Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

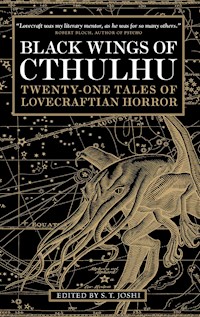

Modern Masters of Terror The works of H. P. Lovecraft have inspired brilliant writers for decades, leading Stephen King to call him the "twentieth century's greatest practitioner of the classic horror tale." S.T. Joshi-the twenty-first century's preeminent expert on all things Lovecraftian-gathers greatest modern acolytes, including Caitlin R. Kiernan, Ramsey Campbell, Michael Shea, Brian Stableford, Nicholas Royle, Darrell Schweitzer and W.H.Pugmire, each of whom serves up a new masterpiece of cosmic terror that delves deep into the human psyche to horrify and disturb.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 704

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO EDITED BY S. T. JOSHI:

Black Wings of Cthulhu, Volume 2 (forthcoming)

Black Wingsof Cthulhu

TWENTY-ONE NEW TALES OF LOVECRAFTIAN HORROR

EDITED BY S. T. JOSHI

TITAN BOOKS

Black Wings of Cthulhu

Print edition ISBN: 9780857687821

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857687838

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: March 2012

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved by the authors. The rights of each contributor to be identified as Author of their Work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Copyright © 2010, 2012 by the individual contributors.

Introduction Copyright © 2010, 2012 by S. T. Joshi.

Cover Art Copyright © 2010, 2012 by Jason Van Hollander.

With thanks to PS Publishing.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the United States.

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at: [email protected],

or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

WWW.TITANBOOKS.COM

CONTENTS

Introduction

S. T. Joshi

Pickman’s Other Model (1929)

Caitlín R. Kiernan

Desert Dreams

Donald R. Burleson

Engravings

Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.

Copping Squid

Michael Shea

Passing Spirits

Sam Gafford

The Broadsword

Laird Barron

Usurped

William Browning Spencer

Denker’s Book

David J. Schow

Inhabitants of Wraithwood

W. H. Pugmire

The Dome

Mollie L. Burleson

Rotterdam

Nicholas Royle

Tempting Providence

Jonathan Thomas

Howling in the Dark

Darrell Schweitzer

The Truth about Pickman

Brian Stableford

Tunnels

Philip Haldeman

The Correspondence of Cameron Thaddeus Nash

Annotated by Ramsey Campbell

Violence, Child of Trust

Michael Cisco

Lesser Demons

Norman Partridge

An Eldritch Matter

Adam Niswander

Substitution

Michael Marshall Smith

Susie

Jason Van Hollander

Introduction

S. T. JOSHI

THE FACT THAT H. P. LOVECRAFT’S WORK HAS INSPIRED writers ranging from Jorge Luis Borges to Hugh B. Cave, from Thomas Pynchon to Brian Lumley, suggests at a minimum a widely diverse appeal ranging from the highest of highbrow writers to the lowest of the low. In his own day, Lovecraft attracted a cadre of colleagues and disciples—Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, August Derleth, Donald Wandrei, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and many others—who readily borrowed his manner, his style, and some of the components of his evolving pseudomythology; in several cases, Lovecraft returned the favor by lifting elements from their own tales. After his death in 1937, his work—first issued in hardcover by Arkham House and, over the course of the next seventy years, distributed in the millions of copies in paperback and translated in as many as thirty languages—continued to nurture the imaginations of successive generations of writers, chiefly but by no means exclusively in the realms of horror and science fiction.

What is it about Lovecraft’s work that writers find so compelling? A generation or two ago the answer would have been relatively simple: his somewhat flamboyant style mingled with his bizarre theogony of Cthulhu, Yog-Sothoth, Nyarlathotep, and so forth. Today the answer is not so straightforward. We have, mercifully, gone beyond the stage where Lovecraft’s prose style is an object of emulation—not because it is a “poor” style, but precisely because it is so intimately fused with his conceptions and worldview that imitation becomes both impossible and absurd. It is as if one were to imitate a painter’s distinctive pigments without any attempt to duplicate his models or landscapes. Similarly, the pseudomythology that Lovecraft developed in story after story is so quintessential an expression of his cosmic vision that the mere citation of a deity or place-name, without the strong philosophical foundation that Lovecraft was always careful to establish, can quickly cause a story to become a caricature of Lovecraft rather than an homage to him. It is to be noted how many stories in this anthology do not mention a single such name from the Lovecraft corpus; and yet they remain intimately Lovecraftian on a far deeper level. Indeed, the very notion of writing a “pastiche” that does little but rework Lovecraft’s own themes and ideas has now become passé in serious weird writing. Contemporary writers feel the need to express their own conceptions in their own language. The concerns of our own day demand to be treated in the language of our time, but Lovecraft’s core tenets—cosmicism; the horrors of human and cosmic history; the overtaking of the human psyche by alien incursion—remain eternally viable and can even gain a surprising relevance in the wake of such cosmic phenomena as global warming or the continuing probing of deep space.

The epigraph from “Supernatural Horror in Literature” from which I have derived the title of this book was meant by Lovecraft to be a general formula governing the best weird fiction from the dawn of time to his own day; but it is clear, from such phrases as “contact with unknown spheres and powers” and “the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim,” that the formula applies most particularly to his own work. The core of that work, as Lovecraft well recognized, was cosmicism—a conception expressed in his now celebrated letter to Farnsworth Wright of July 5, 1927, accompanying the resubmission of his seminal tale “The Call of Cthulhu” to Weird Tales: “All my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.” It was this single statement that led me, in soliciting stories for this book, to suggest that straightforward “Cthulhu Mythos” stories were not the only ones that would be considered for inclusion. It can readily be seen that some writers have chosen to play ingenious variations off of other Lovecraft tales whose relation to his mythos is tangential at best. The fact that three separate writers in this volume (Caitlín R. Kiernan, W. H. Pugmire, and Brian Stableford) have chosen to compose ingenious and widely differing riffs on such a story as “Pickman’s Model”—a tale that has only the most remote connection to the “Cthulhu Mythos” as conventionally conceived—suggests that they do not require the presence of Cthulhu or Arkham to justify their tributes. It is for this reason that I have carefully chosen my subtitle, “New Tales of Lovecraftian Horror.”

It is of interest that some of these tales effect a distinctive union between Lovecraftian horror and what seem at the outset to be very different modes of writing—the hard-boiled crime story (Norman Partridge’s “Lesser Demons”), the tale of psychological terror (Michael Cisco’s “Violence, Child of Trust”), the contemporary tale of urban blight and crime (Michael Shea’s “Copping Squid” Joseph S. Pulver, Sr.’s “Engravings”). What this suggests is that the Lovecraftian idiom is adaptable to a variety of literary modes, as Borges’s “There Are More Things” and Pynchon’s Against the Day are alone sufficient to testify. Even those tales that seem to adhere most closely to their Lovecraftian originals are distinguished by innovations in approach and outlook. Nicholas Royle has made use of the setting of Lovecraft’s “The Hound” in his story “Rotterdam,” but there is little else in this subtle and atmospheric tale that recalls the over-the-top pulpishness of its putative source.

The sense of place that was so integral a feature of Lovecraft’s personal and literary vision, and that has caused such imaginary realms as Arkham or Innsmouth to seem so throbbingly real, is similarly reflected in many of the tales in this volume. The San Francisco of Michael Shea’s “Copping Squid,” the Southwest in the tales of Donald R. and Mollie L. Burleson, the Pacific Northwest of Laird Barron’s and Philip Haldeman’s stories are all as vivid as the New England milieu of Lovecraft’s most representative tales, and as firmly based upon the authors’ experience. It would, indeed, be misleading to suggest that these writers were seeking merely to transport Lovecraft’s topographical verisimilitude into their own chosen regions; rather may it be said that the vitality of these settings is a product of their authors’ awareness of the degree to which Lovecraft’s historical and topographical richness allows—perhaps paradoxically—for an even more breathtaking cosmicism than the never-never-land of Poe.

One of the most interesting phenomena of recent years—although it may perhaps be traced all the way back to Edith Miniter’s piquant parody, “Falco Ossifracus: By Mr. Goodguile” (1921)—is the way in which Lovecraft himself has taken on the role of a fictional character. Even during his lifetime he was regarded by his fans as a larger-than-life figure—the gaunt, lantern-jawed recluse who only wrote at night and who haunted the streets of Providence in solitary state just as his idol Poe had done nearly a century before. There are serious errors in some facets of this characterization (anyone who studies Lovecraft’s two years in New York will know how gregarious he was in his meetings with the Kalem Club), but this image has worked in tandem with Lovecraft’s stories to fashion an imaginative portrait of what a horror writer should be. The materialistic and atheistic Lovecraft might not have appreciated his resurrection as a ghost in such a story as Jonathan Thomas’s “Tempting Providence,” but he would certainly have echoed the devotion to his native city that the Lovecraftian specter in this tale exhibits. Jason Van Hollander’s “Susie” brings Lovecraft’s mentally disturbed mother to life as a means of accounting, at least in part, for the particular form that Lovecraft’s imagination took in later years. And Sam Gafford’s unclassifiable “Passing Spirits” breaks down the barrier between psychological horror and supernatural horror, and perhaps even between fiction and reality, in a tale whose poignancy and sense of inexorable doom dimly echo the fate of Lovecraft’s cadre of hapless protagonists.

Cumulatively, it may at first glance appear that the stories in this volume are so diverse in tone, style, mood, and atmosphere as to be a kind of nuclear chaos. But if so, it is only a testament to the breadth of imaginative scope presented by the Lovecraftian corpus of fiction. It is also, perhaps, a testament to the starkly contrasting ways in which contemporary writers can draw upon Lovecraft to express their own conceptions and their own visions by using his work as a touchstone. If this is the case, then it augurs well for Lovecraft’s endurance among both readers and writers throughout the twenty-first century.

S. T. Joshi

“The one test of the really weird is simply this—whether or not there be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.”

H. P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature”

Pickman’s Other Model (1929)

CAITLIN R. KIERNAN

Caitlín R. Kiernan is one of the most popular and critically acclaimed writers in contemporary horror fiction. She is the author of the story collections To Charles Fort, with Love (Subterranean Press, 2005) and Tales of Pain and Wonder (Subterranean Press, 2000; rev. ed. 2008) and the novels Silk (Penguin/Roc, 1998; winner of the Barnes & Noble Maiden Voyage Award for best first novel), Threshold (Penguin/Roc, 2001), Low Red Moon (Penguin/Roc, 2003), Murder of Angels (Penguin/Roc, 2004), and Daughter of Hounds (Penguin/Roc, 2007). She has also novelized the recent film Beowulf (HarperEntertainment, 2007). She is a four-time winner of the International Horror Guild Award.

IHAVE NEVER BEEN MUCH FOR THE MOVIES, PREFERRING, instead, to take my entertainment in the theater, always favoring living actors over those flickering, garish ghosts magnified and splashed across the walls of dark and smoky rooms at twenty-four frames per second. I’ve never seemed able to get past the knowledge that the apparent motion is merely an optical illusion, a clever procession of still images streaming past my eye at such a rate of speed that I only perceive motion where none actually exists. But in the months before I finally met Vera Endecott, I found myself drawn with increasing regularity to the Boston movie houses, despite this long-standing reservation.

I had been shocked to my core by Thurber’s suicide, though, with the unavailing curse of hindsight, it’s something I should certainly have had the presence of mind to have seen coming. Thurber was an infantryman during the war—La Guerre pour la Civilisation, as he so often called it. He was at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel when Pershing failed in his campaign to seize Metz from the Germans, and he survived only to see the atrocities at the Battle of the Argonne Forest less than two weeks later. When he returned home from France early in 1919, Thurber was hardly more than a fading, nervous echo of the man I’d first met during our college years at the Rhode Island School of Design, and, on those increasingly rare occasions when we met and spoke, more often than not our conversations turned from painting and sculpture and matters of aesthetics to the things he’d seen in the muddy trenches and ruined cities of Europe.

And then there was his dogged fascination with that sick bastard Richard Upton Pickman, an obsession that would lead quickly to what I took to be no less than a sort of psychoneurotic fixation on the man and the blasphemies he committed to canvas. When, two years ago, Pickman vanished from the squalor of his North End “studio,” never to be seen again, this fixation only worsened, until Thurber finally came to me with an incredible, nightmarish tale which, at the time, I could only dismiss as the ravings of a mind left unhinged by the bloodshed and madness and countless wartime horrors he’d witnessed along the banks of the Meuse River and then in the wilds of the Argonne Forest.

But I am not the man I was then, that evening we sat together in a dingy tavern near Faneuil Hall (I don’t recall the name of the place, as it wasn’t one of my usual haunts). Even as William Thurber was changed by the war and by whatever it is he may have experienced in the company of Pickman, so too have I been changed, and changed utterly, first by Thurber’s sudden death at his own hands and then by a film actress named Vera Endecott. I do not believe that I have yet lost possession of my mental faculties, and if asked, I would attest before a judge of law that my mind remains sound, if quite shaken. But I cannot now see the world around me the way I once did, for having beheld certain things there can be no return to the unprofaned state of innocence or grace that prevailed before those sights. There can be no return to the sacred cradle of Eden, for the gates are guarded by the flaming swords of cherubim, and the mind may not—excepting in merciful cases of shock and hysterical amnesia—simply forget the weird and dismaying revelations visited upon men and women who choose to ask forbidden questions. And I would be lying if I were to claim that I failed to comprehend, to suspect, that the path I was setting myself upon when I began my investigations following Thurber’s inquest and funeral would lead me where they have. I knew, or I knew well enough. I am not yet so degraded that I am beyond taking responsibility for my own actions and the consequences of those actions.

Thurber and I used to argue about the validity of first-person narration as an effective literary device, him defending it and me calling into question the believability of such stories, doubting both the motivation of their fictional authors and the ability of those character narrators to accurately recall with such perfect clarity and detail specific conversations and the order of events during times of great stress and even personal danger. This is probably not so very different from my difficulty appreciating a moving picture because I am aware it is not, in fact, a moving picture. I suspect it points to some conscious unwillingness or unconscious inability, on my part, to effect what Coleridge dubbed the “suspension of disbelief.” And now I sit down to write my own account, though I attest there is not a word of intentional fiction to it, and I certainly have no plans of ever seeking its publication. Nonetheless, it will undoubtedly be filled with inaccuracies following from the objections to a first-person recital that I have already belabored above. What I am putting down here is my best attempt to recall the events preceding and surrounding the murder of Vera Endecott, and it should be read as such.

It is my story, presented with such meager corroborative documentation as I am here able to provide. It is some small part of her story, as well, and over it hang the phantoms of Pickman and Thurber. In all honesty, already I begin to doubt that setting any of it down will achieve the remedy which I so desperately desire—the dampening of damnable memory, the lessening of the hold that those memories have upon me, and, if I am most lucky, the ability to sleep in dark rooms once again and an end to any number of phobias which have come to plague me. Too late do I understand poor Thurber’s morbid fear of cellars and subway tunnels, and to that I can add my own fears, whether they might ever be proven rational or not. “I guess you won’t wonder now why I have to steer clear of subways and cellars,” he said to me that day in the tavern. I did wonder, of course, at that and at the sanity of a dear and trusted friend. But, in this matter, at least, I have long since ceased to wonder.

The first time I saw Vera Endecott on the “big screen,” it was only a supporting part in Josef von Sternberg’s A Woman of the Sea, at the Exeter Street Theater. But that was not the first time I saw Vera Endecott.

IFIRST ENCOUNTERED THE NAME AND FACE OF THE actress while sorting through William’s papers, which I’d been asked to do by the only surviving member of his immediate family, Ellen Thurber, an older sister. I found myself faced with no small or simple task, as the close, rather shabby room he’d taken on Hope Street in Providence after leaving Boston was littered with a veritable bedlam of correspondence, typescripts, journals, and unfinished compositions, including the monograph on weird art that had played such a considerable role in his taking up with Richard Pickman three years prior. I was only mildly surprised to discover, in the midst of this disarray, a number of Pickman’s sketches, all of them either charcoal or pen and ink. Their presence among Thurber’s effects seemed rather incongruous, given how completely terrified of the man he’d professed to having become. And even more so given his claim to have destroyed the one piece of evidence that could support the incredible tale of what he purported to have heard and seen and taken away from Pickman’s cellar studio.

It was a hot day, so late into July that it was very nearly August. When I came across the sketches, seven of them tucked inside a cardboard portfolio case, I carried them across the room and spread the lot out upon the narrow, swaybacked bed occupying one corner. I had a decent enough familiarity with the man’s work, and I must confess that what I’d seen of it had never struck me quiet so profoundly as it had Thurber. Yes, to be sure, Pickman was possessed of a great and singular talent, and I suppose someone unaccustomed to images of the diabolic, the alien or monstrous, would find them disturbing and unpleasant to look upon. I always credited his success at capturing the weird largely to his intentional juxtaposition of phantasmagoric subject matter with a starkly, painstakingly realistic style. Thurber also noted this and, indeed, had devoted almost a full chapter of his unfinished monograph to an examination of Pickman’s technique.

I sat down on the bed to study the sketches, and the mattress springs complained loudly beneath my weight, leading me to wonder yet again why my friend had taken such mean accommodations when he certainly could have afforded better. At any rate, glancing over the drawings, they struck me, for the most part, as nothing particularly remarkable, and I assumed that they must have been gifts from Pickman, or that Thurber might even have paid him some small sum for them. Two I recognized as studies for one of the paintings mentioned that day in the Chatham Street tavern, the one titled “The Lesson,” in which the artist had sought to depict a number of his subhuman, dog-like ghouls instructing a young child (a changeling, Thurber had supposed) in their practice of necrophagy. Another was a rather hasty sketch of what I took to be some of the statelier monuments in Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, and there were also a couple of rather slapdash renderings of hunched gargoyle-like creatures.

But it was the last two pieces from the folio that caught and held my attention. Both were very accomplished nudes, more finished than any of the other sketches, and given the subject matter, I might have doubted they had come from Pickman’s hand had it not been for his signature at the bottom of each. There was nothing that could have been deemed pornographic about either, and considering their provenance, this surprised me, as well. Of the portion of Richard Pickman’s oeuvre that I’d seen for myself, I’d not once found any testament to an interest in the female form, and there had even been whispers in the Art Club that he was a homosexual. But there were so many rumors traded about the man in the days leading up to his disappearance, many of them plainly spurious, that I’d never given the subject much thought. Regardless of his own sexual inclinations, these two studies were imbued with an appreciation and familiarity with a woman’s body that seemed unlikely to have been gleaned entirely from academic exercises or mooched from the work of other, less eccentric artists.

As I inspected the nudes, thinking that these two pieces, at least, might bring a few dollars to help Thurber’s sister cover the unexpected expenses incurred by her brother’s death, as well as his outstanding debts, my eyes were drawn to a bundle of magazine and newspaper clippings that had also been stored inside the portfolio. There were a goodly number of them, and I guessed then, and still suppose, that Thurber had employed a clipping bureau. About half of them were writeups of gallery showings that had included Pickman’s work, mostly spanning the years from 1921 to 1925, before he’d been so ostracized that opportunities for public showings had dried up. But the remainder appeared to have been culled largely from tabloids, sheetlets, and magazines such as Photoplay and the New York Evening Graphic, and every one of the articles was either devoted to or made mention of a Massachusetts-born actress named Vera Marie Endecott. There were, among these clippings, a number of photographs of the woman, and her likeness to the woman who’d modeled for the two Pickman nudes was unmistakable.

There was something quite distinct about her high cheekbones, the angle of her nose, an undeniable hardness to her countenance despite her starlet’s beauty and “sex appeal.” Later, I would come to recognize some commonality between her face and those of such movie “vamps” and femme fatales as Theda Bara, Eva Galli, Musidora, and, in particular, Pola Negri. But, as best as I can now recollect, my first impression of Vera Endecott, untainted by film personae (though undoubtedly colored by the association of the clippings with the work of Richard Pickman, there among the belongings of a suicide), was of a woman whose loveliness might merely be a glamour concealing some truer, feral face. It was an admittedly odd impression, and I sat in the sweltering boardinghouse room, as the sun slid slowly toward dusk, reading each of the articles, and then reading some over again. I suspected they must surely contain, somewhere, evidence that the woman in the sketches was, indeed, the same woman who’d gotten her start in the movie studios of Long Island and New Jersey, before the industry moved west to California.

For the most part, the clippings were no more than the usual sort of picture-show gossip, innuendo, and sensationalism. But, here and there, someone, presumably Thurber himself, had underlined various passages with a red pencil, and when those lines were considered together, removed from the context of their accompanying articles, a curious pattern could be discerned. At least, such a pattern might be imagined by a reader who was either searching for it, and so predisposed to discovering it whether it truly existed or not, or by someone, like myself, coming to these collected scraps of yellow journalism under such circumstances and such an atmosphere of dread as may urge the reader to draw parallels where, objectively, there are none to be found. I believed, that summer afternoon, that Thurber’s idée fixe with Richard Pickman had led him to piece together an absurdly macabre set of notions regarding this woman, and that I, still grieving the loss of a close friend and surrounded as I was by the disorder of that friend’s unfulfilled life’s work, had done nothing but uncover another of Thurber’s delusions.

The woman known to moviegoers as Vera Endecott had been sired into an admittedly peculiar family from the North Shore region of Massachusetts, and she’d undoubtedly taken steps to hide her heritage, adopting a stage name shortly after her arrival in Fort Lee in February of 1922. She’d also invented a new history for herself, claiming to hail not from rural Essex County, but from Boston’s Beacon Hill. However, as early as ’24, shortly after landing her first substantial role—an appearance in Biograph Studios’ Sky Below the Lake—a number of popular columnists had begun printing their suspicions about her professed background. The banker she’d claimed as her father could not be found, and it proved a straightforward enough matter to demonstrate that she’d never attended the Winsor School for girls. By ’25, after starring in Robert G. Vignola’s The Horse Winter, a reporter for the New York Evening Graphic claimed Endecott’s actual father was a man named Iscariot Howard Snow, the owner of several Cape Anne granite quarries. His wife, Make-peace, had come either from Salem or Marblehead, and had died in 1902 while giving birth to their only daughter, whose name was not Vera, but Lillian Margaret. There was no evidence in any of the clippings that the actress had ever denied or even responded to any of these allegations, despite the fact that the Snows, and Iscariot Snow in particular, had a distinctly unsavory reputation in and around Ipswich. Despite the family’s wealth and prominence in local business, it was notoriously secretive, and there was no want for back-fence talk concerning sorcery and witchcraft, incest, and even cannibalism. In 1899, Make-peace Snow had also borne twin sons, Aldous and Edward, though Edward had been a stillbirth.

But it was a clipping from Kidder’s Weekly Art News (March 27, 1925), a publication I was well enough acquainted with, that first tied the actress to Richard Pickman. A “Miss Vera Endecott of Manhattan” was listed among those in attendance at the premiere of an exhibition that had included a couple of Pickman’s less provocative paintings, though no mention was made of her celebrity. Thurber had circled her name with his red pencil and drawn two exclamation points beside it. By the time I came across the article, twilight had descended upon Hope Street, and I was having trouble reading. I briefly considered the old gas lamp near the bed, but then, staring into the shadows gathering amongst the clutter and threadbare furniture of the seedy little room, I was gripped by a sudden, vague apprehension—by what, even now, I am reluctant to name fear. I returned the clippings and the seven sketches to the folio, tucked it under my arm, and quickly retrieved my hat from a table buried beneath a typewriter, an assortment of paper and library books, unwashed dishes and empty soda bottles. A few minutes later, I was outside again and clear of the building, standing beneath a streetlight, staring up at the two darkened windows opening into the room where, a week before, William Thurber had put the barrel of a revolver in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

IHAVE JUST AWAKENED FROM ANOTHER OF MY nightmares, which become ever more vivid and frequent, ever more appalling, often permitting me no more than one or two hours sleep each night. I’m sitting at my writing desk, watching as the sky begins to go the grey-violet of false dawn, listening to the clock ticking like some giant wind-up insect perched upon the mantle. But my mind is still lodged firmly in a dream of the musty private screening room near Harvard Square, operated by a small circle of aficionados of grotesque cinema, the room where first I saw “moving” images of the daughter of Iscariot Snow.

I’d learned of the group from an acquaintance in acquisitions at the Museum of Fine Arts, who’d told me it met irregularly, rarely more than once every three months, to view and discuss such fanciful and morbid fare as Benjamin Christensen’s Häxen, Rupert Julian’s The Phantom of the Opera, Murnau’s Nosferatu—Eine Symphonie des Grauens, and Todd Browning’s London After Midnight. These titles and the names of their directors meant very little to me, since, as I have already noted, I’ve never been much for the movies. This was in August, only a couple of weeks after I’d returned to Boston from Providence, having set Thurber’s affairs in order as best I could. I still prefer not to consider what unfortunate caprice of fate aligned my discovery of Pickman’s sketches of Vera Endecott and Thurber’s interest in her with the group’s screening of what, in my opinion, was a profane and a deservedly unheard-of film. Made sometime in 1923 or ’24, I was informed that it had achieved infamy following the director’s death (another suicide). All the film’s financiers remained unknown, and it seemed that production had never proceeded beyond the incomplete rough cut I saw that night.

However, I did not sit down here to write out a dry account of my discovery of this untitled, unfinished film, but rather to try and capture something of the dream that is already breaking into hazy scraps and shreds. Like Perseus, who dared to view the face of the Gorgon Medusa only indirectly, as a reflection in his bronze shield, so I seem bound and determined to reflect upon these events, and even my own nightmares, as obliquely as I may. I have always despised cowardice, and yet, looking back over these pages, there seems in it something undeniably cowardly. It does not matter that I intend that no one else shall ever read this. Unless I write honestly, there is hardly any reason in writing it at all. If this is a ghost story (and, increasingly, it feels that way to me), then let it be a ghost story, and not this rambling reminiscence.

In the dream, I am sitting in a wooden folding chair in that dark room, lit only by the single shaft of light spilling forth from the projectionist’s booth. And the wall in front of me has become a window, looking out upon or into another world, one devoid of sound and almost all color, its palette limited to a spectrum of somber blacks and dazzling whites and innumerable shades of grey. Around me, the others who have come to see smoke their cigars and cigarettes, and they mutter among themselves. I cannot make out anything they say, but, then, I’m not trying particularly hard. I cannot look away from that that silent, grisaille scene, and little else truly occupies my mind.

“Now, do you understand?” Thurber asks from his seat next to mine, and maybe I nod, and maybe I even whisper some hushed affirmation or another. But I do not take my eyes from the screen long enough to glimpse his face. There is too much there I might miss, were I to dare look away, even for an instant, and, moreover, I have no desire to gaze upon the face of a dead man. Thurber says nothing else for a time, apparently content that I have found my way to this place, to witness for myself some fraction of what drove him, at last, to the very end of madness.

She is there on the screen—Vera Endecott, Lillian Margaret Snow—standing at the edge of a rocky pool. She is as naked as in Pickman’s sketches of her, and is positioned, at first, with her back to the camera. The gnarled roots and branches of what might be ancient willow trees bend low over the pool, their whiplike branches brushing the surface and moving gracefully too and fro, disturbed by the same breeze that ruffles the actress’ short, bob-cut hair. And though there appears to be nothing the least bit sinister about this scene, it at once inspires in me the same sort of awe and uneasiness as Doré’s engravings for Orlando Furioso and the Divine Comedy. There is about the tableau a sense of intense foreboding and anticipation, and I wonder what subtle, clever cues have been placed just so that this seemingly idyllic view would be interpreted with such grim expectancy.

And then I realize that the actress is holding in her right hand some manner of phial, and she tilts it just enough that the contents, a thick and pitchy liquid, drips into the pool. Concentric ripples spread slowly across the water, much too slowly, I’m convinced, to have followed from any earthly physics, and so I dismiss it as merely trick photography. When the phial is empty, or has, at least, ceased to taint the pool (and I am quite sure that it has been tainted), the woman kneels in the mud and weeds at the water’s edge. From somewhere overhead, there in the room with me, comes a sound like the wings of startled pigeons taking flight, and the actress half turns toward the audience, as if she has also somehow heard the commotion. The fluttering racket quickly subsides, and once more there is only the mechanical noise from the projector and the whispering of the men and women crowded into the musty room. Onscreen, the actress turns back to the pool, but not before I am certain that her face is the same one from the clippings I found in Thurber’s room, the same one sketched by the hand of Richard Upton Pickman. The phial slips from her fingers, falling into the water, and this time there are no ripples whatsoever. No splash. Nothing.

Here, the image flickers before the screen goes blinding white, and I think, for a moment, that the filmstrip has, mercifully, jumped one sprocket or another, so maybe I’ll not have to see the rest. But then she’s back, the woman and the pool and the willows, playing out frame by frame by frame. She kneels at the edge of the pool, and I think of Narcissus pining for Echo or his lost twin, of jealous Circe poisoning the spring where Scylla bathed, and of Tennyson’s cursed Shalott, and, too, again I think of Perseus and Medusa. I am not seeing the thing itself, but only some dim, misguiding counterpart, and my mind grasps for analogies and signification and points of reference.

On the screen, Vera Endecott, or Lillian Margaret Snow—one or the other, the two who were always only one—leans forward and dips her hand into the pool. And again, there are no ripples to mar its smooth obsidian surface. The woman in the film is speaking now, her lips moving deliberately, making no sound whatsoever, and I can hear nothing but the mumbling, smoky room and the sputtering projector. And this is when I realize that the willows are not precisely willows at all, but that those twisted trunks and limbs and roots are actually the entwined human bodies of both sexes, their skin perfectly mimicking the scaly bark of a willow. I understand that these are no wood nymphs, no daughters of Hamadryas and Oxylus. These are prisoners, or condemned souls bound eternally for their sins, and for a time I can only stare in wonder at the confusion of arms and legs, hips and breasts and faces marked by untold ages of the ceaseless agony of this contortion and transformation. I want to turn and ask the others if they see what I see, and how the deception has been accomplished, for surely these people know more of the prosaic magic of filmmaking that do I. Worst of all, the bodies have not been rendered entirely inert, but writhe ever so slightly, helping the wind to stir the long, leafy branches first this way, then that.

Then my eye is drawn back to the pool, which has begun to steam, a grey-white mist rising languidly from off the water (if it is still water). The actress leans yet farther out over the strangely quiescent mere, and I find myself eager to look away. Whatever being the cameraman has caught her in the act of summoning or appeasing, I do not want to see, do not want to know its daemonic physiognomy. Her lips continue to move, and her hands stir the waters that remain smooth as glass, betraying no evidence that they have been disturbed in any way.

At Rhegium she arrives; the ocean braves,

And treads with unwet feet the boiling waves...

But desire is not enough, nor trepidation, and I do not look away, either because I have been bewitched along with all those others who have come to see her, or because some deeper, more disquisitive facet of my being has taken command and is willing to risk damnation in the seeking into this mystery.

“It is only a moving picture,” dead Thurber reminds me from his seat beside mine. “Whatever else she would say, you must never forget it is only a dream.”

And I want to reply, “Is that what happened to you, dear William? Did you forget it was never anything more than a dream and find yourself unable to waken to lucidity and life?” But I do not say a word, and Thurber does not say anything more.

But yet she knows not, who it is she fears;

In vain she offers from herself to run,

And drags about her what she strives to shun.

“Brilliant,” whispers a woman in the darkness at my back, and “Sublime,” mumbles what sounds like a very old man. My eyes do not stray from the screen. The actress has stopped stirring the pool, has withdrawn her hand from the water, but still she kneels there, staring at the sooty stain it has left on her fingers and palm and wrist. Maybe, I think, that is what she came for, that mark, that she will be known, though my dreaming mind does not presume to guess what or whom she would have recognize her by such a bruise or blotch. She reaches into the reeds and moss and produces a black-handled dagger, which she then holds high above her head, as though making an offering to unseen gods, before she uses the glinting blade to slice open the hand she previously offered to the waters. And I think perhaps I understand, finally, and the phial and the stirring of the pool were only some preparatory wizardry before presenting this far more precious alms or expiation. As her blood drips to spatter and roll across the surface of the pool like drops of mercury striking a solid tabletop, something has begun to take shape, assembling itself from those concealed depths, and, even without sound, it is plain enough that the willows have begun to scream and to sway as though in the grip of a hurricane wind. I think, perhaps, it is a mouth, of sorts, coalescing before the prostrate form of Vera Endecott or Lillian Margaret Snow, a mouth or a vagina or a blind and lidless eye, or some organ that may serve as all three. I debate each of these possibilities, in turn.

Five minutes ago, almost, I lay my pen aside, and I have just finished reading back over, aloud, what I have written, as false dawn gave way to sunrise and the first uncomforting light of a new October day. But before I return these pages to the folio containing Pickman’s sketches and Thurber’s clippings and go on about the business that the morning demands of me, I would confess that what I have dreamed and what I have recorded here are not what I saw that afternoon in the screening room near Harvard Square. Neither is it entirely the nightmare that woke me and sent me stumbling to my desk. Too much of the dream deserted me, even as I rushed to get it all down, and the dreams are never exactly, and sometimes not even remotely, what I saw projected on that wall, that deceiving stream of still images conspiring to suggest animation. This is another point I always tried to make with Thurber, and which he never would accept, the fact of the inevitability of unreliable narrators. I have not lied; I would not say that. But none of this is any nearer to the truth than any other fairy tale.

AFTER THE DAYS I SPENT IN THE BOARDING-HOUSE IN Providence, trying to bring some semblance of order to the chaos of Thurber’s interrupted life, I began accumulating my own files on Vera Endecott, spending several days in August drawing upon the holdings of the Boston Athenaeum, Public Library, and the Widener Library at Harvard. It was not difficult to piece together the story of the actress’ rise to stardom and the scandal that led to her descent into obscurity and alcoholism late in 1927, not so very long before Thurber came to me with his wild tale of Pickman and subterranean ghouls. What was much more difficult to trace was her movement through certain theosophical and occult societies, from Manhattan to Los Angeles, circles to which Richard Upton Pickman was, himself, no stranger.

In January ’27, after being placed under contract to Paramount Pictures the previous spring, and during production of a film adaptation of Margaret Kennedy’s novel, The Constant Nymph, rumors began surfacing in the tabloids that Vera Endecott was drinking heavily and, possibly, using heroin. However, these allegations appear at first to have caused her no more alarm or damage to her film career than the earlier discovery that she was, in fact, Lillian Snow, or the public airing of her disreputable North Shore roots. Then, on May 3rd, she was arrested in what was, at first, reported as merely a raid on a speakeasy somewhere along Durand Drive, at an address in the steep, scrubby canyons above Los Angeles, nor far from the Lake Hollywood Reservoir and Mulholland Highway. A few days later, after Endecott’s release on bail, queerer accounts of the events of that night began to surface, and by the 7th, articles in the Van Nuys Call, Los Angeles Times, and the Herald-Express were describing the gathering on Durand Drive not as a speakeasy, but as everything from a “witches’ Sabbat” to “a decadent, sacrilegious, orgiastic rite of witchcraft and homosexuality.”

But the final, damning development came when reporters discovered that one of the many women found that night in the company of Vera Endecott, a Mexican prostitute named Ariadna Delgado, had been taken immediately to Queen of Angels–Hollywood Presbyterian, comatose and suffering from multiple stab wounds to her torso, breasts, and face. Delgado died on the morning of May 4th, without ever having regained consciousness. A second “victim” or “participant” (depending on the newspaper), a young and unsuccessful screenwriter listed only as Joseph E. Chapman, was placed in the psychopathic ward of LA County General Hospital following the arrests.

Though there appear to have been attempts to keep the incident quiet by both studio lawyers and also, perhaps, members of the Los Angeles Police Department, Endecott was arrested a second time on May 10th and charged with multiple counts of rape, sodomy, second-degree murder, kidnapping, and solicitation. Accounts of the specific charges brought vary from one source to another, but regardless, Endecott was granted and made bail a second time on May 11th, and four days later, the office of Los Angeles District Attorney Asa Keyes abruptly and rather inexplicably asked for a dismissal of all charges against the actress, a motion granted in an equally inexplicable move by the Superior Court of California, Los Angeles County (it bears mentioning, of course, that District Attorney Keyes was, himself, soon thereafter indicted for conspiracy to receive bribes and is presently awaiting trial). So, eight days after her initial arrest at the residence on Durand Drive, Vera Endecott was a free woman, and by late May she had returned to Manhattan, after her contract with Paramount was terminated.

Scattered throughout the newspaper and tabloid coverage of the affair are numerous details that take on a greater significance in light of her connection with Richard Pickman. For one, some reporters made mention of “an obscene idol” and “a repellent statuette carved from something like greenish soapstone” recovered from the crime scene, a statue which one of the arresting officer’s is purported to have described as a “crouching, doglike beast.” One article listed the item as having been examined by a local (unnamed) archeologist, who was supposedly baffled at its origins and cultural affinities. The house on Durand Drive was, and may still be, owned by a man named Beauchamp who had spent time in the company of Aleister Crowley during his four-year visit to America (1914– 1918), and who had connections with a number of hermetic and theurgical organizations. And finally, the screenwriter Joseph Chapman drowned himself in the Pacific somewhere near Malibu only a few months ago, shortly after being discharged from the hospital. The one short article I could locate regarding his death made mention of his part in the “notorious Durand Drive incident” and printed a short passage reputed to have come from the suicide note. It reads, in part, as follows:

Oh God, how does a man forget, deliberately and wholly and forever, once he has glimpsed such sights as I have had the misfortune to have seen? The awful things we did and permitted to be done that night, the events we set in motion, how do I lay my culpability aside? Truthfully, I cannot and am no longer able to fight through day after day of trying. The Endecotte [sic] woman is back East somewhere, I hear, and I hope to hell she gets what’s coming to her. I burned the abominable painting she gave me, but I feel no cleaner, no less foul, for having done so. There is nothing left of me but the putrescence we invited. I cannot do this anymore.

Am I correct in surmising, then, that Vera Endecott made a gift of one of Pickman’s paintings to the unfortunate Joseph Chapman, and that it played some role in his madness and death? If so, how many others received such gifts from her, and how many of those canvases yet survive so many thousands of miles from the dank cellar studio near Battery Street where Pickman created them? It’s not something I like to dwell upon.

After Endecott’s reported return to Manhattan, I failed to find any printed record of her whereabouts or doings until October of that year, shortly after Pickman’s disappearance and my meeting with Thurber in the tavern near Faneuil Hall. It’s only a passing mention from a society column in the New York Herald Tribune, that “the actress Vera Endecott” was among those in attendance at the unveiling of a new display of Sumerian, Hittite, and Babylonian antiquities at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What is it I am trying to accomplish with this catalogue of dates and death and misfortune, calamity and crime? Among Thurber’s books, I found a copy of Charles Hoyt Fort’s The Book of the Damned (New York: Boni & Liveright, December 1, 1919). I’m not even sure why I took it away with me, and having read it, I find the man’s writings almost hysterically belligerant and constantly prone to intentional obfuscation and misdirection. Oh, and wouldn’t that contentious bastard love to have a go at this tryst with “the damned”? My point here is that I’m forced to admit that these last few pages bear a marked and annoying similarity to much of Fort’s first book (I have not read his second, New Lands, nor do I propose ever to do so). Fort wrote of his intention to present a collection of data that had been excluded by science (id est, “damned”):

Battalions of the accursed, captained by pallid data that I have exhumed, will march. You’ll read them—or they’ll march. Some of them livid and some of them fiery and some of them rotten.

Some of them are corpses, skeletons, mummies, twitching, tottering, animated by companions that have been damned alive. There are giants that will walk by, though sound asleep. There are things that are theorems and things that are rags: they’ll go by like Euclid arm in arm with the spirit of anarchy. Here and there will flit little harlots. Many are clowns. But many are of the highest respectability. Some are assassins. There are pale stenches and gaunt superstitions and mere shadows and lively malices: whims and amiabilities. The naïve and the pedantic and the bizarre and the grotesque and the sincere and the insincere, the profound and the puerile.

And I think I have accomplished nothing more than this, in my recounting of Endecott’s rise and fall, drawing attention to some of the more melodramatic and vulgar parts of a story that is, in the main, hardly more remarkable than numerous other Hollywood scandals. But also, Fort would laugh at my own “pallid data,” I am sure, my pathetic grasping at straws, as though I might make this all seem perfectly reasonable by selectively quoting newspapers and police reports, straining to preserve the fraying infrastructure of my rational mind. It’s time to lay these dubious, slipshod attempts at scholarship aside. There are enough Forts in the world already, enough crackpots and provocateurs and intellectual heretics without my joining their ranks. The files I have assembled will be attached to this document, all my “Battalions of the accursed,” and if anyone should ever have cause to read this, they may make of those appendices what they will. It’s time to tell the truth, as best I am able, and be done with this.

IT IS TRUE THAT I ATTENDED A SCREENING OF A FILM, featuring Vera Endecott, in a musty little room near Harvard Square. And that it still haunts my dreams. But as noted above, the dreams rarely are anything like an accurate replaying of what I saw that night. There was no black pool, no willow trees stitched together from human bodies, no venomous phial emptied upon the waters. Those are the embellishments of my dreaming, subconscious mind. I could fill several journals with such nightmares.

What I did see, only two months ago now, and one month before I finally met the woman for myself, was little more than a grisly, but strangely mundane, scene. It might have only been a test reel, or perhaps 17,000 or so frames, some twelve minutes, give or take, excised from a far longer film. All in all, it was little more than a blatantly pornographic pastiche of the widely circulated 1918 publicity stills of Theda Bara lying in various risqué poses with a human skeleton (for J. Edward Gordon’s Salomé).

The print was in very poor condition, and the projectionist had to stop twice to splice the film back together after it broke. The daughter of Iscariot Snow, known to most of the world as Vera Endecott, lay naked upon a stone floor with a skeleton. However, the human skull had been replaced with what I assumed then (and still believe) to have been a plaster or papier-mâché “skull” that more closely resembled that of some malformed, macrocephalic dog. The wall or backdrop behind her was a stark matte-grey, and the scene seemed to me purposefully under-lit in an attempt to bring more atmosphere to a shoddy production. The skeleton (and its ersatz skull) were wired together, and Endecott caressed all the osseous angles of its arms and legs and lavished kisses upon it lipless mouth, before masturbating, first with the bones of its right hand, and then by rubbing herself against the crest of an ilium.

The reactions from the others who’d come to see the film that night ranged from bored silence to rapt attention to laughter. My own reaction was, for the most part, merely disgust and embarrassment to be counted among that audience. I overheard, when the lights came back up, that the can containing the reel bore two titles, The Necrophile and The Hound’s Daughter, and also bore two dates—1923 and 1924. Later, from someone who had a passing acquaintance with Richard Pickman, I would hear a rumor that he’d worked on scenarios for a filmmaker, possibly Bernard Natan, the prominent Franco-Romanian director of “blue movies,” who recently acquired Pathé and merged it with his own studio, Rapid Film. I cannot confirm or deny this, but certainly, I imagine what I saw that evening would have delighted Pickman no end.

However, what has lodged that night so firmly in my mind, and what I believe is the genuine author of those among my nightmares featuring Endecott in an endless parade of nonexistent horrific films, transpired only in the final few seconds of the film. Indeed, it came and went so quickly, the projectionist was asked by a number of those present to rewind and play the ending over four times, in an effort to ascertain whether we’d seen what we thought we had seen.

Her lust apparently satiated, the actress lay down with her skeletal lover, one arm about its empty ribcage, and closed her kohl-smudged eyes. And in that last instant, before the film ended, a shadow appeared, something passing slowly between the set and the camera’s light source. Even after five viewings, I can only describe that shade as having put me in mind of some hulking figure, something considerably farther down the evolutionary ladder than Piltdown or Java man. And it was generally agreed among those seated in that close and musty room that the shadow was possessed of an odd sort of snout or muzzle, suggestive of the prognathous jaw and face of the fake skull wired to the skeleton.

There, then. That is what I actually saw that evening, as best I now can remember it. Which leaves me with only a single piece of this story left to tell, the night I finally met the woman who called herself Vera Endecott.

“DISAPPOINTED? NOT QUITE WHAT YOU WERE EXPECTING?” she asked, smiling a distasteful, wry sort of smile, and I think I might have nodded in reply. She appeared at least a decade older than her twenty-seven years, looking like a woman who had survived one rather tumultuous life already and had, perhaps, started in upon a second. There were fine lines at the corners of her eyes and mouth, the bruised circles below her eyes that spoke of chronic insomnia and drug abuse, and, if I’m not mistaken, a premature hint of silver in her bobbed black hair. What had I anticipated? It’s hard to say now, after the fact, but I was surprised by her height, and by her irises, which were a striking shade of grey. At once, they reminded me of the sea, of fog and breakers and granite cobbles polished perfectly smooth by ages in the surf. The Greeks said that the goddess Athena had “sea-grey” eyes, and I wonder what they would have thought of the eyes of Lillian Snow.

“I have not been well,” she confided, making the divulgence sound almost like a mea culpa, and those stony eyes glanced toward a chair in the foyer of my flat. I apologized for not having already asked her in, for having kept her standing in the hallway. I led her to the davenport sofa in the tiny parlor off my studio, and she thanked me. She asked for whiskey or gin, and then laughed at me when I told her I was a teetotaler. When I offered her tea, she declined.

“A painter who doesn’t drink?” she asked. “No wonder I’ve never heard of you.”

I believe that I mumbled something then about the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act, which earned from her an expression of commingled disbelief and contempt. She told me that was strike two, and if it turned out that I didn’t smoke, either, she was leaving, as my claim to be an artist would have been proven a bald-faced lie, and she’d know I’d lured her to my apartment under false pretenses. But I offered her a cigarette, one of the brun Gitanes I first developed a taste for in college, and at that she seemed to relax somewhat. I lit her cigarette, and she leaned back on the sofa, still smiling that wry smile, watching me with her sea-grey eyes, her thin face wreathed in gauzy veils of smoke. She wore a yellow felt cloche that didn’t exactly match her burgundy silk chemise, and I noticed there was a run in her left stocking.

“You knew Richard Upton Pickman,” I said, blundering much too quickly to the point, and, immediately, her expression turned somewhat suspicious. She said nothing for almost a full minute, just sat there smoking and staring back at me, and I silently cursed my impatience and lack of tact. But then the smile returned, and she laughed softly and nodded.

“Wow,” she said. “There’s a name I haven’t heard in a while. But, yeah, sure, I knew the son of a bitch. So, what are you? Another of his protégés, or maybe just one of the three-letter-men he liked to keep handy?”

“Then it’s true Pickman was light on his feet?” I asked.

She laughed again, and this time there was an unmistakable edge of derision there. She took another long drag on her cigarette, exhaled, and squinted at me through the smoke.

“Mister, I have yet to meet the beast—male, female, or anything in between—that degenerate fuck wouldn’t have screwed, given half a chance.” She paused, here, tapping ash onto the floorboards. “So, if you’re not a fag, just what are you? A kike, maybe? You sort of look like a kike.”

“No,” I replied. “I’m not Jewish. My parents were Roman Catholic, but me, I’m not much of anything, I’m afraid, but a painter you’ve never heard of.”

“Are you?”

“Am I what, Miss Endecott?”

“Afraid,” she said, smoke leaking from her nostrils. “And do not dare start in calling me ‘Miss Endecott.’ It makes me sound like a goddamned schoolteacher or something equally wretched.”

“So, these days, do you prefer Vera?” I asked, pushing my luck. “Or Lillian?”

“How about Lily?” she smiled, completely nonplussed, so far as I could tell, as though these were all only lines from some script she’d spent the last week rehearsing.

“Very well, Lily,” I said, moving the glass ashtray on the table closer to her. She scowled at it, as though I were offering her a platter of some perfectly odious foodstuff and expecting her to eat, but she stopped tapping her ash on my floor.

“Why am I here?” she demanded, commanding an answer without raising her voice. “Why have you gone to so much trouble to see me?”