8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

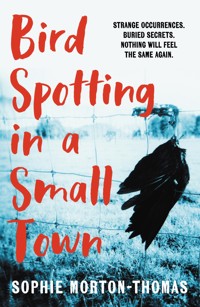

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

My feet are itching to walk to the shore, to leave the kids again, to sit with the birds and pretend none of this has happened.

In a small, isolated town on the North Norfolk coast, Fran's life is unravelling.

As she fills her days cleaning the caravan park she owns, she is preoccupied by worry - about the behaviour of her son, the growing absence of her husband and the strained relationship with her sister. Her one source of solace is slipping out to the beach early in the morning, to watch the birds.

Small-town tension simmers when a new teacher starts at the local school and a Romany community settle in the field adjoining Fran's caravan park. From the distance of his caravan, seventy-year-old Tad quietly watches the townspeople - mainly, Fran's family.

When the schoolteacher and Fran's brother-in-law both go missing on the same night, accusations fly. Yet all Fran can seem to care about is the birds.

An eerie and unsettling novel, Bird Spotting in a Small Town perfectly encapsulates the intensity of rural claustrophobia when you don't know who you can trust.

'A haunting, disquieting novel, exquisitely written. The detail throughout is like acupuncture and the whole thing is difficult to pull away from. I read it in short bursts because each sitting left me with something new to think about' - IAN MOORE, author of Death and Croissants

'The kind of book that gets under your skin, hugely atmospheric and dark in the best possible way' - JENNIE GODFREY, author of The List of Suspicious Things

Perfect for fans of Francine Toon's Pine and hit British crime dramas like Broadchurch and Hollington Drive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 372

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

To Jimbo, Tilly, Felix and Raffy (and Stewart!)

PROLOGUE

They’ll know soon enough.

Everything was taken care of to ensure the best outcome. At first the idea was crazy, ludicrous, not thought out. I couldn’t say it was the most razor-sharp of plans. It happened so quickly. I remember my breath, raggedy, sharp, as if something was trying to burst out of my lungs. I was losing my footing in the fast pace of it all, the almost-running. I couldn’t really run with the weight in my hands. The wind from the sea was whipping at my face in a fury, telling me to slow down. But I couldn’t. I had to listen to the other sounds; the calls of the gulls, saying it was the only way.

You’ve always got to listen to the birds.

FRAN

3 January

The black-throated diver takes its chances; the crash and the slam of colour into the waves catches my eye once again, and I am diverted from my thoughts. He surfaces after a few seconds, prize in beak, turning, a flash of silver, worth embracing the ice-cold of the waves for. I recoil into the warmth of my fisherman’s all-weather jacket, sleeves rolled due to the length. Dom won’t mind that I’ve borrowed it.

Most of the caravans are empty, save for the bloke who stays now and then to escape his wife and kids. I lock the caravan door behind me, head along the narrow path to the next one. The guests are few and far between at this time of year, only the most hardened of holidaymakers risking their Christmases on the coast here. Most families stay away until at least April, once the ground has thawed a little. The second caravan I check, number thirty-one, has a door that sticks, and I swear as my fingers sear from the pain of trying the handle with too much enthusiasm. I poke my hooded head around the door. Still clean. Stepping into the caravan, I snoop around the living area, notice the carpet is looking a little threadbare. Rugs, we need to purchase rugs. We keep saying we will, and then we don’t. Another thing to do. I step out of the unit and close the door behind me, wondering if I should go to check on my sister in number eleven. She’s been here six months, now I think of it. It’s late afternoon; the sun set a long time ago, leaving only a pinky-red swirl of a ghost in the sky, something that used to be.

*

Dom and Bruno are sitting in front of the television, feet up, shoes on. There are still swathes of tinsel in the highest corners of the room that we have not yet taken down. Christmas came and went in a tangle of doubt. I don’t mind that the festivities are over. The occasion is stifling, too much pressure. I like this bit, just after New Year, the bit that many folks seem to wish away. I think of mentioning the bird to Dom but decide not to. We don’t see them often around here, and the sighting was a rarity for me. I think about why we moved here, and why we purchased the caravan park when we had barely even talked about the notion before. I know why I wanted to move here. The birds. Of course, the birds. I don’t think I’ve said this to my husband properly before. My ten-year-old shows more interest in my ornithology obsession than Dom does, though this might just be his age. He does tend to follow in whatever his dad thinks, usually, so perhaps it won’t be long until his interest dwindles. I walk through to the kitchen, gather up the dirty plates on the side, and my mind slips to Ros again.

Later, we walk to the beach. We follow the trail that leads from the house, past the caravan site and down along the side of the church. The last wisps of pink are long gone from the sky, our journey lit by the streetlamps on the one main road which runs alongside the coast. Dom holds my hand on one side, Bruno on the other. I can feel a rush of warmth inside me, not felt for a while. Bruno is jigging up and down from the cold, or it could be the excitement of a late evening stroll. He is chattering away about his return to school, his keenness making me smile down into the scarf which is double-rolled around my neck. I glance at Dom to see if he is enjoying the moment, but his eyes are further up the road, not looking at either of us, red brows knitted. Sooner or later, I know Bruno will mention Sadie, ask the questions, but he doesn’t. I am holding my breath, but he doesn’t.

The lights beam from our left-hand side, my child straining to drag me onto the sand.

*

Ellis has been back a few weeks now. I feel for him. I like his obvious interest-bordering-on-obsession for his daughter. I find myself pacing around the door of their caravan in the cold morning mist, debating whether to knock. It’s still early. I hear the pigeons in the nearby tree, wonder why we get just as many of these as gulls here. I need to see if Ros is alright. There’s no movement in the van even several moments after I’ve hammered at the door with my fist. Eventually, there is a face poking at me through the yellowed net curtain of the window where the second bedroom is. Sadie. I grin, and she smiles back, slowly at first, sleep still covering her at the edges. The door of the van rattles, and she is standing there, all of her eleven years.

‘Mum’s not up yet,’ she states. I smile again, but she seems to be intent on beginning to close the door.

‘Wait, Sadie,’ I say, my hand holding the door still. ‘Is your dad around?’

She thinks for a moment, looks upwards, shakes her head. ‘He went out last night. Don’t know if he’s back.’

‘Can you check?’

She leaves the doorway, heads towards the bedrooms. I hear a door open and close. She is back in front of me, shaking her head again, narrowing her eyes slightly.

‘OK,’ I say. The doubt is like an itch. ‘No worries. Just tell your mum I popped by.’

As I turn to leave, I hear Ros’s slight voice in my ear. ‘Fran.’

She is pale, and I am almost afraid to look her way. Dark bags surround her slitty eyes. A rush of concern heats up my veins.

‘You knocked?’

I make myself look at her. ‘I was checking you were OK. That’s all.’

She squints at me slightly. ‘I’m fine. You know that.’ Her face breaks into a smile, cautious at first.

‘Yep.’ I don’t know what else to say. I just need to know that she is alright. ‘Ellis around?’

Her shoulders hunch up, a casual shrug. ‘No. He’s out.’

‘Dad’ll be back soon.’ Sadie is still in the doorway. She thinks she is a part of the conversation between me and her mother.

‘Late night somewhere?’ I try, looking at my sister.

Ros straightens herself up, pushes hair from her eyes. She might have had two hours of sleep. ‘Look, Fran, I know you mean well, but you did say you were going to stop worrying.’ She pauses. ‘He’s not a bad guy, you know. And we’re very grateful, what with you letting us stay here.’

I am nodding. I’m not looking for appreciation. I know he’s not a bad guy. He’s one of the good ones.

‘I’ll leave you be.’ Ros closes the door without a proper goodbye, and I wonder if she will be able to get any more sleep this morning. Mum and Dad would have been so sad to see her like this. I try not to consider it further. Sadie’s face appears again at the window, not smiling. She pulls the netting across.

I walk back towards our cottage, the sun pushing its way through the clouds, light on dark.

*

Dom is on his way to work, first day back, rushing through the door, mock-surprise on his face when he sees me on our path. He pauses, and I stop walking too. I wonder whether I should plant a kiss on his cheek, but I don’t, and continue my walk to the door.

‘Bye, Fran,’ he says from behind me.

‘Yeah, bye,’ I say. Again, I think of leaning in for a hug of some sort. Instead, I bend down, untie my shoelaces.

He is close to me, still. I can feel the warmth from his body. ‘Bruno doesn’t start back at school today, does he?’

I look up from my crouched position on the floor.

‘It’s tomorrow, isn’t it?’ he says, before I get a chance to speak. ‘He’s so excited.’

‘Yup,’ I agree.

Once I am inside the cottage, I check Bruno is alright in the living room and begin the rounds of laundry from my sister’s caravan and the man in number thirty-one. It’s a thankless task, makes my arms ache, hanging it all out to dry in our spare room. I prefer to fold the dry stuff. Downstairs, I can hear Bruno’s game, cars revving. Dom is right, he cannot wait to be back at school. I know why. The children have a new teacher, and besides, Sadie has promised since before Christmas that she will sit next to him in class from now on. I don’t think he has a crush on her, that would be a little strange considering their connection. I let myself collapse on the sofa, try to get my breath back. I’m not fit like I used to be. And certainly nothing like Ros, with her sunrise runs. At the same moment, Bruno stands, wanders into the hallway. I pull myself back off the chair and tiptoe behind him, hoping my knees don’t click like they usually do. I know he can’t hear me. He’s staring out of the little window beside the front door. It’s like he’s waiting for her. Watching, and waiting.

TAD

They say I’m the most trusting of all of us. I don’t know why, seeing as I’m the oldest. Usually, the oldest from our type of family takes the least shit, has seen and known too much to be bothered with hassle. I’m not sure how much of that applies to me. I have one daughter, and a wife buried in the ground over at the Common. Wasn’t going to have a council funeral, nope. We did it ourselves. There was grieving for a long time.

My family are my friends, yes, but I tend to make friends with the rest of the world too. If my brother is going to find a bird or two and cook them, he’ll offer some to us, or I’m happy to just go and buy one at the local shop. We do use the shops, we have bank cards, bank accounts.

We were up at the Common for almost a year, now we’re moving on. You might think we were sent packing because of mess, or noise, or dogs. We’ve a couple of collies, and a mongrel. Used to have the two horses, the cobs. But it isn’t because of any of that. We’re in a bit of a rush, see. Plus, there are new job opportunities by the coast; at least one of the younger lot already has a job secured. I would have been happy to stay, but I went along with what most of the others wanted.

So, we’re on the move again, from our temporary stop, this family of ours. The land is owned by the great God in the sky, and by nobody else. Grass, soil, wind and rain, it’s all the same. Well, that’s what my folks used to say. Me, I’m just happy to get somewhere to park myself for a few nights, somewhere to lay my head. Anything more than that is just a bonus.

FRAN

5 January

The school is a dark-stoned Victorian building, standing proud, stark against the morning light. Under the grime of the build-up of sea scum on its walls glints a hint of better days. The wind from the sea bears down on us, making us bow our heads, eyes to the ground.

Bruno, young for his age, is hopping around on the balls of his feet, not letting the bitter wind destroy his mood. He stops biting down on his chapped lips to cry, ‘She’s here! She’s here!’

I glance up and nod at my sister, gloves being pulled on, a quick check of her watch. She manages a smile that does not meet her eyes. Sadie is looking beyond me, oblivious to Bruno’s excitement.

‘Say hi, Sadie,’ says my sister.

Sadie looks up at me, blinks. ‘Hi.’

Ros laughs, nudges her daughter. ‘I did mean say hi to Bruno.’

Bruno rushes over to her side, and her face breaks into a smile for the first time. Sadie’s a real beauty when she’s happy.

‘Everything alright?’ My sister’s words brush against the side of me.

I glance up, hands stuffed deep into my pockets. The evening walk to the beach flashes into my mind. The lights at the side of the road, their need to not be obvious, my husband’s slight interest in whatever my topic of conversation was. Just before Christmas, we had been close. ‘Yup.’

Ros is moving closer to me, eyes not so tired now. ‘You know, everything is good. He’s fine. He seems like a different person now.’

I know I am blinking lots, batting away her words. She is talking about her own partner, not mine. Ros is a tower next to me, tall yet wavering. She’s always reminded me of a reed, yielding to the force of the wind. I’ve always been the stronger one. I’ve had to be, I’m the eldest. Ros, she’s softer. Kinder. Our dad used to describe her as being like butter : easy to cut into. I’m still not really looking at her, the wind whisking around my uncovered ears, heat burning. ‘Well, we just want you to be happy.’

It seems like she is smiling genuinely now. ‘I know. Thank you. And we are absolutely fine. I’ll get some work in the next few weeks. I’ll give you some money, obviously. You’re not my cash cow.’

We watch in unison as the teachers come out of the building to greet their students back. An unknown woman, red hair with substantial grey at the roots, scraped back into a bun, stands at the front of Bruno and Sadie’s line. She must be early forties, with spindly pencil legs in high black platform heels, matching black tights. I can see two large and overpowering rings on her fingers but glance away as I realise I am staring. Bruno turns to me, his eyes alight, as he mouths, This is our new teacher.Ros risks a look at me and raises an eyebrow. I think the children had all been expecting a young lady, straight from university. It doesn’t bother me. I like the fierceness of her face, the drawn expression, like she won’t take crap from anyone, although perhaps she is just scowling at the strength of the perishing wind. I find myself looking towards my niece, trying to take in what she may be thinking.

‘Bit of a punky old battleaxe, no?’ Ros says into my ear. The wind is whipping around us so dramatically that I pretend not to hear her words. I try not to laugh at them either.

‘If she takes a dislike to Sadie, I think Ellis will be having words.’

I notice the teacher is now smiling at the class, but there’s something else there; fear, nerves, who knows. I feel sorry for the poor woman, thirty pairs of eyes gunning her down in the first few minutes of her appearance. And that’s not even the kids. I try not to think of Ellis, quick off the mark, straight through the school gates in an attempt to defend his child. The thought makes me shiver a little, in perhaps an almost delightful way. It’s my liking of his protectiveness towards her. Sadie’ll be at secondary school in a few months’ time, she’ll need to be let go of by then. My own child will never seem ready for such a leap.

*

Later, at school pick-up, it is Ellis who appears. I thought he would be at work, but perhaps that particular job ran dry. I don’t ask. He nods at me, almost a smile. ‘You were asking after me the other day?’

I had forgotten the sound of his gruff voice. Gravel throat, that’s how Dom had described him when they first encountered each other. Sometimes I struggle to even make out what he is saying. It’s not an unpleasant voice, just so deep.

Finding myself faltering, I nod, frantically trying to articulate the words I need to say. ‘I was checking that all was well. With the three of you.’

I wish I hadn’t got to the school so early. It’s only 3.06 pm. School doesn’t break until 3.15 pm, and even then, the kids have to be standing behind their chairs in perfect silence before they are allowed out. Bruno is often the last, due to his inability to commit to being deathly quiet.

‘Well, we are just fine. And thanks for paying for my programme. You know I’m grateful; we’ll pay you back.’ He looks sheepish, blinks with his long, dark lashes. My sister used to joke that it always looked as though he was wearing eye makeup. I think again about what a decent man he is, try not to compare him to my husband. My husband whom I want to be with, the man who has stood by me since our early twenties.

I hope my smile looks genuine.

‘Ros and me, we just need time alone, with Sadie. You know, as a family.’

It’s almost a word-for-word repeat of what my sister had said to me.

He chats to me about his daughter, how bright she has been over the Christmas period, how she has been missing Bruno. I don’t mention that Dom and I are beginning to think it would be a good idea for the two children to take a break from each other. I think it will be a joint decision between the two of us. Perhaps Dom is pushing this idea a little more than I would like. Sometimes I imagine their little family will appear at our door like they did back in October, November, probably sick of the four walls of their caravan and desperate to enjoy the heat and space of our cottage. Dom was never that bothered, answering the door with a gruff ‘hi’, leaving the door open for me to speak to them. I suppose he’s become friendlier with them of late. He is trying, I know that. Back then, I wanted to invite them in, offer food, and they would have never said no. It’s at times like these I wish that Mum and Dad were still around. No time for moping. It’s been six years since they passed away, three months apart.

Sadie comes running out and bundles her father; he spins dramatically and is pulling on her plaits.

‘Take the plaits out now, Dad!’ she squeals, pulling at the elastic bands at the end. The ribbons her mum must have tied are now flapping on the ground of the playground, abandoned. ‘I’m too old for plaits!’ I wonder why she has only decided this now, and not earlier in the day.

I can’t see Bruno, but watch the other kids file out one by one. He is towards the back, shoes dragging, bag dragging. He catches my eye and smiles. It’s not a big smile.

TAD

It’s always best to start moving before the sun is up. Miss most of the traffic that way, although it does make the day feel particularly long. It’s winter, so that means starting later than we would have to in the summer months. The others seem to mind more than I do. I’ve been doing it most of my life, moving. Some of the youngsters, they’ve got more used to staying put for a few months each time. Some of them would like to be properly settled. They like the security, they like the schools. They make other friends at the school gates, other women. Some of them talk about getting houses, staying put. It’s up to them; I wouldn’t hold a grudge. But within our family, there is a normality, a sense of being settled, as if we aren’t people who move around. We are just the same as you.

I like the feeling of adventure, seeing where we end up. I think I’m the only one. Perhaps I am nostalgic about it; following a tip-off from another family, seeing it through. I know my sisters, my cousins, some of them want to be more like the communities of the towns and cities around us. Their arms stretch out further than they used to. They will allow everyone in. It’s not a bad thing.

You may be wondering why we’re on the move this time. The main thing is, see, someone got himself into a little bit of trouble at the last place. Not just any old trouble; this was big stuff. My brother, Charlie, he did something. We were so disappointed. It made us look cheap, like people who don’t care. But we do. Part of me wanted to leave him behind, to drum home to him that this is not how we function. But I couldn’t. Not Charlie.

They won’t find us where we’re settling this time. Other side of the country, for a start. We’ve not settled on a proper coast before. The sea will be nice. Great for the kids. Some of the birds are beautiful down there, I’ve heard – not that I’d be one to snatch them, mind. I just like to watch them, marvel at their ripe colours and their movements. I love to watch their sharp little head turns, as if they think someone always has their eye on them. Some people are more into the valuable birds, the rarer ones. Charlie is more into the stuff that I mean, Charlie is into all birds. He especially loves the ones that hunt, hover over their prey, that kind of thing.

FRAN

11 January

I am early to the beach this morning, hood up, the threat of the gulls imminent as they begin to circle above my head. Their screeching unbearable, they eye me as I interrupt their hunting time, although every hour of the day is hunting time for them. They are mostly herring gulls, but I think I can see a great black-backed gull somewhere among the masses. They don’t usually hunt alone, or with other breeds of gull, so today is different. My fingers are already red raw under my puny Christmas-present gloves, I can feel it, but it doesn’t prevent me wandering closer to the part of the beach that is met by the open fields that seem to be owned by nobody. I’m preparing to locate any of the breeds I have been spending the past few weeks searching for, my Polaroid camera, my binoculars, ready. There’s one in particular that I’d like to see. I’ve heard it’s already been spotted in Sheringham, just a couple of miles away.

The sun is barely up, just a muted glow of promise. I can’t see the cottage from where I am crouching, nor even the side of the old church, whose yard of concrete crosses and tombstones dominates the hilly area that slopes down towards the beach. I wonder if the macabre view from one side of the caravan park ever puts off our guests, but I’m yet to hear anyone complain. My sight is drawn to movement in the rushes that separate the fields from the dunes of the beach. I can’t make it out at first but let myself exhale when I realise it is merely our cat, Fergus. He doesn’t usually make his way down here to the sand; the wind plays with his long hair, blows it the wrong way. He’s hunting; a mouse, I think, perhaps a crab. A stab of emotion for our elderly cat is soon replaced with frustration that he is succeeding in scaring away the beloved birds of mine. I place the binoculars that my husband lovingly mocks to my eyes, surveying the land around, looking for movement. I am the only person here. You would think there are a hundred eyes on me. A quick glance around tells me there is nobody watching; still, my gut is telling me otherwise. Silhouettes of darkened faces at the windows of the caravans stare at me with disdain, yet when I turn my head towards the park, I see only the glinting glass panes, no faces. Light glows from the reluctant sun, fractured into a thousand pieces.

The gulls are no longer circling above, but there’s enough of a heavy feeling within me which insists I put down my binoculars, shove my camera into my rucksack and head back across the beach. It’s started spitting with rain anyway. Maybe today is not the day to find the little tern.

*

‘And so she said to Ms McConnell that she wished it was still Christmas because she hates being back at school!’ Bruno is tripping on his own words, can’t get them out quickly enough. ‘She says she misses our old teacher!’

I raise my eyebrow at Dom, who is concentrating on his own dinner, but catches my eye, smiles.

‘Then Ms McConnell said, “If you don’t want to be in my class, it can be arranged that you are moved to another!”’ He is laughing, but there is shock stretched over his small eager face, eyes blinking fast as he waits for my response.

‘I can’t believe Sadie would be so rude so quickly to the new teacher.’ It is Dom speaking. I can see the food going around in his mouth. I know Bruno was expecting slightly more of a reaction, but I don’t want to add more. She’s just a little girl, an unsettled child, my niece. My feet are crossed tightly under the table. I uncross them, try to relax. For some reason, I can’t. Sometimes I wish Dom could be a little warmer with how he words things, how he speaks to Bruno.

‘She can’t keep going around talking to staff like that,’ he says, looking at Bruno. He ruffles his hair. I often wonder if Bruno will follow Sadie’s lead. Sure, he traipses after her like a lapdog at times, but it’s good for him to have a close friend. There don’t seem to be any other friends.

‘Do you think she’s gonna get it when she gets home?’

I shake my head. ‘I doubt it. If anything, her dad will be straight up the school. You know how protective he is.’ We will have to wait until tomorrow to hear if Ros or Ellis have complained. I could call her, ask how today went. But I know what she’ll say. Everything’s fine. But I worry. I don’t want them to get a reputation at the school as being whingers. Perhaps Sadie is being hard work in class. Sometimes it feels like she’s hiding something, something that her parents don’t see. That could just be me. It’s often just the way she looks at me with such… knowing. Or something similar to that. Like she can see right through me.

‘She never gets told off,’ says Bruno, sadly. ‘And I get shouted at for nothing.’

I roll my eyes, hoping it looks comical, reach over to pat his leg. ‘You’re a good boy. And we don’t shout at you!’

Dom is nodding, bringing his knife and fork together. He has wolfed down the meal. He is looking around for something else.

*

At the school the next morning, both Ros and Ellis are there, having just waved Sadie off into her line. Bruno is already there, at the very front. I can feel the pair of them trudging towards me.

Ellis is first to speak, clearing the gravel from his throat before he opens his mouth. ‘New teacher seems to be a complete dragon, then. Already got it in for Sadie.’ He stops, eyes not on me. ‘She sounded so decent, on the first couple of days back; Sadie took a liking to her.’

I swallow down, not sure what to say. ‘Ah, I think you just need to give her a bit more of a chance, perhaps. She’ll be back in Sadie’s good books in no time.’

My sister is there at my hip, not saying anything, but I can feel the weight of her looking at me. I want to hug her, to turn and ask if I can do anything, but my mouth feels so dry, full of cardboard, sawdust.

They are standing in the way I need to walk; Ellis has his hands on his hips. The position looks so out of place on him, in his tracksuit. Sometimes he will dress up in his special tweed jacket for a complaint to the school. It doesn’t suit him. He looks like the second-home owners over in Wells-next-the-Sea, with their red trousers, their slip-on loafers. ‘So we’re having a word tonight, with the teacher,’ says Ellis.

‘That’s good,’ I pipe up. I watch the teacher come out to greet her class, glasses pushed up on top of her head. She’s wearing a coat today, a sheepskin. Her hair is more of a dyed pink now. A pink pineapple. The grey has gone. I see the other parents take in the new shade of hair at the same time as her stripy tights. I like them, personally. Pink, white and green stripes. Reminds me of my old Strawberry Shortcake doll. And my days in Brighton, for a split second. You don’t usually see such individuality here, in our little coastal village in Norfolk. Everyone is too scared to be different. We are just cardboard cutouts of each other, stiffened, starched, two-dimensional.

I am walking now, curling up my toes in my boots that don’t quite fit, trying to hold on to them as I attempt to speed-walk.

‘You in a great rush?’ asks Ros. She is panting to keep up.

‘Kind of,’ I say.

She catches up with me. ‘Listen, Fran, I know you worry about me and money and everything, but…’ She is pausing, catching her breath. ‘We are just fine.’ She gives a little laugh, and I find myself laughing too. I want to rest my head on her shoulder for a second, but brush the idea away, fearing rejection for some reason.

Ellis is further behind, and my sister ceases to chase me, waits for him. He is saying things, calling things out to her, yet the words are tossed and carried away by the squalling wind, useless.

TAD

The wheels can get stuck in the mud occasionally in these winters, or frozen in, but it doesn’t happen a lot. A few shoves and we’ll be there. They’re hardly the huge wooden wagon wheels that you used to see in the States, back in the day. Our trailers are glorified campervans for a start, and not the traditional ones from the sixties either – those ones with big white flowers plastered to the outsides. Ours are larger, more homely, have proper rooms, proper front doors and windows. The kids stay inside, peering out.

You might expect us to lead a very traditional way of life here, and that there are great divides between the men and the women. It’s not true. Every one of us pitches in and does our fair share, it depends on the person. Some of us are lazier than others, but we try to encourage the children to help. It’s good to see them learning tricks so young. I don’t know if kids in brick-and-mortar houses do enough, by the sounds of things. Some of the couples here were married at sixteen, eighteen. That happens a fair bit for us lot, but then some of us don’t marry at all. It doesn’t matter. There is no expectation. You don’t have to be wed to be of value.

It gets lonely for me sometimes, knowing some of the other men have wives and I’m alone, but to be fair, I’m never really alone. There are so many of us I have almost lost count. And that’s what you need. I can’t imagine living in a proper house all alone, just me and my daughter. Besides, Jade needs different company, not just her old dad. We had her when we thought we could never have kids. The only couple in the group with no children at the time. Still, she was a right surprise when she came along. We didn’t even know anything till my wife was over six months gone. A baby born to a geriatric couple, they said. We only saw a doctor a few times before the birth; they were concerned that my wife was too old, that something would be wrong with the baby. I’m still not sure if they were right.

We should be at our new stopping place long before nightfall. Took too long a rest in the middle, kids were wanting to run about a bit. There was a huge car park that could accommodate all of us. Within the hour, we were moving again, some traffic to slow us down, but that’s nothing.

FRAN

19 January

The sea is calm today, mirroring my mood. I am walking as the water laps rings around my ankles. I know I look a little crazy, no shoes or socks in January. It’s the best way to really wake yourself up, feeling the ice of the sea on your bare skin. Dom often laughs when he sees me doing this, it makes him squirm, his hands pushed down into his jeans pockets. It is mid-morning, Bruno already dropped off at the school. I’m trying to convince myself that I didn’t take him ten minutes earlier than usual, just so I could get to the beach earlier for the birds. That would be ridiculous. My binoculars are in my bag, but I’m not sure if I’ll be using them today. I did invite Dom to come for a walk; he’s not at his office but working from home. He declined the offer. I’m not too surprised. He’s not really a man of the outdoors.

I continue to walk for a while, until I can’t feel my feet, and wander from the water to sit on the sand, towel ready in my bag. Drying my feet, I cast my eye over to the caravan Ros and Ellis are staying in. I don’t mind that they don’t pay, not really. I can see the side of the caravan, watch the door, ready to observe whether Ellis is heading off to a job or not. It was strange that he was there for pick-up at the school yesterday. I decide, once I have fumbled about putting my socks and trainers back on, to head towards the caravan park. I just need to know that Ros is OK. And Sadie.

It’s uphill towards the dunes which separate the beach from the field the vans are arranged in, and the gradient almost always catches me by surprise. I am quite out of breath by the time I reach the beach entrance to the park; I hold on to the fence, half bent over, trying to catch my breath. I’m a little overweight, but if you saw my sister, you would think she never eats. Now that I think of it, Sadie herself looks a little underweight. There’s a stab of concern hitting my insides, pink growing into red. She’s just a little girl.

I open the gate to the caravan park, wander towards number eleven. For some reason, I am a little nervous. My heart is pounding faster than usual, but I’m putting that down to my stint of exercise across the dunes. I barely walk uphill anywhere. As I knock at the door, again, there is no response. I try hammering harder. I can see the man in caravan thirty-one shift his curtain to one side, getting a good look at me. I feel like telling him to return to his wife and kids, that they probably miss him, that his wife won’t know what the hell to tell the children about where their dad is.

There’s still no reply at Ros’s door so I try the handle. It shifts with ease, and the door swings open with more compliance than I am expecting. There is nobody in the living area, and my first thought is what a complete wreck the place is. Food boxes and packaging on the table, not cleared away. I recognise one of the boxes as something I gave Ros weeks ago, now out of date, and there is a small, undeniable lump in my throat. I try calling her name, rather than walking straight into the biggest bedroom, but again, only silence follows my call. I try the smallest bedroom first – Sadie’s. Her bed is empty and unmade, just some scant bedding on top, nothing thick enough to keep a little girl warm in the winter. I pace across the almost non-existent hallway to the other bedroom, also empty, with an unmade double bed. As I wander back to the living and kitchen area, I see a bottle in the bin. I push the flip-top lid inwards. A spirit bottle, glass, upside down on its head. There are beer cans too, crumpled, forced into carrier bags. I gulp down hard, tell myself it doesn’t matter. It’s too late, though, my niece has already been affected.

An eddy of wind catches at the back of my neck, and I turn to find the source of the cool air, eyes searching at the walls. The chill feels like a rodent travelling up my spine; I sense that something is wrong, pulling my scarf a little tighter around my neck. I try to ignore the heavy, pushing feeling in my gut. It doesn’t take me long to find the source of the sharp air: the cardboard taped up to the window frame, covering where half of the glass pane should be. My heart is beginning to speed up as I consider why Ros wouldn’t have informed me of the breakage. Light still streams in through the second pane, causing me to scrunch up my eyes a little in the brightness now I am so close. I run my finger around the length of brown tape that holds the cardboard in place, begin peeling it away, my heart not yet slowing down. As I pull down the temporary cover completely, I see the smashed glass, still spiky, serrated at the edges. I shudder at the thought of my fingers being sliced, find myself wondering why Ros didn’t get the glass cleared away cleanly. I imagine her fighting with Ellis, perhaps a bottle being thrown at the wall when he’d had one too many. I shrug, can’t imagine gentle Ellis losing his shit in this way. He is a drinker, yes, but not a violent one. I think of other reasons for the gaping hole in the glass. Nobody else is staying here at the park, apart from the lonely man, and I know my sister and Sadie acknowledge my rule, that no ball games are allowed on site. Perhaps it was not that something was thrown out, in a fit of rage, the climax of a fight between two people. Perhaps something was thrown in. Thrown from the outside. As I stare harder at the jagged outline of the glass, I can see a slight stain of something dark, burgundy, dried around the edges of the forked glass. It doesn’t take a genius to work out that it is old blood.

I scuttle back to the cottage, lots of odds and ends to be getting on with. I can see my sister walking towards me, Sadie in tow. I realise with shame that all I can think about is going to look for my tern again.

‘Sadie said she just saw you leaving our van. All OK?’

‘I was checking you still had heat.’

‘We do, thanks. You know I would let you know if we didn’t. I’m not too proud to ask.’ She gives the little laugh of hers that I like. It makes her sound so young. I wonder whether to ask her about the smashed window, but balk at the idea. Not yet.

‘No worries.’ If I were Dom, I would be asking when she was planning on getting a job. But I’m not my husband. Sometimes I think I should have become a nurse. Or a teacher, something like that. Something in the caring profession. But now I think of it, the last job I would want is having to lead the way for thirty little open hearts and minds. I can barely lead the way for myself or Bruno. Some days I can’t find the right pair of socks to go with my boots. Sometimes my head feels so… woolly.

I lift my hand to wave, but they are already gone, walking away up the path, deep in conversation with each other. I tell myself to call the window repair company when I get home.

TAD

We already knew the police were sniffing about, like I said. That’s why we moved as soon as we could. Well, they would have been right to be checking us out. Charlie hasn’t half got himself into some scrapes in his lifetime, but killing someone wasn’t meant to be one of them. Until now. He’s saying it was self-protection, but from a woman brandishing a hammer? Nah, they wouldn’t be having that if they had managed to haul him into court. He would have gone down for life. I’m not sure the rest of us believed him either, our sisters especially. They stopped talking to him for a while, kept him away from the kids too. Can’t say I blame them. I kept my distance for a while too. He did his disappearing act, came back after a few weeks. He knew we wouldn’t move without him. He never did talk about what happened. I think she was some kind of one-night stand; he did it when he was inebriated, or something like that. I didn’t really listen to what he had to say.

So, that was the reason we left before light. And the reason I didn’t like us stopping halfway. The others don’t seem to worry like I do. They were letting the kids run about, being loud. I became paranoid, thought it made our brother’s crime seem so obvious. I’m sure I saw people looking over, thinking we were something of a sight. It’s true, one or two of our lot think they are above the law, but we’re not. Really, we’re not.

FRAN

24 January

I don’t know how Ellis’s complaint to the school went. All I do know is that he is there every morning and afternoon to drop off and pick up his daughter, his face becoming more stretched with concern each day, paper pulled across a trestle table, ready for pasting. I want to comfort him, but from what, I’m not sure.