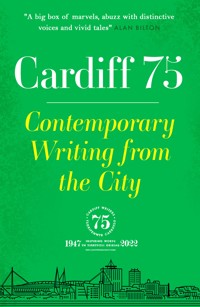

Cardiff 75 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

'heartily recommended, and a really, really good book for dipping randomly into, as well as of excellent quality all round.' – Mab Jones, Buzz 'A big box of marvels, abuzz with distinctive voices and vivid tales. This is dazzling testament to the ability of Creative Writing groups to energise and inspire.' – Alan Bilton 'Down-to-earth at one moment, the next fantastical, humorous or heartfelt, nostalgic or raw, and yet hospitable, grounded in locality but with connections open to the wide world' – Philip Gross Some collections serve to mark particular events or milestones, whilst others contain work of the highest quality. This collection manages both of these things, with 75 pieces of poetry, creative non-fiction, and short fiction by local writers celebrating 75 years of creative writing in this fabulous city of the arts. Cardiff Writers' Circle was formed in 1947 and is joined here by other local writing groups, all lending their imaginations to a wide variety of styles, genres, and formats. Poignant, playful, satirical, and acutely observed, this anthology is a showcase for the fantastic talent that exists today in Cardiff, city of the dragon.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 237

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

Cardiff 75

Contemporary Writing from the City

Edited by Sara Hayes, Paul Jauregui and Martin Buckridge

Foreword

It is my great privilege to have been chair of Cardiff Writers’ Circle for seven years; especially in this our seventy-fifth birthday year. (No, I wasn’t at the original meeting.) And many other local writing groups have joined with us to celebrate seventy-five years of creative writing in this city. We have held open mic evenings, a large writers’ gathering at a city centre hotel, a seventy-five-word flash fiction competition, and a series of free tutorials presented by professional tutors, on many aspects of writing, presenting and publishing work. To cap this fantastic year off, and with our friends from the other groups, we are publishing this collection of seventy-five works, one for each year of creative writing in this fabulous city of the arts. Here you will find poetry, short stories, flash fiction, haiku; with almost every genre and style represented. We intend to continue this co-operation between groups with more projects and events, to encourage more people to take up their tablets, laptops, pens and paper, quills and vellum, whichever medium they prefer, and just get writing.

I hope you enjoy the works gathered here. And suggest you look out for the next collection – Cardiff 150.

Paul Jauregui Chair of Cardiff Writers’ Circle October 2022

Preface

On 4 May 1947 eleven keen writers met in the Technical College in Park Place and agreed to launch Cardiff Writers’ Circle. Seventy-five years on, the Circle is still active, the oldest continuously running creative writing group in Wales and one of the oldest in the UK. The group currently meets on Monday evenings at the YMCA in the aptly named Shakespeare Street off City Road, when we read and discuss our own work.

The Cardiff 75 project marks this anniversary, celebrating seventy-five years of creative writing in the city. Starting in July with a Writers’ Gathering attended by local writers, publishers and speakers, other activities have included Saturday morning workshops and open mic sessions in the Flute and Tankard. Publication of this volume marks the final stage of the celebration.

Cardiff Writers’ Circle is indebted to the many friends who have contributed time and energy to make connections between writing groups and support each other’s writing.

Particular thanks go to Sharif Gemie who helped significantly in bringing this collection together. In addition, he has researched our records and interviewed members past and present to tell the story of our first 75 years in ‘A History of the Cardiff Writers’ Circle, 1947—2022’, which can be downloaded free from:

https://cardiffwriterscircle.cymru/a-history-of-cardiff-writers-circle-1947-2022-by-sharif-gemie/

His short play written for the Writers’ Gathering, ‘2022 to 1947 – A Backwards History’, is included towards the end of this collection. vii

Cardiff 75 is a unique collection of seventy-five previously unpublished contemporary short stories and poems from the city. Contributors have diverse backgrounds and life experiences; they are from different writing groups or none. A few may be known to the reader, some have previously been published, others not. The common denominators that bring them together are a love of writing and a personal connection to Cardiff.

We are deeply grateful to our publishers Parthian and to Viridor and Prosiect Community Fund whose generous support has enabled production of this book.

Martin Buckridge Sara Hayes October 2022viii

Contents

The Bone Layers

WinneroftheCardiffWriters’Circle Short Story Competition 2022

Katherine Wheeler

It’s hot. There’s a stickiness to the air – half sweet, half threat – and the boys have come to join their fathers in the bone yard.

It is this time of the year that the boys age up from play fighting and class scuffles of their schools and take on a trade. There are many new apprentices who are donning their work coats and trowels for the first time.

It is easy to forget that construction is a job. It is mindless. It repeats layer upon layer. The mortar is mixed with sand and water, spooned onto the edge of a trowel and the mixture patted into an even paste, upon which the long bones will be placed. Many of the men stay until retirement, the grind of the day is something they can teach their hands. The callouses equalling trophies of their great and worthy work.

Everard’s son is not used to the heat of the day and hides from the sky underneath his father’s coat. Like the other boys, it is his first day. His clothes are ill-fitting, the cuffs hang past his fingertips and his boots slide loosely around his feet. He and his father have the job of hauling the bones from the stocks and placing them on top of the mortar. Everard’s son will lay the corners, his father, the connecting walls.

“A corner piece is the most important of the house,” says 2his father. “For those, each part must be angled just so. It is the biggest job of them all.”

The boy is given a piece to feel, to see how it weighs in his hands. It’s light, easy enough to balance on the crux of a finger but weighty enough to shatter. The sweat on his palms is enough to slick the white until it shines against his skin. With it is a sensation, he feels it spinning around his head and ears. There’s sickness in there, a sweet heady dancing of his thoughts.

He hands it back to his father, the surface leaving a white coating on his palms. The boy looks down at his arm, grabs around the flesh and to the harder tissue underneath. It is a straight line.

“How is it curvy?”

His father doesn’t answer.

“I can bend sticks easy,” the boy offers. “These are so powdery and weird.”

“If you put it on right the first time, you won’t have to adjust it. It dries fast. Look, I’ll show you.” The man scoops a trowel into the mortar and spreads a thick layer onto the bone. “Like this.”

He places it down and the wall grows an inch higher.

“…and then you do it again?”

“Again and again. Until you have a house.”

When the day is over, Everard’s son walks along the docks. The sun hangs sharp orange fingers onto the horizon, its rays spread across the water. It is still hot outside; the scorching heat of a spring day burns the air. It is easier to breathe than earlier but the warmth still plants an ache in his throat.

He has never been this way before; it is a path reserved for only a few. It is usually empty, the ships along the water often deserted. Now he is learning a trade, he can walk where he is 3allowed. When the boy had peered in before, he had seen farmers, brandishing new tools and heavy bags behind them.

He walks for a while, counting ripples in the water, when the path stops. There is the left turn and a right – leading to the hay market and to the sea. The boy turns around, doubles back down the dockside path. He’s gone too far to turn off so he follows the path beside the water’s edge.

There’s a ferry boat cruising past a small distance away. The boy squints at it. The captain is missing from the cab but there is a thin trail of steam from the funnel atop it. He stops, pausing until the boat passes the gleam of the sun, and looks again. The boat is large, the same brown as the waveless water. There’s a square platform at the back populated by a group of silent figures. Some are lying on their sides, knees splayed out, folded into wordless L shapes. The others are bent, like they are caught in a bow. A few are walking from side to side, fingertips grazing and skimming the floor. They scutter wordlessly, unconscious of Everard’s son, a few mad eyes darting to spots on the water.

He watches the boat cruise out of sight. The sun is nearly down and the water a drastic orange. When he walks here again, he’ll watch out for the boat and the bent-double people.

Everard’s son walks the path home and drinks the soup his mother gives him.

The next day is hotter than the first. It aches to move but the men in the bone yard stamp across the yard like tanks. The boy has been tasked with carrying the finer bones whilst his father does the heavy lifting. It is nothing-work, the kind he’s already done in the schoolyard, but the ache of the daytime pierces through him. It is too hot. Too oppressive a day for being out in the open air. He slumps back against a heap of rubble and tips his head back… 4

One of the men screams from across the yard. The boy scrambles upright, scurrying to attention before the man seizes his arm.

“Keep moving, boy! For God’s sake!” the man shouts. “Were you slouching?”

The boy squints at the question. A drop of sweat falls to the corner of this mouth and trickles down like spit. He looks around, his father is nowhere to be seen.

“Answer me!”

He looks back, up and then nods. “It’s too hot. To work, sir.”

“You will not slouch in the heat. Tomorrow you will carry the big bones.”

The boy nods again. He will have to swallow the heat and keep moving.

When the day is over, he walks home along the docks to see the flat boat again but the water is empty and brown.

The third day it thunders. The yard is showered with tropical rain which hammers hard enough to pick the sand from the ground. The boy finds himself dragging his feet through puddles, the relative coolness of the water easing his scorched toes. He manages a steady pace, trying some of the bigger bones with less mortar this time. The walls of the house are getting bigger and for every side built up, there is another corner-piece to set. He handles two over the course of the day. The pieces are ridged, but set hard into right angles, like they would curl if they could. He remembers his father’s instructions – a little mortar spread along the underside of the piece, laid down and left until set, you must measure the angle or the piece will go to waste.

“Well done,” says one of the older men. “You learn fast. Too fast.” He laughs, but the sound is tinged with a hollowness. A few of the other men join in, voices absent. 5

Everard’s son thinks of the boat and its passengers. They hadn’t noticed him, though the waterside was otherwise deserted. The boy wonders if they had been taking a ferry or ducking for a low bridge. Perhaps divers readying themselves for harbour swimming.

On the fourth day, he finishes a side by himself, sneaking a moment to rest out of sight where he can. The men make examples of themselves whilst he’s looking: shoulders back, heads poised and knees bent when they lift. His father too, with a tight smile.

The fifth and sixth days go much the same, the walls building higher and higher until the men are working on ladders.

Everard’s son notices his father sitting as they climb, basking in the shade of the workmen’s cabin. He is not slouching. Is that why the men are not shouting? He has a drink too, the bluest liquid the boy has ever seen. His father looks peaceful, something he has rarely seen, his eyes lazily drooping open and closed. When the day ends, his father remains, a lazy smile on his face and the drink drained.

He walks home along the docks again. It’s as hot as it was the first day he arrived, the sun distorting the brown water as it peeks over the horizon. He’s halfway home when he notices that he’s not alone.

Up ahead, there’s a team of haulers perched on the water’s edge. They look rough and weather worn. Some are smoking long pipes, others cramming large wads of bread into their mouths. A flat ferry boat bobs up and down beside them, tethered to the shore, the very same he had seen before. This time, there are large tubs of blue fluid strapped to the back, strung tightly with binding ropes and plastered with foreign looking labels. 6

As he approaches, one of the haulers looks up and flashes him a weary smile. “A landlubber!”

The boy stops, smiles, opens his mouth and then closes it again. A few of the other men glance round to where he is standing, their jaws grinding on bread and tobacco. “Are you the ferrymen?” he asks.

“We do any an’ all sorts,” says the man. “We’re waitin’ up. Special delivery. They’re closin’ up dock soon, so we can get out safe an’ all that.”

The boy glances over the boat’s cargo. There are stickers the whole way around showing symbols he’s never seen before. “What are you carrying?”

The man with the smile sniffs and picks up a bottle from beside him. “Med’cin. ‘Elps people stay still when they fidgetin’. Yer too young for that so don’t you be thinkin’ about it, ey?”

Some of the men turn back towards the water, he can hear their heavy breaths from a distance.

“I saw people on the boat. All bent and touching their toes. Are they divers?”

The man’s smile slips for a second. Everard’s son can see the lines on the man’s face thicken as he repairs it.

“They were jus’ getting’ from one place to another. Stretchin’. Retired folks. Stayin’ like that. It’s good for ’em.”

A few of the other men spare glances at the two of them, their eyes tired. The boy frowns.

“I get told off for slouching.”

The man’s smile fails. He raises his bottle towards the path out.

“The dock is closin’ up. I’d get yerself out. We got folks to put on board.”

On the seventh day, the boy arrives late to the yard. The air 7is scorching, burning the ground beneath the site. Despite it, the men are ploughing through. They are nearly at the top of the wall now, the sides forming a square.

He keeps moving, stamping down the dirt of the yard as he walks. The bones are cool to the touch today and they soothe like balm when he touches them. The boy starts with the corner-piece and climbs with it tucked snugly under his arm. He is growing to like the strange bones and their ridges.

As he reaches the top of the ladder, he glances over at the entranceway. There, planted in the dirt are his father’s boots. Only, when Everard’s son looks again, his father is bent in two. His hands graze the floor, tracing the sand as the wind sways him. The boy opens his mouth just as his father looks up, chin coated in blue, eyes glazed with a haze of white. His body, his calloused body is folded to a corner. Everard’s son looks down at the bone in his hand—

Heartbuzz

Saoirse Anton

A side step, wide step,

keep your distance stance

choreography of change

in our cautious daily dance.

It feels a step too far

from where we are at home

when no easy closeness keeps us

grounded through this storm.

But as the unknown swarms

a warm little buzz,

a pollen covered fuzz,

catches my ear and eye

and looking to my left I see,

nose in nectar nestled,

a bustling bumblebee.

No world-weary worry

weighs down these

busy wings,

as this bee buzzing sings a

song of honey-sweetness. 9

And with the sound of her song

I’m no longer in a

virus ridden, hunger bitten

news cycle circus world but

in this moment that unfurled

from the pollen heavy

petals of a flower.

In this bumble-industry

there is a stillness

as the storm spreads, relentless

outside the fleeting floral calm which

reassures.

One glance left

and I’m reminded,

that the world is turning,

deftly twirling in

the dance it always has.

Our choreography of change

will change again

to match new rhythm or refrain,

and when it does,

I’ll hear the echo of a little buzz

and know the heart beats on the same.

Silver Laces

Nisha Harichandran

Arms crossed, Kevin smirks, ‘There’s more than one, hon. Cut themall?’‘No,justthefront,please.’Kevin schedules a follow-up and waves me out. Puffing, my shoulders tense. I guess eloquence is not for all. But then, there wasn’t anything wrong with what he said. Kev was being direct. So, why and what am I choosing to hide? As thoughts percolate, the antique mirror catches my eye. Pausing, I check myself out and continue onto the main road, strutting like a peacock, flicking between smiles and frowns, whilst the freshly set curls kiss each cheek with equal affection.

Love a day at the salon. Best forty-five minutes and clears my head instantly. The few seconds of quiet evaporate at the sound of her voice. ‘Michele! It’s me, Jessica!’ Gliding the escalator like a swan on heels, she strides towards me, flaunting her ring finger. ‘Sealed it!’ She buries me in a hug. I give in awkwardly, for my hair’s sake. ‘Long time. How are you? Married?’ I shuffle towards the exit. ‘All good. Just back from a conference. Glad for the bank holiday weekend.’ Flapping her hands, she fusses, mocking my response. I squint, the diamonds dizzying my vision. ‘Alwaystalkingaboutwork.Clock’sticking,babe.Kisssome frogs. One’ll be a prince!’ Stroking my hair pitifully, she whispers, ‘They show. Can’t hide behind the highlights. Trust me, babe.’ I’d rather sky-jump than trust you babe, I wanted to scream but faked a smile instead. 11

My eyes drift to thoughts of college days, travels abroad, and then to the fluttering pages on my coffee table. Marked in bold, the quote reads, ‘Noteveryonehastheopportunitytogrowold.’ That’s bloody right. My silver laces are a privilege. Richard Gere oozes sexiness in his salt and pepper; I darn sure can rock mine. These laces witnessed my growth and supported my ambitions. I am keeping them.

Sauntering in, Kevin greets me, ‘Right on time hon. Cappuccino?’ ‘Yes, please.’ ‘The usual today? Root touch-up?’ ‘Yes’. ‘See a few whites, hon. Take them off?’ ‘Nope. Let them blend in.’

Mermaid Quay

Leusa Lloyd

I remember the days

When we lived in Cathays,

And we’d slip away to Mermaid Quay,

We’d drink down the docks –

JD on the rocks –

Singing songs of the plays we’d seen,

We’d walk to Penarth,

Hang our socks by the hearth,

Hot toddies until the flu passed.

We’d explore the Arcades,

That slink round like a maze,

As we soaked up the sun, we laughed.

Back at the Bay,

The Basin was black,

Clouds threatened attack,

And the currents were rough.

Back at the Bay,

You asked me to stay,

But I said this wasn’t enough. 13

Stricken with doubt,

At the jetty, I looked out,

On my tongue the taste of the sea,

Alone, at last, my tears flowed free,

My head a penitentiary,

Playing a fading memory:

Your kiss on my lip,

Your hand on my hip,

Your palm in my grip…

Oh, how the whole world would glitter for me,

When we danced round Mermaid Quay.

Sand and Foam

(WestWales,November 1956)

Sharif Gemie

Sometimes, at low tide, I find cockle-pickers, bent over in their waders, scrabbling in the wet sand. Sometimes, on sunny days, I see day-trippers arrive. They hold picnics on the grassy banks and their children build sandcastles and run along the shore, shrieking and laughing. But sometimes, like on this grey November afternoon, there’s no one. I walk over the glistening grey-blue sand and admire the ornamentation stretching out before me: reflections of clouds, sky and moments of sun. It’s as if I can walk to the horizon and beyond. Blake found infinity in a grain of sand, I glimpse it in this mad meeting of sand, sea and sky. I walk and walk, and I forget London and my wife and my work, I forget Eden and Nasser, I forget Suez and Hungary, I forget everything, just let it all dissolve in the swirling sea-breezes and the shimmering grey. My head empties, my limbs freeze, my lungs fill and something heals inside me.

But I can’t float away into this grey infinity. Two chains bind me to the earth: the time of the tide and the hour of sunset. As the blue of the sea turns a dimmer blue-grey, I turn round, trudge back across the glistening sand and I realise I’m no longer alone. There’s a white dot on the quayside. Each step brings me closer and new details emerge. A white square and a blue line – a canvas and a painter. What madman would paint this view today? A blue scarf, flapping in the wind. An 15arm raised, then falling. A cap. My God, it’s a woman. Not young, but – it’s hard to be sure, she’s wrapped up like a trooper in an old khaki greatcoat.

‘Afternoon!’ she calls out. ‘A study in grey, has to be, doesn’t it?’

She grins, white teeth flashing above her sky-blue scarf.

For a moment, I’m stunned. I’m frozen by the wind and I can’t think what to say.

She looks at her painting, dabs at it with her brush, hums a little.

‘Getting colder.’ She glances at me.

I have to speak. ‘You’ve – you’ve chosen an odd view. It’s all grey.’

I feel a stab of guilt. How can I betray my glimpse of infinity with these trite words? But I must keep it to myself, I can’t tell her, she mustn’t know.

‘I like a challenge.’

‘You’re from London?’ I ask.

‘Of course. Had to get away.’

I edge round to see her canvas and feel relieved that it’s just a seaside view, perhaps greyer than normal. She’s exaggerated the sunlight, decorated the sand with specks of gold.

‘Hmmm?’ she asks.

I nod.

She stands back, head to one side, assessing her own work.

‘Had to get away,’ she repeats. ‘Couldn’t face one more newspaper headline or wireless broadcast. Suez!’ She rolls her eyes. ‘Sometimes people are so stupid, aren’t they? Nobody doesanything, nobody knows what to do.’

I nod once more. What certainty! It’s refreshing.

‘Still…’ she sighs. ‘Politics, eh? I said I wanted to get away from it.’ 16

‘Everyone’s affected, I suppose.’ Somehow it sounds like I’m apologising. ‘It’s everywhere.’

‘Hah!’

She wipes her brush on a multi-coloured cloth, stares at her canvas.

‘It’s not finished,’ she says. ‘I’ll come back tomorrow.’

She packs up her paints and easel and slips them into one of those tartan shopping trolleys that housewives use for their weekly shop. The canvas perches on top.

‘Georgina.’ She holds out her hand. ‘Or Georgie, if you must.’

‘Edmund.’

We shake hands.

‘I’m here for the Creative Writing course. In town.’ She gestures along the bay.

‘You’re a student?’ I ask.

‘No, I’m the tutor.’

‘Really?’

‘Do you write?’

‘Not really, no.’

‘Still, come along if you like. Every evening, this week. Listen to the others. Beginners welcome.’ She smiles and steps towards me: she seems very close. ‘It starts tonight, seven o’clock, in the church hall.’

‘No, thank you, I won’t, I’ve got to…’

My voice dies away. There’s nothing I’ve got to do.

‘Suit yourself.’

She walks towards the town, pulling her trolley behind her. It rattles along the uneven quayside. She stops, looks back at me.

‘I’m staying over there.’ I point the other way, up the hill to my little cottage.

‘Right.’17