0,98 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bluemoose Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

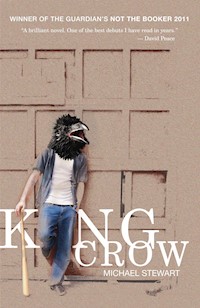

Michael Stewart is an award winning writer and playwright. In 2011 his debut novel, KING CROW, won The Guardian's NOT THE BOOKER and in 2012 KING CROW was a WORLD BOOK NIGHT recommended read.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Café Assassin

Michael Stewart

Imprint

Copyright © Michael Stewart 2015

First published in 2015 by Bluemoose Books Ltd 25 Sackville Street Hebden Bridge West Yorkshire HX7 7DJ

www.bluemoosebooks.com

All rights reserved Unauthorised duplication contravenes existing laws

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Paperback ISBN 978-1-910422-05-2

Printed and bound in the UK by Short Run Press

For Lisa and Carter

One man’s blood

is another man’s stain.

Jim Greenhalf

Contents

PUT OUT YOUR FIRES

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

THE DIET OF WORMS

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

The Shadow That Walks Behind You

22

Acknowledgements

PUT OUT YOUR FIRES

How many ways had I thought about killing you, Andrew? And now I was coming for you. I was standing in a queue, waiting. The guard was staring at me. I could feel the acid of fear and hate burning through my insides. Twenty-two years of fear. Twenty-two years of hate. I was sandwiched between a man with a mullet and a woman with a butterfly tattoo, and the guard was staring at me. I was gripped with dread. He was Saint Peter holding the keys to the gate.

He did not say good morning. Instead, he thrust a scratched black tray in my direction. I’m sure you would have got a very different reaction, Andrew: a ‘please’ and a ‘thank you’ – perhaps he would have even called you ‘sir’. No one has ever called me ‘sir’. Ever. I emptied my pockets. First money, then keys, followed by a packet of tobacco, a lighter and some cigarette papers. He picked up the papers and examined a tear in the card with suspicion.

I didn’t have any filters, I said.

Why was I explaining myself to him? I emptied the rest of my pockets. The final item was a knife. Not just any knife – but the knife. Yes, I forgot about the knife: Liv’s knife, your knife. My knife.

How could I forget about the knife? I’m sure you’re wondering, Andrew. I’d had it for twenty-two years. The guard reached into the tray and took out the knife. He held it between his massive thumb and index finger, making it look tiny, almost like a toy, certainly not a threat.

You can’t take this in, he said.

You know its dimensions, probably not even three inches long. He used his other hand to open out the tools, first the bottle opener and then the nail file. Then he turned it over and pulled out the blade. He let the blade glimmer in the harsh light.

You know how that knife can injure. You were there that evening when I received it as a gift. As I recall, you were the one who stuck the knife in, Andrew. You’ll remember the wound gushing with blood. Two towels wrapped around my hand, the blood dripping red all over Liv’s cream carpet. The blood dripping into the milk jug, fresh shock on Liv’s face.

I’m going to have to take this off you. You’ll need to fill this in.

The guard handed me a form and a disposable pen.

You’ll have to write to the courts to get it back.

Why can’t you put it behind reception and then I can get it when I leave? I said. An obvious point, I thought.

Because we don’t do that, he said.

But the reception is just there, I said, pointing to the counter.

You have to make a request in writing to the court manager. It’s all in there, he said and handed me an information sheet. Behind me the queue was lengthening and I could tell he was becoming hot and agitated. Good, I thought, let him roast.

I persisted. When can I get it back?

It’s all in there, he said.

I folded up the form and put it in my pocket. I stepped through the metal detector. It went off and immediately I panicked. My palms were sweating and my legs weak. Stay calm, you’ve done nothing wrong. Another guard frisked me. I held up my arms and he worked around my body.

Turn round, he said, and frisked me from behind.

It was the assumption of guilt. I was a crook. He was looking for a weapon but it was just my belt. I went over to the listings in the corner, looking for your name: Andrew Honour. I always liked your name, in contrast to my own which, still to this day, I despise. It seemed to be a name that was going places. A name with promise. But I couldn’t find your name on any of the lists.

There were clocks everywhere. I imagine the walls of hell are lined not with vents gushing fire and brimstone but instead with an array of timepieces. I watched them tick. I waited.

At 10am I was looking for you in Court One. A woman in her forties was crying, her mascara running down her face in inky rivulets. It was the woman I’d seen in the queue with the butterfly tattoo. The man with the mullet was hugging her as he ushered her in to the court. I sat down in the public seating area. Four men and a woman in black gowns and wigs were standing at the front clutching files tied with ribbons. One of the men was on crutches. They looked like a gathering of hooded crows. I scanned their faces. None of them looked like you, Andrew, as I imagined you after twenty-two years. The same age as me, forty. Fat? Bald? Grey? It didn’t matter. I’d know you as soon as I saw you.

What happened? said the woman in a wig and gown to the man in a wig and gown on crutches, gasping in mock-horror.

Skiing, he said, and mimed the action of skiing with the crutches, scrunching his face up in what he clearly felt was an amusing way.

Oh no! You poor thing, she said.

The woman with the butterfly tattoo was sitting down now, still crying. The mulleted man was still trying to console her. The judge entered, we stood up. He sat down, we sat down. I wonder why these people never get shot. It would be easy to do, wouldn’t it? All the fuss over security at the door and yet they walk out of the building unguarded – almost asking for a bullet.

Are you Jamie Turnbull? the clerk to the court said to the man in the dock. For a moment, I thought he was addressing me. I wanted to stand up, plead my innocence and tell him he had the wrong man.

I am, said the man in the dock.

A guilty plea for dangerous driving. Dangerous driving – I almost laughed. That’s not a crime. That’s just over-excitement. The judge seemed impatient, even though they’d only just started. Probably anticipating lunch in one of the fine eateries that surrounded the courts.

I was wondering whether other barristers would be involved. What was the best thing to do, sit tight and wait for you, or move around and risk missing you? It was a dilemma. I decided to sit it out. What would I do when I saw your face? Would I be able to resist putting my hands round your throat and squeezing the life out of you?

Jamie was imprisoned for nine months. Next was a robbery. The boy standing in the dock barely looked eighteen. He’d gone up to a student and asked him for the time, then he’d grabbed his phone and punched him in the face. The student ran away, but this lad, who caught up with him, dragged him to the ground and then kicked him repeatedly in the face. In the face, Andrew, in the fucking face.

He was given eighteen months in a young offenders’. I left the room and walked across the hallway to Court Two. Perhaps this was where I’d find you, Andrew.

Vinnie Howell, commercial burglary. Vinnie was a smackhead but he’d been off opiates for three months, according to his legal representative, who also wanted it known that Mr Howell had served queen and country in the armed forces. I scrutinised the barristers in their archaic raiment. They were not familiar. Surely a man cannot change beyond recognition? Had I changed? I still had the same build, though I supposed I’d filled out a bit – I hadn’t overdone the weight-training but still, it showed: thirteen stone. Waist: 32. Chest: 46. Neck: 16. No grey hair. No receding hairline. Forgive me, Andrew, for rubbing it in.

Vinnie Howell was fined and given community service. He seemed relieved, the tightness around his shoulders eased. The expression on his face was one of defiance. He had a tattoo on his arm, I couldn’t make out what it was. He pointed to it and stared at the judge with even greater defiance.

Next up was another smackhead; the one after him also a smackhead. What was the judge’s drug of choice? Port? Cuban Cigars? Brandy? Champagne? Vintage wine? Cocaine?

You were not there, Andrew. I stood up again and left the room, making my way to Court Three. Another commercial burglary. Another smackhead. It was 10.57 and still no sign of you. I went to the next court, Court Four.

This time I thought I saw you, but it was hard to tell from where I was. It was your profile. The same straight nose and weak chin. But there was too much reflection from the screen separating the barristers from the public. I saw my own outline projected onto the glass like a ghost. I could see the court beyond but it was hard to make out the faces, just the wigs and black gowns.

Perhaps you liked wearing the costume, Andrew, in the same way some people enjoy fancy dress parties, or dressing up as the opposite sex. The barrister spoke. He had a Belfast accent. It wasn’t you. Bollocks.

How many times had I thought about killing you? How many ways? Killing you was the easy part: knife, rope, gun, poison, a staged accident. Perhaps the most satisfying would be to kill you with my own hands and watch you gasp your last breath. There were no end of ways. The difficult part would be getting rid of the evidence. I could dig a grave and bury you deep in the earth, let the worms feast on your flesh. I could use acid to dissolve your corpse. I could feed you to the pigs – apparently they leave only the hair and teeth. I would then burn the hair and grind your teeth into a fine powder. There would be nothing left of you. No trace whatsoever. But some time ago now, I cooked up a better plan.

I was feeling queasy. I hadn’t found you and I didn’t want to give up on you, but I was finding it hard to breathe. My chest was constricting, nausea building. There were another seven courts to go, but I was not going to get round them in an hour. I could come back another day. It wasn’t as though I had anything else to do. I went downstairs and out the door.

I stood near the entrance of the courts, breathing deeply. I leaned against the concrete wall. I was trembling, lightheaded, as though I could pass out at any moment. I needed a cigarette. I used up the last of my tobacco as I rolled one and lit it. What now? I sat on a wall on the other side of the road and waited. I read the form I’d been given by the guard. To get my knife back I would need to make a request within twenty-eight days. I put the form in my pocket.

After a while, they started to come out of the building: the men in pinstripe suits pulling cases on wheels, the cases filled with gowns and wigs and bundles of files tied with ribbons. They all had short hair, they were all well groomed. But none of them were you.

Then I saw you. I couldn’t quite believe my eyes. Was it? Yes, it was – it was you. And you were walking towards me, pulling your case. Hair thinner and greyer, face fuller. You were wearing glasses and you had a paunch, more jowly, your neck thicker, but it was unmistakably you. I pulled my hood up, moving back into the shadows. Out of the two of us, you’d aged the worst. The extra weight around your cheeks had made your cheekbones lose definition and your weak chin was weakened further by the flab beneath. The beer belly didn’t suit you at all. You didn’t have enough muscle on your shoulders to carry it off – it turned you into a pear. I was by far the superior specimen. And that knowledge filled me with joy.

I waited for you to pass, then followed some distance behind, up the road. We walked a quarter of a mile. At one point you turned around, but you didn’t recognise me. Why would you? I was just another man in jeans and a hoodie – one of the invisible people. A shadow.

Eventually you arrived at your chambers, climbed the steps at the entrance and disappeared inside. I waited for you. What now? How long would you be in there? Perhaps that was you done for the day. Would you go straight home? Would you have a game of golf? Surely not golf. Please don’t let him be a golf player, or someone with a yacht, I prayed to a dead god. It must have been nearly an hour before you reappeared. You made your way to a Jaguar and drove off.

A car. I should have thought of that. I was convinced you’d take the train. I’d pictured you in first class, reading The Telegraph or hunched over case notes, with a servant pouring another espresso. I should have driven across in my dead dad’s car, but after all this time there was no sense in rushing things. I would go back to my new flat and write to the court. I would get my knife back. The main thing was, I’d found you.

2

The next day I did a hundred press-ups, a hundred sit-ups and five minutes of shadowboxing. I showered and dressed, had toast and scrambled eggs, half a cup of black coffee. When I got to the job centre it was already busy with those signing on and those making fresh claims. I sat on one of the newer-looking chairs.

It was all new to me, my first time in a job centre. They used to call it the dole office, or the DHSS. Now it was called ‘jobcentreplus’. A single lowercase word with ‘job’ and ‘plus’ in white and ‘centre’ in yellow with a background of verdant green, to make it appear fresh and wholesome, a living thing – it was certainly thriving.

A voice, crackly with interference, announced the next claimant.

Nicholas Smith.

I stood up with more forms to fill in, boxes to tick, walking over to the illuminated desk.

It’s Nick, I said.

I’m sorry?

The woman was facing a computer screen. She was dressed neatly and was tapping away at the keyboard.

Please, call me Nick.

For the first time she looked at me. Her eyes gave nothing away. She wasn’t bad looking. Medium-length straight brown hair, probably in her late twenties. Her low-cut neckline was just on the right side of respectable, so that your eye was tempted, yet at the same time you blamed yourself for looking.

Have you filled in the forms?

Most of them.

She took the forms from me and started to leaf through them, ticking some of the boxes in the ‘to be completed by staff only’ columns.

What do you do?

Do?

Was this to be an existential enquiry? I wondered.

What is your normal employment?

Oh, I see. I’d anticipated this question, rehearsed my response in my mind many times, but still it jolted me. I shrugged, Whatever’s going. I smiled at her but she frowned.

Office work or manual work?

I don’t mind.

Any qualifications? She turned back to her screen.

It’s all there, I said, pointing to the form. She read on.

So you’ve got two degrees, one in English and one in Combined Social Sciences?

Yes.

From the Open University?

That’s right.

She looked at me again, as though searching for something. I smiled back. Was I more acceptable to her now she knew I was educated? Perhaps I was more qualified than she was and she resented this.

Do you own any land abroad?

Let me think … No.

Do you collect a war widow’s pension?

I leaned back, not in a cocky way, I hoped, but an endearing one. I smiled again.

Well? she said.

I mean, what do you think?

She tapped something into the machine.

Are you a share fisherman?

A what?

A share fisherman.

I’d never heard of a share fisherman.

You don’t own your own boat?

Correct.

Look, it may seem like a silly question but I have to ask it.

That was the nature of her employment: to incuriously ask strangers farcical questions. She tapped away for some time. I looked around. The room was still full but quiet, like a library without the books.

How much are you prepared to work for?

I turned to the woman again, Money? I don’t know. What’s normal?

She glanced at me once more. Perhaps my question had seemed sarcastic but that wasn’t my intention. I attempted a smile but she had already turned away.

I meant the minimum … per hour.

I was surprised by this question. I’d expected them to dictate this. I don’t know really. How about ten pounds?

The woman seemed vexed. She pinched the top of her nose. You’ll severely limit your ability to find work.

I sat back in the plastic chair and recalculated the sum. How about a fiver an hour? How does that sound?

The woman turned from the computer and confronted me across the table. The minimum wage is set at £5.93 per hour for workers aged twenty-one and over.

How about £5.93 then?

She tapped again at the keys and then hit the return button. You’ve not filled in some of the information regarding your previous employment.

I’d been preparing for this. I’d rehearsed my answer and was playing it over and over in my head.

You did the first two years of a fitting apprenticeship at a motor factory.

Yes.

But that was twenty-two years ago.

Yes.

Well, what have you been doing for twenty-two years?

I felt tired. The invented scenario in my head was still playing. Several years abroad, working in Spain in a bar, café work in Amsterdam, picking grapes in France, then years of self-employment as a handyman, but it all went out of my head and I just came out with it.

I’ve been in prison.

For twenty-two years?

Sort of, yes. One way or another.

What for?

It’s complicated.

Go on …

I looked at her.

Yes?

Murder.

She stopped tapping at the keyboard and looked away from her screen. She turned to me. She didn’t say anything, just looked at me and narrowed her eyes, as if I was something she was trying to read from far away. Did she perhaps think I was joking? She raised her eyebrows, staring at me with renewed interest. Not horror, or even fear, just curiosity.

Don’t suppose there’s anything on your system for murderers, is there?

Outside the sky was bright grey. The air in the job centre had been dry and sterile and I was thirsty. It was only ten o’clock but early enough for the pubs to be open. One of the noticeable differences. You might think that I would have been more at sea in this new world, given the length of time I had been away. But you get to watch a lot of television inside and there are new people coming in all the time, so I was prepared for most of the changes I encountered. But pubs opening at eight in the morning was not something that had occurred to me. It was a welcome novelty. I bought a newspaper, rolling tobacco and more Rizlas. I walked through the city centre.

It was March, cold but crisp, clean on my skin. I’d shaved a few hours ago and the chill tickled my cheeks. I walked beneath the inner ring road, via the subway. I skipped over a rivulet of piss intersecting my path. The air was tangy. It wasn’t a particularly salubrious scene or indeed an inviting one, but this was freedom and, although freedom stank of piss and incarceration stank of piss, this piss still smelled sweeter than prison cell piss.

The landlord was just opening up. He nodded ‘hello’ as I approached the bar. A plump and friendly barmaid served me a pint. I sized her up. It was good to gaze on a real woman and not the uniformed simulacra of womanhood the female screws represented. I sat in the corner. There were already a few postmen at the bar and some old alkies in flat caps and oil-stained overcoats. I drank from my glass and, for a moment, I felt normal.

Beer is the one thing you can’t get inside. Some prisoners attempt to brew their own beverage. The preferred method is to use orange juice, sugar and cream crackers (for the yeast content). The result is a very unpalatable, albeit lethal, ‘poteen’ style concoction. You can easily acquire skunk, crack, smack, Valium, Mogadon, Subbies, any drug you like, but a pint of real ale … I’d fixated on it many times. I would close my eyes and I’d be there at the bar, some curvaceous barmaid with plenty of cleavage pulling the pump. The froth flowing over her hand, like some cheesy beer advert. A pathetic male fantasy, but the sort that’s necessary when you’re banged up and clinging to the fine threads of your sanity.

I took hold of the glass and consumed the beer in four sups. I went back for a refill. How do the purveyors of alcoholic beverages view their clientele? With pity, scorn, disdain? Rarely with affection. But they should reassess this relationship, for what they sell is all the goodness of the world. That pint of beer tasted to me of laughter and innocence. It was golden and glowing with life. Like an eighteen-year-old girl dancing and singing, spinning round, her hair bouncing, her eyes sparkling. I was thinking of Liv. A mess of black hair down over her shoulders, smoke-grey eyes, framed by thick black eyeliner. Curves, calves, clavicles.

The TV was on in the corner. Twenty-four hour news. Bombs, tanks, Libya. Gaddafi railing against foreign imperialism. He looked confused. A few months ago he’d been laughing and drinking champagne with the very people that were now dropping bombs on his head. You’ve got to watch that. Your enemy is the man standing next to you, smiling. Your enemy is the man who pats you on your back and says, well done, mate. Your enemy is neatly dressed in a charcoal suit, a plain tie and a crisp white shirt.

The footage changed. Cuts. Cuts in spending. Police, the arts, the NHS. No one escaping the axe except the bankers and the barristers. There was an anonymous suit trying to justify funding the arts by explaining how it feeds the economy. I can tell you how to justify it. You justify it like this: first, picture a man locked inside a white concrete box, with a bright light in his eyes, with no sense of hope. Picture this pitiful creature lying on his bed, repeating a line of poetry over and over again. Why is he doing this? He’s doing this to feel human. He is doing this to feel connected to something outside of his own hell. He is doing this because if he doesn’t the water will pour in and he will drown.

Rising crime, rising unemployment. An old man in a flat cap nursing a half, turned to me. It’s like the eighties all over again, he said and stared at the screen.

There was a band on the radio sounding just like The Pixies. He was right, the eighties all over again, and I was transported in my mind to that club on that night.

You were at the bar, Andrew, and I was dancing with Liv on the floor. She was wearing the red and blue polka dot dress with the white collar, which made her look both chaste and filthy at the same time. It was The Pixies song, ‘Debaser’. And I was singing along, ‘I want to grow up to be, be a debaser’. Liv was joining in. ‘DEEE-BASER!’ The whole club was moving to the manic beat. Her eyes were sparkling, her hair was shining, her skin was glowing. I was careful not to get too close to her. I kept looking to where you were standing by the bar, but you were busy chatting to someone. It was meant to be just me and you. Our last night out before you went to King’s College to study law. A goodbye blowout. But we were predictable. We were eighteen and there was only one club we went to, and that happened to be the same club that everyone else in our social circle also went to.

The Hacienda was for estate scallies in designer tat and over-styled haircuts, or middle-class students pretending to be estate scallies in designer tat and over-styled haircuts. I always hated Kicker boots and baggy jeans. I hated those over-sized long sleeved T-shirts with a smiley face and ‘aceeeeeed!’ printed across the chest. We would look at the queue of clones outside and go next door instead, down the stairs, following the fog from the smoke machine, following the bass from the sound system, submerging into the comforting dark of The Venue.

We’d shared a small bottle of Southern Comfort on the bus. We’d had a couple of pints in the Britons Protection, and now we were coming up on a pill. We weren’t very experienced in the world of illicit pharmaceuticals and this was, if I remember correctly, only our fifth or sixth time. We were starting to feel the music tingle and the warm feeling spread right to the tips of our fingers. I couldn’t take my eyes off your girlfriend. I wanted to touch her skin. I wanted to kiss her flesh. Euphoria, wave after wave. Over and over. The eighties, cuts, cuts, cuts, Gaddafi, Gaddafi, Gaddafi, Ecstasy, Ecstasy, Ecstasy.

I sat back, warm in the memory, warm in the glow from the second beer. I looked back to the old man. He was staring at the TV. Two postmen were chatting in the corner. I looked over at the barmaid, taking a steaming glass from the washer and placing it on the shelf above her, enjoying watching her arm stretch up and her cleavage rise above her top. I rolled a cigarette, put it to my lips and lit it.

Immediately, the landlord rushed over and grabbed it off me. It wasn’t 1989, Andrew, it was 2011, and smoking in public houses was outlawed. You could smoke in prison but not in pubs. You could smoke in the bar of the Houses of Parliament but not in pubs. Prisoners and politicians. Criminals and crooks. Only the damned are given licence. You can smoke all you like in hell. I looked over to the door. The door was open. It was something I kept having to remind myself. The door was open, it wasn’t locked.

I stayed for one more drink. I wanted to bask in this state of having found you. I surreptitiously glanced at the barmaid’s supple body and glistening flesh. I imagined her with no clothes on. Desire is both wonderful and terrible: it charges you with hope, it chokes you with despair.

I spent the rest of the day wandering round the city, mesmerised by all that was new and immersed in the life around me. Back at my newly rented flat I made myself a coffee and sat at the Formica table. The floor was in terrible condition and a new patch on the ceiling indicated that there had been a leak. I listened to the deafening hum of the fridge. Why was it so loud? I turned on the radio to block out the sound and listened to it for a few hours. I rolled a spliff and smoked it down to the roach. Dark outside but it wasn’t late. Probably no later than ten o’clock. A bit stoned, a bit pissed. Just the radio for company. I decided to go for a walk.

It was dark and cold. I wandered down each narrow snicket, passing the backs of people’s houses. As I wandered, I could peer into their lives. There was a couple, their kids probably already tucked up warm in bed. She was in a bathrobe, he was in tracksuit bottoms and vest. They were snuggled up together on their sofa, staring at the screen that lit up the room and made their faces glow.

I passed a house with a conservatory. In the living room, a man slumped in an armchair was watching a large plasma. In the conservatory, a woman slumped in an armchair was watching a smaller plasma. They were like a diminishing reflection of each other. Their wedding album on the shelf, unopened, collecting dust. Down another snicket, different houses, different windows, same images. Through a ginnel, terraced houses, kitchens.

I stopped to watch a man at his kitchen window, washing up. He placed a white plate in the sink and scrubbed at it with a green and yellow sponge. It was a simple action, but it captured my attention. He took another plate, removed the grease and made it clean. I could see the dignity of being alive, being free, independent. I watched as he took each item of crockery, submerging it in the foaming water, cleaning it with a sponge and then stacking it on the plastic drainer. He took a towel and wiped his hands, carefully dabbing between his fingers and the edges of his nails. The job was done. He seemed satisfied.

A woman entered the room and walked up behind him, putting her arms around his waist. He turned to her and they embraced. This image of them entwined was framed in the window, backlit by the kitchen light. I watched them until they broke off from their embrace and left the room, switching off the light as they went, creating a black screen. I couldn’t get the image out of my head. My whole body ached. I felt sick with longing.

I came to the main road. I could see something skulk in the distance. It looked like a fox, slinking across, but as it got closer I could tell that it was a dog. Startled, it ran into the road. A car screeched round the corner, clipping the dog, sending it flying up and onto the pavement. A dull thud as it hit the flags. The car drove off, the driver perhaps unaware of what he had done. I chased after the car, but it had gone. I went back to the dog.

It lay in a heap on the pavement, eyes looking scared. It wasn’t wearing a collar. There was blood pouring from its back leg. I picked it up – it wasn’t heavy – and carried it back to the flat. I laid it out on a blanket. It was a male. I examined him. He didn’t seem to mind. He let me feel him all over, as I checked for broken bones.

He seemed unharmed apart from his back leg. I bathed it with a cloth and warm water. It wasn’t broken but there was a deep cut that revealed the bone beneath. I cleaned the wound and bandaged it with a clean rag. I looked in his eyes again. Trust.

Are you hungry?

I took two cereal bowls from the cupboard above the sink, filled one with water and emptied a tin of tuna into the other. I took them over to where he was lying but he didn’t show any interest. He was probably too exhausted to eat, or in too much pain. I propped his head with a pillow and put some of the fish onto my palm. He fed from my hand. I kept doing this until all the tuna was gone. Then I took the pillow away and let him lie back on the blanket. It was hard to tell his age, but he wasn’t old. He was slim, with plenty of muscle under his hair. He had done a lot of running away. I felt scabs along his back. He’d done a lot of fighting.

There’s a good boy.

He needed a name. He looked like a fox so I called him Reynard. Ray for short.

I stroked him, There you go Ray, you’ll soon feel better.

He’d only just met me but it was there already. Trust. It’s something you lose over time. Bit by bit you lose it and then there’s nothing left, is there, Andrew? It was important that this dog didn’t lose it. Trust.

Outside the wind was blowing refuse around. A can clattered down the street. I closed my eyes and in my mind I was clutching a pestle and mortar. I was making a powder by grinding your teeth.

You are playing pool with a man who murdered his best friend with a hammer. His name is Philip Heggerty. You are in Gartree prison in Leicestershire. This is your final spell of incarceration. You are surrounded by killers: religious killers, contract killers, domestic killers, binge killers, nice killers, rich killers, poor killers, police killers. You have been to see the senior forensic psychologist, Stephanie Simpson. She has really helped you come to terms with what you have done. You just wanted to thank her now you have been given the all clear. You are old mates these days.

You have just seven-balled Shaun Gibbs who killed a woman by strangling her, a woman he had only just met in a kebab house. He followed her to the park, murdered her, then handed himself in. He is autistic and finishing off a degree in pure mathematics. Everything you do is being watched and everything you do is being judged. But it no longer matters. You smile at a closed circuit camera.

You have been in prison longer than you have been out of prison. There is a certain amount of respect for you now. You’re a veteran. You have your own cell. It is a small room but you are allowed to put up posters. You have covered the walls with pictures of dead poets. Only the back wall is still bare. You are not allowed to put posters up on the back wall in case you do a ‘Shawshank’. You have a budgie called Baudelaire which you keep in a cage. Sometimes you let Baudelaire out of the cage so that he is free within your cage.

You were given a tariff, a minimum number of years you have to spend in prison before you will be considered for parole. You were given this tariff a long time ago and you are nearly at the point of being eligible for early release. You like thinking about this. You can see the time ticking down in your skull. You can see yourself walking down a city road. You know exactly where you are going. You know exactly who you want to see. You picture this person in your mind. But this is replaced by another image. An image you don’t want to see.

Instead, you concentrate on the yellow and the red balls. You like the yellow and the red balls. You like the way the green baize of the table offsets the colours of the balls and intensifies their hues. You like the white ball, isolated and yet at the centre of everything. You focus on the black ball. The black ball unnerves you. It is like you. Inside of you is a black ball. The black ball inside you is a secret. The secret is black and hard and densely packed.

You have read somewhere that pool balls used to be made of celluloid and could explode at any moment. Celluloid is a volatile substance. Your secret is made of celluloid.

In Gartree, prisoners are only locked in their cells overnight and at lunch times. During the day you are expected to keep yourself busy with education, exercise, or work. You are even paid for your work, and you can spend this money on luxuries, such as CDs, books, or treats for Baudelaire. It is not a tough prison, despite being full of murderers.

You have decided to do the rest of your time on your own. No more complications. You are over that now. You can beat it by yourself. You pocket one of your reds and snooker Philip behind another. You watch Philip pot the white ball by mistake, giving you two shots again. But you are not going to pot the black ball. You are going to let Philip win this game because, unlike Shaun, you understand what Philip Heggerty did.

3

An old fucked Ford, a few hundred quid, a battered guitar and a rusty tool box. That was all he left me when he died. The old fucker. The old fucker hadn’t worked for years. Council house. No family, no friends. Just a few old winos down the local for company. You’ll remember that he was a plumber by trade, self-employed, had his own van with his name and number on. But he was done for drink-driving and lost his licence. Don’t know if we ever talked about the ins and outs of it. I remember you calling for me, standing in the back yard, afraid to come in, or knocking on the front door so quietly I could barely hear you.

He’d sit at the dining table massaging his temples, staring off into the distance. You didn’t dare enter the room when he was like that. Neither did I. Best to stay well clear. The drinking got to be a real problem. By the time of my trial he was rarely sober. The only thing that would wake him up was a boot in his bollocks.

As I grew taller than him and he grew more inebriated, the tables turned. I was no longer afraid of him. I looked down on this mess of a human being. But now his money, his guitar, his toolbox and his car were my only possessions. The car hadn’t been driven for months. He’d won it in a bet a few years before he died. No tax, no insurance, no MOT. It took me the best part of the morning to get the engine going. Two years as an apprentice fitter in a motor factory. Some of those skills were still there. Eventually the pistons turned over and it choked into action, just like my old man used to do.