Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

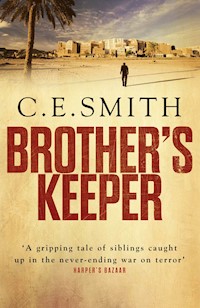

Struck off and hooked on prescription pills, disgraced American surgeon Ryan Burkett flies to the war-torn Middle East to identify his murdered twin's body. Staring down at the lifeless form in the mortuary, it is as though Burkett is gazing at his own failings. His brother was first and best - the better athlete, better doctor, better son. With little reason to go home, Burkett agrees to take over his brother's charitable surgical clinic. Within weeks, however, he is taken hostage by Islamic fundamentalists. Forced into withdrawal - from both drugs and his own self-loathing - Burkett becomes convinced that his captors are his brother's murderers, and that revenge may be the only path to redemption.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Born and raised in Atlanta, Georgia, C. E. Smith studied English at Stanford and medicine at Vanderbilt. In 2013, he won Shakespeare & Company’s international Paris Literary Prize. He lives with his wife and children in Nashville, Tennessee. Brother’s Keeper is his first novel.

Brother’s Keeper

C. E. Smith

ATLANTIC BOOKS

London

Copyright page

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2015 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © C. E. Smith, 2015

The moral right of C. E. Smith to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78239 425 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78239 426 6

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Dedication

For Brooke

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

Acknowledgements

1

The squawking radio, some kind of prayer, is torture to Burkett’s headache. The driver speaks no English, or so it seems when Burkett asks him to lower the volume. He’d lower it himself, sacrilege or no, but a wire partition confines him to the back of the cab.

They’re next in line at a military checkpoint, where a one-armed man with the dark skin of a native Khandari endures a painstaking search despite his advanced age. The old man watches impassively as the soldiers, in flagrant disregard for the standstill traffic, mount his wooden flatbed and jostle the sisal bales and overcrowded birdcages. It could be the missing arm that aroused their suspicion: he could have blown it off making bombs.

Whatever the case, their scrutiny doesn’t bode well for Burkett, even if he just cleared customs without a problem, and even if most of the drugs he’s carrying are perfectly legal. Of the hundred or so packages of antibiotics, he’ll simply repeat what he said less than an hour ago at the airport: these medicines have been donated to the people of Khandaros, to a clinic that treats the poor free of charge.

But his personal stash of Xanax and Valium, a week’s worth, could earn him up to ten years in prison. A week for ten years: it seems on the surface like the risk of a madman, but only a pharmacist or a certain type of addict would notice the discrepancies of pills and labels. At least that’s what he’s been telling himself in the days since his summons to this impoverished island.

The drug laws here are rather harsh for a new democracy boasting social reform: life in prison for a kilogram of marijuana, death for five grams of heroin. In some ways, nothing has changed since the draconian years of Quadri the Behemoth. It is well and good to disband the secret police, to hold fair trials and rock concerts, but to Burkett’s way of thinking, the concept of westernization isn’t complete without some degree of permissiveness in the area of pharmacology.

But he isn’t worried. The customs inspector at the airport hardly bothered with his shaving kit, much less any pills inside. Why should he expect any different from troops at a checkpoint? They have more important things to consider, like their fledgling government’s war with Islamic militants. They wouldn’t waste their time on minimally addictive drugs when a suicide bomber could be sitting in the very next car.

The driver shuts off the radio as he pulls up to the checkpoint. Burkett welcomes the silence, though in a way it grants the soldiers a measure of respect he isn’t sure they deserve. There are signs of poor discipline: an unsnapped holster, a missed belt loop, even food stains on the taller one’s shirt. Burkett doubts he’d concern himself with such superficial details if the two men weren’t armed with assault rifles.

‘Salam,’ the taller one says, studying Burkett. ‘Passport, please.’

Burkett hands his passport through the window. He waits while the soldier confers with someone in a parked SUV. He hears the word ‘American’ and the SUV’s door opens. This one is older, more professional in his bearing. A member of the old guard, Burkett guesses, maybe a player in the coup nearly twenty years ago that brought an end to the ancient line of kings and paved the way for Quadri.

The older officer flicks through Burkett’s passport. He reads the name aloud – Ryan as ‘Ron’, Burkett as ‘Buckett’ – and lifts his sunglasses for a closer look at the picture, which shows Burkett in the goatee he wore during medical school.

‘What is your profession, sir?’

‘I’m a surgeon,’ Burkett says, which draws a look of confusion. ‘A doctor,’ he says. ‘But I’m here for personal reasons.’

In the heat Burkett wants to follow the driver’s lead and get out of the cab, but the soldier blocks the door while trying to compare the passport photograph to the real thing. He takes much longer than necessary, perhaps because of the goatee, and eventually shakes his head as though resigned to the impossibility of verification.

‘Why empty?’ he asks, thumbing through the pages.

Perhaps he thinks the new passport is fake. The single stamp represents his first international trip in years.

‘I haven’t had much time for travel,’ Burkett says. How could he explain more than a decade of surgical training at less than minimum wage?

The soldier slides the passport into his shirt pocket. He yawns and mutters something to the cab driver, who reaches through the window and pops the trunk.

Burkett gets out to watch while his luggage is searched for the second time today. The soldier lifts the shaving kit by its strap, the pills inside faintly rattling, but sets it aside in favor of a stethoscope. Holding it up he grins and says, ‘Doctor surgeon’, as if only now comprehending Burkett’s profession.

He opens the duffel of antibiotics and begins shuffling through the boxes as if looking for a particular label. If he had such difficulty with the word ‘doctor’, what could he possibly learn from a pharmaceutical box? He opens a package and draws out a plastic card with rows of tablets in transparent domes. He squints at the words on the peel-away back.

‘Ciprofloxacin,’ Burkett says.

Apparently satisfied that Burkett isn’t smuggling narcotics, the soldier moves on to the other duffel, which produces a froth of mosquito netting as he pulls back the zipper.

‘What is this?’ the man asks.

Mosquito netting works just as well, if not better, than the expensive mesh surgeons typically use for repairing hernias. Burkett makes cutting gestures and points to his groin, but the soldier has lost interest. He’s found something else buried in the duffel. His hands emerge from the white folds with a bottle of bourbon.

‘This for surgery too?’ the officer asks. Is he making a joke?

‘Duty free,’ Burkett says. ‘Do you understand duty free?’

The officer rotates the bottle, appraising the label.

‘Do you understand the prison?’ he asks.

Burkett remains silent. He’d gathered online that the ban on alcohol applied only in name, and almost never to foreigners or non-Muslims. The customs agent at the airport was so preoccupied with the antibiotics and their expiration dates that he hardly seemed to notice the bourbon. Or rather he noticed but chose to avoid the paperwork of reporting it.

‘Pardon me,’ the officer says, and carries the duffel to the SUV. When he returns with the bag, Burkett can tell from the lighter weight that his duty free bourbon has been confiscated.

‘Can I have my passport?’ Burkett asks.

‘There is a fine for liquor,’ he replies, fanning himself with Burkett’s passport. ‘The fine is one hundred dollars American.’

The cab deposits him at a crowded intersection supposedly in the vicinity of the medical complex. He unfolds a map but without knowing the street names he can’t even be sure of his own location. In the niche of a doorway, he sets down his luggage and sorts through his backpack. Both of his flasks are empty and yet he finds himself unscrewing the caps and hoping a drop might fall on his parched tongue. From his shaving kit he takes two pills, swallowing them dry.

A boy sits in the shade with a pair of wooden crutches that look like Victorian relics except for the armpit cushions of duct tape and foam. At the sight of Burkett the boy, whose left leg is encased in plaster, extends his open hand. Burkett offers a five-dollar bill, which the boy receives in silence.

In the cab he had only limited success with his Arabic–English dictionary, but again he opens it and speaks the words for ‘hospital’ and ‘morgue’. The boy says something and points in the direction of a cylindrical tower that stands out for its height as well as its covering of elaborate fretwork.

To reach it Burkett has to navigate a warren of crowded alleys and side streets congested with stalled traffic. A welter of humanity fills the courtyard outside the building, no doubt the encamped families and friends of patients. Women in burqas sell food and bottled drinks from an old refrigerator turned on its back. A group of elder Khandaris with seashells in their beards stand around a brazier and glare at the passing white man. Children gather around him, a swarm of brushing hands.

He crosses an ambulance bay and enters the hospital through sliding glass doors. He pauses at a security desk, expecting to be questioned, but the uniformed guard merely smiles and nods. In the crowded waiting area he checks his pockets and realizes his smartphone has been stolen, probably by the urchins in the courtyard. There is no way of knowing. He glances toward the security desk but there’s no point. At least his phone was password protected. At least he still has the disposable he purchased at the airport.

Patients lie on beds parked in the hallway, leaving little room to pass. He tries to keep his luggage from bumping the bedrails and IV catheters. A frail jaundiced woman reaches for him, and he feels a chill at the touch of her fingers. He searches her face for some hint as to the meaning of her feverish muttering, but her eyes suggest delirium.

‘I’m sorry,’ he says. ‘I don’t understand.’

Many of the signs have English translations, so he’s able to find an information desk manned by another security guard. On the wall hangs a photograph of President Djohar, the self-proclaimed reformer who came to power in this island nation’s first free and fair election. One of his earliest duties as president was to supervise the hanging of his predecessor, but the televised event became an embarrassment when the gallows fractured under the Behemoth’s weight. Burkett wonders if this was the hospital where the former dictator languished for months in a coma before his eventual death obviated the need for a second hanging.

The security guard’s irritated look softens when Burkett asks for the morgue. Mumbling into his shoulder radio, the guard escorts him to the elevator. They descend two floors and pass through an abandoned ward where empty patient rooms form a circumference around the nursing station. They take a staircase down yet another level, and in a subterranean corridor Burkett has to stoop to keep from bumping the rusted, antiquated pipes, which in some cases are suspended by frayed rope.

They come to a metal door with an intercom. The guard holds down the button, producing a buzz so muffled as to seem buried. From down the hall comes an elderly physician in a white coat stained with what looks like blood. His expression of surprise makes Burkett wonder if he heard the buzzer at all. The guard speaks into his walkie-talkie and turns down the dim passage, ignoring Burkett’s thanks.

The physician puts on his glasses for a better look at the American. Recognition passes over his face: he knows why Burkett is here.

‘I am Dr Abdullah, chief of pathology,’ he says.

The doctor waves his name-badge over a sensor, the metal door unlatches, and Burkett follows him into an anteroom where shelves are stacked with protective gowns, gloves, and masks. At the doctor’s urging, Burkett leaves his bags, but he’s reluctant to set them on the floor, this being a morgue, so he hangs his backpack from one of the hooks and props his two duffels in a chair.

They put on rubber gloves and surgical caps and walk through an autopsy suite, where three cadavers lie covered on stainless steel tables. One of the heads is exposed, a man in his forties or fifties with a full beard and ligature marks on the neck.

The next chamber is lined with freezer doors. After checking a handwritten chart on the wall, the doctor pulls open one of the freezers. He slides out a body bag on a tray. He unzips the bag, exposing a face identical to Burkett’s except for the pallor and bruising. The doctor brings over a metal folding chair but Burkett refuses to sit down.

‘Show me,’ he says, waving a hand over the body.

‘Are you sure?’ the doctor asks.

Burkett doesn’t need to reply. The doctor pulls down the zipper. There are incisions from shoulders to pubis, stitched with twine. Two gunshot wounds to the chest, no visible powder burns. Burkett turns the body on its side looking for the exit wounds, but there are none.

The doctor holds up a finger and mumbles, ‘Pardon,’ and disappears through a door.

Burkett can make out the knot in the left clavicle – an old wrestling injury from their time at Penn State. His brother became something of a legend for winning the national championship despite having sustained that fracture during the second period of the final match. Of the twins Owen was always the better wrestler. He was a better surgeon, too.

There are contusions on the right hand, and when Burkett lifts it he feels the shifting fragments of bone: a boxer’s fracture, which means Owen must have hit someone very hard.

The pathologist returns with the bullets, amorphous lumps of metal in separate plastic bags.

‘Kalashnikov,’ the doctor says.

He conducts Burkett into a small windowless office cluttered with textbooks and journals, the walls adorned with diplomas. On the desk Burkett recognizes a recent issue of The Lancet. It is an office no different from those he might have found in the department of surgery back at Emory.

Burkett signs a series of documents, most of them in English. He’s given copies of the autopsy report, death certificate, and – the doctor nearly forgot – a large manila envelope containing the items found on the body: wallet, keys, belt, a pocket notepad, and a cross on a lanyard. Right away he sees that something is missing.

‘He wore a silver ring,’ Burkett says.

Dr Abdullah gives an apologetic shrug and says, ‘There was nothing else.’ He absently pats his pockets, which seems for a moment like grounds for suspicion, but it turns out he’s only looking for another pen.

‘I understand from the embassy that you would prefer cremation,’ the doctor says.

‘That’s right,’ Burkett replies. ‘It’s what he wanted.’

‘I see.’

‘Is there a problem?’

‘No,’ he says, smiling. ‘We have a – what is the word? Oven?’

‘Crematorium?’

He nods. ‘Crematorium. Yes, this is forbidden by Islam, but the natives do request it.’ He shrugs. ‘The graveyards are filling up, so to speak, and very expensive.’

2

On the ground floor of Burkett’s hotel is a bistro frequented by journalists and aid workers. Sandbags and poured concrete shut out the midday sun. He doesn’t mind: when drinking he prefers an atmosphere of perpetual twilight. No alcohol on the menu, but the waiter, who seems hardly surprised by Burkett’s order, serves him bourbon in a porcelain teacup.

His brother’s notepad bears signs of long hours in a back pocket – sweat stains, crushed rings, the pages molded in a vaguely gluteal curve. Burkett pages through the lists of drugs and medical supplies, trying to see something of his brother in the handwriting, the minuscule letters that look like claw prints. He reads the list of items necessary for a lumbar puncture, the differential diagnosis for optic neuritis. There are occasional verses and snippets of prayer.

Grant me the words to pray as You’d have me pray.

When Nick Lorie arrives, half an hour late, Burkett’s on his third bourbon but not as drunk as he’d like.

‘Welcome to the Rock,’ Nick says as they shake hands.

A former Navy Seal, Nick bears little resemblance to the soldier Burkett envisioned from their correspondence. He has a beard and mussed hair, and he’s shorter than Burkett. Tattoos cover his forearms – geometric patterns, cross thatch grids or jagged lines in parallel – but none of it, as far as Burkett can tell, suggests any kind of military affiliation.

‘I brought some of Owen’s things,’ Lorie says, placing a wrinkled paper bag on the table.

Burkett glances inside: a stethoscope, sunglasses, a pharmacopeia, two novels, a deck of cards, and a photo album. A picture in a frame: the two of them in the days of college wrestling. It’s getting to the point that he might need another suitcase for his brother’s effects.

‘Did he not have a phone?’ Burkett asks. ‘Or a laptop?’

‘Taken,’ Nick says. ‘Along with the car he was driving.’

‘He used to wear a Celtic-style ring on his index finger. It had an inscription inside.’

‘I remember it. It must have been stolen as well.’

‘I never thought of Islamic militants as thieves.’

Nick’s gaze lingers on Burkett’s teacup. Perhaps he’s a teetotaler like Owen. Bourbon could easily pass for tea, especially in this dim light, but the cup seems to make Nick uncomfortable. Perhaps he fears someone might see it and mistake him for a drinker. Burkett pulls it closer to himself.

‘How was your flight?’ Nick says. ‘You came through Frankfurt, right?’

‘And New York before that,’ Burkett says. ‘I got in yesterday.’

Nick speaks to the waiter in Arabic. Burkett finds this impressive, but Nick insists that anyone would know a language after ten years. Besides, the dialect isn’t much use anywhere else.

‘Ten years is a long time,’ Burkett says.

‘We love it here,’ he replies with a shrug. ‘This is our home now.’

He and his wife Beth hadn’t planned on staying this long. It was meant to be a one-month trip, a temporary medical clinic, but they decided to stay.

‘The Lord wanted us here.’

These words are jarring to Burkett. It’s the kind of language he might expect from his brother’s journal, but not in conversation with a stranger. Could this be the way he spoke with Owen? They were close friends, after all. Perhaps Nick has to remind himself, moment to moment, that this man with Owen’s face is in fact someone else.

Nick looks at the duffels as if noticing them for the first time.

‘Supplies for the clinic,’ Burkett says. ‘Antibiotics, mosquito netting – some of the things Owen said you needed.’

He’d carried the drugs for months in the trunk of his car, planning to send them to his brother by mail. They were given to him by a sales representative from the pharmaceutical company, a woman he used to sleep with. The mosquito netting he bought the day before his flight at an army surplus store.

‘We’re always in need,’ Nick says. ‘I can’t thank you enough.’

‘I’m happy to send more,’ he says.

‘Why don’t you stay on and work with us?’ Nick says, and off Burkett’s smile adds, ‘I’m serious. We pay for a mobile operating room twice a week, but without Owen it’s sitting empty. If you had the slightest inclination . . .’

‘I don’t share my brother’s religious convictions,’ Burkett says.

‘You’d be working as a surgeon, not a missionary. International Medical Outreach would pay you a stipend, along with your travel expenses. You’d have free room and board.’

‘After what happened to Owen . . .’

‘Look, it’s obviously dangerous, but Owen – that was a fluke.’

‘Aren’t you worried about the political situation?’

‘If things get hairy, my friend Mark Rich, an American army officer, has guaranteed seats for us on the first helicopter out.’

‘I didn’t think there were American troops here.’

‘He’s an advisor for Djohar’s drone program,’ Nick says.

Burkett shakes his head, smiling to soften what he says next: ‘I could never live in this place.’

‘I can’t begin to describe the difference you’d make.’

‘I’m sorry,’ he says.

But there’s a certain appeal in the idea of walking away from his life in the States: his medical school debt, the latest drunk-driving conviction, and his embarrassing dismissal from the fellowship program at Emory. Would it even be possible? He can’t help but wonder if the clinic stocks benzodiazepines. He could stretch the supply in his shaving kit two weeks. He has an arrangement with another physician in Atlanta, a kind of prescription exchange, but that wouldn’t do him much good overseas. How long would he stay? A month, a year? But the question is moot: he’s already signed a contract with a surgical practice in Atlanta.

‘Let me show you the clinic,’ Nick says, opening his laptop. He uses Burkett’s room number to access the hotel’s wireless service. He pulls up the IMO website and clicks past the memorial to Owen – the short biography that neither confirms nor denies the real nature of his work here – to a map that fills his screen: an island shaped like a dagger, with its blade-like flatlands to the north, and the southern half whose mountainous topography suggests the nubs of a grip. He zooms in on the north, prompting an overlay of colored roads and labeled towns.

‘Here’s Mejidi-al-Alam,’ he says, pointing and then expanding the image till the scant buildings and roads are visible as tiny squares and lines. Colored graphics highlight a cluster of buildings, the medical clinic.

‘How far are you from the coast?’ Burkett asks.

‘About an hour’s drive.’

He shakes his head. It seems fitting that his brother would travel halfway around the world only to deny himself an ocean view.

A couple sits down at the next table – an Arab in western garb, and a white woman who speaks English with a French accent. He gathers from their tone that they’re colleagues. A purely professional relationship, he thinks, as he steals another glance at the woman. From the Arab’s camera bag, Burkett decides they must be journalists.

Nick magnifies the vicinity of the clinic. He points out the nearby military outpost, separated from the clinic by a tributary of some kind.

‘Show me where they found him,’ Burkett says.

The cartoon hand follows an unnamed road till there is nothing on the map except for the road. And when Nick switches to the satellite view, the background wrinkles into a brownish landscape of rock and shadow. The last thing Owen saw must have been stone and sand. Some desert hell.

‘He was on his way home,’ Nick says.

‘Was he set up?’ Burkett says. ‘Was it the patient he visited?’

Nick doesn’t know much more than Burkett – only what he’s gleaned from the newspaper accounts. The national police have repeatedly emphasized their commitment to the case by specifying the number of officers involved at each stage: three interviewed Owen’s last patient, ten scoured the scene for clues.

What kind of clues? What would a clue possibly signify? He pictures some functionary crawling around with a magnifying glass. What are the odds of an arrest or punishment? The culprits are known already – they’ve taken credit, claimed responsibility. Heroes of Jihad, they call themselves. Does it even matter which of them pulled the trigger? Of course Burkett would like to find him. He’s probably young, educated in some madrassa, if at all.

When he gets back to his room, he empties the brown paper bag on the bed. The deck of cards, creased and dogeared, is held together by a rubber band. He should have recognized it sooner, what with the swimsuit models on the backs of the cards. He flips to the ten of hearts, the one they liked best, the one they called Lydia – a beautiful brunette with her back to the camera, her face in profile. The inflated 1980s hairstyle dates the picture as much as the sepia tint. At Penn State, Burkett and his brother used these cards to guide their push-ups. They would shuffle the deck and work their way through, counting the face cards and aces as twenty each.

The framed photograph shows the two of them at the NCAA wrestling tournament – Owen’s arm in a sling, the first-place medal dangling from his neck. Burkett’s expression in the picture conceals his own anger at not placing. How he’d hated his brother that night – not just for winning, but for the injury, which only enhanced his glory. Why would Owen have kept this particular photograph? Perhaps it summarizes their relationship: Owen with the championship medal, Burkett with nothing but bitterness. He rubs his thumb against the glass, as if to palpate a barrier he imagines between the two wrestlers.

Still annoyed by the confiscation of his bourbon, Burkett negotiates with the concierge for another bottle from the hotel’s stock. The concierge demands fifty dollars – added expense to cover the risk of losing his job or running afoul of the Ministry of Vice. Burkett takes out his wallet. At this rate, his supply of cash won’t last the weekend.

‘If you like,’ says the concierge, ‘I can give you something stronger.’

He conducts Burkett through a large kitchen, down a back stairwell and into the basement. The man looks both ways before unlocking a closet and pulling the cord inside to light a bare bulb. He kneels and slides out a cooler and opens the lid to reveal stacks of clear plastic bottles. He glances up at Burkett.

‘Siddique, my friend.’

‘How do I know this won’t make me blind?’

‘Please,’ he says, ‘this is the highest quality.’

To prove it he unscrews one of the caps and sips. He winces at the taste.

‘See, no problem.’

‘How much?’

‘For you, ten dollars per bottle.’

‘I’ll take five,’ he says. ‘And the bottle of bourbon, too.’

Back in his room he tastes the siddique – a burning pleasure, but without the sweetness of bourbon. A useful substitute, he thinks, for drinking when already drunk, when his taste buds are numb. He unscrews the new bottle of bourbon and fills his two flasks, catching the run-off in a plastic cup. He takes two Xanax and lies down with the cup and bottle.

He wonders if he has grieved enough for his brother. Does he owe it to him to shed tears? If there were some kind of duty to grieve, surely Burkett would fall short of the obligation. What he feels more than grief is guilt for his grief’s inadequacy.

Another pill to help him sleep, to help him stop thinking like this. Perhaps this is the very character of grief, that it can’t be separated from its shadow, that the aggrieved must also ponder the idea of grief. How much simpler grief would be if left alone – if he could experience it without thinking about it. Are other emotions like this? Does happiness demand an account of itself?

He calls it grief, but grief was what he felt as a boy of ten when his mother died. His brother has left him with an emptiness – a piece of himself gone. No, not a piece. This is not the same as an amputated limb. The loss is more diffuse, more complete, but at the same time more subtle. As if the absence represented a tiny portion not of himself but of every cell, every atom in his body.

‘Owen.’ He mumbles the name as if speaking directly to his brother – as if his brother were a casual presence here in the room. But the name seems out of place – like a familiar word in the wrong context. Names are words whose meanings can suddenly change. It was rare that he and his brother actually called each other by name. He turns on the bedside lamp and opens his brother’s notepad to a random page. The jagged, minuscule handwriting is so similar to his own – perhaps indistinguishable. The medical notes could easily have been written by either of them, but then there are the strange religious jottings:

For what is your life? It is even a vapor that appears for a short time and then vanishes away.

Probably a Bible verse, it brings to mind yet again the question of an afterlife. Beliefs that came so easily as a child now seem absurd.

He thinks of that quirk of physics, where particles once linked but now separated continue acting as though linked no matter the distance between them. Strange interaction at a distance. What is the distance between him and his brother? If one particle is annihilated, shouldn’t the other one be annihilated as well?

There is no afterlife, he tells himself, as much as he might wish otherwise. But if a single particle can exist in two places at once, or if two can be linked across any distance, then perhaps life and death represent flickering states in a more permanent scheme. Perhaps somewhere else, in some kind of parallel universe, it is Burkett rather than his brother who is dead.

The body lies in a cardboard box and wears a white gown provided by the morgue. A Catholic priest lends an element of religious formality, but it’s Nick Lorie who prays and utters words of remembrance. Burkett and his brother were brought up Catholic – non-practicing, as they liked to say. The family’s religious affiliation only seemed to have relevance on holidays.

The way Burkett remembers it, he and his brother were alike in every way till Owen’s religious conversion. They were fifteen, at a Christian sports camp. Burkett was amazed when his brother responded to the altar call. Had they not heard the exact same sermon? Did they not have the same DNA, almost identical brains? God, if he existed, seemed to have chosen one brother over the other. How could his brother believe in a God who would make such a distinction?

He sees the conversion as the beginning of their separation – and also when Owen first chose the path that would culminate in his own death. If Owen had ignored that altar call perhaps the two of them would have ended up doing residency together and joining the same practice.

Burkett’s anger is large enough for Muslims and Christians alike. The pastor at the sports camp, Nick Lorie, and any other Christian who inspired Owen to risk his life. He could write a treatise on the evils of religion.

‘We thank you,’ Lorie says, ‘for the promise of eternal peace. Amen.’

The priest makes the sign of the cross. The orderly covers the box and pushes it on rollers into a stone furnace and bolts the cast iron door.

Burkett waits while the body burns. There is no smoke from the grate, no odor of burning flesh. The only evidence of fire is the heat radiating from the furnace. A barrier seems to surround him, a barrier composed of nothing but heat. He is cut off from the others, sealed in a thermal pocket all his own. They are separated from him by only a few feet, but it could be miles.

For the remains he’s given a cylindrical plastic container with a screw-on cap. Like Tupperware, he thinks, as he scoops ashes and bits of bone from the furnace. He wishes he’d thought to bring some kind of urn.

The wood-handled garden shovel seems clean enough, but he can’t help wondering how often it has been used for this very purpose. Are his brother’s ashes mingling with those of others? Does it even matter? He can taste the floating dust as he fills the container. The orderly is no doubt breathing it as well. To collect the last of it, the orderly produces a small broom and dustpan.

3

Burkett takes a shower and puts on fresh clothes and goes down to the bistro for another drink. He has no good reason for bringing his brother’s ashes with him. It just seems like a bad idea to leave them unattended. What if a housekeeper poured them down the drain? He sets the canister on the table and lifts his teacup. My brother the martyr.

He listens to the only other customers, a group of older men, Germans and Italians as far as he can tell, but speaking English. They are probably journalists. He counts six empty wine bottles, one for each man. He is sitting on the opposite side of the room, but they speak loud enough for him to hear.

‘Djohar is right,’ an Italian says, jabbing his smokeless pipe in the imagined direction of the Khandarian president. ‘Why should terrorists be appeased with a country of their own?’

The man beside him nods. ‘My question is this: if you give it to them, who can guarantee that the bombings would even stop?’

‘You rebuild the Khandarian Wall,’ says one of the Germans, his sarcasm clear despite the thick accent. ‘Simple, no problem.’

‘I agree, this is ridiculous,’ says the man with the pipe. ‘The separatists in parliament are always talking about the wall but none of them have any idea how to pay for it.’

The French woman he saw before enters the bistro and removes her coat. She wears a headscarf, but her sleeveless blouse and knee-length skirt are wildly audacious by local standards. The journalists, suddenly silent, acknowledge her with glances or outright stares. She takes a seat at a table near Burkett. She meets his eyes, quickly looks away, and after a moment looks again. It is the second glance that justifies his approach.

He senses malevolence in the journalists’ refusal to look at him. He resists gloating. After all, he’s the youngest man here by at least twenty years. He might look old for his age, now thirty-four, but he’s a picture of youth next to them.

The circumstances aren’t well suited to his usual strategy of sitting next to a woman without speaking.

‘Mind if I sit here?’

With her foot she slides out the closest chair. He sits down and places the canister of ashes in the chair beside him.

She asks, ‘Do you always bring Tupperware when you drink?’

‘Only on special occasions.’

‘Is this a special occasion?’

‘Maybe,’ he says. ‘Ask me again in ten minutes.’

It is the sort of idiotic banter he only uses with women in bars. Tonight he is more conscious of it, almost wincingly so, perhaps because of the presence of Owen. He can see his brother shaking his head and rolling his eyes – his brother who as far as he knows never drank a sip of alcohol, much less seduced a woman in a bar.

Does this actually work for you? Owen is asking. How can anyone take you seriously?

Véronique is her name. A journalist in her mid-thirties, she’s covered militant Islamic groups for more than a decade. It turns out she’s heard about what happened to Owen. She has a particular interest in the Heroes of Jihad, whom she sees as much more of a threat than the typical fanatics. It is because of the Heroes and their organized campaign of bombings that the public and many in parliament are seriously considering a referendum on the secession of South Khandaros.

‘Two years ago,’ she says, ‘there were literally hundreds of groups claiming responsibility for attacks in the capital. Now it is just the Heroes.’

‘How did that happen?’

‘You could say the jihadists had to pool their resources to fight their assorted enemies – warlords, the national army, you name it. Secularists, unionists, foreigners.’

‘Why did the Heroes rise to the top?’

‘Their leader, Mullah Bashir.’

‘Didn’t someone kill that guy?’

She nods. ‘Six months ago, probably a drone attack. It was a political victory for President Djohar, a strike against terrorism, but Bashir was loved by many, so his death served to inspire even greater hatred, especially against the west.’

‘Isn’t it amazing how drones always inspire hatred for Americans, even when those very drones are owned and operated by someone else?’

‘Americans are hated not just for selling drones to the regime, but also for sending missionaries to convert Muslims, for exporting pornography and fast food. For being the great Satan.’

He stares at the ashes in the chair beside him. ‘The group that funded my brother’s clinic, International Medical Outreach, claims he wasn’t here as a missionary but as a health worker.’

‘To say otherwise would endanger those working at his clinic. It is illegal here to preach Christianity. What your brother was doing was akin to espionage. A foreigner doing illegal work under a pretext. Medicine was his cover, so to speak.’

‘What a waste,’ he says.

She shrugs. ‘Do you disapprove of your brother’s proselytism?’

‘You can’t expect to come to a place like this and impose your beliefs on others. It’s certainly not worth dying for.’

‘By law, if a Muslim converts to Christianity, he forfeits all of his property. Missionaries should consider this when they come here with their religion.’

‘I thought there was a new constitution,’ he says. ‘I thought it was approved by western monitors.’

‘Have you read the new constitution?’ She pauses, but he doesn’t think she’s waiting for a reply. ‘The law against apostasy was one of many concessions to conservatives in parliament.’

‘What about the tribal religion?’ he asks. ‘Do the Islamists hate it as much as Christianity?’

‘Samakism,’ she says. ‘There are not many actual practitioners, not enough to have any real influence.’

‘What exactly do they believe?’

‘There was a powerful being,’ she says, ‘a Jinn, who created this island, El-Khandar, by dropping a great jewel into the sea. To protect the islanders, the Jinn sent a demigod, a one-eyed shark named Samakersh. You occasionally see his symbol on doors and buildings.’

She uncaps a pen and on her napkin sketches an eye, a simple oval with a dot near the center, and beneath the eye a jagged line like the edge of a saw. An eye floating over mountains? Not mountains, he realizes, but teeth – the teeth of a shark.

Though she hasn’t yet finished her wine, he gestures for the waiter to bring another round. She has a kind of dark-eyed beauty, but what he finds most alluring is her voice – not just her raspy eloquence or French accent, but the odd formality of her language, her reluctance to use contractions.

‘How do you feel about Djohar’s use of drones?’ she asks.

If Burkett were honest he’d place his opinion on drones somewhere between apathy and disapproval. But what does he really know about it? He imagines soldiers with joysticks, a disturbing overlap of gaming and killing.

‘He has no choice,’ Burkett says. ‘He lacks the manpower to keep his country from falling apart.’

‘There has been an outcry over civilian casualties, particularly from America, where private companies are selling him the drones in the first place. But you are right, what choice does he have? How else can he deal with the unofficial mini-state in the south, people paying tax to a separate Islamic regime?’

‘Unofficial?’ he asks. ‘If I’m not mistaken, the caliphate of South Khandaros has already been recognized by Hamas and the Taliban.’

‘With endorsements like that who can argue?’

‘A far cry from the United Nations,’ he says with an easy laugh.

After a period of silence he says, ‘I think I’m too drunk to talk politics.’

‘And I,’ she says, ‘am perhaps not drunk enough.’

When the bistro closes, they walk through the lobby toward the elevator. He isn’t sure what will happen, how he should go about suggesting she come up to his room. But when the elevator doors close she turns to him and they kiss. He presses her against the wall and runs his hands up and down the sides of her body. They hardly disengage when the elevator arrives at his floor. She clings to him as they approach his room. Though still in public, technically, they seem to have dispensed with whatever decorum they might have observed downstairs.

Now they’re in bed. She lies beneath him and her lips move against his ear, muttering in French what could be either obscenities or endearments, possibly both. When drunk he has a tendency to feel abstracted, distant from himself, which adds to the strangeness of this foreign woman and this foreign place. He feels like he’s in a kind of free fall, the darkness beneath him opening wider and wider as he braces for impact. Afterward he rolls off her and waits for her to speak, but she says nothing, and in only a matter of minutes he hears the nasal rasps of her drunken sleep.

Just past four a. m. he wakes in a panic. He left his brother’s ashes in the bistro. At his table or Véronique’s, he can’t remember which. He races down to the empty lobby, and bangs his fist against the door of the bistro until a uniformed bellhop walks up behind him. The bellhop doesn’t have a key to the bistro. Only after Burkett hands him a twenty-dollar bill does the man call security. It takes half an hour for the guard to arrive and open the door. To his relief, the ashes wait undisturbed in the same chair where he left them.

The clock reads five a. m. when he returns to his room. He goes to the bathroom and undresses and drinks a glass of bourbon in the shower. Afterward he stands in the carpeted room with a towel around his waist. The rising sun casts a bar of light across his bed and the bare legs of the woman lying there.

While she sleeps, he unpacks his computer and checks his email. Two days’ worth of unread messages, at least fifty, wait in his inbox. There is a message from the Georgia Medical Board with his license number in the subject line. He holds his breath, feels his heart accelerate. It’s been less than a week since the hearing. Could the board have already decided his case?

He skims through the letter, pausing on the phrase ‘temporary suspension of your medical license’. After his third drunk-driving charge, the state of Georgia has deemed him unfit for surgical practice. If he undergoes treatment for substance abuse, the status of his license will be reconsidered in six months. The board has been kind enough to provide links to two treatment facilities.

His initial response, after shutting his laptop, is to go to the bathroom for a Xanax and a shot of siddique. He stares at his reflection as if waiting for it to give him some word of encouragement or condemnation. He climbs back into bed and drapes one arm across his eyes, but there is little hope of sleep. With the sun coming up he would need a higher dose to escape consciousness.

So he is now an unlicensed physician. He wonders if this is a decision he can appeal. Should he contact a lawyer? Baptist Hospital has hired him as general surgeon, to begin practice a week from today. His future partners gave him a generous signing bonus, which he now might be obligated to pay back. Perhaps even more generous was their offer to postpone his start date when his brother died.

Will they revoke the job offer? The status of his license should be a private matter. If no one asked, he could theoretically begin operating next week as scheduled. Perhaps he could find a local treatment program in the evenings. On the other hand, he would face criminal prosecution if it ever came to light that he was operating without a license.

Substance abuse. The words would have shocked his teetotal brother. Burkett, for his part, had always enjoyed the occasional binge, even when they were college wrestlers, but he wasn’t getting drunk on a regular basis till late in his first year of medical school at Emory. By fourth year, he and his classmates were out in the bars every night. During his internship and residency, it wasn’t uncommon for him to show up for rounds still drunk and reeking of smoke.

Owen, whose social life revolved around Bible studies and fellowship meetings, finished at the top of his class at Johns Hopkins and became a chief resident in surgery at Harvard. What a surprise it must have been to his attendings when he turned down a fellowship in pediatric surgery and entered the mission field.

Véronique rises and hurries to the bathroom, surprisingly modest of her nudity. With the shower running she reappears in a terry cloth robe to gather last night’s clothes. He gets up and makes two cups of drip coffee using bottled water from the non-alcoholic minibar. He pulls back the curtains for a view not of the ocean (his room faces in the wrong direction) but of moldering rooftops interspersed with minarets and columns of greasy smoke where people are burning their trash.