Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

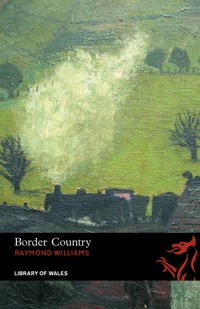

Harry Price has worked for years as a railway signalman in the Welsh border village of Glynmawr. Now he has had a stroke, and his son, Matthew, a lecturer at Oxford, returns to the close-knit community that he left. As Harry lies in silent pain in his cramped bedroom, Matthew experiences the jarring familiarity of the childhood world which, alienated, he can no longer re-enter. Struggling with the unspoken tensions and losses that returning home has provoked, he recalls what has made him who he is. Upstairs his deeply thoughtful father recalls his own arrival in the village, the relationships between men during the General Strike, and the social and personal changes that followed, and he struggles to articulate all that has been left unsaid. A beautiful and moving portrait of the love between a father and son, and of the strength and resilience of a small community, Border Country is Raymond Williams finest novel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 565

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

About Raymond Williams

Foreword

Part One

Pt 1 Chapter One

Pt 1 Chapter Two

Pt 1 Chapter Three

Pt 1 Chapter Four

Pt 1 Chapter Five

Pt 1 Chapter Six

Pt 1 Chapter Seven

Pt 1 Chapter Eight

Pt 1 Chapter Nine

Pt 1 Chapter Ten

Part Two

Pt 2 Chapter One

Pt 2 Chapter Two

Pt 2 Chapter Three

Foreword and Cover image by

Library of Wales

Copyright

Border Country

Raymond Williams

LIBRARY OF WALES

Raymond Williams was born in the Welsh border village of Pandyin 1921. He was educated at Abergavenny Grammar School and at Trinity College, Cambridge and he served in the Second World War as a Captain in the 21st Anti-Tank Regiment, Royal Artillery. After the war he began an influential career in education with the Extra Mural Department at Oxford University. His life-long concern with the interface between social development and cultural process marked him out as one of the most perceptive and influential intellectual figures of his generation.

He returned to Cambridge as a Lecturer in 1961 and was appointed its first Professor of Drama in 1974. His best-known publications includeCulture and Society(1958),The Long Revolution(1961),The Country and the City(1973),Keywords(1976) andMarxism and Literature(1977).

Raymond Williams was an acclaimed cultural critic and commentator but he considered all of his writing, including fiction, to be connected.Border Country(1960) was the first of a trilogy of novels with a predominantly Welsh theme or setting, and his engagement with Wales continued in the political thrillerThe Volunteers(1978),Loyalties(1985) and the massive two-volumePeople of the Black Mountains(1988-90). He died in 1988.

Foreword

I first readBorder Countrywhen it appeared as a Penguin paperback in 1964. Its author was familiar to me for his pathbreaking critical studiesCulture and Society(1958) andThe Long Revolution(1961), but an undergraduate from the Rhondda at Oxford did not buy hardback novels, and I had only been made aware of the existence of Raymond Williams’ 1960 novel from biographical blurbs. I shelled out my five shillings and took it home. For me it crackled with the excitement of a discovery I had somehow known all along. I did not stop reading until, some time the next day, it was finished, and I have never stopped re-reading that original copy since. The hook for me was the instantly recognisable emotional and intellectual journey of a working-class boy who goes away from his shaping community. By the 1960s this had become a familiar pattern, one to be repeated for generations, but it was an experience originating directly, as occurred in Raymond Williams’ own life, from that first limited grammar-school exodus of the 1930s. This is still usually told as a story about successful individuals gratefully climbing ladders. Not so here – instead, with a subtlety of touch matched by an integrity of vision, the novel does what no history fully can do and little fiction has achieved: it shows the inescapable intertwining of individuals’ lives and social conditions in the fluidity of lived experience that we all share. Although you can approachBorder Countryin more than one way, the final route out will always be the same, for, as Matthew Price reflects at the end of the book’s odyssey: ‘The distance is measured, and that is what matters. By measuring the distance, we come home.’

Border Countryis a deceptive novel. It grips us immediately with its story of one man running and never stopping, but from the first page it also asks the reader to think deeply about how we conceive our general history as a society. The style ofBorder Countryis pared down, almost entirely pruned of similes and metaphors, and quietly serves its straightforward tale, but the novel is also clearly and defiantly proud to be so plain. It is patently a novel about Welsh people set in Wales, and it deals centrally with the myth and reality of the 1926 General Strike, as it was felt through Welsh history and in individual lives. Yet it is geographically marginal to those thunderous struggles in the coalfield, and its Welsh character is more locally rooted than nationally defined. On publication in 1960, this novel, which had been worked on since the late 1940s and was completed in 1958, seemed to some to be, in its dogged realism, past its time, but in its global relevance today it is more contemporary than ever.

The novel is set in motion, from its very first sentence, with Matthew Price running for a bus in London. He is a university lecturer who is working on population movements in the industrialising valleys of South Wales in the nineteenth century. He is dissatisfied with the scholarly techniques he has learned to measure this human displacement and renewed settlement. The results have ‘the solidity and precision of ice cubes, while a given temperature is maintained.’ In actual life no such precision is possible. So what exactly is being measured? It is the overall picture, without which no change can be measured, but after which the real nature of existence has been lost: ‘The man on the bus, the man in the street, but I am Price from Glynmawr,’ Matthew muses to himself.

Raymond Williams from Pandy spent his lifetime working out how not to betray that individual essence whilst at the same time understanding its wider and connected cultural being. I believe he showed the way best in his fiction, where the journey is undertaken not in order to go back – for that is never possible – but in order to see how social renewal can occur as growth in human terms.Border Countryis, therefore, concerned with both Space and Time as the twinned defining attributes of human communities.

The time-shifts move us from Matthew’s return – by train and car – to be with his dying father, Harry Price, railway signalman, to Harry’s own coming to Glynmawr with his young bride, Ellen, to work in the 1920s. It is the General Strike of 1926 that brings one form of self-definition to a head. In a number of brilliantly poised passages of dialogue, Raymond Williams takes his variously committed railway workers through the gradations of political commitment and self-sacrifice which weighted their act of solidarity with the locked-out miners with such profound social significance. Its meaning resonated as late as 1984, when the last industrial reference back to 1926 was made. And possibly, if we understand such support in terms of irreducible human values rather than political flotsam, it retains such meaning even beyond its particular time. Certainly that is how Williams would have us see it. His insistence is that it is only by contemplating how individual destiny interplays with wider forces, always experienced spatially, that we can makes sense of life in the human chronology of Price from Glynmawr. The alternative, and profoundly so, is submission to non-sense.

The novel’s most plangent tone is, in counterpoint then, a lyrical one. ‘I know this country,’ the writer informs us in the prefatory note to its first printing and we can easily see that he loved it too. Not as a landscape for tourist consumption but as a land made over and over, often with intense struggle betweensocial classes as much as against nature, to create human habitationfit for the potential of always changing communities:

Once they were up on the road, Harry and Ellen could look out over the valley and the village in which they had come to live…

The narrow road wound through the valley. The railway, leaving the cutting at the station, ran out north on an embankment, roughly parallel with the road but a quarter of a mile distant. Between road and railway, in its curving course, ran the Honddu, the black water. On the east of the road ran the grassed embankment of the old tramroad, with a few overgrown stone quarries near its line. The directions coincided, and Harry, as he walked, seemed to relax and settle. Walking the road in the October evening, they felt on their faces their own country: the huddled farmhouses, with their dirty yards; the dogs under the weed-growing walls; the cattle-marked crossing from the sloping field under the orchard; the long fields, in the line of the valley, where the cattle pastured; the turned red earth of the small, thickly-hedged ploughland; the brooks, alder-lined, curving and meeting; the bracken-heaped tussocky fields up the mountain, where the sheep were scattered under the wood-shaded barns; the occasional white wall, direct towards the sun, standing out where its windows caught the light across the valley; the high black line of the mountains, and the ring of the sheep wall.

The patch of eight houses lay ahead: set so that looking to the north and west the spurs of the mountains lay open in the distance. Harry stopped, put down the leather box, and looked around.‘All right, last bit,’ he said after resting, and they went on to the houses.

Within its frame, then, of Time and Space, we share in and comprehend human endeavour and human growth and human loss. There is not a false or sentimental note anywhere in this book. Nothing is romanticised and nobody is idealised. We are never allowed to see what is local in action as being somehow limited in reach or implication. Raymond Williams fully understood that his country on the border was only different in its specific shapes, so that at someone else’s border, in the changing particularities of other histories of migration and settlement and struggle, the narrative, personal and general, continued.

I believe thatBorder Countryis one of the most moving andaccomplished novels of the twentieth century, written anywhere by anyone. In Wales, the fact that it was written by Williams from Pandy is an occasion for small, extra celebration. More importantly, in its new Library ofWales format, it deserves to go out more widely than ever into the world, so that by being measured it can properly come home to us again.

Dai Smith

PartOne

Chapter One

1

As he ran for the bus he was glad: not only because he was going home, after a difficult day, but mainly because the run in itself was pleasant, as a break from the contained indifference that was still his dominant feeling of London. The conductress, a West Indian, smiled as he jumped to the platform, and he said, ‘Good evening,’ and was answered, with an easiness that had almost been lost. You don’t speak to people in London, he remembered; in fact you don’t speak to people anywhere in England; there is plenty of time for that sort of thing on the appointed occasions – in an office, in a seminar, at a party. He went upstairs, still half smiling, and was glad there had been no time to buy an evening paper; there was plenty to look at, in the bus and in the streets.

Matthew Price had been eight years a university lecturer, in economic history. He knew of nothing he more wanted to be, though his anxiety about his work had become marked.He was generally considered a good lecturer, but his research, which had started so well, had made little real progress over the last three years. It might be simply the usual fading, which he had watched in others, but it presented itself differently to his own mind. It is a problem of measurement, of the means of measurement, he had come to tell himself. But the reality which this phrase offered to interpret was, he could see, more disturbing. He was working on population movements into the Welsh mining valleys in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. But I have moved myself, he objected, and what is it really that I must measure? The techniques I have learned have the solidity and precision of ice-cubes, while a given temperature is maintained. But it is a temperature I can’t really maintain; the door of the box keeps flying open. It’s hardly a population movement from Glynmawr to London, but it’s a change of substance, as it must also have been for them, when they left their villages. And the ways of measuring this are not only outside my discipline. They are somewhere else altogether, that I can feel but not handle, touch but not grasp. To the nearest hundred, or to any usable percentage, my single figure is indifferent, but it is not only a relevant figure: without it, the change can’t be measured at all. The man on the bus, the man in the street, but I am Price from Glynmawr, and here, understandably, that means very little. You get it through Gwenton. Yes, they say the gateway of Wales. Yes, border country.

It was a long bus-ride out, and it was dark when he got off: town dark. The lamps had been lit among the bare trees, and shone down into the little front gardens. There were trees and gardens all along this street. When, soon after their marriage, Matthew and Susan had seen this street, they had felt they could settle in it. It was suburban, whatever that might mean, but this was little enough to pay for trees and a garden. Theirs was the end house: grey, single-fronted, with a wide bay window. At the gate stood a laburnum, as he had learned to call it except when it was in flower, when it was a golden chain again. On the gate had been a panel announcing ‘Laburnum House’, but this had been burned. Collecting the names of houses had been one of their earliest pastimes, before they married. Susan, the daughter of a Cumberland teacher, had been one of Matthew’s first students. They had married two months after her graduation. While she was still his student, they had walked, endlessly, around a London still strange to them both. Their direction, always, was from a large street into a smaller, until they were virtually lost and had to ask their way back. They had found this street on one of these walks, and since they had settled in it a new line of shops and a new junior school had been built nearby. Their two boys had been born and would grow up here, and would think of it as home.

As Matthew pushed open the door, there was a shouted protest. Harry, just inside the door, was jumping to tap back a limp red balloon, which had to float between the door and the stairs as goals. He missed it as the door opened suddenly, and the balloon floated down under Matthew’s feet.

‘Anyway, that’s not a goal, that’s interference,’ Harry shouted.

‘You were missing it, anyway,’ Jack shouted back furiously, his hair loose over his eyes.

‘Half-time,’ Matthew said, punting the balloon away and closing the door.‘Anyway, where’s Susan?’

‘Getting tea. Anyway it’s no good, all its wind’s going.’

Matthew walked through to the kitchen, first stumbling on a heap of marbles and cursing. Susan opened the kitchen door and there was a further scuffle as Rex, the collie pup from Glynmawr, tore out and jumped up at Matthew. The telephone rang.

‘Not again,’ Matthew said. ‘They time the bastard for when I get home.’

‘Say no anyway. We don’t want a drink with anybody, we don’t want coffee, we can cook our own supper.’

‘They can’t hear you, Susan. And I’m not answering it.’

‘All right.’

He took off his coat in the kitchen, and closed the door, but the ringing went on.

‘Are you sure it’s not work?’

‘That would be important, of course. Some tidy little committee.’

‘It sounds as if they’re serious,’ Susan said, as the ringing continued.

‘These social types always are.’

They looked at each other, anxiously, seeking reassurance.The boys opened the door and Jack asked,‘Are you ever going to answer that thing?’

‘All right,’ Matthew said, and went quickly out. He picked up the receiver and said, impatiently, ‘Price.’ Susan had followed him, and was watching his face as he listened. There was a sudden tightening to attention, and he glanced up at her.

‘Yes who is that exactly?... I see... When?... Yes... Yes, thank you.’ He was pushing the receiver tightly into his face, as if he could not understand what was being said. When the call ended, he got up and stared at Susan, saying nothing. She watched him, intently, while the boys shouted as they ran past.

‘Tell me, love.’

‘My father.’

‘An accident?’

‘No, some kind of stroke. It was a bad line. They can talk endlessly but they couldn’t make it clear.’

‘They want you to come?’

‘Yes.’

‘Could you get through tonight?’

‘I don’t know. I simply don’t know.’

‘I’ll pack your things. You ring inquiries. You must get as far as you can.’

Matthew nodded, but moved away from the phone. The dog was barking as the boys played with it in the passage.

‘All right,’ Matthew said, standing quite still.

‘Ring inquiries,’ Susan said, facing him.

‘All right.’

They looked at each other for a moment, as the boys and the dog rushed past them; then each turned to what had to be done.

‘He’s a proper collie,’ Jack shouted, ‘only of course he’s got to be trained.’

‘We know that,’ Harry said.

2

Abruptly the rhythm changed, as the wheels crossed the bridge. Matthew got up, and took his case from the rack. As he steadied the case, he looked at the rail-map, with its familiar network of arteries, held in the shape of Wales, and to the east the lines running out and elongating, into England. The shape of Wales: pig-headed Wales you say to remember to draw it. And no returns.

The usual photographs were at the sides of the map. On the far side was the abbey, that he had always known: the ruined abbey at Trawsfynydd that had not changed in his lifetime. On the near side was the front at Tenby. A railing horizon, in the wide paleness of sky and sea; then, making the picture, two girls smiling under cloche hats, and an Austin drawn up beyond them, the nose of its radiator in the air. Like the compartment, the photographswere more than thirty years old: nearly his own age.Damp had got in at the corners, irregularly staining the prints.

The wheels slowed, and the train passed under the gaunt footbridge and drew up at the platform, past the line of yellow lamps. A scurry of rain hit the misted glass. He jerked at the window strap, and reached out to open the door. No one else got out. He stood alone on the dark platform, looking around. Starting as late as he had, there had been no useful stop after Gwenton; he would have to walk the five miles north to Glynmawr.

The light rain swept his face, and he moved away, quickly, under the wooden awning of the station building, glancing up at the fretwork pattern of its edge. The engine whistled. The guard was already back in his window. As the train pulled out, for its next thirty miles, Matthew turned up his collar and re-lit his pipe. He waved, briefly, to the guard as he passed.

Down first into the town: that was half a mile of the walk. For here was the station, by the asylum: both on the outskirts, where the Victorians thought they belonged. The wind was blowing from the dark wall of the mountains, rattling a hanging sign.

As he walked to the gate, a porter came out of the lamp-room, and held out his hand. Matthew gave him his ticket, looking past him at the gaslight of the lamp-room,and the red wall of its fire. He smiled, and the porter lookedat him strangely. Then they separated, Matthew returning the good night. You come as a stranger: accept that.

As he walked down the station approach, a car drove towards him, raking him with its headlights, in which the rain drifted. The driver blew his horn, but Matthew ignored it. He walked on, steadily, turning his face from the wind. So much of the memory of this country was a memory of walking: walking alone, with the wind ripping at him; alone it seemed always, in memory, though not in fact. The car was turning behind him, but he took no notice. Then farther down it overtook him, and drew in close to the pavement.

‘Where you off to then?’ a voice called from the car.

‘Glynmawr,’ he answered, abruptly.

‘Glynmawr? Where’s that then?’

‘About five miles north.’

As soon as he had answered, he walked on. He was set, now, on the walk. He wanted to come back like this: slowly, with obvious difficulty, making up his own mind.

‘You’ll get wet, you know, Will,’ the voice said suddenly. Matthew stopped, and swung round, arrested by the name.Always, when he had lived here, he had been Will, though his registered name was Matthew, and he had used this invariably since he had gone away.

‘I’m sorry. Who is that?’ he asked, walking back to the car.

‘Come on, mun, get in.’

‘Oh, I see,’ Matthew said, and walked round through the headlights and opened the door. Morgan Rosser sat behind the wheel, heavily coated, his bare grey head stiff and poised, looking forward.

‘I’m sorry,’ Matthew said. ‘I should have recognized your voice. Only sometimes we only recognize when we’re expecting it.’

‘You thought we’d leave you to walk then?’ Morgan said, looking across at him.

‘I expected to walk. Nobody knew the time of my train.’

‘I’ve got timetables. Get in, Will. Don’t stand in the wet.’

Matthew hesitated, and got into the car. Morgan leaned across him, heavily, and pulled the door shut.

‘Your Mam rung me,’ he said, settling again in his seat. ‘She said Mrs Hybart rung you a quarter past five, you said you’d get the first train.’

‘Well, thank you, anyway. I didn’t expect it.’

Morgan did not answer, but with a hard movement sent the car forward. Matthew jerked back, then steadied himself. It is like that, this country; it takes you over as soon as you set foot in it. Yet I was sent for to come at once.

Rain had made the glass in front of him opaque. He looked down, then across through the fan of the driver’s wiper. They turned out of the approach, then down the long road into the town. Nothing moved along it, except the bare trees in the wind. Again, in the town, the narrow main street was deserted, as they turned past the Town Hall to the market, and then up the long pitch to Glynmawr. He stared out at the empty town. It was years since he had sat beside Morgan Rosser in the car, along this same road. The last time had been before he first went away.

‘How are you then, Will?’

‘Not bad, thanks. And you?’

‘This is bad though.’

‘Yes.’

‘He’s been too good a man, Will.’

Matthew turned and looked at him. The good-looking face was set and calm, under the thick grey hair. The eyes looked forward, at the narrow road.

‘Maybe.’

‘It’s what we ought to have known, Will. The strength, yes, and that’s what he showed. But now this, always.’

‘We’ll see,’ Matthew said, and Morgan glanced at him, and then back at the road.

They sat in silence until they were into Glynmawr, with its intermittent groups of houses and the fields between them. In the headlights, along the road, every feature came up in its remembered place. By the school the road had been widened, and the corner was less dangerous. The headlights beamed along the banked hedges, and cut quick swathes through the gateways to the fields.

‘Anyway, it’s good to see you again, Will. Even if you did think we’d leave you to walk.’

‘Aye, only then after all you were late, see,’ Matthew said, quickly. He felt the older man stiffen, and then the relief. ‘Fifteen seconds, mun. At most. And then you come out of them gates with your head down, so I nearly run you over. Even then I had to stop and ask you the way to Glynmawr.’

‘Well I told you, accurate.’

‘Aye, near enough.’

‘And the rain, see. Wouldn’t you keep your head down?’

‘Aye, I suppose.’

It was easy at last, and enough had been re-established. They relaxed as the car slowed and the headlights shone back from the headstones at the first chapel, above the river. The car turned into the lane, and now the trees were arched overhead, and it was suddenly darker, the lights of the car isolated. Matthew stared out at the wet red earth of the banks, as the car rolled and slipped on the rutted pitch. Then the pitch flattened, the houses came up into view, and at once they were among them.

‘Should remember this house, anyhow,’ Morgan said, as he stopped the car.

‘You’re coming in?’

‘You go on, Will. I’ll come after. I’ve got you here.’

‘All right,’ Matthew said, and opened the gate to the house.

3

He walked round to go in by the back door. But the door was opened before he reached it, and his mother stood waiting just inside the kitchen. He leaned forward, and quickly kissed her cheek.

‘You got here then, Will.’

‘Yes, and the lift.’

‘I been listening for the car. I knew Morgan would do it. He’s very good.’

They moved together into the kitchen, and as Matthew put down his bag Morgan came in behind them, closing the door.

‘You’ll be hungry, Will.’

Matthew had turned away, and was taking off his coat. He hung it on the line of pegs beside the door, where the working coats hung. The pegs were laden, and he had to push at the other coats to hang up his own.

‘And you, Morgan, you’ll have something.’

‘No, no, girl, I haven’t come for a meal.’

‘It’s all ready, look.’

There was a dark home-cured ham on the table, and cut bread and butter and a bottle of wheat wine.

‘Only first...’ Matthew said, and hesitated, watching his mother’s face. It was too like an ordinary home-coming, with his father at work. It needed an effort to think of him lying upstairs.

‘Well, yes, you’ll want to see him. Only leave it a bit, Will. He’s sleeping heavy.’

Matthew looked past her, across the kitchen. As a rule they needed to put very little into words, but now with nothing said he felt himself hardening. Some things at least must take precedence.

‘Has there been any change?’

‘No, Will, I don’t think so. You’ll have to see. Look, sit down, the both of you. Sit down at the table.’

‘I won’t stay,’ Morgan said, but sat on the edge of the hard chair between the table and the sink. Matthew, still standing, felt suddenly awkward. He seemed too big to be standing there, close to his mother.

‘He’s sleeping, is he? Shall I go up and look?’

‘No, I’ll go up. In a minute. It’s the injection, Will, he’s very heavy.’

‘What injection?’

‘Morphia, isn’t it? The doctor’s been twice.’

‘What doctor?’

‘Evans, he’s a nice chap. He’s taken over from Powell.’

‘What did he say?’

‘He said coronary.’

‘Thrombosis,’ Morgan said. ‘It’s the blood to the heart.’

‘I want to know how it happened,’ Matthew said. His voice seemed loud and sharp in the hushed room.

‘Sit down and eat then,’ Ellen said.

‘Aye, come on, Will,’ Morgan said quickly. ‘Too good to go wasting.’

‘You have some then, Morgan,’ Ellen invited.

‘No, no, girl. She’ll be keeping mine for me at home.’

‘It’s cold, it’ll wait,’ Matthew said. ‘I’ll eat when I’ve seen him.’

He saw the others watching him, and sat in the arm-chair, away from the table. His mother stayed, standing in the centre of her kitchen.

‘Well? Tell me.’

Ellen moved to the table, and poured wine from the tall green bottle into the two glasses. She set one in front of Morgan, and handed the other to Matthew, who took it and put it straight down on the dresser.

‘You won’t have eaten since dinner, Will.’

‘It’s all right.’

‘Tell Will how it happened,’ Morgan said.

‘Yes, Will, I was going to say,’ Ellen apologized, turning to her son. Looking up at her, he saw the sudden pain in her face.

‘It was in the box. This morning, about ten past eight.’

He watched her, hearing in her voice that she had said this often already; that the account had already been given to several others.

‘But the first was last night, and he didn’t say.’

‘How?’

‘He was in the end garden. He had fifty savoys he wanted in before dark. He had the pain then, but he tried to finish the planting. Then it got worse, and he came back in here. It was just dusk, I hadn’t put on the light. He sat where you’re sitting, but he didn’t say. He told me today he was glad it was dark, so I couldn’t see his face.’

‘Yes.’

‘I could hear from his voice there was pain, though he hardly answered. He said leave the light off, the dark rested him. He sat there for more than an hour. I thought it was tired. Only after, when I touched his forehead, I felt the sweat. I put down my hand to his hand, and he was catching the chair.’

‘But then?’

‘You know what he is, Will. He said it was nothing. I said he was sweating. He said it was nothing and would go.’

‘An hour?’

‘I hadn’t touched him, Will. Not till then. And the worst was over. When I put on the light he got up.’

Matthew looked away, along the line of the dresser.

‘Did he look bad?’ Morgan asked.

‘Yes, Morgan, he was grey. He got up and walked straight up to bed, said he’d leave supper. We both went and lay down. I said must he go to work. He said yes, of course, there was nothing to prevent him. If I’d known, of course.’

‘You’re not to blame your Mam,’ Morgan said, sharply. ‘You come now, and she says herself if she’d known. I’ve argued with Harry since before you was born. There’s nothing anybody can do.’

Matthew hesitated, looking away from the dresser.

‘I know. I hadn’t thought of blaming.’

‘If he’d only have said,’ Ellen cried. ‘He told me today it was like a fist gripping him, gripping deep, he said, where he didn’t know that he was. But he sat in the dark. Then this morning he got up half-past five, and dressed in the dark. I said how was he and he said better, the pain had gone. I heard him go off on his bike. Then at quarter to nine he was back here.’

‘Who brought him?’

‘Well, Jones the stationmaster found him. He’d just cleared a train and he shouted across to Jones. When Jones got up there, he was lying on his back by the fire. Jones thought he’d gone.’

‘I see.’

‘He was grey then, grey like stone, and the sweat was terrible. Jones got a coat under his head and called down to Phillips the ganger. They thought perhaps call a doctor there, but Phillips said carry him home. Phillips and Elwyn got him out to Phillips’s car, and brought him.’

‘Elwyn?’

‘Yes. You remember Elwyn.’

‘Of course.’

‘If he’d not have gone,’ Ellen said. ‘I can see that now.’

‘But it’s no use thinking all that,’ Morgan said, sharply. He was still sitting on the edge of the hard chair between the table and the sink; filling the space in his heavy black overcoat; the face square and ruddy, under the thick curling grey hair.

‘It’s thinking from now,’ he said, still looking at Matthew.

‘Of course,’ Matthew agreed, and walked across the kitchento his overcoat. He took his pipe from a pocket, and with his knife began poking the dead ash into his palm. He still faced the coats, with their smell of work.

‘Will, you look now like Harry, standing there by the door,’ Morgan said. Matthew closed his knife, and blew down the empty pipe.

‘Do I?’

‘You get more like him,’ Ellen said. ‘Powell thought it was him the last time you was here, and he saw youacross the field.’

Matthew went to the fireplace, and threw down the ash in his hand.

‘Can I see him now, then?’

Ellen was standing very still, on the same spot. He could see more clearly now, in her face, the fear of the day. She had been colouring her hair, so that it was almost the yellow he remembered. The skin was pale, under the fine red lines on the cheeks. The eyes and the mouth seemed to have shrunk.

‘All right, I’ll go up first then.’

‘And I’ll get along,’ Morgan said. He stood as he spoke, and then lifted his glass and drank down the wine.

‘Thanks again for the lift, Morgan.’

‘I’ll be out again,’ Morgan said, moving to the door. Ellen hesitated, and smiled. As he closed the door, she walked down the passage to the stairs. Matthew followed her, a few steps behind, and stopped on the landing while she went into the bedroom. He heard her voice, very low, and a sudden deep voice, that he could not make into words. Ellen came out, and beckoned to him.

‘Only stay two or three minutes, Will,’ she whispered. He nodded, and walked quietly into the room.

4

The back bedroom, which Harry and Ellen always used, was small and crowded. There was only a narrow space to move round the bed to the single small window. The head of the bed was behind the opening door. Matthew stopped, in the warm drug-heavy air, and looked down.

The head on the pillow was much older than he had looked for: ten years older, at least, than when he had seen his father in the summer. The eyes were closed, in the flushed, drawn face.

‘Will.’

‘Yes.’

Harry opened his eyes and drew his right arm from under the covers. He leaned up a little from the pillow, and Matthew bent over him, taking the extended hand. The hand was pale, delicate, beautifully formed. The skin was very soft as he touched it, but the grip was hard.

‘This is no way, Will, to be welcoming you home.’

‘Well, I’m glad to come, and I know I’m welcome.’

‘Of course you are.’

The voice was deep and rough, very slow with effort. The effort merged, in the son’s mind, with memories of irritated correction. Always, in this voice, there was more than could easily be said, in any feeling.

‘Stay with me, Will. But I shan’t talk.’

‘I’ll stay.’

He moved and sat on the edge of the bed. As he looked down, at the hurt strength of the face, he seemed to feel the pressure on his own face, as if a cast were being taken. He could hardly breathe, while the long effort lasted, but then he turned, sharply, and looked away into the room.

The heavy mahogany wardrobe filled almost the whole space left by the bed. From the lampholder in front of it a length of flex drooped across the room to the headrail, where it was knotted and led into a switch. The flex was of two kinds, joined above the bed with what looked like the pink adhesive cover of a bandage. In the far corner of the room was a cupboarded water-tank, piped to the back- boiler in the room below.

He looked back at his father, who was not sleeping, but, with his eyes closed, fighting for strength. He knew that it was necessary to sit still and not talk, at the very moment when the pain and the danger were releasing feeling andconcentrating it, so that his whole mind seemed a longdialogue with his father – a dialogue of anxiety and allegiance, of deep separation and deep love. Nothing could stop this dialogue, nothing else seemed important, yet here, with the pale hand lying by his own hand, with the face no longer an image but there, anxiously watched, the command to silence was absolute, while the dialogue raced.

He turned away, and again looked round the room. On the walls hung pictures of his grandparents: placed, in each case, so that the eyes seemed to be watching the bed. The pictures were relatively unfamiliar, for he had rarely been in this room where his parents slept. The women he looked at quickly, in their high black dresses, with the brooches at their throats. Ellen’s mother, very like Ellen now, but easy and smiling, without strain. Harry’s mother – but there, for a moment, the heart stopped. The hard, strong, deeply-lined face; features coarse, almost animal in their rough casting; yet deeply composed, by the smiling mouth, into a gentleness that was part of the strength and the suffering. She had died too soon for Matthew to know her. She seemed, now, very far away.

The men were nearer, inevitably. Will Lewis, Ellen’s father, whom Matthew had never known though for years he had carried his name. A sharp, dark, inquisitive face, this hill-farmer turned miller; intelligent or cunning from alternative sides of the bargain. The eyes confident, extroverted without disturbance. Beside him, Jack Price, at sixty: the Jack Price his grandson remembered. Here again was complexity. The mediocre photograph had the life of a fine portrait. At first it was only his son’s head on the pillow, the strong, rough features partly hidden by the moustache and the line of beard fringing the jaw. Jack Price, labourer, very formal in the stiff, high collar and the smooth, unworn lapels and waistcoat. Then the eyes, colourless in the hazy enlargement, but not his son’s eyes, clouded, unfocused; eyes still with the devil in them, the spurt of feeling and gaiety. Remembering their living excitement, Matthew stared back, feeling their world. But the light in the bedroom was yellow and poor, and his own eyes watered with strain and had to be closed.

Silence settled in the crowded room, and then, across the valley, a train whistled. Harry looked up. Matthew turned at the movement but Harry was puzzled; he did not seem to know where he was. They could hear the train now, on the down line: a goods, labouring at the gradient. The heavy regular beat, beyond their range, seemed alone in the world in the silent valley.

‘I keep going off,’ Harry said. ‘But I listen for the trains.’

‘You need the sleep.’

‘I’m used to the trains, Will. Don’t worry.’

‘All right.’

‘How was your journey, Will?’

‘Very good. I was surprised really.’

Harry looked at the alarm clock on the mantelpiece. He stared at it for some time, as if disbelieving it.

‘That would be what then, the five-eight Paddington?’

‘Yes, I just caught it.’

‘It was awkward for you, Will. Having to leave your work.’

‘No, now, it’s all right.’

‘It was awkward,’ Harry repeated, and the voice, for a moment, held the remembered irritation and impatience. Matthew smiled, and saw the immediate response and lightening in the heavy eyes.

‘In any case,’ Harry said, looking away, ‘I want you to know I appreciate you coming. You’re a good son. I want you to realize...’

He stopped, and the colour rushed up into his face. Cold with alarm, Matthew leaned forward. His legs were stiff where they had been crossed as he sat on the bed. He felt the numbness as he moved, watching the eyes close.

‘It’s all right, it’s the pain again.’

‘Do you want anything?’

‘No. It’ll be...’

Matthew watched the effort in the face, and felt its counterpart in his own stiff tension, in the taut, anxious nerves round his mouth and eyes. There was a sound at the door, and Ellen came in.

‘Mam,’ Harry said, his voice very deep, hardly more than a breath.

‘Yes, it’s all right,’ Ellen said, and leaned over him. Matthew stood for a moment with his eyes closed, then walked out of the bedroom. As he walked downstairs to the kitchen, he felt the past moving with him: this life, this house, the trains through the valley.

Chapter Two

1

The four train ran north through the brakes and the green meadows under the Holy Mountain, and passed the up distant signal of Glynmawr. The worn black engine, with its nameClytha Courton the grimed, brass-lettered arc, laboured at the long bank. Above and behind it, its white plume flared and spread, then climbed and thinned until at a height the wind from the mountain plucked and scattered it into the grey felt overhang that, hiding the sun, moved slowly west to the farther mountains. On this October afternoon the train was late: four twenty-three at Glynmawr would be four twenty- seven, but by country time it would still be the four.

At the outer home signal, where the hedge was glatted to a worn path across the fields to the old road, the bank flattened, and the busy rhythm was broken. The four slackened and slowed to Glynmawr station, and drew down to stop with a heavy sigh of steam just short of the sleeper-paved crossing. The platforms at Glynmawr were not set opposite each other.

‘Why it was, see, they knew you was odd, and they built according.’

‘No, no, mun, it’s the lie of the ground.’

‘Or the boss of the railway was cross-eyed, they built this one in his honour.’

‘No, no, it’s the lie of the ground.’

To the up platform a zigzag path led down from the road and the bridge. At the bottom of the path the porter waited. Ted Wood from Aldgate had married and come back with a Welsh girl in service, but he couldn’t say where she came from; only the ‘more, more’ echoed along the carriages as they drew to a halt. Three children from the County School jumped from a compartment and raced around him and up a short cut to midway in the zigzag path, while he made no move but shouted that this would be the last time. One other door opened, and a young couple in their middle twenties got out. They put down their luggage, a suitcase and a leather box, and then the man got in again and brought out a corded wooden box and a paper parcel and a frail. The girl was anxious that he seemed to take so long, though he moved quickly, not even glancing along the platform. When he was out again, she closed the door but still he turned and tried the handle. Then he stood back and, glancing along the platform to the engine, gave the right away. The guard, farther back, had not yet appeared at his window.

TheClytha Courtwhistled, and spitting steam again drew slowly out. The porter, who had not yet moved, stared towards the guard’s window. He had taken out a large blue check handkerchief and was carefully blowing his nose. ‘Hoiup,’ came the shout suddenly, and the guard’s peaked, laughing face jumped into view. With a flick like a stone for ducks and drakes, he threw a heavy leather bag, and two large envelopes joined by a rubber band, straight at the porter’s chest. Wood could not get his hands down in time and the leather bag hit him as he held the big handkerchief. By the time Wood could shout, the guard was being carried away down the platform, past the standing couple and their luggage. He was head and shoulders at his window now, laughing and leaning out. He called to the couple as he went by:

‘Tell him stop blowing his nose on signal rags.’

‘What?’

‘Stop blowing his nose on signal rags.’

But the words were carried away on the wind, and the smoke came back now out of the cutting, and the carriages were curving away to the north. The words had been heard – it was not that – but this was not talk for an answer; the shout was enough.

The couple picked up their luggage, and walked along the platform.

‘You see that?’ Wood said, waiting for them. ‘Mad they all are down here like that, mad as hatters.’

‘Having a game on,’ the girl said, smiling.

‘Some flipping game. Throwing bags.’

‘He’s from Newport,’ the man said, but not as anexplanation.

‘Let him go back there,’ said the porter angrily, and winked. ‘I’ll have him.’

They stood together, and the porter looked at the luggage. The girl looked at her husband, waiting for him to speak.

‘Mr Rees about then?’

‘Stationmaster? You want him?’

‘I’m the new signalman.’

‘I thought perhaps you was.’

There was a pause, and the luggage was put down.

‘We got to find lodgings, we got nowhere fixed,’ the girl said anxiously.

Ted Wood took off his cap, and rubbed carefully at his fine, glossy hair. He was quite tall, and the pale face was bonily handsome. He looked at the girl, more frankly than she was used to. Her eyes were a very light blue; the long hair, escaping from the blue hat, was sandy yellow. Her husband stood very close to her, heavy in his black cap and long black overcoat. The face under the cap was very strong, with prominent cheekbones and a broad, heavy jaw. Under the big nose the mouth was wide, with ugly, irregular teeth. The solidity of the face and body made the extreme smallness of the hands and feet sudden and surprising. But the dominant impression was the curious stillness of the features, and the distance and withdrawal in the very deep blue eyes. He looked up now, slowly, and Wood turned with an easy excitement, as the stationmaster came towards them from his office under the bridge. Tom Rees was very tall, with thick egg-yellow over the brushed peak of his cap, his moustaches waxed to points that accentuated the long thinness of the face.

‘Here he is,’ Wood said.

‘Price? Mr Price?’

‘Aye. Mr Rees is it?’

‘Glad to meet you, my boy, certainly. And Mrs Price?’

‘How do you do, Mr Rees?’

‘They said your good man was married, when they sent me his bit of paper. If I’d known you were coming with him today...’

‘We’ve got to get lodgings. Harry should have written.’

‘Lodgings is no trouble. We’ll fix you up.’

‘Thank you.’

The stationmaster looked again at his new signalman.He had heard well of him, and the first impression was good,but there was something there that disturbed and slowed.

‘Now let’s see, what time’s it get dark?’ he said briskly, with a quick touch at the gummed pricks of his moustache. He was, after all, the stationmaster, and Price his new signalman and really no more than a lad. Decisions must be made, even against that withdrawn heaviness.

‘Six, half past.’

‘You’re on early turn in the morning, so this evening sometime you’ve got to be here, learn the box.’

‘I’m ready now.’

‘Aye, aye, of course, but the lodgings, boy, the lodgings, got to see to that before dark.’

‘Don’t worry, Harry, I can find it,’ the girl said quickly.

‘We’ll go up the box,’ Tom Rees said. ‘Only before we go...’ He looked back along the platform, making sure the four of them were alone. The porter, behind his back, winked at Price. ‘One of your mates, Harry,’ Tom Rees said, ‘Morgan Rosser, a young chap about your own age. Come from Pontypool, his father was a ticket collector.’

The girl looked along the platform and under the bridge to the box. Its bricks were grey, and its light-brown paint had begun to peel in the sun. She could see a figure standing there, near the barred window above the line. The sun broke through for a moment, and glinted along the rails, away south under the face and rockfall of the Holy Mountain and the copse of birches above the high, black siding.

‘It’s a tragic thing with Morgan Rosser,’ Tom Rees said. ‘His young wife, Mary, died the end of August, giving birth to his little girl.’

The girl nodded, but said nothing, staring at the black figure in the box.

‘He has a decent house, you see, down the far end,’ Tom Rees went on, ‘and he has an old woman, a housekeeper, and the little girl, nine weeks.’ Harry also was staring down the platform at the box, but his eyes were fixed and dark, as if staring anywhere.

‘It would be good for him and good for you,’ Tom Rees said, ‘if it was there you went to lodge.’

‘Shall I ask him?’ Harry said, roughly.

‘We’ll all three go up,’ Tom Rees said, frowning. ‘Only you see how it is. With it so recent.’

Ellen turned and looked at her husband. He met her eyes and at once looked away.

‘I’ll put the luggage in the office.’

‘Don’t worry about that, mate,’ Wood said quickly. ‘I shan’t pinch it.’

‘I’ll just put it in,’ Harry repeated, and gathered up the suitcase and the two boxes. He walked on down the platform and Ellen followed, beside the tall stationmaster. The porter took the frail from her, and walked a few paces behind. While Harry put the luggage in the office, Tom Rees and Ellen went up the steps to the box. They were opening the second of the two doors at the top as Harry followed them up. He had to wait as they moved in from the door. In the space between the doors was a low shelf, with three red fire buckets. One was filled with sand, one with clear water, and the one in the middle had blue soapy water in it, and a big piece of yellow soap and a little hand brush on the shelf beside it. Tom Rees moved, and Harry could see Morgan Rosser. He was smiling and shaking hands with Ellen.

‘Here he is then,’ Tom Rees said. ‘Harry Price, Morgan Rosser.’

Harry went up the step and across the box. They shook hands, and Morgan, though the smaller man, had the tighter grip. Tom Rees had prepared them for a man in mourning, but Morgan was easy, alert, confident. His face was small, with neat, regular features. The brown eyes were bright, the lips under the small black moustache full and red. The hair, a deep black, was tightly curled all over the crown, and came very low beside the small ears.

‘Glad to meet you, Harry. Of course I knew you were coming.’

‘Aye,’ Harry nodded, looking slowly around the box.

‘Now, Morgan, it’s like this,’ Tom Rees said formally. ‘Harry and his wife want lodgings. I wondered, as the first chance, whether they might come to you?’

‘Well,’ Morgan said, smiling and rubbing at his chin, ‘the rooms are there.’

‘Harry should have written before,’ Ellen said, anxiously. With the two new men she was trying very hard to be easy and sociable.

‘There’s me, my little daughter, and Mrs Lucas my housekeeper,’ Morgan said.‘And you can have the one front bedroom, and the room under it, and the meals Ma Lucas will see to.’

‘It sounds very nice,’ Ellen said. ‘Is it much?’

Morgan laughed. ‘Look, no secrets in public, my dear. I know your husband’s money, because it’s my money. You go and see if you like it. Harry and I’ll fix the rest.’

‘We’re very grateful,’ Ellen said, and smiled.

Morgan smiled back, and winked quite openly. Beside him, Harry was staring up at the yellowed diagram of the box’s signalling circuit. It had been hung so high on the wall that his head was sharply bent back.

‘Well, there you are you see, it’s all settled,’ Tom Rees said, looking happily around. ‘Now you and Harry get down and get your things in. Harry can come back about half past seven, all right?’

Harry nodded.

‘Far, is it?’

‘Two mile.’

‘Just under,’ Morgan said. ‘You just follow the road, Harry, past the school and to where the river comes alongside the road. There’s the Baptist chapel on your left and the Methodist the other side. Then up the lane see, beside the Methodist and there’s the whole patch. Mine’s the third on the right, the farthest.’

‘We’ll find it,’ Ellen said, pleased that everything was so easy. Harry looked away and spoke as he moved to the door.

‘Right, then. It’s all clear. Thank you.’

Ellen turned and followed him, taking leave of the others.

‘And Harry, get Ma Lucas to get a meal mind,’ Morgan called.

‘Thank you,’ Ellen said, and followed her husband down the steps. Ted Wood was standing by the door of the office, waiting for them.

‘Want a hand with it, Harry?’

‘No, no, I can manage. Two loads, I’m coming up again.’

He took up the suitcase and the leather box, and Ellen took the parcel and the frail.

‘Going to Rosser’s?’ Wood asked.

‘Yes,’ Ellen said.

‘He tell you how to get there?’

‘Oh, yes.’

‘That’s all right then. Wherever you go down this place, it’s the same. Cross the grass, past the muckheap, over two mountains, and it’s the sixth chapel on the left.’

‘Go on,’ Ellen laughed, ‘it’s not bad as that.’

‘You mark my words,’ Wood began, but Harry was already some way down the platform, and turning for the zigzag path. He looked round now, and Ellen, smilinggoodbye, hurried to follow him. Wood watched as they made their way up to the road: the girl’s bright hair and easy walk, the colour of her hat and coat, and beside her the stiff figure in black, his arms bent outwards with his load, his face set above the quick, steady walk.

‘That’s one way of running a railway,’ Wood said as they disappeared. He took out his big handkerchief, and folded it carefully before he lifted it to his face.

2

Once they were up on the road, Harry and Ellen could look out over the valley and the village in which they had come to live. To the east stood the Holy Mountain, the blue peak with the sudden rockfall on its western scarp. From the mountain to the north ran a ridge of high ground, and along it the grey Marcher castles. To the west, enclosing the valley, ran the Black Mountains: mile after mile of bracken and whin and heather, of black marsh and green springy turf, of rowan and stunted thorn and myrtle and bog-cotton, roamed by the mountain sheep and the wild ponies. Between the black ridges of Darren and Brynllwyd cut the narrow valley of Trawsfynydd, where the ruined abbey lay below the outcrop of rock marked by the great isolated boulder of the Kestrel. Fields climbed unevenly into the mountains, and far up on the black ridges stood isolated white farmhouses and grey barns.

Within its sheltering mountains, the Glynmawr valley lay broad and green. To a stranger Glynmawr would seem not a village, but just thinly populated farming country. Along the road where Harry and Ellen walked there were no lines of houses, no sudden centres of life. There were a few isolated houses by the roadside, and occasionally, under trees, a group or patch of five or six. Then lanes opened from the road, to east and west, making their way to other small groups, at varying distances. To the east, under the wooded ridge, lay Cefn, Penydre, Trefedw, Campstone. To the west, under the wall of the mountains, stood Glynnant, Cwmhonddu, The Pandy, The Bridge, Panteg. The village was the valley, the whole valley, these scattered groups brought together in a name.

To Harry and Ellen, this was not strange country. Harry had been born in Llangattock, only seven miles north-west, and Ellen in Peterstone, three miles farther north. A river runs between Llangattock and Peterstone, and that is the border with England. Across the river, in Peterstone, the folk speak with the slow, rich, Herefordshire tongue, that could still be heard in Ellen. On this side of the river is the quick Welsh accent, less sharp, less edged, than in the mining valleys which lie beyond the Black Mountains, to the south and west, but clear and distinct – a frontier crossed in the breath. In 1919, a year before coming to Glynmawr, Harry and Ellen had been married in Peterstone church. They had known each other as children, and were engaged when Harry came home from France with a bullet through his wrist. He had gone back, and later been gassed, so that one lung was permanently damaged and he could not smoke. After the wedding he had gone back to the railway, where before the war he had been a boy porter. He had become a porter-signalman and been moved from station to station in the mining valleys, Ellen moving with him in lodgings. Now, with the signalman’s job in Glynmawr, there was a chance to settle, to move nearer home. As they walked, carrying their things, they were facing the northern ridge beyond which their own villages lay.

The narrow road wound through the valley. The railway, leaving the cutting at the station, ran out north on an embankment, roughly parallel with the road but a quarter of a mile distant. Between road and railway, in its curving course, ran the Honddu, the black water. On the east of the road ran the grassed embankment of the old tramroad, with a few overgrown stone quarries near its line. The directions coincided, and Harry, as he walked, seemed to relax and settle. Walking the road in the October evening, they felt on their faces their own country: the huddled farmhouses, with their dirty yards; the dogs under the weed-growing walls; the cattle-marked crossing from the sloping field under the orchard; the long fields, in the line of the valley, where the cattle pastured; the turned red earth of the small, thickly-hedged ploughland; the brooks, alder-lined, curving and meeting; the bracken-heaped tussocky fields up the mountain, where the sheep were scattered under the wood-shaded barns; the occasional white wall, direct towards the sun, standing out where its windows caught the light across the valley; the high black line of the mountains, and the ring of the sheep-wall.

At the end, past the grey school and the master’s cottage, they could hear the river as it came towards the road, and soon they could see it, fast-flowing and stone-strewn below them, and there ahead was the first chapel, alder-shaded, and beyond it the other chapel, larger and better-built, its graveyard tidier. The lane ran up steeply from the road, and from its high banks the trees arched over. They turned up the lane and climbed steadily. Then round a long curve the pitch eased away, and the tree line opened. The patch of eight houses lay ahead: set so that looking to the north and west the spurs of the mountains lay open in the distance. Harry stopped, put down the leather box, and looked round.‘All right, last bit,’ he said after resting, and they walked on to the houses.