Building Utopia: The Barbican Centre E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

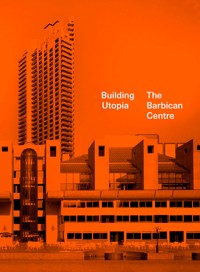

A beautifully designed celebration of the 40th birthday of the Barbican Arts Centre, in the heart of the City of London. It is the largest multi-arts centre in Europe, encompassing an art gallery, theatres, concert halls, cinemas and a much-loved conservatory, and regular collaborators include the London Symphony Orchestra and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Compiled by Nicholas Kenyon, the Barbican Centre's Managing Director 2007–2021, this is an in-depth exploration of the centre, drawing on the vast array of material available in its archives, much of which has never been seen before. It includes plans and photographs from the centre's design and construction, original signage and branding, and brochures and programmes. All this is accompanied by a wealth of photographs of the huge range of performances and exhibitions that have taken place over the years, from early RSC performances to the popular Rain Room installation of 2012 to today's impressive programme of events put together in conjunction with schools and the local community. The book's authoritative and evocative text includes: - Foreword by Fiona Shaw - Introduction by Sir Nicholas Kenyon - Cultural historian Robert Hewison on how the centre came into being - Architectural historian Elain Harwood on its architecture - Music critic Fiona Maddocks on music - Writer and theatre critic Lyn Gardner on theatre - Editor and creative director Tony Chambers on visual art - Author and film critic Sukhdev Sandhu on film With listings of Barbican events from 1982 to the present day, and snippets of oral history from some of the many people associated with the centre over the years, this sumptuous book is an invaluable companion to one of the world's most important cultural spaces.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 377

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Illustration by Russell Bell, 2014. This shows the Barbican development superimposed in colour on the Ordnance Survey map of the area before the Blitz of 1940/41. In the centre of the picture is the surviving church of St Giles Cripplegate, which provides the alignment for the whole estate. On the left is the semicircular shape of Jewin Crescent, echoed in the Barbican’s new Frobisher Crescent.

Contents

Preface

Nicholas Kenyon

Foreword

Fiona Shaw

‘Serious and fine entertainment’

Robert Hewison

‘A fuller way of life’

Nicholas Kenyon

‘A haven of cultural perfection’

Elain Harwood

Concrete

Roma Agrawal

Running the Barbican 1

Philip Dodd

Music

Fiona Maddocks

Theatre

Lyn Gardner

Running the Barbican 2

Philip Dodd

Brand Barbican

Theo Inglis

Art

Tony Chambers

Cinema

Sukhdev Sandhu

Running the Barbican 3

Philip Dodd

Chronology

Bibliography

Contributors’ biographies

Image credits

Index

Acknowledgements

Preface

Nicholas Kenyon

There are many stories told about those who have lived the unique project that is the Barbican Centre: those who designed and re-designed it in its daunting scale and complexity; those who battled to construct it, often under dreadful conditions; those who argued for (and against) its large and seemingly ever-expanding funding; those who have created its vibrant artistic and dynamic commercial programme; those who have welcomed and guided audiences and visitors; and those who have worked constantly to maintain and enhance the building. Some have hated it, some have loved it, but millions have made use of the Barbican over four decades of near-continuous activity, and have come to value its profound contribution to civic and urban life.

We have sought to provide perspectives on why and how the Barbican was created, to give critics and writers free rein to assess the centre’s programme across the years, and to provide a rich visual impression of this unique building, including much rare archive material. We do not tell a strictly chronological story, so there are repetitions and cross-references: there are accounts of the background by Robert Hewison, Elain Harwood and myself; conversations curated by Philip Dodd with those who have guided the organisation; studies of the art-forms by Fiona Maddocks, Lyn Gardner, Tony Chambers and Sukhdev Sandhu, which are interspersed with first-hand comments from some of those involved, from the plant room at the base of the building to the conservatory at the top. Roma Agrawal writes about the key building material, concrete; Theo Inglis considers the changing visual aspects of the distinctive brand.

We have not sought to impose any view, leaving authors free to make their own choices and to express their opinions. We cannot possibly cover everything that has happened; our chronology is a selective list of highlights. We take the story through the enforced closure of 2020, up to the re-opening in May 2021, to provide a context for the 40th anniversary in March 2022. The sheer diversity of the work and the contrasted approaches to the concept of an arts centre provide many different perspectives across the years, but through it all there shines one shared conviction: that any humane vision of the future must have the arts at its heart—that, if ever, is how we will build utopia.

Poster by David Hockney for the opening of the Barbican, March 1982.

Isometric drawing of the Barbican Arts Centre as built, by John Ronayne, August 1982.

Foreword

Fiona Shaw

Barbican

‘The outer defence of a castle or walled city,

A double tower above a drawbridge.’

It’s not even a lifetime ago that the Barbican opened its invisible drawbridge to the public, yet in that time the Barbican has become as permanent as the ruins of the London Wall on which it stands. The building is enigmatic — a contradiction. It is a bastion protecting the many sources of energy that create pieces of performance; yet it opens outwards with a rare power and directness.

Theatre and the arts have radically changed their nature in the past 40 years, and the Barbican has been part of that change by gathering outside influences, inviting artists from all over the world, nudging local talent to expand the methods and the outcomes of the form, expanding the range of discourse and the meaning of our work.

In a world lately battered by economic inequality and pandemic, in a moment when we have become less international than at any time in memory, the Barbican is a preserver of the multinational democracy which is art.

This democracy has been delivered as a dazzling ongoing festival, thanks to the appearances of so many great artists of our time. In my world of theatre, Ninagawa has infused spectacle with scale and feeling, Shakespeare as owned by the world and redelivered to us by the innovation and intercessions of Ivo van Hove and Thomas Ostermeier.

For me, the greatest fundamental shift in approach should be attributed to Pina Bausch. She did this in dance, without spoken language — the lifeboat that has kept British theatre afloat. Like Peter Brook, her gift to the theatre will go on resonating over the next decades as the performances she brought to the Barbican transformed the approach to all theatre. She delivered the irony of the ordinary and the tragedy of the domestic. She slowed the moment down to its essence and we saw ourselves again. The North Americans too have told their story on this stage. Laurie Anderson with her music and hypnotic abilities, and Bob Wilson who has pushed aesthetic value towards a painterly meditation. Peter Sellars, who skims meaning in his semi-staged concert operas with Simon Rattle, shows how much can be expressed in a short time, just as Robert Lepage shows us what years of process can reveal in theatrical ingenuity.

It might seem naive now, but back in the 1980s we were very fired up. The RSC expanded from the country pleasures of Stratford and came to the Barbican. When I arrived it was only two seasons old, and its early reputation among the RSC actors was as a very luxurious, but terrifying building. It was daunting. The stage door hidden like an afterthought, a mouth halfway down the ramp to the car park. Backstage we were like colts, faltering and lost on the staircases and the inhospitable corridors. The theatre covers a depth of five floors that were arrived at by a lift that took us down underground to the Green Room with its dark floors, next to that the windowless rehearsal room where we spent so much time, like canaries in a mine.

But we produced living work. We believed we were challenging outdated attitudes. Feminism had finally begun to affect performances on stage. Language, and its male values, were being questioned. It felt like a structural shift; women characters could no longer be just in relation to men as daughters, wives or mothers. The frontiers of their possibilities were as infinite as for the men. This was challenging with Shakespeare, a writer who often makes his women characters silent once they have agreed to marry, so the actress heroines of the plays carried a huge responsibility in what we were reflecting during that shifting time; politically we were influenced by the recent miners’ strike, which had left a wave of frustration and a need for rejuvenation.

The dressing rooms were luxurious, like hotel rooms. I remember in my second season some Russians were using my dressing room for a charity event. It was the day the rouble collapsed, and when I went in to see if they were all right, I discovered that in desperation they had broken my wardrobe door and liberated a bottle of whisky. They said they’d had to work hard as the wardrobe was so well made.

My first two seasons always remain with me. It was during those years that we performed Les Liaisons Dangereuses led by Alan Rickman, and Electra in the Pit — the small 160-seater that exploded with energy and brought in a new audience to discover the building with us. The seasons had other gems too. In the main house there was Ben Kingsley as Othello, and our controversial As You Like It with its abstract sets and discussions about gender and language. Who owned it?!

I remember the excitement of the first time seeing the golden mouth of the safety curtain in the main house as it opened. There is no central aisle, so there is a surprise in finding that the awe-inspiring view from the stage is reversed when in the auditorium. For the audience, the experience is one of intimacy.A season later when I was playing the ‘Shrew’, her controversial last speech — when some of the audience booed Kate’s regressive capitulation — seemed very immediate for all of us.

Decades later I returned to play on stage alone, in the one-woman dramatisation of Colm Tóibín’s The Testament of Mary — by then the theatre had the warm feeling of a much smaller house, a miracle of balanced architecture in a space that had settled into itself. I felt I was just talking with the audience. We were of one mind.

Last year, nearly 40 years since I first entered the Barbican building, I filmed in one of the beautiful hidden gardens — a secret place full of calm energy and peace. Like the theatre, music, art and cinema which it supports, it is becoming itself and transforming at the same time.

The Barbican looks to the future with that same openness and hope, not knowing what it may bring, ready to respond. It is observation and memory that makes for good theatre. The practitioners who have been able to capture their time and re-make it for audiences are the mappers of the way we see ourselves. In each time there will be new preoccupations. The theatre never lands, it just flows.

‘Serious and fine entertainment’: Creating an arts centre for the City

Robert Hewison

On 12 June 1945, in that strange space between the end of the war in Europe and the end of the war in Japan, when a Conservative government had taken over from the wartime coalition to prepare for a general election, the economist John Maynard Keynes gave a talk on the BBC Home Service, announcing the formation of the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB). Keynes was the architect of the United Kingdom’s finances, but for the past three years he had also been chairman of the Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts, CEMA, now given a permanent role in the post-war settlement as the Arts Council of Great Britain. As Keynes remarked: ‘I do not believe it is yet realised what an important thing has happened. Strange patronage of the arts has crept in. It has happened in a very English, informal way — half-baked, if you like.’ The published transcript ironically does say ‘strange’, but he meant ‘state’ patronage, signalling that, just as they had raised morale during the war, the arts had a public role to play in post-war reconstruction. Keynes declared: ‘Our wartime experience has led us already to one clear discovery: the unsatisfied demand and the enormous public for serious and fine entertainment.’

Keynes recognised that the destruction of wartime had only added to the cultural challenges the country faced: ‘We shall have to solve what will be our biggest problem, the shortage — in most parts of Britain the complete absence — of adequate and suitable buildings. There never were many theatres in this country or any concert-halls or galleries worth counting.’ He acknowledged the priority of housing, but, pointing to Russia, expressed the hope that in every blitzed town, ‘the local authority will make provision for a central group of buildings for drama and music and art.’ London, however, was a different case: ‘It is also our business to make London a great artistic metropolis, a place to wonder at. For this purpose London today is half a ruin.’

Nowhere more so than in the square mile where the Barbican Arts Centre would be built. Nicholas Kenyon describes (see here) the circumstances that led to the creation of this superb facility. Post-war reconstruction led the Corporation of the City of London to become one of the greatest patrons of the arts in the country. This chapter explores how the British concept of an ‘arts centre’ developed, and asks if the City foresaw its leading role in its development. Arts centres are not only a distinct kind of organisation, but a new building type. It is not clear that at first the City really did understand what it was doing, but the results are to be celebrated.

When Keynes spoke of a ‘central group of buildings’ as the basis of an arts centre, there were few precedents to go on. During the Depression, the American Federal Works Progress Administration had set up over a hundred ‘arts centers’, mainly in regional locations. In 1943 W E Williams, a future ACGB secretary-general, published an article in Picture Post, ‘Are We Building A New Culture?’, in which he proposed ‘a national grid of cultural centres’. These would be ‘civic centres where men and women may satisfy the whole range of educational and cultural interests, between keeping fit and popular argument.’ He may have been thinking of the Peckham Experiment, a health and social centre established in a fine modernist purpose-built building in South London in 1935. In 1945 CEMA sent out a touring exhibition, Plans for an Arts Centre, ‘designed to show how the arts can be accommodated in a medium-sized town … where it is not economically possible to run a separate theatre, art gallery and hall for concerts.’ Despite Keynes’s broadcast appeal to let ‘every part of Merry England be merry in its own way’, Plans for an Arts Centre did not have his elitist approval: ‘Who on earth foisted this rubbish on us?’ he asked.

At first ACGB supported some amateur-run arts clubs, and a single converted building as an arts centre in Bridgwater, Somerset, but as the Gulbenkian Foundation’s report, Help For The Arts, warned in 1959: ‘The terms arts centres and arts clubs can be misleading because they are used without distinction.’ Only 1 per cent of ACGB’s budget went on this area, and when W E Williams became secretary-general in 1951 and instituted his own elitist policy of selectively nurturing ‘few, but roses’, this funding ceased altogether. No one appears to have theorised much about what an arts centre might be, but in 1947 a different model was launched, the Institute of Contemporary Arts, which moved from the basement of London’s Academy Cinema into a club-house in Dover Street in 1950. In its original form it was more think-tank than arts centre, until it expanded to its present premises in The Mall in 1968, by which time the combination of theatre, gallery, cinema, seminar room, shop and café under one roof had become the standard model. The Barbican, however, would be of a different scale and order.

In 1947 there was a warning of cultural conflicts to come when the Edinburgh International Festival opened with an upmarket programme. Provoked by the dearth of Scottish culture in the official Festival, eight theatre companies, six of them Scottish, independently organised their own theatre spaces and performances. People began to talk of a ‘fringe’ of events. That Fringe Theatre was born out of opposition to official culture, with its emphasis on new work and the often improvised nature of the spaces that it used, had a long-term influence on how theatre, indeed all culture, was thought about.

After a brief Labour dawn, in the 1950s Conservative retrenchment — symbolised by tearing down all but the Royal Festival Hall on the Festival of Britain’s South Bank site — left ACGB to concentrate on ‘few, but roses’. The arts centre movement would have to wait until the return of Labour in 1964 and Jennie Lee’s appointment as the first minister for the arts. In 1956, however, the Conservative government set up an enquiry, serviced by ACGB, whose report would appear in 1959 as Housing the Arts in Great Britain. The London County Council (LCC), owner of the former Festival site, was quick to promote its plans for a National Theatre (mentioned in Keynes’s 1945 talk) and other facilities, including possibly an opera house. ACGB supported the City of London’s initiatives, and a notion of what the Barbican might be appeared in the 1959 report when it welcomed ‘a carefully planned enclave of buildings connected with the arts as distinct from the haphazard growth of theatres, halls, and galleries on the North Bank’.

Housing The Arts proposed an almost Soviet hierarchy of provision on eight levels, rising from a town of 10,000 people, which would have amateur provision only, to a region of 10 million, with every facility, including a permanent professional opera company. But there was no money. The following year a more radical conception of what an arts centre might be began to develop when the Trades Union Congress passed Resolution 42 at its annual congress, committing it to encouraging the arts. The playwright Arnold Wesker gathered a group of leftist, CND-minded supporters, including Jennie Lee (then an opposition MP) with the aim of establishing a ‘cultural hub’, Centre 42. In 1964 this turned out to be an 1847 former engine-turning shed in Camden, the Roundhouse. Wesker was unable to raise enough money and the partially converted Roundhouse had to be run on semi-commercial lines, supported by the Greater London Council, successor in 1965 to the LCC. Raves and radical theatre continued, to the delight of an audience unlikely to attend classical concerts. Centre 42 wound up in 1970, but the Roundhouse survived, undergoing its own successful transformation under the Roundhouse Trust in 1998.

The Festival of Britain site on the South Bank in May 1951, of which only the Royal Festival Hall, designed by Leslie Martin and Peter Moro with the London County Council, was preserved for the future.

Another approach to the idea of an arts centre was launched in 1964, the year that a truly imaginative conception was proposed by the theatre director Joan Littlewood, of Stratford East fame, and the experimental architect Cedric Price — the Fun Palace. This would be: ‘a university of the streets. It will be a laboratory of pleasure, providing room for many kinds of action. But the essence of the place will be its informality; nothing is obligatory, anything goes.’

The roots of the Fun Palace idea may be found in 18th-century pleasure gardens, but this was the spirit of the 60s, and, like much of that spirit, it evaporated without becoming reality. It was not one that would appeal to the planners of the Barbican. Centre 42, however, did make an appearance when in 1965 Jennie Lee published a White Paper, the UK’s first ever Policy for the Arts. The suggestion of a Centre 42 in every town echoes the Keynes broadcast of 1945, with a touch of Festival of Britain rhetoric on top: ‘It is partly a question of bridging the gap between what have come to be called the “higher” forms of entertainment and the traditional sources … and to challenge the fact that a gap exists.’

In this policy document the arts centre concept ran from ‘a single hall’ to ‘a long stretch of the South Bank’, which must have gratified the GLC, but the Arts Council’s Directory of Arts Centres continued to treat the facilities on the South Bank as ‘highly specialised and discrete buildings’. The importance of A Policy for the Arts was that it came with a 30 per cent increase in the ACGB’s government grant-in-aid, helping to establish a ‘Housing the Arts Fund’ for the first time. But this was only £250,000 to start with, far too small for a project like the Barbican. By 1970 £1 million had gone to new arts centres, which, with additional local authority funding, meant that £5 million had helped launch 125 arts centres and 26 regional film theatres. But the growth of arts centres was unplanned, usually in converted buildings, and always underfunded. At their zenith in 1986 it was calculated there were 242 arts centres in the UK; by 1996 some closures, and a narrower definition of the term, produced 129.

One centre, by then long gone, but which suggested another strand of thinking, was Jim Haynes’s Arts Lab. After running a bookshop and founding the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh — a key moment in the history of the Fringe — Haynes moved to the ACGB-funded London Traverse at the Cockpit Theatre. In 1967 he set up his decidedly not-ACGB-funded Arts Lab in Drury Lane. Focused on the avant-garde, not the Establishment, it descended into chaos and bankruptcy in the autumn of 1969, but its theatre was a launch pad for several fringe companies liberated by the abolition of theatre censorship in 1968. The idea of an arts centre had moved on a long way from Keynes’s ‘central group of buildings’, and so had the nature and demands of the culture that enjoyed them.

In 1965 a less celebrated document than A Policy for the Arts proved of equal importance to the planners of the Barbican: a report for ACGB on the state of the London orchestras by the great panjandrum of cultural policy, Lord Goodman, who was about to become chairman of the ACGB. Although the blitzed Queen’s Hall (by the BBC in Regent Street) had been replaced by the Royal Festival Hall, almost nothing had been done about providing suitable buildings for music, in London or elsewhere. Without naming them, W E Williams wrote in 1962 that there were ‘only four genuine concert-halls’ in the country. In most cities there was only ‘an antiquated barn of a hall where a boxing-bout was held last night and where an orgy of jazz is billed for tomorrow.’ This tells us something of the cultural values prevailing at the time, but the problem in London was not just too few halls, it was — in ACGB’s view at least — too many orchestras, including, with the BBC’s, five symphony orchestras. Goodman successfully proposed the creation of a joint ACGB-LCC London Orchestral Concerts Board to subsidise and supervise them, and declared that the Royal Festival Hall was insufficient to accommodate all their concert activity. One orchestra would have to find a proper home. This chimed well with the evolving thinking about the Barbican.

As Kenyon describes (see here), Anthony Besch was asked by the City in 1963 to report. In the light of the City’s hope that the Barbican hall and theatre could be ‘commercially occupied’, he recommended that both be increased in size, which inevitably affected their siting and design. The important question, from the point of view of this chapter, was who would occupy them, and on what terms? The only two viable candidates for the concert hall were the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic, and subsidy would be needed. As we shall see, the obvious candidate for the theatre was the newly formed Royal Shakespeare Company, which might be able to cover its costs, but a subsidy should ‘be envisaged’ for visiting theatre companies if the resident went on tour.

In the context of creating an arts centre, Besch’s report does not really conceive of the Barbican’s various facilities as a cultural whole, nor do the City’s documents at this period, but he was proposing to house companies of national status, a vision on a much grander scale than the mushrooming regional arts centres. Importantly, he was proposing that the City saw itself as a patron, spending between £100,000 and £150,000 a year on the arts. In March 1966 the Rates, Finance and Barbican Committees jointly responded to the Besch and Goodman reports, together with A Policy for the Arts, with this vision: ‘a true arts centre, wholly in accord with the spirit of the White Paper; an arts centre which will be looked upon as an inspiration and a pattern of things to come by other cities and of which the citizens will have real reason to be proud.’

Aware of a strong body of opinion on the Court of Common Council that objected to wasting City rates on the arts, the report continued: ‘We cannot believe that at this stage enlightened public opinion, let alone your Honourable Court, would contemplate mutilating such a fine conception by hacking off one of its two most essential elements.’ The advocates of the arts centre must also have had an eye on rival developments on the South Bank. Just as the Barbican project was championed by Eric Wilkins, the South Bank had Isaac Hayward, leader of the LCC from 1947 until it became the GLC in 1965. The idea for a ‘great cultural centre’ went back to Abercrombie’s County of London Plan of 1943, which answered the post-war Labour government’s need for a main site for the Festival of Britain. A National Theatre was the presumed centrepiece, but its site kept moving around. Periodically, a proposed opera house appeared and disappeared. The Royal Festival Hall was unfinished when it opened in 1951; its acoustics were too ‘dry’, and the need for a smaller hall propelled developments, while the Arts Council recognised London’s need for more exhibition space. In 1965 a revamped Festival Hall opened, and its audiences improved. In 1967 the Queen Elizabeth Hall and the Purcell Room opened, followed in 1968 by the Hayward Gallery. The architecture that emerged was in radical contrast to the Festival Hall, not least for being so ‘opaque’. The architectural historian Christoph Grafe asks: ‘Why was the building so heavy, so taciturn and, for many viewers, so hostile?’ These new facilities shared two features with the future Barbican Arts Centre: brutalist poured concrete and a lack of transparency to viewers. Added to this, at the time the Festival Hall itself felt opaque, in that it was only open to ticket holders before a performance.

There was another serious complication in London’s geo-cultural politics. In 1960, to the horror of ACGB and the embryonic National Theatre, Peter Hall had opened the Royal Shakespeare Company’s first London season at the Aldwych Theatre, in an apparently pre-emptive strike before the National Theatre company opened at the Old Vic in 1963. Lord Goodman was sent to Stratford to propose a merger between the RSC and the National Theatre. Although nothing ever came of it, the merger continued to be raised from time to time until 1972.

Looking across the future site of the Barbican from the north towards St Paul’s Cathedral, 1942. Amongst the rubble the trains still run, and people can be seen on the platform.

In February 1965 the RSC agreed in principle to become tenants of the theatre at the Barbican, paying a ‘reasonable’ rent. In 1968 this was set at £65,000 a year, considerably more than for the Aldwych, but regarded by the City as a form of subsidy, especially as a £12,000 remission was offered for the first five years. Hall and the theatre designer John Bury began to advise on the layout of the Barbican Theatre. The London Symphony Orchestra came on board in 1966, but as described elsewhere decided not to run the concert hall, but to be its resident orchestra. When Henry Wrong became administrator of the Barbican Arts Centre in 1970 (see Kenyon), he had a vision of which Keynes would have been proud: ‘The Barbican will be competing with the capital cities of the world to present the highest standards of music, drama, cinema and visual art, as well as to play host to the world’s major conferences.’ Still a flexible concept, arts centres were now part of the international repertoire of cultural facilities. As Christoph Grafe writes: ‘From the late 1950s until the mid-1970s they were the preferred solution for the state-administered provision of culture in Western Europe. By the end of this period … most small or medium-sized towns in Sweden, Denmark, France, Holland, Flanders and England had obtained a new building housing a variety of cultural institutions, from performance spaces to galleries and libraries.’

The Barbican was different in two ways: the provider was not the state, but a state within a state, the Corporation of the City of London, a Venice of enormous financial power, with a very small residential population. Secondly, the scale of the Barbican put it on a par with the Lincoln Center in New York, opened in 1966 — imposing but uninviting — and the Kennedy Center in Washington, opened in 1971, which Peter Hall thought ‘a pompous place, full of pretension, and very rich.’ Under André Malraux, France had developed Maisons de la Culture, new buildings exporting Parisian culture to the regions. France’s contribution to the major league was the Centre Pompidou, begun in 1971, that is to say, after the upheavals of 1968, and a building so transparent that it wears its inside on the outside.

Most large arts centres, planned in the 1950s, and long in the building, were made anachronistic by 1968. Peter Hall, having suffered a Calvary of delays and industrial disputes as bad as the Barbican’s, finally got the National Theatre partially opened in 1976. He wrote it was achieved in the face of ‘the swing against institutions, against large buildings and modern architecture, against nationalised art or industry of any kind, against expensive enterprises at any time.’ That was an accurate reading of the times; and at this point in the mid-70s the Barbican Centre was yet to be completed.

In April 1971 the Court of Common Council was asked to approve the actual construction costs of the Barbican Centre. The joint report of the Barbican, Music and Library Committees pleaded: ‘The vast amount of time and effort which has been spent on planning the Barbican Arts Centre cannot be undone … To leave out the arts centre would create a void.’ Yet they did not wish to be seen to be going too far in the cause of culture, and cautioned somewhat coyly: ‘“Arts Centre” is to some extent a misnomer’. Of the 14 elements in Phase V:

The three elements which are essentially ‘arts centre’ in nature, as distinct from the activities of a library authority, are the theatre, the small studio-cinema, and the Hall, although the role of the last two as part of a conference centre is as important as their arts centre role.

In a revealing indication of the need to reassure those members of the Court who were sceptical about all spending on the arts, the report pretended that only half of the cost of Phase V, £8.4 million, should be attributed to the centre, while ingenuously suggesting that nonetheless ‘“Barbican Arts Centre” is a convenient and well-known description.’ That compromise, or rather tacit concealment of the real purpose of the spend, was later echoed elsewhere when the City of Birmingham skilfully acquired European funding for its new Symphony Hall by referring to it only as Hall 2 of the Conference Centre.

In November 1972 the foundation stone was laid for the ‘Barbican Centre for the Arts and Conferences’. Between 1968 and 1976 the anticipated costs rose from 10 to 20 million pounds. The addition of ‘and Conferences’ was significant, for as the costs of building and running the centre rose, so did the need to offset the expense. Henry Wrong was strongly committed to conferences, and a ‘Trade and Exhibition Centre’ was inserted into the undercrofts on the north side of Beech Street. It is revealing that even at this point the arts facilities were still being considered individually; Wrong’s report suggests that such thematic planning as there might be would be driven by the need to service major conferences.

The Barbican Committee’s next battle with the Corporation was over subsidy. In 1978 Henry Wrong warned:

Experience elsewhere indicates that it can take up to ten years for a conference centre and arts centre to establish both reputation and audience to ensure the full use of the facilities … it must be recognised that the centre, during its early years, will require financial support to supplement its earned income.

He was right. He forecast a deficit for five years, from nearly £2.9 million in year one to £1.85 million in year five, with no provision for debt charges. This excluded the library and the art gallery, where exhibitions were expected to make a profit. In November 1979 the City went ahead, anticipating completion some time after January 1982. The Royal opening in fact took place on 3 March 1982, with the theatre opening to the public on 7 May.

In the 1980s, the development of the arts centre concept received a boost from Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council. Responding to what he saw as an elitist and closed-door Royal Festival Hall next to the home of his administration at County Hall, Livingstone encouraged the opening up of the RFH. An ‘open foyer’ policy transformed its previously exclusive-feeling public spaces into an all-day thoroughfare and a welcoming place for cultural consumption, with a beneficial effect on the box office. The development continued even after the abolition of the GLC in 1986: handed over in 1986 to ACGB, who were already running the Hayward Gallery, the RFH, though still operating a ‘garage’ system that simply let its halls to visiting orchestras with their own programming, became more of a unit under the direction of a new South Bank Board. The Barbican responded with free foyer events at the weekends, but did not appreciate people bringing their own sandwiches.

As the 1990s opened, the City faced challenges, both as patron of a leading London venue, and as a financial institution. Mrs Thatcher not only closed down the GLC, that same year she also encouraged the ‘Big Bang’: the deregulation of the City’s financial markets, which meant the traditional establishment centred on the Stock Exchange began to lose influence to more aggressive financial interlopers and foreign banks. Many of these moved east to a new, modern financial district, Canary Wharf. As César Pelli’s 1 Canada Square began to rise in 1988, the City fathers came to see that one way to challenge this upstart was to re-assert its cultural clout. After all, after government and ACGB, it was now the third largest patron of the arts, prepared in 1990 to write off £20 million from the centre’s building debt and commit £10 million a year for running costs. Still, in the search for a more business-oriented approach to running an arts centre, in 1989 Henry Wrong was replaced as managing director by Detta O’Cathain, who had previously run the Milk Marketing Board.

Throughout this period, the art gallery was run by a separate committee. The centre’s budget for its own arts activities was only £1 million, otherwise the art was supplied by the RSC and the LSO, when in residence, or by commercial hires to impresarios such as Victor Hochhauser and Raymond Gubbay, whose popular programming kept the centre busy and in business. To attract two million visitors a year could hardly be called a failure, but two and a half million were needed. The audience was fragmented. O’Cathain estimated that the ‘crossover’ between audiences that makes an arts centre a centre was between 20 and 25 per cent. She herself said that she did not ‘quite understand what these words a “coherent artistic policy” mean.’ It would have been difficult to achieve anyway, for neither the RSC nor the LSO were willing to co-operate. As far as Clive Gillinson, the manager of the LSO, was concerned: ‘The health of the centre depends on the success of the individual constituents’ parts.’

Unfortunately O’Cathain did not command the support of either the resident companies or many of the staff, and by 1994, press coverage of the centre’s troubles was extensive. Baroness O’Cathain demanded a statement of confidence from her tenants and the Corporation. When she did not get it, she left. The City’s town clerk and chamberlain, Bernard Harty, took over for a time, and the City then appointed John Tusa as managing director, a man of deep personal culture who understood how very large cultural organisations worked as a result of six years as managing director of the BBC World Service.

Having announced that from 1997 they would only play the Barbican for eight months of the year, in 2001 the RSC walked out completely, ready to pay £1.5 million on their broken 25-year lease. Their last performance as residents was on 25 March 2002. The Arts Council allowed them to take the Barbican element of their subsidy with them. John Tusa, who began his directorship of the centre in 1995, was bitter: ‘Throughout my 12 years at the Barbican, the Arts Council never raised a finger or offered a single pound towards our buildings or arts programming.’ The City, however, transferred their RSC funding to Tusa — and at last the Barbican began to be a coherent arts centre rather than a garage.

When a necessary plan to enhance the venues in the Barbican was refused Arts Council Lottery funding, Tusa and his team undertook a gradual redevelopment directly funded by the City to the tune of £35 million. It was not until 2013 that Arts Council England began to fund the centre’s education and outreach work beyond the Barbican walls. Meanwhile the City, now operating through the Barbican Centre Board, continued to provide the underpinning funding in the Barbican’s revenue, and gave the centre the widest artistic freedom.

The Barbican Arts Centre has emerged in a very English way: ‘Half-baked, if you like’, as Keynes described the evolution of state patronage during World War II, but organically. In spite of the time-lag between conception and construction, between construction and completion, there has been an informal development which, over time, has responded to the cultural changes between 1945 and 2022 that first built, then broke down, the Barbican’s fortress walls. ‘The post-war model has been turned on its head,’ argues its director since 2007, Nicholas Kenyon. ‘It is now much more participatory.’ There may still not be a ‘theory’ about how to create the perfect arts centre, but today, with its architectural majesty and sense of cultural confidence, the Barbican is a pragmatic answer to what an international arts centre might be, as its individual spaces and art forms have come to be treated as a coherent whole. Just as the arts themselves have sought to become more democratic, offering ‘serious and fine entertainment’ to as many people as possible, and reaching out through integrated education programmes to all classes and ages, the Barbican has become more than an expression of civic pride: a genuine public space.

The blitzed site around the Barbican area, looking towards the church of St Giles Cripplegate at the top left.

‘A fuller way of life’: The creation of the Barbican Arts Centre

Nicholas Kenyon

Why was the Barbican built? The answer is both very simple and very complex. On the simplest level, it was created from the devastation of the Blitz in order to ensure that the City Corporation had a future. The vanishing residential population of the Square Mile posed an existential threat to the survival of the Corporation, with its independent governance and long traditions, for there was a serious possibility in the post-war years that, without residents and voters, there might be a move to incorporate the City into the London County Council.

The complexities are more subtle. It would be wrong — though it makes a powerful narrative — to say that the creation of an international arts centre was part of the core concept of the Barbican from the beginning. In fact, the idea of providing world-class cultural amenities took a long time to become embedded in the thinking and planning of the scheme. Many elements came and went during that lengthy process. But eventually the commitment of the City ensured that the Barbican as a unique residential estate housed a magnificent collection of venues for culture and education: a utopian vision of living with the arts at its core.

As early as July 1952, the Public Health Committee of the Corporation was asked by the City’s Court of Common Council ‘to consider and report on the serious effects of the decrease of the resident population of the City’. The redoubtable figure of Eric Wilkins, then chairman of that Committee, had raised the spectre of the City losing its MP, and was determined to see off any threat to the Corporation. He became the leading, inexhaustible advocate for the Barbican as we know it. There were other interest groups: Sir Gerald Barry became head of an informal ‘New Barbican Committee’ to campaign for the more commercial development of the area, and the London County Council (which had acquired formal planning powers over the area in the post-war Town and Country Planning Act of 1947) was also active in making proposals. By October 1954 the New Barbican Committee had sponsored a gleaming futuristic plan by architects Sergei Kadleigh, William Whitfield and Patrick Horsbrugh; though this was rejected, it was influential on future plans as a comprehensive scheme for the area.

These were heady days for urban planning and cultural development. As Robert Hewison emphasises (see here), the growth of cultural venues and festivals including the creation of arts centres was a widespread phenomenon in this period, as the war-time Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts became the Arts Council in 1945. The opportunities offered by the widespread destruction of cities through bombing opened the potential for newly radical approaches to reconstruction, in particular for housing. In London, the City had been among the most severely damaged of all areas. The buildings around and to the north of St Paul’s Cathedral, miraculously not including the Cathedral itself, had been comprehensively destroyed, which (as Pevsner noted) ‘allowed one to walk for over half a mile without passing a single standing structure’. The question facing the City was whether to rebuild the area on the existing street plan, or to attempt a much more radical reimagining of the area. This was a debate paralleled in many British cities after the war (and had also been a much earlier debate in the City after the Great Fire of 1666). A concern evident around many new city developments was whether those who were to live there actually wanted to be there, in new tower blocks rather than old terraced streets. But the Cripplegate area of the City had been reduced to a population of just 48 in 1951 (it had been 14,000 a century earlier in 1851), so public consent was less of a factor: it was the vision of the Corporation that would be the determining element here. Pevsner and Bradley write of ‘the City’s readiness to finance the costly new housing, schools and buildings for the arts, which did not falter in the quarter-century from conception to completion’; that is a somewhat generous interpretation of the long and fraught process that unfolded.

The tensions of the early years of designing the Barbican development were not around the arts. They were rather between the pressures for a major residential development and the provision of commercial office buildings that would earn income. In both the City and the London County Council there were progressive views and traditionalist approaches vying for dominance: already after the war the City’s unimaginative planning officer had permitted, as Lionel Esher puts it, ‘some fast movers to erect, luckily not on sites of major importance, old-hat buildings of quite incredible ugliness’. The LCC architects’ department were committed modernists, especially interested in pedestrian-traffic segregation. City and LCC needed to come together in planning the new ‘Route 11’: a wide road running along the south of the blitzed site, it was to be a series of boldly angled 18-storey tower blocks of offices linked by walkways connected by bridges over the roadway. This concept could have been extended to the whole Barbican area, and an early model shows a bigger commercial development proposed by Charles Clore on the western, Aldersgate side of the site. Eric Wilkins had other ideas, and wanted to prioritise residential development.