2,73 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Wildside Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

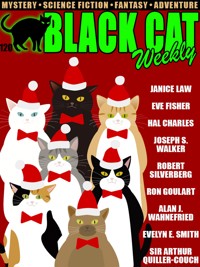

This issue, we have four original tales to entertain you—mysteries by Eve Fisher (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Joseph S. Walker (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman)—and science fiction by Janice Law and Alan J. Wahnefried. Three stories are Christmas-themed, and the holiday comes up in passing in a few other stories as well. Plus we have classics by Robert Silverberg, Ron Goulart, Evelyn E. Smith, ,and Sir Anthony Quiller-Couch, plus a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles. Great fun!

Here’s the complete lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“The Four Directions,” by Eve Fisher [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Christmas Surprise,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“A Right Jolly Old Elf,” by Joseph S. Walker [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“My Christmas Burglary,” by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch [novelet]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Argo,” by Janice Law [short story]

“Garrison Is Dead,” by Alan J. Wahnefried [short story]

“The Yes Men of Venus,” by Ron Goulart [short story]

“Mr. Replogle’s Dream,” by Evelyn E. Smith [short story]

“There Was an Old Woman—,” by Robert Silverberg [short story]

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 188

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

THE CAT’S MEOW

TEAM BLACK CAT

THE FOUR DIRECTIONS, by Eve Fisher

A CHRISTMAS SURPRISE, by Hal Charles

A RIGHT JOLLY OLD ELF, by Joseph S. Walker

MY CHRISTMAS BURGLARY, by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

THE ARGO, by Janice Law

GARRISON IS DEAD, by Alan J. Wahnefried

THE YES MEN OF VENUS, by Ron Goulart

MR. REPLOGLE’S DREAM, by Evelyn E. Smith

THERE WAS AN OLD WOMAN—, by Robert Silverberg

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 2023 by Wildside Press LLC.

Published by Wildside Press, LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

*

“The Four Directions” is copyright © 2023 by Eve Fisher and appears here for the first time.

“A Christmas Surprise” is copyright © 2022 by Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“A Right Jolly Old Elf” is copyright © 2023 by Joseph S. Walker and appears here for the first time.

“My Christmas Burglary,” by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, was originally published in December, 1920.

“The Argo,” is copyright © 2023 by Janice Law and appears here for the first time.

“Garrison Is Dead” is copyright © 2023 by Alan J. Wahnefried and appears here for the first time.

“The Yes Men of Venus,” by Ron Goulart, was originally published in Amazing Stories, July 1963.

“Mr. Replogle’s Dream,” by Evelyn E. Smith, was originally published in Fantastic Universe, December 1956.

“There Was an Old Woman—,” by Robert Silverberg, was originally published in Infinity, November 1958.

THE CAT’S MEOW

Welcome to Black Cat Weekly.

This issue, we have four original tales to entertain you—mysteries by Eve Fisher (thanks to Acquiring Editor Michael Bracken) and Joseph S. Walker (thanks to Acquiring Editor Barb Goffman)—and science fiction by Janice Law and Alan J. Wahnefried. Three stories are Christmas-themed, and the holiday comes up in passing in a few other stories as well. Plus we have classics by Robert Silverberg, Ron Goulart, Evelyn E. Smith, ,and Sir Anthony Quiller-Couch, plus a solve-it-yourself puzzler from Hal Charles. Great fun!

Here’s the complete lineup:

Mysteries / Suspense / Adventure:

“The Four Directions,” by Eve Fisher [Michael Bracken Presents short story]

“A Christmas Surprise,” by Hal Charles [Solve-It-Yourself Mystery]

“A Right Jolly Old Elf,” by Joseph S. Walker [Barb Goffman Presents short story]

“My Christmas Burglary,” by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch [novelet]

Science Fiction & Fantasy:

“The Argo,” by Janice Law [short story]

“Garrison Is Dead,” by Alan J. Wahnefried [short story]

“The Yes Men of Venus,” by Ron Goulart [short story]

“Mr. Replogle’s Dream,” by Evelyn E. Smith [short story]

“There Was an Old Woman—,” by Robert Silverberg [short story]

Until next time, happy reading!

—John Betancourt

Editor, Black Cat Weekly

TEAM BLACK CAT

EDITOR

John Betancourt

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Barb Goffman

Michael Bracken

Paul Di Filippo

Darrell Schweitzer

Cynthia M. Ward

PRODUCTION

Sam Hogan

Enid North

Karl Wurf

THE FOUR DIRECTIONS,by Eve Fisher

My father always drove fast and hard, and that day the speedometer read 110. The speed and the sway, the sun and the heat, combined in a heavy hypnotic sway that left me barely awake. It didn’t calm Mom up front. She rustled maps, wriggled, scratched, and threw out the occasional phrase: “wilderness,” “it wouldn’t kill you,” “never think of anyone else,” and “last gas station.”

“See anything?” Dad asked me. He was jittery.

I looked out the window. “No.”

The land stretched out to the horizon in houseless billows of bleached grass that rippled in the wind like water. I liked it. If the car stopped, and my parents took a nap, I could get out and go down to where the cracked stream bed still held a little water. There was a clutch of cottonwoods at the bend. No one would ever know I was there. I could live off the land. Walk through the tall grass and harvest the heavy seed-heads, chaff them, grind them, mix them into a thin batter to fry on a hot rock until they were golden brown and crisp—

Dad slammed on the brakes, and I almost landed head-first in Mom’s lap. The cop had come out of nowhere.

Dad was very polite, Mom was very charming, and I was very quiet. It didn’t matter. We had to follow the patrol car. While Mom and Dad bickered, I wondered if it was the same policeman who’d followed us for a while that morning, when we left the restaurant. Their voices peaked just as the rolling swells crumbled away into steep cliffs and an oven of heat rose from a dry canyon. The town looked like a toy, and I couldn’t figure out why they’d built it down on that heat, instead of back on the hills where at least they’d have a view. I could see the exact spot I’d choose: a shelf spanning two long fingers of earth. Two rooms would fit there, a bedroom in the back for coolness, and a living room to watch the birds riding the thermals, right at eye level—

“Francie!”

I jumped. Mom and Dad were both looking at me, and it took me a minute to be sure that the glare in their eyes wasn’t specifically about me.

“Francie, we’ve got to go inside for a while. I want you to sit in the car until we come back. Don’t talk to anybody, don’t get out, just stay in the car. Do you understand?” Mom screeched as Dad picked Rikki-tik, my stuffed coyote, off the floor.

He glared at her and thrust Rikki-tik into my hands, “Hang on to him.”

I nodded, keeping my face perfectly still. It was always the safest thing to do.

They got out of the car and gave their bodies that twitch and brush that transformed them into Mr. and Mrs. Watson. Mom stuck her face back in the window and said, “Don’t talk to anybody, don’t open the door, don’t move! You got it?” I nodded.

Then Dad stuck his face in and said, “Keep an eye out, okay?”

I nodded.

I kept an eye out. There was a long sweep of gray sidewalk, then a long sweep of gray steps, and then a square brick building with a white double door. That’s where the patrolman stood. My parents walked smoothly, arm in arm as they went inside.

The street was quiet. The whole town was quiet. I could smell summer through the open window, a mixture of mown grass, baked asphalt, flowers, fertilizer, last night’s charcoal. Across the street was a school with a high chain-link fence around the empty playground. If my parents never came out, that would be where I went to school. I saw myself running across the yard, felt a gust of wind, heard shouting, saw other children swirling in coats and mufflers. Fall. That’s when school happened. But this was summer. What would I do until then?

I could live in the car. The cooler was in the trunk, along with the suitcases and stuff. Beside me in the back seat were my pillow and blanket, a couple of books, and Rikki-tik. Dad’s gun was in the glove compartment, along with a bunch of maps. That was all we owned in the world. When we needed more, there were motels, full of furniture, towels, and little packets of soap. Maybe they’d get me a motel room. Rikki-tik could sit on the bed while I went to school.

We had lived in a house once. I could remember the moss green couch with velvet pillows and velvet trim. I could still feel the softness under my fingers, still feel how the trim just fit between my fingernail and fingertip. There had been a glass lamp, and at night the light danced through it like water. And the closet, where I’d sat on the floor with Rikki-tik. I didn’t miss the closet. But I missed the velvet trim, and the lamp. The lamps in motels were all cold, and they didn’t shimmer. Maybe someday I could get a lamp of my own.

Time was the breeze that came and went.

Time was the sound of a dog barking. We’d had a dog once, too. I could still see Lady, looking at us as we drove away from the parking lot. She can’t live in the car, Dad said. She needs a yard. Someone will take her in, Mom said. She’ll be fine. That had been at that place on the interstate. Now we were off the interstate, heading for where a friend of Dad’s was waiting. There was always somebody waiting somewhere.

Time was my eyes closing all by themselves, my head jerking up, then another wave of sleep. Time was shadows creeping closer and closer. Time was an ocean I could never measure, but it moved, and my parents were back. Mom felt my head and my hands, and made Dad stop at the gas station, where he filled up the tank and she got me a cold pop.

“I hate cops,” Dad said as we pulled away. “What a dump. Who would ever want to live here?”

Mom sniffed. “You’d have to be born here. Even if you married in, you’d never be accepted.”

“Yeah. You’d go nuts. Let’s pull over for a minute.”

“Not until we get out of the county. And don’t speed.”

We passed the county line, and then Dad floored it. The empty pop can went out the window. The clouds on the horizon turned out to be another set of cliffs. The old Buick bucked a little going up them, like a tired horse, the wind rising with us. On top of the cliffs were more grasslands. Miles and miles of them.

“That was way too close back there.”

“That was just a speeding ticket—”

“I’m talking about earlier. What if they knew?”

“You worry too much.”

“Somebody’s got to.”

“So what are we going to do with Francie?”

I clutched Rikki-tik tightly and hummed.

“What do you mean, what are we going to do?”

“We can’t take her with us.”

“We can’t leave her by the side of the road!”

“We’ll find a safe place to leave her for a while.”

“What if something happens?”

“Nothing’s going to happen. She’ll be fine.”

I hummed louder, until my head was full of music that kept perfect time with the swaying grass outside the window.

Dad pulled over at a little rest stop. “Let’s stretch our legs a bit. Give me that thing. We don’t want you losing it out here in the middle of nowhere.”

I handed over Rikki-tik and ran around. There were two weather-beaten picnic tables under two tired cottonwoods. A path led through the tall grass, so I followed it. It led to a stream lined with willows and cottonwoods. A turtle sunned itself on a rock.

“There’s a stream!” I yelled, racing back up. I picked Rikki-tik off the picnic table. “With turtles!”

“Did you get your shoes wet?”

“No, ma’am,” I said, hugging Rikki-tik.

“You’d better not. Here, sit down and have a sandwich.”

The bread was damp from melted ice. I hated wet sandwiches, but I knew better than to say anything. Mom and Dad were like piled tinder, waiting for a spark. Mom kept making sandwiches, as if they were going to eat forever, or more people were coming.

“Listen, uh, Francie,” Dad said, opening Rikki-tik. “Your Mom and I have to go into town for a little while, and we need you to stay here and wait for us. Just for a little while. No problem. You’ll be safe. Anything happens, anybody comes, you just run down to that creek and hide, okay?”

I nodded.

“When you get hungry,” Mom said, jamming the sandwiches into a paper bag, “and there’s pop.”

“Okay. Let’s go. We’ll be back before dark.”

I stood by the picnic table, holding Rikki-tik, watching as they drove away, the way Lady had just stood there, watching us. After a while, I sat down.

Later I got up and went back down to the stream. I set Rikki-tik on a bent willow branch and went over to the turtle. He was still there. A crow cawed up in the tallest cottonwood. Other crows joined it. Along the bank grew rushes and cattails, more grass, irises, and a yellow flower I’d never seen before. I picked some, tied them into a bouquet using a green rush, and stuck them under Rikki-tik’s arm.

All the grass was heavy with seeds, so I started harvesting. I put a handful into my mouth, chewed, and spit them out. I gathered more, though, and piled them on a flat rock. I found a smaller rock and started grinding them. It was hard work. I scraped one of my knuckles raw, and I never did get flour: just a greenish pulp that smelled like cow.

What else could you eat out here? I knew I had the sandwiches, but they wouldn’t last, and I needed to have something else, just in case. I asked Rikki-tik what I should do, but he didn’t know. I lay back in the grass. Above me the heavy seed heads dangled, tickling my face, bugs buzzed around me, Rikki-tik beside me. It was warm and quiet and I went to sleep.

I woke up because of the crows. They were cawing away. It took me a minute to realize the sun was setting, and I wondered, what if my parents were back? I leaped up and ran back to the picnic area. The bag was still there, and the pop, but no car. What if they’d come and gone? No, they wouldn’t have done that. Would they? No. But I knew I’d better not go off again. They said they’d be back before dark.

I ate a sandwich, drank the pop, and waited. I slept that night sitting on the picnic bench, my head on my arms on the table. I was afraid to go off where they couldn’t find me. Sometimes they were gone for a couple of days, and they got mad if I wasn’t where I was supposed to be.

The next day was long. I played with Rikki-tik, ate the rest of the sandwiches, gathered pebbles, picked flowers. Mostly I waited. Only a couple of cars came by. Each time, as soon as I was sure it wasn’t my parents, I ran off with the sandwiches and hid by the creek. None of them stopped. I was still by the creek, weaving a basket out of grass, when the crows came back, cawing and flapping.

I looked up, and three of them sailed down from the tree, heading straight towards me. I blinked. They kept coming at me, cawing and flapping, lower and lower until I jumped up and ran back up the path to the shelter. I heard a rumbling sound as I ran, and I ran faster, hoping it was my parents. It wasn’t.

The road was empty, but overhead dark clouds were chewing up the sky, black against the horizon, and a thin finger of pure light burned to the ground. More light exploded behind the darkness. Something huge and dark flew over, so low I ducked, and the grass across the road bent down, leapt up, and then almost flattened in the gust of wind that followed. The thunder rolled harder than the wind. I’d never seen anything move so fast. Already the sun was gone, and the clouds were racing towards me, ready to sweep me up and away.

I scrambled under the picnic table. A minute later, something burst overhead and there was an explosion of light. I closed my eyes and clutched Rikki-tik tight. The air turned sizzling hot, then ice-cold. The thunder rumbled, the rain and something harder than rain drummed endlessly on the little roof over the picnic table. Everything smelled of wet grass, wet earth, rain.

And then it was over. The sun was back. I got out from under the table, and saw little pellets of ice, the size of my thumb, all around the rest stop. I picked one up and it melted in my hand.

“Are you all right?”

A woman stood a couple of feet away. “Are you all right?” she asked again.

I nodded.

“Good,” she said, coming to the picnic table and sitting down with a grunt. She was very old, with a face like a crumpled paper bag. “Dark That Rides told me you were here. The storm ran fast. Faster than I can. Did you get wet?”

“No,” I said.

“You spent the night here.” It was a comment, not a question.

“Mom and Dad told me to wait. They’ll be back soon.”

She nodded.

“They will!” I said, as if she’d disagreed, but really to convince myself.

“What are you making?”

I looked at the scraps of grass in my hand. “A basket.”

“Hmm. It would make a better hoop.”

“A basketball hoop?”

“No. A Sacred Hoop. Uniting the four directions. East, south, west, north. It brings the four gifts. Healing, hope, unity, forgiveness. Courage at the center. Right here.” She pointed to the middle. “See? You put a strong knot of courage in the heart.”

I shook my head. “I was trying to make it hold together.”

“That’s what courage does, holds things together.” She fingered the little circle of grass. “Here is the west. The storm came from the west. In the west, thunder rides the black horse of power, of endings.”

I don’t know why, but I shivered.

“Also forgiveness. Dark That Rides came from there. East, the red hawk. Vision. Hope. North, the white owl bears wisdom. Unity. South, the sun rises yellow, full of life. It heals all things. The Sacred Hoop. The Four Directions.”

I nodded.

“Can you tell them back to me?”

I remembered the colors. “North, white. East, red. South, yellow. West, black.”

“Good. And the gifts?”

I shook my head.

“North, white owl. Wisdom, unity. East, red hawk. Vision, hope. South, sun. Life, healing. West, black horse. Power, forgiveness.”

We went over it a few times, until I could recite the directions, colors, and animals.

“Why isn’t there an animal for the south?” I asked.

“There is. Tatanka. The buffalo. He lives on the sweet grass.”

“I tried eating the grass,” I said. “It was awful.”

“Then you are not a Tatanka. What are you?”

“I’m a little girl!”

“Yes. But all people have a spirit animal. I am Crow Woman.”

“Some crows chased me back up here, right before the storm. Was that you?”

“Perhaps.”

“Could mine be a coyote? Like Rikki-tik?”

She looked at him gravely. “Mm. Coyote is a trickster. Sacred, but…” She swiveled her hand back and forth. “Shifty.”

I laughed.

She smiled and touched my forehead quickly, lightly. “Red hawk. Now let us tell the Hoop together.” We did, and soon I got it perfectly. Then I yawned. I glanced up at her, afraid she was angry. She shook her head. “Lie down in my shawl.”

“But my parents—”

“I will watch for them. Sleep. All is well. Sleep.”

I closed my eyes and slipped into dreams:

* * * *

Crows on the trees. Lady in the parking lot. The wind in the grass. My parents, walking away. Image after image spilled through my head like water, and behind them, Crow Woman’s voice:

“Dark That Rides. Where are they now?”

A voice like distant thunder: “Riding. Very fast.” The car spraying gravel, the lamp at home, the lightning. “Too fast. Not drunk. Worse. There is much danger.” Thick darkness dropping from the sky. The car almost rolling in billows of grass. My parents’ faces, full of terror.

“Can you keep them safe?”

“If you wish. But if they come back, they will be rid of her again.”

“Has love grown so cold?”

“Some people burn only for themselves.” But here, between these two, was a bonfire, running up the dark in great rivers of flame. “I can make a meeting. What comes of it will come. Coyote may help.”

And then I dreamed I was rising up, high, flying above the endless sea of grass. I flew for a very long time. At one point I flew over a canyon, rock pillars, tangled brush, and a long double row of pines lining one side of it. A young woman with long black hair stood between two of the pines, looking up at me. She laughed and turned to a shape darker than any night behind her. Something blossomed between them. Joy. Then I flew on and on and on…

* * * *

When I awoke, Crow Woman was sitting by a small fire between the picnic benches. It was dark, and the light flickered up her face, making her look for a moment just like the young woman I had seen. Then she was old again.

“No one came,” I said.

“Your parents did not.”

“What time is it?”

“Late. Come, sit by the fire.”

I brought the shawl and sat beside her. She began to speak but stopped, because lights were coming up the road.

“That could be them,” I said, scrunching closer to her.

“Yes.”

The car came to a screeching halt, and my father bounded out.

“Francie!” He stopped, seeing Crow Woman. “Who are you? What are you doing here?”

“Sitting with your daughter,” she replied. “She has been alone a long time.”

“Yeah? Well. It’s none of your business. Come on, Francie. We gotta get going.”

Another car pulled up. Dad turned and swore. It was a highway patrol car, and a patrolman got out.

“Is everything all right, sir?” he asked.

“Yeah,” Dad said, flustered. “Just had to stop so the kid could take a leak. You know how it is, they can’t wait.”

“Yes, sir. Could I see your driver’s license?”

“What—” Dad broke off. “Sure.”

“What’s wrong?” Mom asked from the car. “Is something wrong?”

“Nothing’s wrong,” Dad said. “Stay where you are.”

“Did you build this fire?” the patrolman asked.

“No,” Dad said. “She did.”

“Your daughter?” The patrolman looked at me, then back at Dad. “It’s against the law to start fires out here,” he said. “Haven’t you heard about the drought?”

“I told you, I didn’t start it!” Dad was turning purple.

“Maybe so,” the patrolman said, “but your daughter’s under your supervision. Arson’s a serious offense.”

“It was that woman—”

Everyone looked at the fire, but I was the only one sitting by it.

“Anybody else out here with you?” the patrolman asked me.

“No,” I said, automatically. It was too hard to explain. By now Mom was out of the car. Like Dad, she looked like she hadn’t slept since they left.

“What’s going on out here?” Mom cried. “We’ve got to get moving—”

“I’m going to have to ask you to come with me,” the patrolman said.

“Get back in the car,” Dad said to Mom. He was shaking, but still in control. “Francie—”

“I think the little girl can ride with me,” the patrolman said. “Any objections?”

“No. Of course not.”

We went back to the little town where we’d stopped before, where I’d looked at the playground. I knew Dad was panicked, but the patrolman was very nice. He didn’t ask me any questions, other than if I was all right. I asked him what direction we were going, and he said west. Black, I thought. Endings. He stopped at the courthouse. This time we all went in.

Mom and Dad worked on talking their way out of the mess, whatever it was. I sat quietly in a chair, holding Rikki-tik, and hummed.

“Would you like a pop?” a policewoman asked.

I nodded.

“Come with me and pick out what you’d like.”