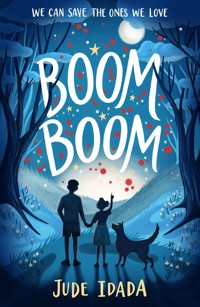

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Osaik lives a happy, charmed life, his loyal dog Kompa always by his side. But his mother suffers from sickle cell disease, and one day his world is thrown into disarray when it takes her away from him. Despite his grief, Osaik has to find a way of saving his little sister, Eghe, from the same fate. There is no time to waste as he, his dad, and the ever-faithful Kompa begin a race to get her all the help she needs. For ages 9+.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

For the warriors who have fallen and those who are still fighting.

Contents

1. Life Is Beautiful 2. The Night My Mother Slept 3. Boom Boom Is Her Pet Name 4. The Tears My Dad Shed 5. My Dad’s Heart Was Broken 6. The Test 7. London Has Spoken 8. Picking Up All the Broken Pieces 9. The Wheels Begin to Turn 10. The Search 11. The Match 12. The Transplant 13. Boom Boom Is Now a Star Acknowledgements1

Life Is Beautiful

When I was born, my mum said that I didn’t cry for five long weeks. All I did was squint and rub my tiny hands together as though praying. The nurses spanked my bare bottom, but I didn’t make a sound.

They pricked my tiny foot, and all I did was wiggle it. No matter what they did, I didn’t cry.

My mum said she and my dad were worried at first but stopped worrying because as the days passed, instead of crying, I smiled and yawned a lot. She also said that when everyone was fast asleep at night, I would burst out laughing loudly. When she woke up, she would see me staring at the ceiling as though someone hanging there was making funny faces at me; and when she tickled me on the cheek to distract me, I would look at her, smile, turn back to the ceiling and laugh even louder. At those times, my mother said I made her feel like there was a grown man hiding inside my body.

Even though they weren’t worried that I hadn’t cried for a while, they took me to the hospital because the neighbours kept on badgering them that something was wrong with me. When they got there, after I was examined by the doctor, he told them in a comforting tone: “Don’t worry, some babies just take their time. As you can see, his eyes follow you when you speak, so this baby, I must say, will be a very intelligent boy. A boy who will cry in his own time.”

When I finally cried, it was because I was hungry. So hungry that my mum had to immediately feed me with baby food because she couldn’t produce enough breast milk for me. I always wanted to suckle, and she was sore from breastfeeding me.

The doctors were surprised at my appetite but were not altogether concerned. They told my parents that over time I would develop a normal appetite for a baby my age, but I didn’t. Instead, I ate more and more until I became chubby and round as a ball.

My mum said that my laughter was usually infectious. It was the kind of laughter that made you laugh with me even if you didn’t know the reason I was laughing. She also said that though I didn’t cry early, I spoke at four months old. It was a babble that was made up mostly of the names of foods, like:

Water, Milk and Dodo.

Words like:

Hungry, Sleep and Toilet.

Soon those were followed by phrases like:

Give me, and Oops, me burp!

These words were sometimes followed by long giggles that most times transformed into lingering laughter. It was as though I wanted to make up for not crying early. My mum said she was glad that since I was already bigger than my age, she didn’t need to answer questions from people who would have been shocked that I had started to talk quite early.

I was a very big baby, so much bigger than all the babies my age that, during the days after I was born, my mum couldn’t find my size of nappies at the store, and she had to buy the size for toddlers. I grew up fast, spoke faster, and played without boundaries at every opportunity I could get. But I wasn’t fearless. I had a healthy dose of fear. But somehow, I never allowed it to hold me back. I just stared it in the face for a short while before I pushed it aside and went ahead and did what I wanted to do.

My mum said there was something about me that was attracted to exploring things, figuring them out and using them to discover even more things. I would check the shoeboxes that were kept in the storeroom at home and, upon finding them empty, I would stack them up in front of the huge wardrobe in the bedroom and climb on top of them so that my hand could reach the knob of the door. Once my hand reached it, I would open it a little bit, climb down the stacked shoeboxes, and open the door even wider before stepping inside to explore the contents. Usually, I ended up wearing a mismatch of clothes and shoes that were way too big for me, so that when I walked into the living room where my parents sat watching television, I’d draw a loud report of laughter from them.

My mum would say, as she spoke about me to her friends and our relatives, “Trust me, there is no boring day with him. When you think there is nothing crazier or funnier he could do, he will surprise you in the next instant. In fact, his dad and I already know that he’s going to be either a comedian or a soldier when he grows up. He is fearless.”

I was a quick learner. Actually, my mum said I ate knowledge like I ate food. But unlike food, which made me put on weight, knowledge made me lose all the baby fat I had. So, as I grew older, I became slimmer and taller. And my light-complexioned skin became more like the colour of chocolate, which was exactly like my mum’s, yet I looked like my dad. Everyone did say I behaved like a mix of both of them. I was caring, outgoing and fun-loving like my mum, and stubborn and courageous like my dad—but no one knew where I got the ability to hear things no one else could.

As I grew up, I surprised everyone with my claims that I could hear trees, flowers and animals talk. First, they thought I was daydreaming, and when I insisted, they would look at me, worried. It got so bad that at school, the students would crowd around me, asking me what the birds that flew over us were saying, or the goats across the street, or the trees in the playground. I would respond, and they would marvel at my answers even though they really didn’t believe me. But when the headmistress summoned my parents and me to her office one day and explained to them that I was becoming a distraction to the other kids, I had to stop talking about the sounds I heard.

Though I stopped talking about it at school and left it only to my parents at home, I was still very popular. My classmates always wanted to play with me, even when there were no stories about animals or trees talking. I had no idea why but I was open to playing with them as long as they allowed me to lead the way. I didn’t like them expressing their fear when I suggested we do something daring, like climbing a tree and doing somersaults from the branches onto the ground. This is because if someone expressed fear, somehow I would begin to feel that fear and would end up not doing what I wanted to do. So I just went ahead and did what I wanted, and, usually, the others would join in, or they would step aside and watch. I was like a superhero. All I needed was a cape or a bodysuit.

Life was beautiful. It was fun when I was the only child and a different kind of fun when my younger sister was born. I used my fierce imagination to explore everywhere I found myself. The schoolyard became a forest where I was a hunter, the backyard at home became an ocean in which I was a pirate sailing on a large ship, and the car that dropped me off at school and picked me up again became an armoured tank at war. But all of these were regularly disrupted because my mum and my sister were both born with a dangerous illness.

It attacked my mum frequently, and when it did, the house became silent—either because my dad had rushed her to the hospital, or because she was lying in her bed and moaning in pain.

I would stay in my room and cry when she cried because I knew I couldn’t stop the pain and it made me realise how powerless I was: a superhero without any powers.

My sister didn’t suffer as much as my mother. One night, as we sat around the dining table and ate fried plantains and eggs, my dad told us of a doctor friend of his who had told him of another doctor in London who could cure my sister of her illness.

I had asked if the doctor could heal my mum too, and my dad had said that he hoped that would happen, but first, the doctor had to see my sister because she was younger and the treatment worked better on younger people.

I looked at my mum listening to my dad as he spoke and I wasn’t sure at first if she was happy or sad, so I opened my mouth to ask her—but my dog, Kompa, brushed against my leg.

And when I looked down at him, he said, while shaking his head, “Mum is not sad, she is happy that one of them will get well, so don’t open your big mouth to ask her if she is sad.”

So I closed my big mouth and listened to Dad tell us all about the trip he had to take to London with my sister.

I listened to them talk about the chances of the illness being treated and how cold London was and how far it is from Lagos, where we lived. As I sat there listening, I began to imagine myself as an eagle flying free across the ocean towards the city they described as beautiful, clean, and filled with miraculous healing.

2

The Night My Mother Slept

The night my mum slept and didn’t wake up, my dad and my younger sister had travelled to the cold, faraway city of London.

I was alone with her that night, and I remember all she told me in her weak voice as she lay on her large, queen-size bed.

My mum cried and screamed a lot, not just that night, but on a lot of the other days when she suffered her crisis. It lasted a couple of hours sometimes and other times a couple of days. Once, it lasted for months. Sometimes, during the crisis, she would be rushed to the hospital and admitted; other times she stayed at home and cried out in pain as my dad looked after her and my sister and I watched in concern.

That night my mum didn’t speak to me about the concept of sleeping and not waking up any more. The same thing she had called dying or death. I didn’t ask any more questions either because I didn’t know she would sleep and not wake up until she slept and didn’t wake up. Yet when I think back to that night, I realise that there was a way she looked down at me as she stroked my dark curly hair that showed that she actually knew that she would sleep and not wake up. It was an I-will-miss-you-so-much look. The kind of look you give someone you love who is leaving for a long time and you don’t know when you will see them again; or the kind of look that you give the last piece of a bar of delicious chocolate you have been eating, because you know that once you eat it, there will be no more of the chocolate left for you to eat.

There was a deep sadness in my mum’s eyes when she stared at me with that look. It was a long look and tears were rolling down her cheeks before she said to me in her weak voice, “Promise me you will look after your sister and your father.”

I promised because I thought that if I said I would, my mum would get better and go back to her normal happy, always-smiling-and-singing self.

“I will, Mum.”

“Kompa will take care of you,” she continued.

Kompa’s head shot up, and he stared at us from the foot of the bed.

“I will take care of him,” I countered in my big-brother voice.

She laughed and then winced audibly before she coughed and coughed and coughed while covering her mouth with her right hand and stroking my hair with her left.

Kompa looked at her in concern.

When she stopped coughing, she said, “You will take care of each other.”

Kompa barked once. It was his way of saying yes to people like my mum who couldn’t hear him speak, but to me he said, “It’s high time you agreed that it’s me who takes care of you and not you of me. But since Mum is ill, let’s agree with what she says so she can get well—we will take care of each other.”

“You wish,” I said to Kompa. Then I turned to my mum and continued, “Won’t you take care of all of us like you always have?”

She looked down at me as she stroked my hair and responded, “I will.”

“Thank you.”

I was eight years old small, my sister was five years old tiny, my mum was thirty years old frail, my dad was thirty-three years old strong, and the Border collie, Kompa, who my mother had given me for my seventh birthday, was a year and three months old feisty.

The bed in which my mother and I lay had big comfy pillows in white pillowcases that matched the white bed sheet and duvet. She cradled me in her thin arms and I felt her shiver. When I looked up at her, her tired eyes, which had dark circles around them, appeared to be sinking into her head. Her eyes were open very wide, and I stared at them for a while until they finally closed.

Unlike other times when she would simply smile when I asked her to tell me why she fell ill so often, my mum spoke more about the nature of her illness to me that night.

It was an illness that she had been born with and from which she was always falling sick.

Her illness was called sickle cell anaemia.

It happens to people who have something wrong with the red blood cells in their body.

She said, with a tinge of sadness, as though thinking about her illness was a heavy burden, “A cell is the smallest part of our bodies.”

“How small?” I asked.

“So small that it can only be seen under a microscope.”

“What does it look like?”

“It’s like a workshop.”

“A workshop?”

“Yes, complete with benches and machines. But they’re not really benches and machines like you have seen, but things that look like them even though they’re all parts of the cell.”

“Hmmm.” This was the only sound I made as I tried to understand what she meant.

She continued, “Can you imagine it?”

“No.”

She laughed. It was short, and it winded her. She stopped for a while to gather her breath, and then she continued.

“Think of your body as the kitchen in this house. And we are getting ready for a party, so I have all my friends come over to help me cook. All of us doing one thing or the other to prepare the food. Some cutting vegetables, some washing rice, some preparing meat, others kneading the dough, everyone working to get food ready for the party. The food for the party is made up of different meals and the tasks everyone is performing are what make the different meals. Those tasks are different, and some of them, even though they are different, are still needed to make the same meal. For example, the meat that is washed and boiled is used for the stews, the soups and the meat pies. The person making the meat is focused on it even though the meat will be used for different meals which are being prepared by different people. So, what the person is doing in the kitchen is like what the cell is doing in your body. You see it now?”

“Yes.” I could see it clearly.

“Great. All that happens in a cell is very specialised. So, it does one thing and one thing only.”

“All the cells in our body do only one thing?”

“No, not all cells. Each cell does one thing. All the cells that do the same thing exist together in groups. That is why there are different groups of cells that do different kinds of things. And because they all do different things, they all work collectively, like in teams, and are able to make our bodies function.”

“Oh, I get it now,” I said, my interest piqued.

I imagined the cells like a football team: a goalkeeper, defenders, midfielders and strikers. I could even see substitutes on the bench and trainers and a coach.

My mum continued, “Each group of cells does its job so that other groups of cells can do their jobs. When one group has a problem doing its job, other groups begin to fail in doing their jobs too. The more they fail, the more our bodies begin to fall sick, and if we cannot stop the cells from failing to do their jobs, our bodies will fall sick so often that, one day, we will close our eyes in the forever sleep.”

“Forever sleep?” I asked.

“Yes, like death.”

“We die if our cells stop doing their jobs?”

“Yes, we do. Especially our white blood cells.”

“White like white in colour?”

“Yes. They are white like a watery milky colour.”

“What do they do?”

“They fight any disease in our body. They protect us.”

“Like soldiers?”

“Perfect description.”

“Wow!” I said as I imagined soldiers in white running all around my body fighting colds, and fevers, and runny noses, and headaches.

Then I looked up at my mum and asked, “Do they have guns?”

“Not like the kind of guns you see on TV or your toy guns, but there are special weapons they have which they fight with, and once they have them, they are called a different name.”

“Different from white blood cells?”

“Yes, just in name only, but they are still white blood cells.”

“What is the name?”

“It is too advanced for you, love—when you grow older you will learn all about it in school.”

“I want to know now, Mum. What are they called?”

She shook her head in an exhausted way.

“Please, Mum,” I said with my puppy face.

She laughed.

“Okay, they are called lymphocytes.”

“Lymphocytes,” I repeated in wonder.

“Yes.”

“Can you spell it?”

“L – Y – M – P – H – O – C – Y – T – E – S.” She spelt it, and I repeated it along with her. It was one of the most difficult words I had heard, although it was not as difficult as the words “encyclopaedia”, “penicillin”, “regurgitate”, “photosynthesis”, “parliamentary”, “democratic” or “metamorphosis”. But unlike the others, it created pictures for me. Fun pictures that moved as though across a television screen.

“Lymphocytes are so cool. Are there, like, black blood cells too?”

She laughed even louder. Then she coughed a bit and fell silent, trying to catch her breath. Kompa wagged his tail twice, made a whining sound and fell silent too. Then my mum began to speak again.

“There are no black blood cells, just red blood cells.”

“Red blood cells?”

“Yes, they are called red because they are actually red in colour.”

“Why are they red?”

“They are red because they have something that helps them carry oxygen.”

“What is it called?”

“Too many questions. You don’t need to know all of these details now.”

“But I want to, please. Remember you said I need to know at least one new word per day.”

“Yes, but not these words. These are scientific words.”

“I like science.”

“Do you ever give up, young man?”

“No,” I said with pride.

“Okay. It’s called haemoglobin.”

“Haemoglobin,” I repeated with added wonder, and then I continued, “Can you spell it?”

“Not this time. You try to spell it.”

“I can’t.”

“Yes, you can.”

I hesitated for a moment. She caressed my hair as she looked down at me from the slightly raised pillow where her head lay.

“H – A – I – R – M – O – R…” I began to spell it and trailed off when she began to giggle.

“I told you I couldn’t spell it,” I giggled too.

“Bless you, love. At least you tried. Be proud of yourself.”

“Spell it for me, Mum,” I continued impatiently.

“You say thank you first.” It was stern.

“Thank you.” I lowered my voice.

“Good. Okay, it is spelt like this: H – A – E – M – O – G – L – O – B – I – N.” She spelt it out and I spelt it alongside her.

I repeated the word again and again. It wasn’t as intriguing as “lymphocytes” and didn’t create any pictures in my mind, but I still liked the sound of it. I quickly shelved it on my word board—that shelf in my mind where I kept all the new words I learnt. Then I continued asking questions.

“So if white blood cells are soldiers, what are red blood cells?”

My mum lifted herself a little higher on the bed so that some of her upper back lay on the pillow, then she began to answer.

“Red…”

Then she stopped with a gasp.

And she began to pant as she squeezed her face and balled her hand, which was on my head, into a fist before she stretched out her body and raised her torso slightly from the bed. I felt it tremble beside me as a groan escaped from her lips.

I sat up and looked at her.

Kompa also sat up on his haunches and stared at her, quietly.

She began vibrating on the bed, as her face squeezed even more and her hands gripped the duvet that covered the lower part of her body.

It went on for a short while and she swayed from left to right as the pain coursed through her body.

I didn’t know what to say, but I felt so sad that she was suffering.

Kompa placed one paw on her foot and kept staring at her, and it was as though that action did the trick.

My mum collapsed on the bed and began gasping. Her forehead was covered with sweat, and she let out the words “Sweet Lord!”

She continued breathing with loud exhalations of air until she was calm and smiling. Then she patted her abdomen and spoke.

“Come lie down. Mummy is just going through a rough patch.”

I lay down in the same position I was in before.

Kompa did the same.

My mum continued, “So you were asking me about red blood cells?”

“Yes, Mum. But you don’t have to tell me if you are still in pain.”

“It’s okay, the pain is gone.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, love. Thank you for asking though.”

I smiled.

She caressed my hair and began speaking with a weaker voice.

“Red blood cells are the cells that help carry oxygen around the body. They help us breathe. They are round in shape and flexible, and this allows them to move easily around our body through our blood vessels.”

“Are blood vessels like tunnels that our blood flows through?”

“Yes,” she answered, smiling.

“Like covered drains or gutters?”

“Exactly. But for people like me who have sickle cell anaemia, the red blood cells are not flexible but rigid, and they are shaped like sickles or the crescent moons that hang high in the sky. Because of this, they get stuck in the small blood vessels in our body, which slows down or blocks the blood flow, which in turn reduces the amount of oxygen our body gets.”

“How are my red blood cells?”

“They are perfectly round, and they flow freely through your blood vessels.”

“And yours are curved like sickles or a comma and get hooked, so they block your blood vessels.” I was repeating it to myself to make sure I fully understood it.

“Yes. But blocking the blood vessels and reducing the oxygen is not the only problem—there is also the incredible pain that comes with it. You have seen me feel the pain before, right?”

I nodded.

My mum continued, “It’s a horrible kind of pain that spreads all over your body, particularly your joints, your spleen and even all of your bones and makes you scream out in anguish. That is what I mean when I say I am in crisis. You remember me talking about a crisis?”

“Yes, I remember that,” I said, then I continued, eager to show that I had listened to the little bits of information she had given me over time, “A crisis is the period in which the sickle cell anaemia flares up, the pain rises, and you scream.”

She laughed. It was weak, but her eyes twinkled through the mistiness that had gathered in them. I could feel the pride in them. And the deep love. She stroked my head and said, “Sorry for screaming.”

“Don’t be sorry, Mum. I wish I could do something to stop your pain.”

“Let’s both pray that the pain goes away?”

I nodded eagerly.

And my mum began to pray.

Then she stopped and began to pant. Her breathing was fast, and her hands stopped stroking my hair. Her body shook slowly at first and then even more vigorously.

I sat up and looked down at her.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)