Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

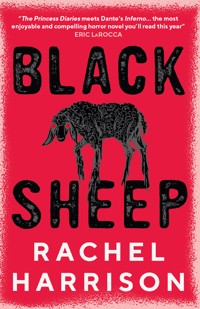

A cynical twenty something must confront her unconventional family's dark secrets in this fiery, irreverent horror novel from the acclaimed author of Cackle and Such Sharp Teeth. Nobody has a "normal" family; but Vesper Wright's is truly... something else. Vesper left home at eighteen and never looked back―mostly because she was told that leaving the staunchly religious community she grew up in meant she couldn't return. But then an envelope arrives on her doorstep. Inside is an invitation to the wedding of Vesper's beloved cousin Rosie. It's to be hosted at the family farm. Have they made an exception to the rule? It wouldn't be the first time Vesper's been given special treatment. Is the invite a sweet gesture? An olive branch? A trap? Doesn't matter. Something inside her insists she go to the wedding. Even if it means returning to the toxic environment she escaped. Even if it means reuniting with her mother; Constance; a former horror film star and forever ice queen. When Vesper's homecoming exhumes a terrifying secret; she's forced to reckon with her family's beliefs and her own crisis of faith in this deliciously sinister novel that explores the way family ties can bind us as we struggle to find our place in the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 393

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Nobody has a “normal” family, but Vesper Wright’s is truly… something else. Vesper left home at eighteen and never looked back—mostly because she was told that leaving the staunchly religious community she grew up in meant she couldn’t return. But then an invitation to the wedding of Vesper’s cousin Rosie arrives. Something inside her insists she go, even if it means returning to the toxic environment she escaped. Even if it means reuniting with her mother, Constance, a former horror film star and forever ice queen.

When Vesper’s homecoming exhumes a terrifying secret, she’s forced to reckon with her family’s beliefs and her own crisis of faith in this fiery, irreverent horror novel from the acclaimed author of Cackle, Such Sharp Teeth and Bad Dolls.

9781803367422 • 23 Jan 2024 • Paperback & E-book£8.99 • 304pp

PUBLICITY

Kabriya Coghlan

These are uncorrected advance proofs bound for review purposes. All cover art, trim sizes, page counts, months of publication and prices should be considered tentative and subject to change without notice. Please check publication information and any quotations against the bound copy of the book. We urge this for the sake of editorial accuracy as well as for your legal protection and ours.

PRAISE FOR BLACK SHEEP

“Rachel Harrison has quickly secured her place as one of my favorite modern horror writers. Black Sheep is a devilish good time made all the more compelling with an exploration of the complexities of family dynamics. Compulsively readable, Harrison’s newest novel is a battle cry for every outcast daughter who has questioned her place among family and weighed the damage of going home again.” Kristi DeMeester, author of Such a Pretty Smile

“No other contemporary author harnesses the humanity found in horror quite like Rachel Harrison. With Black Sheep, she warms your heart, then breaks it, then rips it out.” Clay McLeod Chapman, author of Ghost Eaters

“Once again, Rachel Harrison finds light in the darkness and darkness in the light… BlackSheep sits proudly among her family of contemporary horror classics.” Nat Cassidy, author of Mary: An Awakening of Terror and Nestlings

“Surprising and snappy, Harrison catches you on Hellraiser hooks with a ceremony of grim wit and communal dread. Black Sheep makes a firm case for dodging every family get-together.” Hailey Piper, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of A Light Most Hateful

“Vesper is my favorite new antihero… This is, in short, my ideal read and my favorite Rachel Harrison novel yet.” Anne Heltzel, author of Just Like Mother

“With brilliant underline-worthy writing, thrilling page-turning pace, and genuine laugh-out-loud humor, Black Sheep confirms what I already knew: I will follow Harrison down any dark alley, always.” Claudia Lux, author of Sign Here

“A razor-sharp voice full of wit and humor, along with some edge-of-your-seat moments, will have readers clamoring for more.” Library Journal, starred review

“Harrison finds new ways to press on the bruise of growing up as an outsider, delivering small-town religious horror with wit as sharp as a ritual dagger piercing through a bleeding core of familial trauma. This deserves to be front and center in any bookstore Halloween display.” Publishers Weekly, starred review

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Black Sheep

Print edition ISBN: 9781803367422

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803367439

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: January 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2024 Rachel Harrison. All Rights Reserved.

Rachel Harrison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For the bad kids

1

As I stood singing the birthday song for the fifth time that evening, I realized I was wrong for not believing in hell. Hell was the birthday song. Hell was Shortee’s. Hell was the green polo shirt, the khakis, the whole stupid fucking uniform. Hell was my life.

“And the happy Shortee’s happy birthday to you, hey!” I clapped, and I thought, This must be it. This must be the summit of loathing. I imagined a climber atop Mount Everest, only bitter instead of victorious, grappling with their dissatisfaction with the view.

Kerri presented the chocolate lava cake to the kid, and when he blew out the candle, we all applauded and whooped and I longed to feel what I typically felt, which was numb, instead of what I felt in that moment, which was miserable.

The kid’s parents kissed his forehead, ruffled his hair. His sister asked meekly if she could try a bite. I observed them as I distributed extra spoons and napkins, and for the first time in a long time I thought about my family.

For the first time in a long time I missed them.

Or, if I’m being honest, which I suppose I should be, it was the first time in a long time that I admitted to myself I missed them, and how much. In that moment, I surrendered to the tidal pull of family. Of blood.

My hand found my neck, which was naked, absent the token of my youth, a sometimes coveted but more often resented piece of jewelry.

“You okay?” Kerri asked, ushering me back to the kitchen.

“Sure,” I said, unconvincingly.

“Awesome. Yeah, so, I was wondering . . .” she said, trailing off, distracted by a stain on her polo. “Ugh! Chocolate. That is chocolate sauce, right? Shit.”

“Wondering what?” I asked, checking the window for table eight’s order.

“Do you think you could cover my section ’til close?” she asked, batting her lashes, flakes of mascara falling to her cheeks like ash.

“Why would I do that?” I said, poking my head into the window to see what the line cooks were up to, suspicious they were once again slacking off.

“Because I’m asking very nicely,” she said. “And because you owe me.”

“I owe you?”

“I pick up your shifts all the time.”

I snorted. “When?”

“Last week.”

“I was sick,” I said. It wasn’t a lie. I was sick. Sick of working.

“Please, Ves?”

“Why do you need to leave early?” I said, sidestepping an overambitious busser who was barely balancing a tray of precariously piled dishes.

She picked a waffle fry off of a plate in the window. A plate that was not for table eight. “Sean.”

“Sean?” I asked, dumbfounded. “Really? That guy? You’re ditching work for that guy?”

“You’re so judgmental.”

“The guy treats you like a travel toothbrush. He’ll use you for a week straight, then forget about you for months,” I said. “And you either don’t care or your self-esteem is too low to do anything about it. Either way, the whole thing is messed up.”

Her jaw hung open for a moment, eyes widened like those of a child discovering something new about the world, something brutal. Your burger was a cow. Moo. I knew this look. I’d offended her with my honesty. But the truth was the truth, and she needed to hear it from someone. Might as well have been me.

She crossed her arms over her chest. “Will you take my section or not?”

“I don’t really want to be aiding and abetting, but sure. I’ll do it. But I swear, if I have to sing that goddamn birthday song one more time, it’s game over.”

“Thanks,” she said, turning on her heel. She paused on her way to the back room, looked over her shoulder at me. “You know, you’re not pretty enough to get away with being as mean as you are. And you’re really pretty.”

I almost applauded. It wasn’t easy to burn me, and she’d straight up smoked my ego.

“Order up—got eight in the window,” yelled one of the line cooks. When I went to retrieve it, I thanked him, and then I heard him whisper under his breath, “You’re welcome, Your Highness.”

There were worse nicknames, worse insults. Worse things.

* * *

After ten p.m. Shortee’s turned into a cesspool of drunks and rubes, and some nights I’d have the patience for it and other nights it’d make me want to cartwheel off a cliff.

This night was one of the latter.

“Four top at bar,” Amy, the host, told me while snapping her gum. Staff wasn’t allowed to chew gum, but she did anyway, and I respected her unwavering commitment to such a small act of rebellion.

“Great,” I said, checking the clock. Close was in less than forty-five minutes, and I doubted this new table would be out by then, meaning I’d have to stay late. I cursed Kerri and her bad decisions. I cursed my own.

I peeked over and saw that the party was four dudes, one in a backward baseball cap. If I smiled, feigned effervescence, maybe—maybe—I’d improve my chances of a solid tip. But I doubted it. At that point I’d been at Shortee’s for three years, and in the food service industry for six, ever since I left home at eighteen. I could tell just by looking at someone what they were going to tip, down to the cent. It was like shitty magic, like an evil fairy bestowed a cruel, useless gift on me. A highly specific power of foresight.

“Hey, how we doing tonight?” I asked the guys, approaching the table, struggling to summon any artificial zest. “My name is Vesper and I’ll be taking care of you. Can I start you off with something to drink or do you need a minute?”

“Yeah, uh, I’ll take a . . .” was how each of them ordered.

I kept my head down, scribbling in my book, trying to ignore the hot nudge of a stare. I was being scrutinized in a way that was, unfortunately, quite familiar to me. I knew in my gut what was coming. I considered running.

This is what I get for thinking of them, for missing them, I thought. I’ve called them back in.

“Vesper?”

I looked up, instinctively, at the sound of my own name.

“First of all, that’s a rad name,” the guy said. He was the oldest at the table, about the right age. Mid- to late thirties. Old enough to have snuck into her movies, to have rented the videos. He had a five-o’clock shadow, wore all black. His ears had been gauged once upon a time. A former Hot Topic punk. He’d probably bought her poster, had it up on his wall. I knew the one. In a cemetery she posed provocatively in black fishnets, a chain mail bra, and a signature piece of jewelry that everyone assumed she wore just to be cheeky. “Second, has anyone ever told you that you look exactly like Constance Wright?”

“Who?” I asked. It was how I usually responded, because I knew it’d piss her off.

“The scream queen? You know, the chick from Death Ransom, Bloody Midnight, Farm Possession, The Black Hallows Coven Investigation?”

I shook my head, deriving devious joy from the lie.

“Seriously? You’ve never heard of any of those movies?”

“I’m not into horror,” I said, another lie. “I should get those drinks in.”

“You don’t need to be into horror to know Constance Wright. You have the exact same face. I swear to God.”

He took out his phone, and I bailed. “Be right back with those drinks.”

I’d hoped that by the time I returned to the table they’d have moved on to another topic, but no luck. When I went back to drop off their beers, the guy still had his phone out. He’d Googled her, pulled up her image page.

And there she was. My mother.

“You seriously don’t know who this is?” he asked. “She’s an icon.”

“Dude, relax,” one of the other guys said.

“I don’t see it,” I said, shrugging. “I’m sorry.”

“Really?” he asked. He seemed disappointed, and I felt a twinge of guilt for deceiving him. But it was necessary deceit.

“Maybe it’s the hair,” I said. I’d cut it off in an attempt to avoid situations like the one I was in, but the pixie didn’t make a difference. It didn’t change my face.

The man nodded, retrieved his phone. He stared at the screen, scrolling through picture after picture of my mother.

“Guess you’re a little young. You missed the golden age. Get high, go see the latest slasher. Get scared shitless. Everyone’s talking about horror now, but nothing’s scary anymore. It’s all saying something. Doesn’t need to say anything. Just has to be scary . . .” He was talking to himself at that point. Muttering. “Probably why Constance Wright doesn’t really make movies anymore. You know, she lives down in Jersey. She has a farm out somewhere.”

“Oh wow. Cool,” I said, acting like it was surprising new information. I hadn’t inherited Constance’s acting talents. “Are we ready to order some food, or are we good with the drinks?”

They ordered the spicy Southwest nachos and boneless wings, and any dream I’d had of getting home before one o’clock died tragically right then and there.

I brought them round after round, each guy chugging whatever drink I’d delivered him within minutes, racking up a bill that, in theory, should have led to a decent tip, but they were getting so hammered that I wasn’t exactly optimistic that any of them could do the simple math of calculating 20 percent.

The one guy, the former punk, didn’t bring up Constance again, didn’t bother me, but the one in the backward baseball cap started to annoy me. He’d had the most to drink, and it showed.

“Vessie,” he said when I dropped off the nachos and wings. Only Rosie was allowed to call me that. “Vessie, you make these? You go back in the kitchen and make these for us?”

“Sure,” I said. “Put them in the microwave and everything.”

When I turned to walk away, he reached out for me, swiping my ass with his palm.

I spun around, and he laughed. “Oh, sorry. My bad. Can I get some more of this cheese sauce?”

I nodded and retreated into the kitchen. It wasn’t really Shortee’s policy to give out sides of nacho cheese, but I scooped some into a ramekin and nuked it for a minute, figuring it was easier to shut the guy up than try to explain the arbitrary rules of a chain restaurant.

I checked the clock. It was eleven fifty-four. It also wasn’t Shortee’s policy to kick anyone out. If they arrived before eleven thirty, we had to let them stay, let them finish. Shortee’s prioritizes hospitality, my manager, Rick, would always say. I had this theory that he was a corporate bot masquerading as a real human. I had a lot of theories about Rick.

Just as I thought of him, he popped into the kitchen.

“How we doing, Vesper?”

In restaurant speak “we” is “you,” and if you’re asked a question as a member of the waitstaff, the response had better be positive.

“Good,” I answered through clenched teeth.

“What we doing?”

“A guy asked for more nacho cheese.”

Rick frowned.

“I know, I know,” I said. “But customer first, right? I’m prioritizing hospitality.”

“Just be sure to charge,” he said. “Two dollars.”

“Really? Two dollars?”

He frowned again.

“Got it. Thanks!” I said, taking the cheese out onto the floor, eager to get away from Rick, though not eager to return to the rude, handsy, nacho-hungry bro.

I wove between the tables slowly, inhaled the vague lemony scent of the cleaning solution we used to wipe everything down. It smelled like the end of the night. It smelled like time to go home. But I knew I wasn’t going home anytime soon, and my heart tumbled at the thought of another long, sleepy bus ride in the dark.

I stifled a yawn, stifled the urge to throw the cheese at the wall, rip off my polo Incredible Hulk–style, and set the whole place on fire.

“Here you go,” I said, sliding the ramekin onto the table.

“Let me ask you something,” Backward Hat Guy said, leaning into me, gifting me with a rancid exhale. “We were just talking about how all hot girls have daddy issues. You have daddy issues, Vesper?”

I laughed. It wasn’t polite, or a coping mechanism. It was genuine.

If only he knew.

He must have taken my laughter as a signal of some kind, because he touched me again. This time his hand found my waist, and he pulled me in close. For a moment, I thought of Brody. What it’d felt like to be touched by him. To have his hands on me, hands I wanted, that had permission.

“Hey,” I said, snapping out of my memory and stepping back from the table. “Don’t touch me.”

“Whoa, whoa,” he said. “Relax.”

I laughed again, but underneath this laughter was a staggering rage. It wasn’t fresh; it was there always. A seething I kept stashed away, like a baseball bat behind the headboard. I experienced it in the usual way. A brief flare of blinding, white-hot anguish, followed by a mild chill of despondence, and finally a return to indifference.

“I’ll be back with the check,” I said, turning to leave.

“We’re not done,” he said. “You’ll do what we tell you. We tell you to bend over, you bend over, or no tip.”

I whipped around, stunned by the audacity.

“Who’s your daddy now?” he asked, raising an eyebrow. The rest of the guys snickered, shook their heads, said nothing.

He reached for the cheese, and maybe it was his own clumsiness or the result of an overzealous microwave, but somehow the cheese bubbled up.

It exploded, essentially.

And it exploded all over his face.

He didn’t scream at first, so at first glance it seemed like an innocent spill. But then I noticed the curls of steam slithering from him like skinny pearlescent snakes. And then I heard it. The sizzling.

Then he screamed.

“Ah, ahhh! It’s burning me! It’s burning my fucking face! Ah! Help me!” He fumbled for his napkin. The former punk—a quick thinker—tossed his beer at the bro’s cheese-scalded face, but the beer did nothing to mitigate the damage. The guy kept screaming. He had a napkin now and was wiping away the gobs of orange cheese. In their wake, pocks of skin were sunset red and peeling. And I could smell the injury, the burning flesh. A foreshadowing.

It was bad. It was really bad.

This time when I laughed, it wasn’t because I thought it was funny, or because I was angry. It was nervous laughter. Doomsday laughter.

And it was not appreciated.

* * *

I sat at the bar with Rick. He’d made me the Shortee’s signature honey jalapeño margarita, which came in a fishbowl glass, and I knew then that I was getting fired.

He had a glass of water with a lemon wedge.

Rick was the kind of guy who wore his pants just a little too high, a brown braided belt buckled one hole too tight, his green polo tucked in. I had a feeling he relished the polo. I had a feeling he slept in it. He was a “don’t think of me as the boss” kind of boss. Kerri would talk about how she felt sorry for him, say he meant well. Even though I’d grown up sheltered, I wasn’t naive. I suspected that Rick had a mean streak, or some secret unsavory fetish; maybe he had tortured small animals as a child. Maybe he expected things of the world, and in the absence of what he felt he was owed, he fostered an ugly resentment that would rear its head eventually.

Kerri told me I should try not to think the worst of people.

“I don’t,” I’d told her. “It’s intuition.”

She didn’t seem to believe me.

“So,” Rick said, and cleared his throat.

“So,” I repeated, and sipped my margarita. If I was about to be unemployed, I was going to suck every last drop of tequila out of the gigantic glass in front of me. Take whatever I could from Shortee’s before it left me with nothing.

“This is why we don’t do sides of cheese,” Rick said, shaking his head.

“The guy asked. Should I have said no?” I didn’t raise my voice. I didn’t have the energy to be angry. I rarely did. Constantly treading water really takes it out of you. “You said to charge two dollars.”

“I’m not trying to get into a blame game here, Vesper. But we might have a lawsuit on our hands.”

“Sure,” I said. I licked the salt rim. “I mean, the guy grabbed me multiple times, but sure. Let him sue because he’s too uncoordinated to handle nachos.”

“He grabbed you?”

“Does it matter?”

Rick sighed, which I took as a no.

Of course not.

“Look,” Rick said, “I’m going to have to let you go.”

I waited to feel sadness, or relief, or fear, or shame. But I just felt drunk. I could never handle those big margaritas. I gave a little hiccup and said nothing.

“It’s not just about tonight, Vesper. There have been several complaints.”

“That so?” I asked. “Several?”

“About your attitude,” he said, brow furrowed. “That you’re not a team player.”

“I was covering for Kerri tonight,” I said. “This incident occurred in her section. If I hadn’t so kindly volunteered to take over, I wouldn’t be in this situation.”

“There it is,” he said. “The attitude problem. The sarcasm. Shortee’s is a family. No one’s above anyone else.”

Your Highness, I thought. I wondered if it was the line cooks who complained.

“I’ve been here for three years,” I said, not certain why I felt compelled to fight for a job I didn’t even care about. It wasn’t about the money; I’d find another job, another Shortee’s. It wasn’t about the injustice; I’d known from a young age there was no such thing as fair. I thought maybe it was about getting fired instead of quitting, which I’d fantasized about since my first shift. Or maybe I was just so frustrated with my life, the one I’d sacrificed everything in pursuit of, that I couldn’t stand to have fucking Rick lecture me about my attitude. “It’s fine. If I’m honest, if I had to spend another day feigning enthusiasm about deep-fried mac-and-cheese bites, I probably would have lain down in traffic. And I hate this polo. I hate this polo so much. We all look like preteen dweebs on a class field trip. It’s impossible to get any respect while wearing this shirt. We’d have better luck wearing dunce caps.”

I gulped down the rest of the margarita as fast as I could.

“I’ll mail your last paycheck,” Rick said coldly, clearly offended by my polo comment.

“Cool,” I said, sliding off the barstool. “Thanks so much.”

“Vesper?” Rick called out to me as I was halfway out the door.

I almost kept walking, but I guess maybe I was curious to hear what he had to say.

“Can I give you a piece of advice?” he asked. He didn’t give me an opportunity to answer. “You’re smart. You’re a hard worker. You’re beautiful. You’re young. But you’re not above the rest of us. You’re not special.”

“Is that the advice?” I asked flatly.

“You know what? Never mind. Good luck, Vesper. I wish you all the best.”

I knew he was lying. He wanted me to fail, so he could be right about something. So he could feel better about himself.

I let the door slam behind me and stumbled out into the parking lot, tequila dizzy, guts twisting. The first eighteen years of my life, all anyone had done was dote on me, tell me how special I was. But ever since I’d left home, my family, the church—ever since I’d entered the “real world”—all anyone did was tell me I wasn’t.

I still hadn’t quite figured out who I wanted to be right.

* * *

I wasn’t so drunk that I couldn’t take the bus, but I was drunk enough that I probably shouldn’t have. I just couldn’t bear the cost of an Uber, enough to feed myself for a week, especially now that I was newly unemployed. So I took deep breaths when the motion made me queasy. My stomach lurched at every stop, the driver slamming on the brakes. Vomit loomed in the back of my throat. I held it in until my stop. I toppled off the bus and hovered over a trash can. Spicy margarita’s revenge.

There were no witnesses, thankfully.

I climbed the hill up to my apartment building. It wasn’t far, about a ten-minute walk, but I was work worn after a double shift, my feet blistered, my head pounding; my back, my shoulders, my neck, my joints all squealing. The exhaustion bore down on me, making the hill seem steeper than usual.

The air was like a membrane—viscous, thick with humidity—and the heat hadn’t relented. I soured like milk left out on the counter. My blood curdled in my veins. I felt inhuman, like a collection of chunks. My feet dragged with every step up the impossible incline, and I was tempted to collapse right where I was, plant a white flag, and let gravity win. Lose somewhat gracefully.

The top of my building appeared over the hill. I could see my apartment, the second window down, on the corner—it was pitch-dark inside, with my cheap white curtains billowing out of the open window, reaching into the night like a longing ghost.

Above, the moon shone silver and pretty, almost ripe for the picking, as my father used to say. The glittering sky rested like a crown on the horizon. So many jewels—stars burning, burning, so desperate to be seen, seeking attention over light-years. Easy to forget stars are mortal; they’re born, and they die. They shine for legacy.

It was July, and July is always stingy with breezes, a simmering miser. But this night . . . this night seemed antsy. I didn’t feel a breeze, but I saw it skittering all around me. The trees that neatly lined the street swayed, leaves waving. They caught the orangey light of the streetlamps, which seemed to glow more intensely than usual. Beyond the sidewalk, something rustled the bushes. The flowers, lush and blooming, craned their necks.

The movement, the light . . . these things I maybe could have dismissed. It was the silence that unnerved me, that confirmed the wrongness of the scene.

Yes, I was exhausted, and yes, I was drunk, and yes, I was a bit raw from being unceremoniously sacked. But I had spent years, wittingly and unwittingly, calibrating the alarm inside me that alerted me to danger. Those of us who need it don’t have a choice.

So I knew when I wasn’t alone. I knew when I was being watched.

Maybe everyone experiences it differently, the sensation of hidden eyes. For me, it manifested like repeated prodding with a sharp stick. Like an itch on the inside of my skin.

Around me, the night remained too beautiful. Too clean. No litter on the sidewalk, another disturbing observation. The scene seemed eager for me to trust it, so, of course, I didn’t.

I stood, unsettled, teetering in the middle of the street, searching for evidence, for visual proof of a threat. I waited for the appearance of a figure, a shadow invading the circles of light from the streetlamps or creeping out from behind a parked car. I waited for sound, a noise to disrupt the excessive silence. I waited for an antagonist to emerge from the dark.

The thing about danger is, it always has a face. It chooses whether to show it to you or not.

“Go on—come out,” I whispered. “Why delay the big reveal?”

There’s something you should know about me, that I’ve come to learn, that I should probably tell you now, so the rest of this makes sense. Seems I’m the type to pick at a scab until it bleeds, then peel back the skin to see what’s underneath. The kind of curious that invites self-destruction.

But I’m also impatient, and after what felt like an hour of nothing but peculiar quiet and the incessant pawing of humidity, I relented, turning back to the hill and continuing my climb. I plodded on—pushing through the dizziness, the ache, the pouring sweat, the lingering burn of margarita and vomit in my throat—and finally, finally, made it to the door of my building.

I fumbled with my keys. I peeked over my shoulder one last time, half expecting to see someone standing at the end of the walkway, a lurking stranger. But there was no one. I was alone.

All alone.

I managed to get the door open. I had to climb up three flights of stairs on my hands and feet like an animal. My drunk, trembling legs couldn’t hold me.

When I got up to my apartment, the mystery of my suspicion unfurled so perfectly, like the gentle pull of a ribbon flattening a bow.

There was a large red envelope resting on my doormat.

All this time, they’d known exactly where I was. Of course they had.

So, that’s why the night was acting so strange, I thought. It was scared.

I snatched up the envelope and hurried inside, locking the dead bolt behind me. I shuffled across the floor, kicking off my sneakers, tearing off my polo and tossing it in the trash. I freed myself of my bra and collapsed onto my bed, forever unmade thanks to its position; it was wedged in my small studio apartment’s makeshift sleeping nook, originally intended to be a closet.

I turned the envelope over in my hands. It was silky to the touch, and weighty. I never thought I’d describe an envelope as beautiful, but it was.

I also never thought I’d describe an envelope as eviscerating, but it was. It was the sword shining in the sun on the walk up to the execution block. It was soul wrenching, spine crushing, inducing a panic so profound, I felt as though I were levitating above my mattress, abandoned by the laws of nature, which wanted nothing to do with me and the ticking bomb in my hands.

Once again, I chastised myself for having thought of them earlier that evening. For having missed them.

You called them back, said a hissing voice in my ear that did and didn’t sound like me.

Part of me wanted to frisbee the envelope out the window and move on with my life. Watch some trash reality TV dating show on Netflix that would reassure me I wasn’t such a disaster. Start a job search in the morning, or maybe just start over someplace else, pack my shit and go, a total reset, something I’d often daydreamed about but was too lazy to implement.

But, as I said, I’m curious. And, if I’m honest, I’d been waiting.

I’d been waiting for that envelope ever since I left. Waiting for someone to reach out. Ask me, beg me. Say, Please come home, Vesper. We miss you. Please.

Because maybe I was desperate for an excuse, or maybe I was desperate for an opportunity to say no, to reinforce that I’d made the right choice by leaving six hard, painful years earlier.

The envelope didn’t say whom it was from, for obvious reasons. No return address.

I thought maybe it was from Rosie, more a sister than a cousin, more a soul mate than a best friend.

Or maybe from Aunt Grace, who was more a mother to me than mine had ever been.

Definitely not from my mother, scream queen / queen bitch Constance Wright.

Maybe from Brody, telling me he was ready now. Ready to run away with me.

No, I thought. The envelope was too official to come from Brody. And the way it felt in my clammy grasp, I understood that whatever news was tucked inside, it wasn’t good.

The anticipation mounted, dread’s meaty hands tightening around my neck. So I slipped a finger into the seam and tore the envelope open, tipping the contents onto a tangle of sheets. Out slipped several small pieces of luxe stationery, edges gilded. I picked up the largest and held it up to the light.

Together we invite you to celebrate the marriage of

ROSEMARY LEIGH SMYTHE

&

BRODY GIDEON LEWIS

Saturday August 16th, Five o’clock in the eveningMass & CeremonyWright FarmThe Hamlet of Virgil, New JerseyFormal attire

And at the bottom, scribbled in black Sharpie . . .

Please come home. Stay for the weekend, or forever. We love & miss you.

I let the invitation fall from my hands. I went straight for the emergency pack of cigarettes I kept in a kitchen drawer, among take-out forks and spoons, chopsticks, dull knives. I lit one off the stove top, sat at the kitchen table smoking it, staring out into space, arrested by utter shock. I ashed my cigarette on the table, on the floor, on my lap, wherever.

At some point, I retrieved the invitation, read it over and over as I chain-smoked. My disbelief would return, and I’d need to read it again. I might have gone on reading it forever, turned to dust at the table, had I not been distracted by the blue flame licking up from the stove top.

Either I’d forgotten to turn off the burner or it had reignited itself.

For a moment, I just stared dead eyed into the flame, thinking of home. Thinking of Rosie.

Sometimes Rosie’s hair looked like gold. Other times, it looked like fire.

A memory slipped through the dam I’d spent years building.

On this afternoon, Rosie’s hair was pure fire. The two of us baked under the sun—like a heavy yellow stone directly above us that seemed it might tumble down any second, ending the day or ending us. The grass was prickly at our necks; under our knees, our bare calves. We wore cutoff jean shorts we had made ourselves with a pair of scissors and a dream.

We did this often. Would just lie out in the field gazing up at the sky, talking about whatever. Everything and nothing.

That’s how it was with best friends. With sisters. The highest of stakes, the lowest of stakes.

“My lips are so chapped,” I said. “They’re going to fall off.”

“Here,” she said, digging into her pocket and handing me a birthday-cake-flavored lip balm. Rosie always had things. Gum. Band-Aids. Lotion. Hand sanitizer. Faith.

I never had anything.

“You’re my hero,” I said in a funny ingenue voice.

She giggled. “Need those lips to kiss your boyfriend.”

I rolled my eyes. “I don’t really think of him like that.He’s . . . Idon’t know. He’s just Brody.”

“You’ll get married,” she said. “It’s obvious.”

I wanted to tell her that it wasn’t. That nothing about the future was obvious to me. But I said only, “We’re thirteen.”

She turned over onto her stomach, picked at the grass. “I hope I get to marry someone just as good.”

“Whoever you marry will be very lucky,” I said, tossing back her lip balm.

“Aw, Vessie.”

“The luckiest.”

Go figure. I knew fuck all about luck.

I knew fuck all about anything. I’d thought Rosie and Brody would mourn my absence, not use it as an opportunity to get together. All my years away, they hadn’t been pining after me. No. Apparently, they had each other.

I stood up and turned off the burner, killed the flame.

2

I realized, once again, that I’d been wrong about hell. I’d come around to the fact that it did actually exist, but it wasn’t the birthday song, and it was far away from Shortee’s. I’d found it, for real this time, beneath the bustling, steaming streets of Manhattan.

Hell was Penn Station.

New Jersey Transit, the shadow realm.

I attempted to take refuge in a grimy nook as I waited for my train, but it was impossible to get out of the way. A man slammed his suitcase into my shin, sending me reeling into a nearby trash can. He gave a frustrated grunt, shook his head at me as if it’d been my fault.

“So sorry, sir,” I called after him. “The audacity of me to have mass.”

He ignored me and kept walking.

I observed my fellow Jersey-bound travelers, strangers, people I’d never know, fiddling with the lids of their coffee cups, dropping their receipts on the floor—brazenly littering. They sat on the stairs beneath signs that said not to sit on the stairs. They conversed loudly, scolded their children too harshly or not at all. I watched a child crawl between the legs of an unsuspecting businessman. I watched a young woman with long blond hair and Louis Vuitton luggage park herself directly in front of a large box fan, hogging perhaps the only source of relief in the entire subterranean sweatbox.

I searched for a pair of eyes to meet mine, some hint of reciprocal existential misery. There were eyes, hundreds, maybe thousands of eyes, but they were all glazed over, eerily still, like zombie eyes, glowing pale, reflecting that iPhone fluorescence. That gentle, stealth-damaging brightness.

I didn’t judge them for escaping into their phones; I envied that they could. Mine had died, and I couldn’t find anywhere to plug it in. I figured there had to be an outlet near the box fan, but the blonde was sitting right in front of it, her suitcases surrounding her like a fortress. She sprawled out on the floor, watching videos sans headphones, sound all the way up.

In my head I heard Kerri’s voice telling me not to think the worst of people. Maybe I’d have been inclined to take her advice had she not ditched work to go hook up with a guy who didn’t even like her, which had dominoed into my getting fired. And maybe I’d have been inclined to take her advice had my instincts not been right 100 percent of the time. And maybe—justmaybe—I’d have taken her advice had I not been heading to the wedding of my cousin / best friend and my first and only love. Had I not been returning to the home I left with the intention of never, ever, ever going back. And had I not been, quite honestly, just a little unhinged.

“Excuse me?” I said to the blonde. I could see the outlet just over her shoulder.

She pretended not to hear me.

I considered giving up then, but as I said, I was a little unhinged.

“Sorry, there’s an outlet behind you and I need to charge my phone.” I held up my phone, as if I were presenting evidence in a showy trial.

Again, she ignored me. I watched a vague annoyance pass across her foundation-caked face, her only acknowledgment of my presence.

“I’m really sorry to bother you,” I said, which was true, but I was sorry for me, not to her. “I wouldn’t ask if I didn’t need it.”

She rolled her eyes and clicked her tongue. “Go ahead, then. I’m not in your way.”

But she was very much in my way.

“Fine,” I said, giving up.

Sometimes I would imagine a ledger inside myself, floating in my skull. An ancient-looking scroll where, with quill and ink, I’d tally up the incidents that subsidized my cynicism, my lack of faith in humanity. I had no idea where the visual came from, or what purpose it served. It was goofy. Sometimes it’d make me feel better, other times not so much.

This time, on this particular day, I couldn’t be passively jaded, because I was actively upset. It was one thing to have no faith in humanity, to be disgusted, disappointed by the general population. But I was carrying around this fresh resentment for the person I’d always held up as an exception. As the epitome of good.

I couldn’t get over it, get past the question How could Rosie do this to me?

It overshadowed all other questions, including the question I should have been more concerned with, which was Why was I invited? Or really How was I invited?

I’d left the church, and once you left, you were out; you were done. There was no going back, no coming and going for visits, holidays, anniversaries, birthdays. Weddings. And no one had reached out to me in the six years I’d been gone, so why now? Why this?

I needed to know, and I’d be damned if I let Rosie and Brody get married without having to look me in the eye first.

I’d been stewing in my mess of emotion for weeks, and now that I was at the train station, that I’d purchased my ticket home, that I held it in my hands, all I wanted was to disengage. To fuck around on my phone, get lost in an article about the ethics of cryptocurrency or the legit existence of UFOs or an acrimonious celebrity divorce, or read about fall fashion trends, lament the resurgence of low-rise jeans, or stare at a picture of a disheveled Ben Affleck buying deodorant at a West Hollywood CVS.

But I couldn’t do any of that, and I couldn’t do it because the inconsiderate blonde and her expensive designer luggage were in the way and she refused to move two inches to help a stranger asking politely for a simple favor. She laughed at something—a loud, trilling giggle—and as she did, she let her head fall back, getting dangerously close to the fan.

What if the blades got hungry? What if they ripped her pretty blond hair from her stupid thick head? Would she be laughing then? Would she regret not moving?

I wondered if it was spending my youth reading religious texts that detailed brutal punishments, savage justices, that had conditioned me to violent revenge fantasies, or if I was just fucked-up. It was impossible to know.

I hoisted my bag over my shoulder and headed toward the bathroom. There was a long, long line.

When I finally got to the sink, I splashed some water on my face and wiped up with a paper towel.

I briefly glanced at my reflection. I’d never liked to linger in front of the mirror, since my face was so similar to the face of someone I couldn’t stand, who couldn’t stand me. For as long as I could remember, whenever I looked at myself I saw her. I used to wonder if she experienced a similar phenomenon, but after years of contemplation I’d concluded that Constance Wright was too self-centered to see anyone but herself.

When I emerged from the bathroom, the blonde was gone, the outlet was free to use, and I wondered if I had just been impatient. If I was the asshole stranger. If I was perhaps too eager to condemn mankind over a small inconvenience.

“Now boarding on track twelve . . .”

A human wave crashed through the station, sweeping past me.

“Making station stops in Secaucus . . .”

I didn’t know if the train being called was my train; it was too difficult to determine from the muffled announcement, and I had no direct view of any of the monitors, thanks to the stampede. I had no choice but to surrender to the masses, or else suffer a Mufasa fate.

I was bullied all the way to track twelve. Everyone was too close, the concept of personal space incinerated in the desperate rush to the train. There were shoulders, knees, elbows, fists, all these confusing extremities that didn’t belong to me but seemed attached somehow, tangled, inextricable from me. All these hot mouths, breath scorching the back of my neck. Someone smelled, and I was afraid it was me. I was damp, but unable to determine whether it was my damp or if it was transferred to me. Was it my sweat, or a stranger’s?

I looked around and saw mangled expressions, experienced a palpable foulness. A rottenness. I wondered, Why do we all absolutely lose our shit when traveling? Is there an evil entity that roams around train stations and bus stations and airports, feeding on our rationality, leaving us rude and stupid and impatient and incapable of following simple rules? What other explanation could there be?

There was a bottleneck at the top of a narrow escalator, the only means to get down to the platform. There was also a bottleneck at the bottom of the escalator, on the platform, where the crowd was stagnant, seemingly ignorant of the throng streaming in behind them. They roamed slowly toward the train, stopping to check and double-check the track number, to look around, admire the scenery. There was a woman at the bottom of the escalator who couldn’t step off because the man in front of her blocked the way. She tried to step backward, but there was no doing that either, because there were people behind her, bearing down, propelled by the escalator. She let out an uncanny wail. Its pitch was disturbing.

Fear manifests differently in everyone. It thrives in certain throats.

“Move! Move!” somebody yelled. Then everyone yelled.

It was so zany, so terribly ridiculous, that I started to laugh, only I couldn’t really laugh, because I couldn’t breathe. There was no inhaling; there was nothing to inhale except the neck of the person in front of me, so close, we might as well have been conjoined. And whoever was behind me, the pressure of their body—bones, muscle, skin, heat—was smothering. I was being crushed. It was a human crush.

I thought, I am not dying in Penn Station. After everything, I’m not going out in hell.

And also, I’m showing up to this wedding if it kills me.

“Step out of the way! Move!” I shouted with as much authority as I could muster.

There was a sudden shift. The crowd parted, the bottleneck shattering. I fell forward, tripping over my feet as I stepped off the escalator. I recovered quickly and hurried on, lest I get trampled.