7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Children's Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

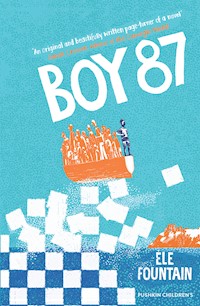

The story of a refugee: one child's journey stands for the journeys of many and the hopes of even more Shif is just an ordinary boy who likes chess, maths and racing his best friend home from school. But one day, soldiers with guns come to his door - and he knows that he is no longer safe. Shif is forced to leave his mother and little sister, and embark on a dangerous journey; a journey through imprisonment and escape, new lands and strange voices, and a perilous crossing by land and sea. He will encounter cruelty and kindness; he will become separated from the people he loves. Boy 87 is a gripping, uplifting tale of one boy's struggle for survival; it echoes the story of young people all over the world today. Ele Fountain worked as an Editor in children's publishing, where she was responsible for launching and nurturing the careers of many prize-winning and best-selling authors including Angie Sage, Philip Reeve and Sarah Crossan. She lived in Addis Ababa for several years, where she was inspired to write Boy 87, her debut novel. Ele now lives in what she describes as a 'not quite falling down house' in Hampshire with her husband and two young daughters.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

For Lily and Scarlet

When it was dark, you always carried the sun in your hand for me

Sean O’Casey, Red Roses for Me

Boat

Cold salty water stings my eyes and soaks my T-shirt. I cling to the clammy wooden edge of the boat as a huge wave swells towards me. The boat tips and I gasp as people slide against me and the air is pressed from my chest.

The sky is turning from light to dark grey; white foam tops the waves. The wind pushes relentlessly against my face, and with the next rolling wave the boat dips so low that buckets of water gush in over the side, soaking me again with freezing water. I feel it creeping above my ankles. No one cries out. Even the baby strapped to the mother beside me is quiet.

Green-grey waves make a wall around us. We rise to the top of another but there is nothing to see except spray blowing like rain in the icy wind. Europe is sprawled somewhere in front of us but I can’t see land. As we slide into the trough, more water rushes over the side of the boat. It is up to my knees. My feet are numb but I can tell that my shoes are heavy with water. I look up again and see a swirling wave bigger than the others rolling towards us in fury. The boat tips. This time we keep on tipping. The boat is full of water so it doesn’t roll up on the wave—it rolls into it, and the wave crashes over us like we are on the shore, only we’re in the middle of the sea. I hear screaming and then nothing as water rushes over my head.

I can’t tell which way is up to sky and wind, and which way is down towards the metres of sea beneath. I open my eyes and they sting but show me nothing more than cloudy bubbling water and the legs of someone just out of reach. I kick up once, my chest burning. I kick up again, knowing that in a second I can no longer fight the desperate urge to breathe in. I kick one last time, my legs tingling. I am about to black out just as wind blasts my face; I suck in air and some spray.

Choking, I pant and gasp; the currents tug me left and right as the swell lifts me up and down. I cannot swim but instinct makes me kick my feet to stay afloat. The shoes my mother bought with three weeks’ wages are so heavy I try to push them off without going under. I know I can’t kick water for long. Already my thighs and arms feel tired. I see four, maybe five, other heads swirling in the waves. How can three hundred people disappear so quickly?

A yellow plastic bag washes towards me. There are clothes inside. The knot has been tied tightly so that the bag is like a floating pocket of air. I cling to it.

A boy appears next to me, bobbing up from under the waves like I did seconds before. I reach out my hand to him. He looks at me. His eyes are big and oval-shaped and he reminds me of Bini. My best friend at home. I reach my hand out to him again and he tries to grab it but instead sinks beneath the waves. He doesn’t come back up.

Who will come to save me? Who knows where I am apart from the others tossing and bobbing in the waves like me? What would Bini do now?

BEFORE

Best Friend

“The square root can also be written as a fractional exponent.”

“Yes, Bini. Next time raise your hand first.”

I am pretty smart, but Bini is smarter. I can’t tell if our maths teacher is proud of us or just irritated by us. Maybe both. We know as much as he does now. Ato Hayat keeps a university textbook in his drawer and copies homework questions for us from it. It came with a sheet of answers, and it’s fine if we get the solutions right, but if we get them wrong he snaps at us that knowledge is a gift and we should study harder. He doesn’t understand the questions or the answers.

I’m going to be an engineer. Bini has wanted to be a doctor for as long as I can remember. When we were really small he would make me lie on the floor so that he could listen to my heart beating, or my liver—he wasn’t quite sure back then. As we got older, he started asking random questions, like “Where does sweat come from?” Or “Why does your heart keep on beating and not just stop when you go to sleep?” I didn’t know the answers and I didn’t really care.

He would say, “Just think of all those things your body does which you don’t understand, but you want to go and learn about how to build a bridge.” Usually I’m not fast enough to think of a clever reply until it’s too late to sound clever any more. Saying “Yeah, but how would a doctor reach a patient if there was no bridge to drive over?” seems a bit lame twenty-four hours later. Still, we are best friends. Maybe because we like to argue with each other.

Normal Day

The school bell rings, and even though I’m only heading to the market we race to the gate.

“See if you can get there first for once, squirt,” Bini yells over his shoulder.

All the boys in our class were a similar height until summer term, then suddenly Bini was a bit taller and now his body can’t seem to stop shooting upwards. I fix my eyes on his back, dodging the other kids in their blue uniforms, hopping on and off the dusty kerb as I weave round bodies and jump clear of oncoming cars. I see the market up ahead. People and small piles of vegetables spill from the pavement onto the street. Next to some open sacks of cinnamon, Bini is leaning against a jacaranda tree, mouth closed, pretending that he isn’t out of breath even though I can see his chest heaving up and down.

“Not bad,” he smiles, “for a squirt.”

I punch him on his skinny arm.

We wander home beneath a solid blue sky, the hot sun baking everything it touches. Our houses are next door to each other. Square houses with flat roofs, in a low oblong terrace on the edge of the city. Inside there is no upstairs, just two rooms crammed with everything we need. We sleep, eat, cook and do homework in these two rooms. Quite often it feels like we spend so much time in each other’s houses we might as well just knock a big hole through the wall and put a door there. When I was seven we were going to move somewhere bigger, but then my father died and we had no more money—only what Mum earns mending and making clothes at the workshop two streets along.

I don’t remember Dad being ill. Apparently there was nothing the doctors could do. One day he went into hospital, and he never came back. Bini’s dad moved out at around the same time. He went to find a better job on the other side of the city. Our mums became very close. Mum says that money isn’t everything. We are lucky to have a roof over our heads and it doesn’t matter what that roof is made of or how big the house is underneath it. Sometimes I wish I had my own room, though.

We step round the little kids sitting on the kerb. Too young for school, but not too young to look after the five goats eating grass at the shady edge of the road.

Bini and I sprint the last few metres to our front doors. I hurry to the wooden cupboard in the corner of the living room, take out a faded red T-shirt and jeans and change out of my uniform.

Seconds later, I hear Bini knocking. How does he get changed so fast? Before I’ve properly opened the door, he pushes in, schoolbooks piled in his arms.

“Let’s get this done quickly, then we’ll have more time for me to beat you at chess.”

“Is time all you need? You should have said so before.”

The only gift I have from my father is the chess set which he made for my sixth birthday. The board is a tin tray and the pieces are carved out of wood—carved by him. It’s my most precious possession. Not least because chess is the one thing I can always beat Bini at and it drives him crazy. We will keep playing until one day he wins, and I will never be able to beat him again after that.

Something Weird

The next morning, Mum leaves before I do. Work is busy right now, which is good and bad. My little sister Lemlem whines as she is bundled out of the house. I hear Mum promising her something nice as the door clicks shut behind them.

Two minutes later, Bini knocks. I grab my bag and we walk down the road to school, Bini slowly, me at normal pace to keep up with his giraffe strides. As we get closer to school, the roads are wider and the houses bigger. We’re about to turn the final corner when Bini slows down.

An army truck is parked about a hundred metres from the school entrance. Four soldiers are sitting in the back, rifles on their knees, watching the schoolkids pass in front. I look ahead to the gates. No one is kicking a ball around outside. The other kids are filing into school without looking up. One mother turns around and starts walking back the other way, taking her sons with her.

“What’s going on?” I ask Bini.

“No idea,” he replies.

We keep quiet as we pass the truck.

Our first lesson is chemistry. Ato Dawit is my favourite teacher, but today I don’t enjoy the lesson. Ato Dawit seems tired. No one puts up their hand to answer questions.

At lunchtime Bini and I head for our normal spot over by the shady trees in the corner of the yard.

As we start to eat, I watch Kidane walk slowly in our direction with two of his friends. There isn’t any more space to sit down, so I wonder what he wants. My stomach does a little flip. Kidane had the same growth rush as Bini, only he grew wider as well as taller. Now he looks about four years older than the rest of our class. A class we have been moved up to only because of our good grades.

“Why is the army hanging around outside our school today?” asks Kidane.

“How should we know?” Bini answers.

“Perhaps you should go home and ask your dad.” He looks first at Bini, then at me.

Bini stares at him. “Why don’t you go and ask your dad? Or would you need to help him with a big word like army?”

Kidane grabs Bini by the collar of his school shirt. “At least mine hasn’t run away. It’s people like you and your dad who make it dangerous for the rest of us,” he hisses.

Bini stands up. Kidane is still holding his T-shirt, but now their eyes are level. Bini doesn’t flinch. Kidane shoves him backwards and walks away with his friends, glancing back to give us both a death stare.

My mouth feels dry when I speak. “What do you think he meant when he said we make it dangerous for the rest of them?”

Bini is frowning at the ground, deep in thought. “I don’t know, but I feel like everyone else does.”

“Have you heard anything from your dad?”

“No. He hasn’t sent Mum any money either. She says it takes time to find a job that earns enough. Six years seems long enough, though.”

“Kidane must know my dad died,” I say.

“He’s an idiot,” says Bini. “That’s one thing I am sure about.”

After school, we head home in silence, Bini kicking at stones. I almost feel like letting him win at chess, but decide he’ll feel better in the morning anyway. Instead I let him reach check.

Police

As dusk approaches, Bini heads home for dinner. Mum and Lemlem still aren’t back. This means Mum is finishing a big order. Maybe a wedding dress or something for a government official. Lemlem won’t start school for another year so she spends most days, or at least part of the day, at the tailor’s too—playing in the offcuts, helping to fold fabric and pick cotton from the floor.

My stomach growls, but there is no bag of injera hanging from the cupboard door ready for dinner. I know that nearly everywhere will have sold out of it by now. The tsebhi won’t be enough on its own.

I’m not supposed to leave the house after dark. I count to twenty, but there’s still no sound of footsteps approaching, so I decide that dusk doesn’t count and take five nakfa from the old milk powder tin.

I head down the empty road to the nearest shop. The light is still on.

“Kemay amsikum, Solomon,” I call.

He stops putting tins on the shelf and turns around. “Kemay amsika.”

I point to the flat round basket on the counter containing whatever injera is left. Two pieces. Solomon takes my coins and stuffs the injera in a bag.

The sudden rumble of a vehicle approaching on the road behind startles me. There is hardly ever much traffic after dark, especially out of the city centre. I turn but am momentarily blind to the dark road, an imprint of the shop’s light bulb still white in my eyes. I see an army truck and the silhouette of three soldiers with rifles jumping down from the back. Their heavy boots crunch in the sandy gravel of the road. I turn quickly back to the bright shop, not wanting to attract attention. I hear one of the soldiers knock on the door of a house next to the truck. The other two are at a house two or three doors further away.

I take the bag of injera and walk back in the direction of my house.

I hear raised voice from inside one of the houses, then a second deep voice shouting, “Hey. Hey!”

I instinctively know this shout is directed at me. I haven’t done anything wrong, but everyone avoids the military. I break into a run, skidding as I turn the corner to my street. I can hear heavy boots crunching quickly down the road I just turned off. I fumble for a key in the fabric folds of my pocket. Using two hands I guide it into the lock, stumble inside, then push the green metal door back to click shut as quietly as my sweaty hands will allow.

I sit very still. I realize that I’m holding my breath, and try not to pant. Each breath seems like a betrayal. Outside the door it is silent.

I’m not sure how long I sit like this. Perhaps twenty minutes later, there is a muffled thud as the front door eases open. I freeze. Then my mother’s voice filters through the panic.

“Shif, what are you doing sitting there in the dark? What happened?”

Lemlem runs over and hugs my knee. “What happened?” she mimics my mother.