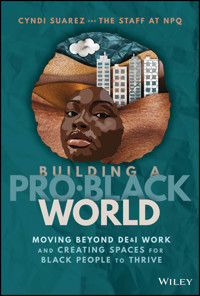

Building A Pro-Black World E-Book

22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Learn to create a nonprofit organization and society in which Black people can thrive In Building A Pro-Black World: A Guide To Creating True Equity in The Workplace and In Life, a team of dedicated nonprofit leaders delivers a timely roadmap to building pro-Black nonprofit organizations. Refreshingly moving the conversation beyond stale DEI cliches, editors Cyndi Suarez and the NPQ staff have included works from leading racial justice voices that show you how to create an environment--and society--in which Black people can thrive. You'll also learn how building such a world will benefit all of society, from the most marginalized to the least. The book explains how to shift from simply critiquing white supremacist culture and calling out anti-Blackness to actively designing for pro-Blackness. It offers you: * Incisive and engaging work from leading voices in racial justice, Cyndi Suarez, Dax-Devlon Ross, Liz Derias, Kad Smith, and Isabelle Moses * Explorations of topics ranging from restorative leadership strategies for staff wellbeing to Black politics and policymaking * Discussions of new language for pro-Black social change, racial equity in healthcare and health communications, and antiracist succession planning A can't-miss resource for civil society and nonprofit leaders, including directors, executives, grant makers, philanthropic donors, and social movement leaders, Building Pro-Black World will also benefit communicators, organizers, and consultants who work with nonprofit organizations.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 475

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

I: Enacting Pro-Black Leadership: A Better World Is Possible

Going Pro‐Black

Defining

Pro‐Black

What Does

Pro‐Black

Mean?

What Are the Characteristics of a Pro‐Black Organization?

What Would a Pro‐Black Sector Sound, Look, Taste, and Feel Like?

Note

When Blackness Is Centered, Everybody Wins

Notes

Leading Restoratively

Our Promise to the Community

Pro‐Black Organizational Leadership

Reimagine Staff Wellness

Prioritize Psychological Safety

Restore Worker Dignity

Build Leadership Pipelines

Conclusion

Notes

II: Building Pro-Black Institutions: Narrative and Forms

What It Looks Like to Build a Pro‐Black Organization

The Failures of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI)

Interrogating Governance to Construct a Pro‐Black Organization

Supporting Organizations to Build Pro‐Black Structures

Notes

To Build a Public Safety That Protects Black Women and Girls, Money Isn't the Only Resource We Need

Narratives as Symbolic Resources

Oppressive Narratives That Shape Perceptions of Black Women in the United States

Black People and the Police

A Framework for Making the Visible Invisible

Notes

Combatting Disinformation and Misinformation

Framing the Problem

Online Disinformation's Racist Impact

Old Narratives, New Tactics

The Rise of Anti‐Trans Disinformation

The Mainstreaming of White Supremacist Ideology

Reframing False Narratives

How to Combat Disinformation

Forms

Notes

Hierarchy and Justice

Hierarchy as a Form

Functional Hierarchies

Forming Justice

Notes

A Journey from White Space to Pro‐Black Space

The Dam Breaks

New Leadership Sets an Audacious Vision—and Offers a Framework for Action

Organizing Human Resources as If People Matter

The Need for New Thinking

Notes

III: Building Pro-Black Institutions: Philanthropy and Evaluation

The Emergence of Black Funds

Notes

Reimagining Philanthropy to Build a Culture of Repair

A New Philanthropic Model

Rooting the New Model in Repair

A Journey—Not a Destination

Toward a Liberated Future

Notes

How Philanthropy Can Truly Support Land Justice for Black Communities

Self‐Determination and Land Justice

Our Freedom Dream

Notes

What Does Black Feminist Evaluation Look Like?

Notes

Nothing Is Broken

Notes

IV: Implementing Reparations: Health and Well-Being

Revolutionary Black Grace

Scars from the Language of Whiteness

Between Us … Black Women and Men

Honoring Our Journey, Finding Our Connection

Black Privilege Is Not the Answer

The Emotional, Not the Political

Notes

What Is Healing Justice?

Our Collective Wisdom and Memory Enable Well‐Being

Wellness Is Liberation

Our Interdependence Is Essential

Our Wellness Requires Honoring All Bodies

A New Vision for Addressing Structural Racism

Notes

The US “Healthcare System” Is a Misnomer—We Don't Have a System

Equitable Care

Driven by Profit

The Racial Divide

Black Distrust

Health Equity

Data‐Driven Solutions

Systemic Alignment

Notes

Pro‐Black Actions That Health Justice Organizations Can Model

Acknowledgment: A Vital Antiracism Tool

Acknowledging Racial Health Disparities to Address Them

Understanding Health Equity

Next Steps, Sustained Actions

Notes

Repairing the Whole

Can Reparations Heal?

Reparations and Trauma

Acknowledgment of Harm

Increasing Black Wealth to Improve Black Health

Decolonization of the Medical Industry

Turning Research into Action

Notes

Addressing Inequities in Health Technology

Systemic Risks Associated with Healthcare Technology

Activism to Address the Harms of Health Technology

Notes

V: Implementing Reparations: Work and Ownership

Resurrecting the Promise of 40 Acres*

Eligibility: Black American Descendants of Persons Enslaved in the United States

Calculating What Is Owed

Prioritizing the Mean of the Racial Wealth Gap

The Cost of Slavery

The Promise of 40 Acres

Culpability: A Matter of National Responsibility

Learning from Other Cases: Precedents for Reparations

Precedents for HR 40: Lessons Learned

Conclusion

Notes

Solutions Centering Black Women in Housing

A History of Racist Policies

From Racist Exclusion to “Predatory Inclusion”

Toward Repair: Addressing Black Women's Exclusion from Housing

A New Vision: Centering Black Women in Housing

Notes

Linking Racial and Economic Justice

The Long March of Institutions

Challenging Harmful Narratives Through Data Linked to Activism

The Importance of Historical Analysis

The Struggle for Economic Democracy

Notes

What If We Owned It?

Organizing for Sovereignty

The Emergence of Black Food Co‐ops

Healing for Sovereignty

Completing the Action That Was Thwarted: Moving Through Trauma

Building for Sovereignty

Developing a Food Co‐Op: Seven Principles

Seven Internationally Recognized Co‐op Principles of the ICA (International Co‐operative Alliance)

Notes

How Do We Build Black Wealth?

The Enduring Appeal of Black Capitalism

Black Capitalism's Shortfalls

Capitalism and Inequality

Can Racial Capitalism Be Reformed?

What Do Racial and Economic Justice Require?

Notes

VI: Organizing for the Future: Community and Politics

Making Black Communities Powerful in Politics—and in Our Lives

Notes

Justice Beyond the Polls

Black Youth Fighting Voter Suppression

Investing in Black Youth: Beyond Electoral Engagement

Black Youth Organizing for a Better Future—For Everyone

Notes

The Liberatory World We Want to Create

Love, a Forgotten Tongue

Medicine to Harvest

Cancel Culture

Building a Bridge Together—One Ancestor, One Bone, One Ligament at a Time

Loving Accountability—an Antidote

Notes

Dimensions of Thriving

Rejecting the Deficit Approach, the Medical Model, the Status Quo

Pursuing a Bridge to Thriving

Surviving Encounters with Oppression

What Is Thriving?

Notes

Pro‐Blackness Is Aspirational

About the Authors

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

About the Authors

Index

Wiley End User License Agreement

Pages

iii

iv

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

79

80

81

82

83

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

101

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

179

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

235

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

BUILDING A PRO.BLACK WORLD

MOVING BEYOND DE&I WORK AND CREATING SPACES FOR BLACK PEOPLE TO THRIVE

CYNDI SUAREZ AND THE STAFF AT NPQ

Copyright © 2023 by Nonprofit Quarterly. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.

Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per‐copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750‐8400, fax (978) 750‐4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748‐6011, fax (201) 748‐6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762‐2974, outside the United States at (317) 572‐3993 or fax (317) 572‐4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781394196906 (cloth)ISBN 9781394196890 (ePub)ISBN 9781394196876 (ePDF)

Cover design: Paul McCarthyCover art: © Devyn Taylor

IEnacting Pro-Black Leadership: A Better World Is Possible

Going Pro‐Black

Cyndi Suarez

At the end of 2021, NPQ convened an advisory committee on racial justice and asked the question, What is the edge of current racial justice work? The group converged on “building pro‐Black organizations.”

I had several experiences at the same time that reflected a deep schism in racial justice work, depending on where one is situated. The crux of this schism is the line that divides nonprofit organizations and philanthropic ones.

One experience: while participating on a panel on media covering philanthropy, I was asked to speak on the recent controversy in a large philanthropy network. I was unaware of the controversy, but when a fellow panelist eagerly weighed in, I learned that it was that conservative philanthropists feel the philanthropic sector is too radical, which made them feel there was no room for them. On hearing this, I shared that I did have a perspective on this. It perfectly illustrates the lack of alignment of which I'd been speaking earlier between the field and the funders: that no one I knew was accusing philanthropy of being radical—in fact, quite the opposite; it is being held accountable for not living up to its touted values; and, finally, that we needed to consider what, in fact, is the purpose of philanthropy. This caused quite a stir and excitement in the audience, some of whom emailed me later to tell me what “a breath of fresh air” it had been to hear me speak what they know to be the truth. Though it also made me wonder: why are so many in philanthropy sitting on their truth? What are we waiting for?

Another experience: a large philanthropic network sought to partner with NPQ to work with its leading‐edge funders, who are all interested in advancing racial justice. These funders hope to inspire the field with their leadership on the issue. Their main interest in partnering was in connecting with leaders of color in the field. It just so happens that NPQ has been investing in highlighting the voices of leaders of color, as they are woefully underrepresented in the sector. But the network had one caveat: that we change our language and work to not focus on leaders of color. But we are. What's wrong with saying that?

A third and final example: a big funder approached me about working with its staff on race and power. One of its key values is being bold. Yet, while the focus of the funder is to advance grassroots movements, the staff members are reluctant to “give up power” and there is a “scarcity mindset.” In fact, it is not yet in conversation with grassroots movements. As one of NPQ's staff members recently said in a meeting, “Are we ever going to move past symbolic solidarity?”

We're moving beyond DEI (bodies at the table), racial equity (measuring POC against white people), and perhaps even racial justice (the righting of racial wrongs) to an actual focus on what Black people need to thrive (building pro‐Black).

These parallel realities exist right now. But there is a gap between the leaders of color and radical white conspirators at the edge—and the funders who claim to be.

It's high time we focus squarely on the goal and stop talking around it. Like most consequential change, it's going to require new language. Not everyone will be comfortable with that, but if you want to be at the edge or bold, step up to the future waiting to emerge.

Defining Pro‐Black

Cyndi Suarez

There is a shift afoot in the field, from critiquing white supremacist culture and calling out anti‐Blackness to designing for pro‐Blackness. So, we followed up with some of the writers who lent their expertise to this edition and also interviewed Shanelle Matthews, the communications director for the Movement for Black Lives in order to go more deeply into defining what we mean by pro‐Blackness. We asked them the following questions:

What does pro‐Black mean?

What are the characteristics of a pro‐Black organization?

What would a pro‐Black sector sound, look, taste, and feel like?

The conversations that ensued can be found in full in Spring 2022 issue of NPQ. What follows are some of the main takeaways from those interviews.

What Does Pro‐Black Mean?

The key characteristic of pro‐Blackness is that it deals with power. In fact, pro‐Black means not only directly dealing with power but also building power for Black people. As such, it is perceived as a bold or daring statement that often triggers discomfort in white people.

Dax‐Devlon Ross, writer and equity and impact strategist, shares his reaction to being invited to be part of a conversation on being pro‐Black:

It made me think of Black Power and discomfort. It also made me feel a certain level of challenge. I thought, Oh, they want to go there with this! And it literally sent a sensory experience through my body. And I thought, Okay, let's go; let's actually explore this and try to forget about all the people who might be offended, or who might say, “Oh, but what do you mean, and who are you leaving out?”… Let's just name and center this right here as pro‐Black.

Liz Derias, codirector at CompassPoint, a nonprofit leadership development practice that has been focusing on pro‐Black approaches for the past few years, says,

To be pro‐Black is to build pro‐Black power. And when we talk about building power at CompassPoint, we define it as building our capacity to influence or shape the outcome of our circumstances.

Shanelle Matthews, communications director for the Movement for Black Lives, says,

For me, the root of this conversation is power. So, that's being able to exist as a Black person in this country without the gaze of whiteness or having to pretend to be somebody that one is not, in terms of one's self, one's identity, and one's self‐determination in one's everyday life.

Building pro‐Black power requires an understanding of what power means for Black people. Derias says,

Building Black power, building pro‐Black organizations, and building a pro‐Black movement requires us to take a look back at the ways that power has existed for us in our communities before systems of oppression in an effort to bring it into the current context—not only to challenge the systems of oppression but also to carry forward what has been intrinsic to our communities.

Matthews agrees:

At the root of what I think pro‐Blackness is about is advancing policies, practices, and cultural norms that allow Black communities to be self‐determined and for us to govern ourselves. To have enough economic, social, and political power to decide how, when, and where to have families. To determine where to live. To have the choices and the options to make decisions, just like everybody else—about schools, education, jobs, and quality of life.

There's also an element [about] governance. What does it mean to be able to determine how our cities exist? We are often cornered into particular places inside cities that don't give us very many options in terms of grocery stores … and other essential needs.

There is a point of tension about whether pro‐Blackness takes anything away from other racialized groups. For Ross, his expected negative reaction from white people is one that demonstrates a misperception of what pro‐Black actually means. He says,

It's not just a place where Black folks can thrive and be. It's a place where all folks can thrive and be. Because in my understanding, and how I have referenced and thought about history, whenever Blackness is centered, everybody wins.

However, Isabelle Moses, chief of staff at Faith in Action, has a different take:

I guess it depends on what people value, what they perceive as giving up versus not giving up. So, if people value having the top job, and if that's a zero‐sum thing—where the only way you can express leadership or power is by being the top of whatever the food chain is, or the apex predator, so to speak—then yeah, you might feel like you're giving up something. But if you can reframe what it means to be powerful, then I think we have a chance.

***

So, it just depends on how people think about what the trade‐offs are. And I think if we can collectively reframe the trade‐offs, then we get closer to creating more conditions for more people to thrive—which, in my opinion, is way more rewarding than having the most money that I could possibly have for myself.

For Matthews, there isn't a misperception about what pro‐Black means in terms of power. In fact, that is exactly where things fall apart. She observes that being pro–Black Lives Matter does not mean one is pro‐Black. The “racial reckoning” of the last few years has led many to publicly voice their commitment to the Black Lives Matter social movement. But class interests often clash with these commitments. She says,

For all the people who bought the books, who had one‐off conversations, who marched in the streets, who maybe replaced one white board member with a Black board member—well, I don't want to diminish people's commitments … but those actions are insufficient. The question we have to ask ourselves is, What are we willing to give up in order to be pro‐Black?

Moses concludes:

Pro‐Blackness isn't a zero‐sum game. It shouldn't be seen as anti anything else. I think right now there's this kind of binary orientation. But I think we need to understand pro‐Blackness as a way of saying pro‐everybody—and by that I don't mean the equivalent of “all lives matter”! What I do mean is that if you're pro‐Black, you are actually pro‐everybody, because you can't be pro‐everybody if you're not pro‐Black.

Pro‐Black also means Black people being able to be authentic. Kad Smith, an organizational development consultant, asks, “What would it look like to truly honor the experiences of Black folks, with no asterisk? As in, no conditions attached to the question of what kind of Blackness is palatable and what kind isn't.” Quoting from a CompassPoint‐led cohort member, Smith continues: “Pro‐Blackness just looks like being comfortable in my skin.”

Matthews echoes this:

People often support a particular type of Blackness. So, folks are comfortable with people going out and protesting, but if things get what they feel is unwieldy, or people start to uprise in a way that is uncomfortable to them—so, folks bashing in police cars, because police have killed their family and they don't particularly care about that piece of property over the dead bodies of Black people, or the movement's demand shifting from accountability to defunding the police—then we often see people's allegiances to the movement fade.

For Moses, the path to pro‐Black is a very personal one of becoming grounded in Black culture, as both identity and community.

I live in Detroit, Michigan. I've been here for about four and a half years. And one of the reasons I moved here was to be grounded more in Black culture. I grew up in a supersocialized, white context in San Francisco, going to private schools. Then I lived in Washington, DC, for a long time. And I wanted to have a more rooted experience in Black communities. And Detroit, I felt, was a place where I could have that experience of being somewhere that really values and centers Black culture as just everyday life. I felt like I hadn't had that experience before… . So, that sense of rootedness in Black community is something that I have been longing for.

She continues,

I've learned that it takes more than just having Black skin. What I've learned, at least for myself, is that because of the era that I grew up in—the colorblind era, the 80s and early 90s, when folks were embracing this kind of assimilation mantra—I needed to reclaim my identity as a Black person. Because the frame that you're asked to assimilate into is obviously a white normative frame.

Basically, to be pro‐Black is to not have to adhere to the white‐dominant status quo.

What Are the Characteristics of a Pro‐Black Organization?

Themes are emerging for those building pro‐Black organizations. At its most basic, it means being able to talk about issues affecting Black people. Smith shares,

We're met with a certain level of resistance when we speak about Black‐specific issues. So, that is anti‐Blackness rearing its head in a very petulant and kind of gross way when Black folks talk about things that are particular to Black people and are met with resistance. A lot of what was coming up in articulating the pro‐Black organization is the eradication of that dynamic. So, I can speak to what it means to be a Black person even if I'm the only one. Or even if I'm one of four. I'm not going to be met with, “Wait, wait, wait. We're not anti‐Black. We're not racist.” We're going to say, “Oh, let's go further there. Let's understand what's coming up for you.” I feel like that would be in lockstep with other movements toward progress.

This is very tied to another characteristic of a pro‐Black organization: Black people being able to step into power without punishment. Smith explains, “A couple of folks from the [CompassPoint] cohort mentioned safety. Safety from discrimination, from undeserved consequences, from systems of oppression.”

Being disadvantaged by existing organizational policies is also punitive. Derias shares,

When I came in [to CompassPoint], I observed that the majority of people who worked at the organization were women, and all the Black women at the organization were mothers… . We took a look at what it is that Black mothers value. They value the health of their children. They value time with their children. They value psychological safety for themselves and not to have to be here and worry about their children… . And the organization didn't offer 100% dependent coverage. So we had mothers, and sometimes single Black mothers, working at CompassPoint and then working at other jobs just to provide healthcare for their children.

So, in an attempt to build a pro‐Black organization, we decided to flip that policy on its head. We wanted to figure out how to prioritize putting money into supporting our staff [members], which at the core would mean supporting Black mothers. This year we passed a policy of 100% dependent coverage for all our parents. Centering Black women wound up expanding the center, because now all of our staff [members] … can get care for their children… . When we center Black people, we challenge the punitive nature of organizations.

Isabelle Moses agrees.

We operate at Faith in Action under the belief that if you take care of Black people, specifically Black women, everyone in the organization will be taken care of—because the needs of Black women in particular are often so overlooked. And Black women are expected to be the providers, the caretakers, the folks who do things without actually ever being asked, and a lot of that labor goes unseen, unrecognized, unappreciated. And if you start to pay attention to all of the things that Black women do to make an organization successful, and then you provide resources and support for that work to be compensated, to be appreciated, to be recognized, then you realize how much more people actually need in order to thrive in organizations.

And when you meet those needs—when you create space for people to take care of their families during the workday; when you create space for people to take meaningful vacations so that they get actual rest; when you create the conditions for really strong benefits and policies, so people's healthcare needs are provided for (and they're not worried about whether they can make their doctor's appointments on time, because they know that they have the time off to do that); when you create an environment where people aren't going to be pressured to deliver things at the last minute, because you build in time and space for thoughtful planning so it doesn't end up on somebody's plate (often a Black woman's)—then you can create an organization where Black women can thrive. And if Black women are thriving, everybody is thriving. That's our fundamental belief.

Building pro‐Black organizations means going beyond challenging structures to designing new structures with the values and needs of Black people at the center. Derias says,

Building pro‐Blackness and building power require much more than just defending ourselves against anti‐Blackness, and much more than just asking white folks in the organization to take a training. It's really about moving the needle with respect to looking at Black people as the folks who develop our governance, as the folks who, by virtue of our values, lead the development of the systems, policies, practices, and procedures at the organization.

Some organizations institute sabbaticals, which give staff members much‐needed time to reflect and consider their next move in the work. At Faith in Action, staff members who have been there for 10 years or longer are eligible. Moses explains,

Depending on what they need, [a sabbatical can be] anywhere from three to five months. And they can put together a plan for the time. Our colleague Denise Collazo used her time to write a book, Thriving in the Fight. Denise has been organizing for twenty‐five years and is now our chief of external affairs. And she talks a lot about how that sabbatical was one of the ways in which she got the space that she needed to do the reflection for that book. So, she was able to use that time off to get clear about how it was that she was able to stay in the work.

Denise was an innovator of our Family–Work Integration program, where we strive to reduce meetings on Fridays and limit email. It's not a day off, but it is a day that you can use to meet whatever needs you have—to catch up on any work from the week that didn't get done, or sleep in a little and go to a gym class, or take your mom to a doctor's appointment, or take care of that errand that you've been meaning to do—so that you don't end up feeling like there's no time for those activities that are really important for one's well‐being. If you center well‐being, then you create more opportunity to do better work… . And people are happier. We have a much happier culture.

Building pro‐Black organizations also includes resourcing Black programmatic work. Derias shares,

We had a plurality of Black staff [members] for the first time in CompassPoint's 47 years… . This is important to note, because what we found is that it's really hard to build pro‐Blackness when you are the sole Black person at the organization. I mean, it's like moving a mountain. And so that plurality provided an opportunity for the Black staff [members]to get together and really interrogate pro‐Blackness internally. And as we did that, we really built unity—we built across our values. And that's when we decided that it was really important for us to resource our Black programmatic work.

Moses agrees, and she shares how being a recipient of a MacKenzie Scott gift makes it possible:

We want to make sure that our teams are resourced. With the gift that we got last year from MacKenzie Scott, we now have the resources to make sure that people can work reasonable hours. If there's a gap in the organization, we can create a job description and recruit for it. We don't have to operate out of scarcity; we can operate out of abundance. And that's so exciting.

This type of pro‐Black change in an organization usually requires having Black leadership.

Moses says,

I have a hard time seeing how folks who aren't Black can understand what Black folks need in an organization. Truly. And how they would be able to resource it at the level that's required. That doesn't necessarily mean the top people all need to be Black; it just means you have to have meaningful representation of Black folks in leadership, in order for that ethos to get rooted all the way through the organization. I've worked in organizations where there were Black staff [members], but we didn't have enough power for things to change.

Supporting Black leaders is also critical. I, and others, have written extensively about how they do not have the support they need and often face the sector's most pressing challenges.1 Derias says,

Now that we have Black people who are taking up positional power, it's really important to support them. I think what would strengthen the sector is giving time and space for Black people in positional power to learn skills, to network, to vent, to pool resources.

The challenges Black leaders face come from systemic, sectorwide forms and from within organizations and Black staff members, many of whom want to be experimenting with alternatives to hierarchy.

CompassPoint provides an example. The organization recently underwent a leadership transition that included an interim period during which it tried the holacracy method of decentralized management. It then decided to move forward with a codirectorship model. As Derias describes it,

At the core for [CompassPoint] as we were building a pro‐Black organization was experimenting with a new governance model. Holacracy was useful, but it didn't meet our needs—so, we're developing a new kind of governance model. There's nothing really new under the sun—but what it does is push us to center our values.

Smith, who was at CompassPoint during this time of change, adds nuance.

I'm just gonna speak plainly: There was a sense of a commitment to holacracy and shared leadership, and the Black folks on staff [members] were doing some of the implementation and evaluation of that work, and it increased their responsibility and created visibility [for] their leadership—my own included. And when the organization committed to moving away from that, that was one of the few instances that I would say CompassPoint unintentionally perpetuated anti‐Blackness.

Supporting Black leadership can appear to be in conflict with what Smith refers to as Black self‐determination. He asks, “What does it look like to have autonomy and agency in an organization that intrinsically depends on collaboration?”

Ross sees this conflict about leadership and forms in his work, too.

What can come next can only come next if we allow for something that has not been allowed, has not been given space to really, really breathe. When I think about organizations, they're still not giving space to breathe… .

How I see that showing up primarily right now is in many ways centered on the question of how we organize ourselves as an entity. And so you're seeing a lot of folks contesting the model of hierarchy that organizes and cements power in this very concentrated place at the top of the organizational chart. People really want to contest that and find out what are the distributive ways in which we can organize ourselves… .

Pro‐Black creates the space for that which needs to evolve to evolve. Pro‐Black, to me, is connected to the notion of adaptation. It's connected to, and very much rooted in, the notion of interdependence. It is connected to and rooted in the notion of ideas [about] vulnerability, and different forms of knowledge and knowing. All of those are invitations to do the exploratory work that is necessary to find out what is next.

There is an opportunity for nonprofit organizations to evolve by learning from Black people's history and victories, particularly in how to build liberatory identities. Ross says,

A lot of organizations are in the midst of an identity crisis right now. After two years of racial reckoning, they are really deeply asking, “Who are we?” It's being asked at the generational level. We have younger folks asking the organizations who they are, and it's causing older folks to ask the question of themselves… .

And who in our country has had their identity contested again and again and again, and has had to figure out who they are again and again and again? Black folks. Identity has always been a question: “Are you really human?” “Are you American?” That question of identity has always been at the core of how we have had to orient ourselves and survive… .

What can nonprofits learn from folks who've had to go through that and answer that question repeatedly over their history in this country?

One way that Black people have defined liberatory identities is by moving beyond binaries to hold multiplicity. This can be a challenge for everyone, including Black people. Ross says,

I spend a lot of time looking at Patricia Hill Collins's work [about] Black feminist epistemologies… . I find myself referring repeatedly to an article she wrote 36 years ago… .

She was pushing against binaries in her work. She says—and I paraphrase—”Don't use what I am proposing here as a world, as the replacement for what currently exists, because that is a problem as well.” That's still the binary… .

It's much more complex and nuanced to recognize and be able to hold the multiplicity [about it]… .

And, to be quite honest, one of the things that I find in organizational spaces right now—that is, I think, a developmental process—is that the calling out of white supremacist culture is being used as its own kind of bludgeon. It's becoming now its own orthodoxy, and so everything has to line up in that way.

For Matthews, becoming a pro‐Black organization depends on the people in it doing difficult, personal work. For this, the organization needs to be providing political education. She says,

There is no way to enter movement and genuinely advocate for radical ideas without interrogating your allegiances to oppressive systems. So, if we're not offering political education to our staff and board [members] to understand the complexities and history of anti‐Blackness, not only in the United States but also globally—so that they can have enough context to be able to authentically make some of the political decisions and commitments that they want—then we're missing the mark.

The debate [about] critical race theory illustrates just how hard it is for us to educate people in America about the history of atrocities that this country has perpetrated against Black people. So, we have to make that commitment in our organizations.

There is tension or conflict not only within organizations, and between organizations and movements, but within movements as well. Matthews shares that movement spaces aren't always pro‐Black either. She admits, “Our movements can be inhospitable to people who are growing.”

What Would a Pro‐Black Sector Sound, Look, Taste, and Feel Like?

Imagining a pro‐Black sector did not come easily to the writers with whom I spoke. However, the contours are beginning to take shape. One thing is for sure: people want more humanity. At the center of it is Black comfort and joy.

The sound would be that of a space ringing with the laughter of Black solidarity. Ross says,

There's laughter, there's commiseration. [Leaders of color are] finding community with each other, and they're not seeing one another as competitors or as people they need to feel threatened by. They're defining their tribe.

It would look like trust. Ross says,

It looks like people being trusted to have a sense of what's needed but also of what's comfortable and what's connected to impact. Because if it's not connected to impact—if it's not connected to what our mission is—why are you putting it on me? … My presence and how I show up in the world shouldn't be making you comfortable or uncomfortable.

… And the trust would extend to foundation partners really resourcing this work. Derias says,

It's really important that we not be beholden to projects or initiatives that have concrete, predetermined outcomes driven by our foundation folks… . Allow us to do the work of building the capacity of staff [members] to play with this vision of pro‐Blackness, to experiment with it internally, to experiment with it externally. That's really important for our sector.

It would taste like the deliciousness of complexity. Ross imagines,

It would taste like some kind of fruit that sort of explodes in your mouth, and each bite provides you with something distinct that you never imagined before. You've had that flavorful dish that starts off tasting one way with that first bite, and then the second bite adds another flavor, and the third bite another, and it produces a sensory joyfulness that you want to keep processing. You're not trying to just get to the next bite—you're really enjoying the bite that's in your mouth, what's going down.

It would feel relaxed. Ross says,

There's a lot of haste in the work. A lot of unnecessary urgency pervades. And I think pro‐Black space, pro‐Black identity, pro‐Black work, and folks who are centered in pro‐Blackness are very clear—we need to slow down sometimes.

Different cultures can have different relationships with time. For people of color, it can be more qualitative than quantitative.

Moses shares how Faith in Action has instituted rituals that are familiar to staff members of color, such as spending considerable time in meetings checking in. She says,

We recently had an hour‐long meeting with twenty‐five people, and we spent 25 minutes of the meeting with everyone calling in the ancestor that they wanted to bring into the space. And then we spent 35 minutes getting all the business done that we needed to do. And when you spend 25 minutes hearing each other's personal stories, that's a way of centering Blackness, centering Black culture, and centering the fact that we are more than the people in this room. We are all the people who came before us. We are all of the wishes and aspirations that our ancestors had for us, and often have exceeded those… . And when you really create space for that conversation, it builds community, it builds deeper trust, it builds deeper relationship, and it allows for better conditions for the work.

For Matthews, pro‐Black is ultimately an aspiration:

If you look at the trajectory of the Black liberation movement throughout the twentieth and the twenty‐first centuries, there are some clear indications that the movement is becoming more pro‐Black… . One of the major distinctions between the civil rights movement and the Black Power movement of the 60s and 70s and this current iteration of the Black liberation movement is that our leadership is decentralized and queer‐ and women‐ and nonbinary‐led. Some people would say, “What does that have to do with being pro‐Black?” Well, if Black people who are nonbinary, transgender, and/or women do not have power in your movements, then you cannot proclaim to be pro‐Black, because you are only pro‐Black for some.

Even now, there are important critiques about this iteration of the Black liberation movement—and our job is to listen, repair harm, discuss, and course‐correct… .

There is no pinnacle of pro‐Blackness at which one will arrive… . We are changing, and our material conditions are changing, all the time. And we have to evolve with those changes. Every single day, there are new ideas we have to contend with—and that means constantly evolving our strategies, our thinking, and our behaviors to be commensurate with those new ideas.

Note

1

See, for example, Cyndi Suarez, “Leaders of Color at the Forefront of the Nonprofit Sector's Challenges,”

Nonprofit Quarterly

, February 3, 2022,

nonprofitquarterly.org/leaders-of-color-at-the-forefront-of-the-nonprofit-sectors-challenges/

.

When Blackness Is Centered, Everybody Wins: A Conversation with Cyndi Suarez and Dax‐Devlon Ross

In this conversation about defining pro‐Blackness, Cyndi Suarez, Nonprofit Quarterly's president and editor in chief, talks with Dax‐Devlon Ross, author, educator, and equity consultant, whose latest book, Letters to My White Male Friends.1 is garnering well‐deserved attention.

The conversations that ensued can be found in full in Spring 2022 of NPQ.

***

Cyndi Suarez:

Dax‐Devlon Ross:

Let's just name and center this right here as pro‐Black. It's not just a place where Black folks can thrive and be. It's a place where all folks can thrive and be. Because in my understanding, and how I have referenced and thought about history, whenever Blackness is centered, everybody wins.

And I feel like that's what's always missing from these conversations in organizations. Leadership is always saying, “If we focus too much on race, who are we forgetting, who are we leaving out?” But if we look at the history of this country, whenever we are focused on race in this way, the benefit has accrued to so many other groups of people. So, let's not get caught up in this conversation centered on fear of being too up front [about] race because that might be perceived as not intersectional or not taking into consideration other experiences. Because the history of Black folks has never been one where we have not looked at and thought about other folks on the journey.

So, when you put out that call for folks to think about what pro‐Black would look like in the organizational (and intersectoral) world, my feeling was, Let's think about this not just as a place where Black folks can be and thrive but also a means of thinking about where and how the values that have persisted within Black freedom struggles become the values that get mapped onto the sector. For example, what do we know to be true about emancipation? What do we know to be true about the fight to end Jim Crow? What do we know to be true about Black Lives Matter? These are movements that developed worldviews, epistemologies, forms of knowledge‐making and creation and ways of knowing that allowed for these movements to be successful in advancing in the face of all sorts of terroristic threat. And yet, we've never really thought about how we could adopt some of what they did and do—the things that they learned and had to build around as a worldview, as a philosophy, as ideology—and apply it to our work in our sector. I hear sometimes, “Let's get some Black folks in here. Let's bring in Black folks or folks of color into the organization.” But I never hear, “How do we develop and evolve our worldview [from] the intelligence they bring?” Because that worldview exists already. We've seen plenty of evidence of its power and its ability to shift power, but it never gets adopted and brought in as legitimate and serious forms of organizing and developing and building in the mainstream context.

What I landed on was that I wanted to be able to help folks to think about a way forward, because a lot of organizations are in the midst of an identity crisis right now. After two years of racial reckoning, they are really deeply asking, “Who are we?” It's being asked at the generational level. We have younger folks, folks of color, folks of different identities asking the organizations who they are, and it's causing older folks to ask the question of themselves. People are struggling with their identity.

And who in our country has had their identity contested again and again and again, and has had to figure out who they are again and again and again? Black folks. Identity has always been a question: “Are you really human?” “Are you American?” That question of identity has always been at the core of how we have had to orient ourselves and survive. And if I see a sector right now really having a challenge [about] its identity, it's the nonprofit sector. What can it learn?

What can nonprofits learn from folks who've had to go through that and answer that question repeatedly over their history in this country? There's something to be learned there.

CS:

DDR:

CS:

DDR:

To build a little bit off of what you're saying, I want to frame whatever I write very clearly in the understanding that I am building off of and building for additional work, thinking, whatever else can evolve. I spend a lot of time looking at Patricia Hill Collins's work [about] Black feminist epistemologies, for example. I find myself referring repeatedly back to an article she wrote 36 years ago as I think about this work.6 And it is often the case, of course, that Black feminism in particular is a place where we can go to get a sense of a lot of things—because it has had to orient itself in such opposition to what it is always encountering in the academy, in the world, in the workplace. And one of the things that she talks about and plays with in her work—and I think this is really important—is the notion of standpoint theory. The idea that, rather than us starting to develop a sense that our role, our objective, is, as Black feminists (that's her context) to decenter the white male hegemonic order and replace it with a Black feminist frame, let's use standpoint theory as a way to understand that this is one way of interacting and understanding the world, one form of identity—and that there are many, many other ones as well.

She was pushing against binaries in her work. She says—and I paraphrase—“Don't use what I am proposing here as a world, as the replacement for what currently exists, because that is a problem as well.” That's still the binary—it's still this notion that we have to replace one with the other. It's much more complex and nuanced to recognize and be able to hold the multiplicity [about] it. And what I want to name—and am always resisting, even in my own work—is that I don't want it to be perceived as arguing for doing away with what has existed and bringing in a new thing that is the complete opposite of it. Because, for me, that doesn't necessarily move us forward. It gets us another frame that's valuable, but it also has its own potential shortcomings, its own foibles. And it keeps us in that same binary, either/or construct that we're trying to push ourselves out of and push through.

And to be quite honest, one of the things that I find in organizational spaces right now—that is, I think, a developmental process—is that the calling out of white supremacist culture is being used as its own kind of bludgeon. It's becoming now its own orthodoxy, and so everything has to line up in that way. So, if something in any way checks that box, it's bad, and we need to get it out of here. But that's not necessarily the world I'm in. My lived experience, my history, is complex. For instance, I was educated in a variety of institutions, some of which were white, and for me there is value in a lot of the knowledge that I developed at those institutions. What I am trying to challenge is the notion that this is the default and the only way, and that it is the one that has to be honored as the form, and in opposition to any other form of knowing and knowledge and ways of being in the world. And I'm presenting these Black freedom struggles as a worldview that has had to evolve in constant reaction to—in relationship with—that dominant frame.

So, it's not the way out, but it is a way forward. What can come next can only come next if we allow for something that has not been allowed, has not been given space to really, really breathe. When I think about organizations, they're still not giving space to breathe. I keep finding as I write and read, such as in pieces I've seen at NPQ, that folks have recognized