Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dedalus Original English Language Fiction

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

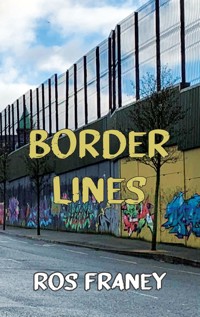

nionistsWhen a filmmaker and a British civil servant get caught up in the endgame of the Irish Troubles in 1997, they find themselves crossing borders that are ethical as well as physical and are forced to make lethal choices. Perdita Burn is a journalist with a track record in political documentary; Daniel Booth a British government press officer with a document to leak – a startling revelation about the Irish Troubles. A bomb explodes in South Armagh and Perdita is shocked to realise it was predicted in Daniel's document, suggesting collusion between some part of the security services and paramilitaries in Northern Ireland. Her attempts to investigate draw her into ever murkier territory, political and personal. Back in London, Daniel realises he's being used as a pawn in the struggle between those who want to bring peace to Ireland and vested interests set on prolonging the war. As the plot darkens, it becomes clear that most of the people in this story are traitors of one kind or another – some deliberately, and perhaps bravely, like Daniel; others drawn gradually over the line.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 487

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedalus Original Fiction in Paperback

BORDER LINES

Ros Franey’s first novel Cry Baby was published by Dedalus in 1987 and reprinted in 2023 as part of the Dedalus Retro list.

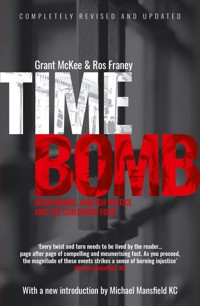

She has worked as a journalist and producer of television documentaries and has written non-fiction as well as fiction. A revised and updated edition of her book about the Guildford bombing case and the IRA, Time Bomb, written with Grant McKee, was published in 2024.

Border Lines is her third novel.

Published in the UK by Dedalus Limited

24-26, St Judith’s Lane, Sawtry, Cambs, PE28 5XE

www.dedalusbooks.com

ISBN printed book 978 1 915568 73 1

ISBN ebook 978 1 915568 76 2

Dedalus is distributed in the USA & Canada by SCB Distributors

15608 South New Century Drive, Gardena, CA 90248

Dedalus is distributed in Australia by Peribo Pty Ltd

58, Beaumont Road, Mount Kuring-gai, N.S.W. 2080

First published by Dedalus in 2025

Border Lines copyright © Ros Franey 2025

The right of Ros Franey to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Elcograf S.p.A.

Typeset by Marie Lane

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A C.I.P. listing for this book is available on request.

To Elinor and Maya

who heard the start of this story

— and encouraged me to finish it —

when we walked in the west of Ireland

one January, long ago.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Glossary

Acknowledgements

Recommended Reading

CHAPTER 1

Autumn 1997

On the morning Daniel Booth’s life was to change forever, he made toast, fed the cat and set out for Whitehall, just as he did every day of the working week.

The document arrived in his morning mail. He knew it must be a mistake, yet his colleague Vernon Potts said mistakes were as impossible as a cash dispenser paying out the wrong amount of money. Daniel had noticed that although Vernon was new to the department, he was very certain of everything.

‘Computers don’t make mistakes,’ Vernon assured him. ‘The only thing to go wrong with computers is the human beings that program them.’ Daniel rummaged through the jumble of news releases, periodicals, information briefings on his desk and found the brown internal envelope: BOOTH, D, 105, his room number, handwritten. The error was human. A quick glance told him the document was about Northern Ireland: no surprises there. What was the British Army getting up to now? He started to read. It was in the form of a memo, most of it taken up with a list of places, numbers beside them. A few of the places he had never heard of but others were familiar, and not in a good way. Something about the document didn’t feel right: this was definitely not for him. Stuffing it back into its envelope, he took it to his boss, Tiffin, and pointed out the error.

‘I’m not cleared for this. It must be for one of the others.’

Major Tiffin was the senior information officer. ‘Damn cretins downstairs. Did you read it?’

‘No, Major.’ If the minister could lie to Parliament, he told himself, Daniel could lie to Willy Tiffin.

‘Good man. Done the right thing. Let’s see…’ He reached for the internal directory then, taking a new envelope from a stack beside him, wrote the correct address. ‘Thank you, Daniel. Bad mistake. Pop it back in the post, there’s a good chap. I’ve got to shoot off now.’ And he bustled out of the room.

Where was Tiffin sending it? The room number scrawled on the new envelope was an inversion of their own: 501, the executive floor. This document must be top secret. Daniel was about to slip it inside when his eye caught the paragraph at the end of the list. He froze. Within half a minute, he had read the whole thing, one hand steadying himself on the corner of his metal desk. Oh my God, he breathed. Who knew about this stuff? He read it again: it was surely untrue, yet here it was. He couldn’t just let this pass.

The office was deserted and, for once, quiet. Fluorescent lights in the high ceiling illuminated the tattered poster of the Red Devils at Harpenden Air Show. Daniel stood up. In the grimy glass masking the inner well that served the room with fresh air, he saw his mirrored face, the smudges of eyes beneath the hair his mother had called fair but was probably just mousy; a man who at thirty-five felt young, but sensed time slipping quietly away. He thought of the Official Secrets Act he had signed. Is this what it was for: obedience to a set of lies? Clear-headed, he knew he was about to behave badly; and that it was the only decent thing to do.

Carefully folding the top corners to conceal the memo’s reference numbers, he walked over to the photocopier and punched in his code. The start button flashed green. Daniel placed the sheet face down on the glass screen and pressed the button. The obsolete copier gave an intestinal rumble but no clean copy slid from its tightly strained jaws; instead, the flashing of three small orange lights and a message with a hint of menace: CLEAR JAM IN AREA 1 OR. Vernon’s internal phone rang. Sweat started from Daniel’s armpits. He reached across to Vernon’s desk and jerked the receiver off its hook. ‘Press Office.’

‘Oh, hello. Is that the press office?’

‘Speaking.’

‘Oh, hello. Consignments Section B12 here. I wonder if you can help?’

‘I’m afraid the officer you need isn’t here at the moment. Can you call back in half an hour?’

‘I’m sure you’ll do. I’m enquiring about copies of Form M11[b]/B ordered by your section last Thursday…’

Daniel could hear footsteps coming down the corridor. He felt as if arteries were about to explode through his chest. ‘Would you hold the line a moment?’ he asked.

Vernon swung through the door, the turn-ups of his slightly-too-short grey flannel trousers flapping at his ankles. Daniel’s phone rang. ‘Christ,’ said Vernon.

‘This one’s for you!’ Daniel waved the receiver at him.

Vernon, ignoring him, picked up Daniel’s phone instead. ‘MOD Press office. Sure. I’ll get him for you. Daily Mail,’ he said to Daniel. ‘Challenger 2. You look awful,’ he added. Daniel’s stomach turned over. They swapped telephones. As he listened to the man from the Mail, Daniel’s eyes ground into Vernon’s back.

‘Nothing to do with me, I’m afraid,’ Vernon was saying to the woman from Consignments.

‘Can you repeat that?’ asked Daniel, his mind on the incriminating document stuck inside the machine.

‘Call after lunch and speak to Miss Hare,’ Vernon instructed in a no-nonsense voice. He put down the receiver and strode towards the photocopier.

‘I’ll have to phone you back,’ Daniel told the man from the Mail. He put his hand over the mouthpiece. ‘It’s broken!’ he called to Vernon.

‘Bugger,’ said Vernon.

Daniel took the number of the man from the Mail, rang off and darted over to the copier.

‘I’ve got to distribute the submissions on the AS-90 by three,’ Vernon grumbled.

‘Bloody madhouse,’ Daniel agreed. ‘Phones going all over the place. Can’t get anything done. And I’ve got to go to the dentist this afternoon.’ He nudged Vernon out of the way. ‘CLEAR JAM IN AREA 1 OR…’ a second message appeared: ‘…REFILL CARTRIDGE’. Daniel started to fiddle with the release catch on the paper tray. To his relief it was empty. He refilled it, reset the copier and pressed the button. This time the copied memo peeled into the out-tray. Vernon had lost interest. Daniel carried both papers back to his desk. ‘It’s all right now,’ he said casually.

He slipped the original into the internal envelope Tiffin had addressed earlier and folded the copy into a blank envelope, sealed it and put it in his briefcase. Vernon had seen nothing. Then he opened the file on Challenger and dialled the number of the man from the Mail. Bloody tanks. It was definitely time to move on.

*

Perdita Burn stepped out of the restaurant and turned up towards Oxford Circus. Sushi. She felt for the toothbrush in her pocket, mindful of the hygienist. She had fifteen minutes to get to Welbeck Street.

She’d hoped the walk would restore her spirits, but the more she thought about what had just happened, the more unnerved she felt. It wasn’t supposed to have been a work meeting. She’d been surprised when Nick had arrived with his briefcase and a young man Perdita had never seen before.

‘This is terrific,’ said Nick, beaming at Perdita. ‘Must be—what? Eighteen months, at least.’ Perdita saw him notice the absence of her wedding ring. ‘You look great,’ he told her. She smiled back at him. Nick was her mentor: the man who had given her chances, trusted her judgement on risky occasions. It was for him her best films had been produced. Over the years they had become friends as well as colleagues. So why was this stranger to share their lunch? Perdita turned to Nick’s companion expectantly.

‘Oh, this is Jeremy,’ Nick announced. ‘I thought it would be good for him to come and meet the guru.’

Perdita felt neatly dated. She took in Jeremy’s expensive haircut, his designer jeans.

Nick was saying, ‘Meet the woman who brought us some of our greatest successes, Jeremy. I hope you two can form as good a relationship for the future… As I expect you’ve read,’ he told Perdita, ‘Jeremy is our new head boy.’

‘Congratulations, Jeremy!’ Perdita said. She wondered what this meant.

‘You didn’t see the piece in Broadcast?’

Perdita shook her head. ‘I always forget to read Broadcast,’ she admitted.

Nick’s eyes narrowed. ‘Unwise, Perdita. You need to keep up with it, otherwise you might miss the news of your own assassination!’ If she hadn’t read Broadcast, he continued, she might not know about the changes.

Perdita’s last two films had been for a different channel and she was suddenly on her guard. As soon as the waitress had guided them to a table, Nick in his laconic way informed her that there was to be restructuring in Factual. He’d still be around, of course, but Jeremy would be doing the commissioning.

As they talked, Perdita sipped at something she suspected to be seaweed tea and watched Nick carefully. He was looking tired, she noticed, and suddenly felt protective towards him. Had he persuaded himself that his promotion, if that’s what it was, would be as interesting as the money? Or had he been given no choice? She realised he was sticking his neck out to introduce her to the new man, and was touched. New men preferred new brooms. Jeremy looked bored.

Despite its menu the restaurant was workaday, no-nonsense. It was not a place you took people for atmosphere.

‘Sorry it’s not Zulu.’ Nick grinned at Jeremy. Jeremy shrugged. Perdita knew Zulu. She had once taken her daughter Daisy there on demand. It was full of people like Jeremy. Perdita knew Nick knew Zulu wouldn’t do for Perdita, because Perdita was too old. ‘Zulu is so noisy,’ said Nick.

As lunch continued, it became clear she was on trial, to be judged by her new ideas. Nick might at least have warned her!

‘…Why Afghanistan?’ Jeremy was asking. ‘So eighties, isn’t it?’

Perdita turned to him, startled. ‘Under the Taliban,’ she began, ‘women are now being excluded from hospitals: just think what that actually means. There’s a doctor in Kabul who runs a secret mother-and-baby clinic from her house. She’s agreed to let us film—’ She broke off. Jeremy was shaking his head.

‘It’s niche, Perdita.’

She blinked. ‘It’s half the population of the country!’

‘…and it’s subtitles,’ he finished.

Pointless to argue, but Perdita felt a small explosion of rage. ‘The doctor trained in Bristol,’ she told him evenly. ‘Her English is perfect.’

Nick leaned the elbows of his suede jacket on either side of the sushi and said, ‘I’m afraid people aren’t interested in those things, Perdita. But look at the outpourings last month over Princess Di’s death! We should all take lessons from that. A landmark in history wrapped in a story that viewers can engage with.’

Perdita was uneasy. ‘Not exactly my territory, is it, all that?’

‘Of course not. But what about the response to Helstone B: that got them going, didn’t it? Everyone can relate to workers and their kids living under the threat of nuclear contamination. You exploded Britain’s bomb!’

For the first time since they had sat down, Perdita sensed the return of Jeremy’s attention. ‘What do you want?’ she asked cautiously. ‘If I’d come with more of that, you’d have told me the world’s moved on.’

‘It set the agenda for an important debate about risk and the price of progress,’ Nick assured her.

Jeremy put in, ‘We want the same appointment-to-view applied to an issue for today.’

This wasn’t exactly radical: there must be a catch. ‘So…’ she ventured, ‘we could look at refugees arriving here. The British government are sending back asylum seekers, splitting families, breaking international law, right on our doorstep.’

‘Well, that’ll really get the advertisers going,’ Jeremy said.

Nick frowned at him. There was a silence.

Perdita decided she needed to behave herself. ‘Okay, so what’s this year’s “landmark”?’ She paused. ‘How about Ireland? The peace?’

Jeremy and Nick exchanged glances. ‘Indeed,’ said Jeremy. ‘Ireland at the crossroads.’

She nodded. This was more interesting.

‘End of the Troubles: hands across the border,’ he went on. ‘The fusion of two cultures. Two great industries with fractured ideologies: Irish tweed and Ulster linen.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Think of it as a metaphor,’ Nick suggested. ‘Unity? Unification?’

‘Why?’

They both spoke at once. ‘WGBH—’ Jeremy began.

‘Cashmere was a huge success,’ said Nick. ‘Multi-layered, you see.’

‘Fabulous shots.’

‘Hang on.’ Perdita held up a restraining hand. ‘You’ve made a film in Kashmir, then?’

‘Not separatists. Of course not,’ said Jeremy impatiently.

Nick explained, ‘Wool.’

‘Wool?’

‘The Cashmere wool story. This would be a sort of companion piece.’ He couldn’t quite meet her eye as he said it.

‘We’d have complete editorial freedom, of course,’ Jeremy interrupted. ‘Co-producers would be nowhere near it.’

‘So that’s not niche then?’ She threw them a mischievous look.

Jeremy snapped, ‘We can’t continue to make your kind of films, you know: worthy, open-ended investigations that don’t earn their keep and—let’s face it—viewers won’t come to.’

Perdita, furious, shot back, ‘And the Princess Diana connection is…?’

Nick intervened gently, ‘Heritage, Perdita.’

She was still glaring at Jeremy. ‘Why me, anyway? If my films are so boring, what’s all that stuff about Helstone?’

‘You, because we want a grown-up on the subject,’ Nick said.

‘Oh yes. Appointment-to-view.’ She felt wretched at taking it out on Nick because she knew it was not his fault. He was trying to help her—perhaps it was the last time he would have the power—to ease her passage into this tame new world. Maybe that’s why he was getting out.

Jeremy drawled, ‘It’s not a regional commission, you know. Edit right here in Soho. But, hey, if you’re not interested, I’ve plenty of other people on my list who are… Actually. Directors the Americans already know.’ He didn’t look at Nick as he said this. Perdita understood she would not have been on his list at all.

‘This is the millennium, Perdita,’ Nick explained, and the set of his shoulders confirmed her worst suspicions. ‘Digital. And co-production is it.’

Turning into Welbeck Street, Perdita tried to shake off her despondency. Of course, she had known this was coming— everyone knew. But to receive news of one’s own assassination, as Nick might put it, over lunch, was a shock. Were pointless films like this to be her future, then? As she climbed the stairs to the surgery, she realised she hadn’t told them whether she would do it.

The small waiting room was empty when she entered, apart from a youngish man sitting in the corner, reading. Perdita breathed deeply. She was a little late. She laid her jacket over the arm of the sofa, propped her briefcase beside it and picked up a copy of London Portrait. The shag-pile carpet was looking pretty dated, she noticed; they would change it soon. Most of the patients were private these days though not, she decided, this man here: he somehow didn’t seem the sort, with his serious-looking book and preoccupied air. Perdita took in these things automatically, but was too distracted to dwell on them. She turned the pages of the magazine and tried to forget about lunch.

Daniel was sitting in the waiting room thinking about Sarah Tisdall. His first instinct had been to post the memo to The Guardian, but their behaviour over the young civil servant who had leaked a document about cruise missiles, deterred him. The newspaper had revealed the source of the documents and Tisdall went to prison—and that was fourteen years ago, before the removal of the public interest defence in Section 2 of the Act.1 Daniel clasped his briefcase tightly underneath the book on his knee. It felt as if the document inside were pulsing with plutonium.

When the waiting-room door opened, he hoped it would be the nurse to summon him, but instead he saw a slim woman with reddish hair who must have been another patient. She had wide grey eyes that made her look young, though she was probably older than him. As soon as he caught sight of her, he knew with a jolt he had seen her before. Daniel looked swiftly down at his book. He had met her only once apart from watching her on television—oh, it must have been at least two years ago, when he was at the Electricity Office. He couldn’t remember her name—something odd—but he clearly recalled the meeting at which they had tried to persuade her to make changes to her film. She had refused, of course, and it had given them a headache in the press office when the uncut documentary was eventually shown, but he was glad the truth was out. The injunction, and the lifting of it, had made her quite a celebrity, if you counted a ten-minute rule debate in Parliament; interviews on Channel 4 News and Newsnight. Helstone B: it had dominated their lives for a while. How weird that of all people, of all days, he should meet her now.

The door opened again. This time it was the nurse. ‘Perdita Burn?’ Yes, that was it!

She threw aside her magazine. ‘Thanks,’ she said. For a moment, she hesitated over the coat and briefcase. Then she walked to the door.

Now the room was empty. Daniel’s heart slammed backwards and forwards against his ribs. He had intended to take the document home, sleep on it, think through what he was doing. Where was Alex when you needed some sound advice? They had always relied on each other for that. Should he pass the document on—if so, to whom?—or tear it up, forget about it?

Perdita’s briefcase leaned against the arm of the sofa where she had left it. Seize the moment: that’s what Alex would say. His hands were shaking so much he could scarcely close the book he was reading. The envelope. Should he write on it and, if so, what? ‘Ms P. Burn’? Too premeditated. ‘To Whom It May Concern’? Handwriting experts might trace him. Nothing, then. The briefcase would be locked. No, it had buckles. His fingers were sausages. The nurse would return; catch him. Courage. Calm. The bag was seven feet away. Do it now… well, now, then. Undo. Slip inside. Three seconds. In ten seconds, he could be sitting back here again.

Daniel returned to his seat, twitching. This was treason. He had done it. Crossed over. Pushed the rock off the edge. It was already falling. He must stop it. Can’t stop it. Can. Take the envelope back again. Burn it as soon as he got home. Ten seconds and he could be safe—

‘Mr Booth? The dentist will see you now.’

Daniel jumped. ‘Oh, yes,’ he said. He stood up.

The nurse smiled. ‘He’s very sorry to have kept you waiting.’

1 This is the Official Secrets Act 1989. Section 2 removed the ‘public interest’ defence from the earlier Act of 1911—i.e. you could no longer defend yourself in court by claiming that contravening the Act was justifiable in the public interest.

CHAPTER 2

It was Perdita’s day for seeing Hugh. This was a throwback to the mediation that had followed the breakdown of their marriage, a forum—the mediator’s word—for discussing Daisy, their nineteen-year-old daughter.

Daisy pretended to disapprove. ‘Why put yourself through it, Mum? It makes no difference to me. And you always come home in a bad mood.’

‘I don’t see him for you, my love. I see him for me.’

‘Why?’

‘Because.’ Because at some level she needed to explore the sense of failure that still, after four years, pervaded her; to understand the feelings they had once had for each other; to reassure herself that things were happier now.

Reading her thoughts, Daisy said, ‘You’re better off without him, Mum. You’d still be tiptoeing round his horrible tempers. Just think how screwed-up I’d be if you’d stayed together.’

‘You’re supposed to be screwed-up because we didn’t.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Daisy crossed her eyes and waggled her fingers in the air.

‘You’ve suppressed it. I’m suspicious.’ Perdita was laughing.

‘Damaged, either way.’ Daisy stuffed her purse into the pocket of her denim jacket. ‘Does this skirt make me look fat?’ And without waiting for an answer, ‘You ought to go to Henne’s. Brilliant long frocks. Your sort of thing.’

‘I thought you wanted me in skirts above the knee?’

‘Oh, I’ve completely given up on that.’ She kissed her mother. ‘I’ll be back—not late. Promise not to talk about me.’ And she was gone.

Perdita had omitted to tell Daisy that she was meeting Hugh tonight at what he insisted on calling ‘his club’. If anything could be guaranteed to generate further scorn, it was that. Perdita sighed. Hugh was far less self-important with his daughter than he was with her. Daisy simply wouldn’t let him get away with it. Perdita, who didn’t suffer fools in the outside world, admitted that at one level she was still in awe of Hugh. Perdita had heard Daisy say, ‘Dad, Pur-leez,’ and he would grin sheepishly, run his fingers through his hair muttering, ‘Child’s got no respect,’ and change the subject.

Waiting at the draughty porter’s lodge for Hugh to come and collect her, Perdita’s thoughts returned to the document that had mysteriously appeared in her briefcase three days earlier. Her bewilderment was swiftly overtaken by disbelief, and then by alarm, as she read it. Sketchy as it was, her knowledge of Ireland and its interminable peace process was sufficient to convince her that if this memo were genuine, highly unorthodox tactics were being used by the British government; tactics that, made public, would blow the shaky peace apart. Aside from the shock of its arrival, Perdita had been preoccupied with the question of whether to tell Hugh about it. She badly needed an expert opinion. Where had the document come from? How secret was it? Was it real, or a fake? And, above all, why her and what should she do? This was Hugh’s province. Could she trust him? Each time she asked that question, it remained unanswered. Now it was time to decide and she simply didn’t know.

‘Darling. Sorry, darling. Have you been waiting an age?’ He kissed her briefly on the cheek. He was wearing, she noted, the most peculiar tie. Daisy had said nothing about a new girlfriend, had she? Perdita found the tie oddly cheering.

They climbed the enormous staircase to dinner, Hugh informing her—not for the first time—that its extra handrail had been installed for Talleyrand who, as the disabled French ambassador, had been a regular visitor in the 1830s. A man who switched sides, Perdita reflected to herself: perhaps that’s why he appealed to Hugh. This amusing thought was interrupted by Hugh abruptly changing the subject with, ‘So your chaps are in trouble again, I see,’ and her spirits wilted. This was a reference to an old spat between them, central to the breakdown of their marriage and, in the end, it came down to politics.

Hugh was the Port Talbot steelworker’s son who left school at sixteen to work on the local paper; learned his craft the hard way in the days of the great investigations. He was a newspaperman of the old school who had defected effortlessly to the new. When Perdita met him, he had been a name to conjure with: she had been very young and very beguiled. At twenty-three he had introduced her to the writing of Wallraff and Tom Wolfe. At twenty-five she had borne him their child. For a while the imbalance suited both of them. She could date the seeds of doubt to his promotion. While numbers of his colleagues preferred to slip away and find other jobs after the newspaper group changed hands, Hugh had seized his destiny. His disdain for the kind of television documentaries on which she had begun to work became more elaborate as their careers diverged. ‘Her chaps,’ Perdita comforted herself, were these days often more ethical than Hugh’s own.

She waited for him to ask about Daisy but he didn’t, preferring, over the potted shrimps, to tell her in detail about a trip he had made in the summer to what he still called the Far East, as one of the journalists following the new Prime Minister around. Perdita wondered if he had always been as pompous as this.

A waiter brought a bottle of the Club claret. ‘Would you like to taste it, sir?’

‘Of course I’d like to taste it,’ Hugh said. He did so. ‘Yes, okay.’ Then to Perdita, not bothering to lower his voice, ‘See what I mean? They haven’t got a clue here.’ The waiter frowned as he poured the wine. Perdita smiled her thanks to him. ‘You want to go to Singapore,’ Hugh told her. ‘That’s the place for first-class service.’

Perdita decided it wasn’t worth reminding her ex-husband that she had lived in Malaysia as a child, so she simply agreed that, yes, service there was excellent—and changed the subject.

‘Did Daisy tell you she’s been working in a solicitor’s office for the last few weeks of the holidays?’ she asked him.

Hugh looked pleased. ‘Good girl,’ he said. ‘About time!’

‘She doesn’t get paid for it,’ Perdita explained hurriedly. ‘It’s work experience.’

‘What’s the point of getting a job if she’s not paid?’

‘That’s the system. I thought you’d approve.’

‘When’s she going to start earning her own money? And how long am I supposed to go on supporting her? Little madam,’ he added affectionately.

The wine was at last beginning to have a mellowing effect on both of them. A dessert trolley clinked past their table, cut glass and sponge cake. Perdita gazed around at the dark-suited diners, candle flames reflecting back at them from vast spotted mirrors hanging on the walls, while their voices set a low echo murmuring down from the ceiling high above. This scene, she imagined, had probably changed little since the 1930s. The club still reeked of intrigue, which fascinated her. How many secrets had been confided here? Hugh would not betray her. He would offer practical advice. He might not respect their marriage vows, but if she told him a professional secret strictly off the record, he would surely honour that. The desire to confide in him began to rise unstoppably to her mouth. ‘Hugh, I want to ask you something.’ She paused and took a sip of wine for courage.

‘Ah!’ His eyes lit up for the first time that evening. But they were not looking at her. Perdita felt a presence behind her. Unusually for him, Hugh rose to his feet.

‘So sorry to intrude,’ came a voice that clearly wasn’t.

‘Not at all, Sir,’ said Hugh, beaming. ‘I was told you might drop in. I was hoping to catch a word with you.’ Perdita forced herself to smile up at the lean figure that had now stopped beside their table: he had wavy, greying hair and the expression of a man confident of being listened-to. She guessed he must be a politician but she didn’t recognise him. Hugh did not introduce them.

‘Are you here for a while?’ The man raised his eyebrows.

‘Sure. Whenever,’ said Hugh. ‘It won’t take too long.’

‘How about coffee in, say—’ he glanced at his watch. ‘Can you make it in fifteen minutes?’

They were only halfway through their main course. Perdita looked down at her cooling plate. This was so familiar.

‘No problem,’ Hugh told him.

The man moved on. Perdita scowled.

‘Clive Blakemore,’ explained Hugh. ‘Busy man.’

‘Evidently,’ said Perdita.

‘Got his hands full. We’re doing a profile next week. Delicate stuff. He’s having a hard time.’

‘So that’s why you wanted me to meet you here.’ She heard an edge to her voice that she didn’t like, but what the hell. ‘Never let it be said Hugh Williams spent too much time with his family,’ she teased.

‘Sorry I didn’t introduce you,’ said Hugh, misunderstanding. ‘Bit awkward. Don’t know what to call you these days. “This is my ex-wife,” sounds rather crass.’

‘Not really. They’re all screwing their research assistants, aren’t they?’

‘Not Blakemore. Married rather late, actually. Younger wife. Small kids. You ought to watch yourself, darling. You’re starting to sound crabby.’

It was nine forty-five when Perdita reached home; thanks to Clive Blakemore she had left earlier than expected, her secret unspoken. A long hot bath seemed suddenly to be a priority. She stood in the bathroom with the bottle of bath oil in her hand, wondering at her jangled nerves, then fetched the radio, climbed into the bath and lay immobile in the heat till The World Tonight news was over.

Meetings with Hugh still produced in her a rage she couldn’t express. Perdita shivered and slid further down into the water. Five minutes later, wrapped in a towel, she pottered next door into her study, leaving a trail of footprints on the carpet behind her. She took down a small blue book, Vacher’s Parliamentary Companion. A committee clerk friend passed on duplicates; this was the latest edition and listed the new cabinet. Section Three: Chief Officers of State. Who was this man who had messed up her evening? She knew the name but couldn’t place him. Was he a Parliamentary Under Secretary, or something? Not exactly. She caught her breath. Clive Blakemore, MP. Of course he’s having a hard time: he’s one of the new junior ministers in the Northern Ireland Office, working to the Secretary of State. This document of hers: he might very well know. Thank God she hadn’t told Hugh.

Suddenly in the hall, the doorbell rang.

It was half-past ten. Damp and vulnerable, still wrapped in her towel, Perdita stood by the Entryphone. The doorbell rang a second time. Perhaps Daisy had forgotten her keys.

‘Yes?’

‘Mrs Burn?’

‘Who is it?’

‘I’m sorry to call so late. I came earlier, but you were out.’

‘What do you want?’

‘We met, well we didn’t actually meet, but—’ the intercom crackled.

‘What?’

‘We share the same dentist: 34 Welbeck Street.’

Perdita froze. ‘Who are you?’ she asked at last. ‘You’re not supposed to be here.’

‘I have to talk to you.’

‘Why?’

‘Mrs Burn, please. Isn’t this your job?’ There was urgency in the distorted voice. He was right, of course. Here was the one person who could enlighten her. Perdita hesitated. It could be the police. It could be anyone. It was madness to admit strange men to one’s home at night, but this would be her only chance to meet the sender of the document… and Daisy would be home soon. She pressed the downstairs buzzer and hurried back into her bedroom to throw on jeans and a sweater. Then, as footsteps came upstairs, she opened the flat door on the chain. When she saw it was the diffident youngish man half-remembered from the dentist’s, she slipped the chain and opened the door wider.

Without speaking, he entered the hall. He looked chilled through, as if he’d been hanging around in the cold for hours. They examined each other for a moment in what she felt was mutual dismay. Perdita had a confused impression of a stripy scarf and the face of an embarrassed angel in an English church.

‘I’m so sorry to alarm you,’ he apologised.

‘Who are you?’ she asked again sternly, trying to keep the nerves out of her voice.

‘I’m sorry. Daniel Booth. Ministry of Defence.’ He held out his hand. Are we conspirators? she wondered, as she took it.

She led him into the sitting room, running a hand through her damp hair. ‘You’d better have a drink,’ she said, in an effort to impose normality on a situation she found totally unnerving. ‘There’s nothing except wine—unless you want a cup of tea.’

‘What are you having?’

‘I’m shaking. I need a drink.’

‘So am I,’ he said. ‘Yes please.’

She took his coat and went to open a bottle. ‘How did you find me?’ she asked, returning with two glasses.

Daniel sat down on the sofa, briefcase beside him. ‘Mr Hudson’s been my dentist for years. Your name was in the appointment book; your address on the, you know, Rolodex thing.’ He made a vague circular movement with his hand, pleased with his sleuthing. ‘I didn’t check it out till yesterday. I’ve had a difficult week. I didn’t know what to do.’

‘The reluctant traitor,’ Perdita said. It was meant to be a joke but it seemed to re-awaken his anxieties; the look on his face was suddenly haunted. ‘Forget it,’ she added hurriedly. ‘That is, I’m sure most traitors are reluctant. Anyone who acts out of conscience must be all too well aware of the danger.’

Daniel was staring into his glass. ‘I was always brought up to be honest, you see.’ The look of embarrassment returned. ‘Sounds old-fashioned, doesn’t it?’

‘I hope not,’ she murmured, and waited for him to continue.

‘You sign the Official Secrets Act. It’s a serious thing. Chaps like me, we get totally institutionalised, you know.’ He cast her a self-mocking glance and dropped his eyes to the glass again. ‘You really don’t think you’ll ever do a thing like this.’

She was expecting further self-criticism, but when he looked up at her his eyes were twinkling. ‘It’s been coming on for months, you know,’ he confided. ‘This sense that the job I do, the whole place, is completely bonkers.’

His expression was so guileless she couldn’t help warming to him. ‘Why did you do it?’ she asked, intrigued.

He thought for a moment. ‘Two tenets: honesty and doing your duty. Which do you think is the stronger?’

‘I’d hope they’d be indivisible,’ she said, smiling.

Daniel shook his head. ‘That’s where you’re wrong. It’s why I’m in this mess. What happens when it’s a dishonest duty? The bastards never tell you that!’

She said nothing, and he went on, ‘To start with, it was easy. What I read in the document was so unthinkable that I couldn’t give a damn about signing some stupid Act. Now—’ he sighed. They were both silent for a few moments.

Then he asked, ‘Have you shown it to anyone?’

‘Not yet.’

A look of relief crossed his face. ‘I came here to get it back,’ he said simply.

‘Why?’

‘Does it matter?’

‘Of course it matters.’

‘Cold feet. Allegiance to the crown. In that order.’

Perdita smiled. She might have felt the same.

‘If you want to know,’ Daniel went on, ‘I’m scared witless.’

‘So am I,’ said Perdita.

‘You? Why?’

‘Because I’ve read it. Why d’you think? If this is what governments do in our name, I don’t trust anything any more.’ She watched the effect of her words on him. ‘Which is why I’m not going to give it back,’ she finished quietly.

‘What do you mean? You’ve got to! Perhaps I didn’t make myself clear. I’ve decided not to leak it after all.’

‘Unleak it?’ She started to giggle.

‘Why not? It’s my document!’ he argued.

She raised an eyebrow.

‘All right, then. It’s my head on the block. You can’t force me to be a martyr!’

He was right, of course. She could give it to him now. Say it never happened; so much easier. For a full moment she was tempted to hand it over.

‘But… you did it for a reason,’ she said gently. ‘I don’t know who you are or what you do, but when you read this memo you felt so strongly that the public have a right to know what’s going on, you risked your moral welfare and your career in the civil service to pass it to me. Yes?’

Daniel nodded.

‘Okay, then. So let’s discuss how we proceed.’

‘We don’t do anything,’ Daniel protested. ‘If you won’t give it back, it’s down to you. You’re the investigative journalist!’

Perdita laughed. ‘That’s more like it. So. Some questions. I haven’t done anything with the document yet because I wondered if I’m being set up.’ She watched as this sank in, but he blinked at her in apparently genuine surprise. ‘First, I’m not a public figure,’ she explained. ‘How did you know who I was? Second, you meet me by chance at the dentist. In this world how many things happen by chance? Third, I imagine if it’s genuine this is a very restricted document. I want to know why someone with access to such material wants to leak it to the media.’

‘I got it by mistake,’ Daniel interjected.

‘Okay. By mistake. But whose? Why should I think this document is genuine?’

‘Look,’ said Daniel. ‘Isn’t it enough that I’ve changed my mind? If you don’t like it, give it back to me. I didn’t lie awake for hours, you know, planning on who to pick from my vast acquaintance of hacks. You’re not so special! The document happened. I took my chance. I had to pass it on quickly. I bumped into you in the waiting room. It seemed the right thing at that moment to entrust it to you!’

‘Okay…’ She took this in. ‘But how did you know who I was?’

‘Helstone B,’ he answered promptly.

‘Ah. You saw me on Newsnight? You’ve got a good memory.’

‘Not just then. We sort of met. DTI2—when you came for that meeting? I was sitting at the back.’

‘I see,’ said Perdita slowly. She remembered a room somewhere in Westminster dominated by a polished oval table; three civil servants ranged around it, facing her and her executive producer; more stationed in chairs against the wall behind. It was starting to fit.

‘I thought you did it out of decency, Helstone,’ Daniel went on. ‘We all knew the safety procedures were inadequate. There was nothing we could do. You gave us a terrible time in the press office, but I was delighted.’

‘Second mystery. You’re a press officer, then. I should have thought you had your own contacts.’

‘My contacts are the defence correspondents.’ He rolled his eyes. ‘I thought that what my document needed was some objectivity.’

There was silence for a moment. Perdita said, ‘So do you still want it back, or may I refill your glass?’ Before he could answer, she reached for the bottle. Then, remembering her encounter from earlier in the evening, she said, ‘Tell me something. Do you know anything about Clive Blakemore?’

Daniel frowned. ‘How do you mean?’

‘The minister. Apparently he’s under a lot of pressure from Sinn Féin.’

‘Oh, that. Not so much Sinn Féin, is it? More the Unionists.’ She noticed Daniel spoke with authority, but immediately qualified it with, ‘Of course, it’s not my Ministry.’

‘No, of course not.’ She returned to the matter in hand. ‘So, who did this document come from?’

‘I don’t know, do I?’ he said. ‘It’s not me, all this. It’s all very well for you smart bloody journalists. You aren’t schooled in secrecy the way we are. You don’t understand the importance because you don’t have to face the consequences of what happens next.’

Perdita said, ‘Daniel, I don’t want to give it back because—well, it’s a bloody good story. And I can’t give it back because—’ she sighed. ‘I don’t know. We’re living in odd times for my job. I suppose I’m stubborn and old-fashioned— like you, perhaps?’ She shot him a brief smile. ‘So I don’t want to walk away from it, and I don’t think you want me to.’

She waited. When he raised his eyes, his face was a picture of indecision.

‘I can’t believe it’s genuine,’ she mused. ‘But, if it is, the peace will go sky-high. Of course, it isn’t the sort of thing that could be used on its own. It would need a lot more research.’

Daniel found this reassuring: she didn’t intend to publish immediately, then. ‘But I don’t think I can be any more help, Mrs Burn,’ he told her. ‘I don’t know anything else.’

Perdita ignored this. ‘Have you got five minutes?’ she asked suddenly. ‘And please don’t call me Mrs Burn. Stay there.’ She left the room before he could object, returning a minute later with the document. ‘Now. Tell me what this means to you?’

Daniel reluctantly took the memo from her outstretched fingers. Was she handing it to him to test him, he wondered? To see if he would give it back?

‘This one: Keady 15.10. What’s that?’

‘I couldn’t make it out,’ he said slowly. ‘I thought at first they were code numbers or times, but this one, here, makes it fairly clear they’re dates: Lisburn 07.10. I think that must be last year: two car bombs at the British Army HQ. You can imagine the problems that gave us!’

She could well imagine it. ‘Yes. And then there’s the next one, just recently: Markethill 16.9. That was the very day after Sinn Féin joined the talks. They’ve both done the peace process a lot of harm. Yet if this astonishing document is genuine, the security services, the government, had prior knowledge—perhaps even played a hand… I can’t believe it. I’m sorry, I can’t.’

‘Actually,’ Daniel said, ‘I’m pretty sure the Provisionals denied that one. It’s said to be one of the breakaway groups. Gerry Adams was all over the place, insisting the ceasefire’s intact.’

‘I simply can’t believe the British would sabotage their own peace!’ Perdita repeated. ‘And what about the final date? I couldn’t find a reference to Keady on October 15th of any year, could you?’

Daniel shook his head. ‘I looked it up. Keady’s a small town near the South Armagh border. There have been a number of bombings around there over the years. It must be one of those. After all—’ he shrugged. ‘Don’t they call it bandit country? I guess they go unreported half the time. You’re right. It needs more work.’

‘Whether it’s true or not,’ Perdita said, ‘someone must want to screw up the talks, particularly now Sinn Féin are on board. But what’s this got to do with me?’ She reached out and touched his wrist to soften what she was going to say next. ‘And if I’m not being set up, Daniel, perhaps you are.’

Daniel withdrew his hand. ‘That’s ridiculous!’ he muttered, but Perdita caught a flicker of something in his eyes that she couldn’t place.

‘I don’t believe the document is real,’ she said. ‘If this is true, we’re living in madness, a mad state. Forget your code of silence. Forget my job. We have to expose it. But if the memo is a forgery, why send it? There are no chances. Not like this, there aren’t. You didn’t receive it by accident. Either you are trying to trap me, which only you can know?’—she left the question hanging in the air for a moment—‘…or someone wants you in trouble, Daniel. You can’t just put this behind you.’

Daniel stared at her in bewilderment, but he was listening closely.

‘It’s not my subject,’ Perdita went on. ‘I invited you in tonight partly out of curiosity. Couldn’t believe anyone would take me seriously enough to want to frame me. But partly because, having read it, I felt I had no choice. And now I’ve talked to you—’ she broke off. How could she explain that she felt he was an innocent in dangerous waters? ‘I believe what you say,’ she continued. ‘I believe in why you’ve done it. I want to help you.’

Daniel had no doubt she was sincere. He felt numb. ‘I don’t understand,’ he said. ‘Why should anyone want to get at me?’

‘Will you trust me?’ she asked.

He gazed at her. She had turned his world upside down. He gave her a rueful smile. ‘What else can I do?’ he said.

2 Department of Trade and Industry. For other abbreviations and translations, see Glossary (pages 373-5).

CHAPTER 3

The clerk at Reception was deeply concerned. ‘There’s still no message, Ms Burn. I’m terribly sorry.’ If she could have conjured a message out of the telephone she would have done it.

‘Bother,’ said Perdita.

‘People are so rude, aren’t they?’ the young desk clerk sympathised. ‘They promise to phone back and they never do. Still,’ her face broke into a mischievous smile. ‘It’d only be work, now, wouldn’t it? Nothing really serious.’

Perdita laughed. But it was becoming serious. She had been trying for more than two days and still no word from Sinn Féin. She must leave Dublin shortly for the North. She turned away from the desk, past the peg-board announcing today’s functions, and ducked back into the conference suite under the huge banner: Tweed Awareness Week. Against life-sized blow-up photographs of apple-cheeked men sitting at looms against a backdrop of the mountains of Donegal, patrons shuffled from stall to stall fingering textiles and talking earnestly of weight and density, warp and weft.

*

‘You will do it!’ Jeremy had not been able to conceal his surprise at Perdita’s decision.

‘Yeah, sure.’ Perdita didn’t want to sound over-enthusiastic.

‘Well, I think you’ll enjoy this more than you imagine,’ Jeremy said. ‘Fascinating time to be in Ireland,’ he added. ‘They say the whole place is booming these days.’

*

Jeremy would not have realised, of course, that her research into tweed would take her to the offices of Sinn Féin, where signs of the new affluence were sketchy. The makeshift security cameras were evidently working, but otherwise none of the funds raised by senior republicans on their tours of Australia and North America seemed to have filtered back to the oncegracious house in Parnell Square. Perdita noted the chunks of plaster lying in an unswept avalanche at a bend on the wide stone stairs; the chill and the dark of it and the frayed carpet tiles at the top, almost obliterated by yellowing stacks of the republican newspaper An Phoblacht, which confirmed she had reached the publicity department.

‘I’ve come to see Fionnuala James,’ Perdita said to the blonde young woman at the desk behind the newspapers. ‘Perdita Burn. I’m afraid I’m a little late.’

The blonde young woman examined her for a moment and then opened a large desk diary. She turned the page to the correct date. The page was blank. After scrutinising it with care, the young woman said, ‘Fionnuala isn’t here just now.’

‘I’ll wait, shall I?’ asked Perdita. The young woman looked uncertain. Then she called into an inner office, ‘Eddie!’

A young man appeared. He was wearing track-suit pants and a t-shirt inscribed Collusion Kills. He stared first at Perdita, then at the blonde young woman, who explained, ‘She’s come to see Fionnuala.’

‘Fionnuala isn’t here.’

‘I had an appointment for midday,’ said Perdita.

‘Where are you from?’

‘I’m a TV producer. ITV?’ she added, uncertain whether this would help. She handed them a business card on which she had written the number of her Dublin hotel. They both ignored it.

‘But where from?’

‘Oh. England. London.’

Eddie scratched his head. ‘She’s away.’

‘Away?’

‘She’ll not be back.’

They all considered this. Perdita had an idea. ‘Friel sent me.’

‘Martin Friel? RTÉ?’ Eddie’s face brightened.

‘That’s right.’

‘How is Friel?’

‘He’s fine. He has two babies. Twin boys.’

‘Friel? That’s grand.’

‘He’s based in London now.’

‘We had some serious nights with Friel,’ Eddie recalled.

‘I used to work with him,’ Perdita said. ‘He contacted Fionnuala for me.’

‘Ah. Well.’

‘She’s away,’ said the blonde young woman, closing the desk diary. Perdita began to feel dispirited. ‘When will she be back?’ she asked.

Eddie regarded her as if weighing something up. ‘Tomorrow,’ he replied after a moment. ‘Aye, she’ll see you tomorrow. Tell Marty I was asking for him. Twins. Jesus!’ And he turned back into the main office.

Perdita was left with the blonde woman. ‘What time shall I come tomorrow?’ she asked.

‘It’s hard to say.’

‘Ten o’clock?’

‘Oh no.’

‘So give me a time.’

‘Will I get her to phone you?’

‘I’d rather say a definite time now. I have to leave Dublin tomorrow afternoon.’ This was not strictly true, but the deadline was borne of experience.

‘Sure, she’ll phone.’

‘Can I leave her a note?’

‘I’ll tell her. No problem.’

‘It’s very urgent.’

‘Sure. I’ll say Martin Friel’s friend.’

And that had been that. Perdita had called regularly throughout the following morning. Yes, Fionnuala was back. Sure, she had the message. She was in a meeting just now… The meeting was over but she was on the other line. No, it would not be possible to hold because there were no further lines into the office. Fionnuala would call her right back. Nothing.

Perdita found herself gazing into the eyes of a large wooden sheep with a real fleece. The sheep looked sympathetic. The conference crowds were starting to thin and Perdita longed to leave too. Her throat ached from talking to weavers, dyers, sheep breeders and market researchers against the airless buzz of conversation. In normal circumstances it would all have been straightforward enough, but failure in Parnell Square ate into her. Suddenly, two voices penetrated her absent mind.

‘For the last time, I am not wearing that!’

‘One of our most popular designs, Sir.’

‘Will you get away! It‘s like two sick sheep have thrown up in a bog.’

Perdita turned and found herself smiling up at the good-looking man with unusually pale blue eyes who had spoken these words.

He instantly appealed for her help. ‘Would you look at this now? Grotesque, isn’t it! He tells me it’s one of their most successful designs.’

‘We sell miles of it every year,’ said the salesman, who found the whole thing hugely amusing. ‘To Americans mostly.’

‘Well, there you have it!’ cried the blue-eyed man. ‘But we shouldn’t be pandering to bad American taste.’

‘I thought everyone had to do that,’ said Perdita.

‘Not a bit of it,’ he responded. ‘Americans have to take us as they find us. Good American taste is better than ours, of course. We have built a proud trade on quality and British good taste. Americans love it—at least, East Coast Americans do.’

Perdita regarded him. ‘Irish good taste?’ she suggested with a smile.

‘No, Ma’am. I’m not in the tweed business. Ulster linen. British taste. Don’t teach your grandfather to suck eggs. You’d better come and have a cup of tea.’

He turned and led the way out of the conference hall and back into the hotel foyer where it was quieter. Perdita followed meekly. Whoever he was, he was good for research. The only free seats were positioned on the far side of a large flower arrangement. Without consulting her, the man threw an order for tea to a passing barman and sat down.

‘Ian Frazer,’ he said, introducing himself. ‘How do you do?’

‘Mr Frazer!’ cried Perdita, appraising him with new interest. ‘I’m on my way to see you in Belfast. We have an appointment for Thursday. I’m Perdita Burn from London.’

‘Well, so you are,’ he said, displaying no surprise. ‘You see? I’ve saved you a trip to the North.’

‘Well no, in fact there are a number of other—’

‘And how do you find the Celtic Tiger?’

‘It’s beautiful,’ Perdita said.

‘It’s rich,’ he corrected. ‘And it’s a miracle, considering the poverty and apathy of this country in the recent past. I would advise you, however, to give the suburbs a miss.’ Perdita thought of the house in Parnell Square and said nothing. ‘But then,’ he qualified himself, ‘there are no miracles. Listen to me talking as if I were already a united Irishman!’ He paused, as if waiting for her to comment but Perdita had no comment to make. ‘No miracles. Only grants. Lovely grants from the European Union.’ He smiled.

‘Well, and you have the peace dividend,’ Perdita reminded him.

‘Indeed,’ said Frazer. ‘So we have.’

Perdita’s spirits were lifting. Ian Frazer was one of the North’s most powerful industrialists, his name synonymous with everything energetic and optimistic about the expanding economy of Northern Ireland. She had not known what to expect, but certainly not someone as approachable as this. If she could persuade him to be one of the major contributors to her film, perhaps the project would not turn out to be as bland as she had feared.

‘Ms Burn!’ The young receptionist came hurrying up. ‘Oh, Ms Burn, there’s me paging the conference room and you sitting here right under my own nose. I couldn’t see you for the flowers!’

‘Hello,’ said Perdita. ‘What’s up?’

‘Jesus, would you ever forgive me? I told her there was no reply and she’s just rung off.’

‘Who?’

‘That Mrs Fionnuala James you were desperate to hear from? She just called you!’

‘Ah.’ In the split second that Perdita cursed the open charm of the Irish, she caught the tightening of muscles in Ian Frazer’s face.

‘Will you not phone straight back?’ the young woman persisted. ‘She’s only just this moment gone.’

‘Thanks. In a while, yes. Please don’t worry about it,’ Perdita said. The desk clerk retreated, looking puzzled. Ian Frazer was examining Perdita closely. Fortunately, at that moment the waiter brought tea.

‘What exactly is your film about?’ he asked when the waiter had gone. The tone was affable enough but the humour had left him. Perdita gave him the standard line she had rattled off several times that day. He appeared to be listening; asked questions. Perdita relaxed. Perhaps the name Fionnuala James meant nothing to him, after all. She felt too tired to hold in advance the meeting with him scheduled for later in the week. Anxious to recapture the informality of their first encounter, she asked him his impressions of Tweed Awareness Week.

They were both laughing at his account of a visit to a mill near Kilkenny when he asked abruptly, ‘And what’s the Sinn Féin line on Tweed? Do they plan any… publicity stunts?’

‘Oh—’ She had been preparing her answer. ‘That call.’ She waved her hand towards the reception desk. ‘It’s unconnected. An errand for a colleague back home.’

‘Really?’

‘Getting through to them. You know. When you have an English voice?’ She shrugged. She was not doing this well. ‘It’s like an imperial court. Impenetrable.’

‘It must be important, then, for Mrs James to call you back.’

‘Yes.’

‘My dear Mrs Burn. Perdita. I can see Mrs James is of far more interest to you than I am. Please don’t let me detain you.’

‘No. I mean, she isn’t. She can wait.’

‘She won’t wait. Mrs James waits for no one. Certainly not for someone with an English accent—unless, of course, she is leaving a bomb under their car. Your colleague did tell you about her background, I hope?’

‘I—I know that a long time ago she was wanted—’

‘Let’s not pussyfoot around. She was a terrorist. She has never been brought to justice. It may seem romantic from your side of the water; less so from ours.’

Perdita suddenly felt exhausted. ‘Mrs James is the publicity officer for Sinn Féin. Sinn Féin is a legal organisation and I have an errand for her office on behalf of a colleague in London. I have not met her. I’m grateful for your views, but I am not concerned with her past. Now, Mr Frazer, will you please have some more tea!’