasn’t their meadow.

‘Remind me why we’re here again.’ Mum sighed, smoking her second cigarette, still stuck in the doorway like a slug. Tess had managed to squeeze past her and was greeting Rebecca on the steps of the caravan, her tail wagging. Rebecca crouched and scratched Tess behind the ears. Tess tried to stick her greying muzzle into Rebecca’s armpit.22

‘I’m here because the sheep need somewhere to overwinter,’ Rebecca said. She had already explained it a hundred times, first to the sheep then to Mum, sometimes to herself as well. ‘The pasture’s good; the rent’s cheap. It’s idyllic. I was asked. Why you’re here, I don’t know.’

The sheep knew why Mum was there: she was a parasite. Rebecca had secretly told them once while she was giving them their hay. ‘She acts like she’s well-to-do, but she’s broke. Hardly surprising given her job! So, she throws together some sloe gin and holes up here for weeks on end. Just for the holidays? Pah! You’ll see. I’ve got no idea how I’m going to get rid of her.’

Not through the caravan window, that was for sure. Mum blew smoke down at Rebecca and Tess, eyeing the chateau critically.

‘We should get out of here. Look around you, darling! Look at this godforsaken place – not to mention all the nutters.’

‘Hortense is all right,’ Rebecca said.

‘No style,’ said Mum with contempt. ‘I thought French women were supposed to have style. What’s the deal with the goatherder over there? He spends the whole day wandering through the forest and doesn’t say a word when he walks past. It’s just not normal! Have you noticed the way the others keep their distance from him? There must be a reason for it.’

‘They keep their distance from us too,’ Rebecca said.

Tess had rolled onto her back and was getting a belly rub from Rebecca.

‘There’s a reason for that,’ Mum said. ‘You don’t understand people, Becky. Just like your father. You’ve never been interested in people. I always have been. I’ve got the sense. I can see. Idyllic? The cards say something quite different!’

The sheep cast meaningful glances at one another. Card Things 23often said something different. Like the shiny map made of card, until Mopple had eaten it. All of their problems had started with the map.

‘Do you know which card has been turning up in all of my séances for the last two weeks?’

Rebecca sighed, standing back up and stretching like a cat. ‘The Devil!’ the sheep bleated in chorus. It was always the same.

‘The Devil!’ Mum screeched triumphantly from the steps of the shepherd’s caravan.

Rebecca laughed. ‘That might be because you have three Devils in your deck, Mum. And you took out Justice and Temperance!’

Tess did a doggy stretch and slipped past Mum’s slippers, back into the caravan.

‘And? The cards just have to be adjusted a bit to suit modern life, that’s all. Since I removed Temperance, my success rate is seventy-five percent! Do you know what the others …’

Rebecca waggled her hand back and forth as if she were shooing away invisible – and very cold-hardy – flies, and Mum sighed.

‘Be honest, darling, do you really feel comfortable here?

When he comes tomorrow, ask the v—?’

Quicker than a fox, Rebecca darted up the caravan steps and put her hand over Mum’s mouth.

‘Are you out of your mind?’ she hissed. ‘Do you have any idea what will happen if you say that word? It’ll be like unleashing the devil!’

‘The devil!’ the sheep bleated.

If anything was going to be unleashed around here, it was usually the devil.

24That evening the sheep spent longer than usual standing in front of the hay barn looking out into the night. The yard buildings nestled up to the chateau, seeking refuge. The apple orchard was silent. The smell of smoke and new snow was in the air. The shadow of an owl glided soundlessly over the meadow towards the forest.

Did they feel comfortable here? Cloud maybe. Cloud was the woolliest sheep in the flock and she felt comfortable anywhere. Wool and comfort went together. Sir Ritchfield seemed to like it too because there were lots of conversation partners who didn’t run away: the old oak, the wardrobe, the stream, sometimes the unshorn stranger, and if he was lucky, a goat or two. In fact, Ritchfield’s loud and one-sided conversations were rather popular with the goats, and quite often a whole gang of them gathered at the fence, giggling and gambolling.

The others weren’t so sure. Something wasn’t right. A single forgotten apple still hung in the orchard, red as a drop of blood. You could see it, but not smell it. Maybe it was time to eat some more card, so that they could move on. But what sort of card?

‘What was she about to say?’ Miss Maple asked suddenly.

‘Who?’ Maude asked.

‘Mum,’ Maple said. ‘Before Rebecca covered her mouth.’

The sheep didn’t know and fell silent. A crescent moon hung over the meadow like a nibbled oatcake.

‘Rebecca seems really panicked,’ said Miss Maple. ‘As if something’s about to happen. Something terrible.’

‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ said Cloud, fluffing herself up.

‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ the other sheep bleated confidently. Every day there was concentrated feed in the trough 25and they were read to on the steps of the shepherd’s caravan. If the drinking pool was frozen over, Rebecca hacked through the ice with a pickaxe. If it snowed too much, they stayed in the hay barn. If they were bored, they ate or told stories. And awaiting them at the end of every story was a fragrant haystack.

The sheep looked out at the blue snow and felt like they could take on anything.

At that moment a sound cut through the silence, long and thin, distant and heart-wrenching.

A wail.

A howl.

2

CLOUD DISAPPEARS

Cloud was flying.

Not swaying majestically like a cloud-sheep as she did in her dreams; more like a dandelion seed, zigzagging back and forth with the changing moods of the wind. Straight across the meadow, over slushy snow and grass that was frozen solid, in a high arc over the stream, past the old oak – sparrows scattering – and up the hill.

Her legs were galloping frantically below her. Her ears were thudding. Her heart was fluttering in the wind. Faster! She’d left the others behind ages ago, but not him. He was right behind her, hard on her heels, an ominous glint in his eye.

The wind blew Cloud towards a swaying forest. Between the forest and the meadow was the fence.

It was always there, but for some reason Cloud hadn’t reckoned on it today. Her eyes darted in all directions, panicstricken. Left along the fence into a corner? Right along the fence into a corner? The wind had other plans.27

Without so much as taking a breath, Cloud galloped headlong into the wire.

A ringing in her ears, a dull ache in her neck. The fence yielded. One of the posts connecting the wires fell over. The sky toppled over.

But the next moment Cloud was back on her hooves and she turned her head. Her pursuer was panting up the hill, just a few sheep’s lengths away. But the fence now lay flat in front of her, and she jumped over it. Another jump to the edge of the forest. Another and she was in the forest.

Suddenly, the rushing in her ears had stopped. Cloud was shivering. She felt as if she didn’t have a single strand of wool left on her body. Completely naked. Absolutely freezing. A little bird landed on a branch high above her, and snow dusted down.

Cloud shuddered and cautiously trotted on.

Soon the half-dark of the forest enveloped her like a barn, and the panting had gone.

A snap here, a snap there, but otherwise silence. Maybe it was all just a dream after all.

The other sheep had watched Cloud’s flight with mixed feelings.

On the one hoof, they were happy that the vet hadn’t caught Cloud. On the other, they were next. One of them. Then another. And another. All of them eventually. The vet would hold them so tightly that they wouldn’t be able to breathe for fear. He would hurt their hooves and their ears. He would stab them with a needle and pour foul, bitter liquid into their mouths. The vet was the most dangerous creature they knew. Now he was standing at the edge of the forest, his arms hanging limply at his sides, staring intently after Cloud.28

Rebecca swore. She pushed her red woolly hat out of her face and scowled at the sheep. ‘Stay there!’ she hissed.

As if the sheep had a choice! Rebecca had shut them all in the pen. The pen was nothing more than a narrow and actually very well-liked piece of meadow – the piece of meadow with the feed trough on it. But sometimes Rebecca shut a gate, and then they were trapped, crowded together, shoulder to shoulder, right down at the yard fence, where the most humans went by. Why Rebecca insisted on always doing things with the vet was a mystery to the sheep.

Now the shepherdess was running up the hill, infinitely more elegantly than the vet, if not quite as elegantly as Cloud. The vet said something and opened his arms wide, as if to catch Rebecca. She shook her head. The vet reached for her wrist, but Rebecca gave him the slip and disappeared into the forest. The vet looked down at the sheep, peeved.

The sheep acted naturally.

The vet acted naturally too, looking at his feet, at his hands, at the sky and back at the sheep. Anywhere but the forest.

Then something strange happened.

Rebecca stepped out from amongst the trees and slowly retreated from the edge of the forest, backwards, her hand stretched out in front of her, as if she were trying to fend something off – a cheeky sheep maybe, or – like so often on their travels – a car or an angry farmer with a chewed stem of leek in his hand.

The shepherdess’s eyes darted from left to right as if there were something there.

As if something were coming.

But nothing came out of the forest.

29A little later their meadow was teeming with humans. They had roared onto the yard in three cars and swarmed out: two through the yard gate to the stables and houses and barns where the humans lived; two out around the yard buildings and chateau wall, where nobody lived; and most of them straight onto the meadow, where the sheep lived.

They went along the fence, searched the hay barn up on the hillside, disappeared into the forest, appeared again, carried Things to the edge of the forest and back from the edge of the forest, spoke to Rebecca, systematically zigzagged across the meadow, muddying the snow and treading the meagre winter grass even flatter than it already was.

The sheep were impressed. They hadn’t expected such a thorough search for Cloud. So, this is what happened when things went ‘too far’ for Rebecca: she called humans with caps for help – and dogs. Two dark sheepdogs with equally dark voices sniffed their way across the meadow.

The sheep shuddered, too frightened and too penned in to panic properly. The eeriest thing about the sheepdogs was that they weren’t the slightest bit interested in the sheep. Not even the strange sheep who once again obviously hadn’t trotted over to the feed trough like the rest of the flock, and was now standing under the old oak enviably free, muttering and scenting the air, seemingly completely disinterested in all the excitement.

The sheep wanted out. They attempted protest bleats to start with – a tried and tested recipe against the evils of the world. If you bleated for long enough, something happened, usually the right thing. But Rebecca, who usually made sure that the right thing happened, just stood there wide-eyed, her arms drooping at her sides.30

The sheep bleated and bleated. Eventually they stopped bleating and fell menacingly silent. But that didn’t get anybody’s attention either.

‘That’s it,’ Maude said after a spell of fruitless silence. ‘Let’s run away!’

That plan appealed to the sheep. Rebecca would soon see how ridiculous a shepherdess looked without any sheep!

‘But how?’ Lane asked.

‘Mopple should play dead again!’ Heather bleated.

Heather liked it when things happened.

‘Why does it always have to be me?’ Mopple muttered, but they had already explained it to him many times before: Mopple was the biggest and fattest sheep in the flock. Unmissable and impressive when he lay on the ground with all four legs in the air.

It had already worked a few times before. The first time was when the apples in the orchard were ripe, and then once again during the hay harvest. Mopple lay lifelessly on the ground, and Rebecca rushed over to them in the meadow, horrified. The shock meant that she didn’t close the gate properly behind her. The third time, Rebecca had grown suspicious and called the vet, especially for Mopple. All the same: playing dead was a tried and tested method of getting on the other side of fences.

Mopple slumped into the snow sighing, then thrashed his legs and died. The other sheep made a bit of space around him so that he could be seen, bleated dramatically and peered over at Rebecca out of the corner of their eyes. But Rebecca was sitting on the steps of the caravan wrapped in a blanket speaking to one of the capmen. Mum appeared behind her and pressed a steaming cup of tea into her hand. It was the first time the sheep had seen her doing anything useful. That showed just how serious the situation was.31

Mopple flailed his legs theatrically. ‘So?’ he groaned from the ground.

‘Nothing,’ said Cordelia.

‘Nothing at all!’ said Ramesses.

‘She can’t hear anything!’ said Sir Ritchfield, shaking his head.

‘She’s not looking,’ said Zora.

‘Maybe we did disappear,’ Cordelia whispered. ‘Before, when the vet came into the pen with us, we all wished we could disappear. Maybe it’s happened!’

‘I didn’t wish I could disappear!’ Heather muttered. ‘I wished the vet would disappear.’

The vet had disappeared, pale and stealthy, straight after Rebecca had stumbled down the hill and anxiously talked to Mum and her talking device.

‘Maybe they’re looking for us,’ said Lane. ‘All of us!’

Bit by bit the strange humans seemed to settle down slightly. They abandoned the meadow and the forest and gathered in front of the shepherd’s caravan. Three men drove away in a car with two dogs. The rest stood around unenthusiastically drinking the tea Mum had brewed in the caravan. One of them threw up. The meadow gate was open.

Now that it had quietened down a little you could hear Tess barking inside the caravan.

The usual humans ventured into the yard as well, curious and ominous as young crows. You barely saw them coming, but every time the sheep peered through the fence towards the yard, a few more had appeared: first, ruddy-faced Madame Fronsac, who always had food in her pockets. She was a potential source of fodder, and the sheep looked at her expectantly. But the rosy-cheeked woman 32didn’t seem to be in the mood for feeding them today. She just stood there as if she’d swallowed something the wrong way, wringing her big red hands. Beside her, Monsieur Fronsac was doing what he always did: watching. Maybe a bit more sadly than usual. Yves appeared through the yard gate, an axe over his shoulder. The sheep wrinkled their noses. Yves was far from being an aromatic delight; he prowled around near the meadow with his axe too much, and he always grinned when he saw Rebecca. Grinned like dogs sometimes do, with their teeth but not their eyes. Rebecca had once told them that he was a ‘dogsbody,’ but even the youngest lamb could see that although he might grin like a dog sometimes, he certainly didn’t have a dog’s body. Not in the slightest.

The goatherder shuffled along the courtyard wall.

The gardener appeared out of the orchard, blonde Hortense and her violet scent wafted out of the chateau. Finally, some of the rarer creatures appeared. Chateau creatures that the sheep otherwise only caught fleeting glimpses of beneath their upturned collars. The woman with the severely scraped back hair who had offered the sheep somewhere to stay. The children. The children were sent away at once.

The rest kept their distance from the capmen and honked away in hushed tones, speaking the unintelligible language of the Europeans. All apart from the goatherder. He just clutched his crook, his hands white despite the cold, white as snow. The sheep were interested in the goatherder – not personally, but for professional reasons, so to speak. With reassuring regularity, he turned up at the goat fence with a sack of fodder, and they had tried to befriend him despite the strong scent of goat. All in vain. Even crazier than his goats, the sheep supposed.

Rebecca was still sitting on the steps of the caravan, leafing 33manically through her big book. The big book transformed the honks of the Europeans into some sort of sense, but it didn’t seem to be doing a particularly good job of it today.

‘Pourquoi?’ squawked Rebecca. ‘Quand? Qui?’

Hortense came through the meadow gate towards her, enveloping the shepherdess in a cloud of ridiculous floral scent, but she didn’t have the answers either. Then Madame Fronsac broke away from the other chateau humans, too, and lumbered up the hill to the shepherd’s caravan. Mum called her ‘the Walrus,’ and only Othello, who knew the ways of the world and the zoo, understood why. The Walrus nervously honked something that Rebecca didn’t understand.

‘She says you should take your sheep and get away from here!’ Hortense explained. ‘In your place, she would leave right away! Tout de suite!’

‘You see! I told you so! That’s what I’ve been saying all along!’ Mum droned from the caravan.

Rebecca fell silent, and Hortense shrugged awkwardly. And then, subtly, something between the humans changed.

They became stiller, but not quieter. The chateau humans backed a little farther away from the meadow fence, almost imperceptibly; Rebecca absent-mindedly tucked a wisp of hair behind her ear; Mum positioned herself on the caravan steps, fluttering her eyelashes. Tess barked even more loudly. All because another car had driven into the yard, bigger and blacker than any of the others.

The Jackdaw got out of the car. The Jackdaw was something like the chateau humans’ lead ram, and he didn’t really look like a jackdaw, not as small or colourful, and obviously he didn’t have a beak. But something about the way he moved, sharp and quick and precise, reminded the sheep of the young jackdaw that 34had been on their meadow a while back. The jackdaw on their meadow had had a drooping wing.

The Jackdaw from the chateau had a limp. Not much of one, and most humans probably hardly noticed it, but the sheep knew, and the Jackdaw himself knew too.

One of the capmen approached him and said something.

The Jackdaw nodded, then he carried on towards the shepherd’s caravan and gently placed his hand on the Walrus’s arm. All of a sudden, the Walrus had tears streaming down her cheeks and was led away by Hortense and Monsieur Fronsac.

The Jackdaw stepped towards the pen and glowered at the sheep. The sheep gazed back uneasily. Up to now they had never taken him particularly seriously because of his limp, which presumably meant he was too slow to be a danger to them, but now they were penned in. The big gaunt face of the Jackdaw hovered over them, so closely that there was no escaping his eyes. Two hands casually nosed their way over the top slat of the fence, blackened by gloves, long and skinny like bird’s claws, even in the gloves. The sheep were afraid one of those nimble hands was going to reach out and grab their wool, a hand that could not be avoided here in the pen.

The hand didn’t come for them, but the Jackdaw’s eyes followed them, a look of cold, piercing interest and something like annoyance – as if the sheep were to blame for something. Every so often his gaze flitted over to Rebecca, and the sheep disliked what happened to his eyes then even more. They became deep and narrow, dark and sparkling, like wells.

‘Attack!’ one of them bleated.

‘Fodder!’ bleated Mopple the Whale, who had got back on his hooves under the beady gaze of the Jackdaw.

Soon all of the sheep were bleating for fodder. Rebecca would 35have to open the gate. Fodder was the right strategy now. Fodder was usually the right strategy.

But Rebecca still wasn’t moving.

‘Well,’ said one of the sheep. ‘We’re in a trap, huh?’ They were in a trap! Mopple and Maude bleated in alarm.

Ritchfield coughed, and Ramesses sat on his haunches in shock.

‘It’s not really a trap,’ Zora said soothingly. ‘It’s just a pen. Rebecca lured us in here. She’ll let us out again. She has to. It’s in the will.’

There were lots of important things in the will. Including that Rebecca had to feed them and read aloud to them. That none of the sheep were to be sold or ‘slaughtered’ – whatever that meant. The vet was in the will too. More’s the pity. The sheep could have done without the vet.

‘That’s not a sheep!’ Sir Ritchfield, the old lead ram, muttered. Nobody paid him any heed.

‘Maybe we ought to hide,’ Cordelia said.

‘Where?’ asked Heather sharply. ‘In the feed trough, maybe?’

‘That’s not a sheep!’ Sir Ritchfield repeated with conviction. The old lead ram was wedged between Lane and Zora, staring into the feed trough. And standing in the feed trough, staring back at him, was a little black goat.

The sheep gave a start. A goat in their midst! And nobody had picked up the scent!

‘Attack!’ the goat bleated, jumping onto Mopple’s broad back. Mopple got the hiccups.

The others were shocked. It was a widely known fact that goats climbed trees. But climbing on sheep as well? It fit the mould, anyway. They tried to ignore the goat. That was easier said than done. The goat hopped from Mopple’s back onto Maude, and 36then onto Lane. She jumped over Ramesses, cautiously arcing over Othello’s black back and finally landed on Sir Ritchfield.

‘Not a sheep …’ Sir Ritchfield bleated. The goat lowered her head and whispered something in his ear.

‘Pigs?’ Sir Ritchfield bellowed anxiously. The goat sniggered.

Heather couldn’t stand it any longer. ‘What do you want?’ she asked the goat. Ritchfield sneezed.

‘Bless you,’ said the goat. ‘The vet.’

She sniffled delicately. ‘I’ve got the sniffles. He’s infected me!’ The goat thumped Ritchfield’s grey back with her front hooves. Ritchfield sneezed for a second time.

The sheep cast all-knowing glances at one another. Completely mad!

‘The vet’s gone,’ said Mopple the Whale in an attempt to get rid of the goat.

‘But he’s coming back!’ the goat said triumphantly. Now, unfortunately, that sounded almost too rational. The sheep fell silent and listened to Mopple’s hiccups.

When the vet came back, they would be long gone. Somehow. Somewhere. Maybe in the shade of the old oak. Or underneath the shepherd’s caravan. Or behind the feed store. Or – ideally – in the feed store. Or at a pinch, in the feed trough. Anywhere. Just not here in the pen.

‘You don’t really want the vet, do you?’ Mopple gurgled after a while.

‘No,’ admitted the goat. ‘I want adventure!’

‘Here?’ Mopple hiccupped agitatedly. ‘On Sir Ritchfield?’

‘Right here,’ the goat confirmed.

Mopple decided to keep his distance from Sir Ritchfield in future. Hiccups were bad enough. You couldn’t graze properly 37with the hiccups. Adventure was all he needed!

‘I want to warn you,’ said the goat. ‘I’m going to warn you!’

‘Too late!’ Ramesses groaned. ‘The vet has been and gone!’ The goat shook her head.

‘Snow?’ Maude asked. ‘More snow?’

‘That too,’ the goat conceded. ‘Listen up!’

The sheep were aghast. Rebecca had forgotten all about them, their meadow was overrun with capmen, and a little black goat was standing on Sir Ritchfield giving a speech. About secrets, danger and adventure. About the moon, which – the goat claimed – was a giant goat’s cheese. And most importantly, about a were-creature. A shapeshifter. A wolf that wasn’t really a wolf. The little goat called him Garou. In short – it was about a whole host of things that the sheep had absolutely no interest in. They tried not to listen as best they could.

‘I think we should work together!’ the goat said in closing. ‘The others think I’m mad,’ she added proudly.

‘Pigs!’ Sir Ritchfield bleated, shaking his head.

‘We think you’re mad too,’ Heather said.

‘Superb,’ said the goat. She hopped off Sir Ritchfield’s back and landed in the far-too-empty feed trough. She started trotting back and forth in it, back and forth, to and fro, to and fro. The sheep gazed at her in fascination. She was so small. Her coat so shiny and black – even blacker than Othello. Her eyes were so yellow and strange, her little horns so sharp. And her scent!

The goat trotted and trotted, muttering things like ‘they don’t believe you,’ ‘not yet,’ ‘what did you expect of sheep?,’ ‘do you think we should?’ and ‘okay, then.’ The sheep felt a bit dizzy from all the toing and froing.

Suddenly the black goat stood still.38

‘Today is your lucky day!’ she announced. ‘You get three wishes!’

‘Concentrated feed,’ Mopple bleated instantly. ‘Hick!’

‘For the humans to leave,’ said Maude.

‘For Rebecca to let us out of the pen!’ Heather bleated.

‘For Cloud to come back!’ Cordelia said – a bit too late. Shortly afterwards the last of the cap-men tipped the remains of their cold tea into the snow and returned to their cars.

‘Revenons à nos moutons!’ somebody said, and Rebecca suddenly looked over towards the sheep. Finally! Then they were fed after all, by a rather preoccupied shepherdess, who tipped in six buckets of fodder instead of the usual five, one of them straight onto the goat.

While they were all stuffing themselves, Rebecca went along the fence with the goatherder and checked the posts.

Then the gate creaked open and the sheep flocked back onto their bruised meadow.

Without Cloud.

The winter lamb hadn’t trotted straight out of the pen like the others. He was still standing beside the little goat at the feed trough. They were about the same size.

‘How did you do that?’ the winter lamb asked.

‘What?’ the goat asked innocently.

‘The thing with the wishes,’ said the winter lamb.

‘A goat spell,’ said the goat.

‘Really?’ asked the winter lamb.

‘No,’ said the goat. ‘Sheep only ever wish for what’s going to happen anyway. Goats, however …’ She looked at the winter lamb with her yellow goat’s eyes. ‘If you want something to happen, then you have to make it happen.’

‘So, what would you wish for?’ the winter lamb asked. 39

‘A lot,’ said the goat. ‘I’d wish for a place where sweetwort always grows, and for the longest goat beard in the world and for a rotten apple to fall on Megara’s head one day. But right now’ – she cocked her head on one side, thinking – ‘right now I’d wish for someone to come and gobble up the moon. The whole thing.’

She looked towards the gate where the shadow of the chateau was proceeding to climb over the fence towards the meadow, as it did every afternoon.

‘I’ve got to go,’ she said. ‘I’m not here if you need me!’

The winter lamb would have liked to ask her a few things – above all her name.

That evening the sheep chewed on their winter grass even more listlessly than usual. Even Mopple. Everything smelled wrong. Too much like dog paws, powder and gumboots. Of human sweat and cigarette smoke. And of something else that the sheep couldn’t make any sense of.

And far too little of Cloud.

‘No sheep may leave the flock!’ bleated Sir Ritchfield in distress.

‘Unless that sheep comes back again!’ said Cordelia.

‘Why doesn’t Cloud come back?’ Heather asked.

‘I wouldn’t come back to a meadow full of dogs and caps either,’ said Miss Maple. ‘She’s probably hiding somewhere. And maybe it’s not that simple to find your way out of a forest like that. Too many trees.’

They decided to bleat into the forest as loudly as they could. Maybe Cloud would come out then!

‘Cloud!’ they bleated in chorus. ‘The vet’s gone! We’re still here! Come back!’

But the forest kept its silence.

3

HEATHER CRAVES SOME WOOLPOWER

‘She’s lovely and woolly!’ said Zora approvingly. ‘For a human,’ said Maude.

The others nodded. The shepherdess was obviously trying to set an example as far as woolliness was concerned. Maybe she was also trying to replace Cloud. She obviously wasn’t woolly enough for that by a long shot.

Rebecca was sitting on the steps of the caravan, wrapped in a blanket, looking unusually large wearing two coats, one over the other, and underneath – the sheep could smell it – the beloved woolly jumper. She had the stalk-eyed contraption hanging round her neck. The stalk-eyed contraption was normally only deployed on bright days when long-legged birds stalked across the meadow, herons or storks with black beaks and once, in the autumn, a couple of cranes in a celebratory mood. Then Rebecca held the stalk-eyed contraption up to her eyes and claimed it made the birds bigger. It was clearly a figment of her imagination; the sheep 41could see perfectly well that the birds hadn’t got bigger in the slightest, but the shepherdess seemed to be enjoying herself at any rate.

But today, with her blanket and the cold and the dusk, it didn’t look like she was enjoying herself at all.

‘I think you’re overreacting!’ Mum droned, passing Rebecca a Thermos from the caravan. ‘Come in! You can’t spend the whole night sitting out there!’

Rebecca took the flask from her.

‘I know. But I’ll sit here for as long as I can. I have to watch over them, at least for a little bit. You should have seen it, Mum! At first, I didn’t even know what it was, if it was a human or an animal …’

‘A deer,’ Mum said. ‘These things happen.’

‘These things don’t just happen!’ said Rebecca, pouring herself some tea. ‘Not like that! It was so messed up, so … Who would do such a thing? A dog? A fox? Hardly!’

Rebecca was shivering. ‘Look how quickly they got here! Four cars, an inspector and dogs, the whole shebang. I mean who does all of that for a deer? It was as if … well, it was as if they’d been expecting it, you know.’

‘Well, there’s nothing else going on around here,’ said Mum. ‘I’m going to shut the door, okay? The cold’s coming in.’

Rebecca nodded and sipped her tea. Then she grabbed the stalk-eyed contraption.

The sheep looked around for long-legged dusk birds, but there were none to be seen. None at all. Not even a chicken. In fact, Rebecca wasn’t even looking at the meadow. Rebecca was looking up at the forest.

‘Hopefully it doesn’t get any bigger!’ said Heather.42

The sheep peered critically over at the trees. The forest was big enough!

‘I think she’s looking for Cloud!’ said Ramesses. ‘She’s looking through the stalk-eyed contraption to make Cloud bigger! And when she’s big enough, we’ll be able to see her over the trees!’

It wouldn’t have been such a bad plan, if the stalk-eyed Thing had worked, that is.

Miss Maple didn’t say a word. She had the feeling that Rebecca wasn’t looking for Cloud. Rebecca was looking for something else – something that mustn’t, under any circumstances, get any bigger.

Rebecca sat on the steps of the shepherd’s caravan drinking tea, making stalk-eyes, getting bluer and bluer with the advancing dusk. The sheep were grazing. The forest whispered mockingly. The chateau was silent. The door leading to the tower opened, and somebody came out, and because he had unusually light hair, the sheep could easily recognise him in the twilight – Eric. Eric didn’t live in the chateau, but he often came by, in an old van, and put goat’s cheese in the tower. Or took it out of the tower. The sheep liked the fact that he never did anything loud. They liked the goat’s cheese less. Now Eric was just standing at the foot of the chateau looking over at the forest with a confused expression on his face. Rebecca waved. Eric waved back. Then he got into his old van and drove off.

After some considerable time, the caravan door opened again. A long strip of golden light fell across the meadow, right over Mopple the Whale. Mopple got the hiccups again. ‘I’ve finished working now!’ said Mum. ‘Come in, darling, or you’ll catch your death!’

Rebecca sighed. ‘Good God, I really hope I find her! A 43runaway sheep is bad enough, but now this! What if …’

‘Sitting around out there isn’t going to help. Come inside! Have a cuppa! If you want, we can read the cards …’

‘Mum!’

‘Well, when he comes tomorrow, just ask the v—’ Rebecca leapt up from the steps knocking over her tea, but she didn’t make it this time.

‘… the vet,’ Mum said. ‘Ask him how best to …’

‘The sheep didn’t hear any more after that. The vet was coming back! With his sharp needle! Tomorrow! Ramesses was the first to lose his nerve, and galloped across the meadow in big panicked leaps. Maude and Lane darted after him, bleating. Soon the whole flock was running up and down the fence bleating their hearts out. They didn’t really believe that running would help stave off the vet, but it felt good.

Miss Maple was the only one who had stayed by the caravan, and she was trying not to think about the vet. Rebecca and Mum were talking about something else. They were talking about it, and not talking about it at the same time.

The tea had melted a black hole in the snow.

Rebecca crossed her arms. ‘Great!’ she said. ‘What do you think it’s going to take to get them back into the pen again tomorrow?’

It would take fodder, thought Maple. Fodder and patience. Nobody could resist fodder. Except …

‘He’s a bit of an oddball,’ said Mum, in an attempt to distract Rebecca from the bleating sheep.

‘The vet?’ Rebecca shrugged. ‘It is a bit strange that he didn’t take a look at it,’ she muttered then. ‘I mean, as a vet … He didn’t even look at it! Not once. As if … as if he wasn’t even 44curious. And he tried to stop me from looking.’

‘He just didn’t want you to see it.’ Mum sighed.

‘He didn’t want anybody to see it. He didn’t want me to call the police. As if something like that could be covered up. I would have found it the next time I checked the fence anyway.’

Rebecca hopped from one leg to the other. Tess leapt out of the caravan and danced around Rebecca. Danced and barked.

‘There!’ Mum pointed at Tess. ‘She ought to keep a look out! I mean, what have you got her for?’

Rebecca stopped hopping.

‘That’s true,’ she said. ‘Tess would bark.’ She frowned, her face blue in the twilight.

‘She didn’t bark!’ she said then. ‘It must have happened yesterday or this morning, and she didn’t bark!’

‘Because it wasn’t on the meadow,’ said Mum.

‘It almost was!’ said Rebecca. She rolled up her blanket and went up the caravan steps.

‘Good night!’ she said to the sheep, who were slowly settling down again. The golden strip of light crept back into the shepherd’s caravan, and the door slammed shut.

The sheep stood in the snow, aghast. Good night! Easy for her to say! She wasn’t going to be lured into the pen and vetted by the vet!

‘I’m just not going to go into the pen!’ Heather suddenly announced.

‘But the feed bucket is in there,’ said Mopple despondently.

‘We just need woolpower!’ said Heather. She’d heard Mum say it. With a bit of woolpower, anything was possible! Some of the sheep fluffed themselves up in an effort to give their wool a bit more power. Others looked sheepishly down at the ground. Cloud 45had been the sheep in the flock with the most woolpower – and the vet had chased her into the forest.

‘We don’t just need woolpower!’ Maple said suddenly. ‘We need a plan!’

‘I’m certain that’s a sheep!’ declared Sir Ritchfield with utter conviction.